20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

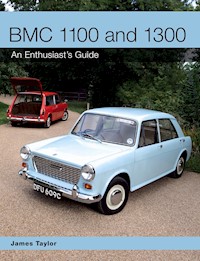

The British Motor Corporation's 1100 and 1300 model range was amongst the most successful in the Corporation's history, selling more than 2.1 million of all types between its introduction in 1962 and its demise in 1974. World-wide, it was sold under eight different marque names and in two-door saloon, four-door saloon, two-door estate, and five-door hatchback forms - and very nearly as a van as well. In Britain, it was the country's best-selling car between 1962 and 1971, being beaten just once (in 1967) by the Ford Cortina. BMC 1100 and 1300 looks at the design and development of a model range that at the time confirmed BMC as a pioneer of new automotive ideas and had a profound impact on other manufacturers. It covers not only the full standard model range, but special conversions, cars built abroad, and owning and running the cars today. Superbly illustrated with 150 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 244

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

BMC 1100 and 1300

An Enthusiast’s Guide

James Taylor

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© James Taylor 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 990 2

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1 ADO16: DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT AND OVERVIEW

CHAPTER 2 AUSTIN AND MORRIS: THE CORE MODELS, MK I, 1962–7

CHAPTER 3 AUSTIN AND MORRIS: THE CORE MODELS, MK II, 1967–71, AND MK III, 1971–4

CHAPTER 4 ESTATES: THE PRACTICAL MODELS

CHAPTER 5 MG AND RILEY: THE SPORTY MODELS

CHAPTER 6 WOLSELEY AND VANDEN PLAS: THE LUXURY MODELS

CHAPTER 7 BUILT ABROAD: THE OVERSEAS MODELS

CHAPTER 8 BUYING AND OWNING AN ADO16: THE RECKONING

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is sad that a car which was so central to the motoring scene in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s has been so largely forgotten. The BMC 1100s and 1300s were everywhere in those years, doing stalwart if unspectacular service as family transport, and there will be many people who still remember them fondly.

For anyone with a serious interest in these cars, membership of The 1100 Club is essential. Formed in 1985, the club provides advice and support on all areas of owning and enjoying these cars as classics today. A first port of call should be the website at www.the1100club.com. In 2012 the club also published a delightful scrapbook of 1100 and 1300 material, The Story of the BMC 1100, which is very much worth the attention of any enthusiast.

A lot of people contributed to the present book, many of them without knowing they were doing so. I suppose this list should begin with my school-friend Chris’s parents, who had a blue 1100 that he eventually ran into a ditch. They go on to include dozens of people in the old-car scene over a period of about forty years, and in particular I should single out a number of people who gave up their time at classic car shows to talk to me about their 1100s or 1300s, and willingly allowed me to photograph them as well.

Further photographs and material have come from my own collection, from the David Hodges Collection, from my friend Richard Bryant, from Glenn Smith in Australia, and from the archives of the Heritage Motor Centre. Special thanks also go to Magic Car Pics for photographic material, and to Barry Priestman of the Crayford Convertible Club for information and pictures from the club’s archives. To all those I have not had the space to name or the wit to remember, sincere apologies – and thank you, too.

© BMIHT – All publicity material and photographs originally produced for/by the British Leyland Motor Corporation, British Leyland Ltd and Rover Group including all its subsidiary companies is the copyright of the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust and is reproduced in this publication with their permission. Permission to use images does not imply the assignment of copyright, and anyone wishing to reuse this material should contact BMIHT for permission to do so.

James Taylor

Oxfordshire

December 2014

CHAPTER ONE

ADO16: DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT AND OVERVIEW

The BMC 1100 and 1300 model range was one of the most successful in the Corporation’s history, selling more than 2.1 million of all types between its introduction in 1962 and its demise in 1974. Worldwide, it was sold under eight different marque names and in two-door saloon, four-door saloon, two-door estate and five-door hatchback forms – and very nearly as a van as well. In Britain, it was the country’s best-selling car between 1962 and 1971, being beaten just once (in 1967) by the Ford Cortina.

Yet even though the 1100s and 1300s were technological pioneers in their time, they are rare at classic car gatherings today. One reason is certainly that they were built at a time when rust-proofing was almost non-existent on British cars, so that thousands upon thousands of these cars simply rotted away to a point where repairs were no longer viable. Another must be that they were deliberately designed as practical and unglamorous family cars, with no sporting pretensions (although the 1300GT can perhaps be considered an honourable exception), so that there was little to persuade enthusiasts to keep them alive. Finally, perhaps, familiarity bred contempt: there were simply so many of them that they tended to blend into the background.

In fact, the ADO16 range, as it was known to its manufacturers, was a significant engineering achievement of its time, and confirmed BMC as a pioneer of new automotive ideas that had a profound impact on other manufacturers. The saddest part of the ADO16 story is that when British Leyland inherited this excellent product, it was either unable or unwilling to build upon it, and instead created bland, unadventurous and frequently unreliable replacements that eventually made it the butt of every TV comedian’s jokes.

ORIGINS

To understand where the ADO16 models came from, we really have to trace the story back to 1952. That was the year when the two giants of the British motor industry, Austin and Morris, agreed to a merger under the umbrella title of the British Motor Corporation. This merger of rivals brought with it several subsidiary marques that had been acquired by the two organizations over the years – MG, Riley and Wolseley being the main car brands – and it also brought with it a number of problems. All of those marques had established strong dealer bodies, and those dealers had mostly established loyal customer bases. So there was considerable resistance below the surface to this attempt at unification: Riley dealers did not want to sell MGs, and Morris dealers did not want to sell Austins.

One aim of the BMC merger had been to make manufacturing savings by reducing the number of different models being built. There was no point, for example, in building completely different MG and Riley models when the two were actually competing for the same group of customers. So BMC responded to the problem with what is today often derisively described as ‘badge-engineering’. That meant creating one basic design but producing different variants of it with different badges to suit the different dealer chains. The ADO16 models were born into that period, and that was why there were so many different versions of what was really one car. In the UK, they carried no fewer than six different marque badges – Austin, MG, Morris, Riley, Vanden Plas and Wolseley – and outside the UK they carried a couple more as well.

For its first few years, BMC continued to build and sell most of the models it had inherited from the Austin and Morris groups. Some still had plenty of life left in them and in any case developing new models takes time. But by 1955, BMC’s Chairman, Leonard Lord (formerly the Austin Chairman), had embarked on a plan to rationalize the product range. He foresaw three basic models as the heart of the BMC car range, and they could wear whatever badges seemed appropriate at the time. There would be a large car, codenamed XC9001, a medium-sized car, XC9002, and a small car, XC9003.

Lord also wanted a talented engineer to lead the design teams, and his choice fell on Alec Issigonis. Issigonis had been responsible at Morris for the 1948 Morris Minor, a remarkable car that had completely outshone its Austin rivals, but he had sensed trouble when BMC was formed in 1952 and had left to work for Alvis. Here, Issigonis had designed an advanced new saloon car with an all-aluminium V8 engine, but sadly Alvis could not afford to put it into production. Lord recruited Issigonis for BMC and put him to work on the two larger car projects, XC9001 and XC9002.

It is the XC9002 that has most relevance to the ADO16 story, although it started life as a very different car. This was the medium-sized saloon, which at that stage had conventional rear-wheel drive and was intended as the eventual replacement for the Austin A40 and Morris Minor. However, work on the initial design was halted in early 1957 when Leonard Lord told Issigonis to abandon what he was doing and focus on the XC9003 small car.

What had happened was that petrol rationing had hit Britain in 1956, when some overseas governments had withdrawn supplies in protest against Britain’s invasion of the Suez Canal zone. The political events that led to that need no discussion here, but one result was that cars that used as little petrol as possible were in demand. A number of entrepreneurs capitalized on the fact by importing miniature cars from the European continent. Bubble-cars and the like became big business, and the major UK manufacturers had nothing with which they could compete. Lord intended that BMC should compete – and fast.

Alec Issigonis was the brilliant and innovative designer behind all BMC’s front-wheel drive cars of the 1960s: the Mini, the 1100 and the 1800. In the late 1940s he had also designed the much-loved Morris Minor.

Leonard Lord was not a man to be trifled with; what he wanted, he got, and the 1100 range was part of his mid-1950s plan for a unified range of advanced BMC cars.

The first of Issigonis’s designs for BMC was the Mini, which pioneered his space-saving packaging ideas when it was released in 1959.

Issigonis designed the new small car, which became the Mini on its 1959 announcement, around the need to obtain maximum interior space with minimum exterior dimensions. To that end, he designed a transverse powertrain, with the engine mounted across the front of the car and the gearbox mounted in the sump below it, driving the front wheels. It was a hugely effective solution, and so it was no surprise that he returned to it when he was allowed to start work again on the new medium-sized car, which was still known as XC9002.

His objective this time was to squeeze the interior dimensions of the latest BMC 1.5-litre saloons (the so-called Farina range) into the external dimensions of the Morris Minor, and the transverse powertrain packaging of the Mini enabled him to do this. Even with the wheels moved to the four corners of the car to give the long wheelbase that would give maximum ride comfort, XC9002 still had a wheelbase that was six inches shorter than that of the Farina saloons. With minimal front and rear overhangs, it ended up very much shorter overall than those cars, and at the time represented an absolute revolution in packaging.

This cutaway display model shows the side radiator arrangement, with air vents in the inner wing. To the right of it is one of the Hydrolastic suspension displacer units.

The overall layout of the ADO16 is shown in this cutaway drawing of a Wolseley 1100, with twin-carburettor engine.

Like the Mini, XC9002 was also going to have wheels that were much smaller than was then normal: in this case with a 12-inch diameter rather than the tiny 10-inch size used on the Mini. Issigonis made sure that there would be no compromises in ride comfort by engaging suspension specialist Alex Moulton as a consultant to BMC to work on the new car. Moulton had worked with Issigonis at Alvis and was a proponent of hydraulic suspension systems. It would be his Hydrolastic system that would be yet another innovation for BMC’s new medium-sized car when it was announced in 1962 – and the same system would go on to be used on the Mini three years later. With all these elements in the design, the first prototypes of XC9002 were constructed and began trials during 1958.

THE PININFARINA INVOLVEMENT

Leonard Lord, meanwhile, was not at all convinced that his existing designers – ‘stylists’, as they were called at the time – could come up with convincingly modern shapes for the cars he wanted. So in 1957 he turned to the Italian styling house of Pininfarina and requested a range of new designs that would cover all the planned new BMC models. The first to reach the showrooms was the Austin A40, with characteristically sharp Italian lines. Next came the medium-sized designs, the so-called Farina cars, which really introduced BMC’s badge engineering concept when they appeared with minor variations wearing the badges of the Austin, MG, Morris, Riley and Wolseley companies. The Mini, under development in this period, nevertheless escaped the attentions of Pininfarina, largely because of the rush to get it into production.

In the meantime, the early prototypes of XC9002 had been constructed with a simple and functional body design. This was distinctly dowdy and Lord decided that the car needed a more modern style to give it additional sales appeal. So later that year, Pininfarina was asked to work its magic on the car. Models were shipped across to Italy, and BMC stylist Dick Burzi visited the Pininfarina studios with body engineer Reg Job to explain what BMC wanted. By January 1959 a full-size model of the initial Pininfarina proposal had reached Longbridge. Interestingly, this was a four-door saloon, even though the early prototypes had only two doors.

Representing old-school engineering, but with modern Italianate styling by Pininfarina, this was the Austin A40.

Pininfarina also drew up the shape of the conventionally engineered Austin A55, which introduced BMC’s ‘badgeengineering’ to the world when it appeared with minor variations under a number of marque names. The cabin dimensions of this car were used as a target when Issigonis was drawing up the ADO16.

Len Lord felt that the new medium-sized car deserved top-quality styling, and bypassed his own styling team to give the job to Pininfarina. By January 1959 this is what the fashionable Italian styling house had designed.

Although this was on the right lines, its slab front and peaked headlamps were rejected as likely to create too much wind resistance, and the BMC body engineers felt that the shapes of the windscreen and rear window apertures would give trouble in production. So the Pininfarina design was reworked in-house at Cowley, and by July 1959 something very close to the production design had been achieved. The BMC engineers had widened the car by a few inches to allow for a full-width bench rear seat capable of seating three people, and introduced curved side glasses (then very new in the UK motor industry) as part of this widening process. Later, two-door and estate derivatives would be based on the four-door design, and both would be drawn up in the UK, although the final designs were also passed to Pininfarina as a matter of courtesy.

BMC’s production engineers and stylists then got to work on the Pininfarina design to make it more suitable for production and to improve its aerodynamics. By July 1959 this design was now in place, carrying the internal designation ADO16. The grille details would be changed before production began three years later.

PROTOTYPES

Now that the car was getting close to its production form, it was given a new designation. XC9002 had indicated that it was in the experimental stage; now it became ADO16. The Mini project had been ADO15 – the fifteenth design from the Amalgamated Drawing Office that had united the old Austin and Morris drawing offices – and the later large car, which had once been X9001 and would become the BMC 1800 at its launch in 1964, took the ADO17 name. Despite the dominance of Longbridge within BMC, quite a lot of the detail design work was actually done at the old Morris premises in Cowley, which would of course build a proportion of the cars once they were ready for production.

Once the basic design was in place, ADO16 was handed over to Charles Griffin (BMC’s Chief Engineer for Passenger Cars) to take forward to production. Griffin moved from Cowley to Long-bridge to do the job, becoming Issigonis’s deputy in the process. He also had far more to do with ADO16 than has generally been acknowledged. As he explained to Graham Robson in an interview for Mini Magazine, Issigonis was not really interested in the car; he was totally absorbed by work on the Mini. ‘He had the other models in his peripheral vision,’ said Griffin, ‘but no concentration on them at all. He was a genius though, no doubt.’ Meanwhile, serious work had also begun on the third model of that original trio of XC cars conceived under Len Lord. Issigonis divided his engineering teams into three ‘cells’: A-Cell focused on the Mini, B-Cell focused on ADO16, and C-Cell focused on the big car, the ADO17 that eventually became the 1800 ‘Land Crab’.

The first prototypes of what was recognizably the eventual production ADO16 took to the roads in 1960. Engineering development was based at the old Morris works in Cowley, near Oxford. A dozen cars were built for development work and were tested both on continental European roads and at the MIRA proving ground near Nuneaton in the Midlands. In those days, relatively little care was taken over secrecy and attendant disguise, and there was in any case far less public curiosity about unreleased car designs than has since become the case. So when the October 1960 issue of Motor Sport carried a ‘scoop’ photograph of an ADO16 prototype, the magazine was gentlemanly enough not to suggest it might be a Morris even though it was running on an Oxford trade plate! A French motoring magazine also caught a prototype on test and published a photograph.

A second batch of a dozen ‘improved’ prototypes was built and tested during 1961, and by the end of the year the car had been signed off for production. The first production examples, wearing Morris badges, were assembled at Cowley in January 1962, although the launch was planned for the Earls Court Motor Show that autumn to give production time to build up so that BMC would be able to meet the expected demand for their new car. This period was also used to refine the design and specification differences between the different models. Most of these would enter production later – Austins in 1963, Rileys and Wolseleys in 1965 – although the MG derivatives were launched alongside the Morris models in 1962. The Vanden Plas derivatives that were introduced in 1963 were nevertheless not envisaged at this stage, and nor were they designed by BMC, as Chapter 6 explains.

The car that entered production in 1962 as the Morris 1100.

BADGE ENGINEERING

The ADO16 was adapted to suit customers for no fewer than six of the old-established marques that had been brought together under the BMC umbrella in 1952. There would eventually be versions with Austin, MG, Morris, Riley, Wolseley and Vanden Plas badges, and outside the UK there would be versions of the car that carried Authi badges (in Spain) and Innocenti badges (in Italy).

Although MG, Riley and Wolseley employees could take no credit for the ADO16 design, it is very noticeable that Austin and Morris people both tended to promote ‘their’ marque’s contribution to the design. The old rivalries died hard.

The ADO16 range spread during the 1960s, although by the time of this 1971 picture showing the Mk III cars it had been somewhat reduced by British Leyland’s attempts at model rationalization.

THE RECKONING

As already noted, ADO16 rapidly became a best-seller in its home market, and it maintained that position for most of its production life. It was assembled not only in the UK but also in a number of overseas locations (seeChapter 7). There were locally manufactured versions abroad, too, as that same chapter explains. So in terms of its acceptance as a product, the car can only be judged as a huge success. At its peak in 1965–6 it was being assembled at a rate of just under 280,000 a year in Britain.

This success inevitably had its impact on the motoring scene in several different ways. For car buyers, the significance of ADO16 was that it changed expectations in the mid-size saloon market. It gave the family owner the benefits of modern technology – front-wheel drive and ruthless packaging efficiency – at an affordable price, and it showed how advanced technology could be employed unobtrusively for the benefit of the consumer. For its makers at BMC, it also advanced the company’s strategy – settled by Managing Director George Harriman in 1960 – of aiming for engineering excellence. (In practice, this was done because BMC did not have the resources to change models as frequently as its main rivals, Ford and Vauxhall.) Along with the Mini, it helped to alter worldwide perceptions of BMC, creating an image of a company that led with high technology to replace the old image of a stolid, conventional manufacturer that had been current in the 1950s.

It was George Harriman, by then BMC’s Managing Director, who settled on a policy of advanced engineering to help give BMC what would now be called a Unique Selling Point.

ADO16 also had a longer-term effect on the wider European motor industry. In Italy, for example, Fiat very quickly latched onto the idea of using front-wheel drive for space-saving. All the company’s small cars in the 1950s had used a rear-mounted engine with rear-wheel drive, but chief designer Dante Giacosa borrowed the BMC concept and modified it, putting the gearbox end-on and above the differential rather than in the sump, and using unequal-length drive shafts. Fiat were nevertheless unsure about the concept and decided to market the new car under their Autobianchi brand. The Autobianchi Primula was released in 1964, looking more than a little like the ADO16, and in 1965 the car came second in the European Car of the Year awards. In due course, it would be the Fiat engine and transmission layout, rather than the BMC type, that would become the standard for front-wheel-drive cars.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and the Autobianchi Primula of 1964 actually looked a lot like the ADO16 that had inspired it. Although its engine was mounted transversely and drove the front wheels, it used an end-on gearbox.

Replacements – sort of. The Morris Marina was a deliberately conventional car, aimed at people who had liked the Morris Minor 1000. The Austin Allegro did at least take forward some of the advanced engineering seen in ADO16, but was never much liked. The bigger-engined versions of both were intended to counter sales of the Ford Cortina.

Arguably, then, ADO16 was one of the cars that contributed to the British motor industry’s excellent reputation in the 1960s. However, behind the scenes there were undoubtedly problems. BMC was still struggling to get to grips with the large numbers of factories and dealership chains it had inherited, and the need to keep all those factories busy and to produce multiple different ‘badge-engineered’ versions of the same car made manufacturing costs higher than a more streamlined company like Ford was able to achieve.

These problems had not been ironed out before 1968, when BMC (which had become BMH, British Motor Holdings, in 1966) merged with the Leyland Motor Corporation to form the British Leyland Motor Corporation. That brought several more manufacturers into the corporate fold, with several more factories and several more rival model line-ups. British Leyland never really got to grips with all these – although the results of their early attempts were evident in changes to the ADO16 range in the late 1960s. Sadly, the task of unifying so many different companies was more than they could handle and one of the casualties was the forward-looking engineering that had gone into the BMC cars of the 1960s.

A further problem was that some aspects of the ADO16 design had not been thought through as fully as would be the case today. Alec Issigonis had perhaps been given too much control over the final product, and Graham Turner highlighted an example of this in his seminal book The Leyland Papers. Fleet sales accounted for about one-third of domestic car sales in the UK in the 1960s and, despite its widespread acceptance by private motorists, the ADO16 lost out to the Ford Cortina here for one simple reason: its boot was too small for travelling salesmen. As Turner says: ‘Alec Issigonis … might humorously describe a large boot as “a sales gimmick” but it was an essential ingredient of the “value for money” formula which the Ford Cortina was designed to embody.’ It is at least arguable that the problem was known and understood within British Leyland – after all, a ‘booted’ version of the car was developed on their watch to become the Austin Apache in overseas markets (seeChapter 7).

Despite its undoubted sales success, ADO16 never quite achieved its full potential. Its manufacturer’s profits were always minimal; for many years the multiple model variants made the range far more confused than it needed to be; and shortcomings of the design were not rectified as quickly as they should have been. In so many ways, the car stands as a metaphor for the whole of the British motor industry that collapsed after its finest hour in the 1960s.

WHERE WERE THEY BUILT?

The plan to build multiple different versions of the ADO16 to suit all the BMC marques implied production on a scale that the company had never before attempted. A complicated system was drawn up, using the Austin works at Long-bridge and the Morris works at Cowley as the final assembly plants for all UK-built variants. (There would of course also be assembly in some overseas plants, using Knocked Down kits supplied from the UK.)

These two plants played a game of Box and Cox in order to achieve the high volumes and the model mix required at any one time. Longbridge was a larger and more modern factory than Cowley, and not surprisingly assembled the lion’s share of all ADO16s. Most of its ADO16s were assembled in CAB2 (Car Assembly Building no 2), which was specially built for the purpose during 1962. However, all the estate variants were assembled alongside Minis in the older CAB1 plant, which also saw assembly of small numbers of saloons when demand was high.

Supplies of parts and sub-assemblies were fed into these two end-points not only from other factories within the BMC empire but also from major component suppliers such as Lucas, Smiths Industries and others. The body-in-white was pressed and built at five different locations. These were Austin at Longbridge (in the old West Works), Fisher & Ludlow at Castle Bromwich (who pressed panels for Riley and Wolseley models but also built all the estate bodies), Nuffield Metal Products in Birmingham (which built saloon bodies for Cowley), and Pressed Steel at Cowley and Swindon (which supplied both the Cowley and the Longbridge lines). All engines and gearboxes came from Longbridge.

The sheer scale of the ADO16 production operation demanded the involvement of a number of factories. These are 1100 Mk I body shells on the lines at the Pressed Steel works in Cowley.

Build locations for the different marques were as follows:

Austin

The Mk I saloons were mainly built at Longbridge, although some were also built at Cowley. All estates and all Mk II and Mk III models were built at Longbridge.

MG

All MG models were built at Cowley.

Morris

The vast majority of Morris models were built at Cowley, although there was some manufacture of saloons at Longbridge as well, and all Morris estates were Longbridge-built.

Riley

The Riley derivatives were initially built at Longbridge, but production transferred to Cowley during the Mk II era and remained there until the end in 1969.

Vanden Plas

Although BMC liked to give the impression that the Vanden Plas derivatives were hand-built at that company’s works in Kingsbury, in practice they were not: the Vanden Plas works was far too small to cope with such volumes. So the cars were initially built at Longbridge, subsequently transferring to Cowley from about 1968 with the other low-volume derivatives.

Wolseley

The Wolseley models entered production at Long-bridge in 1965, but then moved to Cowley, probably during 1968.

These complicated production arrangements were not cost-effective. As Graham Turner commented in The Leyland Papers,

Pressings for the 1100-1300 range came from Swindon and Llanelli and the body shells were then shipped from Swindon to both Cowley and Long-bridge for painting and trimming: the cost penalty for double assembly, according to the British Leyland planners, was at least £5 per model. Similarly there were wide cost variations between the four plants which produced bodies for the group: it was twice as expensive to make them at the plant at Castle Bromwich in Birmingham, where the Countryman models were assembled, as at Swindon.

THE A-SERIES ENGINE

All engines used in the ADO16 were variants of the BMC A-series, an overhead-valve design that had originally been drawn up as an 803cc type for the Austin A30, which was launched in 1951. Almost as soon as the BMC merger took place in 1952, the A-series was earmarked as the engine that would eventually replace the variety of small 4-cylinder types that BMC had inherited from its constituent marques.