0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

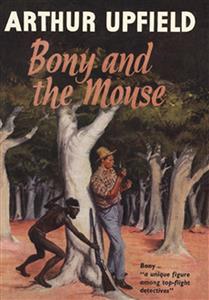

Three times a killer has struck at daybreak, a small town in Western Australia. What is the connection between these three very differently executed killings? Why is the local aborigine tribe always far away from the town at the time of the murders? Why should so many people suspect the strange 'bad boy', Tony Carr? This is a small community, seemingly too close-knit for Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte to penetrate...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Bony and the Mouse

by Arthur W. Upfield

First published in 1959

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Bony and the Mouse

Contents:

1

The Land of Melody Sam

1

2

Distorted Pictures

11

3

The New Yardman

21

4

The Magnifying-Glass

34

5

Introduction to Daybreak

44

6

Youth Without Armour

53

7

Digging for Nuggets

64

8

Melody Sam’s Private Eye

74

9

The Barman’s Morning

84

10

Sounds Within the Silence

94

11

George Who Wasn’t George

103

12

The Dreaded Event

113

13

A Stirring Day

124

14

An Opponent for Bony

134

15

A Feather Bed for Tony

144

16

No Foulness on our Hands

153

17

Bony Smells the Mouse

163

18

Trade in Blackmail

172

19

Material for Legends

182

20

The Daybreak Jury

192

21

Journey to the Hangman

202

22

The Fidget

213

23

The Cat

224

24

The Mouse

233

25

Repletion

245

CHAPTER 1

The Land of Melody Sam

Should you alight from the Q.A.N.T.A.S. air liner at the Golden Mile in Western Australia, travel northward to Laverton, then along a faint bush track for one hundred and fifty miles, you would come to the Land of Melody Sam.

Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte, equipped with a sound alias, did not travel by this route, as he had reason to enter Sam Loader’s kingdom by the back door. It was a clear, hot and windy day when first he sighted the Land of Melody Sam from the verge of a breakaway, and there he dismounted from a horse and rolled a cigarette whilst contemplating the scene. The breakaway was the granite lip of a vast and shallow saucer, on which grew a mulga forest the like of which is exceedingly rare in modern Australia, where steel axes have been frantically wielded for more than a century. The limits of the forest in the saucer could be seen; the entire area difficult to guess. Outside the saucer, on higher ground, there grew only the sparse jam tree, the waitabit bush, and the spinifex, patched by large areas of surface rock, and larger areas of salmon-pink sand.

Over beyond the many square miles of this mulga forest, Bulow’s Range lay sprawled above the eastern horizon, a pale-grey daub under the light-blue shimmering sky. Bony could see the burnt match-stick of the poppet head of Sam’s Find, and the outline of the town of Daybreak surmounting the whale-back Range, distant at least ten miles. There was the Land of Melody Sam, the destination of this traveller whose business was luring murderers from their holes.

The hot north wind ruffled the mane of the brown mare, and that of the pack-horse burdened with saddle bags, spare saddle, and the gear of a horse-breaker. Scorched clouds moved across the sky, and not one passed over the face of the conquering sun. From this breakaway were no limits to confine the soaring spirit of a man.

Down in the mulga forest it was different.

Again astride his horse, the man who was ‘Bony’ to all his friends rode through the forest which had aroused his interest in the story of its being. Before Cook first sighted Australia, an aborigine had stood on the breakaway and had seen, not this forest, but a vast flat expanse of spinifex dotted with jam-woods, gimlet trees, and ancient drought-stricken mulga trees of the broad leaf variety. Game was scarce, and he and his family were hungry, so he called the lubra whose job it was to carry the fire-stick from camp to camp, and with this he put the fire to the spinifex, for the purpose of driving into the open snakes, lizards, iguanas and banded ant-eaters.

Doubtless the present day was like that day, and the wind took charge and carried the fire across the saucer from side to side, burning everything to a grey ash. For many years the native trees had dropped their seed encased within iron-hard pods which nothing but fire-heat could burst open. They exploded like small-arms after the major fire had passed by, scattering the seed wide to fall into the cooling ash.

Quite soon thereafter came a deluge of rain and the seeds split open and sent their roots down into the steamy earth. A riot of spinifex and scrub covered the fire-bared land, and the mulga seedlings, proving the strongest of all, eventually gained the victory. More rain fell and, like Jack’s beanstalk, the saplings branched and the weaker of these were eliminated, the strongest ultimately surviving to claim their own living space, and leaving no surface moisture for anything else to mature.

Of uniform height, about twenty-five feet, they were uniformly shaped, the branch-spread dome-like, the trunks straight and metal-hard, and matching the dark-green foliage massed to give shade, unusual in the interior of this continent.

Bony and his horses passed over the parquet floor of salmon-pink and shadow-black. The wind hissed and raved among the topmost branches, and failed to sink low enough to reach him. The summit of the arches swayed; the walls of the arches did not move.

Nothing else moved either. There being no ground feed, there were no animals to be seen; and no reptilian life, and thus no birds. The entire absence of lesser trees, low scrub and spinifex, and grass, quickly made of it an empty forest. It was almost a relief to enter the clearing, and Bony dismounted at the edge of it and rolled a cigarette, whilst the horses nickered and raised their upper lips to the scent of water.

Bony found the water in a deep hole among a rock-pile, and beside it a bucket fashioned from a petrol tin. Thus able to give the animals a drink, he loosened saddle girths and boiled water in his quart pot and brewed tea. Seated in the shadow of the rock-pile, he lunched leisurely and ruminated on his mission.

The Case-files, the Statements, the Plaster Casts of shoeprints, and the Reports of Detective-Officers, seemingly piled as high as this isolated rock-mass, had given him a fairly clear picture of a community, and the shadow of murder which had fallen upon it. Daybreak, a town which had been created by one man, and seemingly controlled by this man, of unknown age and known to every prospector and miner in Western Australia as ‘Melody Sam’. Three hundred miles from Kalgoorlie, a hundred and fifty miles inward from the end of the terminus of a branch line at Laverton, all this country unfenced, unused, never properly prospected, save a ribbon either side of the unmade road based on the rail-head. And they called it ‘The Land of Melody Sam’.

Daybreak, a one-pub town owned by Melody Sam. He owned the general store, he financed the mail-and-goods run from Laverton. He built and owned the church and paid the parson’s stipend. He built the court-house, the school of arts, and would have built the police station, the post office and the school, had the authorities agreed. He did not, therefore, pay the salaries of the officials.

Melody Sam. A tycoon! A dictator! A political boss! There was only the one verdict provided by the records. Melody Sam was universally honoured, if not universally loved. It seemed that he had one failing in the estimation of his people: he would, without notice, march up and down Main Street playing a violin very well, but not the tunes in greatest favour. And, too, he was a trifle unpredictable. No one could forecast the hour when he would start on a bender which might last many days.

Murders at Daybreak! There were three, the first that of a young aborigine called Mary, who was a protégé of the minister and his wife. In July of the previous year she was found on the footpath outside the Manse, having been killed with a blunt instrument. A month later a Mrs. Mavis Lorelli, the wife of a cattleman living five miles on the road to Laverton, was found by her husband, having been strangled during his absence. In January of this year the third murder had been committed, this time the victim being a youth employed in the town as garage apprentice. His throat was cut.

Now it was April, ten months after the aborigine’s death, and nothing achieved by the police, other than a collection of plaster casts of sandshoes worn by a man having a slight limp in his right leg.

It was surprising how many men living at Daybreak had an injury to their right leg, and yet not so in a comparable community of bush people. It was strange that the local aboriginal tribe was absent when the girl was killed outside the Manse, for the aborigines were on walkabout and she should have been with them. It was also odd that when the remaining two crimes of homicide were committed the tribe was away on walkabout, and the policeman had to call for the services of a native tracker at Kalgoorlie, and he seemed to be useless.

It was reasonable to assume that one man killed these three people. His tracks were found on the scene of the second and third murders, and the plaster casts made of them identified him on each occasion. There was nothing more of any value. Motive was not indicated. No one crime was related to the others.

Suspects? Only one, a young man named Tony Carr, a teenage delinquent of bad record, and now employed by the local butcher.

Quite an unusual set-up, and not to be resisted by D.I. Bonaparte when in Perth on an assignment. On the evening before leaving Perth he had dined with the Commissioner and his wife, and the Commissioner had wished him luck, and the Commissioner’s wife had urged him to make himself known to her niece, Sister Jenks, from whom he could obtain much local colour.

Sister Jenks! She had often appeared in the case records. Constable George Harmon, it would seem, was efficient and inclined to be ruthless. There was a man called the Council Staff, and Katherine Loader, Melody’s granddaughter. A man named Fred Joyce did the butchering for Daybreak, and was stated to be guardian-employer and general tamer of the delinquent Tony Carr. And, of course, others, including a gentleman called Iriti, and his medicine-man, having the euphonious name of Nittajuri.

Too small a town, a too closely related community for a detective-inspector to enter in full uniform of braided cap and sword and spurs. Success would surely attend on an itinerant horse-breaker called Nat.

Bony tightened girth straps, and left the rock-pile, to be immediately intrigued by an arrangement of stones, obviously the work of aborigines. The stones were roughly circular and flat, each about the size of a white man’s soup plate. Between each was a space of about two feet. They formed two circles joined by a narrow passage, that farther from the rock-pile being much larger than the nearer one. Twenty men could have stood without contacting one another in the larger circle, ten could have done this in the smaller one, and two men could walk abreast along the connecting passage, a hundred yards long. At the far curve of the large circle, three stones were missing, so that it was possible for a man to walk into the circle, and from it along the passage to the small circle, without stepping over the outline of the design.

An aboriginal ceremonial ground. The carefully selected stones had been brought from outside the forest. All were of white quartz. The upthrust of rock, amid which was water, was, however, of conglomerate ore, and thus evoked the question: why bring stones from outside the forest when a plentiful supply was to be obtained on the site?

There were additional points. The white stones were maintained in regular spacing, and free from drift sand. The absence of human tracks proved that the design had not been used for a ceremony for some time. It was a secret place which no white man would have reason to visit in a search for lost cattle, or on a kangaroo hunt. It was a lonely place, a magic place, and Bony was sure that amid the rock-pile was the local tribe’s treasure-house where were kept the pointing-bones and the father and mother churinga stones.

The spirits of his maternal ancestors came from the trees to whisper their taboos. Under the wind there was a silence, a watchfulness by the unseen, and sudden withdrawal from this place, of the world of living men. Bonaparte’s white progenitors mocked him in these moments, called up his education, his reputation, to wave like flags before his eyes.

He compromised by leading his horses round the edge of the clearing to avoid crossing over the ceremonial ground, and so continued his journey through the forest, which never varied in aspect from what it had been before coming to the rock-pile. The floor of salmon-pink sand, unmarred by the feet of man or beast, continued flat and unruffled by the defeated wind. Can a man disown his father and his mother? In the mind of this man, so constantly battled for by his unknown parents, the thought was created that in every one of these identical trees was imprisoned for eternity the spirit of a once living aborigine.

Bony must have ridden nine or ten miles since leaving the breakaway, when he sighted the eastern extremity of the forest, vistas of space appearing in the arches, and extending as he approached. Before him was no rock-faced breakaway. He could see the land rising gently beyond the mulgas, could see in the open spaces the snow-white trunks of several ghost gums.

The mulgas thinned at the forest limit, and the ground here was scarred by shallow water gutters. He found he hadn’t done badly when crossing the maze, for he was out of course for Daybreak by very little when he saw the town on the curved back of Bulow’s Range. A four-wire fence skirted the forest, obviously marking the boundary of the town common, and he rode to the right, hoping to come to a gate, and thus disturbed a party of crows settled on an object slightly inside the forest. Well, it was early yet, and curiosity took him to the crows’ find—the body of a doe kangaroo. And at once his attention was removed from it to the story written on this page of the Book of the Bush.

A barefooted woman accompanied by a dog had run into the forest. The dog had killed the kangaroo. The woman had fallen, and had lain on the ground for some time. Then she had crawled over the sandy soil out of the forest to the skirting wire fence. She was a white woman.

Bony urged his horses along the track of the crawling woman, coming to the fence, and seeing that she had crawled beneath the bottom wire, and so on into the open country, and towards the seven or eight widely spaced and ancient ghost gums. Tethered to one of the gums was a saddled horse. Bony cautiously followed the trail of the crawling woman until he came to the edge of the slight depression where grew the ghost gums.

Under one of them a woman was lying, and a man was bending over her with a long-bladed knife lying horizontally on his two hands, as though he were contemplating just where to plunge it.

CHAPTER 2

Distorted Pictures

The man was oblivious of Bony’s proximity. The woman lay with her eyes closed, and her light-gold hair was draggled, her face stained and white. She said:

“Go on, Tony Carr, cut it out. You got to cut it out.”

“I tell you I can’t. I couldn’t do it,” reacted the man.

The long knife was lifted from his hands, and he was aware that someone knelt beside him before moving his gaze from the woman’s foot, to encounter the blue eyes of a stranger. Swift in defence, he explained:

“She got a rotten splinter in her foot, and she wants me to cut it out. Look at it! It’s dug in inches. She’s been here since yesterday morning. She’s had it. I found her with her mouth stopped up tight with her tongue ‘cos of thirst.”

The stake was driven in just behind the toes, deep in the sole and almost to the heel. It was fifteen or sixteen inches long, iron-hard, a wind-break from a mulga.

“I want a drink, Tony Carr,” moaned the girl, for she was not yet twenty, and now her eyes were open, and golden, like her hair.

“Didn’t ought to have any more for a bit,” said the young man, looking appealingly at the stranger. “You mustn’t give ’em a lot when they’re like that.”

“You make a fire and I’ll fetch water and things we’ll want.”

Retaining the knife, an old butcher’s killing knife honed to razor-sharpness, Bony brought a water-drum, billy-can and quart pot, tea and sugar, and a simple first-aid kit.

“I came this way to push cattle up to the yards,” Carr explained, as Bony made his preparations. “I see her dog on a rock. The dog is famished, and then I see Joy Elder lying here. She says she was looking for garnets. Her and the dog put up a kanga with a fair-sized joey, and the dog chased the kanga over the fence into the mulga, and she went in after and landed her foot on a stick lying buried with the point just sticking up like.

“She knows that no one ever goes in there, so she crawled out under the fence and got this far. Couldn’t pull the stick out, and couldn’t walk with it in. A mug could see she couldn’t. That was early yesterd’y morning. When I got here she can’t talk. Tongue swollen that big. So I dripped water from me bag on her tongue till it sort of loosened up, like the blacks say you gotta do. You can’t let ’em have a lot of water straight off. Look, mister, I’m slaughterman at the butcher’s, but I can’t take that stick out. What are we gonna do?”

He was solid, this Tony Carr; thick and wide and not so tall. His bare forearms were sunburned to match the backs of the powerful wrists and hands. His features were rugged, his eyes brown like his hair, and at this moment his face did not support the dossier Bony had studied when in Perth.

“We have everything ready,” Bony said. “When I tell you to grip the ankle firmly, you must do that.”

Going to the girl, he placed a wet rag over her eyes, saying gently:

“It will hurt, but you must bear it. Think you can?”

“Yes. Oh, yes. Please get it out.”

Tony Carr didn’t watch this bush operation. Gripping the ankle as instructed, he felt her body rebel against the knife, heard her sharp cry, and himself felt the pain, and then felt the patient’s relief when her taut nerves relaxed, and she gave a long sigh. On being asked to release the ankle, he saw that the gentle stranger was packing the wound with gauze.

“My guess is that the town is something like four to five miles away. There’s a nursing sister there?”

“Yes, Sister Jenks. But Joy here lives at Dryblowers Flat. We goin’ to carry her?”

“Better not try that,” decided Bony, glancing swiftly at the semi-masked face of the girl. “You ride hard for the town and tell them to bring a truck and a stretcher. Tell Sister Jenks just what has happened. Now get going.”

The boy left at a gallop over the rough ground. The dog came and nuzzled the water-bag, and Bony punched a dent into the crown of his hat and filled it for the famished animal. Testing the tea poured into the tin cup, and finding it cool enough, he added a little sugar, and knelt beside the girl and removed the now dry rag. Her large golden eyes were swimming in tears of exhaustion.

“This is going to be good,” Bony told her, slipping an arm under her shoulders. “ ‘Joy’, the young man said. ‘Joy Elder’ and you live at Dryblowers Flat. Now don’t gulp so. There’s plenty more, but we must take it slowly.”

When refilling the cup he heard her sobbing.

“I can’t help crying. I can’t . . .”

“Of course you must cry,” he told her. “Here’s a clean handkerchief. Cry all you want. Do you good. Now a little more tea, and then rest for a while. Your dog was famished too. Must have stayed with you all along.”

The girl nodded, and managed to call, and the dog came and crouched beside her. “He bailed up a kanga in the mulga, and when I got to him, the mother was fighting him off and she had a baby in her pouch. It was when I ran to haul him off the kanga that I got the stick in my foot, and I couldn’t do a thing about the kanga after that. So I crawled out to here, hoping Tony or Mr. Joyce might come this way looking for cattle.”

“And you go out looking for garnets without wearing shoes?”

“Us girls don’t wear shoes exceptin’ when we go to church in Daybreak,” Joy explained, tiredly, and Bony thought that to talk was better than not. “Janet and I live with father, who’s a dryblower. Father’s pretty old, you see, and we haven’t much money. And besides, why wear out shoes? Father says we ought to, though. Then father says me and Janet are both as wild as brumbies, and we ought to be our age. I suppose we are wild and all that, but we can take care of ourselves. Pompy, you see, knows judo. All the kids have learned it off him.”

Wearily she said she was just over eighteen, and then fell asleep with his arm still about her shoulders. The ants were bad, and the flies too. He brought the blanket roll from the pack-horse, and laid a blanket on hard clay-pan in the shadow and moved her to it. Then he sponged her face and sat beside her to prevent the flies from settling. He doubted she would have lived through the coming night. He wondered why no one had looked for her.

An hour later he was still keeping the flies at bay when three horsemen rode over the low ridge and down into the depression. Tony Carr was one of them. Another was large and hard, gimlet-eyed and stiff in the saddle. The third man was also large but not hard, and his eyes were frank. He rode loosely and with the ease of one used to horses all his life. They alighted, and the gimlet-eyed man advanced to stoop over the girl, listen to her breathing and lift the groundsheet to inspect her wounded foot. Straightening, his eyes widened. They were hazel and penetrating.

“Now, what’s your name, and where d’you come from?” he demanded.

“Who are you?” returned Bony.

“Police,” snapped the big man.

“The name is Nat Bonnar. I’ve come down from Hall’s Creek. I’m looking for horse-work. I was on my way to Daybreak when I came across this young feller trying to make up his mind to cut the splinter from the girl’s foot. We did that, and he went off to Daybreak for help.”

“What time did you get here?”

“Between four and five, I suppose.”

“You ought to get nearer than that. Your kind can generally tell the time by the sun. What was this young chap actually doing when you first saw him?”

“As I said, making his mind up about cutting a stick from the girl’s foot.”

“When you got here, was she unconscious or asleep?”

“She was conscious. I heard her urging the young feller to cut the stick out.”

“And between you, you cut it out. Why didn’t you pack the girl on one of the horses and bring her up to town?”

“ ‘Cos she was all in,” Carr replied for Bony, and was roughly told to shut up.

Tony’s hands were clenched, but the policeman continued to stare at Bony, waiting for him to answer the question.

“The girl was exhausted by pain and exposure and thirst,” Bony said evenly, and continued: “Also the golden rule is not to move an accident case until first examined by a medical expert.”

“Ah! Know-all, eh! When you first came in sight of this business, what was this young feller really doing?”

“He was kneeling beside the girl. He was looking at the stick protruding from the injured foot. In his right hand was a long, pointed knife. As it was obvious he wasn’t going to cut the girl’s throat, I tethered my horses, and knelt beside him. He said, in reply to the girl’s urging: ‘I can’t’, and I said: ‘I can’. We then proceeded to remove the stick.”

“You sure he wasn’t interfering with her?”

“Interfering with her!” echoed Bony, his eyes masked. And the big man snapped:

“That’s what I said. Come on. Out with it.”

“Nice clean mind you have,” Bony said and, indicating Tony, added: “Looks all right to me. No black eyes. No bones broken.”

“Huh! We’ll see what the girl says when she comes to. So you came from Hall’s Creek, eh! What were you doing up there?”

“Breaking in a couple of colts for the policeman.”

“So. And the policeman’s name?”

“Kennedy. Constable First-Class.”

“Oh! Soon check. I gotta horse you can break for me.”

He turned back to the girl, and Bony and Tony turned with him. The other man was bending over the girl, peering into her face, and on the girl’s other side the dog was crouched with belly just clear of the ground, and lips lifted to reveal white fangs. The dog went to ground when the man straightened and said to the policeman:

“Sleeping all right. Musta had all it took. Lucky these two happened along.”

“Yes,” agreed the policeman. “Coincidence. I don’t like coincidences. No one comes down here ever, except you, Tony Carr, and you must explain just why you came this way this afternoon. And you too, whatever’s your name. Blast! The stretcher party should be here by now.”

He strode away from them, proceeding to circle the place and examine the tracks left by horses and men, and must have seen the trail left by Joy Elder when crawling to the tree. It was then that the stretcher party appeared on the ridge, and he returned to meet them.

There were several men, two of them carrying the folded stretcher, and a young woman wearing blue slacks and a red jacket. As she came down to the floor of the depression, her walk bespoke the agility of youth. Bony estimated her age as well under thirty. Her hair was reddish-brown, and it glistened beneath the brim of the shallow straw hat.

Her interest was limited to the injured girl. They stood back watching her, noting that she felt the girl’s pulse, then regarded the bandage about the wounded foot, without touching it. She spoke to the girl and, receiving no answer, raised an eyelid.

“All right, Bert Ellis, bring the stretcher. The blankets first, please, and one to cover her. Better take her to town. She’ll need a little watching. You’ll supervise, Mr. Harmon?”

“Righto, Sister,” agreed the policeman.

Sister Jenks stood, nonchalantly produced a cigarette-case, and removed a cigarette. A match was struck, and above the flame she looked into the masked blue eyes of Napoleon Bonaparte. She glanced away to the men engaged with the stretcher, protested at their work, and herself arranged the lifting of the inert girl to the stretcher and directed the manner of the covering. Bony was taking the now unwanted blanket roll to the pack-horse when he heard her call him. She wanted to know who he was. He told her.

“You removed the stick, I’m told.”

“Yes, Marm,” he replied, looking into her dark eyes, surveying the delicate features of the small face, not the least revealing being the determined chin.

“What did you do?”

He detailed the rough operation with the sterilised knife, the antiseptic and subsequent dressing.

“Sensible,” she voted. “You couldn’t have done better in the circumstances.”

“Thank you, Marm.”

“Oh, that’s all right . . . Bonnar, I think you said? Don’t call me Marm. I’m Sister Jenks, and I’ve never been married. May I be inquisitive for half a minute?”

“For ten minutes do you wish, Sister.”

“All right. See if you’ll smile at my questions. Your mother was an aborigine?”

“I have been so informed,” Bony replied, smiling slightly.

“And your father was white?”

“That is additional information, Sister.”

“You are an oddity, Bonnar—a man of two races having adorable blue eyes. Are you not Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte?”

“Could be.”

“End of inquisitiveness, plus rudeness. No forgiveness asked. I am very glad you have come. We are not at all happy in Daybreak. You are working incognito?”

Bony nodded, saying:

“In this investigation a horse-breaker might succeed more quickly than a known detective.”

For the first time, Sister Jenks smiled, and Bony was obliged to keep pace with her.

“I hope to meet you again soon,” she said. “I must tell you what my aunt says about you, just to see how vain you’ll become. Now I must hurry after my patient. It’s going to be fun knowing you. And I shall keep your secret.”