0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

At first it seems obvious that Old Fren Yorky had murdered Mrs. Bell; several of his footprints are identified near the body and is known to have been nearby at the time of the crime. But to find him is a difficult problem. He has disappeared completely, taking Mrs. Bell's ten-year-old daughter Linda with him, leaving no trace. Even the aboriginal trackers are baffled. The dijeridoo, a magical instrument played by blind Canute, the headman of the aboriginal tribe, at a secret corroboree, gives Bony his first clue. But before he can try to trap the murderer into giving himself away, however, Bony has to buy the beautiful Meena from the aboriginals and risk her life and his on the treacherous mud of Lake Eyre.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

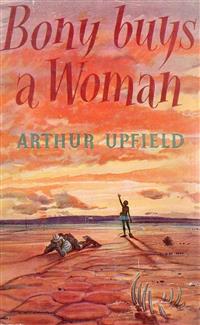

Bony Buys a Woman

by Arthur W. Upfield

First published in 1957

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

by

Contents:

1

A BEGINNING FOR LINDA

2

MURDER IN EDEN

3

THE DECEITFUL LAND

4

MOUNT EDEN WELCOMES BONY

5

DIGGING

6

THE ART OF REASONING!

7

SAVAGES AND BYRON

8

MUCH ADO ABOUT A BLOODSTAIN

9

TO RUN IS TO CRAWL

10

IN EFFORT TO TRADE

11

BONY’S GUESTS

12

PRODDING THE ENEMY

13

BALANCING RESULTS

14

THE FUGITIVE’S STORY

15

BOARDS AND DINGO ROADS

16

BONY BUYS A WOMAN

17

BONY TRADES HIS WOMAN

18

DECISION TO DYNAMITE

19

EXTRACTING INFORMATION

20

THE WAGES OF BLUFF

21

THE SINK OF AUSTRALIA

22

THE CORPSE OF THE PAST

23

A MIXED RECEPTION

24

THE QUAIL SHOOTERS

25

PINNED LIKE A SPECIMEN

26

BREACHING A WALL

27

A PRESENT FOR CHARLIE

CHAPTER 1

A Beginning for Linda

The day was the 7th of February, and it was just another day to Linda Bell. Of course, the sun was blazing hot at six in the morning, another morning when the wind sprang up long before six and was a half-gale when the sun rose. It sang when crossing the sandy ground, and roared farewell as it sped through the line of pine trees guarding the Mount Eden homestead from the sprawling giant called Lake Eyre.

For Linda this day began like all other days. First she slipped from bed and gazed at the large calendar on the wall above the dressing-table. Later she would be asked to name the day, and already she knew that to remember it would be conducive to happiness.

Linda was most self-dependent although she was only seven years old. She needed no rousing, no instructions on how to begin a new day. Taking a towel from a rack, she tripped daintily through the open french windows to the veranda, and along the covered way to the shower recesses. She sang a little song to the accompaniment of the wind under the iron roof as the tepid water from the great tanks high above the ground sluiced down her white body. Now and then into the song crept the word ‘seven’, and the same word occurred when she was still singing, on regaining her room and proceeding to dress. She was making her bed when the breakfast gong without defied the wind, to call the Boss and the Hands.

The homestead kitchen was large, already hot, filled with the aroma of coffee, frying mince-balls and grilling steaks. At one end stood the small table where Linda and her mother ate, and at the other end was the annexe in which the men ate. The men appeared and sat at the long table, and Mrs. Bell asked each what they chose, and served them. That done, she served a cereal to Linda without consulting her, and then carried Mr. Wootton’s breakfast tray to the inner dining-room.

Mrs. Bell was plump, fair, thirty, and pleasing to behold. It was said that her husband was a horse trainer, and that she had once been a school teacher. She believed that children were no different from horses—that they needed to be trained with firmness and kindness, and that if training is left too late, the child becomes a useless adult, precisely as belated training is wasted effort on a horse or a working dog. Thus she spared herself no trouble, but saved herself much worry.

“You have done your hair nicely this morning, Linda,” she observed as she sat at table with her daughter. “Saves time to do it nicely in the first place. What is the date to-day?”

“February Seven, One Nine Five Seven,” intoned Linda, her grey eyes wide and faintly impish.

“That’s my girl,” approved Mrs. Bell. “Mr. Wootton says he’s going to town to-day, and I see that your comb has lost two teeth. What colour would you like the new one to be?”

Linda chose blue, but her mind was on the slight noises made by the hands leaving the meal annexe. Her mother asked her to tell the time by the wall clock.

Hurrying now to finish her breakfast, Linda’s jaws slowed while she gazed at the clock. Then she guessed a little, as she always found it difficult to be sure whether before or after the hour. This morning she guessed correctly by answering:

“Seven minutes to seven, mother.”

“Good for you, Linda. Now I suppose you want to run out to see the men off to work. Well, you may go. When the men have left, come in and do your lessons. It’s going to be a nasty day, and we’ll get through as quickly as you’ve a mind to, shall we?”

The homestead buildings at Mount Eden formed the sides of a large square. The main house occupied the east side, the men’s quarters the side opposite. On the flanks were the office and store shed, the horse yards, the trade shops, the well and reservoir tanks. In the corner of the square was a round house, constructed entirely of canegrass.

When, a trifle too hurriedly, Linda said grace and skipped from the kitchen, she stepped right into the open square. Already the early morning shadows were deepening in sharp contrast with the sunlit ground, and squadrons of dust horses ridden by riders of the west wind were racing from the men’s quarters to the house, passing by and speeding up the slope to the line of pine trees and the vast open Lake Eyre beyond them.

The men were coming from the quarters to receive their orders for the day. There were four, all white men. Three wore spurs to their riding boots. One was a heavy man, two were lean, and the fourth a young man darkly handsome, and, compared with the others, almost flashily dressed in the ultra-stockman style.

They halted just outside the office door. The young man waved to Linda, and the big man called the morning greeting. Then Mr. Wootton appeared from the house side veranda. He was short and stout, red of face, when the complexion of his men was uniformly nigger-brown. His clipped moustache was dark. His hair was worn short and was plainly grey at the temples. His eyes were small and distinctly green, and always kindly for Linda. To her he was the Big Boss, the King of Mount Eden. Unfailingly he must be called ‘Mister Wootton’. Invariably he wore a soft-collared shirt and a tie, gabardine trousers and shoes, instead of riding boots.

As usual, Mr. Wootton slipped a key into the office door lock and entered. He was invisible for two to three minutes and Linda knew he was studying a big book kept on his desk, and knew, too, that he looked into the book to tell him all about the station, and what needed to be done. On reappearing, he stood in the doorway and called for Arnold.

Arnold was the very large man who could do anything from blacksmithing to making a motor engine go. Because of the wind and the cawing of passing crows, Mr. Wootton had to speak loudly.

“Want anything from town to-day, Arnold?” The big man shook his head, saying:

“Don’t think so, Mr. Wootton. Not for the station, anyway.”

“All right. The wind oughtn’t to be strong out at Boulka. You might take the truck and go for another load of iron. And take your time to get the iron off without tearing holes in it. You know.”

“Good enough,” drawled Arnold, and Linda asked:

“May I go with Arnold, Mr. Wootton?”

“If your mother says so,” he assented, and called Eric.

Linda raced to the house. Eric was lanky, raw-boned, slow. When Linda returned he was saying:

“The mud’ll keep ’em from crossing for another six weeks even if it don’t rain, which ain’t likely. Them steers know enough to shy off getting themselves bogged. ’Sides, before the lake is hard enough to take ’em, the flood oughta be right down the Coopers and the Georgina, an’ spilling over from the Diamantina.”

“Could be, Eric,” agreed Mr. Wootton. “Well, take a ride out to Number Fourteen and look over the stores. Anything you want from town to-day?”

Eric chuckled dryly, and winked at Linda.

“Well,” he drawled, “you might bring me a box of them lollies with the nuts on ’em. Seems like I got to give a present to my girl. Must keep in with her, y’know.”

“Yes, you must get a present for your sweetheart,” agreed Mr. Wootton, seriously. “Is her name Linda, by any chance?”

“That’s tellin’, Mr. Wootton,” and again the wink which produced beaming adoration in the little girl’s face.

The next man called to receive orders was the young man named Harry. He came forward with rolling gait, and even the wind could not drown the tinkle of his spurs. He was sent out to ride a section of the boundary fence. The fourth man, named Bill, was instructed to ride into White-Gum Depression and report on the feed. To him Mr. Wootton put questions concerning the aborigines.

“Any sign of Canute and his people, Bill?”

“Sort of local? Naw, Mr. Wootton. They’re never to hand when wanted. They’ll be away up on the Neales by now, living on lizards and ants, going for corroborees and such like, and putting the young fellers through the hoop.”

“Charlie promised he would come back early to give a hand with the muster.”

“You’ll see Charlie when you see Meena. And that’ll be when Canute says so. He’s their boss. You can send ’em to the Mission Station, teach ’em to read and write and sing hymns, but in the end they do just what old Canute tells ’em.”

“Yes, yes, I know,” Mr. Wootton agreed explosively. “All right, Bill. Want anything from town?”

“Well, you could bring me a coupla pairs of them grey pants you got me last winter. Oh, an’ what about a couple of ladies’ handkerchiefs? Small ones with lace round the edges, and the letter ‘L’ in the corner. The store’ll have them kind. I got a sort of sister called . . . why, hullo, Linda, I didn’t see you.”

“You did so, Bill,” argued Linda, from whose face disappointment had been banished by joy.

“Oh, Linda!” said Mr. Wootton. “Will your mother allow you to go with Arnold?”

“Mother says not to, Mr. Wootton. Mother says I have to stay and help her because Meena and the others are still away.”

“I didn’t think of that, Linda. Of course you must help your mother. All right, Bill, I’ll not forget the handkerchiefs and the box of nut chocolates.”

Mr. Wootton re-entered his office, and Linda accompanied Bill to the yards, where the other riders were saddling up. She watched them leave, and then went back to the house, and demurely dried breakfast dishes for her mother.

After that, lessons at the kitchen table until nine o’clock, when Mrs. Bell sounded the house gong, made tea and provided buttered scones. Mr. Wootton came to the kitchen for morning tea, standing the while, and noting on a pad the items Mrs. Bell needed. Linda accompanied him to the car shed, and stood watching as the dust and sun-glare took the car up into the sky over the track to Loaders Springs.

She was now free for the remainder of the morning, free to be herself, free to chide and scold and love, instead of being chided and loved. There beside the car shed was her own house, a circular house having canegrass walls and a canegrass thatched roof, and a wood floor three feet above ground to keep the snakes and the ants out; a little house for a little girl, built by the girl’s sweethearts.

Thus far, just another day for Linda Bell.

She ran up the two steps and through the thick grass doorway to enter her house, leaving the buffeting wind outside, and meeting with calm silence. There was a real window set in the thick grass wall, and the window faced to the south, from which the cool winds of winter came. There was a table with the legs shortened, and a chair with the legs shortened. There was a rough bookstand and real books on the shelves, and on top of the stand were four dolls.

One doll was the exact likeness of her mother. Another was the image of Mr. Wootton. The third was a lovely young woman with straight black hair and large dark-brown eyes, and the fourth was an elderly man with weak blue eyes, a long face, and drooping grey moustache.

Linda stood before the dolls, and said:

“Meena! What’s the date? No, it’s not February 10, Meena. You should know the date. You went to Mission School. All right. Ole Fren Yorky, you tell me the date. February 9! Of course it isn’t February 9.” Linda glared at the doll with the weak blue eyes and the absurdly drooping grey moustache. She mimicked her mother: “Ole Fren Yorky, I’m asking you to tell me the date to-day. Oh dear! Won’t you ever learn!”

So the converse with the four dolls continued over a wide range of subjects, including a box of chocolates with nuts on top, and lace-edged hankies with the letter L in the corner. She was seated in the chair, the dolls on the table before her. She had straightened Mr. Wootton’s tie, and had combed Meena’s hair, and was intently trying to twirl points of Ole Fren Yorky’s moustache when the report of a rifle obliterated the low buzzing of the blowflies.

“Now, Ole Fren Yorky, stay still,” she scolded. “Your moustache is getting disgraceful. That’ll be Mr. Wootton out there shooting the crows. You know very well how naughty they are, and have to be shot sometimes.”

Ole Fren Yorky wouldn’t be still, and Linda had to concentrate on gaining compliance with her efforts. Minutes later, she remembered that Mr. Wootton had left an hour before for Loaders Springs. A tiny frown puckered her dark brows. She pushed Ole Fren Yorky to one side, and had put her hands to the table to push her chair away from it, when there appeared in the doorway the original Ole Fren Yorky.

Terror leaped upon her. The man’s weak blue eyes were now hot and blazing. He ran forward, a light swag at his back, a rifle in his left hand. Linda sprang out of the chair, and then found herself unable to move. A bare arm gripped her about the waist and she was lifted. She opened her mouth to scream, and her face was pressed hard into a sweaty chest, and no longer was it just another day.

CHAPTER 2

Murder in Eden

Until four o’clock it was just another day for Arnold Bray.

Like many big men, Bray was deliberate in thought as well as action, and this led people to believe him to be slow in both. Under thirty, he received the respect of men of his class much older than himself, and from men much younger who noted his powerful physique.

He was that asset to all pastoral properties—the man of all trades, and it was quite unnecessary for Wootton to advise him how to remove iron sheets from a roof. The building to which he drove this day was situated some twelve miles from the Mount Eden homestead, and had been used as a shearing shed in a period when sheep were reared, only to be severely attacked by wild dogs. In this land where rust is reduced to a minimum by the dry atmosphere, the roof iron was worth salvaging.

By three o’clock Arnold had removed enough iron for a sound load, and, having lashed it securely from the high wind he would encounter on leaving this shelter amid tall blue gums, he took time to boil water and brew a quart pot of tea. It was three-thirty when he called the dogs into the truck cabin and started for the homestead.

Once beyond the trees, the wind buffeted the load and made steering on the narrow and little-used track something of a task. The truck hummed powerfully as it moved up a long and gradual slope to the summit of the highlands, which were never more than two hundred feet above the lowlands marked so clearly by creek and swamp and depression. Here on the bare slopes lay vast areas of ironstone gibbers, closely packed like cobbles, evenly laid into the cement base of earth-clay, and so polished by the wind-driven sand grains that they reflected the sunlight in a glassy glare.

Here, this day, earth and sky merged without an horizon. Arnold could not have seen the summit of the long slope had he looked for it, so masked was this world of open space and wind and dust by the distortion of sunlight. A tall solitary tree became a mere broken sapling; a boulder reached in a few seconds had appeared to be a dozen miles distant; what had seemed to be a barrier of sand was actually a faint fold in the earth.

Abruptly, in front of Arnold’s truck was the homestead; the square of buildings, the line of pines, the braked windmills, all like a picture left upon the floor and covered with the dust of years-long neglect. Yet the homestead was two hundred feet below the truck, and a mile away.

The wind was blowing to the truck, a gusty wind which stockmen would find slightly unpleasant, not unbearable. The two dogs squatting on the seat beside the driver were happy until but half a mile from the homestead. Then, at the same time, both tensed, began sniffing, finally joined in a chorus of low lament.

Arnold could see Eric mounted on his horse, and the horse was standing almost motionless in the centre of the square fashioned by the buildings. The animal’s legs seemed a hundred feet high, and Eric appeared to be sitting on a barrel, causing Arnold to chuckle, because never was he bored by the tricks played by this remarkable land.

Attracted by the dogs’ behaviour, wondering at the stockman’s most unusual stance, Arnold pressed on the accelerator, arriving at the motor shed, where the iron was to be stacked, in a cross cloud of dust and squealing brakes. Eric dismounted, and led his horse to the man standing beside the grounded dogs.

“Been hell to play,” he said, the slow voice failing to hide shock. “No one here but her. The kid . . . I can’t find the kid. Mrs. Bell’s over by the kitchen door. I covered her up. I . . .”

“What happened?” asked Arnold, his steady voice not matching the concern in his eyes.

“Don’t rightly know. Exceptin’ that Mrs. Bell’s been shot dead. The boss . . .”

“Was set to leave for town,” supplemented Arnold. “Let’s look see. How long you been back?”

“Quarter-hour, half-hour, I don’t know. I got to the yards and saw the crows by the kitchen door where no crows oughta been. So I rode over and saw what it was. I yelled and screamed for the kid, but she didn’t come out from nowhere. And no one else either. I don’t get it. I tell you, Arnold, I don’t get it.”

“We will. Anchor that horse somewhere. Wait! Keep the horse. May want it in a hurry.”

Arnold glanced at his shadow, subconsciously noting the time, recalling that his employer usually returned from town between five and six. A great number of crows were circling about, dozens more were perched on the house roof and on the round roof of Linda’s playhouse. What they had done to the dead woman’s neck and arms . . . It was Mrs. Bell without a shadow of doubt. Arnold gently replaced the bag over the body and stared into the troubled eyes of the rider. The dogs slunk away. Eric said:

“I did right covering her? Then I got back on my horse and shouted for Linda. Got the jitters sort of. Expected someone to shoot me. What’re we to do?”

“Find the kid. Where have you looked?”

“Nowhere. Just shouted. Them crows! She musta been shot this morning.”

“Take a hold, Eric.” Arnold’s voice was quiet, and it calmed Eric Maundy. The slight twitching of his lips firmed to grim anger. “We’ll look-see in the house first; there’s no one else around, accordin’ to them crows.”

Inside the kitchen, they called for the child, waiting for her reply. Here, where the wind was baffled, the silence was hot and familiar. Their shouts fled away into the rooms beyond, to crouch in corners and wait for them. When they entered the spacious living-room they were halted by the wreckage of the expensive transceiver, and by the smashed telephone instrument. It was the first time Eric had been there, but Arnold had often serviced the telephone.

There was no further damage. Nothing had been disturbed. Eric found the axe with which the instruments had been destroyed, lying under a chair where it had been carelessly flung.

The dust was crossing the open square, tinting the buildings, brazing the hard clay ground. Above, the crows were streaking black comets against the glassy roof of white flame. Eric said:

“More ruddy crows than when we kill a beast. Blast ’em!”

Arnold made no comment, and Eric followed him in a further systematic search, beginning at the canegrass meat-house, trying the locks of the office and the store room, proceeding to the playhouse.

The four dolls were on the table, Ole Fren Yorky toppled and lying on his back. The place was in its usual tidy disorder, familiar to both men. There was nowhere here for Linda to hide. Leaving, they looked under the floor, knowing they could see beyond the structure, hoping against vanquished hope. They had finished with the men’s quarters, a building containing four bedrooms and a common-room, when Arnold saw young Harry Lawton dismounting at the stockyard gates.

His shout stopped the young man from freeing the horse, brought him to them, large spurs jangling, red neckerchief flapping.

“You’ll want your horse,” Arnold said. “There’s been a shooting. Mrs. Bell is dead and Linda has vanished.”

“Hell!” exploded Harry. “Linda couldn’t have shot her ma. What else happened?”

“Ain’t that enough?” demanded Eric, and waited for instructions from Arnold.

“You fellers get going. Ride around. Look for tracks. Look for . . . you know. Look for Linda. Somebody came after the boss left for town. The bloody crows didn’t shoot Mrs. Bell.”

They obeyed without question that steady authoritative voice, and Arnold went back to the quarters and leaned against the front wall and chipped at a tobacco plug. He was cold deep down in his mind, so enraged that, now no one was near to see, his grey eyes were wide and blazing.

The question tormented him. Who had done this grim thing? A traveller? Hardly. No tracks went beyond Mount Eden, save the little-used track to the old homestead called Boulka, and he himself had just come in by that track. A traveller was as rare as an iced bottle of beer on the centre of Lake Eyre. All the blacks were away on the Neales River, fifty miles to the north. The nearest town, Loaders Springs, was more than forty miles to the south-west, and the nearest homestead was something like a hundred and ten miles away round the southern verge of the lake.

There was left . . . what? Five white men who had eaten breakfast here at Mount Eden, and any one of those men, including himself, could have returned, unknown to the others, and murdered the woman. And the kid? No . . . no! That Arnold wouldn’t accept. Every man of them loved Linda. Knowing he would find no tracks, Arnold yet sought for the tracks of strangers, or tracks betraying unusual movement out of time.

He was trudging about the hard, sand-blasted ground when Bill Harte joined him. Neither spoke, both staring into the eyes of the other. Harte was small, wiry, bowlegged and iron-fisted. Under the weathered complexion lay the barest hint of mixed ancestry. The tight lips parted in what could have been a snarl, but his voice was low and clipped.

“Met Eric on the way in,” he stated. “Told me. No sign of the girl?”

“No sign of anything, Bill. You see around. You’re better than I am at it.”

They walked to the body, and Harte lifted the bag.

“She was running when she was shot,” he said. “She was running from the kitchen door, and whoever shot her was standing in the doorway. Betcher on that. Prob’ly was runnin’ to grab up Linda. Linda musta been in her playhouse when it happened. You looked there, of course?”

Arnold didn’t reply to the obvious. Harte moved away, almost at the run, crouching to bring his eyes closer to the ground, and the big man, watching, realised that he was a mere amateur tracker beside Bill Harte. All the others were superior to him, too, but then all of them together knew less than he of welding iron or repairing a pump.

What to do now? Something had to be done with the body. It had lain there for hours, and the ants were investigating it. Arnold judged by his shadow that it was close to five o’clock, when Wootton’s return could not be far off. Harte was running about the outbuildings like a distraught dog. The others were nowhere in sight. Yes, something had to be done beside just standing about. The boss might be late, mightn’t get back till after dark.

From the carpenter’s shop he brought several wooden pegs and a hammer. The pegs he hammered into the hard ground so that they outlined the body, then he dusted the ants from it, turned it over, and for a space looked down upon the pained face and the wide grey eyes in which revolt against death was so plain.

Without effort, Arnold Bray took up the body and carried it to the woman’s bedroom, where he placed it on the bed and then found a spare sheet with which to cover it. Cover the Dead. . . . She had been a good woman, above him in so many things, a woman he had admired humbly when there had been women he had admired, but not humbly. The possible motive for this thing, so much worse than mere murder you read of in the papers, persisted in entering his mind, although he fought it back with savage anger. And so preoccupied was he by the futility of it all that without conscious animation he drew the blind, and then passed from room to room to draw down every blind.

Bill Harte called from the rear door, and Arnold went to him, hope reborn, and slain again when he looked into Bill’s eyes.

“Come with me,” Harte said, harshly. “You check.”

He led the way to the underground tank which had cemented floor and walls and a canegrass roof rising to a pyramidal summit. From this place he proceeded a dozen steps to the rear of the meat-house, where he halted and stared at the ground against the grass wall in the lee.

“What d’you see?” he demanded.

Arnold saw nothing at first, save the imprints of a dog. Then larger prints appeared to grow on the light-red ground, so that the dog’s prints faded into insignificance. What now he was seeing were three prints made by a man’s boots. They were unusual in that there were no heel marks.

“You musta seen those prints some time or other,” Bill stated.

“If I did I don’t recall them,” admitted Arnold. “Still, they look like the prints of a man running. No heel marks. I know! Ole Fren Yorky walks like he’s always running. They’re his tracks.”

“Yair. Yorky made ’em.”

“But Yorky’s in town on a bender.”

“Couldn’t be. Yorky made them tracks four-five hours ago. That right what Eric says about the telephone and the transceiver?”

Arnold nodded. He said with sudden determination:

“I’m driving the truck to meet the boss. He’ll have to go back to town to report to Pierce and bring men out to join in the hunt for Yorky. Yorky’s got Linda . . . if he hasn’t killed her. Yorky’s got to be nabbed, and quick. If he’s killed Linda you keep him away from me.”

CHAPTER 3

The Deceitful Land

Within minutes of a crime being reported in a city, a superbly organised Police Department, backed by modern scientific aids, goes into action. It was not to the discredit of Senior Constable Pierce that he was thwarted by inability to see without lights over an area of something like ten thousand square miles of semi-desolation; because the weather was against him in a land where the weather can aid or baffle keen eyes and keen brains.

He arrived with the doctor from Loaders Springs shortly after nine on that night following the murder of Mrs. Bell. It was then black night, the stars blotted out by dust raised all day by the mighty wind. Before dawn a new transceiver was working at the Mount Eden homestead, and a new telephone installed. At dawn two trucks left to locate the aborigines and bring back all the males, to be put to tracking. Soon after dawn cars and trucks began to arrive, bringing neighbours from homesteads fifty, sixty, a hundred miles distant, and at dawn other men rode out from homesteads still farther distant to patrol possible lines of escape for the murderer of Mrs. Bell, and the abductor of her daughter.

The man called Ole Fren Yorky, born in Yorkshire, brought to Australia when he was fifteen, outwitted bushmen reared in this vastness of land and sky, and the native trackers of whom the world has no equal. His tracks were discovered at the vacated camp of the aborigines situated less than a mile from the homestead, and beside the canegrass meat-house within yards of the house kitchen door; those two places sheltered by the wind. He carried a Winchester .44 repeating rifle, and the woman had been shot by a bullet of this calibre.

Men discussed the motive, but more important was the finding of Linda Bell, alive or dead. Her fate was of paramount importance, for until the child’s body was found, hope remained in the hearts of the hunters.

The initial verve of the hunters gradually degenerated into doggedness. The aborigines lost interest, rebelled against the driving of the white men, as though convinced that Yorky, with the child, had won clear of their ancient tribal grounds.

The white force dwindled, men being recalled to their homesteads to attend chores which could no longer be neglected, and at the end of four weeks the organised search was abandoned.

Three days after Constable Pierce informed Wootton of the official abandonment of the search, the station owner was told of the coming of another policeman. Wootton had engaged Sarah, from the aborigines’ camp, as cook, and Sarah’s daughter, Meena, as maid, and the routine of the station was as though interruption had never been when this morning, as usual, Meena brought to the living-room table the large tray bearing Mr. Wootton’s breakfast. Cheerfully he said “Good morning”, and, shyly demure as usual, Meena responded.

Meena was in her early twenties. She had lost the awkward angularity of youth, and was yet distant from ungainliness reached early by the aborigines. Not a full blood, her complexion was honey, and her features were strongly influenced by her father, even her eyes being flecked with grey. Wearing a colourful print dress protected by a snow-white apron, her straight dark hair bunched low on her neck, and with red shoes on her feet, she was an asset to any homestead, and, in fact, was appreciated by Mr. Wootton. Her voice was without accent, soft and slow.

“Old Canute say for me to ask you for tobacco in advance. He’s been giving too much to Murtee, and Murtee says he used his to stop old Sam’s toothache.”

“Sam’s toothache, Meena!” exclaimed Mr. Wootton. “Why, old Sam must have lost his last tooth fifty years ago.”

“Old Sam lost his last tooth before I was born. But old Canute’s run through his tobacco. He says if Mr. Wootton won’t hand out, then tell Mr. Wootton what about a trade.”

“A trade! Explain, Meena.”

“Canute says for you to give him a plug of tobacco, and he’ll tell you something you ought to know.”

“Oh,” murmured Mr. Wootton. “Sounds like blackmail to me. D’you know what this something is I ought to know?”

“Yes, Mr. Wootton. I know. Canute told me.”

“And you won’t tell unless I promise to give that wily scoundrel a plug of tobacco?”

The expression of severity on the cattleman’s face subdued Meena. For the first time she shuffled her feet on the bare linoleum. She spoke two words revealing the unalterable position she occupied.

“Canute boss.”

Wootton’s experience of aborigines was limited, but he did know the force and authority wielded by the head man of a native clan, and thus was aware that the girl was behaving naturally, was merely a go-between as the messenger between Canute and himself. Severity faded from his green eyes.