1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Bony is happy to take on a little informal investigation during his vacation in Western Australian, after a farmer suddenly disappears near a huge wheat field. Despite the lack of evidence, Bony suspects murder - which leads him to uncover some strange goings-on.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

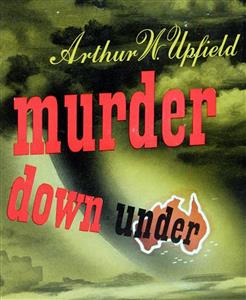

Murder Down Under

by Arthur W. Upfield

First published in 1937

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Murder Down Under

by

Contents

CHAPTER

PAGE

I

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Holiday

1

II

An Ordinary Wheat Town

9

III

The Wheat Belt

19

IV

Mr. Jelly

30

V

Theories

41

VI

“

The Spirit Of Orstralia

”

52

VII

Within Another World

63

VIII

The Dance

78

IX

Mr. Poole

91

X

Bony Is Entertained

101

XI

Dual Mysteries

115

XII

Note Series K/11

126

XIII

Bony’s Invitations

133

XIV

Mr. Thorn’s Ideas

150

XV

Secrets

157

XVI

Mr. Thorn’s Plant

174

XVII

After the Dance

182

XVIII

Bony Is Called In

193

XIX

Mr. Jelly Is Shot

209

XX

The Return of John Muir

217

XXI

Needlework

228

XXII

Lucy Jelly’s Adventure

242

XXIII

Trapped

254

XXIV

Mrs. Loftus Passes On

263

XXV

The Rabbit—and the Hunters

273

XXVI

Finalizing a Case

284

XXVII

Landon Answers the Riddle

295

Introduction

For many years Arthur W. Upfield has been the leading mystery-story writer of Australia in regard to both productivity and popularity. We, as his American publishers, have an unusual pride in introducing him here. There have been instances where a series of books by foreign writers were projected onto the American scene. In most of these cases translation was involved. With Upfield there is no such question, of course, but there is a completely different background, an unusual narrative style, a different idiom, and a by no means run-of-the-mill central character. To American ears the style has a rather formal sound which makes it doubly interesting, since the facts and details of the story are completely of the present day and there is an interlarding of Australian back-country slang.

We have not felt it necessary to include footnotes or glossaries for any of the unusual words used. In a book of entertainment such as a mystery story it has always seemed a little self-conscious to point up an unusual word. We feel that the connotation is obvious from the context. In one or two cases, when a word has a diametrically opposed meaning to American readers, we have dropped it and substituted a more familiar one.

In this book, as well as in other books by Mr. Upfield which we plan to publish at frequent intervals, there is a picture drawn of Australian life which is bound to interest Americans now more than at any other time. Because of the thousands of Americans now in Australia with our armed forces, that country has become to many of us the most intriguing, important part of the globe, and we welcome an opportunity to meet its people and its scene through an informal, intimate medium such as the detective story.

The central character, Detective-Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte, will, we prophesy, join the group of fictional detectives who are so well known that their admirers feel they exist in person. Bony has many individual characteristics which will easily differentiate him from any other of these book-cover sleuths. To a high degree he is the modern, expertly trained police investigator. In combination with these capacities he has his inborn talents: intuition, observation, and a feeling for the bush country which an outlander could never have.

In Murder Down Under Bony went to Western Australia to investigate the disappearance of George Loftus, whose car was found wrecked near the longest fence in the world, the 1500-mile-long Rabbit Fence. Bony met Loftus’ wife, who spared no grief at his disappearance; his hired man, singularly reticent about his own past history; the personnel of the town that was an active wheat and gossip center. Later he met Mr. Jelly, whose mysterious business caused his two charming daughters great anxiety. It was the double question of George Loftus’ disappearance and Mr. Jelly’s business which kept Bony on the job until the two problems were solved at the same time.

Murder Down Under has a flavor and feeling for a land unlike our own in many respects but with a curious similarity to our own Western “not far removed from the pioneer” country. The speech, slang, and customs add much in the way of freshness and entertainment to a sound detective mystery.

The Crime Club

map

CHAPTER I

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Holiday

If it had not rained! If only the night of 2 November had been fine! Raining thirty points that most important night was sheer cursed bad luck.

John Muir sauntered along the south side of Hay Street, Perth, heedless of the roaring traffic and of the crowd. To him the life and movement of the capital city of Western Australia was then of blank unconcern; of greater moment was the heavy shadow of failure resting on his career. To the average ambitious man temporary failure may mean little, and that little but the spur to the posts of achievement; failure now and then interposed among marked successes to one of Muir’s profession merely delays advancement; but failure repeated twice, one treading on the heels of the other, raised the bogey of supersession.

Detective-Sergeant Muir was not a big man as policemen go. There was no hint of the bulldog about his chin, or of the bull about his neck. Although he walked as walks every officer in the Police Force, having attended that school of the beat in which every constable is enrolled, John Muir in appearance looked far less a policemen than a smart cavalryman. Not much over forty years old, red of hair and complexion, he did not seem cut out to be a victim of worry: worry crowned him with peculiar incongruity. So deep were his cogitations about the weather that it was not the hand placed firmly on his left shoulder, nor the words spoken, but the soft drawling voice which said:

“Come! Take a little walk with me.”

It was a phrase he himself had often used, and the fact that other lips close to his ear now uttered it produced less surprise than did the well-remembered voice. The drabness of his mood gave instant place to the lights of the world about him. He swung towards the curb, caught the arm of the man whose hand was upon his shoulder, and gazed with wonder and delight into a pair of beaming blue eyes set in a ruddy brown face.

“Bony! By the Great Wind! It’s Bony!”

“I at first thought you were the ghost of the Earl of Strafford on his way to the block,” Detective-Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte said gravely. “Then I was reminded of poor Sindbad the Sailor, wearied by the old fellow who so loved him. Why the mantle of gloom this bright Australian morning?”

“Where were you the night of the second of November?” demanded John Muir, his grey eyes twinkling with leaping happiness.

“November the second! Let me think. Ah! I was at home at Banyo, near Brisbane, with Marie, my wife, and Charles, and little Ed. I was reading to them Maeterlinck’s——”

“Did it rain that night?” Muir cut in as though he were the prosecuting counsel at a major trial.

His mind being taken back to the night of importance by Muir’s first question, Bony was able to answer the second without hesitation.

“No. It was fine and cool.”

“Then why the dickens couldn’t it have been fine and cool at Burracoppin, Western Australia?”

“The answer is quite beyond me.”

Detective-Sergeant Muir, of the Western Australian Police, slipped an arm through that of Detective-Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte, of the Queensland Police, and urged his superior across the street. The delight this chance meeting gave him, resulting in this impulsive act, suggested to the constable just behind them that the quietly dressed half-caste aboriginal was indeed taking officially a little walk with the detective-sergeant. He became puzzled when the two entered a teashop on the opposite side of the street.

They were fortunate to secure a table in a corner.

“The fact that it rained a certain night at a particular place seems to perturb you,” Bony remarked, with his inimitable blandness, after tea and cakes had been set before them.

“What are you doing here?” Muir asked with a trace of anxiety.

“Waiting for you to pour out my tea.” Bony’s deep blue eyes shone quizzingly. Perfect teeth gleamed between his lips when he spoke. His fine black hair, well brushed, had the lustre of polished ebony.

“Well, what are you doing here in the West?”

“Impulsive as ever, John. Your head is full of questions as uncontrollable as the tides. After all my interest taken in your career, despite my careful coaching extending over a period of eight years, in spite of your appearance, which is less like that of a policeman than any policeman I know, you flagrantly give away to even the most unsuspecting person your precise profession through your excessive questionings.”

John Muir laughed.

“By the Great Wind, Bony, old chump, I’m glad you are with me in this teashop,” he exclaimed with dancing eyes. “I’ve been wanting one man in all the world to get me out of a thunderin’ deep hole, and lo! that man whispers into my ear’ole: ‘Come, take a little walk with me.’ But tell us the story. How is it you’re in Perth just when I needed you?”

Muir was like a youth in the presence of a generously tipping uncle. Softly Bony murmured:

“I am here because you wanted me.”

“You knew it? How did you know?”

“You made a tangle of the Gascoyne affair, didn’t you?” Bony countered accusingly.

“Ye-es, I am afraid I did.”

When next he spoke Bony’s gaze was centered upon his plate.

“After all my tuition you took a creek without first ascertaining the depth of the water. You accepted a conclusion not based on logical deduction. You ignored science, our greatest ally after Father Time. It was unfortunate that you arrested Greggs, wasn’t it?”

John Muir mentally groaned. Bony, looking up swiftly into his grey eyes, saw once again the shadow.

“You see, John, I have been following your career closely,” he went on in his calm, pleasant manner. “Because a man’s trousers are bloodstained, it does not follow that the blood on them is human blood. Granted that at the time you did not know Greggs was a sheepstealer supplying the local butcher with cheap meat, you should, however, have walked slowly, making sure that the stains of blood were human or animal, and making equally sure Greggs did not get away whilst you were walking. Jumping thus to a most unscientific conclusion, which that great mathematician, Euclid, would have bitingly termed absurd, you permitted Andrews to get clear away.”

“I know, I know! What a fool I was!”

“Hardly a fool, John, but too impetuous. And now, why your worry regarding the weather during the night of November the second?”

Again sunlight chased away the shadows. From an inside pocket John Muir produced a wallet, and from the wallet a roughly drawn plan, which he laid before Bony.

“Here’s a drawing of a wheat town and locality named Burracoppin, one hundred and eighty miles east of Perth on the gold fields’ line,” the sergeant explained. “For eight days prior to the second of November a farmer named George Loftus was down here in Perth on business and pleasure. The licensee of the Burracoppin Hotel, Leonard Wallace met Loftus in Perth during the afternoon of November the first, and Loftus, having unexpectedly completed his business, offered Wallace a lift to Burracoppin the next day.

“They left Perth at ten o’clock, and, as Loftus’s car is a light one, it was ten o’clock that night when they arrived at Wallace’s pub. After supper they went to the bar and stayed there drinking until one o’clock. By that time, according to Wallace, they were both well down by the stern. He says that when they went out to the car it was raining, and he urged Loftus to stay the night. But Loftus appears to be a pigheaded man in drink, and, drunk as he was, determined to drive home. Wallace, deciding to go with him, induced Loftus to wait while he informed Mrs. Wallace. She heard them set off at ten minutes past one.”

With a stub of pencil Muir indicated the plan.

“When they left the hotel Loftus drove along the main road eastward. At the garage he should have turned south to the old York Road, a mile farther on, which would have brought him to the Number One Rabbit Fence in about another mile. This night, however, Loftus drove straight on east, following the railway, and Wallace expostulated, as this road was in bad condition. They had proceeded a quarter of a mile, still arguing, when Loftus stopped the car and ordered Wallace to get out. He then drove on alone, according to Wallace. He had about one mile to travel before reaching the Rabbit Fence, where he would turn south, traverse it for another mile, cross the old York Road, and after covering a third mile would arrive opposite his farm gate.

“But he never reached home. He crashed into the Rabbit Fence gate, and, when backing his car, backed the car into the State Water Supply pipe line, which at that place runs along a deeply excavated trench. The car was smashed badly, of course. It was impossible for Loftus to get its back wheels up out of the trench. His hat was found beside the car, and Wallace’s hat was found on the back seat. Close by were two newly opened beer bottles.

“Of Loftus there had been no sign since Wallace, as he alleges, parted from him about 1.20 a.m. A search lasting twelve days has produced no result. If only it hadn’t rained thirty points the black tracker, brought from Merredin, would have picked out Loftus’s tracks, and have found him dead or alive.”

Muir ceased talking.

“Well?” urged Bony.

“The funny part about the affair is the time Wallace reached home. When he alighted from the car they were less than half a mile from the hotel. They left the hotel, remember, at one-ten. It would be one-twenty, no later, when they parted company, yet it was two-fifteen when he entered his bedroom, according to Mrs. Wallace. He states that when Loftus drove away he walked back as far as the garage turning; there, feeling the effects of too much grog, he turned up along the south road for a walk.

“I think he did nothing of the sort: it doesn’t sound reasonable. Yet what did he do during those fifty-five minutes? He wouldn’t require fifty-five minutes to walk back to his home, a distance of less than half a mile. But if the two were together at the time of the smash, if they fought and Wallace killed Loftus, there was time to hide the body and get back home at the time Mrs. Wallace said he did.”

“You have not found a body?” interposed Bony.

“No.”

“Then until a body is discovered we must assume that Loftus is still living. Has Wallace a record?”

“Nothing against him.”

“You are sure that Loftus did not reach his home?”

“Quite. Mrs. Loftus is frantic about him.”

“Is the car still wedged above the pipe line?”

“Yes.”

“Why not arrest Wallace on suspicion?”

“Not on your life. Greggs was enough,” John Muir said fervently. “In future I’m creeping that slow and sure that a turtle will be a race horse against me.”

“Overcautiousness is as big a fault as impetuosity,” Bony said with sudden twinkling eyes. “Your Burracoppin case captures my interest.”

“Will you lend a hand?”

Bony sighed.

“Alas, my dear John! You will have to go to Queensland.”

“To Queensland! Why?”

“If you go to Myall Station, out from Winton,” Bony said slowly, “if you proceed circumspectly, you will there find your lost friend, Andrew Andrews, whom you let slip away because you were so sure of Greggs. As the delightful Americans say, ‘Go get him, John!’ ”

“But why didn’t you have him arrested or arrest him yourself?” demanded Muir, so much astonished that he swayed back in his chair.

“Not being an ordinary policeman, but a crime investigator, I seldom make an arrest, as you well know. Arresting people is your particular job, John. We will tell a tale to your commissioner. We will persuade him that getting Andrews is of greater importance than finding Loftus, who, after all, may be playing a game of his own. I have still three weeks of my leave remaining, and, while you are away in Queensland, I will look after your interests in Burracoppin.”

“Bony, old man, how can I——”

“Don’t,” Bony urged with upraised hand. “I often enjoy a busman’s holiday. Between us we will make them promote you to an inspectorship. But curb your desire to question. It is your greatest fault. Curiosity has harmed other living things besides cats. Read Bunting’s ‘Letters to my Son.’ He says——”

CHAPTER II

An Ordinary Wheat Town

In the investigation of crime Napoleon Bonaparte was as great a man as was Lord Northcliffe in the profession of journalism. Like the late Lord Northcliffe Bony, as he insisted upon being called, interested himself in the careers of several young men of promise. John Muir was one of Bony’s young men, having learned the rudiments of crime detection by valuable association with the little-known but brilliant half-caste. Yet of his several young men the Western Australian detective-sergeant was the slowest to learn Bony’s philosophy of crime detection. Although he knew it by heart he often failed to act on it, and consequently Bony’s advice was often repeated:

“Never race Time. Make Time an ally, for Time is the greatest detective that ever was or ever will be.”

Together they gained an interview with the Western Australian Commissioner of Police. By previous agreement Bony was permitted to do most of the talking. He melted Major Reeves’s reserve, which his duality of race had created, with his cultured voice, his winning smile, and his vast store of knowledge that now and then was revealed beyond opened doors. He charmed John Muir’s chief as he charmed everyone after five minutes of conversation.

The interview resulted in Major Reeves believing that John Muir had traced the murderer, Andrew Andrews, with the slight assistance rendered by the Queenslander. He consented to send his own man to Queensland and permit Bony to interest himself in the Burracoppin disappearance. It thus came about that Bony and Muir left Perth together by the Kalgoorlie express, the former alighting at the wheat town at five o’clock in the morning, and John Muir going on to the gold fields’ terminus where he would board the transcontinental train.

Day was breaking when the express pulled out of Burracoppin, leaving Bony on the small platform with a grip in one hand and a rolled swag of blankets and necessaries slung over a shoulder. No longer existed the tastefully dressed man who had accosted Detective-Sergeant Muir in Hay Street. In appearance now Bony was a workman wearing his second-best suit.

At this hour of the morning Burracoppin slept. The roar of the eastward-rushing train came humming back from the yellowing dawn. A dozen roosters were greeting the new day. Two cows meandered along the main road, cunningly putting as great a distance as possible between themselves and their milking places when milking time came. A party of goats gazed after them with satanic good humour.

When Bony emerged from the small station he faced southward. Opposite was the Burracoppin Hotel, a structure of brick against the older building of weatherboard which now was given up to bedrooms. To the left was a line of shops divided by vacant allotments. To the right the three trim whitewashed cottages, with the men’s quarters and trade shops beyond, owned by the State Rabbit Department. Behind Bony, beyond the railway, were other houses, the hall, a motor garage, and the school, for the railway halved this town; and running parallel with the railway, but below the surface of the ground, was the three-hundred-miles-long Mundaring-Kalgoorlie pipe line conveying water to the gold fields, and, through subsidiary pipes, over great areas of the vast wheat belts. Thus is Burracoppin, a replica of five hundred Australian wheat towns, clean and neat, brilliant in its whitewash and paint and its green bordering gum trees.

Till seven o’clock Bony wandered about the place filling in time by smoking innumerable cigarettes and pondering on the many points of the disappearance of George Loftus contained in the sixteen statements gathered by John Muir. The case interested him at the outset, because there was no apparent reason why Loftus should voluntarily disappear.

A man directed him to a boardinghouse run by a Mrs. Poole. At that hour the shop in front of the long corrugated-iron building was still closed, but he found the owner in the kitchen at the rear, where she was busy cooking breakfast. Mrs. Poole was about forty years old, tall and still handsome; a brunette without a grey hair; a well-preserved woman of character. Into her brown eyes flashed suspicion at sight of the half-caste, at which he was amused, as he always was when the almost universal distrust of his colour was raised in the minds of white women—instinctive distrust which invariably he set himself to dispel.

“Well!” Mrs. Poole demanded severely.

“I arrived this morning by the train,” he explained courteously. “A townsman tells me this is the best place in town at which to get breakfast.”

“It’ll cost you two shillings,” the woman stated in a manner denoting doubt of his ability to pay.

“I have a little money, madam.”

Sight of the pound note Bony produced changed Mrs. Poole’s expression. The change he hoped was caused by his accent. Mrs. Poole produced cup and saucer and seized the teapot.

“Thank you,” he said, gratefully accepting the cup of tea. Offering the treasury note, he added:

“It might be as well for you to take that on account. I may be in Burracoppin for some time. As a matter of fact, I have got a job with the Rabbit Department.”

“You have!” Obviously Mrs. Poole was pleased. “Then you will be boarding here, I hope?”

“For my meals, yes. I understand, however, that sleeping quarters are provided by the department at the depot.”

“Yes, that’s so.” Quick steps sounded from without. “Oh my! Here’s Eric.”

A man entered as might a small whirlwind from the plains of Central Australia.

“Ah, late again! Mrs. Poole. Quarter past seven, and breakfast not ready. When is that husband of yours coming back? Every time he’s away you hug that bed, don’t you? You’ll die in it one of these days. Now, don’t argue. Get on—get on. No burgoo for me. There’s no time to eat. I’ll be getting the sack for being always late.”

The whirlwind was dressed in dungaree overalls. Keen hazel eyes examined Bony humorously.

“Good morning,” Bony said.

“Going to work for the Rabbits,” interposed Mrs. Poole.

“Oh! Well, I’d advise you not to board here. Better stop at the pub. Mrs. Poole’s husband is a Water Rat, and sometimes he’s away for weeks on end. When he is away Mrs. Poole hardly ever leaves her bed, she loves it so. You only get one minute ten seconds to gollop your breakfast, but you do get plenty of indigestion. I’m half dead already.”

“I’m not as bad as all that, Eric,” pleaded Mrs. Poole in a way which decided Bony that he was going to like his landlady. To him she added: “Don’t you believe him, Mr.—what is your name?”

“Bony.”

“Sometimes I’m late, Mr. Bony, but not always. Will you take porridge?”

“Please.”

“You married?” inquired the subsided whirlwind.

“Yes.”

“Then you’ll be Mister Bony henceforth. All married men here are called misters, and single men are called by their Christian monikers. I’m Eric Hurley, unmarried, and, therefore, plain Eric. What’s yours?”

“Xavier,” replied Bony blandly. “But everyone calls me Bony without the mister. I prefer it.”

“Just as well. Xavier! Hell! Bony will do me. Come on! We’ve only got forty seconds. Shoot in that tucker, Mrs. Poole. Come on. Get going.”

In the dining room between kitchen and shop the two men ate rapidly. Hurley, Bony observed, was not much beyond thirty years old. He liked his open face, lined and tanned by the sun and lit with the optimism of youth.

“I’m the boundary rider on this section of the Rabbit Fence,” Hurley explained between bursts of rapid mastication. “I’ve got two hundred miles of it to attend to—a hundred miles north and south of Burracoppin. When the depression crash came all hands bar ex-soldiers were sacked. Hell-uv-a job. For each Sunday on the job I get a day off here. But I’m workin’ today, as the farm push are shorthanded, and there’s a chaff order to be sent away. Hey, Mrs. Poole! My lunch ready?”

“I’m cuttin’ it now.”

“Make it big. I haven’t time to eat a decent breakfast.” From the railway yard came the sound of a petrol engine. Through the window they saw the motor-propelled trolley sliding away loaded with permanent-way workers. “Hurry! Hurry! The Snake Charmers have gone. If I’m sacked for being late I’ll murder your husband and take his place. And I won’t get up and light the fire for you. I’ll kick you out of bed.”

A tin rattled. The whirlwind rushed out. There was silence. Then Mrs. Poole’s voice was raised urging someone to get up and fetch the cows before Mrs. Black got them and “sneaked” the milk. She came to the door.

“Don’t you hurry, Mr. Bony. The Inspector isn’t so sharp as Eric makes out. You see, my other boarders all work about the town and never come to breakfast till a quarter to eight. This place is easier when Joe’s at home, what with the woodcutting and the cows, an’ that Mrs. Black who always tries to milk them first. And I’ve been busy lately. I’ve had two policemen staying here ever since poor Mr. Loftus disappeared. They are gone now, back to Perth.”

“Oh!”

“It’s funny, that affair,” she went on. “I’m sure he’s been murdered. Eric was camped half a mile from his house that night. Although it was raining, it was quiet, and he could hear the dogs howling about two in the morning. When my sister had her husband killed on the railway, down near Northam, her dog howled awful for more than an hour. Dogs know when their friends die—don’t you think so?”

Fifteen minutes after Bony left Mrs. Poole’s boardinghouse he was watching the changing expressions on the face of the Rabbit Fence Inspector while that official read the letter written by the chief of his department and delivered by the detective.

“You are a member of the Queensland Police Force?”

Bony inclined his head.

“I am instructed to assist you in every way. What can I do?”

“Permit me to explain. I am a detective-inspector, at present on leave. My friend, Detective-Sergeant Muir, has been obliged to go into another matter, and, as the disappearance of George Loftus interests me, I have decided, with the sanction of the Western Australian Police Commissioner, to look into it. Outside police circles, your chief and yourself are the only people in this State who know I am a police officer. I rely upon you to keep my secret. People talk and act naturally before Bony, but are as close as oysters in the presence of Detective-Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte. I want you to give me employment on the Rabbit Fence, preferably near where Loftus’s wrecked car was discovered. I would like you to take me to see that car this morning.”

“All right. We’ll go now.”

Seated in the department’s truck beside the Fence Inspector, Bony said:

“Please proceed direct along the route taken by Loftus the night he disappeared.”

Bony was driven round the hotel into the main street, then eastward past the shops and the boardinghouse and the bank, on past the garage at the extremity of the town.

“Loftus should have taken this right-hand road, but despite Wallace’s objection kept straight on,” explained his companion, whose name was Gray.

“Ah! Has that garage been long vacant?”

“Yes, about a year. The garage on the other side of the railway does all the business now.”

Once past the garage and the wide, good road running up a long, low hill south, they abruptly left the town, the road becoming narrow when it began to wind through whipstick mallee and gimlet trees. Now and then to his left Bony could see the rampart of mullock excavated from the great pipeline trench, with the railway beyond it.

“By the way,” he said, smiling, “I understand that Mrs. Poole’s husband is a Water Rat. Precisely in what manner is such an epithet applicable to a woman’s husband?”

Inspector Gray chuckled.

“The men employed along the pipe line are called Water Rats because often they have to work deep in water when a pipe bursts.”

“Thank you. And what are the Snake Charmers?”

“They are the permanent-way men. Now that you are a Rabbit Department employee you are a Rabbitoh.”

It became Bony’s turn to chuckle.

“What are the road repairers called?”

“Well, not being a blasphemous man, I am unable to tell you.”

“Then I must invent names for them myself. Did you know George Loftus well?”

“Moderately well. He was never a friend of mine, although he has been here five years.”

“Tell me all you know about him, please. What he looked like, everything.”

The Fence Inspector hesitated, and Bony saw that he was weighing carefully the words he would use to a police officer when there would have been no hesitation had Bony been an ordinary acquaintance. Why men and women should be so reserved in the presence of members of the police, who were their paid and organized protectors, was a point in human psychology which baffled him. At last Gray said:

“I suppose Loftus would be about twelve stone in weight, and of medium height. He was a rather popular kind of man, a good cricketer for all his forty-one years, would always oblige with a song, and was a keen member of the local lodge. For the first three years he worked hard on his farm, but he slacked a bit this last year. He left most of the farm work to his man.”

“Did he drink much?”

“A little too much.”

“His wife on the farm, still?”

“Yes. She is a good-looking woman, and, I think, a good wife.”

“Any children?”

“No.”

“The farm hand? What kind of a man is he?”

“He’d be about thirty. A good man, too. Loftus was lucky in getting him. Mick Landon his name is. Born in Australia. Fairly well educated. Is the secretary of several local committees and is the M.C. at all our dances.”

“Do you know, or have you heard, what Mrs. Loftus intends doing if her husband cannot be found?”

“Well, my wife was talking to her the other day, and Mrs. Loftus told her she didn’t believe her husband dead and that she was going to run the farm with Landon’s help until he came back.”

“I suppose his strange disappearance has upset her?”

“Yes, but there is more anger than sorrow, I think. Of course, he might come back at any time. There’s old Jelly, now. He disappears three or four times every year, sometimes oftener, and no one knows where he goes or what he does.”

“Indeed! You interest me. A woman, perhaps?”

“Knowing Bob Jelly, I can think so. Here we are at the Fence.”

CHAPTER III

The Wheat Belt

A wide tubular and netted gate in a netted fence four feet nine inches high, and topped with barbed wire, halted further progress. Climbing from the truck, Bony made a swift survey of the surrounding country.

The Fence ran north and south in a straight line, to the summit of a northern rise and to the belt of big timber to the south. Elaborate precautions had been taken in its construction to keep it rabbitproof where it crossed the pipe line, whilst the single-track railway line passed over a sunken pit. The Fence gate had been repaired, but the wrecked car was still lying partly down on the massive pipe line. The half-caste paced the distance between Fence gate and car and found it to be little more than fourteen yards.

About five hundred yards beyond the Fence was a house belonging, he was informed, to the Rabbit Department farm, and then occupied by the farm foreman. Also beyond the Fence, and on the farther side of the railway, was a farmhouse occupied by a farmer named Judd.

Gray was disappointed when Bony failed to run about like a hunting dog, as all good detectives are supposed to do. For a detective he seemed too casual, and his blue eyes too dreamy. Yet Bony saw all that he wanted to see, which was that the backing of the car from gate to pipe line was done quite naturally, with no tree stumps near to make the act a matter of chance.

“I hate the word, but I must use it,” Bony said softly. “I am intrigued. Yes, that is the word I dislike. The railway crossed by the Rabbit Fence makes a perfect cross. On all four sides the land is cleared of timber and now is supporting ripe wheat. Here is difficult country in which to hide a human body indefinitely; for, supposing the remains of George Loftus were hidden somewhere among all those acres of waving wheat, it would be only a matter of time before a man driving a harvester machine came across them. Assuming that Loftus was killed, what object could his murderer have in hiding his body for only a few weeks, excepting, perhaps, to put as great a distance between himself and it before the body was discovered. And to carry the body weighing twelve stone to the nearest timber, which I judge to be not less than three quarters of a mile distant, would be no mean feat.”

“It’s mighty strange what’s become of him,” the Fence Inspector gave it as his opinion.

“I shall find him alive, if not dead.”

“You think so?”

“I am sure of it. My illustrious namesake was defeated but once—at Waterloo. I was defeated once . . . officially, at Windee Station, New South Wales. I shall not meet my Waterloo twice.”

Inspector Gray hid his face with cupped hands, which sheltered a cigarette-lighting match, to conceal his silent laughter. Bony proceeded, unaware of the effect his vanity was having on his companion. Pointing to the Fence, he said:

“I see several posts which want renewing. I suggest that you employ me cutting and carting posts and replacing those old ones. It will give me both opportunity to look about and time to study this affair. Now, please, take me on along the road Loftus would have taken from here to his house.”

Proceeding southward west of the Fence, the land to left and right appeared as a golden inland sea caressing the emerald shores of bush and timber. The drone of gigantic bees vibrated the shadowless world—the harvesting machines were at work stripping fifteen bushels of wheat from every acre.

Crossing the old York Road and then continuing straight south, the truck sped up a long, low grade of sandy land which bore thick bush of so different an aspect from that familiar to Bony in the eastern States that he was charmed by its freshness. Here this bush, by its possible concealment of the body of Loftus, presented a thousand difficulties: for in it an army corps could live unseen and unsuspected.

“What is your real opinion of this case?” Gray asked.

“Tell me your opinion first,” Bony countered.

Silence for fully a minute. Then:

“This is the twelfth day since Loftus disappeared. It is my firm belief that he didn’t just wander into the bush and perish. As you see, there is as much cleared land as uncleared bush. Loftus was not a new chum, and even a new chum hopelessly slewed would surely come to the edge of cleared land, where nine times in ten he would be able to see a farmhouse. I think he was killed for the money he might have had with him—anything from a shilling to a fiver—either where his car was found or at some point on his way home, possibly as he crossed the old York Road.”

“Muir informed me that the vicinity of the York Road gate, as well as the edges of the wheat paddocks around the wrecked car, was thoroughly searched.”

“Doubtless that is so,” Gray assented. “Still, the possibility remains that Loftus may have been killed by a man or men possessing a car, who could have taken the body miles away to hide it in uncleared bush north of the one-mile peg beyond the railway.”

“There is solidity in the composition of your theory,” Bony said slowly, his eyes half closed, yet aware of the quick look brought by his ponderous language. “I am beginning to think that tracing Loftus will resemble the proverbial looking for a needle in a haystack. However, we must not rule out the possibility that Loftus disappeared intentionally. How did he stand financially?”

“He was as sound as the average farmer.”

“And how sound is the average farmer—I mean in this district?”

“Distinctly rocky. Nearly all are in the hands of the Government Bank.”

“Was Loftus an—er—amorous man, do you think?”

Inspector Gray took time to answer this pertinent question.

“Well, no,” he replied deliberately. “I should not consider him amorous. To an extent he was popular with the ladies, but, nevertheless, he was a home bird. And, as I said before, Mrs. Loftus is still young, good-looking, and a good wife. There you see the Loftus farm.”