0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Passerino

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A landmark of the Harlem Renaissance, Cane is a haunting mosaic of prose, poetry, and drama that captures the struggles, beauty, and contradictions of African American life in the early twentieth century. Set against the backdrop of the rural South and the urban North, Toomer’s modernist masterpiece blends lyrical vignettes with unforgettable portraits of men and women navigating love, labor, race, and identity. Its experimental form and poetic intensity make it not only a groundbreaking work of its era, but also a timeless meditation on the human condition. Praised by critics from its first publication in 1923, Cane remains one of the most innovative and influential works in American literature. Readers are invited to enter a world where memory, song, and story converge to illuminate the soul of a people and a nation in transformation.

“One of the most beautiful and startling books in our literature.” — Alice Walker

Jean Toomer (1894–1967) was an American writer, poet, and playwright best known for Cane (1923), a groundbreaking work of the Harlem Renaissance. Born in Washington, D.C., Toomer was of mixed racial heritage and moved fluidly between Black and white communities, an experience that profoundly shaped his art. His writing blends modernist experimentation with themes of race, identity, and spirituality. Though Cane was his only major book of fiction, its influence endures as one of the most innovative and powerful works in American literature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Cane

The sky is the limit

Table of contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Part I

Karintha

Reapers

November Cotton Flower

Becky

Face

Cotton Song

Carma

Song of the Son

Georgia Dusk

Fern

Nullo

Evening Song

Esther

Conversion

Portrait in Georgia

Blood-Burning Moon

Part II

Seventh Street

Rhobert

Avey

Beehive

Storm Ending

Theater

Her Lips Are Copper Wire

Calling Jesus

Box Seat

Prayer

Harvest Song

Bona and Paul

Kabnis

landmarks

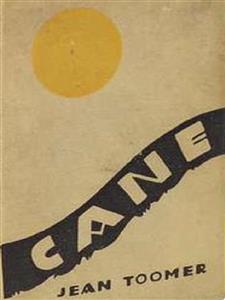

Title page

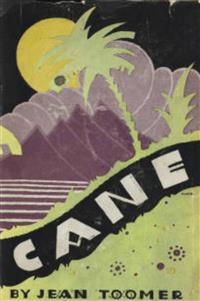

Cover

Table of contents

Book start

Dedication

To my grandmother …

Epigraph

Oracular.

Foreword

Reading this book, I had the vision of a land, heretofore sunk in the mists of muteness, suddenly rising up into the eminence of song. Innumerable books have been written about the South; some good books have been written in the South. This book is the South. I do not mean that Cane covers the South or is the South’s full voice. Merely this: a poet has arisen among our American youth who has known how to turn the essences and materials of his Southland into the essences and materials of literature. A poet has arisen in that land who writes, not as a Southerner, not as a rebel against Southerners, not as a Negro, not as apologist or priest or critic: who writes as a poet. The fashioning of beauty is ever foremost in his inspiration: not forcedly but simply, and because these ultimate aspects of his world are to him more real than all its specific problems. He has made songs and lovely stories of his land … not of its yesterday, but of its immediate life. And that has been enough.

Part I

Karintha

Her skin is like dusk on the eastern horizon,

Reapers

November Cotton Flower

Becky

Becky was the white woman who had two Negro sons. She’s dead; they’ve gone away. The pines whisper to Jesus. The Bible flaps its leaves with an aimless rustle on her mound.