Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Aniara

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Caroline

- Sprache: Englisch

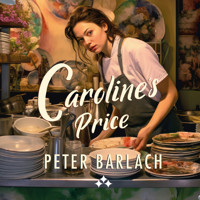

Caroline's tapas bar is thriving—until she rescues Zulfiya, an exploited cleaner trapped by ruthless traffickers. What begins as an act of kindness spirals into a dangerous game of cat and mouse with the Azerbaijani mafia. Between juggling a chaotic kitchen, navigating an ill-fated entanglement with a commitment-phobic detective, and keeping her found family safe, Caroline must decide how far she'll go to protect those she loves. But when threats escalate and violence strikes close to home, her signature defiance may have finally met its match.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 255

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CAROLINE’S PRICE

PETER BARLACH

Aniara, 2025

www.aniara.one

© Peter Barlach

Original title: Carolines pris

English translation by Aniara

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher or author, except as permitted by EU copyright law.

ISBN Print: 978-91-9007-590-6

ISBN E-book: 978-91-9007-533-3

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

CHAPTER1

“Caroline, I’m packing it in!” Viktor says behind my back. I step away from the booking station and turn round. He’s breathing heavily and his face is flushed, so I can tell something significant has happened to wind him up.

“What a shame – you’re my best waiter!” I realise I need time to sort this out, and nobody walks away mid-compliment.

“Yeah, well, I just can’t stay here any more. I have to go. Now.”

Long-term, him quitting isn’t a problem. People like working for me, and even though I meant what I said, he’s not irreplaceable. Short-term, it’s trickier. We open in an hour and I’ve just seen we’re nearly fully booked. We can always call in extra staff, but neither Bente nor I have time for that right now. Bringing up his three-month notice period wouldn’t be fair, especially not with someone who looks ready to burst into tears.

“Is it something I’ve done?”

“No, absolutely not, you’re the best boss I...”

“Because you’re really putting me in a spot here, you get that, right?”

“I’m sorry, but I can’t.”

“Just tell me one thing. Why?”

Viktor sighs deeply and stares at the floor. He runs his fingers through his blonde sideburns, making them stick up. I check my watch. Three fifty-seven. We open at five. I give myself three minutes to fix this, then I’ll have to find someone else.

Before he can explain himself, I ask him to look out across our beautiful, spacious restaurant which, since opening just a year ago, has become one of Stockholm’s biggest success stories.

“Viktor, in a few hours there’ll be ninety people here at The Cooler eating one of the best meals of their lives, and you’ll charm them all senseless and earn good money and even better tips, why would you want to–”

“There’s a fascist in the kitchen!”

“Is that right?” I think I’m starting to understand what’s happened. “Well then, let’s go and have a word with this fascist.”

“I’ve tried, but you can’t reason with their sort.”

“Yes, you can! Come on!” I take him by the arm and walk through the restaurant, past the bar towards the kitchen.

I explain that if he’s going to leave me in the lurch, this is the least he can do. I once watched a documentary about talking to suicide jumpers – if you take it one small step at a time, you’ve got a chance of success. Every second that passes without him jumping is a victory. I shouldn’t start by trying to drag him back over the railing – that might make him jump. The goal is to get him to climb back over to my side voluntarily.

At the swing door to the kitchen, we meet Bente struggling with a box.

“You’re not carrying anything too heavy, are you, sweetie?”

She rolls her doe eyes dramatically.

“They’re cashews, and I’m four months pregnant, Mum!”

“Right, fine, but we’ve got Mussolini in the kitchen – call pest control!” I shout as the door swings the other way.

“That’s not funny,” Viktor mutters.

“Sorry,” I say, realising it was a stupid, stupid thing to say. Not for the same reason as him, perhaps, but still.

We enter my perfect, just-the-right-size kitchen.

“Oh, you went running to the boss, how brave,” says Hillevi, tears in her voice as she stands at one of the three prep stations, slicing carrots.

Hillevi is by far my best cold-kitchen chef, so I’m relieved she’s not the one quitting. As long as she keeps baking heavenly sourdough baguettes and chopping vegetables at the speed of light, she can believe whatever she wants in her spare time.

“Viktor says you’re a fascist and now he wants to quit.”

“I’m not,” says Hillevi, continuing to chop.

“Sorry, my dear friends,” I say in the strongest, most boss-like voice I can muster whilst raising my arms. It works – they both look at me. “But my little brother died when I was thirteen and after that I used all my energy at school pretending I was fine and making sure no one noticed when I played truant, so I usually say I only did six years of basic schooling and I’m not exactly well-educated. What does that word fascist actually mean?”

“I wonder about that too,” says Hillevi.

“She despises the weak and wants to establish a nationalist, authoritarian state.”

“Did I say that?”

“I’m scared stiff of people like her,” Viktor says. “History’s repeating itself – she says she wants to close the border and throw out...”

“I’m just saying our lifeboat is full, we can’t help any more people!” Hillevi shouts.

“That’s exactly what Peter Mangs said too!”

“Who’s Peter Mangs?” I ask.

“Sweden’s worst serial killer. He only shot immigrants. Or ‘invaders’ as Hillevi and her disgusting friends call poor helpless people fleeing from war.”

“Stop talking like that...” Hillevi can’t hold back any more and lets the tears flow.

“There it is, cry me a river since you’re such a victim, for Christ’s sake!” Viktor snaps, and they keep bickering.

Hjalmar, my eternally cheerful head chef, emerges from the toilet in the corridor by the back door.

“Right then, I’ve dumped my ballast and I’m ready for the pass,” he announces, pulling on his nitrile gloves.

I explain what’s happened, and he tells me they’ve been squabbling on and off since they started, and that he’s really tried to lighten the mood.

“I’m sorry, Caroline, it’s my responsibility to make sure there’s no fighting in the kitchen.”

“No, I’m the one who hired them.”

“Listen, kids,” says Hjalmar, taking a couple of steps forward. “Discussing politics in a restaurant kitchen is like talking about porn in a parish hall – some things you just don’t do.”

They ignore him.

“Come on, now,” he continues, “all you need in a kitchen is a good mood and sharp knives!”

“I teach Swedish to two Syrians in my spare time, what are you doing to make the world a better place?” Viktor says to Hillevi.

“Screw you, virtue signalling like you’re the messiah!”

He raises his pale tattooed arm at her, and she looks so angry her yellow-dyed hair resembles a wildfire.

“We live in one of the richest countries in the world and people like you...”

“Lived,” Hillevi shouts. “It’s all going to hell, I’m actually sick-to-my-stomach scared that it’s going to...”

I raise my voice and say it’s my turn. I explain that they’re not employed for their opinions and that in this restaurant we have freedom of expression just like in the rest of Sweden.

“And I don’t want to be intolerant of anyone, not even the intolerant, but if you have a problem with this, Viktor, I understand and respect that. And I’ll take your apron right now and you can leave immediately – I won’t argue about notice periods. But before you go, I want to point something out to both of you. There was one adjective I heard you both use. Do you know which one?”

They stare at me blankly.

“Scared. You both said you were scared. That hit me harder than all the other arguments put together. Hit me right in the gut. Because ‘scared’ is an adjective, right? That’s what they taught us in middle school, isn’t it?”

They nod.

“You sound like a public service broadcaster – like it’s all about balance and impartiality” says Hillevi.

But I’m not backing down, and without having to turn around I know Bente has entered the kitchen.

“You’re calling each other nasty names, slapping labels on each other. Bente, you’ve got a husband and kids – isn’t rule number one in a family that you don’t do that?”

“Yeah, I called Danilo an idiot this morning; ended up having to apologise even though he was the one being thick.”

Viktor smooths down his blond sideburns this time – maybe that’s a good sign?

“Caroline, we just got a booking for eight people,” Bente continues.

“I thought we were full,” I say, though I know she’s lying.

“Regulars. You know how it is.”

“I know,” I say, nodding to Bente as she leaves the kitchen. “Please, everyone, we need to work now. And Viktor. Just take a break from all this. Hillevi won’t become more of a fascist just because she’s chopping parsley for the gremolata you’re serving, and Hillevi, Viktor won’t become more of a traitor to his country just because my guests order food from him. Can we just call a truce? We’re so full tonight that even if the king and queen wanted to eat here, we’d have to turn them away.”

I turn to Viktor. Time to talk him back over the rail once and for all.

“Listen, my star waiter,” I say in my softest voice. “How about helping me break some records tonight?”

“Fine, I’ll stay then,” Viktor mutters. “For YOUR sake, Caroline.”

They both seem a little ashamed, but order is restored and everyone can get back to their stations.

I head out to where Bente is placing the “Please Step Outside to Use Your Phone” signs on the tables. They’re left over from my first restaurant, Caroline’s Tapas, and I’ll keep using them as long as I run this place.

You can tell she’s moving more slowly, and it’s clearly visible that she’s pregnant. Bente is well over forty and got pregnant “at the eleventh hour” as she puts it. She’s my business partner and best friend. I got to know her and her autistic son Hannes when I was hanging around the Eriksdal Leisure Centre. That was only five years ago, but feels like a hundred. Or like yesterday.

“You handled that conflict brilliantly, sweetie,” Bente says when she sees me.

“Thanks, I did work experience as UN Secretary-General in eighth grade,” I say.

“You never told me that!”

“There’s a lot I haven’t told you,” I say.

“And there’s so much I’d rather not know,” says Bente with a light laugh.

CHAPTER2

“You know what poor man’s hollandaise is, Caroline?” asks Vladan, a successful film director and regular at The Cooler.

“No,” I reply.

“Tube mayo and Tabasco,” he says, letting out a hearty laugh.

He’s here with his gorgeous girlfriend Sally, and he loves telling both of us how skint he used to be. Apparently, he was a “failed artist” all his life until now. These days he makes films all over the world and is “as rich as I’m ugly.”

“I mostly lived on macaroni and tomato sauce, but sometimes I’d celebrate with fish fingers and poor man’s hollandaise,” he continues.

“Bet you didn’t get girls as pretty as me back then,” Sally drawls in her northern lilt.

“Not even close,” says Vladan, studying the wine list.

“Caroline, you do realise I’m only with him for his money?”

“And I’m only with you for your looks,” Vladan says with a satisfied smile.

That’s their manner with each other. Rough around the edges, but sweet at heart.

“And we’ll celebrate that with a bottle of Clos du Val D’Eleon, 2009,” Vladan says with perfect French pronunciation. “Will it work with the scallops?”

“If I ask Hjalmar to go easy on the chilli, it should be perfect.”

Vladan and Sally come here as often as they can. It’s always fun talking to them. He’s somewhere between forty and fifty, and she’s about twenty-five, with high cheekbones and ocean-blue eyes that could make anyone want to run naked through a summer meadow. He has dark brown eyes and a nose that makes you understand why ‘beak’ became slang for nose.

If I ever end up in a relationship, I want it to be like Vladan and Sally’s.

I thank them and glide on.

It’s a brilliant night at The Cooler. Nearly full house, which means close to ninety guests times two sittings. There’s a great flow and a lovely buzz. Both front of house and kitchen are working their arses off.

Viktor seems to have completely forgotten about the kitchen quarrel as he glides around glowing, putting all the guests in a good mood. Tonight I even have time to play the friendly restaurant owner. I move between tables chatting with guests, and when the moment’s right, I add the final touches to the dishes.

Spring has arrived in Stockholm and our tiny outdoor terrace is packed.

Things are finally falling into place in my life. That question I’ve been asked a million times – “Will you ever learn, Caroline?” – has started getting a new answer: “Yes, I will.”

Eight months in Swedish prison made me into a new person. Not just because I changed my surname from Mum’s Södergren to Dad’s Holst, but because, deep down, I had time to examine myself. You don’t have to become a dull and grey person just because you develop a bit of impulse control.

I’m starting to get along with the new Caroline. New Caroline doesn’t smoke, drinks in moderation, exercises regularly and asks for advice before making big decisions. New Caroline only picks low-hanging fruit. New Caroline even does weight training!

But still. Something gnaws and stings inside me, and I don’t know what it is. A constant low-grade feeling of anxiety, a knot in my stomach that I don’t like.

When I was younger, I was often alone but never felt lonely. These days it’s the opposite. I’m surrounded by people almost constantly, but I feel lonely. When I look at all the couples who come here – and there are many – I get jealous. I seem capable of creating a romantic atmosphere, but I don’t get to be part of it myself. Outside it’s spring, but down in my gut it’s autumn, or whatever you’d call it.

Maybe it’s just sex I’m missing? I haven’t slept with anyone since my affair with my former solicitor, Oscar. I thought I was in love, but I probably just mixed up the two Hs – horny and head over heels. The moment lust was supposed to slide into love, I lost interest. Am I afraid of love? Or is it just meant for certain people?

There’s this handsome guy who dines here several nights a week. His name is Pål and he has a shaved head, warm eyes, and a straight, fine nose. He had the power to make my knees buckle – right until I asked what he did for a living.

“I’m a copper,” he answered, killing our little flirtation.

When Bente told me she was pregnant by Danilo, her boyfriend ten years her junior, I cried tears of joy. After she left, I kept crying, but they weren’t tears of joy running down my cheek any more. Even though there isn’t anyone in the whole world I’d wish a child for more than Bente, it hurts. Maybe it’s jealousy too, since Hannes gets along so well with Danilo. I like Danilo too, a charmer from Croatia who’s kind through and through. Perfect for Bente, but Hannes isn’t here as often any more, and Bente has stopped sharing all the cute things he says. When I see him, we have a wonderful time and I can tell he’s doing better than ever, yet something still bugs me. Is it that I want a child of my own? I don’t know, I just know that as soon as I’m not working, I don’t feel good. Is that how life should be?

Is this when I start paying for my chaotic childhood with an alcoholic father, a disabled brother, and an absent mother? Or am I feeling low because I never smoke or do drugs, rarely get drunk, and have stopped sleeping around? Maybe I need a dash of healthy self-destruction to spice up my life.

With my therapist Bo, I’ve discussed intimacy issues, a concept I read about somewhere. I told him that “some people are messed up in the head, but I feel completely messed up in my crotch.” We both laughed because we share a sense of humour, but the both of us also think there might be something to it. Anyway, I’m trying to think less and work more.

Tonight Siv and Petter from Töreboda, a small town in western Sweden, are here. They always brighten up the place. Not just because their West Swedish accent is so charming, but because they radiate kindness and love. You couldn’t find people more wonderfully rustic, and I love it. They’ve told me they’ve sold their house, moved to a flat, and now devote their lives to travelling around Sweden listening to music. They love folk songs, and apparently tonight they’re off to hear two male troubadours called Erik and Bruno, who are supposedly “fantastic.”

“Have you heard of them?” Siv asks.

“No, though you could probably rattle off a thousand male Swedish folk singers and I wouldn’t know any of them.”

“Won’t you join us tonight then?” Siv says. “You look like you could use some time off.”

“That would be lovely, but unfortunately I have to work,” I lie, since I’d rather stick my hands in the deep fryer than listen to two blokes with guitars. But I love Siv and Petter for making it their Saturday night out. Every time they’re in Stockholm, they eat at The Cooler. They’d read some long article about me in a magazine and thought I seemed “so delightful.” I’ve deliberately avoided reading a single word about myself in any paper or looking at any pictures.

Vladan and Sally praise our seared scallops with shiitake mushrooms, silken lime butter, and avocado salad. Hjalmar deserves the credit, but I accept their compliments.

They’re sitting in the “Bird’s Nook”, my favourite spot at The Cooler. It’s half a flight up and the cosiest, most secluded part of the restaurant – though it feels like a small booth, you can still survey everything from there. The green cockatoo lamps that Bente bought for the launch of Caroline’s Tapas adorn the walls.

“Don’t you ever want to settle down, Caroline?” Vladan asks, after ordering a second bottle of wine.

Before I can answer, Sally calls out: “Just so you know, old man, I haven’t settled down either.”

“Yeah, yeah,” he mutters.

There’s something reassuring about Vladan and Sally – no matter how drunk they get, their bickering never goes beyond this.

“Caroline’s like me,” Sally continues, taking my arm. “Volatile. Do you know what that means?”

“Nope.”

“Changeable. From volare which means ‘to fly’ in Italian. Do you know Italian?”

“Nope. Well, yes. I know the word for ‘cooking time’.”

They look at me questioningly.

“Cottura,” I say. “It’s written on pasta packets.”

They laugh, so I continue: “I can count to ten too, which means I can travel around Italy discussing cooking times. Unless it’s thick pasta that needs to cook for more than ten minutes.”

I leave them to check on the kitchen.

“Volatile”. Now there’s a posh word. Maybe that’s what I am. Changeable. Sounds better than having intimacy issues, at least.

CHAPTER3

It’s always a joy to watch Hjalmar work. The more he has to do, the happier he gets.

His predecessors were deadbeats from the Jobcentre. Looked reliable on paper, but in reality, I’d sooner have hired my mother.

Hjalmar had been the star attraction at several top restaurants in town, but he’d had enough of that. He’s over fifty and wants to work in a kitchen. He got tired of what I spend most evenings doing – making conversation.

Before I hired him – with a profit-sharing scheme to make sure he wouldn’t suddenly quit – I was about to drown in stress. I remember once when I was making meringue and had forgotten whether to use the yolk or the white. And I’d get furious with tables ordering their meat at different levels of doneness.

I don’t know how he does it, but Hjalmar can juggle fifty dishes in his head at once. Knows exactly what order everything needs to be done in. If we were cooking for each other, we’d probably both agree my food tastes better. But if we’re cooking for eighty people, he wins hands down. Hjalmar can tell precisely when a steak is perfectly medium rare, even from three metres away. He can be completely absorbed in plating papaya-marinated pork collar with roasted root vegetables when you hear him call out: “Ava, flip that Arctic char, would you!”

Besides, like me, he hates wasting food. During his job interview, I asked what he thought of people who throw out milk that’s past its best-before date without even sniffing it first.

He stared at me for a long moment before answering in a grave voice: “People who throw out milk without even smelling it first should be sent back to live on an eighteenth-century Swedish farm for three lifetimes to learn their lesson. Then – and only then – can they return to the welfare state.”

We shook hands and just like that, he was hired.

Hjalmar and I always discuss the menu and what’s going to be the main ingredient in Tonight’s Special. It’s like he’s got the entire restaurant’s inventory stored in his head and knows exactly what needs using.

The Cooler is open from 5 pm to midnight every day except Mondays, and I love that I get customers from all walks of life. Just like in the real cooler. There you’d find everyone from IT directors who’d spotted a biscuit tin they couldn’t keep their hands out of, to the hairdresser from up north who started dealing “wacky baccy” to supplement her salon wages. Bente and I worked out a careful plan for my release and our new business venture. She managed to multiply our initial capital of 750,000 kronor through some clever property deals, and I agreed to do as many interviews as she thought necessary when we opened The Cooler.

I’ve lost count of how many journalists I told the story to – about how and why I mercy-killed my friend and neighbour, Nancy Urdin, when she was somewhere between ninety and death. In interview after interview, I explained how I got caught and how, in prison, I came up with the concept for The Cooler. It was actually Bente and me together, but Bente, who knows her marketing, explained that the media wants a star. And I’m that star.

It worked. Seems like everyone in this city knows about The Cooler.

“Storytelling,” Bente said. “Marketing’s greatest power. Have a story to tell whilst you’re launching a new brand.” She explained it so many times that even I got it. “Then once you’re famous, all it takes is celebrity chef Caroline opening a new venture and the press comes running.”

When I was in prison, each block was responsible for its own food, and I had just 42 kronor per person per day to cook with, so I learned to pull rabbits out of hats. I brought that concept to The Cooler, where every day we offer a set menu of two slow-cooked stews – one vegetarian and one meat or fish – and diners can choose their own sides. I break even on these stews, but of course we have an à la carte menu as well and with alcohol, we turn a clear profit. We also have different themes depending on the season and what’s available.

We do everything from octopus to steak tartare nights. Naturally, we have tapas evenings and several signature dishes. As long as I’m running this place, Caroline’s Bloody Mary gazpacho and escargot bruschetta will stay on the menu. The most fun is probably Caroline’s Experiment. We don’t always have it, but when I’m testing something new or mess something up, we push it as Caroline’s Experiment. If it’s not good, you get your money back. It usually sells out, and so far, no one’s complained.

Tonight the stews consist of an ossobuco and a lentil and cauliflower stew. As always, the trick is the stock. When I make my ossobuco, or rather when Hjalmar makes my ossobuco, it’s initially cooked once in the traditional way. Seared veal shank with onion, garlic, parsley, bay leaves, carrots, celeriac, parsnip, crushed tomatoes and white wine simmers for about two hours and fifteen minutes. That’s when the conventional stew would be done. But not mine, because after that you set aside the shank, strain off the vegetables and seasonings, and reduce the liquid until only a tenth remains. Then you serve it with the shank, freshly grilled root vegetables and pressed potatoes. The stew becomes darker, deeper and richer. I used to feel anxious about wasting the first round of vegetables, which can’t be served or reused, but now Jonas, who I buy wild boar from, and I have arranged it so that all my waste becomes feed that he uses to lure the wild boars that I then buy from him.

Ultra-ecological recycling. As a garnish, I stick with classic gremolata. Lemon, parsley, and garlic are perfect as they are. Trying to improve on the original would be like a mechanic trying to invent a rounder wheel.

The clock’s pushing eleven, we’re out of ossobuco, and the dining room’s starting to thin out.

“Caroline, can we pay?” Vladan calls from the Bird’s Nook.

I give them a thumbs-up and signal Viktor to handle it.

Meanwhile, I head into the kitchen where Hjalmar is now prepping tomorrow’s stews with Hillevi and the prep cooks Ava and Julia.

Someone’s spilled rapeseed oil on the floor, so to prevent anyone from slipping I scatter a bowl of salt over it to soak up the oil.

The absolute best thing about having expanded and become successful is that we can outsource all the cleaning. There’s this nice dog owner from Azerbaijan whose cleaning company takes care of everything. Ilham’s Cleaning. It works perfectly – the whole place, including the changing rooms, is spotless when we start in the morning.

There’s a new woman here today. She’s going around spraying all the work surfaces.

“Hi, do you speak Swedish?” I ask, as I usually do.

“No,” she says, shaking her head nervously.

“English?”

“A little,” she answers with a heavy accent.

I can tell she’s unsure, so I flash my widest smile and walk over to her with my hand extended.

“Hello, I’m Caroline.”

She turns off the tap, takes off her glove, and slowly extends her hand.

“Zulfiya.”

“Where are you from?”

“Uzbekistan.”

“Right,” I say, watching a world map flutter through my mind, without managing to pin down Uzbekistan.

“For how long have you been in Sweden?”

She eyes me suspiciously.

“Two months.”

“Do you like it here?”

I can tell from her face that the question is daft.

“Yes...”

When I smile and tell her she can come to me if she has any questions, she just smiles back blankly.

There are so many unhappy people in this world, and I should be so grateful I’m not one of them. My brooding is ridiculous. With a brush, I sweep up the salt that has now soaked up the oil, so no one risks slipping on my floor.

CHAPTER4

The clock radio blares at 5:50. The same old-fashioned wail it’s had since I bought it as a housewarming gift to myself ten years ago. My hand moves automatically to the off button and I’m up straight away. I haven’t had snooze privileges in years. I’ve laid out my workout clothes and packed my light running rucksack with things I need to take to work, plus a towel.

My Persian friend Mernosh waits for me in the entrance at six sharp for our weekly run. With any luck, we’ll squeeze in a lesson at her self-defence class too.

Mernosh is the solicitor who took over when my first barrister fell in love with me and couldn’t handle my case – the one about my mercy killing of Nancy Urdin. Mernosh made sure I only got one year for manslaughter and was out after eight months.

Prison did me good in many ways. Without it, I wouldn’t have started working out, for instance. It began with brisk walks, and after a few months it felt completely natural to start running, and then I noticed I just kept running faster and faster, further and further. So I tried the one thing I’d sworn I’d never do: going to the gym. Another inmate called Selma, who I looked after in there, and I started lifting weights and motivating each other. Unfortunately she escaped on St. Lucia’s Day, but I stayed and kept training.