11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

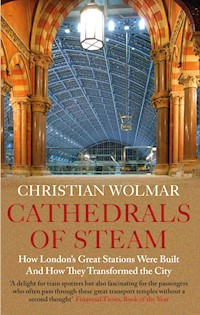

'Fascinating' 'Books of the Year', Financial Times 'London's twelve great rail termini are the epic survivors of the Victorian age... Wolmar brings them to life with the knowledge of an expert and the panache of a connoisseur.'Simon Jenkins 'A wonderful tour, full of vivid incident and surprising detail.' Simon Bradley London hosts twelve major railway stations, more than any other city in the world. They range from the grand and palatial, such as King's Cross and Paddington, to the modest and lesser known, such as Fenchurch Street and Cannon Street. These monuments to the age of the train are the hub of London's transport system and their development, decline and recent renewal have determined the history of the capital in many ways. Built between 1836 and 1899 by competing private train companies seeking to outdo one another, the construction of these terminuses caused tremendous upheaval and had a widespread impact on their local surroundings. What were once called 'slums' were demolished, green spaces and cemeteries were concreted over, and vast marshalling yards, engine sheds and carriage depots sprung up in their place. In a compelling and dramatic narrative, Christian Wolmar traces the development of these magnificent cathedrals of steam, provides unique insights into their history, with many entertaining anecdotes, and celebrates the recent transformation of several of these stations into wonderful blends of the old and the new.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

By the same author

Railways

A Short History of Trains

Driverless Cars: On a Road to Nowhere

The Story of Crossrail

Railways & the Raj

Are Trams Socialist?

To the Edge of the World

Engines of War

Blood, Iron & Gold

Fire & Steam

The Subterranean Railway

On the Wrong Line

Down the Tube Broken Rails

Forgotten Children

Stagecoach

The Great Railway Disaster

The Great Railway Revolution

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christian Wolmar, 2020

The moral right of Christian Wolmar to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-920-2

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-921-9

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-922-6

Map artwork by Jeff Edwards

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Dedicated to my wife, Deborah Maby, with whom I was in lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic for nearly the whole period of writing this book, and who put up with me dodging the housework. Also to Sir John Betjeman, whose writing I sadly cannot match, but whose enthusiasm I can.

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Maps

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. Starting slowly

2. The railway in the sky

3. The first cathedrals

4. A modicum of order

5. Breaching the City walls

6. Upstaging King’s Cross – or not?

7. Southern invasion

8. The three sisters

9. The workers’ station

10. A terminus too far

11. London’s unique dozen

12. Settling down and dodging the bombs

13. Round London with Sir John Betjeman

Appendix I: Timeline for the opening of London’s terminus stations

Appendix II: Passenger numbers in the year to 31 March 2019 at the London terminuses

Select Bibliography

References

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

SECTION ONE

1. Part of the London & Greenwich Railway, which opened in 1836. Line engraving by A.R. Grieve. (SSPL/Getty Images)

2. Spa Road railway station by Robert Blemmell Schnebbelie, 1836. (The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

3. The London terminus of the Brighton and Dover Railroads, 1844. Colour engraving by H. Adlard after an original drawing by J. Marchant. (SSPL/Getty Images)

4. Camden Town Engine House, London, July 1838. Coloured lithograph drawn by J.C. Bourne. (SSPL/Getty Images)

5. Primrose Hill tunnel, 10 October 1837. Wash drawing by J.C. Bourne. (SSPL/Getty Images)

6. Nine Elms station, London, 1838–1848. (SSPL/Getty Images)

7. Bishopsgate station, 1862. (Bridgeman Images)

8. Cannon Street railway bridge leading to Cannon Street station, c.1880. (Sean Sexton/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

9. King’s Cross station, c.1860. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

10. Illustration of the dust heaps in Somers Town. (The Print Collector via Getty Images)

11. Erection of the roof of St Pancras station, 1868. (SSPL/Getty Images)

12. Construction of St Pancras station cellars, 2 July 1867. (SSPL/Getty Images)

13. The Midland Grand Hotel and St Pancras station, c.1880. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

14. Midland Railways Milk & Fish Depot, c.1894. (SSPL/Getty Images)

15. The Doric arch at the entrance to Euston station, 7 September 1904. (SSPL/Getty Images)

16. The Great Hall at Euston station. (History and Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

SECTION TWO

1. Liverpool Street station, c.1885. (Paul Popper/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images)

2. Paddington station, c.1900. (Paul Popper/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images)

3. Broad Street station, 1898. (SSPL/Getty Images)

4. Fenchurch Street station, 1912. (English Heritage/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

5. Necropolis station, Westminster Bridge Road, c.1900. (The Print Collector/Getty Images)

6. Victory Arch, Waterloo station, 21 March 1922. (SSPL/Getty Images) 7. Crowds in Waterloo station heading off to Ascot. (William Gordon Davis/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/via Getty Images)

8. London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) poster showing the dining room of the Great Eastern Hotel at Liverpool Street station. Artwork by Gordon Nicoll. (SSPL/Getty Images)

9. ‘The Gate of Goodbye’, F.J. Mortimer, 1917. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

10. Victoria station, c.1950. (Central Press/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

11. Marylebone station, c.1950. (Allan Cash Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo)

12. Euston station main concourse, 2019. (Willy Barton/Shutterstock.com)

13. Interior of London Bridge station, 2019. (TK Kurikawa/Shutterstock.com)

14. View across Regent’s Canal towards Granary Square, 2019. (Sam Mellish/In Pictures via Getty Images Images)

15. Interior of King’s Cross station, 2018. (Jeff Whyte/Shutterstock.com)

16. Statue of Sir John Betjeman at St Pancras station. (cowardlion/Shutterstock.com)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

IAM GRATEFUL to my fellow cricketer Martin Matthews who suggested the idea for this book while we were chatting between overs a couple of years ago. Thanks are due to Simon Carne and Bernard Gambrill who both read the manuscript and made useful suggestions, Michael Holden for supplying a jigsaw of Waterloo station to help me through the lockdown, Joe Brown for providing figures on London’s rail mileage, Liam Browne for helping me on the station tour, and Rupert Brennan Brown as ever. Special mention must be made of Chris Randall, who went through the manuscript with a sub editor’s eye for detail as well as making numerous structural suggestions. Toby Mundy is my supportive agent and James Nightingale my patient editor at Atlantic Books for whom this is my eighth book. The errors, of course, are all mine.

I decided on using ‘terminuses’ rather than ‘termini’. There seems no good reason to use Latin plurals for a technology that the Romans, despite their fantastic ingenuity, did not develop.

INTRODUCTION

STATIONS WERE AN afterthought when the first railways were built. The Stockton & Darlington, a pioneering but technologically primitive railway, had no stations at all when its first trains ran in 1825. The Liverpool & Manchester, which opened five years later as the first intercity modern railway, did a little better, with huts at either end. Initially, stations on the early railways were crude affairs, little more than a path between tracks to enable passengers to clamber aboard and possibly a ticket office that might be located in the local pub.

By the time the railways reached London in 1836, six years after the completion of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, providing facilities for passengers was still seen by the railway companies as an irritating necessity rather than as a way of encouraging greater use.

The first terminus, London Bridge, opened in December 1836, provided little for its early passengers and had no architectural merit, but Euston, completed the following year, was a far grander affair as befitted the capital’s first main-line station. It was not so much that the passengers were offered any facilities to help them on their way but, rather, the railway company, the London & Birmingham, decided to erect a huge Doric arch in front of the station that served no purpose other than to demonstrate the importance of the company and of this new technology.

Things did begin to improve. The railway companies started to realize that passengers wanted a bit more than a ‘platform’ to access the trains, such as waiting rooms, toilets, newsagents, porters, ticket offices and easy connections to onward transport. The opening of these two stations triggered a quite remarkable period of station construction, which over the space of a mere four decades provided London with more than a dozen terminuses, nearly all of which, as this book describes, survive today. Only one, Marylebone, was built after 1874, and that was one of the most modest. It is a bigger collection of major terminus stations than has been built in any other city of the world and the process of the development and construction of these stations created the London of today. Vast swathes of housing and other older buildings, even churches and schools, were swept away in the railway companies’ rush to create this new form of transport that, in turn, caused further upheaval.

The companies were rapacious land grabbers whose rivalry was responsible for the establishment of such a large number of stations, but they had one aim in common: they wanted to get as near the centre of the capital as possible. Several companies started with stations that were further out and found that this severely constrained their ability to attract passengers. The reason why the stations ended up as a ring around the centre, nearly all connected by the Underground’s Circle Line, is a key part of this story. There are other Londons that can be imagined – one, for example, with a huge central station somewhere in the heart of the city, or another where there are fewer but better coordinated stations. However, as the book shows, competition rather than cooperation was the zeitgeist and explains London’s exceptionalism. Other cities, like Paris, had numerous terminus stations but there was more order and planning in the process of their development. In London, it was the whim of the railway companies, moderated only by the light touch of Parliament, that resulted in the pattern of the capital’s railways.

Each of these stations, even the smaller ones such as Fenchurch Street, required not only, obviously, a set of tracks leading into them, which caused further disruption to the existing built environment above and beyond their construction, but also quickly spawned other development, such as goods depots, warehouses, depositories and road access. All these stations were, as we would call them today, megaprojects, massive disruptive forces whose impact stretched well beyond their boundaries.

London was already on its way to becoming the world’s largest city when the railways first arrived in the 1830s and by the end of the nineteenth century was far larger and more affluent than any other in the world. The growth of the railways and of the city was a symbiotic process that academics have been unable to disentangle. All that can be said conclusively is that one would not have happened without the other.

These stations are all buildings in two parts, a fantastic blend of architecture and engineering that at times overlap. The façades, which consist mainly of hotels and offices, are the work of architects, or sometimes just the railway company manager who was blessed with a few design skills. Even though railways were a new technology, indeed a revolutionary one that had an impact on the way of life for everyone in the country, the architecture was mostly backward-looking. The styles harked back to the classical Greek and Roman eras, to medieval Gothic, to the Renaissance, with the Italianate style predominating, but never looked to the future, never celebrated the modern world that the railways themselves were creating. As the introduction to an exhibition of station architecture held in Paris in the late 1970s suggests, ‘In order to disguise the upheavals of the introduction of the railway into the town, the quasi-totalities of nineteenth-century station buildings take on the appearances of Greek temples, and Roman baths, Romanesque basilicas and Gothic cathedrals, Renaissance chateaux and Baroque abbeys’.1 Behind the facades, vast engine sheds were erected, often representing leading-edge technology of the era. It was all great fun for the railway companies, but less so for the passengers as none of these styles particularly suited the functioning of the railways.

We should, though, not complain, especially since, as I set out in the final chapter, nearly all the stations have been improved since the doldrums of the 1960s, when Euston’s arch and its Great Hall were demolished and other stations such as St Pancras and Charing Cross might have gone the same way. Instead, by and large – with the odd exception – London’s terminuses have been greatly enhanced, even much unloved London Bridge, by refurbishments and additions, most notably the new side entrance to King’s Cross.

This has been a happy book to write, a positive story for these hard times and one that John Betjeman, who features strongly in the last chapter, would greatly appreciate. The prospects for the future have only been darkened by the coronavirus pandemic sweeping through the country as I write. The effect on the railways has been devastating, with the government and the railway companies urging people not to use the railways, which until then had enjoyed more than two decades of almost uninterrupted growth, reaching record passenger numbers. The long-term impact remains to be seen as some passengers may not return to train travel, either because they have discovered that they can work from home, or because they are concerned about the risk of viral transmission. The terminus stations, while still functioning, are desolate places, bereft of the lively hustle and bustle that demonstrates their vitality and with their shops and cafés shuttered. Oddly, that made it a good time for me to study their architecture and design, and I am confident that they will regain their joie de vivre in the fullness of time.

Christian Wolmar

July 2020

ONE

STARTING SLOWLY

THE RAILWAYS CAME late to London, half a dozen years after the opening of the pioneering Liverpool & Manchester in 1830, but they quickly made up for lost time. Railways soon spread all around the capital and were a vital component of the rapid growth that turned London into the world’s first megacity. London not only acquired the world’s first underground railway network, beating all other cities across the globe by almost forty years, but also can boast today of having 598 railway stations and 756 route miles of line,1 and, most notably, more terminus stations than any other city in the world.

Those magnificent ‘cathedrals of steam’, built between 1836 and the end of the nineteenth century, have shaped London in many ways, creating new districts and destroying old ones, and influencing the type and location of housing and other developments across the capital. They, in turn, were built and located for reasons that can be understood only by considering the history and geography of the Thames basin in which London grew from a small Roman settlement established in the first century ad around where Vauxhall Bridge stands today. The Thames, and in particular its meandering arcs, have caused trouble ever since to London’s transport system, and the railways are no exception. Almost uniquely, too, of the British railway system, there was an element of planning and forethought about the location of the terminus stations that explains their location dotted along a ring around the West End and the City.

It is impossible to untangle the symbiotic relationship between the railway and the growth of the capital. In 1831, London’s population of 1.7 million was squeezed into an area of just eighteen square miles. It was already on the way to being the world’s biggest city and an incredibly cramped one. At the time, Hammersmith was known for its strawberries and orchards, and market gardens flourished on the gravel terraces west of Chelsea and up the Lea Valley. On the clay lands, large fields provided grain for people and hay for horses, while well laid out parks extended from the numerous country houses. Today, London, with its thirty-two boroughs and City Corporations, is thirty-four times larger at 618 square miles, whereas the population, at 8.8 million, has only grown by a factor of five. While undoubtedly the motor car has fuelled that expansion and allowed a reduction in density to take place, the process was started and developed in earnest by the existence of the railways, including the Underground and, later, trams.

Much of London before the advent of the railways was little changed from its Georgian heyday. It was still a dark place. Gas light was first used in London on Westminster Bridge in 1813 but spread only slowly until the mid-1820s, with most streets still being illuminated by infrequent oil lamps and pedestrians having to be escorted home by ‘link-boys’ bearing lights. According to Peter Ackroyd, ‘the outskirts retained a rural aspect… The great public buildings, with which the seat of empire was soon to be decorated, had not yet arisen. The characteristic entertainments were those of the late eighteenth century, too, with the dogfights, the cockfights, the pillory and the public executions.’2

However, changes were afoot. The area now encompassed by central London at the dawn of the railway age was booming, with massive developments on the great estates as some of their aristocratic owners realized that they were sitting on invaluable assets. London had undergone rapid transformation in the previous half century, particularly in the prosperous period in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars.

Whereas John Nash had been the principal architect of swathes of London during the late Georgian and Regency periods, such as Regent Street and the various terraces around Regent’s Park, the mantle had passed to Thomas Cubitt who was responsible for even more notable developments. After creating much of modern-day Bloomsbury, including Tavistock and Russell squares on land owned by the Duke of Bedford, Cubitt turned his attention to the Grosvenor Estate south of Hyde Park where he established both Belgravia and Pimlico on land that had previously been used as market gardens.

In his book A Short History of London, Simon Jenkins applauds these developments, suggesting that they were built to far higher standards than Nash’s terraces and that even today ‘their creamy cliffs of stucco… symbolize upmarket living to rich expatriates the world over’.3 There were other equally successful developments during the first three decades of the nineteenth century, including on the fields owned by the Bishop of London in Paddington and Bayswater; but a speculative scheme further west just beyond Notting Hill, supported by the owners, the Ladbroke family, proved a step too far and the rather grand terraces were soon sublet to poor families described by The Times as ‘a more filthy and disgusting crew we have seldom had the misfortune to encounter’.4 The pleasant squares built up by the large landowners remained interspersed with areas of slum housing, much of which would be cleared for railway development during the course of the century.

It is important to note that the outward suburban spread, which the railways would do much to stimulate, had already begun. To the north, St John’s Wood, Camden Town and Islington had grown up with sizeable housing suitable for the burgeoning middle classes. Further north, there was ribbon development of housing through Tottenham to Upper Edmonton, although away from the main road there were only fields and marshland. On the south bank of the Thames, there was continuous building between Rotherhithe and Lambeth, most of which were festering slums. Further south, however, there were more salubrious areas up to the New Kent Road and stretching out to Kennington and Walworth but nothing much beyond apart from villages.

In the west, beyond the elegant new squares, Chelsea remained a discrete village and along the Thames the Millbank slums were a terrible eyesore. The villages of Kensington, Hammersmith and Turnham Green, although linked to London by ribbon development, were not yet really part of the capital. Park Lane and the first section of the Edgware Road marked the north-west limit of London as Kilburn and Edgware were distant villages separated from the capital by large strips of agricultural land; the old Roman road itself was little more than a lane among the farms and fields.

In the east, thanks to intense activity in the Docklands, houses were replacing the fields in Bethnal Green. A few affluent master mariners and boat owners lived in the neat villas of Wapping and Shadwell but again there was considerable open space.

While for the most part the environs of London were sparsely populated and the various villages still small, with all this building activity London was well on the way to overtaking Peking (now Beijing) to become the largest city in the world. Its growth coincided perfectly with the advent of the railways.

Despite this growth, London’s social infrastructure lagged behind. Sanitation was non-existent, with periodic outbreaks of deadly diseases such as cholera and typhus; there was no welfare system apart from the very basic Poor Law and most children didn’t attend school. Furthermore, although most building development in this period was on greenfield sites, the poorer people whose housing happened to be in the way were unceremoniously evicted without compensation or regard for their prospects. Consequently, they were forced to find alternative accommodation further away from the centre but still within walking distance as otherwise there was little prospect of finding employment. The concentration of people in the centre of what was then a relatively small city was mainly due to a lack of affordable transport for the masses; outer expansion to areas that millions of commuters now know as Zone 2 was the catalyst for all this to change. Around a tenth of London’s population still lived in the City of London itself but the wealthier merchants, bankers and lawyers had moved out to the West End or the villas of Sydenham, Clapham or Stoke Newington. The phenomenon of separation of work and home that the railways would both enable and encourage had begun.

The early stages of a transport system were emerging, thanks to the ingenuity of a number of pioneering entrepreneurs. The first horse-drawn omnibuses were introduced on London’s streets in 1829 by a coachbuilder, George Shillibeer, who had seen them being successfully used during a trip to Paris. While promoting the idea, he was commissioned to construct and operate an omnibus for Newington Academy for Girls, which became the world’s first school bus. His company then went on to provide a regular service using twenty-seater coaches running between Paddington and the Bank of England in the City, anticipating almost precisely the route the Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground line, would take three and a half decades later.

Passengers on these early omnibuses paid sixpence or a shilling (2.5p–5p, or around £3–£5 in today’s money), which was still unaffordable for all but a small minority of the best-paid workers. The reporter in the Morning Post was impressed: ‘Saturday the new vehicle, called the Omnibus, commenced running from Paddington to the City, and excited considerable notice, both from the novel form of the carriage, and the elegance with which it is fitted out. It is capable of accommodating 16 or 18 persons, all inside, and we apprehend it would be almost impossible to make it overturn, owing to the great width of the carriage. It was drawn by three beautiful bays abreast, after the French fashion.’5 But the writer went on to warn rather presciently that there were concerns that the vehicle might find the narrow streets of the capital rather difficult to manoeuvre.

The other early form of public transport was the hansom cab. Introduced in 1834, the two-wheeled cab was pulled by one horse, making it cheaper than its predecessors. However, the drivers were infamous for their insolence and dishonesty, as well as, more worryingly, their dangerous driving, which was often made worse by their penchant for drink. Their fares, even before the customary overcharging, were out of reach of working-class Londoners but they were well patronized by the growing middle classes. Consequently, both forms of transport thrived with 3,000 omnibuses operating by 1854, a number that was surpassed by the number of cabs of various kinds plying their trade in the capital.

Given the cost of these new methods of transport, it was not surprising that it was the railways that were to become the real agents of change, particularly in respect of travel to and from work, because they could be both profitable and affordable. Their impact would be profound and long lasting. The success of the world’s first modern railway, the Liverpool & Manchester, which opened in September 1830, had not gone unnoticed in the capital. While it was by no means the first railway, a concept that had its origins in the wagonways that had sprung up in the seventeenth century, the Liverpool & Manchester was groundbreaking in a number of respects – it was the first railway to connect two major cities carrying passengers as well as freight in both directions on a double-tracked line with trains that were hauled by steam locomotives throughout the route.6 The railway was, therefore, revolutionary, changing the very nature of transport in Britain and then, rapidly, across the world as the widespread benefits of deploying this new invention were so patently obvious.

It was, though, no accident that the railways had first been developed in the North of England, rather than in the capital. The North was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, where the various inventions that were beginning to harness the power of steam ever more efficiently had been developed. Putting the source of this power, a steam engine, on wheels that ran on rails had slowly emerged as the best way to make use of the energy that had become available as the equipment became ever more efficient. It had taken years, decades even, for the idea of wheels on rails to emerge, after many false starts. Attempts to run wheeled steam engines on roads had floundered because the surface of early nineteenth-century highways simply wasn’t up to the task and steering for these behemoths had yet to be developed. So, iron wheels on iron rails was the answer as demonstrated by the successful opening of the Liverpool & Manchester.

After that, the railways never looked back. There were bumps on the way and a few half-hearted and abortive attempts to use horses rather than steam locomotives but essentially the development of railways across the world was unstoppable. By the start of the First World War, less than a century later, Britain would have 18,000 miles of railway, while the United States, which also opened its first railway in 1830, would have a quarter of a million miles, meaning that a staggering eight miles of track was built every day in the US for the whole eighty-four-year period.

Various extensions were soon added to the Liverpool & Manchester and a few other isolated lines popped up elsewhere in Britain, as far afield as Cornwall and Kent but not, at that stage, in the capital. London had, though, been the site of several early precursors of modern railways. The most significant was the Surrey Iron Railway, the city’s first line. Originally, the intention had been to build a railway or a canal between the Thames and Portsmouth, doing away with the need for goods to be carried by sea through the straits of Dover where the ships might come up against a hostile French navy. The purpose of the line was to serve factories that had sprung up along the Wandle, a tributary of the Thames that gave its name to Wandsworth; although navigable, it was a very slow way to transport goods. A canal was considered but proved impractical because of water shortages and the difficulty of improving the meandering Wandle.

Therefore, the promoters pushed through a Bill in Parliament in 1801 to build a line from a wharf on the Thames at Wandsworth to Croydon, with the option of later adding a number of short branch lines. The first sections opened in 1802 and the line was completed the following year. However, the idea of eventually reaching Portsmouth never got off the drawing board, although an extension to Merstham, further into Surrey, was completed.

The railway, which, impressively, was double tracked throughout, was operated by horses pulling wagons on rails that were just over 4ft apart, considerably narrower than the 4ft 8½in that later became the standard gauge on railways in Britain, most European countries and the USA. Unlike the railways that, within a few decades, sprang up throughout the capital, the owners of the line did not operate it themselves but, rather, allowed all-comers to use it in exchange for payment of a toll.

Unfortunately, the Surrey Iron Railway struggled throughout its life, with the owners unable to pay any dividends most years and only stretching to modest ones even when the business was profitable. Despite this, the line somehow survived the advent of the railways in London but its eventual demise was caused by the London & Brighton taking over part of the extension to Merstham in 1837, which damaged the Surrey Iron Railway’s profitability and resulted in traffic ceasing entirely in 1846. The authors of a book on London’s railways conclude that the Surrey Iron Railway and its extension, the Croydon, Merstham & Godstone, was never really viable once the ambitious aim to reach Portsmouth was abandoned: ‘The two railways were promoted as part of a trunk line and once that plan failed, the local traffic that they could attract was very limited. Under those circumstances, closure was inevitable.’7

London was also the site of one of the most significant demonstrations of the potential of steam locomotives, although it was a trial of the technology rather than a showcase for the concept of railways. Richard Trevithick is one of the lesser-known pioneers of the development of the railways, but he is deserving of wider recognition. Born in 1771 in Cornwall, where steam pumps to keep mines clear of water were commonplace, Trevithick first developed a more efficient version of James Watt’s groundbreaking steam engine, and then came up with the idea of putting one on wheels. After a successful first test at Camborne in Cornwall on Christmas Eve 1801 of his Puffing Devil, the subsequent trial three days later has gone down in history for all the wrong reasons. When the locomotive, which had no steering mechanism, got stuck in a gully, Trevithick and his team adjourned to the pub for a meal that history notes was of roast goose watered down with considerable amounts of ale. Unfortunately, Trevithick and his team left the fire burning in the engine, the water boiled off and the machine was destroyed.

Undeterred, his next invention proved far more significant. He realized he had to put his wheeled engine on rails. After producing a couple of locomotives for mines with mixed results, he visited London in the summer of 1808 to show off his invention on a circular track, ironically near the site of the present-day Euston station. His engine, developed as part of a wager, was playfully called Catch Me Who Can as Trevithick wanted to show that it would outpace and outlast a horse. Cannily, he built his track behind walls so that he could charge entry to those who wanted to see it and levy an extra fee on anyone who wanted to ride on a carriage hauled by his locomotive. Initially, the show was a success but interest soon tailed off and it closed down within a few months.

The fact that these two early experiments took place in the South-East was anomalous. It was in the North, and particularly the North-West, often in mines, where virtually all tests and trials of the new technology were carried out. London would, however, see the inauguration of a new type of railway, one that was ahead of its time and would result in the creation of a piece of infrastructure that, despite being little noticed by Londoners today, would have a profound influence on south-east London.

TWO

THE RAILWAY IN THE SKY

LONDON’S FIRST RAILWAY, the London & Greenwich Railway, had its origins in a previous project, the Kentish Railway, which emerged during the mid-1820s. This was a period of widespread enthusiasm for railways despite the fact that steam locomotives were very much still in the development stage and not yet a realistic proposition as the power source. The successful opening in 1825 of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, a primitive line mainly operated by horses but using some steam locomotives, demonstrated the potential of the technology and helped stimulate the first period of ‘railway mania’ as it became known. Proposals for lines were submitted to Parliament by more than fifty companies that together envisaged the construction of some 3,000 miles of railway lines. Most of these schemes never got past the design stage, but several were the genesis of what became some of the nation’s first railway lines.

In December 1824, the Kentish Railway published a prospectus for a line that would extend across the whole of Kent from London to Dover, serving towns and villages including Greenwich, Woolwich, Gravesend, Chatham and Canterbury. The idea was to use mainly ‘locomotive machines’ as the prospectus called them, although horses were expected to supplement them. Unlike many other schemes of this period, which tended to rely on back-of-the-envelope calculations, the Kentish Railway provided an impressively detailed forecast of passenger numbers and potential profit. In fact, it was far better set out than the equivalent pro-spectuses for many subsequent plans for more successful schemes.

The promoters estimated that, in the Kent countryside, the line would cost £5,000 per mile but recognized that closer to London, where potential for income was greater, expenditure would probably be double that amount. They calculated that there were around 150 horse-drawn coaches a day carrying passengers between Woolwich and London and generating £26,000 per year: ‘As locomotive machinery, moving at twice the speed and with greater safety, must in a very great degree supersede the coaches, the Company will probably obtain from passengers alone, independently of the baggage, an income of £20,000 or 20 per cent of the capital of £100,000 requisite to carry the railway to Woolwich.’1

Somewhat surprisingly, their chosen engineer was no less a figure than Thomas Telford, who had established his reputation as a road, bridge and canal builder, and an adviser to canal companies in bitter planning battles against their great rivals, the railways. Nevertheless, the promoters hoped that his name would attract the investment they needed to get the scheme started. They believed that once the section from London to Woolwich was completed and shown to be profitable, it would be easier to fund the rest of the line.

However, like so many other railway schemes of this era, their optimism was sadly misplaced. The company had sought to raise £1m (around £100m in today’s values) but investors were simply unwilling to risk parting with their money on such a radical idea as a lengthy railway running through London, particularly as the technology was in its infancy.

The only line that did emerge in this initial period of railway mania in the South-East was the Canterbury & Whitstable, a six-mile largely cable-hauled line that eventually opened in 1830 after numerous early travails and that has rather unfairly mostly been forgotten. Despite being technologically advanced, it proved to be a somewhat unsuccessful little railway. Built primarily to carry freight that had previously been transported on the winding River Stour as well as passengers, particularly those heading for the beaches at Whitstable, it was never financially viable. The railway was more expensive to build than anticipated and always struggled to pay dividends to its investors before finally being subsumed into the South Eastern Railway in 1844.

Nevertheless, the seeds had been sown for a railway running between south-east London and Kent, although, as was often the case in this entrepreneurial era, it needed the efforts and persistence of one man to champion the scheme and see it through to completion. George Thomas Landmann was a former colonel in the Royal Engineers and a civil engineer who had built forts to protect against potential American invaders when serving in the British army in Canada. His plan was for a railway of three and a half miles starting near the foot of the new London Bridge, whose recent opening in 1831 greatly improved links from Southwark to the City. Landmann envisaged a route that ran in a straight line to Deptford and then in a curve north-eastwards to Greenwich. Realizing that the first mile of the line would go through an already congested part of south-east London and would have to cross at least a dozen streets, he planned to run the railway on a series of viaducts that would limit disruption at ground level but prove exceedingly expensive to build.

The proximity of London Bridge station to the new improved crossing over the Thames was seen as attractive for workers in the City and the East End. Yet, in a way, this was premature as commuting long distances between work and home was not yet commonplace. Most of London’s workforce still lived within walking distance of their workplace and the capital’s economy had only just started to take off. However, Deptford and Greenwich, with a combined population of 45,000, both offered large potential markets for the railway. Deptford had a thriving dockyard with a huge workforce where many notable ships had been built; the surrounding area of market gardens and meadows was ripe for development that could attract more people onto the railway. Greenwich, with its long association with the Royal Navy, employed significant numbers of people in ship chandlery and other marine occupations. The little town was dominated by the famous Royal Naval College, but apart from the various maritime connections, it was the neighbouring park that offered the most likely source of income for the nascent railway as it was a favourite haunt for Londoners eager to escape the fetid air of the capital. The park could be reached easily, if somewhat slowly, by boat along the Thames, though, unsurprisingly, the ferry owners were quick to oppose the new railway scheme.

They weren’t alone. Objections came from the vast array of coach and horse omnibus operators on the busy road linking London and Greenwich where there was even a series of trials of ‘steam road carriages’ along the route. The most notable of these was The Era, a double-deck vehicle that accommodated six passengers inside and fourteen on top, and was said to travel at 10 mph. There were, too, a couple of smaller ‘steam road carriages’ running to Deptford, but while their portrayal in various surviving watercolours makes them appear well built and successful in attracting passengers, in reality they were simply too heavy to be a viable long-term proposition on the crude roads of the time, which all but disintegrated in wet weather.

George Shillibeer, who, as we saw in Chapter 1, had introduced the horse omnibus to London in 1829, was another vehement opponent of the railway. Having decided to shift his twenty vehicles to what he considered to be the lucrative route between London and Greenwich, he now faced the prospect of his business being overwhelmed by the putative railway.

Despite this fierce opposition from rivals and doubts over the ability of the London & Greenwich to raise sufficient funds for its ambitious plans, Landmann obtained Parliamentary approval for the line in May 1833. However, the level of scepticism that prevailed at the time can be seen in this dismissive quote in the Quarterly Review, a literary and political periodical: ‘Can anything be more palpably ridiculous than the prospect held out of locomotives travelling twice as fast as stage coaches… we will back Old Father Thames against the Greenwich railway for any sum.’2

The railway’s promoters secured Parliamentary backing by highlighting a number of advantages, some significantly less convincing than others. The line, they said, could be used to convey fire engines (a dubious suggestion); it would provide quick access for troops to Dover when completed (the Napoleonic Wars were fresh in the nation’s memory); and it could prove useful for transporting troops in the event of civil disorder (something that did, indeed, become commonplace on many railways across the world and had already occurred on the Liverpool & Manchester). There would, too, be fewer accidents on the overcrowded river and, rather fancifully, they suggested, less congestion on London Bridge from crowds watching the constant stream of boats sailing on the Thames. Safety overall was a big concern at the time and the promoters were keen to assure the public that many precautions had been taken to prevent not only derailments but also trains falling off the viaducts.

However, despite Parliamentary approval for the Bill, there was no certainty that money would be available to build the line. The prospectus, launched in November 1831, had sought to raise £1m, but investors were reluctant to come forward. With more than 19,000 of the 20,000 shares still to be sold, George Walter, one of the directors of the nascent company, went on a sales trip across Britain visiting brokers in Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool who were paid a commission to sell the shares. He also wrote various letters to newspapers, sometimes under pseudonyms, countering the arguments of opponents and stressing the value of the line. At the same time, pamphlets appeared, either directly or indirectly from the company, vigorously promoting the line. One, with the less than subtle title of The Advantages of Railways with Locomotive Engines, Especially the London & Greenwich Railway, stressed how the market gardeners of Deptford would be able to use the railway to transport their manure cheaply at night, something which, thankfully for passengers, never happened.

The most enticing inducement was the promise of annual profits of up to 30 per cent, based on highly optimistic predictions of passenger numbers and low estimates of costs, a not uncommon feature of these early railway schemes. Two further potential revenue streams were highlighted by the promoters. The area under the 878 arches on which the railway was planned to be built could, it was hoped, be rented out, and fees from the walkers on the roadway and gravel footpath that was planned to be built on each side of the base of the viaducts would be another potential source of income. In fact, in the early days of the line, when it only operated between London and Deptford, passengers from Greenwich were encouraged to walk along that footpath to catch the train at Deptford.

A cottage served as a temporary station and ticket office, with the back door of the dwelling leading on to the footpath towards Deptford. As the author of the book on the history of the line reports, this afforded a pleasant walk on a sunny day but, as it was unlit, ‘it was not the best means of reaching Deptford Station on a wet winter’s night for on the path from the cottage to the bridge… [was] a pond fifty feet long and 3 ½ feet wide in a direct line between the lantern [at the station] and the footbridge into which more than a dozen people had been lured by February 1837’;3 this was a mere three months after the opening of the line. Clearly, getting to the train was, initially at least, more dangerous than travelling on it. The path on the arches alongside the tracks was popular for a while, being used by around 350 people a day in 1839, a useful source of revenue for the railway.

Walter’s campaign to raise money was successful and ensured the London & Greenwich sealed its place in history as the capital’s first railway. With Parliamentary permission obtained, which always required the financing to be in place, it was time to start the lengthy and difficult process of buying out the landowners over whose property the viaducts would be built. Negotiations were undertaken with 500 separate owners and disputes had to be resolved by juries in more than thirty cases. Demolition work came next and its extent would be remarkable, setting an example that would be followed in the construction of several other terminuses and their lines out of London. Most house demolition was justified on the grounds that the dwellings were insanitary, cholera-ridden slums and therefore it was in the public interest to clear them. As much of the clearance work for the line was carried out in Southwark, an area of mostly poor housing, the London & Greenwich had a strong case. Nevertheless, some residents of the most insalubrious slums in Bermondsey were reluctant to move, and threatened violence against the navvies constructing the line. Further towards Greenwich, however, there were fewer houses and it was around Corbett’s Lane, Bermondsey, the halfway point, that work started in April 1834 on the viaducts towards London.

The scale of the enterprise was unprecedented and the initial work of building the viaducts was an object of great curiosity for Londoners. In fact, the huge number of bricks used in their construction resulted in a shortage for housebuilding elsewhere in the capital. At the peak of the work, a remarkable 100,000 bricks were being laid every day. More than 600 men were employed, and by the autumn of 1835, a temporary single-track railway to transport material had been installed on 540 completed arches. A section of the path had also been completed and earned the first income for the railway company.

With vast quantities of bricks set aside for the section towards Greenwich, the company hoped to open the whole line by the original scheduled date of Christmas 1835. In truth, however, despite a further 150 men being drafted in, the deadline was unachievable. Further delays occurred when two unfinished arches in Bermondsey collapsed one night in January 1836, fortunately not resulting in any injuries or fatalities, which would have been the case had the incident occurred during the day. The most serious setback was caused by the need to comply with a section of the Act which specified that the bridge over the River Ravensbourne had to be moveable to allow boats through, even though the Ravensbourne was little more than a wide stream (this could have been avoided with permission from all the occupiers of the local quays and wharves but that proved impossible to obtain). After much procrastination, a drawbridge was built but it is doubtful that it was ever raised to allow any boats through.

The men building the line were not averse to an occasional fight and at weekends pitched battles took place between the English and the more numerous Irish. Most of the navvies lodged around Tooley Street, adjoining today’s London Bridge station, and the company decided to segregate the two groups in areas called ‘Irish Grounds’ and ‘English Grounds’, the latter of which still survives as a small street running parallel to the Thames.

The various trials of technology attracted huge interest from Londoners who had not, apart from Trevithick’s brief efforts two decades earlier, seen working steam locomotives. Extensive press coverage of every aspect of the railway’s progress further fuelled interest. Despite an occasional mishap, such as the collapse of the two arches in Bermondsey, there was sufficient confidence in the technology to enable the first section of the railway to be opened in February 1836. This ran between Deptford and Spa Road, about a mile short of London Bridge, owing to the westernmost arches being the most difficult to build in a densely populated area. This meant that the wholly inadequate ‘station’ at Spa Road could claim to be London’s first railway terminus. However, only the most obsessive trainspotter would accord it that title since it was a makeshift affair with virtually no amenities to serve the travelling public. According to the author of the history of the London & Greenwich Railway, ‘Spa Road station in 1836 consisted of the wooden staircase on the south side of the viaduct and a small wooden booking office at ground level [and] a narrow platform to accommodate about six passengers was provided on the viaduct’.4

It seems from contemporary accounts that the platform was barely a yard wide and was situated between the tracks, meaning that people had to climb up carriage steps to reach the compartments. Apart from the steps up to the top of the viaduct, there was no building or protection against the elements at Spa Road, which the railway treated as a ‘stopping place’, rather than a station. The reason for this parsimony was that the railway had been reluctant to provide any services to Spa Road as Landmann and his fellow directors wanted to make sure that London Bridge became the key station serving the western end of the line. It was the Commissioner of Pavements, a Crown agency, that insisted on the railway serving Spa Road as it reckoned this was the most convenient point for passengers to reach Westminster Bridge.