8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Kamera Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

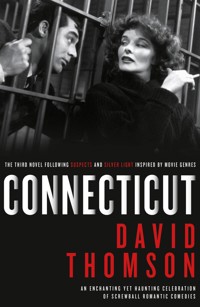

The third novel in David Thomson's series inspired by movie genres - an enchanting yet haunting celebration of screwball romantic comedies. In 1985, with the acclaimed Suspects, and then in 1990 with the exhilarating Silver Light, David Thomson delivered unprecedented fictions in which the characters were figures from film noir and the Western. Now a trilogy is completed with Connecticut. Why Connecticut? Because that lovely, liberal state has been set aside as the resting place for every disturbed person in the nation! At first, this seems like an opportunity for meeting up with the merry ghosts of Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Carole Lombard, William Powell and Margaret Sullavan. We get glimpses of Bringing Up Baby, My Man Godfrey and The LadyEve. But then the wild comedy darkens as we realize that Connecticut itself is on the edge of a demented and cruel war that challenges all its inmates to keep seeing the comic side of mishap and madness. The trilogy is revealed not just as a set of dazzling stories. But a commentary on how far we have all been steered towards delightful but dangerous fantasies by the movies. Aren't we all screwball now? Is Connecticut safe to visit?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 261

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR DAVID THOMSON

‘Witty, expansive, convincing, honest, more than a little mischievous and, so often, absolutely on the money. Thomson’s voice is one of the most distinctive and enjoyable in film criticism. It leaps from the pages of this spruced up classic like flames from a bonfire… For as long as there are films worth writing about, Thomson’s opinions will remain worth reading’ – Telegraph

‘David Thomson is a giant in the world of film criticism, and his book is the chest-crusher you might expect: erudite, delightfully tangential and surprisingly polemical’ – Times

‘Full of unexpected insights, it’s learned and beautifully produced. It’s also tremendous fun’ – Guardian (Books of the Year)

‘Chatty and authoritative… Both wonderfully informative and a beautifully written paean to the movies and their continuing ability to inspire and enthrall’ – Sunday Times

‘The greatest living writer on the movies’ – New Statesman

‘Thomson at his best (which is, bluntly, better, more intriguing, more infuriating, more fun than just about any other critic)’ – Sight & Sound, the BFI Magazine

‘Rigorous and rewarding, and a page rarely passes without insight’ – Independent (Books of the Year)

‘Thomson proves anew that he is irreplaceable… His monologue has blossomed into an unlikely, searching dialogue about what to value in the movies – how to love what’s come before without nostalgia, and how to find the courage to demand more from the stuff being made right now… Deservedly treasured… One of the most probing accounts ever written of a human being’s engagement with the movies’ – New York Times Book Review

‘Delicious. One of the best and most useful books written about the movies’ – San Francisco Chronicle

‘We cannot erase the perplexity that comes from assuming our mental health practitioners are sane – just because that is their aim in life. Don’t a patient and a doctor need something in common? And doesn’t the patient dictate the rules and rhythms of this game? Under some guise of being unwell, he or she tells a story. So doesn’t the doctor need to be a little disturbed, just to keep up?’

Dr Frederick Kinbote, private conversation

‘Accordingly, we should regard the midsummer’s eve in the Connecticut forest not as the preparation for a wedding ceremony but as an allegory of the wedding night, or a dream of that night.’

Stanley Cavell, ‘Leopards in Connecticut’, Pursuits of Happiness (1981)

for Douglas McGrath

A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER

Our author, your author, has never lived in Connecticut – but there are so many places he has not lived, and that shortcoming has not deterred him. (We can’t be everywhere – we couldn’t even feel that possibility until the movies came along.)

But our man is resigned to living in his head, and suspects that most people are familiar with that zip code. The head can create many locations that have enough external ‘reality or atmosphere’: a job, family life, a place, common interests, being American, industrious wickedness, tragedy, whatever. You know those dreamy aspirations and the generous ways existence plays along with them.

Our author’s residence was more truly the movie screen. And that’s how he has lived in Connecticut – in filmslike Bringing Up Baby, The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels, My Man Godfrey… the list goes on.

Connecticut was often an idealized setting for retreat in films of a certain era (just before the War – which one? you ask!), an Arden or an al fresco canvas where people who made books, theatre and movies (and money) often liked to go, to ‘a weekend placein the country’, where they could relax, run a little wild, andthink up their next projects as if they were sane and businesslike ‘successes’.

Think of Connecticut as the hoped-for countryside in an age when the city was beginning to be a collection of solitudes, crammed together, like a prison. The rural state was a place for ease and abandonment, for screwball comedy, and wondering if you were in love. That is my Connecticut, and I like it in black and white.

It is where the actress Margaret Sullavan chose to live when she fell out of love with the movies, yet not quite aware how being there could endanger her precious yet precarious marriage to Leland Hayward. It was inConnecticut, on 1 January 1960, in a hotel in New Haven,that she was discovered dead.

We’ll come to that, alas.

PART I

ONE

There I was, busily writing my book about the kiss in cinema – I had a deadline – when these two strangers walked right in and told me I had to go to Connecticut.

‘Why? Why there?’ I said. Haven’t you felt the dread of being abruptly taken away?

My lithe young research assistant from the Dominican Republic, a danseuse, so alert, trembled – as if perhaps she had inadequate papers – at this intrusion. Then she simply slipped away: I’ve never seen her since. Let me tell you, researchers like that don’t grow on trees.

The only thing that happened in the face of my protest was that the two strangers in gray and grey, my ‘they’, gave me the civilized runaround. I felt like a ball bouncing off walls, unable to avoid the thrash of their rackets.

‘Oh, it’s lovely in Connecticut,’ rhapsodized number one. ‘This time of year: summer, with cuckoos in the distance.’ Who expects such feelings from uninvited strangers?

‘I would go to camp there as a lad,’ added number two. ‘Happy days. Blue nights. The pals we had then. Marshmallows? I believe we had marshmallows. Doesn’t one toast them over a camp fire?’

‘Connecticut’s days away,’ I told them. No one does geography any more. I like to read maps, as if they were books. But the point about Connecticut, it seemed to me then, was its rural remoteness, a sense of never needing to go there, while entertaining idle thoughts of it as an innocent retreat. If one ever felt a need to escape.

‘Its distance is its charm,’ explained number one.

‘So the closer one gets,’ I interposed, ‘the less charming it becomes?’

‘Don’t be so lawyerly,’ said number one. ‘It’s not what one expects from a learned fellow with your credentials, writing an entire book about the movie kiss.’

‘Connecticut has a gentle, pleasing shore,’ number two advised. He could have been quoting. ‘With many sylvan prospects in the interior.’

‘Fuck Connecticut,’ I said, just to be clear about my position.

‘You can’t.’ One smiled at two. ‘That can’t be done.’ He seemed rather smug about this.

‘No physical dignity in it, much less satisfaction,’ said his friend. Have you caught their rhythm by now? The way they took turns. Their lines might have been scripted for them.

‘You’ll feel calmer there. It’s known for being salubrious, soothing and –’

‘Very quickly you’ll feel better,’ the other interrupted.

‘Better?’ I pounced on that. ‘Who – may I ask? – has decided that I need to be better?’

‘Look,’ – this was number two – ‘it’s where people like you go. In the nicest way, old sport. There are as many clinics there as wayside inns. Be grateful for small mercies.’

Number one chimed in: ‘It’s all a matter of safety.’

‘Safety?’ I asked. ‘Whose safety?’

‘Yours, old chap.’

‘What do you mean people like me?’ I said. All this old chap, old sport, smokescreen: it was getting me down.

There was throat-clearing between one and two and then they explained it to me.

You may have known this, but I had never heard it before (and I do think it has been kept suspiciously quiet): Connecticut, the entire enterprise, all 5,567 square miles, the Nutmeg State, Branchville and Darien, New Haven and Hartford, Brookfield and Hazardville, Windsor Locks and Crystal Lake, Sandy Hook and Southbury (you can look them up – you’ll need a map), its varieties of landscape, town and country, the condition, the state, the idea, was a mental hospital, or reservation, the way Yucca Mountain in Nevada once upon a time was where we were going to put all our horrible, shit-faced nuclear waste. Those were the days. If only we could have them back.

‘But I’m writing a book,’ I insisted.

‘Nearly everyone in Connecticut is,’ said number one reassuringly.

‘It helps to pass the time,’ number two concurred. ‘And I hear it can have some therapeutic benefit, over the long haul.’

‘You said “quickly”,’ I pointed out. ‘Quickly I’ll feel better. You did say that.’

He sighed. He rolled his eyes at the notorious volatility of ‘creative’ people. ‘There you go again,’ he said.

‘You’re really too suspicious.’

‘Paranoid.’

‘Not well.’

‘Nuts.’

‘Loopy.’

‘Off the deep end.’

‘Screwball.’

* * *

It wasn’t my doing. They told me to think of myself as someone in a story, but that was not helpful. I couldn’t tell whether I was meant to be a character or an author. It didn’t matter what I said. They had a grammatical inversion ready for making any defense seem like self-incrimination. I protested that I was in the middle of a sentence when they had knocked on my door, and number one just shrugged a shoulder and said, ‘Most of us are, most of the time.’

Did he mean the life sentence? That is one way of looking at things. I nearly wrote a movie once, about a fellow living what seemed like an ordinary, humdrum life, until bit by bit clues appeared to suggest he was actually in some kind of institution, an asylum or a kindergarten. An intriguing set-up, maybe, but I never knew how to end it. If you have any ideas…

Here is the odd thing. I’m warning you. No matter how wronged you are, you can begin to think you do need to go to Connecticut. Is there a fundamental shame just waiting to be identified?

‘So what are you thinking now?’ asked one.

‘Yes, I thought I saw some secret thought,’ said two.

There was an air of mocking hide-and-seek in their interplay. I felt I was hiding in a doll house with huge faces gazing at me through its tiny windows. It felt slightly lewd.

‘I really don’t remember,’ I said, and folded my arms like a determined child. ‘After all, I think of many things.’

‘Oh, my word, isn’t he a marvel?’ said one. ‘Too many things, I daresay.’

‘Loss of short-term memory is common in your condition,’ said two. ‘It’s just one more bit of proof. I’ll make a note of that.’

‘I wouldn’t be surprised,’ said one, ‘if you don’t even remember our names.’

‘You never told me!’ This made me furious. ‘You never said your names. Come to think of it, you offered not a jot of identification or authority.’ I wondered if that omission might still keep me out of Connecticut.

‘Of course, we told you,’ cooed number one. ‘Let me say, old bean, in the friendliest way possible, you may be a little farther gone than you realize.’

Two chipped in: ‘As for our authority, I hope one glance is sufficient. We’re hired for that, you know. One and two. I mean to say, no one ever asked John Wayne about his authority, did they? Do I mean John Wayne?’

‘Of course, you do,’ said number one. ‘No one ever doubted the Duke. His authority was as plain as the nose on your face.’

One took a couple of steps sideways, as if to reappraise my nose – and I can tell you that I have never had a discouraging word about that part of me. Indeed, several ladies have noted how tidily it fits during the act of kissing – which, as you know, is a professional matter with me.

‘You never uttered one word about your names!’ I insisted. I was getting scared and angry, and often in those moods I need to laugh out loud or have other people laugh at a joke. ‘You’re just the party of the first part and the party… of the eleventh part,’ I added. Eleven, I find, is often comical. I don’t know why.

‘No,’ said one, shaking his weary head sadly. ‘We are better placed as numbers. You’ll learn to live with it, if you’re patient.’

‘Why mention patients?’ I asked.

‘Why, indeed?’ despaired one. ‘Instead, let’s think of you as our companion on the journey.’

‘That sounds agreeable,’ said two. ‘You’ll have the back seat of the car to yourself. You can stretch out, if you want to. Let it be a vacation. The leather there is like chamois, and there are magazines in the pockets behind the front seats. Are you a golfer?’

‘I am not,’ I said. I tried to make golf sound like an unnatural or unAmerican activity.

‘Pity,’ said one, ‘I seem to remember some golf magazines in the flap. But I think there’s the usual departmental porn, too. More to your taste, kisser?’

‘I abhor pornography,’ I told them. You have to make some things clear as soon as you can.

‘You’ll get over that in Connecticut,’ said one – really, I found it more comfortable to think of them as numbers. ‘Connecticut is vigorously against abhorrence, you know. Its liberalism is a byword, and that will bring enlightenment in your treatment. All the latest research – whatever. You’re a lucky fellow. You do realize, before Connecticut things were on the primitive side, brainbox-wise, if you know what I mean.’

I didn’t know what to say, but like most of us I harbored grim pictures of how the allegedly insane passed decades and decay in state hospitals for the some-such. I could hear the groans, the screams, the announcements of drab routine, and the bored mirth of the guards. In my head I had been there. You too?

‘Connecticut can go to hell,’ I decided to say.

‘So be it,’ said two in an easy-going way, ‘but let’s get you there first. And don’t be taken aback, old boy, if it turns out heaven.’

‘Anyway,’ I remembered. ‘Show me your identification. Just exactly what are you two? To whom do you report?’

‘To whom?’ echoed one, and two chuckled in an amiable way. Sometimes laughter can chill your marrow.

‘What are we?’ said two. ‘We’re company for each other – what does it look like? And we’re here to take you to Connecticut.’

‘Do you have a requisition order?’ I demanded. ‘Do you have a note or a chit? Some paperwork?’

One looked at me in a pitying way. He shook his head and seemed tired, or was it just nostalgia, a memory of the time when authority had meant something? ‘No, we don’t have a chit, not even a billet-doux. But we have you. Come along, kisser, like a good boy. You don’t want us to summon up a touch of the nasties. Do you?’

I didn’t say anything. Not yet.

* * *

I awoke slowly in the back of the flowing car. My waking and its motion merged, like fluids in suspension. That restful coming back from wherever – sleep, the night, anxiety – hadn’t happened to me for years, so I tried to make a gradual act of self-composure. Usually in those days I woke up suddenly as if a gun had slammed or a door been fired. So it was pleasant to see a passing canopy of foliage and trees watching over me. I felt I was being looked after, on an early summer afternoon. Isn’t that what we’re hoping for? I yawned, I stretched, I was at ease, even if the heads, one and two, were still there, like placards in the front seats.

On that afternoon, my dreaming tended in opposite directions: a part of me was kissing Grace Kelly (or was it Sandra Dee?); another wondered if I could feel a tumor growing in my head. Sometimes it can be best not to puzzle over one’s own mind.

‘Good nap?’ suggested one. He did not look back at me, but I saw kind eyes like gray pigeon breasts in the rear-view mirror.

‘Must have been,’ I realized. I was still having to appreciate what had happened. ‘Yes, a satisfying sleep, quite a good one. I feel I got some rest. Reminds me of Sussex.’

‘Ah, Sussex!’ sighed one. ‘Did you ever know Eartham Woods?’

That name struck a chord. ‘I did once,’ I told him. ‘Yes I did.’ (But this was no time for heartbreak – you see, I had my own life, kept it to myself. I was very far from just their character.)

Two said, ‘We’re going to stop for a leak and a sandwich. Interested?’

‘I never eat leeks,’ I said. ‘They don’t agree with me.’

Two laughed in a good-natured way. He turned and looked at me. ‘Not the vegetable,’ he explained. ‘A pee.’

‘Yet a pea is a vegetable, isn’t it?’ said one, and the three of us chuckled together. It was an escape from our tension. Who can keep that up? I can but I suppose that does seem hostile.

‘A pee might be handy,’ I said. Might be very welcome. Like all ordeals, stress has its consequences. I suppose on the trains, to Auschwitz or wherever, people relieved themselves in their clothes, as they stood. (No, I’m not going to cut that just because it’s upsetting. What’s a story without some dismay?)

The car pulled off on the side of the road with softened bumps and the squeak of grass against the tires. We were in the heart of a forest, not dense to the point of impenetrability; there were glades and clearings, natural resting places and what looked like promising picnic spots. But there was not another person in sight. It was what you like to expect of the depths of the countryside, in the forest. I could see birds spinning lazily between the treetops on thermals of warm air.

There were ferns beneath the trees that came up to our waists, and that thick brewery aroma of growth cooking humidly in June and July from ground so soft it might be flesh. I guessed there could be rains here, thunderstorms, or temper fits in the weather. The ferns had the span of an eagle’s wings, with every arrowed frond flawless, every serration immaculate and shivering. I had not encountered nature in so long, or so luminous in the shade from the trees.

There I was, there I had been, attempting to compose a provocative gift book on kissing in the movies (it was that or car crashes), recasting every sentence, laboring, striving, organizing, and suddenly I was in a part of the forest, one small aspect of it all, without any other observers except for one and two, and the profusion of unimpeded growth. There was no anxiety, even if an owl and a fox had rhyming eyes of knowingness at what might come.

‘It is lovely,’ I agreed. The word came out like a sigh. I heard myself say it.

The three of us walked into the woods and each found a tree to pee against. The glossy ferns bounced and swayed as I touched them. I saw two chipmunks watching me, as if no humans had been there before.

I could see the distance through the trees. There was the fissure of a path, or some kind of passage, to get away, like the vein in a leaf.

‘You could escape perhaps,’ murmured one, beside me, surveying the way into the woods. ‘You’re younger than us – if you can run.’

‘I was a promising half-miler once,’ I admitted, amazed at my impulsiveness. ‘1 minute 53 seconds, personal best,’ I said and I felt my muscles tighten.

‘Really?’ said two. He seemed impressed, as if thinking of past masters, Lovelock, Whitfield, Snell, and Wottle, half-miling smilers. ‘Not much point, though,’ he added.

‘Oh, why not?’ I wanted to know.

‘We’ve been in Connecticut a couple of hours,’ said one. ‘You were asleep when we crossed the state line.’

‘This is Connecticut?’ I cried. Had it happened just like that, without any sign of border patrol, confinement, stockade, detention camp or customs? Indeed, this place felt airy and open, balmy and fragrant, it –

‘We did tell you how pretty it was,’ said one.

‘I could still escape,’ I said. I reckoned that if I took that faint path it would lead me on, running, running.

One was zipping up. ‘No,’ he said, ‘you don’t understand yet. You see, you’re here now. You’re in the state. Wherever you run to, it’s Connecticut. You can no more escape than you can stop being an Aquarius, or left-handed.’

‘I was never left-handed,’ I said, but I was stung that they knew about Aquarius.

‘I mean if you were. Have a sandwich?’

They had a brown paper bag. Two opened it up, miming surprise. ‘Take your pick,’ he said. ‘We’ve got a BLT, a ham and Swiss, and a roast beef, with all the trimmings, but no onion – I hope you won’t miss that. We detest the smell of onion in the car. What do you fancy?’

It felt like a trap or a trick question in one of those party games where you can be found out. Ham and Swiss was my favorite, but why should I tell them that, my warders? My hijackers, even if it was such a fine day in Connecticut and they were being so affable. You have to stay on your guard.

‘You pick first,’ I suggested. It was ordinary civility.

One and two looked at each other, hummed a little tune I didn’t quite recognize (it was on the tip of my tongue), did as I asked, and handed me the ham and Swiss. It was limp and warm in Saran wrap. But it was a hefty beast, a meal, and I could see the bread had seeds and oats in it.

‘That all right?’ asked one.

‘I won’t complain,’ I said.

‘We could swap,’ offered two.

‘Not unless you prefer to,’ I countered.

‘It’s for you to say,’ said two.

‘You’re quite sure?’ asked one, and his tone of voice seemed to insinuate that certainty could be a rash move in the game. Whereupon, a friendly male voice called out from the forest. There he was, strolling towards us with light behind him, without explanation, but an ideal figure to illuminate and define the wilderness. He was epic, but casual, and quite endearing. It was a tall, untidy fellow, coming out of the forest, and he was saying in a cracked baritone, ‘Gee whiz, any chance you fellows have another of those sandwiches? I’ve got a hunger on me, I can tell you.’

To be exact, he said this twice; he had to repeat the line and his entrance, having flubbed the first attempt when he seemed to say, ‘I’ve got a hanger on me, I –’. A hushed voice from somewhere said, ‘Let’s go again.’ So, obediently, and without complaint, he turned around and came strolling out of the trees, take two, as fresh as a breeze, as if for the very first time. And now the line was right – without so much as a clapper-board to mark it. He was a natural, momentary and authentic. There could have been a statue of him there in the glade, bronze, smiling in the sun, careless of destiny or debt, ‘The Rambler’.

This fellow gave every appearance of the classic hobo, a bum, a tramp, a gentleman of the road. He wore a battered fedora, a faded white shirt threadbare at the collar, a jacket with one pocket hanging loose. His corduroy pants were so worn I thought I could see the white of his legs. He had on what seemed to have been alligator shoes once, but they had split open so that his bared toes might have been the alligator’s teeth.

Best of all, in terms of expectations, he had a stick over his shoulder, a length of ash, and a full swag bag tied to its end, red with white polka dots and bravely cheerful, even if it let one surmise that a man’s life and possessions, his past and his memories, might amount to no more than the size of one oven-ready turkey.

‘Hi, gents,’ he said, and he had a smile for the three of us. ‘You can call me Sully. Two weeks ago I escaped from a chain gang. How about that?’

His head, his hands and his throat were all tanned, like furniture, not when polish or wax have been applied, but from weathering and the abrasion of use. It was not a darkness gathered on a two-week walk, or even from months on that chain gang. Deeper down it was good old Californian suntan. He might have been a lifeguard on Santa Monica beach, waiting for kids to splash and cry out in the surf, and he had the shoulders of a swimmer.

‘I didn’t realize we had chain gangs still,’ said one, breaking his sandwich in half and giving a piece to Sully. We all did the same, so Sully found himself the owner of a small feast.

‘You bet they do,’ he said. ‘Down south of here a way.’

‘Where was that?’ asked two.

‘You know, they never said,’ Sully explained. ‘But it could have been Georgia, maybe, or Alabamy.’

‘You’ve come a long way,’ I observed. The sandwiches were good and they enhanced our new comradeship.

‘Riding the rails,’ said Sully. ‘You can wake up in a different world and weather. Where you guys headed?’

‘We’re going to Dr Bone’s place,’ said number one. ‘The Retreat. It’s not far now. Fine establishment, feels like a country club and it works wonders.’

‘Sounds swell. Think I could ride along?’ asked Sully.

Whereupon, one and two looked at me, as if it should be my decision. That was unexpected, but I didn’t feel inclined to argue, not when I liked this wanderer. ‘Why not?’ I said.

‘Well, that’s bright of you,’ said Sully. ‘That’s decent, I gotta say. It’d be pretty nice to have someone to talk to. Walking in the woods is fine, especially these woods here. Good woods, they are, the real thing. But you can get to wondering if you’re ever going to meet a soul again. And if you do, whether you’ll still know words and manage to utter them. I mean, a fellow can be walking along and talking to himself, the way you do as a kid if you’re carrying a message. Remember that sort of thing? Why, once I had to keep it in my head, a message from my father to my mother, for more than a couple of miles, that he wouldn’t be home that night. And he wasn’t – not ever again. Last I saw of him. That’s how I was feeling – darned lonesome – coming through these woods and just not knowing where I was but –’

‘Oh, enough, please,’ said number one in a weary way. Somebody had to stop Sully. A bronze Rambler is all very well, but a speech of more than four sentences pushes your luck.

By the way: I don’t think I quite took this in, but when one and two put me in their car – back in the city – it had seemed a stylish but modern limousine. But now, in the woods, in a very well-kept way, it felt somehow older, a classic if not quite an antique. As I say, I did not fully appreciate this at the time. But it was so long since I had been in a vehicle that had the space, the calm, the soft engine hum, and the cool leather of a civilization.

* * *

In the car and on our way again, Sully and I were together on the back seat. It occurred to me in the confines of the car, despite the perfuming of its interior, that my new pal from the open road might have a vagrant aroma – unlaundered clothes, failure to find a decent barber, a rough diet, and even the habit of taking a dump in the undergrowth, that sort of thing. Yet, closer to Sully than I had ever been, all I could detect was what I thought was Old Spice, and recently applied. The more I looked at him the more I began to wonder if his nutty sheen and his outlaw air of being beyond the reach of social services were something of an act. His teeth were outstanding and bright from a recent whitening that did not fit my sparse knowledge of life on rural chain gangs. But common sense doesn’t always do as it’s told, so I was a little suspicious of Sully my new comrade and chance acquaintance. Who knows these days if it’s life in the raw, untrammeled, disorganized, at random, one has wandered into, or –

‘Used to go everywhere in these limos,’ said Sully. ‘Something you get used to, I won’t lie to you.’

He had stowed his stick and swag bag and he was examining the furnishing of the limo.

‘There should be a handy cocktail cabinet around here,’ he mused, searching in the gloom. ‘Fancy a stinger? I used to make a good martini, set you up, so bracing it was just as if someone told you your fiancée was dead this morning. Ever had a fiancée die on you?’

‘Never,’ I insisted. I had no idea who was listening, or what was being recorded.

‘Funny feeling that,’ said Sully. ‘Breaks your heart one minute, then the next it gives you fresh hope. I made a picture once about a fellow on his honeymoon. This lovely new wife he has. But already before lunch he’s wondering if he’s bored. Open-minded. Second day, he’s on the beach, fetching a praline daiquiri for his bride, when he meets another woman and knows right off he has to marry her.’

I was perplexed. ‘So this just married fellow divorces his new wife and marries another?’ Could that be an automatic process?

Sully was nodding enthusiastically. ‘Picture was a hit. A lot of folks, on their wedding day, you know, they’re thinking of someone else. Is that a hoot? Surveys say so. Motion picture polls.’

So I hadn’t been crazy! I thought I had detected the assurance of a Paramount in Sully, an air of unhindered romance from the silver screen and the energy for following any crazy story under the sun. ‘You are a movie director!’ I was delighted for him, for both of us.

‘Was is the word,’ said Sully. ‘I was a wow, too. Hey, Hey in the Hayloft, Ants in Your Pants of 1939 – did you catch those?’ He strode on through my ignorance. ‘I had hits like apples. Then I was the chump. Decided I was tired of silly comedies and I was going to take to the road, see the nation, get acquainted with hard times – that sort of stuff. The studio thought I was bananas. And they were right. Where did my travels lead me? – to the chain gang, that’s where.’

‘But couldn’t you still recover?’ I wondered, full of the romance of movie ups and downs. ‘If you went back now, think of the story you’d have to tell. A classic comeback!’ I wanted to encourage him. I wanted to see that movie, or be in it.

‘Well, I appreciate that,’ said Sully. ‘And I take it as a mark of friendship, but the powers that be, from Universal to Metro, they have a fixed idea now that I’m crazy. Why do you think I’m here, hiking through Connecticut? No second acts, buddy, no second chances. Ben Hecht told me once, never go to the bathroom at a party, and never give the audience an interval.’

If friendship was being proposed (despite the delicacy or uncertainty of our situation) I thought I would plunge in and establish myself. ‘As a matter of fact,’ I told Sully, ‘I am at present writing a book on the kiss in the movies.’

‘You are?’ His eyes lit up and he turned to examine me more closely. I suppose he had been taking me for granted. ‘A whole book? That’s a hell of a thing. Friend of mine invented a kiss-proof lipstick.’

‘How did that work?’

‘I never knew. I guess, you could kiss all day long and the rose carmine never smeared. You were just as perfect as when you started.’

‘Yet I like the look of red staining the mouth,’ I told him.

‘Well, sure, in life, I guess.’ He spoke of that domain as if it was a foreign country cut off by quarantine restrictions. ‘This was for the movies. I mean, if you’ve got Fonda and Stanwyck only until six o’clock, a smear-proof lipstick can save you time on make-up.’

‘Did you ever direct those two?’

‘Positively the Same Dame, it was called. Stanny was a peach to work with but Fonda could be a pill. Still, that worked out on this picture. Her character had to tease his a lot, but I never told him it was a joke. So he got more uncomfortable while she was giving him a boner and he couldn’t stop it. Of course, we were in close-up, mostly, so you didn’t see the boner. But those two knew about it, believe me.’

‘