Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Honno Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

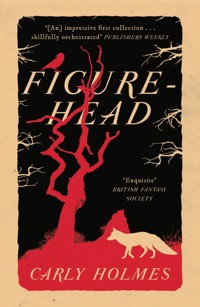

"Beautifully written, tender and terrifying." UNA MANNION Annie surrendered her fantasy of travelling the world, settled instead for marrying her beloved Peter and becoming a mother. When her two youngest daughters – her Crow Face and her Doll Face – perform a seemingly impossible act of levitation at a family picnic, Annie realises that they are truly extraordinary. Magical. And it's her role to protect them. With growing paranoia and a bitter fatalism, she spirits her daughters away from their home and the wreck of her marriage. But she commits a terrible, unthinkable, unmotherly act on the way. Crow Face, Doll Face is an uncanny, brooding tale of domestic disturbances, dysfunctional families, flawed mothers, and unfulfilled dreams. "I can't think of anyone who's currently writing more assuredly, or more enjoyably, in the fantastical tradition of Angela Carter, Emma Tennant and Elizabeth Bowen." STEVE DUFFY "Deliciously unsettling… delicately peels away the layers of ordinary family life to reveal dark truths underneath." CATRIN KEAN "Unflinching in its authentic and raw portrayal of the complexities of motherhood." PHILIPPA HOLLOWAY

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 315

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CROW FACE, DOLL FACE

Carly Holmes

HONNO MODERN FICTION

For my very own Crow Face Doll Face. You and your brother Panda are the loves of my life.

CONTENTS

I

CROW FACE

I used to have three daughters and a son. Mealtimes used to be a snatch-grab, a shriek, a hubbub of spilled drinks and peas ping-ponging the length of the table.

We used to be average, as families went. Days bookended by squabbles over socks and bedtime stories, a roast lunch on Sundays and biscuits traded for baths. First there was Julian, then Elsa, and then Kitty, each born exactly thirteen months apart. I yearned for a flock of five but, as one year folded into another with no clockwork pregnancy, bargained with the gods for a flock of four. Just one more and I’ll visit Mother every weekend and prick myself on the thorns of her bitter widowhood. Just one more and I’ll never complain about the press of muddy shoes across mopped floors again.

The gods listened and mulled it over and I got my wish, two long years later. Leila. The Crow. I birthed her on a pile of cushions in the living room while Peter wept and knelt beside me, grey-cheeked as he patted the air beside the judder of my spread thighs and averted his squeamish gaze from the bloody eye at the core of me – the pulsing hollow where our fourth child beat her way towards life.

He was too late, or too clumsy, to catch her as she wailed into the world, and I was too weak. She would have slipped from the cushions and onto the cheap sheen of our grubby carpet if Kitty hadn’t leapt from her hiding place behind the sofa, the blanket from her doll’s pram trailing from her fist like a victory flag, and scooped up the tiny bundle of gore. She should have been terrified by the sight of her mother made monstrous by pain, terrified of the rich stench of blood that clotted the cushions and spattered my legs down to the ankles, but she only had eyes for the baby. Her face was a crinkle of wonder.

She clutched Leila against her chest and stared down at the blanket-wrapped squall of her sister for a few rapt seconds, then she raised her up, that tiny head wagging unsupported on its fragile stem, and she kissed her again and again. Exuberant, lusty kisses. Blood and fluid smeared across her lips, but she didn’t wipe them away. She didn’t even seem to notice. ‘Doll Face, her head,’ I whispered frantically. ‘You have to support her head!’

‘She looks just like a little baby crow!’ she said, more to herself than to me or her father. ‘Look at that shiny black hair, and that little beak nose. Hello, Crow.’

She turned and marched towards the door, dragging the messy aftermath of birth with her, tugging the cord that bound Leila to me so that I felt it shearing away from my bereft womb. I sobbed a refusal and twisted on my pile of cushions, trying to roll over onto my knees. Peter bobbed and jerked across the room to retrieve the daughter I hadn’t yet touched, his long legs dipping at their joints from the long hours of crouching and the shock of the moment. He reached Kitty as she fumbled for the door handle, gently taking Leila from her and clutching her against his own chest. Kitty whirled with him as if he’d pulled her by the hair, scrabbling the air and clawing her fingers. A soft word from her father subdued her and she accepted the authority of parenthood, sagging back to the shape of a little girl, contenting herself with accompanying him back to me. Her hand nested around Leila’s ankle and she skipped to keep up, beaming with pride and pleasure.

I took my new-born child and laid her on my chest, nuzzled her face and nudged a nipple towards her mouth. Kitty leant at my side, her hand on my shoulder, whispering a stream of nonsense words to her baby sister. I lay back and groaned with pain and relief and thought two things: Leila really did look like a disgruntled baby crow, and her blind gaze hadn’t once left Kitty’s.

NERVES

We were three years into our marriage when I realised Peter and I weren’t ever going to apply for our passports and spend our lives guiding tourists around the souks of Morocco or running a beachside cafe in Australia. The temporary postponement of the future we’d dreamed about had become a hurdle he couldn’t overcome. He seemed to love his morning milk round and afternoon gardening jobs, while I fidgeted through dull days filing and answering the telephone at a solicitor’s office.

Those long Saturday night conversations planning our getaway, sitting cross-legged on the carpet in a slippery puddle of travel brochures, passing them back and forth, had segued into monthly attempts on my part to rouse his enthusiasm. I cooked Indian feasts from exotic cookery books I’d borrowed from the library, replacing the powdered ingredients I’d never heard of and couldn’t find in the local grocers, with substitutes like allspice and gravy powder that at least looked the same even if the end result didn’t taste at all as I imagined a curry should. I cut out glossy, vibrant photos of seas spangled with plankton or mountains so vast and high the summit was forever snow, sticking them to the side of the fridge so that he’d see them whenever he made a cup of tea.

I haunted the travel agency in town during my lunch breaks, gazing through the window and eavesdropping on conversations between well-heeled couples planning their next foreign trip as they scanned the offers pasted on a board by the door. I was too shy to go inside more than once a month to collect another brochure, and I knew the sourpuss lady who managed the bookings saw me for what I was: a waste of her time.

When Peter cropped his hair so that the pale lobes of his ears finally saw the light of day, I knew that we’d never leave here. ‘It’s so much easier this way,’ he’d say when I complained about how I missed dragging my fingers through its knotted length, discovering a stray leaf or a petal and laying it on his thigh. He might as well have been talking about our lives. Why risk the unknown when it’s so much easier to stay exactly as you are?

I tried once to jolt him from his comfortable, timid apathy, battling with words and thrown glasses one desperate night, raging and mocking but stopping just short of issuing an ultimatum I’d be too proud to pedal back from. He countered with wheedling promises of retirement cruises and annual summer trips to the Lake District, and when his favourite mug caught him square on the cheek he began to cry and told me he hadn’t ever thought I was serious, he’d thought we were just weaving castles in the air, having fun. Isn’t that what we were doing? The occasional, endearing stammer he’d always had chewed his words, stalled them in his mouth, and that more than anything revealed him as a liar.

I would have called him a phony and a coward then, maybe even issued that ultimatum, but he beat me to it. He peered pleadingly up at me, arched over him with my fist raised, shrieking in outrage. His chin crumpled to his chest and he held out a hand. ‘I’m scared, Annie,’ he whispered. ‘I don’t want to go anywhere. I like it here. I’m sorry but I’m just not as brave as you are.’

Maybe my cowardice was a match for his. Maybe some unacknowledged sliver of my heart was secretly grateful to be released from my adventurous hopes and dreams, for I let them go in that moment as completely and easily as if they hadn’t been my steady, joyful comfort since I was a child. If there was to be a choice between travelling and Peter, there could be no competition. He was my love, and in his new-found self-awareness I thought he took on a fragility and a wisdom that had previously been lacking. And besides, there was something stirring in the pocket of my womb. A tiny, quivering bomb that I hadn’t told him about for fear it would explode all our careful plans.

I cradled his hand and sat beside him, let him weep out his shame and relief. ‘You don’t want to leave here?’ I whispered, and he ignored my questioning tone; nodded eagerly, gratefully. ‘You don’t want to leave here,’ I said, louder. I said it again. ‘You don’t want to leave here.’

There would be no more planning, no more brochures, no more experimentation with meals I couldn’t pronounce and neither of us enjoyed.

My acceptance of my life, as it must now be, was brisk and total. I tore down the world map from our bedroom wall, collected my notebooks and those teasing pictures I’d taped around the house, and dropped everything into the dustbin the next morning. I’d spend my lunch breaks on a bench in the park with a sandwich and the bullying ducks from now on, or I’d try to make friends with the girls in my office. I’d continue to work only until I had the baby – a baby would surely tether me to the ground beneath my feet, keep my gaze off the horizon – and then I would become a housewife and devote myself full-time to my family. Just like my mother had.

DOLL FACE

Julian and Elsa were never known by those other, secret names families give their loved ones – I don’t mean abbreviations of their true name, of course they were often Jules and Else – but Kitty was Doll Face from the moment she was born. Her beauty was a shock to everyone who saw her, a source of embarrassed pride for me and Peter – both as average looking as they come and yes, we could see the questions smeared on people’s lips as they studied our faces to find anything to genetically link us to this exquisite yet strangely unnerving perfection. Like a china doll, her hair was spun gold, her skin purest silk, her complexion top of the milk poured over a dish full of strawberries. Even when she filled her nappy to overflowing, even when she raged and howled, a toddler tempest hating the world, she looked like a goddess in miniature acting out the part of a mere human.

When she slept I’d find myself leaning close to capture the trickle of breath leaving her cherry-blossom mouth, just to make sure she was indeed a living creature and not a cleverly constructed mannequin. I’d press her cheek and find myself surprised at the soft, warm yield of flesh; I was on some level expecting the slippery chill of porcelain. Buttoning her into her pyjamas, my fingers would dance along her spine in search of a tiny key. If I’d found one, would I have plucked it from its lock buried between her shoulder blades and hung it round my neck on a chain? Would I have swung it back and forth just out of reach of her cupped, pleading palms and watched her wind slowly down, until she stiffened into stillness and I captured that moment when she simply stopped part-way through a blink? Safe at last.

I was terrified for her, of what the world can do to such extraordinary beauty. Everyone wanted her; to touch her, to be her, to gain a little borrowed grace themselves from closeness to her. And everyone would eventually want to tear that beauty from her, unpeel her like wallpaper strips to see what was underneath, hoping for rot. I had to prepare her for the world’s teeth, turn her away from an empty-headed reliance on looks alone, and I was harsher with her than I needed to be. I don’t regret it, even now; at least I don’t think so. Her allure might have stopped traffic but it didn’t stop the evening’s chores. Emptying the overflowing bin in the kitchen, braving the rats and the stench as she collected eggs from the chicken coop at the end of the garden, those were Doll Face’s responsibilities. I set her spelling tests at weekends and made her recite the times tables, docking a pudding for every incorrect answer.

If she’d ever shown the slightest recognition of her power I’d have chopped her hair to the scalp, made her wear a veil and turned all the mirrors in the house, but she seemed oblivious to how special she was. Julian and Elsa helped there. He was the disdainful older brother who only saw Kitty as a nuisance to be swiped from his path, and poor plain Elsa looked at her sister through eyes of envy and rivalry and taunted her whenever possible; hid her teddies, tried to make her eat the shoe polish, ran faster when they were playing in the garden so that Kitty was always a stride or two behind, arms outstretched, tripping in her wellies, desperate to reach her.

Peter’s enchantment with his second daughter glazed his face whenever she entered the room. The muscles in his cheeks would slacken and slip towards his chin, his bottom lip would collapse and drag his jaw open. This gawkish worship gave me an uncomfortable vision of what he’d look like as an old man. I pictured my future self, shovelling porridge into that idiot grin, using the cuff of my blouse to wipe away the trickling saliva. For Peter, beauty equalled goodness, and one smile from Kitty jerked the invisible leash she held in her dainty hands, brought him to his knees. Sometimes literally. He’d sneak out to help her collect the eggs and carry her back to the house on his shoulders, crawl grimly around the front room with her riding the ache of his spine, applaud every learnt nursery rhyme, hoard every crayoned drawing to marvel at in the evenings while the rest of us watched television. ‘Look, Annie,’ he’d say to me, nudging me with an elbow. ‘What an incredible likeness of Pearl she’s managed.’ I’d glance away from my soap opera and then back, pat his thigh. ‘That’s a horse, Peter, not next door’s dog.’

It was amusing and it was irritating, and it was essentially harmless. Shouldn’t all fathers dote on their little girls?

Of course, he had another little girl, who was souring more with every word of praise, every beaming pat on the head that was snatched from her and bestowed elsewhere. I tried my best to stand before Elsa and shield her from the dazzling searchlight of Peter’s adoration, stop her leaping into it and blinding herself. I spun her round and covered her eyes, swept her off to ballet classes where I watched from the side of the room as she galloped about with the sweet gracelessness of a baby donkey. Her dried pasta shell creations were always attached grittily to the side of the fridge, and I used every one of those garish cardboard bookmarks she cut from cereal boxes and smothered in swirls of paint so thick they never quite dried out. I paid more than one fine to the library for books whose pages were forever damaged by the flaking, oozing royal blues and reds.

EMOTIONAL TROUBLES

Julian as a baby was a fluffy-haired, bright-eyed delight. He slept well, fed well and cried only when he needed something. Once those needs were met, his smile was back before his tears had dried. I really didn’t understand why people complained so much about this parenting business; it was a piece of cake.

My mother relished doling out prophecies of a life spent in perpetual worry, of never sleeping again and never knowing a moment’s peace, until eventually, as the icing on the cake, The Worst Happened – and the worst would happen, mark her words – and then that would be it: ruined lives all round and grief everlasting. Peter’s mother was tepid in her felicitations and vague with her advice so I knew she wasn’t planning to set out her doting-grandmother stall either. But we didn’t feel the lack of this support; caring for Julian was a joy and we vied to bathe him, dress him, cuddle him. I was so relieved to love him as much as I did, to not resent his arrival and the death knell it sounded for that other person I might have been.

When I found out I was pregnant with Elsa I carried the secret of her inside me for weeks, thrilling with the thought of this hidden jewel tucked in my womb. I knew she’d be a girl and I adored her already, day-dreaming frills and bonnets, pigtails and satin bows. Julian would protect and guide her in his role as the perfect older brother and she’d be the indulged apple of Peter’s eye. Who needed foreign adventures when your domestic life was this fulfilling?

Unlike her brother, who’d punched his due date right on the nose and left my body with relative ease – I say relative; the birth had stretched my endurance to its limits – Elsa was six days late and then another two days in the coming. Figuring myself to be an old hand at labour now and wanting as little disruption as possible for Julian, I’d decided to have a home birth. Peter was nervous but willing and so we left Julian with my mother as soon as I felt the first contractions, with breezy assurances that we’d be back for him within the day. We ended up racing to the hospital in an ambulance, me wailing louder than the sirens, after eighteen solid hours of the kind of pain that convinced me I was birthing an axe and not a baby.

When she was finally manipulated out of me by a brisk man wielding scalpel and forceps, one eye on the clock and tobacco breath, I looked down at the mewling chunk of human flesh that had suddenly appeared in my arms, its claret cheeks clashing horribly with its wispy pastel-pink hat, and I felt nothing but a bone-deep sadness. I yearned to reverse this awful mistake and be home with Julian, just the two of us, clapping along to nursery rhymes and chasing kisses along his shoulder blades. But, of course, this was just the traumatic hangover from a difficult birth and the last of the drug fumes filtering through my blood; I’d be fine in a day or two, once I’d had some decent rest and a good wash.

Grimacing apologies at the other mothers when Elsa’s shrieks drilled through the ward, nodding gratefully and handing her over when a nurse offered to take her back to the nursery to give me a break, I pretended a fatigue that I probably did feel but which was buried deep beneath a melancholy so vast I couldn’t fumble a way out of it. I lay awake when I should have been sleeping, consumed with fear that Julian would forget me, that he’d already forgotten me, that when I finally left the hospital he’d toddle past me in reception to some other woman and hand a pink balloon to her. I was bitterly jealous of Peter’s freedom to come and go whenever he pleased and furious with him when he brought flowers, furious with him when he didn’t. I wouldn’t let him bring Julian to visit but pestered him to tell me exactly what my boy was wearing today, which socks, describe them exactly, I don’t know which ones you mean.But he doesn’t even own grey socks with sheep on.

After a week I was allowed home and we all – the poor nurses especially – released a long and heartfelt sigh of relief. Things would be better once I was home. Elsa would start feeding properly and I’d be happier; we’d settle into a routine. I’d start loving her.

She did seem to relax more away from the clanging bustle of the hospital, her solid little body loosening and unfurling, her cries less devastated in pitch though just as frequent. I’d sit on the very edge of the bed through the hours that Peter was at work, watching over her in her crib while Julian bounced on the mattress or trundled his toys across the carpet. She twitched constantly in her sleep, her tiny arms jerking against the blankets I swaddled her with, as if she were trapped inside something; pushing against it to find a way out. When her eyes snapped open her expression was one of vast terror, her mind still tangled in the maze of her nightmare. I’d lean forward and hush her, watch her slacken with relief at the sound of my voice.

I wore thin cotton gloves when I lifted or held her, keeping my skin away from direct contact with hers. I’d read about the importance of touch for new-born babies, how vital skin-to-skin union was, and I knew that, as love transfers itself from mother to baby this way, so too must a lack of love. I had to protect Elsa from the indifference that clung to my flesh like mist. I was frightened it would encase her, soak into her pores and stiffen as lacquer until she was sealed forever inside this loveless space.

Just the thought of nursing her filled me with horror – my sour and tainted milk corroding her insides – and so I didn’t even try once I was home and away from the burden of others’ expectations. Peter fed her from the bottle in the mornings and evenings, urged on by me and enjoying the novelty. I encouraged him to bathe her every day after his milk round while I supervised from across the room with Julian snuggled onto my lap. A full week could go by without me touching her at all, except the occasional accidental brush of fingertips against her legs or stomach when I’d stripped off my gloves to change her. I wiped the stain from her immediately before it could do damage.

I hadn’t realised it would be so easy to live like this. I’d thought I’d have to do a lot more pretending, blow a lot more smoke into people’s eyes, but nobody seemed to notice. We see only what we want to see, I realised. And all anyone really wants to see is a mother caring capably for her child. Short of dangling Elsa by an ankle when I answered the door to the health visitor or leaving her alone on the kitchen floor while I took a bath, I wasn’t ever going to attract concerned looks or tentative questions; there would be no sharpening focus as I patted the air around Elsa time and again but never actually brought my hand down to rest on her body.

It was Julian who rescued me, in the end. Elsa was about eight months old and starting to grab at things, her eyes squint with the effort to keep the prize in sight. We were in the living room, the three of us, on a drizzly autumn afternoon. The television was tuned to Julian’s cartoons and he was sat on the floor in front of it, nose up to the screen, elbows on thighs and transfixed. Elsa was propped on a pile of cushions wedged between my feet. I turned the pages of a community newsletter and gazed out of the window at the dripping fuchsia, idling away the time until Peter would be home and I could start dinner, begin the soothing process of the evening routines and then the blessed comfort of bedtime and sleep.

‘Mummy?’ Julian said, startling me back to the room. I looked over. He was turned on his haunches, facing me and Elsa, who was creeping the last few inches on her belly to reach his side. I hadn’t noticed the shift in weight when she’d rolled from the cushions. We both watched as she flailed and struggled, flipping herself onwards, a baby turtle with Julian as her sea. He was smiling, pleased to be her destination, and he held out his hand when she was close enough to grasp at him so that she clung to his fingers with hers and jackknifed the last inch, landing up against his leg and hanging on.

He hauled her onto his lap and raised her arms above her head, pumping her fists up and down as if she’d achieved something truly victorious, laughing over at me. She flung her head back against his chest, bouncing it off his jumper, squealing with joy and kicking her feet. In that moment it was as if someone had taken a knife to my side, slid it through my ribs and punctured a hole in the poisoned sac that surrounded my heart. I could feel the deflation, feel the sadness and the months of numb fear shrilling out of my mouth in one long cry.

Julian gestured for me to take his sister – he’d lost interest now and wanted to go back to his cartoons – and I slid onto the carpet and crawled towards her on my hands and knees. ‘Clever baby Elsa,’ I said to her, gathering her into my arms and shuffling back to the sofa with her pressed against me. I peeled off the gloves and ran a finger the width of her face, ear to ear, bumping over her nose. ‘Aren’t you the cleverest baby girl there ever was.’ I held her through the rest of the afternoon, snuffling at the back of her neck and cupping her head in my palm while she slept.

I told Peter everything that evening, confessing those months of dulled, deadened dread in a euphoric orgy of self-loathing and redemption. We sat across from each other at the kitchen table and I thrust my gloves onto its surface, flinging them away from me with repulsion, laughing and weeping as I described the joy of finally feeling love for our daughter. He was appalled, both with me and his own blindness. I wanted his anger, I needed to be judged in order to be absolved, but he was more shocked than angry. Shocked at what he saw as a cunning display of deception – I think it made him feel like a naive fool – and shocked at the very thought that a mother might not love her child instinctively and immediately. He watched me with close suspicion and sorrow for some weeks after, alert to any sign that I was less than fulsome in my attention towards either child. Even after Kitty was born and we both relaxed our guard once she was in my arms, and I laid the first besotted kiss on her brow – those new-born months with Elsa now a memory that stung but didn’t lacerate – I knew that he’d never be able to fully forget or forgive this flaw he’d discovered inside me. Some part of him would forever be waiting for it to rear up again, the devastating fault seamed deep in my character, there to destroy our family.

THE MILKMAN’S DAUGHTER

It’s strange, how two fawn-haired people can produce a child with hair as dark as Leila’s. I assumed it would lighten and thin as she passed through the months, but it deepened to a black so thick you could plunge your fingertips into it and fear they would never emerge. It twisted from her scalp so that her pale little face glowed like a spotlight among shadows. The beakish nose cast its own shadow over the purse of her mouth, and I pitied her that.

Peter never said a word, but he’d twirl a lock around his finger as he passed her in her highchair, tugging at it thoughtfully. He flicked dubious looks at the neighbours over the garden fence, and if I opened the bedroom window and leant out at dawn, I could hear the strained whine of his beleaguered milk float stop-starting furiously around the streets. I could almost smell the dusty heat of the overworked batteries glowing beneath the seat of his trousers, as he raced to be home in time to greet the postman at the door and see him off again. His stammer worsened the longer he was in a room with Leila.

If he’d ever said anything directly then I would have cheerfully and categorically reassured him, made that old scathing joke that put the matter to rest, but his reticence, his barely there suspicion, lodged like a stone in my throat and dammed up the words.

Until I left home, I’d never met an adult who’d travelled abroad. My parents’ friends and my friends’ parents, they were all paired off and inching stoically through their days. Apart from a tumultuous and publicly broadcast – in my eyes, glamorous – on/off marriage at number 19, and a living-in-sin at number 48 that was, in my mother’s opinion, proof that Britain had Gone To The Dogs, every grown-up on the estate around me was doing exactly the same thing as the family next door: husband at work – if the household was respectable anyway – wife at home, wearing a grey and pink checked overall, knee-deep in children. Nobody seemed particularly miserable or noticeably joyful; they were just getting on with it. I knew that shackled life wasn’t going to be for me.

When I first met him, Peter wore his hair below his shoulders and smoked grass from a clay pipe he’d made himself. He’d been in trouble with the police once or twice for thieving – ‘That’s all behindme now’ – and the glamour of his criminal record thrilled me. He laboured for a local builder and was going to be a famous songwriter. I was newly severed from home, living with a gang of girls in a dismal block of flats and training to be a secretary, but I was going to be an air hostess. I imagined myself at forty, worldly and childless, dazzling friends at dinner parties with my foreign knowledge and foreign ways. I saw him in the pub at the end of our street, strumming his guitar and gulping beer, and I floated towards him as helplessly as a balloon that needs the firm grasp of a hand to keep it tethered. He was the reflection I saw when I looked in the mirror, the vision of myself that I thought the world saw: averagely pleasant looking, hair and eyes varying shades of mouse, nice smile. We neither of us would turn heads, but we could not turn heads together.

Peter and I married before I’d finished secretarial college. I was exactly the age my mother had been when she married my father. I even wore her old wedding dress. I was determined to complete the course and get my qualification before we left the country to live abroad, because who knew where being a trained secretary might come in useful. Peter could lay bricks and slap plaster onto walls so between us we were going to be fine no matter where we landed up. And we had love on our side; the all-consuming, nobody’s-ever-felt-this-way-before kind.

We were offered a brand-new council house on an estate just far enough away from my parents to make sure family visits were never impromptu. The garden was bigger than my entire childhood home and I could see distant fields from the upstairs toilet. Too good an offer to turn down, so we moved out of our makeshift camp in his mother’s front room and accepted the tenancy. We’d just wait a little longer, save a little more, before we got on that aeroplane. When Peter swapped his labouring job for a milkman’s round he’d take me out on deliveries, swinging around the potholes while I perched in the back of the float clinging to the crates of pop and juice, dangling my feet inches above the rushing tarmac and losing sandals at least once a week.

Then we had Julian and I never stopped finding the hilarity in telling people proudly, as I folded down the hood of his pram outside shops, that he was the milkman’s child. That momentary expression of confusion or shock, the glance up at me, or at Peter grinning and nodding beside me, gave me such a silly glow. ‘Yes, ten weeks old today,’ I’d say to the woman on the bus. ‘He’s the milkman’s son. He looks just like him.’ Then I’d raise a finger to my pursed lips – Don’t tell – and turn back to the window.

The joke had staled by the point Kitty was born, or there was simply no time anymore for joking around and playing games. It was probably a good thing it was buried by then, for that initial, insulting incomprehension when people took a look at her perfect face and then at us, would have been swiftly replaced by a sly, equally insulting belief in my words and then a rush home to ring around the milk suppliers.

But when Leila was born and I saw those moments of frowning thought when Peter watched her, the bemusement and worry, I remembered the old joke and knew he did too. Not so funny now.

NIGHTS

Kitty pined for her younger sister every moment she was away from her. She had to be close to her all the time when she was home and she kept a snip of curl in the pocket of her dress for when she was at school. If I woke in the night and leant over to check on my baby, I’d find the cot empty as often as not, the blankets an untidy heap at the bottom of the mattress. The first time that happened I panicked and woke the house, plunging through a shriek of terror from room to room and downstairs, back up again, until Peter caught me round the waist and steered me over to our bed, shooing the children back to their dreams. ‘Look,’ he said, pointing at the cradle set up on the rug by my pillow. ‘It was just a nightmare. There she is.’

I stared down at the ghost face of my sleeping Leila floating among its wreath of curls, and then spun into the children’s room. My fury left sparks fizzing in my wake. Kitty was lying curled on her side, sleepily awake, and she smiled at me when I leant over her.

‘Don’t you dare do that again,’ I warned her. ‘Don’t you dare take her from her cot.’ She frowned and nipped her lip, the picture of confusion. ‘But I didn’t, Mummy. I woke up and she was with me in bed. I put her straight back, I promise.’

The next morning I kept Leila on my hip as I made breakfast. I wouldn’t let Kitty hold her. The two gazed miserably at each other around the cage of my arms, reaching out to brush fingertips before I snatched Leila back and settled her to weep against my shoulder. ‘Dishonest little girls aren’t allowed treats,’ I told Kitty, ‘so you‘re not having a chocolate biscuit in your lunch box today.’

She didn’t seem to care. Over the months that followed she didn’t stop her night-time theft of her sister, though I never managed to catch her in the act, no matter how hard I tried to stay awake. I’d go and stand beside Kitty’s bed before dawn sometimes and watch the two of them sleeping: Leila sprawled safely inside the careful boundary of Kitty’s embrace, both pearly from the just-light that touched them, both smiling.

JEALOUSY

What kind of mother is jealous of her own child? The more Leila yearned for Kitty, the more I needed that exclusive love I’d taken for granted as my due with all of the other children. I breastfed her for far longer than I had any of the others, until she herself decided it was time to move on to something more substantial and reared away from me, leaping from my lap whenever I picked her up and unbuttoned my blouse. I dipped strawberries in honey and then into her mouth. I read her stories when I should have been helping the older ones with their homework. I dropped her at nursery but didn’t go straight home, scuffing instead through the undergrowth by the side gate, hopping and waving to get her attention when she sprang into the yard with her classmates.