Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Fern's choices in life and in love are an echo of her mother's, as Iris' are an echo of her own mother's. Three women, three generations: one dark secret. Iris keeps a scrapbook of Lawrence, the lover who went missing years earlier. Fern's father. She defines herself by his loss and soothes herself with gin and the fairytale of this one perfect relationship... Fern, once a 'strange and difficult child' who believed that her dead grandmother's soul lived inside her stomach, reluctantly returns home to the island to take care of Iris. She is tasked with finding Lawrence and in the process she has to confront her own past and memories... Ivy, Iris' mother, had her own cache of secrets; spells she took to the grave. Spells that Fern unearths. The Scrapbook is a novel about memory, and the unreliability of memory. It's about the tangled, often dysfunctional, bonds of family. And it's about absence and the power that a void can exert over a person's life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 311

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Variation On A Love Spell

1

A Torn Scrap Of Dark Blue Handkerchief

2

A Clipped Square From The Top Of A Cigarette Box

3

A Bird’s Claw

4

A Blood Soaked Shoe Lace

5

A Dried Fern Leaf

6

A Pebble Shaped Like A Heart.

7

A Tarnished Silver Chain

8

A Creased Page From A Map Book, With A Wooded Area Ringed In Red

9

Two Photographs Of A Man Asleep

10

A Page From A Calendar (showing two months)

Acknowledgements

Advertisement

Copyright

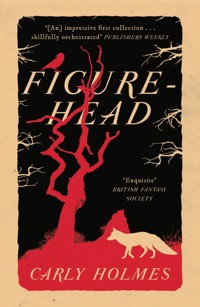

The Scrapbook

Carly Holmes

For my lost ones: Luna, Goblin, Moomin

Variation On A Love Spell

Take in your cupped palms

two flaming pieces of fire opal

and two gentling pieces of rose quartz.

Linger a while with sweet thoughts.

Lash each crystal to your chest with a plait of red silk

lined above your heart’s beat

and leave them for five days and nights.

Never allow so much as a sliver of breath to separate them from the warmth and touch of your flesh.

Glaze these crystals with your body’s sweat.

Paint loving pictures in your mind’s eye.

Rise to meet each morning with harmony

and greet your pillow each night with desire.

On the sixth day remove one of each crystal but leave its twin on your skin. While they are still warm from your heart, still wet from your ardour

gift the removed crystals to your lover.

They must be kept as close to your lover’s skin as possible.

If this spell is surreptitiously cast then use your wiles to secrete the crystals

where their magics can be felt but not found.

After three days and nights the fire you lit in another’s soul will spark

and you will know the heat of true devotion.

The stronger your longings,

The stronger the charge,

The stronger the love.

Take care to never lose the crystals after they have secured your desire.

Keep all four safely wrapped up together where no harm can come to them.

If you wish for your shared love to transcend mortality then ensure that you are both buried with your crystals.

It matters little by this stage whose were originally whose.

Be sure and be true to your love for evermore.

A certain manipulation of their original fate will be your cross to bear.

1

I was four the first time I attacked my father. My memory of it is sulking behind twenty-odd years of bicycle tumbles and birthday parties, first kisses and fierce heartbreaks, and so I only have my mum’s account to rely on. Depending on her mood, and how much she’s had to drink, I’m either painted as a strange, difficult child (buoyant, first gin), or an out and out child of Satan, practically gnashing my teeth and straining towards people’s throats (weepy, finishing that one too many).

Such an angry little girl… So embarrassing… I couldn’t take you anywhere…

The fragments I do recall are the smell of sun-scorched leaves and the back of my mum’s head. She stood by the window in the front room and shivered from foot to foot, releasing layers of fruity scent with each warm tremble of excitement. Even now, if I dip my face into a bowl of peaches I feel bereft, just for a second.

I knelt behind her and itched to touch my clammy fingers to the filmy hem of her dress. It must have been summertime.

Granny Ivy sat hunched like a raven in a rainstorm and stabbed thick thread violently through one of my dresses, sewing a pocket onto it. She muttered constantly to herself, occasionally pausing to peer at me or to press a thin finger against the dark, cracked book she always kept by her side until the day it disappeared. HerCooking Book, she called it, which always made mum snort.

The only ingredients you’ve got in there are toad’s eyeballs and hen’s claws.

So, mum stood, and shivered, and glanced over her shoulder but didn’t shift from her vigil.

Fern, stop staring at me… Fern, get up off the floor…

And then she was gone. I blinked and looked away, as instructed, and movement tangled suddenly in the corner of my eye. The front door was wide open and I could still smell her, but she’d disappeared. I leaned over and looked for the puff of smoke, straining after her absence even as she returned, smiling and joyful.

Lawrence is here. I’m off now.

She stood in the centre of the room as if she’d never left it and tapped her feet and crossed her arms. I shuffled backwards, away from those mean looking high heels.

Don’t wait up.

Granny Ivy hissed and jerked and the needle slipped deep into her palm. She and mum stared at each other and I watched the blood drip over the brand new pocket of my dress. I’d chosen the pocket myself from old curtain material and I wanted to point at the rusty stain as it ruined the beautiful pink cabbage roses, wanted to shout something at them both to break their concentration. But then a man walked into the room and straight up to me. I hadn’t heard a knock at the door.

Hello, Fern.

Mum snapped out of her hard face and into her soft one. She took the man’s arm and hugged it to her.

Fern, say hello.

I looked at this man being held by my mother. I glanced over at Granny Ivy, then back.

Who are you?

There was silence. Then Granny Ivy sniggered and shot me a look that meant there’d be biscuits before bedtime. Mum laughed brightly, for too long. She bent down and showed me her hard face again, just for a second, just for me.

He’s your father. Now stop being silly and say hello.

She straightened up and laughed again, turned to the man with a shrug of hopeless mirth. He grimaced at her and crouched down next to me, legs creaking inside soft grey cloth. I imagined wooden knee joints and wondered if he was a puppet. A huge hand descended onto my head, pressed my hairgrips into my scalp and hurt me. I wriggled and tried to duck away but couldn’t slip out from under his palm.

Hello, Fern.

Mum scooped up her handbag and glanced at her watch.

Say hello to your father, Fern… Fern, say hello…

I dived forward to escape them both and then flung myself onto his chest. Thrust upwards as high and as hard as I could, as if I was a swimmer and he was the water. I grabbed a handful of his hair in each fist. And I pulled.

It took them ages to uncurl my hands and drag me off him. By the time they’d managed it the man was scarlet and breathing noisily through his mouth and my mother was white and stiff. I scuttled to hide under Granny Ivy’s long skirt, clutching strands of oily, mousy coloured hair. The man smoothed the front of his jacket, tried to smile, and turned away.

I’ll be in the car, Iris.

He hadn’t looked at Granny Ivy once in the whole time he’d been inside her home, and she hadn’t looked at him.

My mother rushed to follow, pausing to point a finger at the bulge I made under my granny’s chair. She mouthed speechless outrage and jabbed the air with menace.

After they’d gone – and this I remember very clearly – Granny Ivy gently removed all of the strands of the man’s hair from my hands, untwisted them from my fingers and inspected my palms for any stragglers. Then she tucked the greasy bundle inside the cover of herCooking Bookand patted my back.

Good girl…Don’t cry…

I followed the midnight billow of her skirts through to the kitchen and wondered if she was going to leave the hairs out on the sill for the birds to take away for their nests. I watched her to see if she would but then she placed a tin of biscuits down in front of me – the whole tin – and I was distracted for a while. We sat at the table and I crunched through bitter chocolate and fierce ginger while she watched me and smiled. She brewed tea and then opened her book, flickering through the pages as I reached for another biscuit, and then another. I wondered what she’d be making for supper.

Granny Ivy caught my wrist as it dived once more into the tin. She ran a nail along the knobbled warts that bumped a line down my middle finger. I sat with a biscuit in each fist and another in my cheek and listened as she began to speak.

Search and you will find

a large, smooth sprout

hanging low upon the stalk,

defying the helix,

and paler than its mates.

This is the one.

Sharpen your knife

and slice.

Two halves. Two wrinkled hearts.

Press firm and hard this wrinkled heart of one half onto the wart.

Press, and count the minutes down from five to one.

Rejoin the halves and bind with string

and bury beside an oak tree.

The sprout now an oyster beneath the earth

cradling your wart in its rotting heart.

Remember not to ever dig around this buried vessel

or expose it to sunlight

or skin

as the wart will sense its kin

and cleave with you once more.

She continued to mutter as she stood up and fetched her sharp, wooden-handled knife from the cutlery drawer. I sneaked another biscuit and went to the window to watch as she prowled around the vegetable patch, bending, straightening, shaking her head and bending again.

It was only later, years later, I realised that herCooking Bookwasn’t a recipe book in the strictest sense. At the time, as I listened to her words, I felt only disappointment that we’d be having sprouts for supper.

When mum returned, much later, I was awake in our room and my tummy hurt. I’d been whispering my secrets to the oak tree that loitered outside the window but when I heard her open the door I burrowed under the blankets and closed my eyes. She smelt different now, the fruity scent gone and replaced by an odour that was musky and pungent.

I snatched a peek as she climbed over me to get into bed and saw how swollen her lips were, as if she’d put too much of her red lipstick on without a mirror’s guidance. Her neck was a swirl of blotches and she was smiling to herself. She looked happy.

I’ve borrowed the bones of my mother’s recollections and fleshed them out with my own. Are they true? I can remember how mum smelt, both before and after her assignation with my father, and I remember the sting of his hair cutting into the flesh of my hands as I held on for dear life and for Granny Ivy. But was it real?

Because, you see, I can also remember screaming, spinning across the bedroom when I was about six as a spider thrashed around in the knots of my hair. And that didn’t actually happen, according to mum. Well, it did happen, but to her when she was a child, not to me. She’d told me about it and I’d internalised the incident and made it my own. Memory’s a trickster like that, isn’t it? We all have a habit of rewriting our histories, donning and shedding layers as it suits us and believing every version. I’m no different, so consider yourself warned.

I was nine when my father disappeared, never to be heard of again. I attacked him twice more in the intervening five years, or so I’m told.

One of those times was at a picnic. Allegedly. I’m slightly dubious about this one as I don’t remember a thing. Not even a smell. According to mum she’d spent ages persuading Lawrence to give me another chance and so we all went on a picnic, like a proper family. Jolly decent of him. He passed me a sandwich and I leaned in and bit his hand with my sharp little teeth. I growled. He had to have a tetanus shot.

Five stitches. He had to have five bloody stitches!

The other time I do remember but that doesn’t make it true. He was stood at the front gate, waiting, while my mum hurled herself around the bathroom with hairbrush and mascara. His car filled the lane and was the colour of cherries a day before they’ve reached their peak. I wanted to pat the bonnet but didn’t want to speak to him. I started to trot down the path, pretending to be a horse, and then broke into a canter and then a full-on gallop. Beds of forget-me-nots collided into one solid blur of colour as I raced down the path and prepared to jump the hurdle. Was I trying to skip past him and get to the car? Who knows? Either way, no matter how pure my intentions, I whinnied and butted him square in the stomach and he folded in half and clung to me to avoid falling over. His breath against my cheek thick and wet with pain.

After that he didn’t even get out of the car when he came to collect my mum. He just hit the horn and kept the engine running. Sometimes his gaze would find mine as I peeped from the kitchen window, and he’d nod and raise a hand. I’d nod back and show those sharp little teeth in a grin and he’d lower his hand to his lap and look away. I knew then that he’d be massaging the scar I’d given him and the car’s interior would echo with the battle cry that I’d shrieked into his stomach.

Has my mother ever forgiven me for his disappearance? Is there a chance she ever will? I know there are times when she blames me entirely for it.

Those times when she doesn’t speak are the worst.

Every day since my return to the island, I see her strain towards the window, lumber from foot to foot until she gets too tired to stand, her varicose veins pushing through her tights like a nest of slow-worms, and I want to kneel behind her on the rug and see her as she used to be. My young, beautiful mother, in her gauzy dresses and her ridiculous heels. My magical mother, who could disappear without even needing a puff of smoke.

She refuses to move from this house. Even after Granny Ivy died and left behind plump pensions and insurance policies, she wouldn’t even book a week’s holiday to the mainland. You see, she believes he will come back for her. Just like old times. He’ll appear in the lane in his magnificent motorcar and she’ll lift up her skirts and run to him.

She knows that there are such things as telephone directories and he could track her down if he wanted to, but deep inside her, flailing for air beneath the hope and the gin, is the belief that if she made it too hard for him then he just wouldn’t bother. She needs to stay right here, right where he can find her without any effort.

What he’d make of me being here as well I can only imagine. The poor sod, to finally return after an absence of seventeen years, certain that, by now, I mustsurelyhave gone. Only to find me once more narrowing my eyes at him over the threshold as I help mum up from her chair and out of her slippers.

I wouldn’t be here at all if she hadn’t needed me. I did actually leave Spur and was making a fairly decent stab at adulthood all by myself on the mainland when she called me back. Or rather Tommy did. He’d dropped by with some eggs and found her at the bottom of the stairs, twisted and spiky with broken bones. She’d been lying there for most of the afternoon, inching a tortured route across the hallway. Tommy thinks she’d been trying to reach the phone but I reckon it was more likely the bottle of gin on the dresser in the kitchen.

When he phoned from the hospital with his catalogue of injuries– concussion, broken wrist and elbow. Cracked ribs as well. She can’t manage by herself, love, you need to be with her–I asked for time off from the cafe and agreed to come home. Just for a while, just until she could be safely left alone. It didn’t take long to pack a bag and put all the plants out in the back garden to fend for themselves. The rent was taken care of for the next month and thanks to Granny Ivy I had savings to fall back on. There was nothing else to stop me. And once I’d committed I suddenly yearned for that sense of snugness only living on the island had ever given me. Swaddled by sea on all sides, safe.

To be honest I wanted to see her again, spend some time with her. Maybe even ask some questions. I’ve become sentimental lately, preoccupied with the past. I want to pick through that collision of gristle and genes that links the generations, try to make some sense of it. And that means I’ll need to know something about him. My father.

I’ve spent my life refusing all knowledge of him, as if I could somehow be tainted by the familiarity. I don’t even have a clear memory of what he looked like anymore because there are no photographs of him. It’s only lately that I’ve come to accept, though grudgingly, that he had just as much to do with forming the person I am as my mother did.

We’re doing okay actually. Me and mum. Since my return she’s discovered gratitude and a sense of humour, and so we laugh a lot. It’s generally barbed laughter, and at the other’s expense, but that’s how we both are.

Or how we’ve become.

*

Today she’s indulging one of her bad, sad moods and she got at the gin while I was out watching the morning ferry from the mainland come into harbour. We have a rule that generally works: I won’t try to stop her drinking and she won’t try to pour it down her throat before dinnertime. I cheat a little, I have to confess, because I keep all of the alcohol on the top shelf of the kitchen cupboard so she’d be hard pushed to reach it without my saying so, and I can’t see her scaling the cabinets unaided. But this morning she outmanoeuvred me somehow. Maybe after lunch I’ll slick the kitchen counters with olive oil or tie her to her chair while she’s sleeping it off.

‘Oh, Fern, I still can’t believe he just upped and left us,’ she whispers to me as I try to wrestle the glass from her. She’s as devastated as ever she was, and I’m a little in awe of a love so splintering that it can still hurt her this much. I give her a hug and then twist the glass out of her grasp. She lunges for it, arm flapping in its sling, and I drink down the contents quickly. Wince at the strength of the barely-mixed spirit.

‘Gone. And no more until dinner. Remember your promise, mum.’

As I turn to leave she kicks out with a bloated foot and catches me on the ankle. I almost laugh despite the sting of it. ‘Hey. That bloody hurt.’

‘It’s all your fault. You ruined everything. You and your bloody grandmother. You never wanted me to be happy.’

She tries to heave herself out of her chair but alcohol and anguish conspire to turn her bones to rubber. I hover a wary couple of feet away and watch her struggle and my irritation bleeds into pity. Again. But I won’t move any closer, not just yet. She hasn’t exhausted the limit of her pain and anger.

‘You drove him away, with your nasty, spiteful temper. I thought we could be a family. Once I had you I thought it would all be different. And maybe it would have been if you’d only behaved like a proper daughter, given him a reason to want to come back.’

I cradle the glass to my chest and try to remember how fragile she is. Try to remember that this is not forever. Then I put the glass down.

‘You weren’t exactly a great mother, if memory serves.’

She swipes at me again, carves a shaky path through the dust motes dawdling in the sunlight. I laugh with bitter pleasure and dance backwards. ‘Missed.’

Mum grunts and hunches on the edge of her chair, swaying. She looks as if she’s about to topple right off it. ‘I did my best. But you were impossible. Couldn’t be trusted to behave like a normal little girl. And as for your grandmother…’

I pick up the glass and turn to go. ‘Leave her alone. She practically raised me.’

Her voice rises. ‘You were nothing but her puppet. You know she was a witch. She used you to break us up. Turned you feral every time he came near you.’

Sweat studs her upper lip and her cheeks are purpled with distress.

‘What can I say to that, mum? Apart from … Oh no, it’s come back. The feral beast has come back.’

I claw the air and contort my face, wiggle my tongue at her. After a second’s prim silence she titters grudgingly and flaps her good hand at me. ‘Don’t mock me, Fern.’

I lean over her and kiss her damp forehead. ‘As if I ever would.’

As I butter bread in the kitchen I can feel the delicate change of pressure in the house that means she’s either asleep or groping towards it. I sit at the table and eat her share of sandwiches as well as mine, look around me at the room. Each mark and stain tags a memory. The cracked tiles by the cooker are twenty years old, but the look on Granny Ivy’s face when she dropped her stew pot after I’d crept up on her makes me shiver even now. That burnt patch on the work surface is still livid, a perfect circle scorched into the wood by the bottom of a pan when mum tried to fry eggs and drink gin at the same time. This house is as familiar to me as the inside of my own skull.

The phone starts to ring as I’m washing up and I jump and drop my plate into the sink, creating a wave that splashes over the side and onto my jeans. I’ll never get used to the presence of a telephone in this house. As I wipe my hands dry I try to remember exactly when mum got it. It can’t have been that long before I left home. Now when the phone sounds she doesn’t even bother to answer it. She’d surrendered her fantasies when she had it installed, had probably known then that taking an active step towards embracing her life would only highlight its inadequacies. It’s far safer to be passive, to wait at the window and hope. Against her better judgement and therules she lived her life by, she let the phone intrude on this and then she sat and watched it day after day, scooping it up occasionally to check the dial tone, before finally accepting that though it may ring, it would never ring for her.

I prod mum awake in the late afternoon and refuse to let her have any more to drink until she’s eaten some soup. The television distracts her from her sulk and she spoons up her meal while she watches the early news bulletin and tuts gloomily at the sorry state of the world beyond her front door. She pats the faded velvet of her armchair with each fresh piece of news, as if to congratulate herself on her good sense in having narrowed her existence to this handful of rooms.

‘Silly man,’ she says to herself. ‘Wearing that tie with those trousers. Lawrence would never do that. He’s never anything but smartly dressed.’

Then she flinches as she remembers and stares down into her soup, using her spoon to swirl the liquid around the bowl.

As I pull her out of her chair to walk the obligatory post-meal lap of the room, she reaches to stroke my hair.

‘Are you okay, love?’ she asks. ‘You look sad.’

Her concern leaves me speechless. I’m not used to such sensitivity from her. Sarcasm deserts me momentarily so I rush out of the room with her stained napkin and run it under the taps, lean over the sink and watch it darken and shift beneath the push of the water. Something about my stance, or the gape of the plughole, makes me want to retch and I abandon the cloth and return to the living room with two big tumblers.

Mum’s back in her chair and I suspect that she cut corners on her circuit. Probably did a quick shuffle on the spot and called it quits. The television has been switched off and she’s sitting with her hands folded in her lap, watching the door. I pass her one of the glasses and watch as she takes a greedy gulp then scowls at me.

‘Very bloody funny. This is soda water.’

‘Oops, sorry.’ I swap her glass for mine and smirk as she sips at it cautiously, then more deeply. ‘That better?’

‘Much better. Bit too much tonic for my liking but I won’t complain.’

‘Well, amen to that small mercy.’ I raise my glass to her and she smiles. She looks lovely for a second, but then she puckers her lips for another go at her drink.

‘You always were cheeky,’ she observes. ‘From the moment you could speak, always so quick with the backchat and the sarcasm. I worried that you’d never get a man to warm to you, you were that prickly. And it looks like I was right.’

She studies me expectantly. I gaze at the wall and open my mouth as if to speak, then shut it again. I can feel her rising frustration and when she starts to huff I laugh and respond.

‘Okay, mum, what do you want to know? Did I ever manage to attract a man? But what if I’m not interested in men, did you ever think of that?’

She looks so confused I want to take it back. It’s easy to forget how insular, how innocent, she can be. I rush to fill the silence before she asks me to clarify.

‘You want to know if there have been men? Yes, mum, of course there have. I remember a particularly nice one called Mark in my first term at university, and an absolute bastard who two-timed me in my final year. He lasted longer than he should have done, but he was fun in a way. And there’ve been lots since then, just please don’t ask me to do a head count.’

She still looks confused. ‘But, Fern, weren’t any of them special? Don’t you want to get married?’

I roll my eyes at her but she’s got her nose buried in her glass and doesn’t see.

‘I’m not like you, mum. You mated for life, but that sort of ‘always and forever, till the end of time’ stuff doesn’t sit well on some people. It can make them twitchy. It can make them leave.’

Her response is immediate and reflexive, her loyalty as touching as it is misplaced.

‘Don’t speak about your father like that.’

She takes another gulp at her gin to soothe herself. I cast around to change the subject and am about to speak when she continues. ‘You know, there’s nothing wrong with true love, Fern. It shouldn’t scare you. Do you have someone special right now?’

She brightens immediately at my hesitation. ‘Ooh, you have as well. Tell me about him. What’s his name? How long have you been seeing him? What does he do?’

I can’t help but grin at her excitement. ‘His name’s Rick and we’ve been together a while. But I’m not taking it too seriously.’ I look away from her, to the clock above the mantle. The evening ferry will be docking soon.

‘Why not?’ she asks. ‘Rick’s a lovely name. I’m sure he’s lovely. Maybe he’s the one? The one that’ll get you to settle down.’

I shift against the lumpy cushions and hiss breath through my teeth. ‘For god’s sake, I’m notlike you, mum. I’m not.’

I don’t know who’s getting more uptight here. She frowns but looks almost smug as she wriggles in her chair and finishes her drink. ‘It’s in your genes, love. There’s nothing you can do about it.’

She hands me her glass for a refill. ‘So. Tell me everything about him. Why don’t you invite him to stay here with us one weekend? I think I’d like to meet this Rick.’

I stand and tilt my head towards the window, my body tense as if I’m listening to or seeing something denied to her. And she immediately swivels and strains, and forgets.

‘What? What is it? Is it a car? Is it stopping?’

Cruel, I know, but it works every time.

A Torn Scrap OfDark Blue Handkerchief

When I first saw you, I had the sun in my eyes. You shone around the edges, a fireball of a man. In the moments it took me to focus on your centre, I’d absorbed you completely. My pores plugged by your smile. You made me shy.

You watched me dance, wild and uncoordinated and my hair vivid with sweat, and you fell in love with me instantly, knelt at my feet and pressed your handkerchief to my scratched knees as gently as you would later press your lips there.

I remade myself in tune to your blinks, your frowns, your glances away from me and then back. I read your needs as they soared across your face, and I carved myself anew again and again, hacking at the rough clay of my personality and re-sculpting, re-forming, without you even needing to speak.

I became like one of those tiny ballerinas who unfold from the raised lid of a jewellery box and perform for as long as needed. Do you ever wonder what happens to them once the lid is closed? Do they continue to swoop and swirl? Limbs gliding through the cramped space below the polished wood. Eyes wide and searching for the cracks that will bring the light. Buried alive.

You believed that we were special, set apart from other lovers, and I took it upon myself to ensure that we never had that moment. That moment when two people in love suddenly seeeach other, without the twin deceits of passion and hope obscuring the view, and they falter and move on but are never quite the same.

Think of a pressed flower between the pages of a book; it’s still recognisable, it looks like what it is, but it’s lost the freshness, the essence that once it had. You still keep it, it still triggers the fond memories that led to its capture and crush, but it’s no longer the perfect thing it was.

It’s the same with love. I never thought to ask what our future would be. Never thought to establish whether you would take me away from this island and introduce me to the world I’d been waiting my whole life to meet. I thought that would be obvious.

You thought your intention, to keep what we had away from the complications of your life, keep me pure, was just as obvious, and so we never talked about any of it until it was too late.

My breakfast splashed around the toilet bowl. My womb no longer a hollow den.

Do you remember those nights when you stretched out on your stomach on the grass beneath the oak and I tapped out tunes up and down your spine? You guessed wrong every time. Every time. Do you remember that?

2

I was ten the first time my mum went away ‘for a break’ and came back with a grimace so vague and so permanently fixed that it didn’t slip even when she was asleep. I still see shades of it now, just occasionally, when she’s overtired or overwrought. Violet creases chase each other around her mouth as her face corrugates and sinks. I hate it. I turn away and start to hum silly little childish tunes.

Every night, I’d lie in the bed we shared and curl up as far from her as I could get, terrified of that bland sadness and the emptiness behind it. Knowing that if I turned around and peered through the darkness, I’d see the glisten of moonlight reflected in her staring eyes. I started having nightmares.

Men with wolves’ heads and red wellington boots pursued me through deserted streets. My mum’s face high among the stars called for me to fly up to her, only I couldn’t get my feet to leave the ground. A runaway car with no driver tipped me off the edge of the world, hurtling me through layers of nothingness.

I began to wet the bed, waking the next day chilled and ashamed. Mum would yawn and roll into the damp sheets, hands pressed hard against her flickering, wayward eyelids.

What time is it, Fern? It can’t be morning already. Wake me in an hour.

Granny Ivy agreed to let me have the tiny spare bedroom, the one Grandfather Edgar had died in. I whimpered and weighed the options and concluded that the dead would haunt me less than the living. I washed the sheets through three times to get rid of any ghostly traces and then moved out of the room that had been my mum’s since she was a child, and into my first proper bedroom.

And the bed-wetting stopped.

I saved my pocket money and took a bus into town to buy yellow paint from Woolworth’s. How impressed my mum would be when she heard I’d caught a bus all by myself. But the paint was too thin, the walls too vast, and the old green bled through the delicate primrose like nicotine-stained handprints. I cut pictures of kittens and cute dormice from school friend’s magazines to cover the ugly blotches, and delighted in the shiny jostle of colour.

I missed the scratch and sigh of the old oak tree waving its branches at me, the whisper of its leaves, but I loved my new pink curtains, made from one of mum’s cast-off dresses. They did nothing to block the light but they quivered in the breeze as if they were dancing with the window frames.

I wanted mum to notice my absence. Maybe even miss the warmth and wriggle of my body next to hers in the night, but she never commented on it. At bedtime, when Granny Ivy looked pointedly from the mantelpiece clock to me and put her sewing aside, I’d haul myself to my feet, trail schoolwork and sighs, and fuss over my night time routine. Satchel left packed and ready by the back door, teeth cleaned, clothes neatly folded, and then a return to the front room for goodnight kisses. Waiting for some words of acknowledgement to accompany the scouring-pad scrape of mum’s chapped lips against my forehead.

Haven’t you grown up, Fern, such a big girl in your very own bedroom!

Always waiting.

Sometimes, when I couldn’t sleep, I’d slide out of bed and tiptoe down the hall. As quiet as a cloud past Granny Ivy’s closed bedroom door, and then into mum’s room. She’d be lying in the scribble of shadows the oak tree conjured in the moonlight and threw across the bed. She never remembered to shut her curtains anymore. Her window wide open, even on the coldest nights. Sometimes she’d shiver uncontrollably in her sleep. I’d struggle with the old wood, try to shut the night out, and sometimes slip into bed beside her to warm her up. I never fell asleep but would wait until she unfolded with the heat I wrapped her in and then I’d tuck her up, covers pulled to her chin, and tiptoe back to my room.