Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

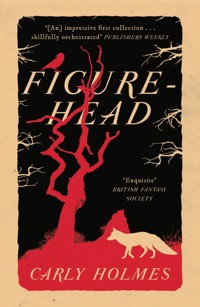

'(An) impressive first collection ... skilfully orchestrated' – Publishers Weekly "starred" review 'This truly is quality literature of our modern times' – The British Fantasy Society 'To read Carly Holmes is to be enchanted. Luscious, flowing prose that is never afraid to peer into the wild' – Angela Readman Beneath her soft skin covering, my mother was once made of twigs and branches. Sometimes in the autumn I swear there was a gleam of berry in her eye, a sloe-shine peep between the thorny tangle of her lashes. In this debut collection of stories Carly Holmes peers into every corner of the strange fiction genre: from rural gothic through to traditional ghost stories and the uncanny. Mothers turn into trees when the sun goes down; Russian Dolls mourn their missing sisters in rotting houses; men offer sacrifices to the monsters who embody their inner wildness; and murderous demons protect young girls' virginity. Ranging from flash fiction to novelette, these stories are in turn chilling, playful, and melancholy. The bonds of family and of community, both in their fracturing and their healing states, the uneasy relationship between living in the present and yearning for the past, are themes that thread their way through Figurehead. Every tale is rich with landscapes haunted by loss and longing.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 410

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

THE DEMON L

MISS LUNA

LITTLE MATRONS

SLEEP

GHOST STORY

DROPPED STITCHES

LIKE WATER THROUGH FINGERS

MARIA’S SILENCE

PIECE BY PIECE

THE GLAMOUR

WICH

THREE FOR A GIRL

PERSPECTIVES

RUNTY

INTO THE WOODS

ALTER

BEFORE THE FAIRYTALE

NEXT DOOR’S DOG

HEARTWOOD

FIGUREHEAD

THEY TELL ME

WOODSIDE CLOSE

A SMALL LIFE

TATTLETALE

BENEATH THE SKIN

ROOTLESS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ADVERTISEMENTS 1

ADVERTISEMENTS 2

COPYRIGHT

FIGUREHEAD

Carly Holmes

For Kelvin

Best, and most infuriating, brother

THE DEMON L

I was thirteen and a half the first time I killed a man. It was an accident and I was dreadfully sorry about it at the time. L, I was called. It was spelled with more letters than that, but L is what it sounded like.

I’d lived a childhood pretty as a picture, even if I say so myself. Of course, we didn’t have a looking glass in our home so I only had the gasps of grownups and ghosted glimpses of my reflection in shop windows to go on, but both gave me more than enough reason to preen.

My mother’s own looks had rotted into Hag over the years and she blamed me entirely for that. ‘I was a raving beauty in my day,’ she told me over and over, ‘and then along you came and sucked the looks right out of me, swallowing them down with the milk that kept you alive.’ The role of crone suited her though, and I could tell she liked it: the shreds of black cloth she tied to her hat and the stick she used to jab my posture back to grace or swipe at any man who tried to touch me without showing silver.

From the age of nine I earned our money and atoned for my thieving beauty by standing in the very centre of the busiest square in the town with a tray of lavender and rose petals stolen from graves and gardens. She squatted behind me, stick at the ready, keeping an eye both on my sales technique (smiles for the men, tears for the ladies) and the seemingly helpless hands that de-gloved and fluttered like weary birds to rest against my face or neck. ‘Stroking is extra. She’s got her complexion to think about,’ she’d shout at the men, rich or poor. But the women she let pat and pinch my cheeks, coo at my long ringlets, while she sniffed and ducked her head with modest pride.

The days were long, especially in the winter. The dried flowers then were scentless and shrivelled by frost, blotched with decay. My feet grew blue and numb inside my boots. But no matter the cold and the poor quality of the goods on offer there were always customers and we never went home laden with anything other than coins and an empty tray. My regulars were permitted past the sharp point of Mother’s stick to allow me to fasten their daily posy to their suit, bending over me and offering their throats while their breath gasped wet and rapid against my face. I pinned the brittle folds of dead blossoms to them and shifted beneath the urgent fumble and press of their gaze. ‘Lovely,’ I’d tell them. ‘Don’t you look fine!’ And I’d accept my payment and the brief clasp of their fingers against mine, smiling just enough to keep them coming back.

When I was twelve, I began to bleed from my core. My looks mutated from angel to demon overnight. Gone was the glassy ethereality of my childhood beauty: that untouched quality that in turn forbade any but the most innocent of touching. Now my flesh curved and plumped in places that drew only the men’s eyes; the ladies averted theirs and stepped around me as if direct contact would contaminate. When I pinned flowers to collars the men shuddered as though condemned to the gallows for a crime they didn’t commit; they muttered words like Damnation and Devil’s Daughter, glaring at me with greedy desperation and lingering to stare even after they’d paid.

Glancing at me over the piles of coins she was counting at the table one evening, my mother did a double take and then nodded wisely. ‘You’ve outgrown flowers, my girl,’ she said. ‘Still a little too young for the stage, but we need to find you some other occupation more suited to your looks.’ She patted my hand and passed me a coin. ‘Still beautiful,’ she reassured me, ‘but differently so now. Go and buy yourself some sweets and let me worry about the rest of it.’

The very next week I started my job as an assistant in Mr Bartholomew’s Emporium of Medical Miracles. Mr Bartholomew was an Apothecary, essentially, and my role was to help him with all of the duties his large stomach and rattling chest prevented him from doing himself. I spent a lot of my days clinging to the very top of a wood-wormed ladder, fetching glass jars down from the highest shelves while he braced his bulk beneath me, peering up and wheeling me from wall to wall, calling me a good girl or a naughty girl depending on how well I’d understood his instructions. Sometimes he’d spin me round and round on my precarious perch so that my skirts flew right out and I screamed delighted terror as I held on for dear life, and then he had to sit quietly for a while afterwards, mopping at his forehead with a handkerchief.

The contents of the jars he’d shake into simmering pans and stone bowls, boiling and grinding them into potions that he sold both under and over the counter. I was fascinated by the magic contained in the little glass vials and twists of paper he gave to his customers, but he never shared his secrets or let me help him with his preparations. ‘Up the ladder with you,’ he’d say after I’d asked too many questions, grabbing a broom and feinting a playful rush at me. ‘I need a pinch of something from the very top shelf again. Up with you, missy.’ And back up the ladder I’d go.

When I wasn’t fetching things down for Mr Bartholomew he’d have me sit in the padded window seat overlooking the throng of the street with a book on my lap. No matter that I couldn’t read it, he told me, it improved the look of the place; let passing trade know that this was a serious establishment. And almost as soon as I sat down, arranged like a shop dummy in that wide, tall window, my legs crossed just so, the bell above the door would jangle and in they would file. Always men, and always in a shifty sideways shuffle that brought them to me rather than to the counter. I never raised my eyes from the nonsense marks that leapt across whatever page I had my book open at; I was a statue they could hover around until Mr Bartholomew, beaming, stroking his fingers through his long plush beard, called them over and sold them things that came from a double-locked cupboard by his feet and warranted the special brown paper wrapping.

Things carried on for a year in that vein and I was happy enough. Mr Bartholomew met with my mother regularly, treating her to tea and cake at a hotel and talking over my progress. My progress, from what I could see, was limited. I did exactly as I was told and had so little in the way of responsibility I couldn’t imagine my absence as an assistant would be noticed a great deal. But Mr Bartholomew’s sales ledgers told a different story and he was delighted to continue with the arrangement. He even raised my pay.

I had always thought that Mr Bartholomew felt a kindly, paternal affection for me. There were times I even wondered if he were my father. So it came as quite a shock when, one afternoon, I glanced down from my ladder-top to see his head craned almost off his neck as he riveted his gaze onto the private contents beneath my skirt. I yelped my horror but he didn’t move away or look abashed; if anything my awareness seemed to release him from constraint. ‘Oh, you know just what you’re doing, you saucy little demon,’ he said and, scrambling onto the ladder, he slipped his hand right up there, where his eyes had been. Shock loosened my hold on the heavy jar I was balancing against the rung of the ladder and it plunged with mighty accuracy directly onto the crown of Mr Bartholomew’s head, knocking him senseless to the floor.

In an instant I was kneeling on the carpet beside him, rubbing his hands and begging him to sit up. I was terrified that I’d be taken away and hanged for a murderess, for it was obvious to me that my employer was dead. His tongue dangled, bitten through and bloody, onto his chin, and his eyes bulged bright red as if they’d been washed with dye. One foot trembled and kicked for a moment, and then was still.

Rising to my feet, I ran to the till and emptied it of money. Mother was going to be furious with me for killing Mr Bartholomew, but I hoped that a pocketful of gold and silver would soothe the worst of her ire. Snatching up scissors from the shelf, I trod quickly back to the dead man and snipped through a fistful of his beard, raising the glistening scruff to my face briefly to breathe in the smoky, musty smell of him and then slipping it into my cloth bag. I don’t know why I did this, whether the impulse served my need for a morbid memento of my crime or was more a sentimental keepsake in memory of the avuncular man who used to spin me round and round until I squealed. It felt like the natural thing to do, is all I know.

As I left the shop, palms pressed against the misted glass door, for the briefest of seconds my reflected self leaned in to meet the push of my body. It was a twisted and splintered thing, my reflection: features writhing across a face set stern and harsh with rage. We stared at each other, my demon and me, and then I pushed through her and out onto the street.

As I’d feared, my mother was beside herself with anger when I rushed home to tell her. ‘What kind of devil have I spawned,’ she spat, ‘to go around caving men’s heads in just because they wanted a touch of your fancy bits? And then to steal from them before the warmth has even left their body.’

I offered to take the money back but she was having none of that, fearing, as she said, that my returning to the scene of the crime would incriminate me further. ‘No, no,’ she muttered, sweeping the coins into her lap and covering them with her apron, ‘best let things lie as they are. But what to do with you now? You’ll have to leave and go far away, there’s no other choice.’

She made me stay in the trunk while she planned an escape, only letting me out after the sun had collapsed below the horizon and sprayed its own death in pink and peach across the evening sky. ‘They think it’s a simple case of thieving gone bad,’ she told me as she handed me a parcel of food and my coat. ‘I had a word with one or two people in the know and your name hasn’t been mentioned. They probably think you ran away in fright or got dragged off by the killer. Ha, little do they suspect.’ She shook her head and tutted, looking me up and down as I stood before her, trembling. ‘You’d best go,’ she said finally. ‘Here’s a bit of money to help you along. It’s not much, mind, but it’s all I can spare.’

I turned to take one last look at the house when I reached the end of the street, but the door was already shut and my mother back inside. Through the gloom it was a struggle to even make out which house I had lived in.

Walk west, she’d told me. Keep walking to where the sun goes at night and you’ll eventually get to a town much bigger than this one. You need to find Preston. Funny looking man, paints pictures of rich folk’s dogs, fancies himself a dandy. Give him this note and he’ll help you out. He’s your daddy so he’d better.

It took many days to reach the next town, even with the occasional lift on the back of a cart. I kept the hood of my coat close around my head and a scarf wrapped across my face in case I was recognised. I worried constantly about Mother, about how she was managing without me to keep the house clean and the money stacking in the pot. I almost turned back more than once. It was only the thought of her anger at my defiance that stopped me.

Preston, my daddy, was easier to find than I’d ever hoped possible. I joined the tail of a throng winding with purpose to one of the little market squares and hung around at the edges of the bustle until I was feeling brave enough to join them. The smell of manure comforted me and I followed my nose until I found a straw-filled pen where I bought myself a cup of milk fresh and warm from the cow, sipping at the creamy-sour meal slowly while I wandered the stalls.

People gave me a wide berth, possibly fearing that I was leprous, until I unwound my scarf and shook back my hood, unbuttoning my coat to let the spring day glance over my body. After that I was uncomfortably aware of the stares and the stumbles. I couldn’t turn around for tripping over some man or other following at my heels. I was terribly scared that my demonic self had risen to the surface again, needling through the gristle and pulp of my girlish insides to tattoo herself over my skin.

After a while, sat on a low wall at the very edge of the square, hemmed in by men with sweating bodies and twitching eyes, I buried my face in my hands and called for my father, ‘Preston,’ I wailed, ‘Painter Preston.’

A handsome man with a velvety streak of auburn whiskers framing his mouth nudged his companion and winked. He stepped forward. ‘If you call out for Preston then for the love of god let me be him,’ he said.

I didn’t hesitate. I threw myself on his chest. ‘You’re my daddy, you’re the artist Preston?’

He held me in his arms and juggled me from palm to palm, smiling down at me. ‘Sure I’m your daddy, my darling,’ he said. ‘I’ll be whatever you want me to be.’

It was really that easy, finding him. I picked up my bag and let him lead me from the square.

For an artist, my father seemed strangely un-artistic. There were no paintbrushes or easels in the room he rented. No dogs ran around, waiting for their likeness to be committed to paper. When I asked him about this he muttered obscurely about how times had been hard and he’d had to change career, along with his name. He was now Jake and he was a gambler, a professional card player. I was to be his assistant.

There was even less to do than when I’d worked as an assistant for Mr Bartholomew. I merely accompanied my father to the many bars and clubs he frequented and stood quietly behind him through long nights, one hand on my hip and the other on his shoulder. When he took his handkerchief out and coughed into it that was my cue to walk around the table slowly, circling the men, pausing randomly and continuing on until I was back at his shoulder. I didn’t like the way the players’ eyes were tugged around by the movements of my body as if I held the end of a piece of string kited to their eyeballs, but after I’d completed a circuit Daddy Preston, who I could never remember to call Jake, always won his game. He called me his lucky penny, his good luck charm.

I slept curled in a hammock above his bed, and kept our little one-room home sparkling clean: sweeping and scrubbing every day while he snored in the corner beneath a heap of blankets. There was a lean-to just outside the back door where we bathed in a tub, and a tiny garden, no more than an arm’s-breadth in any direction. He sent me out there to cook meat over the fire pit when he had visitors. The gathered men ate with their fingers, sitting around a folding table and wiping grease all over my father’s playing cards, while I crouched in the shadowed doorway and watched. They were so loud and rough, these visiting men, coarse both in their language and their actions. Towards the end of the evening, after the beer had been drunk and the cards thrown to the floor in despair, they sought me out and ordered me into the room. They made me swirl before them like a flamenco dancer or, worse, sit on their laps, shifting uncomfortably on top of their bony thighs. They were suddenly still and quiet at those times, holding tight to my hips and gazing dreamily into nothing as I squirmed against them. My father, flushed with drink, laughed and winked and wouldn’t look at me.

No matter how I worked to jolt his memory, Jake never appeared able to evoke his love affair with my mother. He’d nod vaguely when I described the town I grew up in, our little house, and Mother’s unique habits and mannerisms. ‘That’s her,’ he’d say. ‘I remember her well. Proper little beauty, she was. I’d have married her in a flash if she’d have had me.’ Then he’d lose interest and change the subject, tell me to pour his bath or darn the holes in his trousers. I looked for myself in him but couldn’t find a single feature that resembled my own. Grateful for his protection and anxious at the thought of its loss I never voiced my fear that he may have been bamboozled by Mother into claiming me as his when he could have been just one of many contenders to that role.

The night he wagered and lost me at cards, as casually and indifferently as if I’d been a handful of pennies or a pair of boots a size too small, the demon in me rose up and killed both him and the man who’d won me. His mood had been ugly for several days, his winning streak exposed as nothing more than a cheating trick for which he blamed me entirely. If I hadn’t been so obtuse, taken so long on my circuit around the room, the card tucked up his sleeve wouldn’t have fixed itself through sweat to the skin of his arm, stamping scarlet diamonds across his wrist for all to see when he finally eased it out and raised his arm to drink. There had been a fight, brief and savage, and then he was hurled from the bar with me clinging like a puppy to his heels. I’d supported him home and cleaned his wounds while he emptied the room of beer and cursed me.

When he collapsed onto the bed he dragged me with him, pinning me under the weight of his fury and his shame, burying his sharp wet teeth into the curve of my neck, nipping at me, nipping, and then he fell abruptly asleep. Too weak to shift him and wriggle free, I lay for hours squashed beneath the length of his body, drawing breath in shallow gasps and dreading the moment he’d wake. But with the morning came sobriety and the sickness that always followed his more spectacular drinking sessions. He rolled off me and lay clutching his head, turned to the wall; neither of us mentioned the night before.

We had to travel further in order for him to play cards with strangers who hadn’t heard rumours of his tricks. Now that I knew I wasn’t really a lucky charm but nothing more than an accomplice to his dishonest ways I resented the evenings I spent enticing the attention of the other players away from him, though I performed the duty without protest. I even played up to the role, undoing the top buttons of my blouse and singling particular men out for a special smile. I would have done anything to win back my father’s affection and remain at his side.

Clumsy and unconfident in his skills now, his cockiness shattered by the beating he’d received, Jake glowered defensively through each game, betting recklessly with his infrequent winnings, until he had nothing left to bet with. Nothing left but me.

I was risked, and lost, for an insultingly low amount. I used to earn more than that in a month when I worked for Mr Bartholomew. My new owner, tripping over his own feet in his urgency to get his hands on me, was a man I feared as much as loathed; his narrow eyes, oozing an infected yellow sludge that crusted across the peak of his cheekbones, gored me like arrow tips; his hands clenched into fists as he wetted his fat lips and imagined lord knows what depravity.

Standing as tall as I could manage to meet this man’s assault, I made a last plea to my father which he waved aside as if I’d made a petulant request for a bag of sweets when dinner was already on the table. ‘What’s done is done, L,’ he said, shrugging. ‘You made your bed when you decided to take up with me.’

I spun to face the wall, to hide my despair from the leering men. My reflection flashed past in the smoky mirror set above the gaming tables and I saw lurking there the demon who had shared my body since birth: my bitter demon-self who didn’t tolerate such abuse. I swung my head to chase her presence, to acknowledge her, and when I nodded she nodded back and slipped free of the loosened leash around my spine.

We moved together, her cold fury controlling my timidity, my pathetic desire to submit and thus meet approval and love. We snatched from the bar a glass for each hand, and we smashed them to jagged teeth. One for each throat. Blood gushed as if the men had been Champagne bottles, their bodies uncorked. I knelt beneath the warm red fountain that bonded me to him and stroked my father’s dead cheek, lifting a tuft of severed beard from his chest and wiping it clean of gore before secreting it in my pocket.

We didn’t need to kill anyone else: the other players fell back from their seats and held up their hands or scuttled away, the bar tender continued to wipe clean his shelves. But my demon wanted more. She fought me in a frenzy of warrior-lust, desperate to over-rule my human self and destroy every man in her path. It took all my strength to subdue her and wrestle us both through the door, out into the street and then onto Jake’s house, where I gathered what I could before fleeing the town.

From that night she paced the confines of my body restlessly, liberated by my acceptance into claiming the spaces of my innards as her own. She pressed along the knots of my skeleton and curled her hands inside mine so that my nails stabbed crescent moons into my palms. She glared out at the world through my eyes and pushed against my smile with her severe mouth, twisting my placid appearance into a grotesque grimace. Guardian of my virgin body and keeper of my soul, she spat at any man who tried to touch me without my consent, and woke me from my nightmares with a gentle rocking, her arms within mine wrapped around my ribs.

I wandered with aimless sorrow, unanchored from my own past and reluctant to fully embrace my demon, lonely as I was for the comforts of human companionship that she disdained. In town after town I tried to make a home for myself, and town after town we fled together after one liberty too many had been taken by the men-folk. We left them maimed and murdered in our wake, their dead ears filled with the alarm call of church bells sounding our exit. I trusted too much and my demon trusted not a jot, trusting me and my easy-won heart least of all. With every killing she gained in strength and I lost more of myself, until I feared that I would become entirely re-cast in a form as pitiless as she.

My need to settle somewhere, to be safe and warm at night, wore us both out in time. Eventually she retreated to the very back of my skull and allowed me to forge a cautious life for myself in a small town fringing the sea, while she monitored my interactions suspiciously and reared up in an instant if she scented danger in the citrus tang of a man’s handkerchief or a lingering gaze. I worked as a living shop dummy, modelling clothes for rich ladies to purchase, and I lived quietly. I believed myself anonymous, my looks warped enough by my demonic self to have been scoured clean of beauty, and any urges I had to join the ranks of my fellow courting females I stifled before the desire was even fully formed. I thought myself content with my lot, until the day my beloved Benjamin, office clerk and saver of injured birds, stumbled over me as I crouched in a park and tried to free a starling from its noose of twine.

He was kneeling beside me, his hands covering mine, before I had a chance to move away. ‘Let me see,’ he said, and my demon reared up and let out a low growl through my tight-pressed lips. ‘Poor little thing,’ he murmured as he used a pocketknife to cut the bird loose then tipped it upside down and watched its legs kick the air before he declared it unharmed and set it down on the ground. We watched together as the starling stretched each wing in turn and dug its beak through the plume of its breast, then leapt into the afternoon and flew off.

He turned to me then and smiled, reaching out a hand to help me to my feet. I tumbled straight into love with him, immediately and gleefully, and gave him the eager clasp of my fingers along with my address when he asked to collect me later in the evening to escort me to dinner.

Our courtship cart-wheeled me into morning song and night-time yearning. I couldn’t sit still for juicy thoughts of my Benjamin’s sweet lips and earnest conversation. My joy stunned my demon as effectively as an exorcism, reducing her to a bruise that haunted the nerve-endings at the very base of my spine, a tender spot that throbbed occasionally to remind me that she was still there. But even she was tempted to believe in this love-affair’s happy ending, her anger soothed at last by the kindness and the courtesy my suitor showed to me.

I would have gladly shared the secrets of my body with him if he’d only asked. I waited for him to say something, to make a move that would enable me to respond with passion, but even at his most ardent he never did more than kiss the palm of my hand, tongue flickering so lightly against my skin I would have thought I’d imagined the intimacy if it weren’t for the wet smear it left behind. Too shy to proposition him, both my human and my demon self too baffled to know how to respond, I held myself in stasis for what felt like years and years but was in truth mere months.

When I came upon him in my room one sunny evening, wrist-deep in the drawer that contained my undergarments and the few treasures I owned, dismay a scarlet riot across his face, my demon unfurled herself and plunged the length of my body, filling me from head to toe, shrieking her rage even as I stood blinkingly uncomprehending in the doorway. Her fury was the sharper for being so surprised; I think she suffered the loss of faith in him as much as I did. Dazed by love as I had been for so long, I didn’t have the strength to subdue the worst of her and could only let myself be dragged across the room. We picked up my nail scissors and buried them deep into my Benjamin’s right eye. His left stared at me in horror and terror.

As he fell to the floor his hand opened and I saw my finest pair of stockings, the pair I always wore when he took me to dinner, were threaded through a band of gold. A question he was waiting to ask, and an answer I could never give. He stuttered nonsense words as I held him against me and sobbed. When I lowered my face to his, our lips close enough to mingle breath, he managed to speak briefly. ‘You killed me, you demon,’ he whispered. ‘You demon, L.’

We left him there, bleeding but still alive. I like to believe he lives still, and is married and happy now: the gold ring he meant for me on another more deserving woman’s finger. For once it was I who had to take the initiative and effect our retreat; my demon reeled and swooned inside me. Remorse had removed the steely pins that held her together and rendered her soft and formless. She clung to my ribs and shuddered against my heart’s beat, making swift movement an onerous task.

My happiness was over. I stood on the bridge that bordered the town I had made my home, looking back one final time before shouldering my cloth bag and walking away. My grief was cold, edged with hardness. Never again would I show my true face to the world, only to be abused by men or to abuse in my turn. I headed for the distant sparkle of a travelling circus some few miles off, following the lions’ roar and the smoking campfires. I stopped before I reached the crowds and sat with my demon a while in the dark. Together we held the lustrous beard I had woven from the face hair of the men we had killed, stroking the fine threads. I fastened it to my face with glue I had purchased for just such an eventuality. Now I was neither man nor woman, my demon defeated and my lonely future set in stone.

I would change my name and travel with the circus. None but the most pure-hearted man would ever see beyond my looks to love the person I was. If indeed he existed I would accept his love, but for now, for my life, I was safe from the world and the world was safe from the demon L.

MISS LUNA

I got the job because of the cheeky sparkle in my eye and the way I could project my voice so even the people at the very back of a queue could hear my words, clear and immediate as a sheet of paper torn in half right beside their ear. The sparkle I achieved by wiping a clove of garlic across my eyelids, just enough to make my peepers smart and gleam; the vocal projection came from being the youngest of ten children in a family where crying and whining didn’t get you fed.

Despite these attributes I was almost overlooked, so I was told afterwards, because of my slight frame and complete lack of facial hair. I could have been mistaken for a boy ten years younger than my twenty-five years. Rolled into my blanket by the campfire that first night, still dressed in the cape and stiff boots that had made a circus barker of me, still glowing from the Ring Master’s praise for the crowds I’d drawn to the Freak Show tent at a penny a person, I tried to chuckle when the muscled, whiskered trapeze twins jeered at my creamy jaw. They rasped matches across their thickened cheeks and lit cigarettes, grinning above the flaming sticks before flicking them casually away.

You should go and see Miss Luna, one of them said, jerking his head towards a tiny wagon resting beside the tiger cage. See if she’ll gift you some of her trimmings. She’s got more than enough to share.

The laughter rolled over and past me, gathering speed until it reached the boundaries of the field and forced its way through the hedges. The sound slammed caravan windows closed and flattened the ears of the dusty lions who paced and spat every waking moment of their sorry lives. But I hadn’t been raised the youngest, weakest child of ten without learning the value of shrugging off insults as if they didn’t sting. I matched their laughter with my own, hurling it higher and further than theirs could ever travel. The campfire keeled over and the Ring Master, sealed behind plush walls half a mile away, groaned and jerked in his sleep.

In the sudden smoky darkness we all settled into silence and the moon slipped her blanket of cloud and raced us to dawn.

Miss Luna was bathing in the river with the elephants the first time I saw her. Her beard, more black than brown, spilled from her lips in a torrent and ended at her navel in a delicate froth. Almost a ringlet, that pointed tip that twisted around her belly button; almost girlish. I wanted to plunge my fists into it and wind it around my palms, feel it slide over and between my fingers as I parted it to reach the hidden breasts.

She turned and saw me, took in my open mouth and riveted stare. I couldn’t read her expression behind the veil of hair, but she flinched a shoulder up to her chin and waded away, offering only her back and buttocks to my gaze. I would have called out, begged her to turn around, but then one of the elephants trumpeted mud-wallowing ecstasy and grasped her around the waist with its trunk, swinging her high into the air and onto its back. I stood and clapped as she tumbled for balance on that broad, rough platform and chided the creature lovingly, peeking at me as she finally settled herself, cross-legged.

The breeze at tree-top height fanned the beard away from her body and her nipples rose like cherry flags from the pale cage of her ribs. I fell to my knees on the muddy bank, hands pressed to my heart to keep it in my chest.

I went to her wagon late that night, after the circus had finished its last show and my duties were complete. The trapeze brothers, hunched with the lion tamer around the campfire, called and whistled after me. Ask her for a pair of heels while you’re there. Raise you up a little, stripling. I ignored them and tapped on her rotted door gently, easing cowslips from the pocket of my trousers while I waited.

Her eyes, when she opened the door just enough to look out, were slits of suspicion and fear. She saw the cowslips before she saw me, thrust as they were with such eagerness into her face. She spluttered and spat petals but took the bruised bouquet, sliding a thin arm across the threshold separating us. Thank you, she whispered. I had no breath to answer her, my knees rattled in their sockets. We both stood and waited a moment, me half-leaning against the wagon to stay upright. I tried to see past her into the scented dark of her home, wishing myself inside, and then she said thank you again and turned away. The door creaked back into its frame and I heard her sigh.

I walked back to the campfire to gather up my blanket and tin mug and then returned to her wagon. I spread my blanket on the ground beneath her window and lowered myself so that I lay fully stretched on my back, arms across my chest. On guard and close enough to hear each minute scatter of dust loosen from the floorboards and drift down onto the earth beside me as she trod the narrow safety of her home. The phases of her insomnia rode through my dreams with rocking horse rhythm, so that I woke whenever she paused, and only slept again when her feet resumed pressing miles into the worn wood.

That’s how our courtship began: the traditional way, with flowers and sleeplessness and unspeaking acts of tenderness.

My mornings peaked to joy when she stroked back the curtain at her window and leaned out to take my mug, returning it to me brimming and bitter with coffee. I’d sit with my back against the wheel of her wagon, blinking into the sharp dawn light, sip-wincing as I listened to her brush through her hair and beard and splash water at her bowl. Sometimes she hummed to herself or murmured to the threadbare tigers who guarded the far side of her wagon almost as well as I guarded the entrance. Other times, when the nights had been vast and she’d paced blisters onto her heels, she muttered words I could never quite decipher but nevertheless understood as sounds of sadness.

After she’d dressed she opened her door and joined me outside, and the sight of her drove a hook into my throat so that my pulse leapt and flailed and my voice was more gasp than greeting. I think she found my speechless boggling more amusing than anything else, but I couldn’t be certain because her lips were hidden and she rarely spoke to me. Side by side on the grass, our legs and arms close enough to set my skin on fire, she watched the circus come to life around us while I watched her. In the sunshine her beard would suddenly spark and ripple like light glinting off black ice on a lake’s surface; threads of ruddy hair writhing through that depthless dark. I longed to plunge my hands into it and draw it over my face, into my mouth. Wear it like a mask as I kissed her.

Every bustling moment that drew us into the day drew her a little more away from me, so that by the time breakfast sizzled in the pan over the fire and the Ring Master’s shadow appeared at the edge of the field she was pure ‘Miss Luna The Bearded Lady!’. After she’d eaten she shrugged herself into her role as effortlessly as she shrugged off her dress, striding in her flimsy slip towards the tent that would be her world for as long as there were paying crowds. Wolf-whistles mocked her across the field but if she understood the insult she didn’t react by as much as a stumble or a scowl. It was I who spun and dared the whistler to pucker up once more so I could plant my fist into the insolent sound and smear it across their face.

Despite the greater reveal with her semi-nakedness, that delicate slide of bone beneath skin and the shadow between her thighs, this woman was much less knowable than the Luna who lay or fidgeted above me every night. I hated to watch her become strange as she walked away. I hated calling the crowds to gather round, hated tempting them to peep through the tent flaps for a single titillating glimpse before they reeled away in delighted revulsion to call their friends over.

When they’d handed me their penny they were allowed in past the entrance, into the gloomy lair of The Bearded Lady, to spend as long as they liked watching her recline on a chaise longue and comb through her beard with her fingers, plaiting its length and teasing glass beads through the silken ropes. She shifted position regularly, playing the punters with sly awareness; crossing her legs slowly and then taking her beard in her fist and tugging it, hard and fast, so that their desire collided with their disgust and they left the tent abruptly, uncomfortable and hot.

After the bell had been sounded for the show in the Big Top the thrust and chatter of the crowds ebbed away into the gloaming, chasing the glitter and roar of the main spectacle like dizzy moths. This was my evening’s peak towards joy: my patrol around the side-show tents; ushering stragglers, tying flaps closed, collecting paper twists of chestnuts from the ground to save for our supper. Circling Luna in ever tighter loops until she finally stood framed against the canvas triangle of her working day and I rushed to her side, coat outstretched to drape around her shoulders and joy an explosion inside my head so that my eyeballs bulged with the force of it.

We spent those evening hours as we spent our dawn ones; side by side outside her wagon, watching the sky dance and flicker with the circus lights, waiting for the show to finish. She listened quietly as I told her about my childhood, my mother’s unfortunate penchant for men who either died or left her before their gift in her belly had even swollen to full ripeness. I told her about the pigeon I’d reared and carried everywhere on my shoulder until the day my older brother turned its flesh into a pie and its feathers into a head-dress that he couldn’t sell so ended up swapping for two maggot-tunnelled apples.

And I told her that I loved her, had loved her since the first moment I saw her, and that I would happily sleep on the ground beside her wagon every night until I died, just to be close.

Luna, I whispered on the last night before the circus packed up and moved onto the next town. The atmosphere of bustle and urgency all around us, the shouting and shuttering, had emboldened me. Luna, will you let me kiss you?

She turned to look at me and I saw the smile buried beneath the charcoal smudge of beard. She leaned a little closer and cupped a palm beneath my soft chin, tipping it up so that she could stare into my eyes. We stayed like that for a while, unmoving while the circus folk flowed around us and the moon scratched shadows through the trees that bordered our corner of the field. Then she took me by the hand and led me inside her wagon.

I let her guide me to the bed; I could barely place one foot in front of the other and was glad of the help. I lay back and watched as she slid out of her clothes and stood before me, naked as the first time I saw her. I wanted to perform some grand and extravagant gesture, fly right up into the night sky and tuck a star under each arm, just for her, but my body was shaking so much I feared it would be a challenge to accomplish even that most natural of manly actions her nakedness implied was forthcoming.

Luna knelt before me and parted my legs, resting her arms on my thighs. Her beard trickled down between us, the tip bouncing slightly with the animated roll of her lips. Before I met you, she told me, I didn’t believe it was possible to feel happiness again.

She raised her fingers to her cheekbones and began to rub at the skin there, massaging with strong downward strokes.

I lived a damaged life. I needed to disappear and never be found, so I joined the circus.

She winced, whether at the memory or at the scouring she was giving her face, I didn’t know. I wanted to take her hands and hold them to my chest, tell her to be still. In sudden panic I wanted to tell her to stop scratching like that and stop talking, please stop talking. I plunged forward and kissed her. Her writhing fingers jabbed me in the nostril and I shrieked.

Hold out your hands, she said softly. I tried to cover my eyes but it was too late. I had already seen.

There. She laid her beard into my lap and smiled up at me. I saw how beautiful were the angles of her face, the red lips and fragile fold of her jaw. Her cheeks pink and smooth as cherry blossom petals, the tiny patches of glue resting on her skin like dew drops. Across my trembling legs her beard arched and twitched like a dying, broken-backed animal.

I jumped to my feet and grabbed at the grotesque fakery, tumbling Luna across the floor and not caring if I hurt her. I tried to throw the beard across her dark wagon, but it stuck to my hand as if it belonged there. In desperation I thrashed and danced and tore it clean in half, flinging the twin pieces as far from me as possible, scattering a cloud of hairs that glided and drifted around us.

As I lurched to the door and put my shoulder against it once, twice, three times before it burst open and spilled me out onto the grass, Miss Luna cried out behind me. I didn’t stop, I couldn’t stop, to speak to her, but scrambled to my feet and ran, past the trapeze twins and the lion cage and the collapsed tents. I covered my mouth with my hands to suppress my sobs and felt the prickle of hair attach to my chin, the sticky transference of threads from her face to mine. Her beard a gift to me.

LITTLE MATRONS

We used to stand, as one and as many, in the window in the front bedroom. Layered safely inside each other until little hands cracked us like eggs and spilled each fractured secret to reach our unbroken heart. Our pip. Then, lined up side by side on the sill, looking out over the green slide of garden to the lane beyond the spike of hedgerow, we had the best view in the house and years to enjoy it. Dust settled on our wooden smiles. Bright sunshine faded our bonnets and winter damp cracked our complexions, but nothing dulled the painted roses in our cheeks.

Little hands grew larger and then disappeared. We didn’t miss their occasional rough play, the way they’d twist us at our emptied waists and then forget us, leave us stranded for months at a time with our feet marching in opposite directions to our stare. We were glad when they finally left and forgot us for good. We had the world to watch, and we were together.

The room filled again with more little hands, pushing and shoving in the spaces behind the glossy brush strokes of our hair. We were used in violent battle scenes, forced shoulder to shoulder with tin soldiers; we were brutally halved and abandoned; tipped upside down, skirt over head, and filled with cigarette ash and peanut shells. We’d never been so abused as during those years. By the time they left and the house was empty once more we were scarred and aged, dirtied and distressed, but still together.

A dog’s wag was the thing that eventually began the breaking-up of us. A tail hard and curved as a hockey stick swept our shrieking second-smallest from the sill to the floor and rolled her under the bed. Chipped face pressed into the dark wood boards, blinded and mummified by the fluff of decades, she’s there still. We tried at first to keep her spirits up by describing each season’s changing view, the ash tree’s summer growth spurt and the molehills studding the lawn, but after a time she stopped asking questions. Now she doesn’t even cry, though I know she hears me call to her.