Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: The Isles of Scilly Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

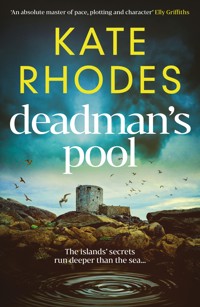

When Ben Kitto discovers the body of a young woman, buried near the ruins of an old isolation hospital on the island of St Helen's, he is convinced the killer is hiding in plain sight … and determined to take more lives. The breathtaking, gripping new instalment in the Isles of Scilly Mysteries series… 'A classy, edge-of-the-seat thriller which will keep you guessing throughout!' B.A. PARIS 'An absolute master of pace, plotting and character' ELLY GRIFFITHS 'Rhodes does a superb job of balancing a portrayal of a tiny community oppressed by secrets with an uplifting evocation of setting' Sunday Express 'No one produces more elegantly written work than Rhodes … and this eighth instalment in her Isles of Scilly Mysteries series has the same acute sense of place as any of its predecessors, with Kitto as richly characterised a protagonist as ever' Financial Times ––– DI BEN KITTO RETURNS… A SACRED ISLAND Winter storms lash the Isles of Scilly, when DI Ben Kitto ferries the islands' priest to St Helen's. Father Michael intends to live as a pilgrim in the ruins of an ancient church on the uninhabited island, but an ugly secret is buried among the rocks. Digging frantically in the sand, Ben's dog, Shadow, unearths the emaciated remains of a young woman. A SHOCKING MURDER The discovery chills Ben to the core. The victim is Vietnamese, with no clear link to the community – and her killer has made sure that no one will find her easily. A KILLER ON THE LOOSE The storm intensifies as the investigation gathers pace. Soon Scilly is cut off by bad weather, with no help available from the mainland. Ben is certain the killer is hiding in plain sight. He knows they are waiting to kill again – and at unimaginable cost. ____ 'Dark, intense, and expertly crafted' RACHEL ABBOTT 'An atmospheric and moving depiction of a tightly knit community in a rugged and often dangerous landscape, Deadman's Pool is tense and deftly plotted, the pathos fuelling true suspense' Guardian 'It's always a bonus when a story gives a psychological insight into a place as well as the minds of the characters. In this case it's the slightly claustrophobic intensity of the Isles of Scilly that is expertly revealed through the eyes of DI Ben Kitto in the latest of this superb series' Daily Mail 'Written with all Kate Rhodes' trademark atmosphere and intrigue, this thriller keeps the reader guessing right to the end in a truly absorbing, chilling story' People's Friend 'Poet and novelist Rhodes has always been an elegant writer and that remains the case with this new novel. It's moody and suspenseful and poignant but ultimately hopeful. Like Ann Cleeves, with Shetland and her Jimmy Perez character' Crime Fiction Lover Praise for Kate Rhodes 'Kate Rhodes directs her cast of suspects with consummate skill, keeping us guessing right to the heartbreaking end' LOUISE CANDLISH 'A vividly realised protagonist whose complex and harrowing history rivals the central crime storyline' SOPHIE HANNAH 'Expertly weaves a sense of place and character into a tense and intriguing story' METRO 'Rhodes does a superb job of balancing a portrayal of a tiny community oppressed by secrets with an uplifting evocation of setting' Sunday Express

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

THANK YOU FOR DOWNLOADING

THIS ORENDA BOOKS EBOOK!

Join our mailing list now, to get exclusive deals, special offers, subscriber-only content, recommended reads, updates on new releases, giveaways, and so much more!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Thanks for reading!

TEAM ORENDAii

iii

deadman’s pool

KATE RHODES

iv

v

In memory of Thomas Ford – ‘Fordie’ – a special young man, remembered with love by his family, friends, and colleagues in the lifeboat crewvi

vii

‘Our dead are never dead to us, until we have forgotten them.’

—George Elliotviii

Contents

PART 1

1

Monday, 8th January

Lao is gone. Mai has been without him for two days, and his absence makes her whole body ache.

The freezing basement where she’s trapped has been her world for so long, every object is carved into her memory, like the Vietnamese relatives she’s determined not to forget. The room is four metres long and two metres wide, containing only a few pieces of shabby furniture. Her single bed frame is covered in nicks and scratches. Mould blossoms from the walls in powdery black circles, and a broken radio lies on the floor by her bed. If she climbs onto the table in the corner, it’s possible to glimpse the garden outside. She stands there often in summer, longing to see birds and flowers in bloom, beyond the confines of her prison. The window is obscured now by brambles running wild, despite the winter chill.

She used to scream for hours, praying someone would hear, but that ended years ago, when she realised it was pointless. Her cell has few comforts. There’s a toilet and sink with cracked enamel, and hooks on the wall for the second-hand clothes she hates. The man only provides dresses suitable for a child, even though she’s turned sixteen. They bring her little sister Tuyet to mind. She lived with Mai from the day of their capture – until six months ago, when the younger girl vanished in the middle of the night. Mai doesn’t know where Tuyet was taken, but still thinks of her every day.

Life is harder than before. The man used to bring them food every night, and even taught them English from a book, if they behaved well. Now the heater is broken, and she’s always cold.

Mai has only been allowed to leave her cell a handful of times. The man made her lie on the backseat of his car, covered in 4blankets, late at night. When she emerged, she was surrounded by trees. The fresh air against her skin felt like a miracle. She could hear night birds calling and smell rain on the dry earth. The wind seemed to call her name as it rushed through the trees. Suddenly the lure of freedom was overwhelming, and her need to find Tuyet. Mai ran away, racing through the dark woods, until she tripped and fell. The man caught her and dragged her back to his car. He’s punished her ever since, for abusing his trust.

When she fell pregnant in April, he was furious, even though it was his child. The beating he gave her left bruises all over her body. Mai was half-starved by the time he finally returned, yet the baby kept on growing. She lay in bed at night, smiling whenever it stirred. The baby moved restlessly, like it was desperate to escape into a bigger world.

Mai’s labour was terrifying. She delivered her child alone, in agony, but when she held him for the first time, the bond was instant. She called him Lao, in honour of her father. It was easy to ignore the man’s curses when he delivered nappies and a Moses basket. But he turned away whenever she breastfed Lao, like it disgusted him to watch.

The Moses basket is empty now, yet Lao’s scent of soap and innocence remains. Mai touches the padding, where his body has left a hollow. She can still trace it with her fingertips. Lao was less than a fortnight old when the man took him, two nights ago. What if he never returns, like Tuyet? How will she survive? When Mai closes her eyes she’s forgotten how to cry; her tear ducts are empty. Even her mind feels numb, emotions cauterised. She stares at the wall instead, remembering how it felt to cradle her son in her arms.

2

The sea is behaving itself when I reach Hugh Town harbour this morning, which is rare in mid-winter. A fresh storm is already gathering on the horizon. That black ridge of cloud will attack Scilly’s beaches soon, before spinning west to create havoc at sea. My wolfdog, Shadow, is in his element. He races down the steps from the quay, through clumps of seaweed, then over sand exposed by the ebbtide, his fur ruffled by the harsh breeze. Town Beach on St Mary’s is one of his favourite places to explore. He loves hunting for old lobster pots to chew or rancid fish to dig up, until he returns smelling foul.

‘Get back here, you filthy mongrel,’ I yell out.

Shadow pauses a hundred metres away to look back. He releases one contemptuous bark, then continues running. Soon he’s just a pale-grey streak, vanishing into the distance.

‘No respect whatsoever,’ I mutter.

The police launch is moored among the crab boats at the end of the quay. My first duty of the day will be to deliver Scilly’s only Roman Catholic priest, Father Michael Kerrigan, to St Helen’s. It’s an uninhabited island, two miles away by sea. He’s going on his annual pilgrimage. When I heard he was planning to sail his ancient boat there alone in storm season, I volunteered to ferry him across. My job as deputy chief of police in the Isles of Scilly includes many unusual duties, but the most important one is keeping the population safe, even if that means providing a taxi service occasionally.

I’d hate to spoil Michael’s view of St Helen’s as a sacred place, but the trip will help me check for signs of smuggling too. Most people think the trade died out here centuries ago, yet it’s alive and well, and winter is peak time for bringing contraband drugs, booze and cigarettes through the islands. My team has been working with the Maritime and Coastguard Agency all year to try 6and bring landings on the off-islands under control. But a few night-time patrols won’t stop packages being dropped or collected from Scilly’s quietest corners, unless we’re vigilant. The ocean is a paradise for small, unlit boats. Our lifeboat even had to rescue an inflatable dinghy with three terrified young women on board last year. They were Albanian nationals, too afraid to name the traffickers who left them drifting on the open sea. The mainland police ferried them to the nearest immigration centre. I’d like to believe they stand a better chance in the UK, but their fate is uncertain. They often wait months for their applications to be processed.

Michael’s voyage is much less risky. The prospect has put a smile on his face, like he can’t wait to get closer to his God. He won’t be getting a luxury ride on our police launch, but at least it runs well. The twenty-five-foot fibreglass hull is covered in scrapes, from bumps against the harbour wall and collisions with unlicensed boats. The dayglow letters announcing that it belongs to the Isles of Scilly Constabulary have almost worn away, but our pathetic budget means it won’t be replaced anytime soon.

The priest is approaching when I jump on deck, feeling the vessel shift under my weight. He’s small and wiry by comparison, dressed in waterproofs and trainers, his grey hair cropped short. Michael’s brisk pace proves that he’s in good shape for a man in his fifties – a result of refereeing local football matches. His passion for sport is almost as profound as his faith. He looks expectant today, like he can’t wait to leave harbour. I’m surprised to see he’s only carrying a small rucksack for his trip to St Helen’s.

‘No other luggage, Michael?’

He steps onboard. ‘I’m only going for two days. Thanks for the lift, by the way. My boat’s knackered. I need Ray to fix the engine, again.’

‘What about food, and a sleeping bag?’

‘It’s a pilgrimage, Ben, not a spa break. It’s meant to be challenging.’ He sounds amused. ‘St Elidius lived there without 7any creature comforts for decades. It won’t hurt me to rough it for a while.’

The man’s grit is impressive. I like camping too, but not in freezing weather, without food or access to a hot shower. There’s nothing on St Helen’s apart from ancient ruins, kittiwakes and wild seagrass.

I’m about to call for Shadow when he leaps onboard, panting for breath, just as I release the mooring rope. I gave up trying to second-guess how he reads my mind long ago. He rarely follows orders, but his loyalty is rock solid, so I can’t complain. Shadow forms his own opinions about the islanders. He’s grown fond of Michael, after a bumpy start, and settles by his side as we leave the quay.

I’ve always loved boats, so it’s no hardship to steer north, leaving the harbour’s protection behind, with brine misting my skin. If we travel fast, I’ll get back well before the storm hits. The islands lie scattered across the sea, their black outlines afloat on the gunmetal tide. Sailing is a fact of life in Scilly, where everyone learns to navigate as a child. It’s a different matter for strangers on these waters. I’ve seen too many summer visitors being rescued by the lifeboat after damaging the hulls of their yachts. Every season they fall prey to the hidden mountaintops lying just beneath the surface, but I don’t need GPS to steer safely round Tresco’s eastern coast, provided I keep my distance.

Father Michael looks pleased when St Helen’s appears on the horizon. There’s little point in talking over the engine’s drone, as the boat scuds over low waves. I try to imagine myself in his shoes. He’ll spend forty-eight hours alone on a wind-ravaged island that was last inhabited three centuries ago. The idea carries little appeal. My son Noah is one year old, with my wife Nina and I juggling childcare between us. I never enjoy leaving them behind, despite being bug-eyed from sleep deprivation most days.

We’re drawing level with Tresco’s Pentle Bay, where the arc of white sand looks inviting, even in winter. The North Islands lie 8directly ahead, the wind dropping suddenly when St Martin’s hilly profile looms over us.

Michael turns to me as we approach our destination. ‘Have you visited St Helen’s much, Ben?’

‘Just a few times in my teens, but not since. The council don’t like visitors because of the birds’ nests, do they?’

‘It’s okay if you avoid the cliffs. That whole area’s protected.’

‘Someone told me it’s full of burial sites.’

He nods. ‘You can’t dig there, in case you disturb a monk’s unmarked grave. Do you know the island’s history?’

‘Only that it had a hospital and a church, back in the day.’

‘Take a look while you’re here, the place is extraordinary.’

‘Why, exactly?’

‘I can’t define it. You’ll feel the atmosphere for yourself.’

‘You won’t convert me, Michael. I’m a diehard sceptic.’

‘So was I, until this happened.’ He taps his dog collar, grinning. ‘Keep an open mind, my friend. God might be waiting for you.’

‘I’m past saving.’

‘No one’s a hopeless cause, believe me.’

The priest goes on teasing me as we cross the calm waters of St Helen’s Pool, with the island filling the horizon. It’s always tranquil here, unless there’s a force-nine gale, the waters protected from east and west by the stony ridges of Tean and Northwethel. I can’t explain why I feel edgy as we moor on the quay. Maybe it’s the air pressure changing with the coming storm, but my heart rate quickens.

The island looks innocent enough, with its southern coast edged by white sand that glitters with mica, and granite boulders strewn along the shore. It’s shrunk over the years, thanks to rising sea levels. High tides have rearranged the coastline, drowning more of its beaches every winter. Cairns stand tall on the rise, like a family of giants. No one knows who created those landmarks from thousands of hand-sized rocks, but they appear to be on guard duty, prepared to defend St Helen’s from invaders. 9

When I glance back at the sea, I spot a motor cruiser departing at top speed. It must have been visiting St Helen’s, because there’s nothing between the island and the USA’s eastern coast. It’s too small to identify, so I take a photo with my phone, planning to enlarge it back at the station, in case it’s a smuggler.

Michael seems happy now we’ve arrived. His smile is peaceful when he turns to me, but I’m still unsettled.

‘Otherworldly, isn’t it, Ben?’

‘It’s lucky I don’t believe in ghosts.’

‘Christians call these places “thin”. The gap between us and the spiritual world is narrower here than any shrine I know, even Lourdes. It was hallowed ground for centuries.’

‘It still feels haunted.’ The sky overhead is boiling with clouds. ‘I’d better get back, before the rain hits.’

‘Do a quick tour with me first, please. It’s part of your heritage.’

He strides inland before I can reply, appointing himself as my guide. It’s lucky that St Helen’s is less than half a mile long. We take just five minutes to march over hard sand to the ruins of the eighteenth-century plague hospital, known as the Pest House. The low granite structure is smaller than my cottage. Its chimney stone is still intact, even though the roof and windows gave way decades ago. I’ve known of its existence since I was a boy, but never stood inside its ruins.

Michael explains that sailors were forced to quarantine here, instead of infecting the islanders with diseases caught on distant voyages. Men languished in grim conditions until they either recovered from cholera, typhus or the plague, or died of their illness. It must have been terrifying, knowing the pendulum could swing either way. The building would have been packed to the rafters with dying men, more like a prison than a hospital. Many of them never made it home. The graveyard outside is full, with headstones poking up from the weeds. Shadow seems spooked by the place too, barking at top volume.

‘Show some respect,’ I hiss. 10

He continues making his infernal noise, jumping up repeatedly. I see now that my dog’s pale-blue gaze seems to be asking for something specific, so I pay more attention. He only acts this way when he’s sure something’s wrong.

‘What is it, Shadow?’

He chases across the beach, then looks back, expecting me to follow. It could just be the unfamiliar territory that’s excited him, but there’s no time for games. I should be leaving, yet Michael seems determined to complete his history lesson. We cross two hundred metres of shore to reach the site where the religious community built their church a thousand years ago.

I notice something much less spiritual, close to the ruined buildings. It’s the remains of a campfire, with food wrappers and half a dozen beer cans scattered across the sand. Michael shakes his head. Part of his reason for coming here is to keep the island pristine. Last year he filled three binbags with plastic and ruined fishing nets, washed up by the tide. He explains that St Elidius built the circular prayer oratory alone, in the eighth century, and lived there as a hermit. His bones were interred beneath the altar as relics. The religious community he founded remained here for three hundred years. I can see the foundations of the monk’s cells, still standing beside the oratory’s granite walls.

Shadow’s behaviour distracts me as I absorb the information. He’s barking at the top of his lungs now, shattering the island’s peace, then he starts digging at a frantic pace. Soon he’s created a hole so deep his body disappears into the sand. I try to ignore his antics.

‘How did the monks survive here, Michael?’

‘It tested them, but hardship was part of their calling. People say they grew crops, sold holy water, and kept bees for honey. The brothers charged passing ships taxes too, in exchange for blessings, or a pilot to give them safe passage to St Mary’s.’

We’re still talking when Shadow puts his head back and howls.

‘Something’s upset him, hasn’t it?’ Michael says. 11

‘He’s just being a drama queen.’

Rain is starting to spit when I walk over to check why my dog’s so excited. I see a fragment of black plastic at the bottom of the hole, but Shadow is still digging. His frantic movements kick sand into my face, until I pull him away, then kneel down to see what he’s found. It looks like a smuggler’s cache. They often bury contraband on our beaches, leaving markers behind so runners can find them. This one’s parcelled up neatly, with gaffer tape, like all the rest.

I was hoping to save Michael from the grubbier side of island life, but I can’t just leave it here. It might contain cannabis resin, or heroin. The smugglers probably lit a fire and drank a few beers before sailing away, leaving their toxic goods behind.

‘What kind of philistine leaves rubbish on a holy island?’ the priest mutters.

‘Let’s find out.’

I tug at the plastic, but it’s lodged deep in the sand. Shadow seems eager to discover what’s inside too, whining softly as my hands fumble in the cold, piercing the wrapping with a key. Someone has wrapped the contents in soft blue fabric, instead of the usual bubble wrap.

‘What on earth is it?’ Michael asks.

A lock of ink-black hair spills across my hand. Instinct makes my eyes blink shut, but when they open again, I see part of a human face, blanched white, like marble. Is it male or female? The jawline’s so narrow, it could even be a child. My hands shake as I cover those ruined features with fabric again. The body lying in the hole is partly decomposed, the skin breaking down.

Shock keeps me frozen in place. Why would anyone kill such a young victim, then bury them under a metre of sand? Maybe it’s collateral damage after a drug deal went wrong? Or we’re facing a new menace: people smugglers, trading in human lives, like they’re just another commodity.

Father Michael is on his knees as I pull out my phone. His 12hands are gripped tight in front of his chest, and he’s murmuring a stream of Latin words. He appears to be calling for divine intervention, but it won’t help. I bet the victim cried out to their God too, and the howling wind was the last sound they heard.

3

The storm chooses the worst time to attack us. Rain pelts my skin, as if someone is flinging chips of ice at my face. I should get Michael under shelter, yet it feels wrong to leave the grave unguarded. I’m struggling to believe that someone sailed here for a winter barbecue, drank some beer, then buried a corpse, ten metres away. But we can’t just stand here, getting drenched. Shadow stays close, and he’s smart enough not to disturb the crime scene. He behaves the same with my son, standing guard for hours, alert to any potential threat, while Noah learns to crawl. I lean down to feed Shadow some treats; he’s performed better than many search-and-rescue dogs, his sense of smell incredibly acute. My biggest concern is the priest, whose glassy stare has drifted out of focus as shock takes hold.

Michael doesn’t reply when I ask if he’s okay. He must have seen death many times, when he delivers last rites, but nothing prepares you for a life snuffed out, then discarded so casually. There’s something contradictory about the burial. The killer cared enough about the victim to wrap their body in a shroud then use plastic sheeting to protect it from the elements. The shifting sand may have left it nearer the surface than when the grave was originally dug. But why would anyone sail to a remote island in mid-winter, when they could have cast the body into the sea? It reminds me of the Albanian women, left to drift last summer, at the mercy of the tides. Traffickers don’t just cross the Channel by the shortest route anymore – the trade is getting more sophisticated. Large boats reach obscure parts of the British coastline, sometimes offloading dinghies full of terrified victims if the coastguard get too close, to avoid getting caught.

I need evidence bags and sterile material to keep the site free of contaminants, but I’ll have to improvise until help arrives. There’s a danger of corrupting the scene, so all I can do is take 14photos, then cover the victim’s face once more, weighing the plastic down with stones to prevent further damage.

‘Where can we shelter, Michael?’

His eyes are still glazed. ‘Only the Pest House.’

‘Let’s go, before the storm gets worse.’

The plague hospital won’t provide much cover, without a roof, but it’s our best chance of escaping the biting wind. It also removes Michael from the scene, before his shock deepens. We run together, back to the Pest House, where the building’s empty windows gaze out to sea. Round Island lies just five hundred metres away. Its shape looks oddly celebratory; it resembles a child’s birthday cake, with a lighthouse flickering at the centre like a candle, flaring every ten seconds, night and day. The sight warms me, even though rain is coursing down the back of my neck. It’s a reminder that the storm may be vicious, but most of humanity is well intentioned. There are safeguards in place to protect mariners from the sea’s worst moods.

The priest’s face is pale when we crouch behind the building’s ancient stone walls. I search my pockets for food, but all I have are treats for Shadow and a single energy bar. Nina buys boxloads of the things, to counteract my tendency to skip meals then come home bad-tempered.

‘Eat this, for the shock, Michael. Don’t go fainting on me.’

He remains motionless until I give him a gentle nudge, then obeys my instruction, like a child following a teacher’s order. I peer out to sea. No help will arrive until conditions improve. St Helen’s Pool looks calm enough, but breakers are cresting in the distance, ten feet high as the swell gathers strength. Great conditions for deep-water surfing, but not for sailing over miles of rough Atlantic. My suspicions are confirmed when my deputy, Sergeant Eddie Nickell, sends me a text. He’s arranged for the islands’ pathologist to be ferried over once the storm subsides.

I’m beginning to understand the sailors’ bleak existence when they lay in the Pest House, fighting for their lives. The outside 15world must have seemed far out of reach, even though the sick men survived on basic provisions dropped by islanders on the landing quay. Only the brave would make that journey, terrified of carrying a fatal disease back home, from air-borne infection.

When I check my phone again, the signal is weak. We’re at the outer limits of communication here, twenty-eight miles from the mainland, with the nearest mast a half-hour sail away. But I manage to contact the Coastguard Agency, asking them to check if their patrol boats have spotted any uncertified vessels landing on St Helen’s recently.

It takes me three attempts to reach DCI Madron, but I can’t leave him in the dark. He insists on being the first to hear important news. My boss must be outside when he picks up, the wind keening in the distance.

‘I’m off duty, Kitto. What is it?’

‘We’ve got a major incident, on St Helen’s. I thought you should know.’

‘Are you incapable of doing your job unsupervised?’

‘Listen to me, sir, please. It’s a body, buried in the sand.’

I hear him drag in a breath. ‘Stay there. Don’t touch anything without my permission.’

‘But I should—’

‘Follow my orders, for once in your life.’ Madron hangs up, or the connection fails, but the effect is the same. My hands are tied until he gets here. I can’t even comb the area for clues.

There’s only white noise now at the end of the line. The breeze steals my curses, as my frustration builds. Madron has watched me like a hawk for the past five years, questioning all my decisions and refusing to modernise our systems. The DCI expects updates twice a day on every case I lead. He’s obsessed by formal protocols, even in a crisis, when investigations should move like lightning.

Shadow is giving me more practical assistance than Madron ever does. He’s lying beside Michael, resting his muzzle on his 16thigh, providing warmth and a calming influence. The priest’s gaze is slowly coming back into focus while he strokes Shadow’s fur.

‘Help won’t arrive for a while, Michael,’ I say. ‘You can sail the launch straight home, once the wind drops.’

‘I’m not leaving you to deal with this alone. Sorry I lost it back there, but I couldn’t believe it. Who’d bury someone, right next to a shrine?’

‘There’s been smuggling on the off-islands lately. Maybe they came here to trade, and a deal went wrong. But it’s odd the victim’s so young.’ I could mention the Albanians we found, too terrified to betray their captors, but the priest is already shaken.

‘It doesn’t make sense.’ His voice is muted, but he seems calmer than before.

‘Stay out of the wind, for now. I’ll check if anyone’s sailed here recently.’

Shadow rises to follow me, but I motion for him to stay behind. The breeze batters my face again as I leave the shelter. I used to love gales as a kid, when storm-force winds blew so hard, it felt like they could lift me off my feet. There’s no chance of that now, at six and a half feet, built like a rugby full-back, with a battered face to match, yet the gusts still feel savage as I reach the brow of the island. The ground is covered in scrub grass, heather and bracken, even though only a thin coat of soil covers the stone. People once scrambled up here to perform sky burials, but the landscape feels tainted now. The local topography has changed completely since then. Maybe the killer believed the beaches would all be claimed by the sea one day, their crime undetected.

When I reach the eastern cliffs, there’s a sheer thirty-yard drop where the land plummets into the water. I peer down at breakers hitting the rock-strewn beach, and suddenly the air swarms with birds, screaming out warnings. Herring gulls wing high into the air, defending their nests; they flap against the breeze then hover above my head, releasing harsh cries. On a normal day I’d stop and 17admire them, despite the ugly sound. I can see kittiwakes too, on the ledges below, sheltering from the wind.

There’s no way a boat could land on this side of the island, and whoever visited hasn’t left me any evidence. All I can see is rough grass at my feet, tangled with native figwort and hogweed. I retreat from the cliff’s edge, and the gulls fall quiet. I’ve never felt more out of place. This island belongs to nature, not humanity. It’s hard to believe that people ever lived here, gathering rainwater when their well ran dry, reliant on crops raised from stony ground.

My old boss’s words return to me as I head west across the island. She ran London’s Hammersmith force with an iron fist, and her advice on murder investigations was simple: act fast, using specialists and all available officers, to get the job done. Evidence degrades in minutes, not hours. I’ve got no idea how long that body has lain under the sand, but the only resources at my disposal are an intelligent dog and a priest who can’t believe that a holy site has been defiled.

It takes me just fifteen minutes to circle the island’s shores, looking for clues. I hate the sea on days like this, for its cruel sense of humour. It plays pranks just when help is most needed. I stand still for a minute, watching waves hitting the shore with force, throwing out clouds of spume. The noise may have calmed the sick and dying patients in the Pest House, but it sounds like a cracked record today, repeating the same angry message.

It’s early afternoon when help finally arrives. I see my uncle Ray’s converted fishing boat rising and falling as it navigates choppy waves then cuts across the flat water of St Helen’s Pool. He’s the ideal ferryman for the journey. My uncle spent years in the merchant navy and knows the local sea conditions better than anyone. Ray raises his hand in greeting but remains on deck, always happiest with his own company. His passengers look much less comfortable, particularly the islands’ only pathologist, Gareth Keillor. His face is greenish-white from the rough journey. DCI Madron is on the prow with Sergeant Eddie Nickell. Eddie casts 18his gaze over me and Michael, checking we’re unhurt. He was a novice when we started working together, but now he’s married with two kids, a friend as well as a colleague, with several murder cases under his belt. He no longer looks like a raw recruit. His blond hair is cropped short, his blue eyes solemn.

Madron is first to disembark. His expression’s sour as waves lap over his polished shoes. He’s wearing a smart black raincoat and looks more like a stockbroker than a cop, his movements stiff with tension. Keillor leaps onto the wet sand next, clutching his medical bag. He’s sixty-plus, like Madron, but much more agile. The man’s given me dozens of golf lessons over the years, tolerating my hopeless swing. His persona’s different today, his sense of fun hidden from view. Eddie leaps clear of the waves last of all. It’s proof that he can still perform acrobatics at the drop of a hat, like he did at school.

The DCI marches towards me, but something’s changed. He’s normally straight-backed, like a sergeant major, but today he looks frail. He tells me to act as SIO, then mutters something about bad timing, as if the body in the sand is a personal mistake. I focus on Keillor instead. His eyes appear owlish when he peers up at me through thick tortoiseshell glasses.

‘Where is it, Ben?’

‘By the church ruins; there’s picnic rubbish right by the grave.’

He shakes his head. ‘You’d better show me, before the next shower.’

Eddie looks unsettled too. He’s great at the social side of policing, able to put anyone at ease, but much less comfortable around death or injury. I advise him to head straight for the Pest House to look after Father Michael until Keillor has completed his examination. It’s easier to witness death in a photograph instead of eye to eye. Why give him nightmares too, if it can be avoided?

‘Take photos of the barbecue site first, Eddie. The rain’s probably destroyed any DNA, but try not to contaminate anything. We’ll need gloves to pack the rubbish in evidence bags.’ 19

Eddie stands his ground. ‘Can I see the victim first, boss? It’ll help me understand.’

He approaches the crime scene slowly, his shoulders rigid. Keillor is kneeling beside the hole Shadow dug, wearing sterile gloves. I watch him pull back the plastic from the victim’s face and observe those ruined eyes for the first time. Madron looks shaken, which is a first. He’s normally so guarded it’s impossible to judge his reaction, unlike Eddie. My deputy makes an odd choking sound under his breath. It sounds like a protest, as if he’d gladly punch whoever left this stranger to suffocate. I expect him to reel away then spew his breakfast onto the sand. That’s how he’s reacted when we’ve confronted corpses in the past, but this time he doesn’t flinch. It’s another reminder that he’s ready for everything policing can chuck at him these days. His face blanches, but he remains on his feet, his gaze steady.

Keillor is too immersed to notice our reactions. He gets to work fast, always the consummate professional, his movements quick and precise. I listen while he phones Liz Gannick, Cornwall’s chief forensics officer. I can hear her barking at him from five metres away. The woman’s communication style is caustic at the best of times, but her advice is sound. The body must be exhumed and taken back to St Mary’s immediately, before its condition degrades, now it’s been exposed to fresh air. Eddie is already taking photos, then helping to scoop sand away from the body. We must be gentle, trying not to disturb the black plastic sheet encasing it. Madron keeps his distance. He stands three metres away, sheltering under his umbrella, mouth downturned.

It takes us twenty minutes to expose the grave fully. I’m even more convinced now that the victim was young because the body is tiny. I bet the killer thinks they’ve committed the perfect crime – a burial on an island where people are forbidden to dig or remove items from the beach, but the tides have revealed the secret. Winter’s relentless waves have shifted the sand further north, bringing the body closer to the surface. 20

Keillor takes his own photos for the coroner’s report, focussing on the exposed face. There’s curiosity in his eyes when he looks up at me.

‘It’s a juvenile, Ben, a female adolescent most likely, based on size. The cold’s preserved her, but you can see the soft tissue’s breaking down.’

‘Has she been here long?’

Keillor stares down at the body. ‘Three to six months, I’d say. I’ll need tissue analysis to be sure, but it’s clear she was in poor health. Her teeth are in a dreadful state. That’s odd, at her age.’

I crouch down to study the victim’s face more closely. There’s nothing inside the eye sockets except blackened hollows, but her exposed jaw catches my attention. Most of her teeth are intact, but several are blackened by decay. It’s unusual these days, when most kids obsess over their teeth, bleaching them to a perfect white.

Madron only approaches once the remains are placed in a body bag, still wrapped in cloth and plastic. My boss’s face looks pinched with cold, his grey eyes matching the overcast sky. He thanks the pathologist for his work on an unpleasant day. His formality seems out of step with such an ugly crime scene, but politeness is Madron’s default whenever he meets a professional equal. The DCI saves his scorn for the rest of us.

Eddie finishes packing away the beer cans, spent matches and foil wrappers in evidence bags. Then he stands beside me, absorbing details. His resilience is part of the reason we’re friends as well as colleagues. He never shies away from things that scare him, and I try to do the same. The only difference between us is that I’m ten years older, with a stronger stomach.

‘Why here?’ Eddie asks.

‘People smugglers had a death onboard, maybe, or some islander’s got a warped idea of heaven. St Helen’s is like a churchyard, isn’t it? The ground was consecrated for centuries.’

‘This place gives me the creeps.’ Eddie shivers as the wind picks up then nods at the sea. ‘You know what sailors used to call that stretch of water, don’t you?’ 21

‘Deadman’s Pool.’

He gives a slow nod. ‘They threw plague victims in there to avoid digging more graves in this rocky soil. Lead weights were sewn into their shrouds to carry them straight to the ocean floor.’

The fact that we’re standing beside a vast underwater cemetery unnerves me as we lift the corpse from its shallow grave, leaving the scene intact. It feels almost weightless, a child’s body, not a full-grown adult. Keillor instructs us to take care as we lift it from the sand. My gaze returns to the sea as we carry it to the boat. It’s changing every minute. The clouds have dispersed, and the water has faded to a guileless blue, in the blink of an eye, proving it can never be trusted. We’ll have to sail back to St Mary’s over a drowned graveyard, carrying the smallest murder victim I’ve ever seen.

4

Mai jumps to her feet when footsteps sound overhead. She waits in silence, her mouth dry with fear. The man treats her better when she wears a smile, but that’s not an option today. Mai listens while someone prowls around upstairs. Is it him, or a stranger? The building above remains a mystery. It seems to stand empty most days, until he pays his night-time visits, but for the first time ever, she’s eager to see him. Maybe he took Lao to a doctor to find out why he was crying so much? She’s praying that today her baby will be returned to her arms, no longer in pain.

The door finally creaks open, and a food package is shoved through the gap. It slams shut again before she can reach it.

Mai lapses into Vietnamese when she calls out, too upset to remember foreign words. Pleas babble from her mouth like a fast-flowing river, but all she can hear is the key twisting in the lock. The man is leaving already. He may not return for days.

Mai wants to release the tears welling in her eyes, but what would be the point? She opens the plastic bag instead. It contains an orange, a can of Coke and a few sandwiches wrapped in foil. The bread smells stale and unpleasant. Why bother to eat or drink if her one reason for living has been taken?

She rests on her bed, exhausted. Mai remembers her mother in Vietnam leaving their cabin at dawn to take a bus to the city to clean the homes of wealthy families, while her father toiled on building sites. Her parents were well educated but took any work available to feed Mai and her sister Kim. They never complained. Their example taught her that family matters above all. She must stay strong to nurse Lao, when the man brings him back. Mai forces down bites of the sandwich. It tastes sour and the texture’s dry, but she makes herself swallow it. She must accept every scrap of food she’s given, for Lao’s sake, if not her own.

5

Ray raises his hand in a brief salute before heading back to Bryher, taking Shadow with him, leaving me to pilot the police launch to St Mary’s. It’s a typically lowkey gesture from my uncle, who never makes a fuss about anything, even though he braved foul weather to help us out. I feel bad about neglecting him recently. He stepped into my father’s shoes after his death, when I was fourteen. The least I can do is get him a bottle of his favourite Irish whiskey as a thank-you gift. Shadow will be glad to return home with Ray. He deserves a chance to dry off in front of the fire instead of waiting hours for me at the police station.

Father Michael hurries onto the police boat, once we’ve carried the victim’s body onboard. He looks eager to escape St Helen’s now his pilgrimage has been derailed. His expression is sombre when he drops onto the bench in the wheelhouse, followed by Gareth Keillor, Eddie and DCI Madron. There’s frustration in the set of my boss’s jaw, a muscle ticking in his cheek. I’ve never seen him express a personal emotion at work, but something about the case seems to have riled him. I know that he’s a churchgoer, so part of it could be anger that a pilgrimage site has been defiled.

All five of us remain silent as we pass Tean’s ragged outline, then sail south to St Mary’s. The sky is summer-holiday blue, with no clouds overhead, as the sun drops towards the horizon. It feels like the storm was a figment of my imagination. If the temperature was a few degrees warmer I could take a dip, to rinse away memories of the victim’s skin, bluish white, like broken porcelain.

The quay is empty when we moor. It’s normally a popular hangout on St Mary’s, with a coffee shop and benches for people to sit and watch the fishing fleet unload their catch, but the cold wind is keeping them at home. The island’s only ambulance is waiting for us, to place the victim’s body inside. Keillor remains calm as he nods goodbye, then climbs into the passenger seat, 24heading for the hospital’s mortuary at the top of the hill. I know he’ll get to work immediately and examine the body in sterile conditions. He’s always quick to act, driven by curiosity as well as professionalism.

When we reach the police station on Garrison Lane, the front door stands open and the place looks welcoming. The building may be covered in ugly grey pebbledash, but Sergeant Lawrie Deane is always a calming influence. The man didn’t complain about having to cancel his day off. He’s busy preparing hot drinks. Deane isn’t blessed with good looks, his greying hair shaved close to his skull, with acne-scarred skin that remains pale all year round, yet he’s a sight for sore eyes this afternoon, hovering with his tea tray. The only officer missing from our team is Constable Isla Tremayne. Our newest recruit has been patrolling the island all day, despite the rough weather.

‘Get Isla back here, can you, Lawrie?’ Madron says. ‘We need a team briefing immediately.’

Deane grabs his phone, leaving me and Eddie to help ourselves to the cakes on offer. I can’t explain why witnessing death always leaves me hungry. Maybe it’s a primal reaction, to remain strong after seeing another life wasted. I cram half a scone into my mouth before checking the photo I took of the boat leaving St Helen’s. When I enlarge it to the maximum setting it’s a hopeless blur; all I can tell is that it’s white and medium-sized, with a fishing platform on the back. Half of the privately owned boats on Scilly look identical. I have to push my disappointment aside. The case has only just begun, and the boat may have no link to the girl’s death. There will be many more pointers leading us to the killer, provided we work hard.

Madron has refused a hot drink. Through a crack in his door I catch sight of him bowed over his polished mahogany desk. He looks weakened by today’s events, but his office has few comforts. The only personal items on display are some framed photos of his wife, and their daughter’s wedding day. There are no other clues to 25unlock the man’s chilly personality, except the neatly catalogued files on his shelves, even though most police paperwork is online these days. It demonstrates the DCI’s love of ancient policing methods, while I try to keep up to date. He’s spent most of his working life behind that desk, keeping his shoes clean, which suits me fine. I get cabin fever if I’m stuck indoors for more than an hour.

I forget about the DCI while I move around the team room, printing out photos of the crime scene. When I look up from the computer screen again, PC Isla Tremayne is parking the force’s motorbike outside the station, her movements deft as she removes her helmet then hurries indoors. She’s a twenty-six-year-old graduate, a native islander and as smart as a whip, with a no-nonsense manner and a passion for sea swimming. She joined our team three years ago and seems to enjoy every aspect of her job. I can’t judge whether her enthusiasm will survive seeing our latest victim.

Madron emerges five minutes later. The team room is packed with desks, where we all huddle in winter, while the DCI enjoys his privacy. Eddie balances his laptop on his knee, ready to take notes for the incident log, while Lawrie and Isla gaze at our boss like he’s their new guru.

‘I was hoping we’d get through winter without another major incident,’ Madron says. ‘We need this wrapped up fast. Listen carefully, all of you, to my instructions.’

Madron addresses us in a sharp tone, like he’s reprimanding a gang of naughty kids. He starts by giving an overview of the crime scene. Deane’s face reddens when he hears that the victim may be a teenager. His world revolves around his two grandsons, who live near him, here on St Mary’s. Death makes him squeamish, even though he tries to hide it. Isla’s mind is much more forensic. Her gaze remains glued to Madron’s face while she absorbs the details.

‘We need information about boats seen visiting St Helen’s in the past six months,’ the DCI says. ‘We’ve found asylum seekers on Deadman’s Pool before now, so this could be connected to 26trafficking. Contact the Coastguard Agency today. I want photos from their night patrols.’

‘I’ve already requested them, sir,’ I say.

He ignores my comment. ‘A passing cruiser could have buried the victim in the sand then sailed away, unseen, but there’s an outside chance the coastguard can help. We know human trafficking is getting worse in the UK, but the last case here was a year ago.’

‘Surely they’d have thrown her into the sea and sailed away? It could be a local who knows the islands inside out,’ I say.

‘Think before you speak, Kitto, for God’s sake. No one’s been reported missing, have they?’ He stares back at me unblinking, but I won’t back down.

‘Everyone in Scilly knows St Helen’s was once a holy island. Few visitors go there, except the odd pilgrim, or birdwatcher. It’s pure fluke that we found the grave, thanks to Shadow. Whoever left that body believed it would never be found.’

‘Or maybe the killer was a visitor who’s done some research.’ Eddie catches my eye. ‘Thousands of families come here each summer. The crime may have been committed then.’

‘Why bury the body in sand?’ Isla asks. ‘It was asking for trouble.’

‘Stick to the facts, all of you.’ The DCI raps the table with his knuckles, silencing us. ‘St Helen’s is pure granite, with just a thin layer of topsoil. The ground there’s too hard to dig. The only exception is the area by the pest house, which is full of ancient graves. Our man was in a hurry, and we need to know why.’ He scans each of our faces in turn. ‘Kitto will deal with operational details. Find out all you can from the community about passing boats. Our victim may have been involved in smuggling activity.’

I keep quiet, but his point doesn’t convince me, and the look on Eddie’s face shows he feels the same. Why would a teenager die in a fight between smugglers, unless they’re dealing with human cargo, which normally happens on the mainland? But the 27DCI seems in no mood for professional argument. He’s already moving on to logistics.

‘Find a venue for our public meeting tomorrow morning in Hugh Town, please, Isla, before this gets leaked. The church hall’s closed, so find an alternative, then announce it on local radio. Inform the Island Council too, so they can spread the word. I want the incident log and timeline completed today. The body was found at ten-fifteen this morning.’

‘Shouldn’t we be guarding the crime scene, sir?’ Deane asks.

‘No one will sail there on a rough sea. We’ll wait for forensics before disturbing the ground.’ Madron rises to his feet, then glances at me. ‘I’ll ring Gannick and give her an update. No time-wasting, please, Kitto.’ He glowers at me, then disappears back into his lair.

‘Can we see your photos of the scene, boss?’ Isla’s voice is muted.

‘Of course, but nothing on the incident board. Okay?’

Isla studies the photos first, while Lawrie Deane peers over her shoulder, his expression horrified. It’s not surprising. There’s nothing in that ravaged face to offer us hope. The sergeant is always reliable, but his aversion to violence is well known. A sensitive soul must be lurking in there somewhere, behind his bluster and common sense.

All three members of my team look numb as they return to their desks. The victim may have been killed by an islander or a passing sailor. At times like this, the Atlantic seems much too wide to reveal a buried truth. We’ve never begun a case with so little evidence at our disposal and the weather against us. A fresh band of rain lashes the window, hard, as we set to work in silence.

6

Eddie’s face is lit with curiosity when we set off for the hospital at 6.00 pm. His shock seems to have worn off, leaving his appetite for work intact.

‘Why do you think she was buried there, boss?’

‘God knows, but only a psychopath would fire up a barbecue straight after burying a child.’

He studies me again. ‘I used to sail to St Helen’s with mates for a bit of freedom. Teenagers still do it now.’

‘Not in mid-winter, surely?’

‘The cold didn’t touch us back then. We just wanted to get drunk and chase girls.’ The memory makes him smile, until the subject darkens again. ‘This will stir up all the conspiracy crap the schoolkids are on about, won’t it?’

‘How do you mean?’