Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

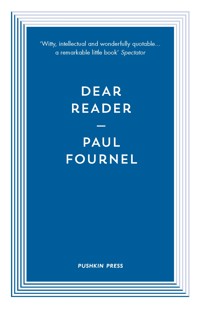

There's a lot of good to be said about publishing, mainly about the food. The books, though - Robert Dubois feels as if he's read the books, but still they keep coming back to him, the same old books just by new authors. Maybe he's ready to settle into the end of his career, like it's a tipsy afternoon after a working lunch. But then he is confronted with a gift: a piece of technology, a gizmo, a reader...Dear Reader takes a wry, affectionate look at the world of publishing, books and authors, and is a very funny, moving story about the passing of the old and the excitement of the new.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 176

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

There’s a pile of books that have to be read, that everybody’s read, that I’ve not read, probably because I thought that they’d been read sufficiently without needing me to read them as well; meanwhile I read other books.

—FRANÇOIS CARADEC

“No one knows what makes books sell.”

“I’ve heard that before,” Garp said.

—JOHN IRVING,

The World According to Garp

Contents

1

For a long time I would put my feet on it for a spot of rest and elevation and so as to improve circulation to the brain, but nowadays I find with increasing frequency that I lay my head on it, particularly in the evening, Friday evenings especially. I fold my arms around the manuscript, rest my forehead on the crook of my arm and my cheek on the virgin paper. The wood my desk is made of amplifies the sound of my heart. Well-aged art deco furniture makes an excellent conductor of feelings and fatigue. Is it a Ruhlmann? Or a piece from Leleu? My good old desk has seen it all. I listen to my heart, my Friday heart, my old heart beating in the silent house. At this hour everyone else has gone home and I’m the last man on deck, all alone on a losing streak because I haven’t had the heart to pile up the towering monument of manuscripts I have to take home for the weekend. Same as every Friday.

The one under my cheek has a love theme: it’s about a guy who meets a girl but he’s got a wife and she’s got a boyfriend… I’ve read seven pages and I know the rest already. Nothing’s going to give me a surprise any more. For years I’ve not really read anything, because all I do is reread. I spend my time rereading the same brew that gets served up as literary sensations, lead titles, seasonal launches, runaway successes, flops and more flops. Paper for pulping, in trucks that set off at dawn and return at dusk full to the gunwales of obsolete new books.

When was it exactly that I stopped jumping for joy at the mere thought that I might discover a masterpiece and come back into the office on a Monday morning a new man? Twenty years ago? Could it be thirty? I don’t like doing sums of that sort, they have a whiff of mortality about them. When I close my eyes the steady yellow glow of the Perzel lamp passes through my eyelids and summons up black whorls and floating ruins like a drawing by Victor Hugo. My breathing slows down as does my cardiac rhythm somewhat. I could easily drop off. I could die. Yes! Like Molière, I could die in the saddle. They’d say, “He died as he lived, among books, whilst reading!” and to be honest I would have passed on while dreaming of nothing. I haven’t really read properly for a long time. Do I still know how to read—I mean, to read in the full sense of the word? Am I still up to it? If I let my head loll to the side, my heart beats louder and sends a shiver through the oak…

The whole house is bathed in the silence of old paper. Books, like snow, gobble up sound. My profession has its own smell and mufflers. I can smell it better in this quiet. Going back into the noise of the world is always a challenge.

Who’s that knocking at my door? I don’t recognize that gentle, brief and polite taptaptap. The knuckle must be very small.

“Come in!”

She enters. I’ve never seen her before. A pang of nostalgia grips me, nostalgia for the good old days when the firm was small enough for me to know every girl in the office by the shape of her calves. This one has a nice face. Her wide-eyed stare suggests that mine is somewhat the worse for wear. Probably red pressure lines on my cheek from leaning it on my jacket sleeve.

“Am I interrupting?”

“Not fatally, young lady. Who are you?”

“Er, I’m the intern.”

“Which department?”

“I wasn’t told. You know, interns get lumbered with so much stuff, they have to be adaptable.”

“Do you want a raise?”

“No, I’m unpaid.”

She seems fairly startled, her jeans are torn and the rest of her chromatic. She’s short, has black eyes, looks nice, but I’d have a hard time telling if she’s pretty. I can’t read these kinds of girls either any more. She’s lively. Is she from Normale Sup’? Or from the College of Printing—the mill that churns out a thousand Gaston Gallimards a year, the better to pulp them later on?

“No. Arts Administration.”

“Really? You want to minister to publishing? I wish you the very best of luck.”

“I’d rather run concerts.”

“Sit down.”

“I can’t stay. It’s Friday. It’s late.”

“Five minutes. You want to run concerts?”

“Yeah, music is great.”

“So what are you doing here?”

“I like books as well! Anyway, there was an opening. We have to do a placement. Compulsory.”

“And if I may be so bold as to inquire, what are you doing in my office?”

“The big boss, Monsieur Meunier, told me to…”

“Is that what he’s called? Meunier?”

“Don’t you know him?”

“Only too well.”

“So you know. He told me to bring you this.”

“This being what, precisely?”

“Er, it’s a reader. A Kandle. An iClone. One of those gizmos. He said he’d put all your weekend manuscripts on it, it would take a weight off your shoulder. Do you want me to show you? Look, it’s like a screen with all your manuscripts on it. They’re on your genuine wood-style virtual bookshelf. One tap and they open. There’s a heap of them. You’re never going to get through all that in two days! Look, this is how you open a book.”

“How do I go to the next page?”

“You turn pages by sliding the corner on the bottom.”

“Like a book?”

“Yeah, that’s the prehistoric side of it. A sop for seniors. When people have forgotten about books they’ll wonder why it works that way. Vertical makes more sense. Scrolling down would be more logical.”

“Jack Kerouac will be pleased.”

She doesn’t get it.

“OK, I’m sorry, sir, I have to rush, I have a plane to catch. Don’t read too much!”

“At my age…”

She disappears in a jiggle of buttock, closes the door gently behind her, and leaves me stroking my reader. It’s black, cold, hostile and does not like me. There’s no protruding button, no handle to hold it by or to swing it around like a slender briefcase, it’s just hi-tech bling as classy as a Swedish brunette. Matt black or pitch dark (take your pick), smooth, soft, mirror-faced, and not heavy at all. I weigh it in my hand.

I put it on my desk and put my cheek on it. It’s cold, silent, doesn’t crumple or stain. There’s no sign that it’s got all those books in its belly. But it’s really inconvenient. It’s small enough to swim around in my briefcase, but too big to slip in my pocket.

In fact it has a lot in common with Meunier, the big boss. Not well suited to the task.

What was it the kid intern just said about books and concerts? In a way I’m going to have to let my briefcase go too, it’s become too big for the job. I’ve schlepped it around since I was in my last year at school, and parting is going to be hard on us both. We were really very fond of each other, even if we never said it out loud. When it was properly packed on a Friday night it felt just the right weight for work. It’s the reason why my left shoulder is slightly lower than the right. Workplace disability. Quasimodo.

What I’ll need now is a slipcase for my little reader. With a handle, if you please. I’m sure Meunier already has one in his desk drawer and that he’ll turn up with it in triumph on Monday morning, when he comes to gather my opinion of his great discovery. “You have to keep up with the times, Gaston!” He’s always liked calling me Gaston. Perhaps he thinks I like it too. Unless he thinks it’s a joke. I’m not a fool and I know his gift won’t be from Hermès or even Longchamp. I guess it will be some kind of mock croc with a foam lining to absorb knocks and bumps. Like the man himself.

I’m on my way, I have to be on my way. But let me stay behind another minute to lie on my desk—just for a minute—with my nose in a manuscript, so as to smell it one last time. For the truth about publishing is that the sensation in your nostrils can tell you as much about a book as an hour of close reading.

2

I cannot stand the countryside. That’s why I go there every weekend. So as to read and have a heart attack in enemy territory, in dark and lugubrious silence. As I gave up having a good night’s sleep long ago, I get out of bed in the pitch dark of the back of beyond and automatically dive into the thickest of my weekend doorstops. I sink onto the sofa, wrap my legs in a blanket, and read. My habitual technique is quite simple: I stack the pile of sheets on my paunch, and as I read I transfer them one by one to my chest. The increasing pressure on my ribcage gives an accurate reading of how much work I have done. For the first twenty pages I read with great attention, as slowly as I can make myself read, then I speed up gently, allowing my professional experience and what I know of the author and the book’s concept to take over—imagination does the rest. This is my semi-somnolent reading style, which constitutes my deepest mode of engagement with a text. It’s the perfect time for working on authors that the firm has published for many years—solid old troopers who need nothing more than a tuck or a nip.

The tablet is on my paunch. I hold it in both hands. There is a page open on the screen. I’ve matched the font size to the strength of my half-moons. The reader is cold to the touch. It’ll take a minute for my hands to warm it up. My reading lamp makes an unpleasant glare in one corner of the screen. I switch it off. Now the only light comes from the text. That’s a plus. If I look at myself in the mirror, with the tablet under my chin, I look like a ghost. I am the ghost of readers past.

With a flick of a finger I turn pages that don’t fall on any pile. They depart body and soul to some imaginary place I can hardly imagine. My chest is anxious and gives me no guide to how far I’ve got. There’s no noise of turning pages to break the silence of the house. I miss the slight breeze I used to feel on my neck from each page as it fell. I am hot. The light from the page absorbs my eyes. I’ve suddenly lost a character and I have to go back. My useless pencil is still behind my ear (I’m a bookie reader) and I’m puzzled as to how I’m going to keep track of typos. I’m really put off by the idea of summoning up a keyboard the way the intern showed me and barging into the text. I’ve always been a man of margins and lead pencils. I want to be erasable. For a second I rest the reader on my chest and close my eyes. I’m waiting for the screen to go to sleep so I can too, just for fifteen minutes, until dawn comes.

The second reading session of my ritual day is located in the café. As soon as it opens. The first ferrous double shot of the day is mine. An unchanging espresso hand-pumped by the unchanging Albert, whom I’ve known since our schooldays, a man of few words and striking habits.

*

“Are you schlepping a TV around with you these days?”

“As you can see.”

“No more reams?”

“I’m into crease-proof.”

“Here’s your poison. As soon as Marco opens up, I’ll fetch your croissant.”

As the café noise begins to increase bit by bit, it’s time for the kind of reading that bucks me up. The early birds come in for their doses of coffee-with-calvados or white wine spritzers. A slow start to the day. Saturday is long. This is when I read detective novels. The radio on a shelf behind the bar produces a background track mixing murders in and out of the sentences I’m reading. A merging of murders. I can usually distinguish which ones belong to the manuscript because I know how they end, but the others float off in a fog of endless beginnings. Albert leaves me alone and so do the others, because I’m part of the furniture and don’t make a noise. I keep it up until the card players arrive. Then the spasmodic sounds of new hands, ritual squabbles, and cards being called force me outside.

I’ve made a greasy stain on the screen. It must be from Marco’s croissant. Albert lends me his wet bar-rag to wipe it clean. I give it a dry finish with my sleeve and go out. I wonder whether the tablet is waterproof.

It’s the ideal time to go to my bench in the park. It’s not sunny. It’s not raining. It’s time for reading poems under the lime. I can’t manage to find them in this darned black box. I hunt all over the place to find my poems. It would be just like Meunier to hide them away. To warn me not to persist in the fantastical idea of bringing them out. “Another black hole, Gaston! Poetry is a bottomless pit!”

If the poems are any good, they make this the nicest part of the day. The temperature is on the rise, the kids are shouting off scale, I fold one leg under the other on the bench and I sing the poems to myself. Progress slows to a pitiable speed as I dawdle, go back on my tracks, hesitate, recite, and waste precious time. Vacation time, so to speak. I rest my dear reader in my lap, I look around. Soon I’m thinking of other poems, and then others beside. In a trice I’m thinking about nothing at all. I’m backing off.

Sometimes Adèle comes to join me. Over the years she’s learned exactly what time my mind begins to wander so she can slip in and winch me back home to normality. To the normality of people who read no more than one hour a day, the normality of the monumental Middle-aged Mother of Two, at whose oracular feet all publishers lay down their lists, their retail distribution arrangements and their promotional campaigns. Adèle usually comes from the other end of the park. When I see that head of white hair and the rubbery stride that’s no longer as bouncy as it was, I know it is time.

Today she’s not coming. She told me she wanted to sleep in, and as a result I’m lumbered with the shopping. I’ve not forgotten about it, but it means I’ll have to snap out of my daze all by myself. She even added that she’d wait until siesta time to filch my reader from me. She has clever fingers and a quick mind. Whereas I’m a slowcoach and stick to the tricks I know. A reader, yes, but an explorer, no.

“Say, René, would you mind weighing this for me?”

The butcher, an upright man in a bloody apron with his cleavers set criss-cross in pockets on his paunch, takes my reader without demur and puts it on the scales. The needle wobbles for a second.

“730 grams without the rind, Robert, my friend!”

“Or a bit over?”

“As always. Can I have a look at your toy? How do you switch it on?”

“Press on the dimple at the bottom.”

So that’s the final weight of world literature as it sits in René’s fat red fingers. 730 grams. Cervantes, Hugo, Dickens, and Proust make just 730 grams. Want to throw in Perec? 730 grams. Rilke as well? Just 730 grams.

“I’ll have two rump steaks, René.”

“Up and coming! Specially for you. Here, take your gizmo back. I put some blood on it. The kids are going to be after it. Can you watch TV on it?”

René slices two steaks with his forefingers folded on the side of the blade, a nice trick he learned from his father. He lays them on grease-proof paper as if they were old masters. Butchering doesn’t change. The knives are the same, the meat is the same. There’s no butchers’ revolution marching ever on.

“You see, René, you’ve got the joint on one side of you and the grease-proof paper on the other. Well, that’s how it is for me too. Text on one side and paper on the other. From now on they’re not permanently stuck together.”

I’m going to ask Marco the pastry chef to weigh my reader a second time, to confirm the true weight of world literature and the final demise of the doorstop. With a bit of luck, he’ll anoint it with a dollop of cream.

3

“What’s that sticking plaster on your nose? Did you get into a fight?”

“I fell asleep reading, and my dear reader toppled onto me. All seven hundred and thirty certified grams of it. Something like that really wakes you up. Another siesta ruined. My nose can take it. But I do have to admit that I keep squinting at the dressing… What’s on the menu for today?”

I like Sabine a lot. She’s a redhead. It would be a good idea for every firm to have a redhead on its staff. I like going into her office, which is next to mine. When I come in, she swings round on her chair to face me, as if we were going to have a fight. Actually, we have a game: I pretend not to know what’s on my plate, and she pretends to be in complete control of my schedule. She knows everything about me, and I know a fair bit about her too. On closer inspection, she runs the firm and loves to prove it. She used to be incredibly good-looking and now at thirty-something she is creditably handsome. How many writers stayed with us because of her? How many passionate affairs has she had? She has come through upheavals and lay-offs. On the day I hired her, maybe ten years ago, I remember thinking: “A character like that won’t last ten days, but I have to have someone.” That’s how much insight I have into the female of the species.

“The guys in production want to see you at 1:15, and then you’ve got Balmer for lunch.”

“Which eatery?”

“I made a reservation at the Tilbury. Is that OK?”

“As always. What does Balmer want?”

“Nothing. It’s just time to give him a kick in the pants. He got a big advance and Meunier’s worried about him taking it easy.”

“Meunier doesn’t know a pro from a purse. Balmer has always met his deadlines.”

“Many a time and oft…”

“Was that supposed to be a pun? Did you send the email to the Yanks?”

“Yes, boss.”

Mme Martin, the owner of the Tilbury, is exactly as old as Pauline Réage. In addition she can be held responsible for the waist measurements of most of my colleagues in French publishing. She serves heavy, slow-cooked food, like an ethnic granny in exile in the Valley of Books. It was because of her, I recall, that I nearly dropped the idea of launching my own company when I was a young man: the sight of my protuberant elders waddling ponderously around the publishing district gave me a real fright. I really had no wish to end up like them. Fortunately there were two notorious ascetics who balanced things out by performing lunch assignments with just a bottle of spring water. They were the Stone Commanders of the profession. Giacomettis. I took the plunge. When all’s said and done I haven’t made any money out of publishing but I have eaten rather well.