2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Delphi Publishing Ltd

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: Delphi Poets Series

- Sprache: Englisch

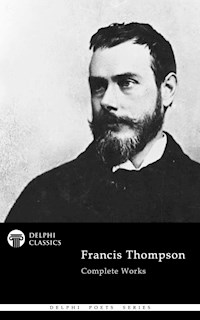

Francis Thompson was a visionary mystic poet of the late 1890’s, whose work is chiefly associated with rhapsodic accounts of religious experience influenced by seventeenth century Catholic verse. His most famous poem, ‘The Hound of Heaven’, which describes the pursuit of the human soul by God, won instant critical acclaim, securing its status as a classic of English poetry. Thompson also produced elegant and poignant short poems, including ‘At Lord’s’, a nostalgic elegy on the sport of cricket. The Delphi Poets Series offers readers the works of literature’s finest poets, with superior formatting. For the first time in digital publishing, this eBook offers Thompson’s complete works, with related illustrations and the usual Delphi bonus material. (Version 1)

* Beautifully illustrated with images relating to Thompson’s life and works

* Concise introduction to Thompson’s life and poetry

* The poems’ text is based on the authoritative Burns & Oates 1913 edition

* Excellent formatting of the poems

* Special chronological and alphabetical contents tables for the poetry

* Easily locate the poems you want to read

* Includes Thompson’s complete prose, including many rare essays published posthumously

* Features Everard Meynell’s seminal study of the poet’s life— discover Thompson’s intriguing life

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to see our wide range of poet titles

CONTENTS:

The Life and Poetry of Francis Thompson

Brief Introduction: Francis Thompson by Carroll B. Chilton

Complete Poetical Works of Francis Thompson

The Poems

List of Poems in Chronological Order

List of Poems in Alphabetical Order

The Prose

The Prose Works of Francis Thompson

The Biography

The Life of Francis Thompson, by Everard Meynell (1913)

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of poetry titles or buy the entire Delphi Poets Series as a Super Set

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1232

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Francis Thompson

(1859-1907)

Contents

The Life and Poetry of Francis Thompson

Brief Introduction: Francis Thompson by Carroll B. Chilton

Complete Poetical Works of Francis Thompson

The Poems

List of Poems in Chronological Order

List of Poems in Alphabetical Order

The Prose

The Prose Works of Francis Thompson

The Biography

The Life of Francis Thompson, by Everard Meynell (1913)

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2021

Version 1

Browse the entire series…

Francis Thompson

By Delphi Classics, 2021

COPYRIGHT

Francis Thompson - Delphi Poets Series

First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2021.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 91348 752 2

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

NOTE

When reading poetry on an eReader, it is advisable to use a small font size and landscape mode, which will allow the lines of poetry to display correctly.

The Life and Poetry of Francis Thompson

Late Victorian photograph of Preston, a city in Lancashire, England — Francis Thompson’s birthplace

Preston in recent times

The birthplace, Winckley Street, Preston

Memorial plaque to Thompson at his birthplace

Brief Introduction: Francis Thompson by Carroll B. Chilton

From ‘Catholic Encyclopaedia’, Volume 14

FRANCIS THOMPSON

Poet, b. at Preston, Lancashire, 18 Dec., 1859; d. in London, 13 Nov., 1907. He came from the middle classes, the classes great in imaginative poetry. His father was a provincial doctor; two paternal uncles dabbled in literature; he himself referred his heredity chiefly to his mother, who died in his boyhood. His parents being Catholics, he was educated at Ushaw, the college that had in former years Lingard, Waterton, and Wiseman as pupils. There he was noticeable for love of literature and neglect of games, though as spectator he always cared for cricket, and in later years remembered the players of his day with something like personal love. After seven years he went to Owens College to study medicine. He hated this proposed profession more than he would confess to his father; he evaded rather than rebelled, and finally disappeared. No blame, or attribution of hardships or neglect should attach to his father’s memory; every careful father knows his own anxieties. Francis Thompson went to London, and there endured three years of destitution that left him in a state of incipient disease. He was employed as bookselling agent, and at a shoemaker’s, but very briefly, and became a wanderer in London streets, earning a few pence by selling matches and calling cabs, often famished, often cold, receiving occasional alms; on one great day finding a sovereign on the footway, he was requested to come no more to a public library because he was too ragged. He was nevertheless able to compose a little— “Dream-Tryst”, written in memory of a child, and “Paganism Old and New”, with a few other pieces of verse and prose.

Having seen some numbers of a new Catholic magazine, “Merry England”, he sent these poems to the editor, Mr. Wilfrid Meynell, in 1888, giving his address at a post-office. The manuscripts were pigeonholed for a short time, but when Mr. Meynell read them he lost no time in writing to the sender a welcoming letter which was returned from the post-office. The only way then to reach him was to publish the essay and the poem, so that the author might see them and disclose himself. He did see them, and wrote to the editor giving his address at a chemist’s shop. Thither Mr. Meynell went, and was told that the poet owed a certain sum for opium, and was to be found hard by, selling matches. Having settled matters between the druggist and his client, Mr. Meynell wrote a pressing invitation to Thompson to call upon him. That day was the last of the poet’s destitution. He was never again friendless or without food, clothing, shelter, or fire. The first step was to restore him to better health and to overcome the opium habit. A doctor’s care, and some months at Storrington, Sussex, where he lived as a boarder at the Premonstratensian monastery, gave him a new hold upon life. It was there, entirely free temporarily from opium, that he began in earnest to write poetry. “Daisy” and the magnificent “Ode to the Setting Sun” were the first fruits. Mr. Meynell, finding him in better health but suffering from the loneliness of his life, brought him to London and established him near himself. Thenceforward with some changes to country air, he was either an inmate or a constant visitor until his death nineteen years later.

In the years from 1889 to 1896 Thompson wrote the poems contained in the three volumes, “Poems”, “Sister Songs”, and “New Poems”. In “Sister Songs” he celebrated his affection for the two elder of the little daughters of his host and more than brother; “Love in Dian’s Lap” was written in honour of Mrs. Meynell, and expressed the great attachment of his life; and in the same book “The Making of Viola” was composed for a younger child. At Mr. Meynell’s house Thompson met Mr. Garvin and Coventry Patmore, who soon became his friends, and whose great poetic and spiritual influence was thenceforth pre-eminent in all his writings, and Mrs. Meynell introduced him at Box Hill to George Meredith. Besides these his friendships were few. In the last weeks of his life he received great kindness from Mr. Wilfrid Blunt, in Sussex. During all these years Mr. Meynell encouraged him to practise journalism and to write essays, chiefly as a remedy for occasional melancholy. The essay on Shelley, published twenty years later and immediately famous, was amongst the earliest of these writings; “The Life of St. Ignatius” and “Health and Holiness” were produced subsequently.

Did Francis Thompson, unanimously hailed on the morrow of his death as a great poet, receive no full recognition during life? It was not altogether absent. Patmore, Traill, Mr. Garvin, and Mr. William Archer wrote, in the leading reviews, profoundly admiring studies of his poems. Public attention was not yet aroused. But that his greatness received no stinted praise, then and since, may be seen in a few citations following. Mr. Meynell, who perceived the quality of his genius when no other was aware of it, has written of him as “a poet of high thinking, of `celestial vision’, and of imaginings that found literary images of answering splendour”; Mr. Chesterton acclaimed him as “a great poet”, Mr. Fraill as “a poet of the first order”; Mr. William Archer, “It is no minor Caroline simper that he recalls, but the Jacobean Shakespeare”; Mr. Garvin, “the Hound of Heaven seems to us the most wonderful lyric in our language”; Burne-Jones, “Since Gabriel’s [Rossetti’s] `Blessed Damozel’ no mystical words have so touched me”; George Meredith, “A true poet, one of a small band”; Coventry Patmore, “the `Hound of Heaven’ is one of the very few great odes of which the language can boast”. Of the essays on Shelley (Dublin Review) a journalist wrote truly, “London is ringing with it”. Francis Thompson died, after receiving all the sacraments, in the excellent care of the Sisters of St. John and St. Elizabeth, aged forty-eight.

CARROLL B. CHILTON.

Thompson as a young man

The celebrated poet Alice Meynell in 1912. Meynell (1847-1922) was a British writer, editor, critic and suffragist. Thompson’s poems were first published in Wilfrid and Alice Meynell’s ‘Merry England’ and the Meynells became a supporter of Thompson.

Owens College (later The Victoria University of Manchester) was a university in Manchester — Thompson studied medicine here for nearly eight years. While excelling in essay writing, he took no interest in his medical studies; he had a passion for poetry and for watching cricket matches. He never practised as a doctor, and to escape the reproaches of his father, he tried to enlist as a soldier, but was rejected for his slightness of stature.

The front entrance of Charing Cross railway station in a nineteenth century print — in 1885 Thompson fled penniless to London, where he tried to make a living as a writer. He became addicted to opium and lived on the streets of Charing Cross, with the homeless and other addicts. A prostitute, whose identity he never revealed, befriended him and gave him lodgings. Thompson later described her in his poetry as his ‘saviour’.

Our Lady of England Priory in Storrington, West Sussex, is the former home of Roman Catholic priests belonging to a Community of Canons Regular of Prémontré — in 1888, after three years on the streets, the magazine editors, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell, recognised the value of Thompson’s work. They took him into their home and, concerned about his opium addiction which was at its height following his years on the streets, sent him to Our Lady of England Priory for recuperation; he stayed for a couple of years.

The 1893 first edition of Thompson’s first poetry collection, which included his most famous work, ‘The Hound of Heaven’

Coventry Patmore (1823-1896) was an English poet and critic best known for ‘The Angel in the House’, his narrative poem about the Victorian ideal of a happy marriage. Patmore was a firm supporter of Thompson’s work.

Wilfrid Blunt (1840-1922) was an English poet and writer. He and his wife, Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodlines through their farm, the Crabbet Arabian Stud. Blunt was a close friend of Thompson in his later years.

J. R. R. Tolkien in the 1940’s — Thompson was also an influence on Tolkien, who presented a paper on his work in 1914.

Complete Poetical Works of Francis Thompson

BURNS & OATES 1913 TEXT

Edited by Wilfrid Meynell

CONTENTS

A NOTE BY FRANCIS THOMPSON’S LITERARY EXECUTOR

Poems on Children

DAISY.

THE MAKING OF VIOLA.

TO MY GODCHILD FRANCIS M. W. M.

THE POPPY. To Monica.

TO MONICA THOUGHT DYING.

TO OLIVIA

LITTLE JESUS

Sister Songs

PREFACE

SISTER SONGS: AN OFFERING TO TWO SISTERS

THE PROEM

PART THE FIRST

PART THE SECOND

INSCRIPTION

Love in Dian’s Lap.

DEDICATION. TO WILFRID AND ALICE MEYNELL.

BEFORE HER PORTRAIT IN YOUTH.

TO A POET BREAKING SILENCE.

MANUS ANIMAM PINXIT.

A CARRIER SONG.

SCALA JACOBI PORTAQUE EBURNEA.

GILDED GOLD.

HER PORTRAIT.

EPILOGUE.

DOMUS TUA

IN HER PATHS

AFTER HER GOING

BENEATH A PHOTOGRAPH

The Hound of Heaven

THE HOUND OF HEAVEN.

Ode to the Setting Sun

ODE TO THE SETTING SUN

PRELUDE.

ODE.

AFTER-STRAIN.

A Corymbus for Autumn

A CORYMBUS FOR AUTUMN

To the Dead Cardinal of Westminster

TO THE DEAD CARDINAL OF WESTMINSTER.

Ecclesiastical Ballads

THE VETERAN OF HEAVEN.

LILLIUM REGIS.

Translations

A SUNSET

HEARD ON THE MOUNTAIN

AN ECHO OF VICTOR HUGO

Miscellaneous Poems

DREAM-TRYST.

ARAB LOVE SONG

BUONA NOTTE

THE PASSION OF MARY.

MESSAGES.

AT LORD’S

AT LORD’S (FINAL VERSION)

LOVE AND THE CHILD

DAPHNE

ABSENCE

TO W. M.

A FALLEN YEW.

A JUDGMENT IN HEAVEN.

THE SERE OF THE LEAF

TO STARS

LINES FOR A DRAWING OF OUR LADY OF THE NIGHT

ORISON-TRYST

WHERETO ART THOU COME?

SONG OF THE HOURS

PASTORAL

PAST THINKING OF

A DEAD ASTRONOMER

CHEATED ELSIE

THE FAIR INCONSTANT

THREATENED TEARS

THE HOUSE OF SORROWS

INSENTIENCE

ENVOY

New Poems

DEDICATION TO COVENTRY PATMORE

SIGHT AND INSIGHT

THE MISTRESS OF VISION.

CONTEMPLATION

‘BY REASON OF THY LAW’

THE DREAD OF HEIGHT

ORIENT ODE

NEW YEAR’S CHIMES.

FROM THE NIGHT OF FOREBEING AN ODE AFTER EASTER

ANY SAINT

ASSUMPTA MARIA

THE AFTER WOMAN

GRACE OF THE WAY

RETROSPECT

A Narrow Vessel

A NARROW VESSEL.

A GIRL’S SIN I. — IN HER EYES

A GIRL’S SIN II. — IN HIS EYES

LOVE DECLARED

THE WAY OF A MAID

BEGINNING OF END

PENELOPE

THE END OF IT

EPILOGUE

Ultima

LOVE’S ALMSMAN PLAINETH HIS FARE

A HOLOCAUST

BENEATH A PHOTOGRAPH

AFTER HER GOING

MY LADY THE TYRANNESS

UNTO THIS LAST

ULTIMUM

ENVOY

An Anthem of Earth

AN ANTHEM OF EARTH

Miscellaneous Odes

LAUS AMARA DOLORIS

A CAPTAIN OF SONG

AGAINST URANIA

TO THE ENGLISH MARTYRS

ODE FOR THE DIAMOND JUBILEE OF QUEEN VICTORIA, 1897

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

PEACE

CECIL RHODES

OF NATURE: LAUD AND PLAINT

Sonnets

AD AMICAM

TO A CHILD

HERMES

HOUSE OF BONDAGE

THE HEART

DESIDERIUM INDESIDERATUM

LOVE’S VARLETS

NON PAX-EXPECTATIO

NOT EVEN IN DREAM

Miscellaneous Poems

A HOLLOW WOOD

TO DAISIES

TO THE SINKING SUN

A MAY BURDEN

JULY FUGITIVE

FIELD-FLOWER

TO A SNOWFLAKE

A QUESTION

THE CLOUD’S SWAN-SONG

OF MY FRIEND

TO MONICA: AFTER NINE YEARS

TO MONICA: AFTER NINE YEARS

A DOUBLE NEED

GRIEF’S HARMONICS

MEMORAT MEMORIA

NOCTURN

HEAVEN AND HELL

CHOSE VUE

ST MONICA

MARRIAGE IN TWO MOODS

ALL FLESH

THE KINGDOM OF GOD

THE SINGER SAITH OF HIS SONG

Thompson in later years

A NOTE BY FRANCIS THOMPSON’S LITERARY EXECUTOR

IN making this Collection I have been governed by Francis Thompson’s express instructions, or guided by a knowledge of his feelings and preferences acquired during an unbroken intimacy of nineteen years. His own list of new inclusions and his own suggested reconsiderations of his formerly published text have been followed in this definitive edition of his Poetical Works.

May 1915. W. M.

Poems on Children

DAISY.

Where the thistle lifts a purple crown Six foot out of the turf,And the harebell shakes on the windy hill — O the breath of the distant surf! —

The hills look over on the South, And southward dreams the sea;And, with the sea-breeze hand in hand, Came innocence and she.

Where ‘mid the gorse the raspberry Red for the gatherer springs,Two children did we stray and talk Wise, idle, childish things.

She listened with big-lipped surprise, Breast-deep mid flower and spine:Her skin was like a grape, whose veins Run snow instead of wine.

She knew not those sweet words she spake, Nor knew her own sweet way;But there’s never a bird, so sweet a song Thronged in whose throat that day!

Oh, there were flowers in Storrington On the turf and on the spray;But the sweetest flower on Sussex hills Was the Daisy-flower that day!

Her beauty smoothed earth’s furrowed face! She gave me tokens three: — A look, a word of her winsome mouth, And a wild raspberry.

A berry red, a guileless look, A still word, — strings of sand!And yet they made my wild, wild heart Fly down to her little hand.

For standing artless as the air, And candid as the skies,She took the berries with her hand, And the love with her sweet eyes.

The fairest things have fleetest end: Their scent survives their close,But the rose’s scent is bitterness To him that loved the rose!

She looked a little wistfully, Then went her sunshine way: — The sea’s eye had a mist on it, And the leaves fell from the day.

She went her unremembering way, She went and left in meThe pang of all the partings gone, And partings yet to be.

She left me marvelling why my soul Was sad that she was glad;At all the sadness in the sweet, The sweetness in the sad.

Still, still I seemed to see her, still Look up with soft replies,And take the berries with her hand, And the love with her lovely eyes.

Nothing begins, and nothing ends, That is not paid with moan;For we are born in other’s pain, And perish in our own.

THE MAKING OF VIOLA.

I.

The Father of Heaven.

Spin, daughter Mary, spin,Twirl your wheel with silver din;Spin, daughter Mary, spin, Spin a tress for Viola.

Angels.

Spin, Queen Mary, aBrown tress for Viola!

II.

The Father of Heaven.

Weave, hands angelical,Weave a woof of flesh to pall — Weave, hands angelical — Flesh to pall our Viola.

Angels.

Weave, singing brothers, aVelvet flesh for Viola!

III.

The Father of Heaven.

Scoop, young Jesus, for her eyes,Wood-browned pools of Paradise — Young Jesus, for the eyes, For the eyes of Viola.

Angels.

Tint, Prince Jesus, aDuskèd eye for Viola!

IV.

The Father of Heaven.

Cast a star therein to drown,Like a torch in cavern brown,Sink a burning star to drown Whelmed in eyes of Viola.

Angels.

Lave, Prince Jesus, aStar in eyes of Viola!

V.

The Father of Heaven.

Breathe, Lord Paraclete,To a bubbled crystal meet — Breathe, Lord Paraclete — Crystal soul for Viola.

Angels.

Breathe, Regal Spirit, aFlashing soul for Viola!

VI.

The Father of Heaven.

Child-angels, from your wingsFall the roseal hoverings,Child-angels, from your wings, On the cheeks of Viola.

Angels.

Linger, rosy reflex, aQuenchless stain, on Viola!

All things being accomplished, saith the Father of Heaven.

Bear her down, and bearing, sing,Bear her down on spyless wing,Bear her down, and bearing, sing, With a sound of viola.

Angels.

Music as her name is, aSweet sound of Viola!

VIII.

Wheeling angels, past espial,Danced her down with sound of viol;Wheeling angels, past espial, Descanting on “Viola.”

Angels.

Sing, in our footing, aLovely lilt of “Viola!”

IX.

Baby smiled, mother wailed,Earthward while the sweetling sailed;Mother smiled, baby wailed, When to earth came Viola.

And her elders shall say: —

So soon have we taught you aWay to weep, poor Viola!

X.

Smile, sweet baby, smile,For you will have weeping-while;Native in your Heaven is smile, — But your weeping, Viola?

Whence your smiles we know, but ah?Whence your weeping, Viola? — Our first gift to you is aGift of tears, my Viola!

TO MY GODCHILD FRANCIS M. W. M.

This labouring, vast, Tellurian galleon,Riding at anchor off the orient sun,Had broken its cable, and stood out to spaceDown some frore Arctic of the aërial ways:And now, back warping from the inclement main,Its vaporous shroudage drenched with icy rain,It swung into its azure roads again;When, floated on the prosperous sun-gale, youLit, a white halcyon auspice, ‘mid our frozen crew.

To the Sun, stranger, surely you belong,Giver of golden days and golden song;Nor is it by an all-unhappy planYou bear the name of me, his constant Magian.Yet ah! from any other that it came,Lest fated to my fate you be, as to my name.When at the first those tidings did they bring,My heart turned troubled at the ominous thing:Though well may such a title him endower,For whom a poet’s prayer implores a poet’s power.The Assisian, who kept plighted faith to three,To Song, to Sanctitude, and Poverty,(In two alone of whom most singers proveA fatal faithfulness of during love!);He the sweet Sales, of whom we scarcely kenHow God he could love more, he so loved men;The crown and crowned of Laura and Italy;And Fletcher’s fellow — from these, and not from me,Take you your name, and take your legacy!

Or, if a right successive you declareWhen worms, for ivies, intertwine my hair,Take but this Poesy that now followethMy clayey hest with sullen servile breath,Made then your happy freedman by testating death.My song I do but hold for you in trust,I ask you but to blossom from my dust.When you have compassed all weak I began,Diviner poet, and ah! diviner man;The man at feud with the perduring childIn you before song’s altar nobly reconciled;From the wise heavens I half shall smile to seeHow little a world, which owned you, needed me.If, while you keep the vigils of the night,For your wild tears make darkness all too bright,Some lone orb through your lonely window peeps,As it played lover over your sweet sleeps;Think it a golden crevice in the sky,Which I have pierced but to behold you by!

And when, immortal mortal, droops your head,And you, the child of deathless song, are dead;Then, as you search with unaccustomed glanceThe ranks of Paradise for my countenance,Turn not your tread along the Uranian sodAmong the bearded counsellors of God;For if in Eden as on earth are we,I sure shall keep a younger company:Pass where beneath their rangèd gonfalonsThe starry cohorts shake their shielded suns,The dreadful mass of their enridgèd spears;Pass where majestical the eternal peers,The stately choice of the great Saintdom, meet — A silvern segregation, globed completeIn sandalled shadow of the Triune feet;Pass by where wait, young poet-wayfarer,Your cousined clusters, emulous to shareWith you the roseal lightnings burning ‘mid their hair;Pass the crystalline sea, the Lampads seven: — Look for me in the nurseries of Heaven.

THE POPPY. To Monica.

Summer set lip to earth’s bosom bare.And left the flushed print in a poppy there:Like a yawn of fire from the grass it came,And the fanning wind puffed it to flapping flame.

With burnt mouth red like a lion’s it drankThe blood of the sun as he slaughtered sank,And dipped its cup in the purpurate shineWhen the eastern conduits ran with wine.

Till it grew lethargied with fierce bliss,And hot as a swinked gipsy is,And drowsed in sleepy savageries,With mouth wide a-pout for a sultry kiss.

A child and man paced side by side,Treading the skirts of eventide;But between the clasp of his hand and hersLay, felt not, twenty withered years.

She turned, with the rout of her dusk South hair,And saw the sleeping gipsy there;And snatched and snapped it in swift child’s whim,With— “Keep it, long as you live!” — to him.

And his smile, as nymphs from their laving meres,Trembled up from a bath of tears;And joy, like a mew sea-rocked apart,Tossed on the wave of his troubled heart.

For he saw what she did not see,That — as kindled by its own fervency — The verge shrivelled inward smoulderingly:

And suddenly ‘twixt his hand and hersHe knew the twenty withered years — No flower, but twenty shrivelled years.

“Was never such thing until this hour,”Low to his heart he said; “the flowerOf sleep brings wakening to me,And of oblivion memory.”

“Was never this thing to me,” he said,“Though with bruisèd poppies my feet are red!”And again to his own heart very low:“O child! I love, for I love and know;

“But you, who love nor know at allThe diverse chambers in Love’s guest-hall,Where some rise early, few sit long:In how differing accents hear the throngHis great Pentecostal tongue;

“Who know not love from amity,Nor my reported self from me;A fair fit gift is this, meseems,You give — this withering flower of dreams.

“O frankly fickle, and fickly true,Do you know what the days will do to you?To your Love and you what the days will do,O frankly fickle, and fickly true?

“You have loved me, Fair, three lives — or days:‘Twill pass with the passing of my face.But where I go, your face goes too,To watch lest I play false to you.

“I am but, my sweet, your foster-lover,Knowing well when certain years are overYou vanish from me to another;Yet I know, and love, like the foster-mother.

“So, frankly fickle, and fickly true!For my brief life — while I take from youThis token, fair and fit, meseems,For me — this withering flower of dreams.”

* * * * * * *

The sleep-flower sways in the wheat its head,Heavy with dreams, as that with bread:The goodly grain and the sun-flushed sleeperThe reaper reaps, and Time the reaper.

I hang ‘mid men my needless head,And my fruit is dreams, as theirs is bread:The goodly men and the sun-hazed sleeperTime shall reap, but after the reaperThe world shall glean of me, me the sleeper!

Love! love! your flower of withered dreamIn leavèd rhyme lies safe, I deem,Sheltered and shut in a nook of rhyme,From the reaper man, and his reaper Time.

Love! I fall into the claws of Time:But lasts within a leavèd rhymeAll that the world of me esteems — My withered dreams, my withered dreams.

TO MONICA THOUGHT DYING.

You, O the piteous you! Who all the long night through Anticipatedly Disclose yourself to me Already in the waysBeyond our human comfortable days; How can you deem what Death Impitiably saith To me, who listening wake For your poor sake? When a grown woman diesYou know we think unceasinglyWhat things she said, how sweet, how wise;And these do make our misery. But you were (you to meThe dead anticipatedly!)You — eleven years, was’t not, or so? — Were just a child, you know; And so you never saidThings sweet immeditatably and wiseTo interdict from closure my wet eyes: But foolish things, my dead, my dead! Little and laughable, Your age that fitted well.And was it such things all unmemorable, Was it such things could makeMe sob all night for your implacable sake?

Yet, as you said to me,In pretty make-believe of revelry, So the night long said Death With his magniloquent breath; (And that remembered laughterWhich in our daily uses followed after,Was all untuned to pity and to awe): “A cup of chocolate, One farthing is the rate, You drink it through a straw.”

How could I know, how knowThose laughing words when drenched with sobbing so?Another voice than yours, than yours, he hath! My dear, was’t worth his breath,His mighty utterance? — yet he saith, and saith!This dreadful Death to his own dreadfulness Doth dreadful wrong,This dreadful childish babble on his tongue!That iron tongue made to speak sentences,And wisdom insupportably complete,Why should it only say the long night through, In mimicry of you, — “A cup of chocolate, One farthing is the rate,You drink it through a straw, a straw, a straw!” Oh, of all sentences, Piercingly incomplete!Why did you teach that fatal mouth to draw, Child, impermissible awe, From your old trivialness? Why have you done me this Most unsustainable wrong, And into Death’s controlBetrayed the secret places of my soul? Teaching him that his lips,Uttering their native earthquake and eclipse, Could never so availTo rend from hem to hem the ultimate veil Of this most desolateSpirit, and leave it stripped and desecrate, — Nay, never so have wrungFrom eyes and speech weakness unmanned, unmeet;As when his terrible dotage to repeatIts little lesson learneth at your feet; As when he sits among His sepulchres, to playWith broken toys your hand has cast away,With derelict trinkets of the darling young.Why have you taught — that he might so complete His awful panoply From your cast playthings — why,This dreadful childish babble to his tongue, Dreadful and sweet?

TO OLIVIA

I fear to love thee, Sweet, because Love’s the ambassador of loss; White flake of childhood, clinging so To my soiled raiment, thy shy snow At tenderest touch will shrink and go. Love me not, delightful child. My heart, by many snares beguiled, Has grown timorous and wild. It would fear thee not at all, Wert thou not so harmless-small. Because thy arrows, not yet dire, Are still unbarbed with destined fire, I fear thee more than hadst thou stood Full-panoplied in womanhood.

LITTLE JESUS

‘Ex Ore Infantium’

LITTLE Jesus, wast Thou shyOnce, and just so small as I?And what did it feel like to beOut of Heaven, and just like me?Didst Thou sometimes think of there,And ask where all the angels were?I should think that I would cryFor my house all made of sky;I would look about the air,And wonder where my angels were;And at waking ’twould distress me — Not an angel there to dress me!

Hadst Thou ever any toys,Like us little girls and boys?And didst Thou play in Heaven with allThe angels that were not too tall,With stars for marbles? Did the thingsPlay Can you see me? through their wings?And did thy Mother let Thee spoilThy robes, with playing on our soil?How nice to have them always newIn Heaven, because ’twas quite clean blue!

Didst Thou kneel at night to pray,And didst Thou join thy hands, this way?And did they tire sometimes, being young,And make the prayer seem very long?And dost Thou like it best, that weShould join our hands to pray to Thee?I used to think, before I knew,The prayer not said unless we do. And did thy Mother at the nightKiss Thee, and fold the clothes in right?And didst Thou feel quite good in bed,Kiss’d, and sweet, and thy prayers said?

Thou canst not have forgotten allThat it feels like to be small:And Thou know’st I cannot prayTo Thee in my father’s way — When Thou wast so little, say,Couldst Thou talk thy Father’s way?So, a little Child, come downAnd hear a child’s tongue like thy own;Take me by the hand and walk,And listen to my baby-talk.To thy Father show my prayer(He will look, Thou art so fair),And say: ‘O Father, I, thy Son,Bring the prayer of a little one.’

And He will smile, that children’s tongueHas not changed since Thou wast young!

Sister Songs

An Offering to Two Sisters

PREFACE

This poem, though new in the sense of being now for the first time printed, was written some four years ago, about the same date as the Hound of Heaven in my former volume.

One image in the Proem was an unconscious plagiarism from the beautiful image in Mr. Patmore’s St. Valentine’s Day: —

“O baby Spring,That flutter’st sudden ‘neath the breast of Earth,A month before the birth!”

Finding I could not disengage it without injury to the passage in which it is embedded, I have preferred to leave it, with this acknowledgment to a Poet rich enough to lend to the poor.

FRANCIS THOMPSON.

1895.

ToMonica and Madeline (Sylvia) Meynell

SISTER SONGS: AN OFFERING TO TWO SISTERS

THE PROEM

Shrewd winds and shrill — were these the speech of May? A ragged, slag-grey sky — invested so, Mary’s spoilt nursling! wert thou wont to go? Or thou, Sun-god and song-god, sayCould singer pipe one tiniest linnet-lay, While Song did turn away his face from song? Or who could be In spirit or in body hale for long, — Old Æsculap’s best Master! — lacking thee? At length, then, thou art here! On the earth’s lethèd ear Thy voice of light rings out exultant, strong;Through dreams she stirs and murmurs at that summons dear: From its red leash my heart strains tamelessly,For Spring leaps in the womb of the young year! Nay, was it not brought forth before, And we waited, to behold it, Till the sun’s hand should unfold it, What the year’s young bosom bore?Even so; it came, nor knew we that it came, In the sun’s eclipse. Yet the birds have plighted vows,And from the branches pipe each other’s name; Yet the season all the boughs Has kindled to the finger-tips, — Mark yonder, how the long laburnum dripsIts jocund spilth of fire, its honey of wild flame!Yea, and myself put on swift quickening,And answer to the presence of a sudden Spring.From cloud-zoned pinnacles of the secret spirit Song falls precipitant in dizzying streams;And, like a mountain-hold when war-shouts stir it,The mind’s recessèd fastness casts to lightIts gleaming multitudes, that from every height Unfurl the flaming of a thousand dreams.Now therefore, thou who bring’st the year to birth, Who guid’st the bare and dabbled feet of May;Sweet stem to that rose Christ, who from the earthSuck’st our poor prayers, conveying them to Him; Be aidant, tender Lady, to my lay! Of thy two maidens somewhat must I say,Ere shadowy twilight lashes, drooping, dim Day’s dreamy eyes from us; Ere eve has struck and furledThe beamy-textured tent transpicuous, Of webbèd coerule wrought and woven calms, Whence has paced forth the lambent-footed sun.And Thou disclose my flower of song upcurled, Who from Thy fair irradiant palms Scatterest all love and loveliness as alms; Yea, Holy One,Who coin’st Thyself to beauty for the world!

Then, Spring’s little children, your lauds do ye upraiseTo Sylvia, O Sylvia, her sweet, feat ways! Your lovesome labours lay away, And trick you out in holiday, For syllabling to Sylvia;And all you birds on branches, lave your mouths with May, To bear with me this burthen, For singing to Sylvia.

PART THE FIRST

The leaves dance, the leaves sing,The leaves dance in the breath of the Spring. I bid them dance, I bid them sing, For the limpid glance Of my ladyling;For the gift to the Spring of a dewier spring,For God’s good grace of this ladyling!I know in the lane, by the hedgerow track, The long, broad grasses underneathAre warted with rain like a toad’s knobbed back; But here May weareth a rainless wreath.In the new-sucked milk of the sun’s bosomIs dabbled the mouth of the daisy-blossom; The smouldering rosebud chars through its sheath;The lily stirs her snowy limbs, Ere she swimsNaked up through her cloven green,Like the wave-born Lady of Love Hellene;And the scattered snowdrop exquisite Twinkles and gleams, As if the showers of the sunny beamsWere splashed from the earth in drops of light. Everything That is child of Spring Casts its bud or blossomingUpon the stream of my delight.

Their voices, that scents are, now let them upraiseTo Sylvia, O Sylvia, her sweet, feat ways! Their lovely mother them array, And prank them out in holiday, For syllabling to Sylvia;And all the birds on branches lave their mouths with May, To bear with me this burthen, For singing to Sylvia.

While thus I stood in mazes bound Of vernal sorcery,I heard a dainty dubious sound, As of goodly melody;Which first was faint as if in swound, Then burst so suddenlyIn warring concord all around, That, whence this thing might be, To seeThe very marrow longed in me! It seemed of air, it seemed of ground, And never any witchery Drawn from pipe, or reed, or string, Made such dulcet ravishing. ’Twas like no earthly instrument, Yet had something of them all In its rise, and in its fall;As if in one sweet consort there were blent Those archetypes celestialWhich our endeavouring instruments recall. So heavenly flutes made murmurous plain To heavenly viols, that again — Aching with music — wailed back pain; Regals release their notes, which rise Welling, like tears from heart to eyes; And the harp thrills with thronging sighs. Horns in mellow flattering Parley with the cithern-string: — Hark! — the floating, long-drawn note Woos the throbbing cithern-string!

Their pretty, pretty prating those citherns sure upraiseFor homage unto Sylvia, her sweet, feat ways: Those flutes do flute their vowelled lay, Their lovely languid language say, For lisping to Sylvia;Those viols’ lissom bowings break the heart of May, And harps harp their burthen, For singing to Sylvia.

3.

Now at that music and that mirth Rose, as ‘twere, veils from earth; And I spied How beside Bud, bell, bloom, an elf Stood, or was the flower itself ‘Mid radiant air All the fair Frequence swayed in irised wavers. Some against the gleaming rims Their bosoms prest Of the kingcups, to the brims Filled with sun, and their white limbs Bathèd in those golden lavers; Some on the brown, glowing breast Of that Indian maid, the pansy, (Through its tenuous veils confest Of swathing light), in a quaint fancy Tied her knot of yellow favours; Others dared open draw Snapdragon’s dreadful jaw: Some, just sprung from out the soil, Sleeked and shook their rumpled fans Dropt with sheen Of moony green; Others, not yet extricate, On their hands leaned their weight, And writhed them free with mickle toil, Still folded in their veiny vans: And all with an unsought accord Sang together from the sward; Whence had come, and from sprites Yet unseen, those delights, As of tempered musics blent, Which had given me such content. For haply our best instrument, Pipe or cithern, stopped or strung, Mimics but some spirit tongue.

Their amiable voices, I bid them upraiseTo Sylvia, O Sylvia, her sweet, feat ways; Their lovesome labours laid away, To linger out this holidayIn syllabling to Sylvia;While all the birds on branches lave their mouths with May,To bear with me this burthen, For singing to Sylvia.

4.

Next I saw, wonder-whist, How from the atmosphere a mist, So it seemed, slow uprist; And, looking from those elfin swarms, I was ‘ware How the air Was all populous with forms Of the Hours, floating down, Like Nereids through a watery town. Some, with languors of waved arms, Fluctuous oared their flexile way; Some were borne half resupineOn the aërial hyaline,Their fluid limbs and rare arrayFlickering on the wind, as quiversTrailing weed in running rivers;And others, in far prospect seen,Newly loosed on this terrene, Shot in piercing swiftness came, With hair a-stream like pale and goblin flame. As crystálline ice in water, Lay in air each faint daughter; Inseparate (or but separate dim) Circumfused wind from wind-like vest, Wind-like vest from wind-like limb. But outward from each lucid breast, When some passion left its haunt, Radiate surge of colour came, Diffusing blush-wise, palpitant, Dying all the filmy frame. With some sweet tenderness they wouldTurn to an amber-clear and glossy gold; Or a fine sorrow, lovely to behold,Would sweep them as the sun and wind’s joined flood Sweeps a greening-sapphire sea; Or they would glow enamouredlyIllustrious sanguine, like a grape of blood;Or with mantling poetryCurd to the tincture which the opal hath,Like rainbows thawing in a moonbeam bath.So paled they, flushed they, swam they, sang melodiously.

Their chanting, soon fading, let them, too, upraiseFor homage unto Sylvia, her sweet, feat ways; Weave with suave float their wavèd way, And colours take of holiday, For syllabling to Sylvia;And all the birds on branches lave their mouths with May, To bear with me this burthen, For singing to Sylvia.

5.

Then, through those translucencies, As grew my senses clearer clear, Did I see, and did I hear, How under an elm’s canopy Wheeled a flight of Dryades Murmuring measured melody. Gyre in gyre their treading was, Wheeling with an adverse flight, In twi-circle o’er the grass, These to left, and those to right; All the band Linkèd by each other’s hand; Decked in raiment stainèd as The blue-helmèd aconite. And they advance with flutter, with grace, To the dance Moving on with a dainty pace, As blossoms mince it on river swells. Over their heads their cymbals shine, Round each ankle gleams a twine Of twinkling bells — Tune twirled golden from their cells. Every step was a tinkling sound, As they glanced in their dancing-ground, Clouds in cluster with such a sailing Float o’er the light of the wasting moon, As the cloud of their gliding veiling Swung in the sway of the dancing-tune. There was the clash of their cymbals clanging, Ringing of swinging bells clinging their feet; And the clang on wing it seemed a-hanging, Hovering round their dancing so fleet. — I stirred, I rustled more than meet; Whereat they broke to the left and right, With eddying robes like aconite Blue of helm; And I beheld to the foot o’ the elm.

They have not tripped those dances, betrayed to my gaze,To glad the heart of Sylvia, beholding of their maze; Through barky walls have slid away, And tricked them in their holiday, For other than for Sylvia;While all the birds on branches lave their mouths with May, And bear with me this burthen, For singing to Sylvia.

6.

Where its umbrage was enrooted, Sat white-suited, Sat green-amiced, and bare-footed, Spring amid her minstrelsy; There she sat amid her ladies, Where the shade is Sheen as Enna mead ere Hades’ Gloom fell thwart Persephone. Dewy buds were interstrown Through her tresses hanging down, And her feet Were most sweet, Tinged like sea-stars, rosied brown.A throng of children like to flowers were sownAbout the grass beside, or clomb her knee:I looked who were that favoured company. And one there stood Against the beamy floodOf sinking day, which, pouring its abundance,Sublimed the illuminous and volute redundanceOf locks that, half dissolving, floated round her face; As see I might Far off a lily-cluster poised in sun Dispread its gracile curls of light I knew what chosen child was there in place! I knew there might no brows be, save of one, With such Hesperian fulgence compassèd,Which in her moving seemed to wheel about her head.

O Spring’s little children, more loud your lauds upraise,For this is even Sylvia, with her sweet, feat ways! Your lovesome labours lay away, And prank you out in holiday, For syllabling to Sylvia;And all you birds on branches, lave your mouths with May, To bear with me this burthenFor singing to Sylvia!

7.

Spring, goddess, is it thou, desirèd long?And art thou girded round with this young train? — If ever I did do thee ease in song,Now of thy grace let me one meed obtain, And list thou to one plain. Oh, keep still in thy trainAfter the years when others therefrom fade, This tiny, well-belovèd maid!To whom the gate of my heart’s fortalice, With all which in it is,And the shy self who doth therein immew him‘Gainst what loud leagurers battailously woo him, I, bribèd traitor to him, Set open for one kiss.

Then suffer, Spring, thy children, that lauds they should upraiseTo Sylvia, this Sylvia, her sweet, feat ways; Their lovely labours lay away, And trick them out in holiday, For syllabling to Sylvia;And that all birds on branches lave their mouths with May, To bear with me this burthen, For singing to Sylvia.

8.

A kiss? for a child’s kiss? Aye, goddess, even for this. Once, bright Sylviola! in days not far,Once — in that nightmare-time which still doth hauntMy dreams, a grim, unbidden visitant — Forlorn, and faint, and stark,I had endured through watches of the dark The abashless inquisition of each star,Yea, was the outcast mark Of all those heavenly passers’ scrutiny; Stood bound and helplesslyFor Time to shoot his barbèd minutes at me;Suffered the trampling hoof of every hour In night’s slow-wheelèd car; Until the tardy dawn dragged me at length From under those dread wheels; and, bled of strength, I waited the inevitable last. Then there came pastA child; like thee, a spring-flower; but a flowerFallen from the budded coronal of Spring,And through the city-streets blown withering.She passed, — O brave, sad, lovingest, tender thing! — And of her own scant pittance did she give, That I might eat and live:Then fled, a swift and trackless fugitive. Therefore I kissed in theeThe heart of Childhood, so divine for me; And her, through what sore ways, And what unchildish days,Borne from me now, as then, a trackless fugitive. Therefore I kissed in thee Her, child! and innocency,And spring, and all things that have gone from me, And that shall never be;All vanished hopes, and all most hopeless bliss, Came with thee to my kiss.And ah! so long myself had strayed afarFrom child, and woman, and the boon earth’s green,And all wherewith life’s face is fair beseen; Journeying its journey bareFive suns, except of the all-kissing sun Unkissed of one; Almost I had forgot The healing harms,And whitest witchery, a-lurk in thatAuthentic cestus of two girdling arms: And I remembered not The subtle sanctities which dartFrom childish lips’ unvalued precious brush,Nor how it makes the sudden lilies push Between the loosening fibres of the heart. Then, that thy little kiss Should be to me all this,Let workaday wisdom blink sage lids thereat;Which towers a flight three hedgerows high, poor bat! And straightway charts me out the empyreal air.Its chart I wing not by, its canon of worthScorn not, nor reck though mine should breed it mirth:And howso thou and I may be disjoint,Yet still my falcon spirit makes her point Over the covert whereThou, sweetest quarry, hast put in from her!

(Soul, hush these sad numbers, too sad to upraiseIn hymning bright Sylvia, unlearn’d in such ways! Our mournful moods lay we away, And prank our thoughts in holiday, For syllabling to Sylvia;When all the birds on branches lave their mouths with May, To bear with us this burthen, For singing to Sylvia!)

9.

Then thus Spring, bounteous lady, made reply:“O lover of me and all my progeny, For grace to youI take her ever to my retinue.Over thy form, dear child, alas! my artCannot prevail; but mine immortalising Touch I lay upon thy heart. Thy soul’s fair shapeIn my unfading mantle’s green I drape,And thy white mind shall rest by my devising A Gideon-fleece amid life’s dusty drouth.If Even burst yon globèd yellow grape(Which is the sun to mortals’ sealèd sight) Against her stainèd mouth; Or if white-handed lightDraw thee yet dripping from the quiet pools, Still lucencies and cools,Of sleep, which all night mirror constellate dreams;Like to the sign which led the Israelite, Thy soul, through day or dark,A visible brightness on the chosen ark Of thy sweet body and pure, Shall it assure,With auspice large and tutelary gleams,Appointed solemn courts, and covenanted streams.”

Cease, Spring’s little children, now cease your lauds to raise;That dream is past, and Sylvia, with her sweet, feat ways. Our lovèd labour, laid away, Is smoothly ended; said our say, Our syllable to Sylvia.Make sweet, you birds on branches! make sweet your mouths with May! But borne is this burthen, Sung unto Sylvia.

PART THE SECOND

And now, thou elder nursling of the nest; Ere all the intertangled west Be one magnificenceOf multitudinous blossoms that o’errunThe flaming brazen bowl o’ the burnished sun Which they do flower from,How shall I ‘stablish thy memorial?Nay, how or with what countenance shall I come To plead in my defence For loving thee at all?I who can scarcely speak my fellows’ speech,Love their love, or mine own love to them teach;A bastard barred from their inheritance, Who seem, in this dim shape’s uneasy nook,Some sun-flower’s spirit which by luckless chance Has mournfully its tenement mistook;When it were better in its right abode,Heartless and happy lackeying its god.How com’st thou, little tender thing of white,Whose very touch full scantly me beseems,How com’st thou resting on my vaporous dreams, Kindling a wraith there of earth’s vernal green? Even so as I have seen, In night’s aërial sea with no wind blust’rous,A ribbèd tract of cloudy malachite Curve a shored crescent wide;And on its slope marge shelving to the night The stranded moon lay quivering like a lustrous Medusa newly washed up from the tide,Lay in an oozy pool of its own deliquious light.

Yet hear how my excuses may prevail, Nor, tender white orb, be thou opposite!Life and life’s beauty only hold their revelsIn the abysmal ocean’s luminous levels. There, like the phantasms of a poet pale,The exquisite marvels sail:Clarified silver; greens and azures frailAs if the colours sighed themselves away,And blent in supersubtile interplay As if they swooned into each other’s arms; Repured vermilion, Like ear-tips ‘gainst the sun;And beings that, under night’s swart pinion,Make every wave upon the harbour-bars A beaten yolk of stars.But where day’s glance turns baffled from the deeps, Die out those lovely swarms;And in the immense profound no creature glides or creeps.

Love and love’s beauty only hold their revelsIn life’s familiar, penetrable levels: What of its ocean-floor? I dwell there evermore. From almost earliest youth I raised the lids o’ the truth,And forced her bend on me her shrinking sight;Ever I knew me Beauty’s eremite, In antre of this lowly body set. Girt with a thirsty solitude of soul. Nathless I not forgetHow I have, even as the anchorite, I too, imperishing essences that console.Under my ruined passions, fallen and sere, The wild dreams stir like little radiant girls,Whom in the moulted plumage of the year Their comrades sweet have buried to the curls.Yet, though their dedicated amorist,How often do I bid my visions hist, Deaf to them, pleading all their piteous fills;Who weep, as weep the maidens of the mist Clinging the necks of the unheeding hills:And their tears wash them lovelier than before,That from grief’s self our sad delight grows more,Fair are the soul’s uncrispèd calms, indeed, Endiapered with many a spiritual form Of blosmy-tinctured weed;But scarce itself is conscious of the store Suckled by it, and only after stormCasts up its loosened thoughts upon the shore. To this end my deeps are stirred; And I deem well why life unshared Was ordainèd me of yore. In pairing-time, we know, the bird Kindles to its deepmost splendour, And the tender Voice is tenderest in its throat; Were its love, for ever nigh it, Never by it, It might keep a vernal note, The crocean and amethystine In their pristine Lustre linger on its coat. Therefore must my song-bower lone be, That my tone be Fresh with dewy pain alway; She, who scorns my dearest care ta’en, An uncertain Shadow of the sprite of May. And is my song sweet, as they say?’Tis sweet for one whose voice has no reply, Save silence’s sad cry:And are its plumes a burning bright array?They burn for an unincarnated eyeA bubble, charioteered by the inward breath Which, ardorous for its own invisible lure,Urges me glittering to aërial death, I am rapt towards that bodiless paramour;Blindly the uncomprehended tyranny Obeying of my heart’s impetuous might. The earth and all its planetary kin,Starry buds tangled in the whirling hairThat flames round the Phoebean wassailer, Speed no more ignorant, more predestined flight, Than I, her viewless tresses netted in.As some most beautiful one, with lovely taunting,Her eyes of guileless guile o’ercanopies, Does her hid visage bow,And miserly your covetous gaze allow, By inchmeal, coy degrees, Saying— “Can you see me now?”Yet from the mouth’s reflex you guess the wanting Smile of the coming eyesIn all their upturned grievous witcheries, Before that sunbreak rise;And each still hidden feature view withinYour mind, as eager scrutinies detailThe moon’s young rondure through the shamefast veil Drawn to her gleaming chin: After this wise,From the enticing smile of earth and skiesI dream my unknown Fair’s refusèd gaze;And guessingly her love’s close traits devise, Which she with subtile coquetriesThrough little human glimpses slow displays, Cozening my mateless days By sick, intolerable delays.And so I keep mine uncompanioned ways;And so my touch, to golden poesiesTurning love’s bread, is bought at hunger’s price.So, — in the inextinguishable warsWhich roll song’s Orient on the sullen nightWhose ragged banners in their own despiteTake on the tinges of the hated light, — So Sultan Phoebus has his Janizars.But if mine unappeasèd cicatrices Might get them lawful ease;Were any gentle passion hallowed me, Who must none other breath of passion feel Save such as winnows to the fledgèd heel The tremulous Paradisal plumages; The conscious sacramental trees Which ever be Shaken celestially,Consentient with enamoured wings, might know my love for thee.Yet is there more, whereat none guesseth, love! Upon the ending of my deadly night(Whereof thou hast not the surmise, and slightIs all that any mortal knows thereof), Thou wert to me that earnest of day’s light,When, like the back of a gold-mailèd saurian Heaving its slow length from Nilotic slime,The first long gleaming fissure runs Aurorian Athwart the yet dun firmament of prime.Stretched on the margin of the cruel sea Whence they had rescued me, With faint and painful pulses was I lying; Not yet discerning wellIf I had ‘scaped, or were an icicle, Whose thawing is its dying.Like one who sweats before a despot’s gate,Summoned by some presaging scroll of fate,And knows not whether kiss or dagger wait;And all so sickened is his countenance,The courtiers buzz, “Lo, doomed!” and look at him askance: — At Fate’s dread portal then Even so stood I, I ken,Even so stood I, between a joy and fear,And said to mine own heart, “Now if the end be here!”

They say, Earth’s beauty seems completest To them that on their death-beds rest; Gentle lady! she smiles sweetest Just ere she clasp us to her breast.And I, — now my Earth’s countenance grew bright,Did she but smile me towards that nuptial-night?But whileas on such dubious bed I lay, One unforgotten day, As a sick child waking sees Wide-eyed daisies Gazing on it from its hand, Slipped there for its dear amazes; So between thy father’s knees I saw thee stand, And through my hazesOf pain and fear thine eyes’ young wonder shone.Then, as flies scatter from a carrion, Or rooks in spreading gyres like broken smoke Wheel, when some sound their quietude has broke,Fled, at thy countenance, all that doubting spawn: The heart which I had questioned spoke,A cry impetuous from its depths was drawn, — “I take the omen of this face of dawn!”And with the omen to my heart cam’st thou. Even with a spray of tearsThat one light draft was fixed there for the years.

And now? — The hours I tread ooze memories of thee, Sweet! Beneath my casual feet. With rainfall as the lea, The day is drenched with thee; In little exquisite surprisesBubbling deliciousness of thee arises From sudden places, Under the common tracesOf my most lethargied and customed paces.

As an Arab journeyeth Through a sand of Ayaman, Lean Thirst, lolling its cracked tongue, Lagging by his side along; And a rusty-wingèd Death Grating its low flight before, Casting ribbèd shadows o’er The blank desert, blank and tan:He lifts by hap toward where the morning’s roots are His weary stare, — Sees, although they plashless mutes are, Set in a silver air Fountains of gelid shoots are, Making the daylight fairest fair; Sees the palm and tamarindTangle the tresses of a phantom wind; — A sight like innocence when one has sinned!A green and maiden freshness smiling there, While with unblinking glareThe tawny-hided desert crouches watching her.

’Tis a vision: Yet the greeneries Elysian He has known in tracts afar; Thus the enamouring fountains flow, Those the very palms that grow,By rare-gummed Sava, or Herbalimar. —

Such a watered dream has tarried Trembling on my desert arid; Even so Its lovely gleamings Seemings show Of things not seemings; And I gaze, Knowing that, beyond my ways, Verily All these are, for these are she. Eve no gentlier lays her cooling cheek On the burning brow of the sick earth, Sick with death, and sick with birth, Aeon to aeon, in secular fever twirled, Than thy shadow soothes this weak And distempered being of mine.In all I work, my hand includeth thine; Thou rushest down in every streamWhose passion frets my spirit’s deepening gorge;Unhood’st mine eyas-heart, and fliest my dream; Thou swing’st the hammers of my forge;As the innocent moon, that nothing does but shine,Moves all the labouring surges of the world. Pierce where thou wilt the springing thought in me,And there thy pictured countenance lies enfurled, As in the cut fern lies the imaged tree. This poor song that sings of thee, This fragile song, is but a curled Shell outgathered from thy sea, And murmurous still of its nativity. Princess of Smiles!Sorceress of most unlawful-lawful wiles! Cunning pit for gazers’ senses, Overstrewn with innocences! Purities gleam white like statues In the fair lakes of thine eyes, And I watch the sparkles that use There to rise, Knowing these Are bubbles from the calyces Of the lovely thoughts that breathePaving, like water-flowers, thy spirit’s floor beneath.

O thou most dear!Who art thy sex’s complex harmony God-set more facilely; To thee may love draw near Without one blame or fear,Unchidden save by his humility:Thou Perseus’ Shield! wherein I view secureThe mirrored Woman’s fateful-fair allure!Whom Heaven still leaves a twofold dignity,As girlhood gentle, and as boyhood free;With whom no most diaphanous webs enwindThe barèd limbs of the rebukeless mind.Wild Dryad! all unconscious of thy tree, With which indissolublyThe tyrannous time shall one day make thee whole;Whose frank arms pass unfretted through its bole: Who wear’st thy femineityLight as entrailèd blossoms, that shalt findIt erelong silver shackles unto thee.Thou whose young sex is yet but in thy soul; — As hoarded in the vineHang the gold skins of undelirious wine,As air sleeps, till it toss its limbs in breeze: — In whom the mystery which lures and sunders, Grapples and thrusts apart; endears, estranges; — The dragon to its own Hesperides — Is gated under slow-revolving changes,Manifold doors of heavy-hingèd years. So once, ere Heaven’s eyes were filled with wonders To see Laughter rise from Tears, Lay in beauty not yet mighty, Conchèd in translucencies, The antenatal Aphrodite,Caved magically under magic seas;Caved dreamlessly beneath the dreamful seas.

“Whose sex is in thy soul!” What think we of thy soul? Which has no parts, and cannot grow, Unfurled not from an embryo;Born of full stature, lineal to control; And yet a pigmy’s yoke must undergo.Yet must keep pace and tarry, patient, kind,With its unwilling scholar, the dull, tardy mind;