17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

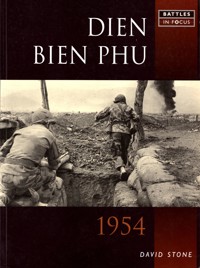

The French strategy of seeking to establish a fortified base across the Viet Minh's route to and from Laos provoked an awesome struggle that lasted from November 1953 to May 1954. During this time Dien Bien Phu, surrounded by 2000 ft hills and thus difficult to re-supply by air as the French had intended, became the scene of fearful contests between the locally savvy men of General Giap and the hapless French forces who, losing one strongpoint after another, were finally trapped in Dien Bien Phu garrison. The French lost the cream of their strategic reserve in the region and, within months, were agreeing to the independence of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. David Stone, a British Army officer of the post World War II era, leads the reader through the complex nature of this significant action.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 291

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

BATTLES IN FOCUS

DIEN BIEN PHU

Dien Bien Phu Valley, viewed from the high ground in early 1954.

BATTLES IN FOCUS

DIEN BIEN PHU

DAVID STONE

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

Introduction

Preface

1 THE CONFLICT IN FRENCH INDOCHINA

2 THE OPERATIONAL AND STRATEGIC DEBATE

3 OPENING MOVES

4 FRENCH ORGANISATION AND DEPLOYMENT

5 COMBAT CAPABILITY OF THE FRENCH UNION FORCES

6 COMBAT CAPABILITY OF THE COMMUNIST FORCES

7 BATTLE IS JOINED

8 CLOSE COMBAT

9 SHAPING THE FINAL BATTLE

10 INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS AND OTHER OPTIONS

11 PRELUDE TO DEFEAT

12 THE FINAL ONSLAUGHT

13 TRUTHS AND CONSEQUENCES

Bibliography

Notes

Index

AUTHOR’S NOTE

A number of accounts – both in French and in English – of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu are available today. Some of these deal with specific aspects of the battle in considerable detail, others with the battle in its entirety.1 Several mention the battle incidentally, within wider histories of the French army units involved – especially those of the French Foreign Legion or the French paratroops. Dien Bien Phu has also featured at various levels of detail in a number of general books on post-1945 military history. In addition, the many lessons of this battle have been analysed in the military staff training publications of several armies. Despite the existence of such a wealth of information, in the course of researching this book it became increasingly clear that there were in some cases factual discrepancies between these often diverse accounts – particularly where weapon and equipment holdings, force levels and organisations, and statistical summaries were concerned; but also between their differing descriptions of the actions of some individuals and units (especially below battalion-level).

Consequently, in this account of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, the subject has been approached in two ways. First, apart from a few essential exceptions, it concentrates on the French Union side of the conflict at battalion-level or above, and on the communist Viet Minh (or the ‘People’s Army of Vietnam’) forces generally at army and division-level. Second, this work attempts – through research and (in a very few cases) the application of a measure of professional military judgement – to rationalise and resolve the more important factual inconsistencies identified in some other accounts. Therefore, it is postulated that the resultant work is an accurate and authoritative account of all the key elements of the battle of Dien Bien Phu, together with a new perspective on many of the events and decisions that surrounded and influenced the course of this remarkable clash of arms – a defining moment in French and Vietnamese history, and unquestionably one of the most important battles of the Cold War era.

Finally, my particular thanks to Colonel (Retired) Nigel Flower, a long-term friend and a former colleague in the world of military intelligence. The final text of this work has benefited enormously from his positive suggestions and critical comments; but especially from the uniquely authoritative nature of these, consequent upon his special knowledge of Indo-China due to his assignment in former times as the UK Military Attaché in Vientiane, Laos, at the height of America’s war in Vietnam.

INTRODUCTION

In mid-1966, I was serving on a short attachment to the 11e Bataillon de Chasseurs Alpins (the French Army’s light infantry mountain warfare specialists). The battalion was stationed in the sleepy little town of Barcelonette in the Bas-Alpes. En route to Barcelonette I had spent a few days in the capital, where Paris was still showing signs of the earlier turmoil that had engulfed part of the French army. Only five years before, following what many viewed as the betrayal of the French army by General de Gaulle and the Paris government over its abandonment of Algeria, elements of the French Foreign Legion had mutinied, together with some other élite units and individuals. The Legion’s principal combat unit – the 1er Régiment Étranger de Parachutistes (1 REP) – had been disbanded, and the political reliability of a large element in the Legion and paratroop regiments remained uncertain in the eyes of the government. Elsewhere, strong undercurrents of political and national uncertainty persisted. Indeed, in 1966, in a mood of continuing paranoia in metropolitan France, several public buildings in Paris retained the rooftop machine-gun positions set up some five or six years earlier to counter an anticipated coup. But in Barcelonette such heady matters seemed far removed from the daily life of the Chasseurs Alpins in the picturesque French alpine region.

Then, one evening in the sous-officiers’ mess I encountered an adjudant-chef (senior warrant officer) whose three or four rows of medal ribbons, together with the paratrooper’s qualification wings on his chest and the green and gold ‘fourragère’ of the Médaille Militaire at his shoulder, indicated the extent of this man’s service. As the sun dropped below the mountains and the shadows lengthened outside, we talked. It transpired that he was completing the final months of his military service in the region in which he intended to settle as a civilian, and was happy to recount something of his military service to a ready listener from England. He told of his time in Indo-China and in Algeria. He spoke about a great battle that had taken place in a wide and fertile valley in north-west Tonkin close to the border with Laos; a major – but fatally flawed – military operation that had been designed finally to defeat the communist Viet Minh in northern Indo-China. He recalled the fate of many of his comrades for whom that battle had been their last; and he was still in no doubt that the responsibility for their deaths on that particular battlefield lay squarely at the door of the French politicians of the day. But then, as he observed, throughout history the French army had always been betrayed by the politicians in Paris, and occasionally by its generals as well; it was ever thus, and this was the burden that a French soldier must accept as an unavoidable consequence of his duty. Outside, the summer evening had long ago become night. He talked on. As he did so, the political tensions that I had noted in Paris came ever more into perspective, as I began to understand something of the impact of the wars in Indo-China, and Algeria upon the very soul of France and its army.

General Navarre (left), the French Union Forces Commander-in-Chief in Indo-China, in 1953.

When I finally bade my new-found acquaintance and raconteur goodnight the mess was almost deserted; while the small collection of empty Kronenbourg bottles on our table and the clock behind the bar bore testimony to the several hours that we had talked. As I walked to my accommodation, his tales of soldiering in Cochin-China, Annam and Tonkin – of that final cataclysmic struggle close to the Laotian border in 1954 in particular – remained vividly in my mind. By the time that I arrived at my quarters, I was sure that I would one day write an account of France’s war in Indo-China: specifically about the dramatic events, the heroism, the pathos and the enormous historical and military impact of the final great armed conflict of that war – the battle of Dien Bien Phu.

PREFACE

The battle that took place in the valley of Dien Bien Phu – literally the ‘administrative centre of the border region’ close to the Laotian border – to the west of Tonkin province was one of the most important clashes of arms of the twentieth century, and it could be argued that it was the most important battle involving a European power in the post-1945 period. For France, it was every bit as significant as the defeat that the imperial army of Napoleon III had suffered at the hands of Germany at Sedan almost a century before, in 1870: a military débâcle that in some respects echoed aspects of the conflict at Dien Bien Phu. At Sedan the French Army of Châlons was confined in a valley strong-point by the German forces, all the surrounding hills being occupied by the technologically superior German artillery which was able to observe and bring down an incessant and withering fire upon the immobile French forces. Even the immediate aftermath of Sedan, with a mass surrender of the French forces, inadequate arrangements for the prisoners taken, and their removal into the hinterland of their enemies resembled (albeit superficially) the events that followed Dien Bien Phu. Meanwhile, at the strategic and international level, Sedan signalled the end of the Napoléonic dynasty and the French Second Empire, and the birth of the German empire; just as Dien Bien Phu precipitated the end of France’s colonial empire, the rise and return to power of General de Gaulle, and the creation of the sovereign states of North and South Vietnam. This in turn led to a further twenty years of warfare in Indo-China, and eventually culminated in the defeat of yet another great power at the hands of the North Vietnamese communists – but this time the vanquished would be no lesser nation than the United States of America.

The huge importance of Dien Bien Phu for France and its army was almost incalculable. Quite apart from the many essentially military lessons learnt, from that single great battle in Tonkin flowed years of political turmoil in a country and nation still trying to come to terms with the ignominious defeat of 1940, with the subsequent years of German occupation, with the years of the Vichy régime, and with the eventual liberation by the Western Allies. Despite Marshall Aid,2 the French people were also still coping with the legacy of collateral damage and civilian casualties that liberation had inevitably inflicted upon much of northern France. But Dien Bien Phu was also the catalyst for change that further widened what was already an almost unbridgeable gap between the French government and a significant part of the regular French army: many of whose units and organisations had been fighting and dying on the front lines of France’s colonial wars since 1945.

One organisation in particular was changed forever by Dien Bien Phu: the French Foreign Legion, which had been fighting for France in North Africa, and in some of the most inhospitable, disease-ridden and far-flung French colonies and territories ever since 1831. At Dien Bien Phu the Legion amassed further glory, but it was also politicised by a conflict in Indo-China that had so clearly been mismanaged by an uncaring and inept government in Paris and an apathetic or openly hostile population in metropolitan France. For the élite regular units of a justifiably proud but (in the view of many professional officers and soldiers) now betrayed French army, the seeds of disillusion and unease sown during almost ten years battling the Viet Minh finally germinated at Dien Bien Phu. They then blossomed and burst forth during the subsequent conflict in French Algeria; culminating in mutiny, criminality and terrorism – with the consequent dishonour and punishment of numerous senior officers, junior officers and soldiers, and the disgrace of a number of justifiably once-proud units. For the French Foreign Legion, the final abandonment of Algeria in 1962 was both an annulment of the unwritten contract between the Legion and France, and the abrogation of the Legion’s very raison d’être.

Thus Dien Bien Phu and its aftermath exposed the nadir of French global military power in a long process of decline that had in reality begun more than one and a half centuries earlier, at the hands of the British and Prussians on the battlefield of Waterloo. For the French army, after Indo-China and Algeria nothing could ever be the same again, and for the Legion and the regular army alike these conflicts served to provide a new beginning, and allowed France, quite correctly, to develop its armed forces in a European and (albeit qualified) NATO context rather than as the imperialistic and colonising forces they had been for some three or four centuries. Although traumatic, the change has been good for the army, and its uniquely French approach to intervention overseas, co-operation, multi-nationalism, and the avoidance of the post-1990 political correctness3 that has increasingly be-devilled and weakened many other western European armies since the end of the Cold War, has ensured that France now has forces of which it can again be proud, and which are well up to dealing with modern military missions internally and externally in a troubled and unstable world. And Dien Bien Phu and its aftermath were, indirectly, major contributors to this process of change.

One potential consequence of Dien Bien Phu was particularly dramatic, for at one stage the battle might well have become the scene of the first use of atomic weapons by the United States since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in order to retrieve the otherwise hopeless French military situation. Had this attack been carried out, the escalation of the conflict beyond the region would have been virtually inevitable. In 1954 it was some five years since the Soviet Union had carried out its own first successful atomic explosion, and so the potential global implications of the US use of atomic weapons in Indo-China were all too obvious. Nevertheless, the US plan had been made, suitably small yield atomic weapons identified for the task, and presidential authority would probably have been forthcoming to strike the Viet Minh positions around the Dien Bien Phu valley with air-dropped atomic bombs. However, the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill refused to authorise the wholehearted military involvement of Great Britain in the Indo-China venture, and this was a non-negotiable pre-condition for US action that had been set by the US Congress, together with France being required to abandon its future claims to its Far East territories – a requirement to which Paris was in any case not prepared to accede. Consequently, neither atomic nor conventional bombing by the USAF were forthcoming to save the beleaguered garrison, and this contributed directly to the often difficult state of US-Anglo-French relations during the 1950s and 1960s. It also confirmed de Gaulle’s views and prejudices concerning the motives of his erstwhile Second World War allies, the position of France in NATO, and the urgent need for France to forgo its defence reliance on the United States and to develop its own independent strategic nuclear capability. Later, US intervention to foreclose the Anglo-French Suez operation in 1956 served to confirm and finally set the seal on de Gaulle’s view of the administration in Washington.

But if the impact of Dien Bien Phu for France was enormous, its wider international consequences were just as significant. The French defeat might indeed have ended the First Indo-China War 1945–54, but in practice it directly paved the way for the Second Indo-China War – the Vietnam War – and for the escalating US involvement in the region. At the same time, the military defeat of a major European power by what was viewed as a communist insurgent army confirmed the post-1945 vulnerability of the European powers, and the perception in many parts of the world that the day of their once-great empires was indeed past. Clearly, the red star of communism was in the ascendancy, and such perceptions fuelled the many existing and embryo communist and nationalist movements in the remaining European colonies in the Far East, Asia and Africa; and also bolstered the Soviet Union’s stranglehold on eastern Europe.

Thus the battle of Dien Bien Phu was indeed a defining moment in the history of warfare, that of the world in general and of the Cold War in particular.

1

THE CONFLICT IN FRENCH INDO-CHINA

The long, bitter struggle of the peoples of French Indo-China and (since 1954) of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, to shape their future has been extensively documented and much studied during the last half century. The war carried on by the communists against the French from 1946 to 1954 is often dealt with as a separate conflict from that which took place from 1954 against the South Vietnamese government and, soon thereafter, against the United States and its allies. However, a constant thread that ran from 1946 through to 1975 was the nature and motivation of the indigenous communist enemy and its political and military leaders. The movement began fairly inauspiciously with the founding of a Communist Party of Indo-China in 1930. From the 1940s, however, Ho Chi Minh and his military commander Vo Nguyen Giap transformed the old states and kingdoms of Indo-China – Cochin China, Tonkin, Annam (which together comprised Vietnam), Cambodia and Laos – from their 1893 status as part of the French colonial empire, into three communist-dominated sovereign states in 1975.

Throughout, this epic struggle was fought in the jungles, plains and mountains of Vietnam, and in the villages and cities of a country and region that became a perpetual battleground for three decades. Vietnam’s several mighty rivers, few all-weather road routes and countless jungle trails were the vital arteries along which flowed the armies and the matériel support that sustained them. Indeed, in terms of actual combat, a great deal of the Cold War that began in 1945 was in fact fought in South-East Asia: in French Indo-China, in the Republic of Korea, in Malaya and in the Republic of South Vietnam. And all of these conflicts were to varying degrees instrumental in shaping the fortunes and future strategic policies of Great Britain, France and the United States of America; the latter two countries in particular.

After 1945 Great Britain’s pragmatic policies for the transformation of its empire into the British Commonwealth pre-empted the usual arguments advanced by nationalist and liberation movements in many other European protectorates and colonies. Malaya was a prime example of this. Similarly, the view of communism that prevailed in Great Britain throughout the immediate post- Second World War years was much less ideological than that in the United States, where anti-communism was already rapidly assuming the status of a crusade.

But the French view of its overseas territories was somewhat different from that held by the British. Many of its possessions, in Indo-China especially, were relatively recent acquisitions – gained between 1862 and 1893 – and France derived many economic, trade and strategic benefits from them; just as many individual diplomatic, military and civil service careers benefited enormously from service in French Indo-China. Also, over a hundred-year period, much blood had been shed by the military forces of France (by the French Foreign Legion in particular) to secure its possessions in South-East Asia and North Africa. Meanwhile, in the liberated Paris of 1945 there was a popular if somewhat misplaced perception that France was once again a great power, and that the pre-1940 world would now be restored. Therefore, the French government was not minded to give up to any indigenous administration – communist or nationalist – the French territory in Indo-China that had been temporarily stolen by the Japanese in 1941. The decision that followed, to maintain total control of French Indo-China, eventually resulted in some 81,760 dead servicemen, including 11,620 legionnaires and 26,686 Indo-Chinese soldiers (mainly of the Vietnamese national army). It also indirectly paved the way for France’s subsequent defeat in Algeria, and the crisis that overtook the French army in 1961.

Apart from signalling the end of France as a great military and imperial power, the great significance of the events that took place in Indo-China from 1945 to 1954 was the way in which, imperceptibly at first and then with increasing inevitability, Vietnam changed from a French colonial battlefield to one on which the United States subsequently chose to make its stand against what the US commander in Korea in 1951, General Matthew B. Ridgway, called the ‘dead existence of a Godless world’ and the ‘misery and despair’ of communism. Arguably, the long-term scar that the US involvement left on America from 1975 was even greater than the crushing blow that France suffered in 1954. So how did this chain of events come about?

The military collapse at the hands of the Germans in 1940 provided a clear indication that France’s fortunes were truly in decline, and this fact was lost neither upon the Japanese, who proceeded to seize the French, British and Dutch territories in the Far East from 1941, nor upon the several nationalist organisations within those territories who assessed that the time for action had at last arrived. In French Indo-China one such organisation was the League for the Independence of Vietnam (‘Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi’, or ‘Viet Minh’), headed by the communist Ho Chi Minh. He was a native of Annam, the narrow strip of territory which ran almost the full length of the country from Cochin China in the south to Tonkin (and the Chinese border) in the north and was the main province of Vietnam, bordering both Cambodia and Laos along most of its length. To the east of Annam lay the coast, and beyond it was the South China Sea.

Under the guidance of its military leader, Vo Nguyen Giap – a man whose early life had shaped and borne significantly upon his rise within the Indo-Chinese communist movement,4 the Viet Minh carried out an effective guerrilla campaign against the French Vichy administration and Japanese occupation forces in the northern part of Indo-China, while co-ordinating its activities with other nationalist movements in the country. Indeed, the Viet Minh organisation was already expanding into main force, district guerrilla groups and village units, so that by early 1945 its development into a formidable armed force was progressing well.

In March 1945 the Japanese took savage military action against the small French garrisons (manned predominantly by legionnaires of the 5e Régiment Étranger d’Infanterie (5 REI) of the French Foreign Legion) that were scattered about the country. This act of treachery removed the token Vichy French administration headed by a number of pro-Japanese collaborators and enabled the Viet Minh to concentrate all its efforts against the Japanese. In turn, this produced increased military support from the United States, which now viewed the Viet Minh as the principal counter-Japanese force in the country. Apart from this, President Roosevelt had already made his position on Indo-China clear on 24 January 1944, when he indicated that France should vacate the country and permit the several peoples of Indo-China to decide their future by self-determination. Thus, when the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought about an unexpectedly abrupt end to the war in the region, the communists were sufficiently well armed and in control of events to establish the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, with its capital at Hanoi.

The new republic was declared on 2 September 1945. But in July that year the Allies had agreed at Potsdam that France would regain its Indo-Chinese possessions. France was in no position to do so in August 1945, and so in September British and nationalist Chinese forces occupied the south and north of the country respectively. The size of their task was such that, by October 1945, the British had found it necessary to re-arm some of the surrendered Japanese units in order for them to act as a paramilitary police force in the south of the country. The British force comprised the 26,000 men of Major General D. Gracey’s battle-hardened 20th Indian Division, plus air force and additional artillery support. But whereas the Chinese were content to deal with the Japanese without affecting the new régime in Hanoi, the British were firmly committed to return Indo-China to French control. Accordingly, on 5 October 1945 a French Expeditionary Corps, 21,500 strong and led by General Leclerc, entered Saigon and began the process of relieving the British forces, who handed over their temporary stewardship of southern Indo-China to the French on 9 October. In the months prior to and after the British withdrawal there was much political manoeuvring, and several violent confrontations between the communists, nationalists, French forces, French colonists, Gaullists, former Vichy supporters and forces and other disparate groups occurred. During this turbulent period various potentially workable compromises emerged, although none were acceptable to Paris. One such was Ho Chi Minh’s agreement to the stationing of 25,000 French and French-officered Vietnamese troops in the major urban areas (to be followed by a French withdrawal in five annual stages, with completion in 1952), in return for French recognition of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as a free state within both an Indo-Chinese Federation and the French Union.

The situation degenerated with each passing month, as two diametrically opposed philosophies and forces moved towards open conflict in early 1946. First of all there were the French, determined to retain control of French Indo-China at all costs. Second, there were the communists, inspired by a charismatic leader committed to establish an independent, communist-dominated Vietnamese republic. Although the motivation used by Ho Chi Minh was initially anti-colonialist, and then nationalist, there is little doubt that a communist state was always his ultimate goal throughout the war that was about to commence

A major amphibious landing had been carried out by the French at Haiphong in the Red River delta on 6 March 1946, and the always uneasy relationship between the French and the newly established government in Hanoi deteriorated rapidly, against a backdrop of small-scale armed clashes. The landing by large elements of the French Expeditionary Corps on 6 March had added thousands on troops to the 150,000 nationalist Chinese troops and Viet Minh forces already in the area of the Red River delta. For the local population the significance of this was dramatic, because the 1945 rice harvest had been very poor, and even before the arrival of these armies they were literally starving. Consequently, the Red River delta was particularly receptive to any action that might expel the French and Chinese occupiers.

Then, on 19 December, the Viet Minh struck French positions around Hanoi with artillery, mortar and small-arms fire, which severed the city’s electricity and water supplies. Shortly after this the guerrillas withdrew to their bases in the swamps and mountains of Tonkin and the area of the Chinese border. From there they prepared to conduct a classic revolutionary war in accordance with the principles expounded by Mao Tse-tung, whose own communist revolutionary war against the nationalist Chinese armies to the north was proceeding successfully.

Over the next three years the Viet Minh carried out numerous ambushes of French supply columns and attacks on isolated forts, as well as various acts of terrorism. Although the French forces (following the pattern of their colonial strategy of former times) were dispersed throughout the country, the main area of conflict was to the north of the country, in Tonkin. During those first years after the French return, the Foreign Legion bore the brunt of the attacks, and it continued to do so throughout France’s post-1945 involvement with Indo-China.

Significant numbers of men from many different countries had found themselves in the armed forces of the losing side in the recently ended Second World War, and – having lost everything in that great conflict or being unable to adjust to their much-changed personal circumstances in the turmoil of the post-1945 world – many of them had found a new home and raison d’être in the Legion. These legionnaires were now engaged very directly in France’s attempt to regain and maintain control of its territories in Indo-China. Although but one of hundreds of similar clashes, the particular nature of the Legion’s war in Indo-China was characterised by the defence of the outpost at Phu Tong Hoa by a company of the 3e Régiment Étranger d’Infanterie (3 REI), which took place on 25 July 1948. The small fort – with defences constructed in the main of sandbags, logs, wire, bunkers and entrenchments – lay astride the strategically important road that ran between Hanoi and the Chinese border. Soon after nightfall, the first salvo of mortar bombs exploded across the position. This presaged a sustained, heavy and accurate mortar bombardment which soon breached the defensive perimeter fence. The small company of legionnaires – less than 100 strong – was considerably outnumbered, and the Viet Minh attackers eventually overran more than half of the base. Despite this the legionnaires continued to fight on, both within and from the fort, until a relief force arrived three days later. By that stage, twenty-one legionnaires, including the two most senior officers, had been killed. Nevertheless, with a flair that has throughout its history typified the esprit de corps of the élite organisation to which they belonged, as the relief column reached the entrance to the outpost it found the forty surviving legionnaires of the garrison paraded in their best uniforms. As the reinforcements drove into the battered fort, these forty men who had just fought a desperate three-day battle to ensure that Phu Tong Hoa remained in French hands, snapped to attention and presented arms in accordance with time-honoured military tradition.

Ho Chi Minh (second left) and General Giap (right) at an operational planning meeting.

Such incidents were frequent and typical both of the nature of the Legion and of the war that it, together with the other French Union forces, was required to fight for France in Indo-China. Meanwhile, in an ill-disguised attempt to placate the nationalists in particular, but also the communists, while at the same time installing a ruler who would be entirely under French control, in April 1948 Paris had established the discredited former Emperor Bao Dai as the emperor of an independent Vietnam. Not surprisingly the Viet Minh leadership was unimpressed by this, and in February 1950, following a successful attack on the French outpost at Lao Cai on the Red River close to the Chinese border (an event which coincided with Mao’s victory in China and the prospect of significant quantities of Chinese aid5 for the Viet Minh in the future), Giap and Ho felt sufficiently confident to move their guerrilla campaign into the counter-offensive phase.6

Early in 1950 Giap had at his disposal two infantry divisions, plus heavy mortars and anti-aircraft guns; but by the end of that year he had increased the strength of his regular forces to three divisions, and (nominally) to six divisions by the end of 1951.7 Indeed, by 1954 the Viet Minh forces outnumbered the French Union forces. Throughout the war the French underestimated the Viet Minh capability, but two other important factors also affected French hopes and perceptions. First, the post-Roosevelt administration of President Truman, fuelled by McCarthyism and anti-communist sentiments in the United States – much reinforced by the North Korean invasion of South Korea in June 1950 – all indicated the possibility of American military support for the French cause. Second, the French government hoped that the National Assembly in Paris would authorise the deployment of conscripts to Indo-China, which would alleviate the chronic shortage of French troops and the consequent reliance upon regular units, the Legion and volunteers to serve there. But although America’s eventual post-1954 military involvement in Vietnam was massive, it never used its significant combat power to assist the French. Similarly, the use of conscripts to fight beyond metropolitan France was never sanctioned by the National Assembly; a decision much influenced by a disaster that befell the French forces in Tonkin in the early autumn of 1950.

In mid-September, just six weeks before the PLA launched its devastating offensive against the UN forces in Korea, Giap struck the French forces in north-east Tonkin. The Viet Minh operations began with a series of assaults against French positions on the Cao Bang–Lang Son ridge, where the full weight of their offensive fell upon the French position at Dong Khe on 16 September 1950.

Dong Khe was a forward outpost of the Legion, set high in the jungle-clad, mist-shrouded hills that lay along Tonkin’s border with China. The position was manned by some 260 men, comprising two companies of the 3 REI. The communist attack began with a heavy and accurate mortar barrage, followed during the next two days by further mortar bombardments interspersed with human wave attacks by more than 2,000 infantrymen. Time and again the attackers overran the perimeter defences and engaged in savage close combat with the legionnaires. Time and again they were forced to withdraw. But the final outcome of the battle was not in doubt, and at the end of the second day only a few of the surviving legionnaires had managed to escape from the shattered outpost. The significance of this battle extended well beyond the loss of a single outpost.

The fort at Dong Khe had previously been designated as the rendezvous for a French column that was already moving towards it from the small town of Cao Bang, about fifteen miles away. The column’s mission was to evacuate and escort the anti-communist civilian population of Cao Bang to safety, and in view of what transpired Giap must have already been aware of the particular significance of Dong Khe. Indeed, the outpost was critical to the safety of the French column, and the 1er Bataillon Étranger de Parachutistes (1 BEP) plus a large force of Moroccan troops – a total of some 5,000 men – tried unsuccessfully to recapture it. But this force was ambushed in the Coc Xa valley by as many as 30,000 Viet Minh guerrillas. Despite the gallantry and discipline of the legionnaires during a battle that lasted for more than two weeks, the force was gradually overwhelmed and, with the Moroccans’ morale on the verge of collapse, on 9 October the order came to break out of the valley. Only a handful of legionnaires and a number of terrified Moroccan soldiers managed to escape from the horrific few hours of fighting that ensued. The disaster was compounded shortly afterwards when the fleeing Moroccans reached the approaching column from Cao Bang, where their fear speedily infected the Moroccan troops of that force. At that moment the Viet Minh attacked the main column. The result was a massacre on a grand scale, one of the worst military defeats in French colonial history, which by 17 October left the Viet Minh in undisputed control of the border region and the principal supply routes into Tonkin from China. In the fighting about and between Dong Khe and Cao Bang the French lost about 7,000 men dead or as prisoners. The force had originally numbered about 10,000 in all. The recently formed 1 BEP was almost annihilated, and only about a dozen of its paratroopers survived. These men eventually reached the safety of the main French positions to the south, led by the battalion’s adjutant, Captain Pierre Jeanpierre.8