8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

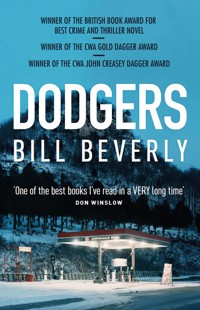

Winner of the British Book Award for Best Crime and Thriller Novel 2017 Winner of the CWA Goldsboro Gold Dagger 2016 Winner of the CWA John Creasey New Blood Dagger 2016 Winner of the LA Times Book Prize 2017 Shortlisted for the British Book Award for Overall Book of the Year 2017 Shortlisted for the Edgar Award for Best First Novel 2017 Finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Fiction 2017 Shortlisted for the Barry Award for Best First Novel 2017 East, a low-level lookout for a Los Angeles drug organisation, loses his watch house in a police raid. So his boss recruits him for a very different job: a road trip - straight down the middle of white, rural America - to assassinate a judge in Wisconsin. Having no choice, East and a crew of untested boys leave the only home they've ever known in a nondescript blue van, with a roll of cash, a map and a gun they shouldn't have. By way of The Wire and in the spirit of Scott Smith's A Simple Plan and Richard Price's Clockers, Dodgers is itself something entirely original: a gripping literary crime novel with a compact cast whose intimate story opens up to become a reflection on the nature of belonging and reinvention. 'One of the greatest literary crime novels you will read in your lifetime'Donald Ray Pollock, author ofKnockemstiffand The Devil All the Time 'Provocative, gripping, and timely, Dodgers is a riveting read that leaves a lasting impression' American Bookseller's Association 'A road movie, a coming-of-age tale, a crime novel of gritty realism and a hugely impressive debut.'Irish Times

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

When East, a low-level lookout for a Los Angeles drug organisation, loses his watch house in a police raid, his boss recruits him for a very different job: a road trip – straight down the middle of white, rural America – to assassinate a judge in Wisconsin.

Having no choice, East and a crew of untested boys – including his trigger-happy younger brother, Ty – leave the only home they’ve ever known in a nondescript blue van, with a roll of cash, a map and a gun they shouldn’t have.

Along the way, the country surprises East. The blood on his hands isn’t the blood he expects. And he reaches places where only he can decide which way to go – or which person to become.

By way of The Wire and in the spirit of Scott Smith’s A Simple Plan and Richard Price’s Clockers, Dodgers is itself something entirely original: a gripping literary crime novel with a compact cast whose intimate story opens up to become a reflection on the nature of belonging and reinvention.

About the Author

Bill Beverly was born and grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He studied literature and writing at Oberlin College, including time in London studying theatre and the Industrial Revolution. He then studied fiction and pursued a Ph.D. in American literature at the University of Florida. His research on criminal fugitives and the stories surrounding them became the book On the Lam: Narratives of Flight in J. Edgar Hoover’s America. He now teaches American literature and writing at Trinity University in Washington D.C. and lives with his wife, the poet and writer Deborah Ager, and their daughter Olive, in Hyattsville, Maryland. He collects beer cans. Dodgers is his debut novel.

Praise for DODGERS

‘Dark, edgy and riveting and, for all that, deeply, humanly serious, Dodgers is white knuckles for the mind. I love this book and will closely follow Bill Beverly forever hereafter’ – Robert Olen Butler, Pulitzer Prize winning author of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain

‘Not only is the fast-paced and masterfully plotted Dodgers one of the greatest literary crime novels you will read in your lifetime, Bill Beverley has also created, in the teenage boy, East, one of the most unforgettable and heartbreaking characters ever encountered in American fiction’ – Donald Ray Pollock, author of Knockemstiff & The Devil All the Time

‘Propulsive, brutally honest and yet unexpectedly tender, Dodgers is one of the best debuts I’ve read. I was absolutely gripped by the voice, the world of East and his brother, and surprised at nearly every turn. I audibly gasped at the end’ – Attica Locke, author of Black Water Rising and Pleasantville

‘Reading Dodgers is like having the veil lifted from your eyes: the world is more vivid, more intense, more exquisite, and more terrifying than you ever knew. Bill Beverly is a conjurer, a poet of the dark arts, and his novel is a spell: when he sends his young drug-world protagonist on a deadly errand in the alien landscape east of LA – that fat swath of America known to him only by its names and its shapes on maps – it is you who makes the journey, who is the stranger in a strange land, a watcher who now feels the eyes of others wherever you go, and who must pay the devastating tolls of crossing boundaries. Hypnotic, breath-taking, bruising, beautiful, important, true – choose your adjectives, this is a great novel – Tim Johnston, author of Descent

‘In Dodgers, Bill Beverly delivers with honesty and empathy as he takes us into the hope-killing shadow of LA’s street-level drug kingdom. His prose are a perfect match for young East’s life-altering journey; spare, clear-eyed and with the cutting edge of flint. Beverly leads us into the heart of a young man molded by circumstance and, much as Richard Price’s The Whites, gives a view that will change the way you look at the world’ – Susan Crandall, national bestselling author of Whistling Past the Graveyard

‘The sentences will snare you, and the story keeps you hooked – a thrilling cross-country journey that takes on the poetry and resonance of myth’ – Adam Sternbergh, author of Shovel Ready and Near Enemy

‘Bill Beverly’s wild and auspicious debut takes off from page one and never lets up. Dodgers, a kind of modernized and urban take on Theodore Weesner’s The Car Thief, is lightning-quick and world-wise, full of pitch-perfect dialogue and criminal misadventure. Most importantly, it’s a lot of fun’ – Tom Cooper, author of The Marauders

‘Dodgers transcends genres. Its main character East, is part Kerouac’s Sal Paradise, Part Wrights’ Bigger Thomas, and even part Salinger’s Holden Caulfield. The hero’s journey is an American story’ – Ernesto Quinonez, author of Bodega Dreams

‘Dodgers is a wickedly good amalgamation of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Clockers that stands firmly on its own as a remarkable debut. A harrowing road trip into the heart of America that will shock you, move you, and leave you marveling at its desolate poetry. A real accomplishment: a book that makes you see the familiar through new eyes. It will stick with me for a long, long time’ – Richard Lange, author of Angel Baby and This Wicked World

‘Bill Beverly’s gritty and propulsive debut novel, Dodgers, is more than a riveting read; it is a stunning literary achievement. Our hero, East, a fifteen-year old hit man, drives across America on a deadly mission, from the mean streets of LA to the heart of the country. East is a character as memorable and as haunting as any I’ve met in contemporary fiction. And he’s not alone in that van, but there is room for one more. So hop in, but strap on your seatbelt and hold on to your hat. The road’s a little bumpy – and more than a little terrifying – up ahead’ – John Dufresne, author of No Regrets, Coyote

‘A terrific novel, urgent, thrilling, and dangerous from start to finish. In East, Mr Beverly has created a character who stays in the mind after the book is finished, an Odysseus straight out of Compton. His venture into the unknown lands of the American Midwest has a classic, mythic shape and scope. And the writing throughout is lovely, economical and exact. You could read this for the sentences alone’ – Kevin Canty, author of Into the Great Wide Open

‘I knew before I’d gone very far into Bill Beverly’s superb first novel that I was about to lose some sleep, since putting it down seemed to be beyond me. To say it’s a page-turner doesn’t do it justice, though it certainly is. It’s also much more. His characters are vivid and real, and yes, sometimes they’ll break your heart. The world they inhabit--no matter where they may be at a given moment--all but leaps off the page. It’s a winner. So is its author’ – Steve Yarbrough, author of The Realm of Last Chances and Safe from the Neighbors

‘From the moment we encounter East, a mostly silent kid who ‘didn’t look like much,’ we are initiated into his gaze on the malfunctioning world, a kind of concentrated, exquisite hypervigilance that is both his burden and his gift. It is this quality of attention that makes Dodgers such an intense read - inescapable, inevitable, impossible to set aside. We can no more turn off East’s vision - and the sense of urgency that comes with it - than he himself can, and we are along for the ride. The truth-telling and pared-down purity of voice here are reminiscent of Denis Johnson, as if this novel were not written but channelled. This is a beautiful, extraordinary book’ – Wendy Brenner, author of Large Animals in Everyday Life and Phone Calls from the Dead

This book is for Olive, who gave me a new life

And giving a last look at the aspect of the house, and at

a few small children who were playing at the door, I sallied

forth… my course lay through thick and heavy woods

and back lands to town, where my brother lived.

James W. C. Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith (1849)

Every cheap hood strikes a bargain with the world.

The Clash, ‘Death or Glory’

Contents

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part II

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part III

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Acknowledgments

Copyright

I

THE BOXES

1

THE BOXESWASALL the boys knew; it was the only place.

In the street one car moved, between the whole vehicles and skeletal remains, creeping over paper and glass.

The boys stood guard. They watched light fill between the black houses separated only barely, like a row of loose teeth. Half the night they had been there: Fin taught that you did not make a boy stand yard all night. Half was right. To change in the middle kept them on their toes, Fin said. It kept them awake. It made them like men.

The door of the house opened, and two U’s stumbled out, shocked by the sun, ogling it like an old girl they hadn’t seen lately. Some men left the house like this, better once they’d been in. Others walked easy going in but barely crawled their way out. The two ignored the boys at their watch. At the end of the walk, they descended the five steps to the sidewalk, steadied themselves on the low stone wall. One man slapped the other’s palm loudly, the old way.

Again the door opened. A skeletal face, lip-curled, staring, hair rubbed away from his head. Sidney. He and Johnny ran the house, kept business, saw the goods in and the money out with teenage runners every half hour. Sidney looked this way and that like a rat sampling the air, then slid something onto the step. Cans of Coke and energy drink, cold in a cardboard box. One of the boys went and fetched the box around; each boy took a can or two. They popped the tops and stood drinking fizz in the shadows.

The morning was still chilly with a hint of damp. Light began to spill between the houses, keying the street in pink. Footsteps approached from the right, a worker man leaving for work, jacket and yellow tie, gold ear studs. The boys stared down over him; he didn’t look up. These men, the black men who wore ties with metal pins, who made wages but somehow had not left The Boxes: you didn’t talk to them. You didn’t let them up in the house. These men, if they came up in the house and were lost, someone needed them, someone would come looking. So you did not admit them. That was another thing Fin taught.

Televisions came on and planes flashed like blades in the sky. Somewhere behind them a lawn sprinkler hissed – fist, fist, fist – not loud but nothing else jamming up its frequency. A few U’s came in together at seven and one more at about eight, crestfallen: he had that grievous look of a man who’d bought for a week but used up in a night. At ten the boys who had come on at two left. The lead outside boy, East, shared some money out to them as they went. It was Monday, payday, outside the house.

The new boys at ten were Dap, Antonio, Marsonius called Sony, and Needle. Needle took the north end, watching the street, and Dap the south. Antonio and Sony stayed at the house with East, whose twelve hours’ work ended at noon. Antonio and Sony were good daytime boys. The night boys, you needed boys who knew how to stay quiet and stay awake. The day boys just needed to know how to look quiet.

East looked quiet and kept quiet. He didn’t look hard. He didn’t look like much. He blended in, didn’t talk much, was the skinniest of the bunch. There wasn’t much to him. But he watched and listened to people. What he heard he remembered.

The boys had their talk – names they gave themselves, ways they built up. East did not play along with them. They thought East hard and sour. Unlike the boys, who came from homes with mothers or from dens of other boys, East slept alone, somewhere no one knew. He had been at the old house before them, and he had seen things they had never seen. He had seen a reverend shot on the walk, a woman jump off a roof. He had seen a helicopter crash into trees and a man, out of his mind, pick up a downed power cable and stand, illuminated. He had seen the police come down, and still the house continued on.

He was no fun, and they respected him, for though he was young, he had none in him of what they most hated in themselves: their childishness. He had never been a child. Not that they had seen.

A fire truck boomed past sometime after ten, sirens and motors and the crushing of the tires on the asphalt. The firemen glared out at the boys.

They were lost. Streets in The Boxes were a maze: one piece didn’t match up straight with the next. So you might look for a house on the next block, but the next one didn’t follow up from this one. The street signs were twisted every which way or were gone.

The fire truck returned a minute later, going the other way. The boys waved. They were all in their teens, growing up, but everyone liked a fire truck.

‘Over there,’ said Sony.

‘What?’ said Antonio.

‘Somebody house on fire,’ said Sony.

The smoke rose, soft and gray, against the bright sky. ‘Probably a kitchen fire,’ East said. No ruckus, nobody burning up. You could hear the wailing a mile away when someone was burning up, even in The Boxes. But more fire engines kept rumbling in. The boys heard them on the other streets.

A helicopter wagged its tail overhead.

By eleven it was getting hot, and two men crashed out of the house. One was fine and left, but one lay down in the grass.

‘Go on,’ Sony told him. ‘Get out of here.’

‘You shut the fuck up, young fellow,’ said the man, maybe forty years of age. He had a bee-stung nose, and under his half-open shirt East saw a bandage where the man had hurt himself.

‘You go on,’ said East. ‘Go on in the backyard if you got to lie down. Or go home. Not here.’

‘This my house, son,’ said the man, fighting to recline.

East nodded, grim and patient. ‘This my lawn,’ he said. ‘Rules are rules. Go back in if you can’t walk. Don’t be here.’

The man put his hand in his pocket, but East could see he didn’t have anything in there, even keys.

‘Man, you okay,’ East said. ‘Nobody messing with you. Just can’t have people lying round the yard.’ He prodded the man’s leg lightly. ‘You understand.’

‘I own this house,’ said the man.

Whether this was true, East did not know. ‘Go on,’ he said. ‘Sleep in back if you want.’

The man got up and went into the backyard. After a few minutes Sony checked on him and found him asleep, trembling, fighting something inside.

The fire’s smoke seemed to thin, then came thicker. Trucks and pumps droned, and down the street some neighbor children were bouncing a ball off the front wall. East recognized two kids – from a neat house with green awnings, where sometimes a white Ford parked. These kids kept away. Someone told them, or perhaps they just knew. For the last two days there had been a third girl playing too, bigger. She could have grabbed every ball if she’d wanted, but she played nice.

East made himself stop watching them and studied the chopper instead where it dangled, breaking up the sky.

When he glanced back, the game had stopped and the girl was staring. Directly at him, and then she started to come. He glared at her, but she kept advancing, slowly, the two neighbor kids sticking behind her.

She was maybe ten.

East pushed off. Casually he loped down the yard. Sony was already bristling: ‘Get back up the street, girl.’ East flattened his hand over his lowest rib: Easy.

The girl was stout, round-faced, dark-skinned, in a clean white shirt. She addressed them brightly: ‘This a crack house, ain’t it?’

That’s what Fin said: everyone still thought it was all crack. ‘Naw.’ East glanced at Sony. ‘Where you come from?’

‘I’m from Jackson, Mississippi. I go to New Hope Christian School in Jackson.’ She nodded back at the neighborhood kids. ‘Them’s my cousins. My aunt’s getting married in Santa Monica tomorrow.’

‘Girl, we don’t give a fuck,’ said Antonio, up in the yard. ‘Listen to these little gangsters,’ the girl sang. ‘Y’all even go to school?’

Probably from a good neighborhood, this girl. Probably had a mother who told her, Keep away from them LA ghetto boys, so what was the first thing she did?

East clipped his voice short. ‘You don’t want to be over here. You want to get on and play.’

‘You don’t know nothing about what I want,’ boasted the girl. She waved at Antonio. ‘And this little boy here who looks like fourth grade. What are you? Nine?’

‘Damn,’ Sony cheered her, chuckling.

Somewhere fire engines were gunning, moving again; East stepped back and listened. A woman and a daughter walked by arguing about candy. And the helicopter still chopping. It tensed East up. There were too many parts moving.

‘Girl, back off,’ he said. ‘I don’t need you mixed up.’

‘You’re mixed up,’ said the girl. She put one hand on the wall, immovable like little black girls got. A fighter.

‘This kid,’ East snorted. The last thing you wanted by the house was a bunch of kids. Women had sense. Men could be warned. But kids, they were gonna see for themselves.

A screech careened up the flat face of the street, hard to say from where. Tires. East’s talkie phone crackled on his hip. He scooped it up. It was Needle at the north lookout. But all East heard was panting, like someone running or being held down. ‘What is it?’ East said. ‘What is it?’ Nothing.

He scanned, backpedaling up the lawn.

Something was coming. Both directions, echoing, like a train. He radioed inside. ‘Sidney. Something coming.’ The helicopter was dipping above them now.

Sidney, cranky: ‘Man, what?’

‘Get out the back now,’ East said. ‘Go.’

‘Now?’ said Sidney incredulously.

‘Now.’ He turned. ‘You boys, get,’ he ordered Antonio and Sony. Knowing they knew how and where to go. Having taught them what to do. Everyone on East’s crew knew the yards around, the ways you could go; he made sure of it.

The roar climbed the street – five cars flying from each end, big white cruisers. They raised the dust as they screeched in aslant. East thumbed his phone back on.

‘Get out. Get out.’ Already he was sliding away from the house. His house. Red Coke can on its side in the grass, foaming. No time to pick it up.

Sidney did not radio back.

How had this gotten past Dap and Needle? Without a warning? Unaccountable. Angry, he slipped down the wall to the sidewalk. The smell of engine heat and wasted tire rubber hung heavy. The other boys were gone. Now it was just him and the girl.

‘I told you,’ he hissed. ‘Go on!’

Stubborn thing. She ignored him. Staring behind her at the herd of white cars and polished helmets and deep black ribbed vests: now, this was something to see.

Four of the cops got low, split up, and gang-rushed the porch. Upstairs a window was thrown open, and in it, like a fish in rusty water, an ancient, ravaged face swam up. It looked over the scene for a moment, then poked out a gun barrel. East whirled then. The girl.

‘Damn!’ he yelled. ‘Get out of here!’

The girl, of course, did not budge. The pop-pop began.

East hit the sidewalk, crouched below the low wall. Beneath the guns’ sound the cops barked happily, ducking behind their cars like on TV. Everyone took shelter except the copter and the street dogs, howling merrily, and the Jackson girl.

East fit behind a parked Buick, rusted red. His breath fled him, speedy and light. The car was heat-blistered, and he tried not to touch it. Behind him the air was clouding over with bullets and fragments of the front of the house. Cop radios blared and spat inside the cruisers. The gun upstairs cracked past them, around them, off the street, into the cars, perforating a windshield, making a tire sigh.

The girl, stranded, peered up at the house. Then she faced where East had run, seeing he’d been right. She caught his eye. With a hand he began a wave: Come with me. Come here.

Then the bullet ripped into her.

East knew how shot people were, stumbling or crawling or trying to outrace the bullet, what it was doing inside them. The girl didn’t. She flinched: East watched. Then she put her hands out, and gently she lay down. Uncertainly she looked at the sky, and for a moment he disbelieved it all – it couldn’t have hit her, the bullet. This girl was just crazy. Just as unreal as the fire.

Then the blood began inside the white cotton shirt. Her eyes wandered and locked on him. Dying fast and gently.

The talkie whistled again.

‘God damn you, boy,’ Sidney panted.

The police in the back saw their chance, and three of them aimed. The gun in the window fell, rattling down the roof. Just then the four cops on the porch kicked in the door.

‘You supposed to warn us,’ crackled Sidney. ‘You supposed to do your job.’

‘I gave you all I got,’ East said.

Sidney didn’t answer. East heard him wheezing.

He got off the phone. He knew how to go. One last look – windows blown out, cops scaling the lawn, one U stumbling out as if he were on fire. His house. And the Jackson girl on the sidewalk, her blood on the crawl, a long finger pointing toward the gutter, finding its way. A cop bent over her, but she was staring after East. She watched East all the way down the street till he found a corner and turned away.

2

THEMEET-UPWASA mile away in an underground garage beneath a tint-and-detail shop with no name. The garage had been shut down years ago – something about codes, earthquakes – but you could still get a car in, through a busted wall in the lot below some apartments next door. Nothing kept people away from a parking space for long.

East took the stairs with his shirt held over his nose. The air reeked of piss and powdered concrete. Three levels down he popped the door and let it close behind him before he breathed again. A few electric lights still hung whole and working from a forgotten power line. Something moved along a crack in the ceiling, surviving.

East wondered who’d be there. Fin had hundreds of people in The Boxes and beyond. After things went wrong, a meet like this might be strictly chain-of-command. Or it might be with somebody you didn’t want to meet. Either way, you had to show up.

Down at the end he saw Sidney’s car: a Magnum wagon, all black matte. Johnny reclined against it, doing his stretches. He squared his arms behind his head and curled his torso this way and that, muscles bolting up and receding. Then he bent and swept his elbows near the ground.

Sidney stood away in the darkness with his little snub gun eyeing East’s head.

‘Failing, third-rate, sorry motherfucker.’

East went still. They said that down here people got killed sometimes, bodies dropped down the airshaft into the dark where nothing could smell them. He looked flatly past the gun.

Sidney was hot. ‘I don’t like losing houses. Fin don’t like losing houses.’

‘I ain’t found out yet what happened,’ East said simply.

‘Your boys ain’t shit. Who was it?’

‘Dap. Needle.’

‘Someone’s stupid. Someone didn’t care.’

East objected, ‘They know their jobs. That was my house I had for two years.’

‘I had the house, boy,’ Sidney spat. ‘You had the yard.’

East nodded. ‘I was there a long time.’

‘Best house we had in The Boxes. Fin loves your skinny ass – you tell him it’s gone.’

It was not the first gun East had talked down. You did not fidget. You showed them that you were not scared. You waited.

Just then, Sidney’s phone crackled. He uncocked his gun and stuck it away. Behind him, Johnny wagged his head and got off the car. Johnny was a strange go-along, dark black and slow-moving where Sidney was half Chinese, wound up all the time. Johnny was funny. He could be nice; he handled problems inside the house, kept the U’s from fighting with each other. But you did not want to raise his temperature.

‘Sidney don’t relish the running,’ Johnny laughed. ‘In case you wasn’t clear about that.’

East breathed again. ‘Did everyone get out?’

‘Barely. They got some U’s. No money and no goods.’

‘Who was shooting out?’

‘I don’t know, man. Some old fool, shotgun in his pants. We was grabbing and getting. I guess you could say he was too.’

Sidney put his phone away. He turned, fuming. ‘Someone did get shot.’

‘I know it,’ said East. ‘Little girl.’ He could see the Jackson girl, the roundness of her face, like a plum, a little pink something tied in her hair.

‘In the news it ain’t gonna be no little girl,’ said Johnny. ‘Gonna be a very big girl. It’s a little girl when your ass gets shot.’

This had been a bad time. Fin’s man Marcus had been picked up three months ago. Marcus kept bank, never carried, never drove fast or packed a gun, quiet. He had a bad baby arm with seven fingers on his hand. He knew in his head where everything came from and where it went, where it was – no books, nothing to hide. Twenty-two years old, skilled, smart: Fin liked that. But they had him now, no bail. No bail meant the PD could just keep asking him questions till they ran out of questions. Since then, everything was getting tight. One lookout picked up just loitering – they kept him in for three days. Runners getting scooped off the street, just kids, police rounding them up in a boil of cars and lights, breaking them down.

Some judge wanted a war, so everything had gotten hard.

They rode the black wagon south unhappily. Sidney coughed wetly, like the running had made him lung-sick. He wiped his gargoyle face. ‘Don’t look at the street signs,’ he snapped.

‘Man, who cares? I know what street this is,’ said Johnny. Something went pumma, pumma, pum in the speaker box, and the AC prickled hard on East’s face. He closed his eyes, like Sidney said, and didn’t look out at the street.

Losing the house – it was going to be on him. He owned the daytime boys; he owned their failure. He’d run the yard for two years, and he’d taught the lookouts, and until today everyone said he’d done it well. His boys knew their jobs; they came on time, they didn’t fight, didn’t make noise. He could not see where it’d gone wrong. That girl – he shouldn’t have talked to her for so long. Maybe she would have wandered off. He could have let Antonio muscle her a bit. She wound up dead anyhow.

What could he do? That many cops come to take a house, they’re gonna take it.

A pair of dogs went wild as the car slowed, but East didn’t open his eyes. Some of the neighbors’ dogs likely were Fin’s. Most people would keep a good dog if you gave them the food for it. And the cops looked where the dogs were. You didn’t keep dogs where you stayed.

‘Don’t look at the house numbers.’

‘Man, how I’m not gonna see what house it is?’ countered Johnny.

They parked down the street and walked. A little girl on a hollow tricycle scraped the sidewalk with her plastic wheels. The day had turned hot and windy. When Sidney said, ‘Hyep,’ they all turned and mounted two steps up toward a flat yellow house.

FORSALE, said a sign. Someone had blacked out the real estate agent’s name.

Answering the door was a short, stark-faced woman East had seen once before somewhere. On her hair she wore a jeweled black net. Her mouth was thin and colorless, slashed in. She showed them in, then retreated, into a kitchen where something bubbled but gave no smell.

The room was empty, bare, brown wood floors. The drawn blinds muted the daylight into purples. A lonely nail on the walls here and there told of people who’d lived here once. There were two guns there too, Circo and Shawn. East had seen them before. It was never good, seeing them.

‘Everyone get out your house when it happen?’ asked Shawn. He was a tall kid, like Johnny.

‘Little bitch didn’t even give us a heads-up,’ flared Sidney.

East ignored it. It wasn’t Sidney he had to answer to now. He wondered how much about it everyone knew.

Shawn wiped out the inside of his cheek with a finger and bit his lips unpleasantly.

‘Gonna need me in Westwood tomorrow?’

‘Depends. See what the day brings,’ said Sidney. ‘Miracles happen.’

Shawn laughed once, more of a cough. He patted the bulk in the pocket of his jeans approvingly.

A security system beeped, and down the hall a door opened – just a click and a whisper of air. The woman exited the kitchen softly, on bare feet, and turned down the hall. She slipped inside the cracked door and shut it. A moment later it beeped open again. East watched the woman. She had a spell about her, like her time in this world was spent arranging things in another.

She pointed at East, Sidney, and Johnny. ‘You can come,’ she said calmly.

East had been in rooms like this before, where guns had talked vaguely amongst themselves. Until today, the day he’d lost the house, he’d found it exciting. Today he was glad to be summoned away. He caught a scent trailing from her body as he followed, and inhaled. Usually if he got this close to a woman, it was a U, heading in or out. Or one working the sidewalk, or stained from the fry grill. This woman was perfumed with something strange that didn’t come out of a bottle. He held his breath.

The net in her hair glistened: tiny black pearls.

The system beeped again as she unsealed the door.

Fin’s room: unlit except for two candles. He sat in a corner, barefoot and cross-legged atop a dark ottoman, his head bowed as if in prayer, a candle’s gleam splitting his scalp in two. He was a big man, loose and large, and his shoulders loomed under his shirt.

This room had a dark, soft carpet. A second ottoman sat empty in the center of the room.

Fin raised his head. ‘Take off your shoes.’

East bent and scuffled with his laces. In the doorway behind them appeared Circo, a boy of nineteen with a cop’s belt, gun on one side and nightstick on the other. He stuck his nose in, looked around, and left. Good. The door beeped as the woman pulled it shut behind her.

Johnny took a cigarette out.

‘Don’t smoke in here, man,’ Fin said.

Johnny fumbled it back into the pack. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘House is for sale.’ Fin wiped the back of his head. ‘Purchase it if you like. Then you can do whatever you want.’

The three boys arranged their shoes by the door.

Dust curled and floated above the candles. Fin sat waiting, like a schoolteacher. When he spoke, it was with an ominous softness.

‘What happened?’

Sidney answered, grievous, wheezing. ‘No warning, man. Paying a whole crew of boys out there. When the time came, no one made a call. Didn’t shout, didn’t do shit.’

‘I did call you,’ East protested.

‘When there was police already banging on the door.’

So Sidney was here to saw him off.

‘Why didn’t they call?’ Fin said it quietly, amused, almost as if he were asking himself.

Sidney jostled East forward unnecessarily. This meant him: this was his why.

‘There was a lot going on,’ East began.

Fin, quizzical: ‘A lot?’

‘Fire trucks. House fire,’ East said. ‘Lots of noise. The ends – Needle, Dap – maybe that’s what they was thinking: police going to the fire. Maybe. I mean, I ain’t spoken to them yet, so I can’t say.’

‘I think your boys know to call when they see a police.’

‘Oh, yes, they know,’ East said. ‘Oh, yes.’

‘And why ain’t you talked to them?’

‘Something goes wrong, stay off the phone,’ East answered, ‘like you taught.’

Fin looked from East to Sidney and back.

‘Was there a fire for real?’

‘I saw smoke. I saw trucks. I didn’t walk and look.’

‘Maybe it don’t matter,’ said Fin quietly, ‘but I might like to know.’ He gave East a hard look and then veiled his eyes. East felt a beating in his chest like a bird’s wing.

A minute passed before Fin spoke again. ‘Close every house,’ he said. ‘Tell everybody. Submarine. I don’t want to hear anything. I hate to say it, but people gonna have to look elsewhere a few days.’

‘I got it,’ said Sidney. ‘But what are we gonna do?’

‘Nothing,’ Fin said. ‘Close my houses down.’

‘All right,’ said Sidney. ‘But how is it this little nigger fucked up, and I’m not getting paid? Johnny neither?’

‘I taught you to save for a rainy day,’ Fin said. ‘And, Sidney, I taught you not to say that word to me. You know better, so why don’t you step out. You hear me?’

Sidney fell back and grimaced. ‘I apologize for that,’ he said, and he turned to pick up his shoes.

‘You too, Johnny. You can go.’ Fin sighed. ‘East, you stay.’

‘You want us to wait for him?’

‘No,’ Fin said. ‘Go on.’

East stood still, not watching the two boys moving behind him. When the door beeped open and they left, the woman was there, outside, barefoot, waiting. She brought in a tray with two steaming clay cups. She stood mute, and something passed between her and Fin, no words, borne like an electrical charge. Then she placed the tray with the two cups on the empty ottoman.

Quietly she eyed East and then turned and left through the same door. Beep.

‘How you doing?’ Fin said. ‘Shook up?’

East admitted it. He was aching where he stood. Tightened up more than ever. His knees felt unstrung. ‘Yeah.’

‘Sit.’

East lowered himself to the second ottoman stiffly and sat beside the steaming tray in the dusky room. Fin spread his shoulders like a great bird. He moved slowly, top-heavy, as if his head were filled with something weightier than brains and bone.

Fin was East’s father’s brother – not that anyone had ever introduced East to his father. Others knew this; sometimes they resented East for it, the protective benevolence he moved under. But it shaped their world too, the special care that was given him, his house, his crew. When East was a child, Fin had been an occasional presence – not a family presence, like the grandmother whose house held a few Christmases, like the aunt who sometimes showed up in bright, baggy church clothes on Sunday afternoons with sandwiches and fruit in scarred plastic tubs. Fin was a visitor when East’s mother was having hard times: to put a dishwasher in, to fetch East to a doctor when he had an ear infection or one of the crippling fevers he now remembered only dimly. Once Fin took East to the Lakers, good seats near the floor. But East didn’t understand basketball, the spitting buzzers and the hostile rows of white people in chairs, and they’d left long before the game was decided.

But since East had grown, Fin was the quiet man in the background. East had never had to be a runner, a little kid dodging in and out of houses with a lunchbox full of goods or bills. He’d been a down-the-block lookout at ten, a junior on a house crew at twelve. He’d had his own yard for two years, directing and paying boys sometimes older and stronger than he was. Not often in that time had he laid eyes on Fin, but often he’d felt the quiet undertow of his uncle’s blood carrying him deeper into the waves.

Did he want to do this? It didn’t matter: it would provide. Did boys respect him because he could see a street and run a crew more tightly than anyone else, or because he was one of Fin’s favorites? It didn’t matter: either way he had his say, and the boys knew it. Was this a life that he’d be able to ride, or would he be drowned in it like other boys he’d kicked off his gang or seen bloody or dead in the street?

It didn’t matter.

‘Try it,’ Fin said.

East touched a cup, and his hand reared back. He was not used to hot drinks.

‘Not ready yet?’ Fin reached for his cup and drank soundlessly. The steam rose thick in the air. ‘Now tell me again why that girl got shot.’

East saw her again, her face sideways on the street. Those stubborn eyes. He could still see them. ‘I tried,’ he said, and then his voice slipped away, and he had to swallow hard to get it back. He stared at the tea, the steam kicking up.