Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

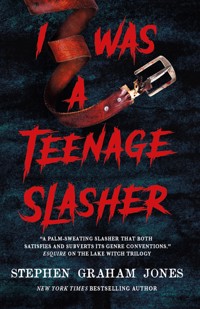

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

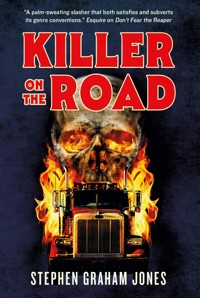

A pulse-pounding and blood-soaked tale of survival on the highway as a hitchhiking teenager is thrust into a deadly game of cat and mouse with a brutal serial killer. Perfect for fans of Grady Hendrix, Rachel Harrison and Keith Rosson. Sixteen-year-old Harper has decided to run away from home after she has another blow-out argument with her mother. However, her two best friends, little sister, and ex-boyfriend all stop her from hitchhiking her way up Route 80 in Wyoming by joining her on an intervention disguised as a road trip. What they don't realize is that Harper has been marked by a very unique serial killer who's been trolling the highway for the past three years, and now the killer is after all of them in this fast-paced and deadly chase novel that will have your heart racing well above the speed limit as the interstate becomes a graveyard. Sixteen-year-old Harper has decided to run away from home after she has another blow-out argument with her mother. However, her two best friends, little sister, and ex-boyfriend all stop her from hitchhiking her way up Route 80 in Wyoming by joining her on an intervention disguised as a road trip. What they don't realize is that Harper has been marked by a very unique serial killer who's been trolling the highway for the past three years, and now the killer is after all of them in this fast-paced and deadly chase novel that will have your heart racing well above the speed limit as the interstate becomes a graveyard.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 359

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Acknowledgments

ALSO AVAILABLE FROMSTEPHEN GRAHAM JONESAND TITAN BOOKS

The Only Good Indians

THE LAKE WITCH TRILOGY

My Heart is a ChainsawDon’t Fear the ReaperThe Angel of Indian Lake

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter

The Babysitter Lives

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Killer on the Road

Print edition ISBN: 9781835415801

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835415832

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: June 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Stephen Graham Jones 2025.

Stephen Graham Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro by Richard Mason.

for my brother Spot,who I can talk trucks with for days

“THANKS FOR THE ride,” the hitcher says, climbing in from the sheeting rain.

“What’s the old joke?” the driver says, clocking his mirror to ease back up to speed. “I ask you—no, you ask me if I’m a serial killer, and I say no, I’m not worried about that. The chances of two serial killers randomly being in the same car are through the roof, right?”

“Something like that,” the hitcher says, taking the towel the driver’s dug up from behind the seat, nodding thanks over it.

The driver clicks his headlights from bright to normal then back again, trying to see through the rain.

“More like I should ask if you know how to handle a submarine,” the driver says, easing them ahead.

“Biblical out there,” the hitcher says, strapping his seatbelt across.

“Belly of the whale,” the driver says back.

“You don’t listen to talk radio, do you?” the hitcher asks, squinting through the blurry windshield at the road ahead of them.

“Maybe I do?”

“Good,” the hitcher says. “Me too. Can’t get enough.”

“Or maybe I don’t.”

“Me either. Hate it. Talking heads, floating voices. Puts me on my meds.”

“You’re medicated?”

“Not right now, don’t worry.”

The driver considers this for a handful of seconds.

“Just to be transparent here,” he finally says, and pushes his hand down alongside his seat, comes up with a chunky snub-nose.

“I get it,” the hitcher says. “Road can be a dangerous place.”

“I don’t usually do this,” the driver says. “Pick someone up, I mean.”

“And I usually don’t manage to catch a ride when it’s raining,” the hitcher says.

“Firsts for both of us, then.”

“Just two killers heading west.”

The driver chuckles, likes that. Switches hands on the wheel and looks over to the hitcher. “Confession time,” he says. “My radio’s actually on the fritz—why I stopped for you. So you can help me stay between the lines. Know any scary stories to keep us awake?”

“Work for my supper, got it,” the hitcher says, scooching down in the seat for a comfortable position then straightening back up.

“I’m driving either way, man,” the driver says. “Just”—easing over for a whirr of the rumble strip on the shoulder—“am I over here or not, right?”

“I could drive, you want,” the hitcher says. “License is good and clean in Wyoming.”

“Thanks, of course, but . . . you know.”

“I get it, yeah,” the hitcher says. “So, a story . . .”

The hitcher narrows his eyes to dredge the right one up.

“You heard the one about the guy picks up a girl who turns out to be a ghost?” he asks.

“You telling me I’m talking to a ghost?” the driver says, very ready to thrill a smile up.

“There’s the one about the vampire thumbing rides at night to get his dinner.”

The driver lifts his revolver again, makes like he’s peering into the back of the cylinder, says, “And here I am without my silver bullets.”

“Think that’s werewolves,” the hitcher says, folding the towel that wasn’t folded before. “You know about the lot lizard who kept working after she was dead, and ended up getting pregnant with something?”

“Sounds like a cautionary tale,” the driver says, raising his hand to shield his eyes from a bright car on the other side of the divided highway.

“Here’s one,” the hitcher says. “You hear it everywhere, last year or two.”

“Everywhere like . . . hobo camps?”

“If this was 1932,” the hitcher says with a tolerant smile. “Rest stops, truckstops. Lock-up. Tunnels when it’s raining like this, or under bridges.”

“This isn’t the lot lizard one?” the driver asks, his disappointment nearly theatrical.

“Better,” the hitcher says. “It’s one of us—dudes looking for rides. Deal is, this Bucketmouth guy climbs in like I just did and after a while he asks you if you’d rather be dead or missing a finger.”

“He just asks it out of nowhere?” the driver says. “Out of the blue, like?”

“Kind of a conversation killer, yeah.”

“Is Bucketmouth his name?”

The hitcher shrugs sure.

“Finger, obviously,” the driver says. “You’ve got ten fingers but just one life. Easy call, especially if it’s hypothetical.”

“Thing is,” the hitcher says, “it’s not. He’ll give you a knife or something to cut it off if you can, then he makes you sit there while he takes it and”—miming a tiny cob of corn—“he eats the meat off it while you watch.”

“A cannibalism story,” the driver says, his lips peeled back from his teeth in appreciation.

“Except this one’s true,” the hitcher says, and opens both his hands, presses them into the dashboard for viewing, all his fingers there through his fingerless gloves, except . . . the pinky on the left.

The driver jerks the car over, away from this, the tires thudding over the reflectors embedded in the shoulder, then he flutters his right hand over his beating heart.

“I’m awake now,” he says, making himself breathe big in and out, the seatbelt tight across his chest from all his moving around.

The hitcher chuckles, his hands still pressed onto the dash.

“You’ve done this before, haven’t you?” the driver says at last.

The hitcher unfolds his pinky finger, waggles it.

“What if you really met this guy, though?” the driver asks, undoing his seatbelt to reset it, guiding the strap back down to the buckle, having to dig and adjust to find it. “No, no—what if it’s you, and this is how you prep me for what’s about to happen?”

“Already had my finger for the day,” the hitcher says, looking at all his own, still spread out perfect on the blue vinyl of the dash.

“Not me,” the driver says, and presses the snub-nose barrel of his revolver against the hitcher’s pinky where it connects to the hand, and pulls the trigger.

The sound in the cab of the car is massive.

The driver drops the revolver to press this finger to the dash, catch it before it can fall into the floorboard. The hitcher reels away, pushing hard with his feet, his butt climbing the seatback, but then he realizes: the gun in his lap.

He fumbles it up, trying to hold it and stop his new stump from gouting blood up into the headliner.

“You, you, you,” he says, and pulls the trigger at the driver again and again.

There was only the one bullet.

The driver lifts the still contracting finger up like thanking the hitcher for it, then inserts it neatly into his mouth, rotating it a little on insertion like getting it just how he likes it.

“Where you headed, mister?” he says as if starting them over, dialing them back to when the hitcher got in. His words a bit muffled by the finger in his mouth, but it’s only the pinky.

The hitcher doesn’t respond, is still climbing his seat.

“What?” the driver answers in his own voice, leaning forward over the steering wheel, the raw end of the finger still protruding from his lips. “You mean this isn’t the highway to hell?”

He laughs and laughs about this, then sucks the finger all the way in.

The hitcher fumbles at his door handle but the lock sucks down.

He elbows the window but is wearing so many layers that they pad his blows.

“What the fuck are you?” he screams to the driver.

“Bucketmouth, evidently,” the driver says around the thick finger. “I know I don’t get to, like, select my own name, that’s not how the big machine works, but what does Bucketmouth even mean?”

He leans forward to inspect his mouth in the rearview mirror, work it open and shut a couple times to confirm that it’s just a normal mouth. Then he sees something that needs attention at the base of his jaw on the right side. He angles his head over so his fingertips can pinch up a skin tag.

He tugs gently on it, then harder, longer.

His whole face peels off, leaves just muscle and fat and tendons and dripping blood, and something cloudy and viscous coating it all, like the saliva of someone who’s been sucking on a Vaseline lollipop.

He inspects himself in the mirror again from all sides, nods that he likes this, yeah. This is good.

He tosses the face he just peeled to the hitcher, who flinches away hard enough that the back of his head shatters the window out at last. The interior of the car swirls into a madhouse, burger trash and receipts and emptied-out Fritos bags whipping around everywhere, then sucking out into the night.

“What are you, man?” the hitcher says, weaker.

“More like who, sir,” the driver says, unlocking the doors with his master control and then reaching across the hitcher to pop the door open, push him out, leave him rolling in their lane, the headlights of the semi behind them coming on fast and unavoidable, the horn blaring at what probably looks like a trash bag of something. At least until it goes under the wheels.

Alone in the front seat, the driver looks in the rearview again, winces when the headlights behind him turn sharply away. Then he angles the mirror onto himself, says, “Bucketmouth?”

He shakes his head in wonder then turns his functional radio on, hums with the Roger Miller coming through, and clicks the headlights off, slips ahead, into the darkness.

THERE MIGHT HAVE been a better way to do it, Harper knows.

Also, she could have packed.

And, just spitballing, but what if she’d thrown less of her mom’s precious collector’s plates across the living room? What if she hadn’t lifted the couch up by one end and, in trying to send it flying after the plates, jammed it against the ceiling?

No way was she taking back what-all she’d said, though.

On Harper’s list of things she hates now and always will, forever amen, around number six or seven would be people simpering back after a big blowup, saying how they didn’t really mean to say that.

What they mean with that, actually? It’s not that they hadn’t meant to say that, it’s that they got pissed enough that they said what they really meant, and now kind of wish they could reel that back in, do you mind? Can we all just forget, pretend that never happened, keep moving forward?

No, Harper tells them in her head. No do-overs, no takebacks.

As of two months ago—graduation—she’s eighteen, so doesn’t have to play nice anymore. Granted, there’s her little sister Meg to keep in mind, who in a perfect world wouldn’t have been watching this big blowup from the hallway, but . . . had Harper had anybody watching out for her when she was in seventh grade? No. It was just and only her, twenty-four/seven, and she made it through . . . not completely unscathed by Mom, but she wasn’t a smoking husk, either. Not yet, anyway.

But she could have packed.

When her mom disappeared back down the hall, came storming back up with Harper’s laundry to throw at her on the porch, yeah, it wouldn’t have been terrible to have held onto some of those dirty clothes. But it had felt so good too, hadn’t it? Flinging it all over the front of the house, screaming how this was a clean break, that she didn’t want any reminders of this place, that she didn’t need any of them, that this podunk Wyoming shitkicker town wasn’t going to hold her back anymore? That she had better opportunities anywhere than this. That her friends were her real family anyway.

That last part . . . Meg hadn’t still been listening from the living room, had she? Because she didn’t mean it that way. Her and Meg would forever be sisters. Just, Harper could not stay in that house even one second longer. Sorry, Meggie. But if Harper made it this long, so can she, right? Anyway, it’s not like Harper can take a little sister along. Really, it’s just her for this big exit. Those friends she calls family would be there for her, but two of them have already zipped their sleeping bags together and taken off for Yellowstone to work for the summer, one of them’s blasting off for college in Salt Lake next month, doesn’t need this kind of distraction, and the other one, her many-times ex Dillon, they aren’t exactly talking, and probably won’t be until the ten-year reunion, which Harper does not plan on attending. So there.

In ten years she’s going to have a room above a bar in Seattle or Los Angeles, her right arm’s going to be full-sleeve, her left arm waiting for her thirtieth birthday, and she’s going to wear mostly leather vests, keep her hair always pulled back unless she’s shooting pool and doesn’t want the night’s mark seeing her eyes.

Her mom isn’t going to have any idea where her daughter is, either. Guaranteed.

Meg? Maybe she can know, sure. No reason to hide from her. But, too, Meg’ll be in college by then, or just getting done, Harper can’t math it out perfect. Maybe Meg’ll even have found the perfect guy or girl by then. They’ll backpack through Australia, send Harper postcards with spiders and snakes and kangaroos on the front, not the elk and bears and cowboys of idiotic Wyoming.

Harper kicks a rock ahead of her, tracks its vaulting gallop down the asphalt into their shared future. Hers and the rock’s.

Her one consolation for the moment is thinking about her mom trying to work the couch down from the support pillar it is now. It’s up there tight. When that puffy arm had caught against the ceiling, Harper had backed off, given it her shoulder, all her hundred and forty pounds plus whatever her rage came to, but the couch hadn’t had even one ounce of budge in it. She’d backed off then, stood in the soft rain of the popcorn acoustic and sparkly glitter scraped off the ceiling.

In fifth grade, her and her dad had blown that ceiling up there together, the air compressor over by the back door in the kitchen so they wouldn’t all asphyxiate, and her mom had said no glitter in the living room, but Harper’s dad had let her sneak a handful into the mix anyway, and it had been beautiful, like twinkles of secret gold.

This of course being five years before Mom ran Dad off.

That of course, Harper figures, being pretty much the official beginning of the end. The last good summer.

Write it in your memoir someday, she tells herself, and passes the rock she kicked. She doesn’t kick it again.

It’s hot now but this is Wyoming in July. Come dark there’ll be a chill. Which is why she’s not going to be outside. Also, if things go right, she’s not even going to be in Wyoming anymore. Maybe if she runs hard enough, if she never looks back, she can forget she’s even from this place at all.

And she’s not fucking crying, okay?

“Happy last summer before real life,” she says to the idea of her mom. “Thanks for all the laughs, it was a riot.”

A big rig grinds past her—the on-ramp to the interstate is right there—and she hunches her shoulders against the dust and sound it’s dragging then sneaks a peek at the back of the trailer. Just to see.

Her dad, whatever trailer he was dragging that week, he would always draw a rough circle in the grime on the back of it, lower right, then lick a different finger, dab some hashmarks in for the idea of numbers. A short slash and a long slash, then—careful not to cut a piece of pie from this circle—and . . . it was a clock. It was supposed to be his way of telling all the tourists on his roads that he was on a schedule, that he had places to be, that he had a family to be getting back to, that he didn’t have time for RVs drifting from this lane to that, for sports cars passing on the right side, for minivans flipping lanes to get to the next tourist attraction twenty seconds sooner.

That’s Harper’s first tattoo, so far: the round, slightly oblong face of a clock on her right scapula. She’d told the guy to just put the hands pointing at whatever time, it didn’t matter. It wasn’t about the time. It was about who she was. It said she had places to be, thanks. Places very much not here.

Another thing that’s going to be out here on the road with her tonight, she knows, is stars. Wyoming stars, which she has to admit she might come to miss someday. Lying under them she’s going to be eleven years old again in the living room, the ceiling above glittering and sparkling.

Too late, just for the gesture of it, just to show she’s committing to this enterprise, she hikes her thumb up for the trucker’s mirrors but he’s already hauling his big wheel over to the left, reaching for a lower gear, to ride the on-ramp into America proper.

When the truck doesn’t slow, Harper lowers her face, thrusts both hands into the kangaroo pocket of her pow-wow sweatshirt—Meg’s, oops—and stifflegs it under the eastbound then westbound bridge to make that big left onto 80 as well.

In her head she does her blinker, and, coast clear, swings her right leg around, pivoting on her left foot, taking that important first step away, into something better, something real. Something not here.

BECAUSE THE STATIES will stop to have words with you for hitching on the actual interstate, the ramps are where all the rides are, Harper knows. Well, the ramps are what work when your mom might be cruising slow through all the pump islands of town.

That’s the way it always works with her mom: I hate you I hate you I hate, followed by I’m sorry I love you come back you’re the most important thing in the world I could never lose you please.

So: the ramp, which is just a ramp by name, not by actually angling up or down more than three or four feet.

Because West Laramie’s a blink-and-miss-it joke, Harper’s the only one sailing her thumb out at five thirty in the blazing afternoon. Which is good. In her current state she doesn’t need any Bobby McGee tagging along.

The first big rig that rumbles past has too much speed to waste it on a runaway who’s probably a minor, and the second and third rigs—a Mack cabover, a Freightshaker like her dad’s—both already have riders perched up in the passenger seat. Yeah, one of those riders is a dog, one’s a woman her dad would have called a seatcover, and all the trucks had sleepers she could have napped in just fine for three hundred miles, but screw it.

Is it the big stenciled feather on her back that’s warning the drivers off? Are Indians automatically trouble? If so, then it’s good she stole Meg’s sweatshirt, isn’t it? Otherwise the drivers would have to wait to ditch her until they saw her hair, her skin, her face.

I could be Mexican, though, Harper says to those drivers, her eyes slit hard at them. Except this is Wyoming, yeah. And except for this big feather on my back. More like a bullseye.

Thanks, Mom.

If these drivers knew her dad had been a gearjammer and white like they maybe are, would they be lining up to give her a ride? Probably to the first exit, yeah. Where they could turn around, trash their schedule to deliver this little girl back to where she belongs.

Screw that noise.

An hour later Harper is sitting by the last reflector pole down the ramp, her back to Laramie, her face west, west, always west. Now she’s thinking it would have been nice to pack some clothes and also her headphones, wherever they are.

Big gestures don’t always involve forethought, though. And anyway, it’s not like this is the furthest away she’s ever made it, right? Her junior year she made it all the way down to Colorado before a waitress called her in for approaching trucks in the back row. According to the cops, that waitress maybe saved her life.

Her comeback when the cops told her that: What life?

The younger one told her yeah, she’d been seventeen once too.

When tires finally crunch onto the shoulder behind her, Harper hauls herself up, no smile, ready to give whatever bluff or attitude she needs to make this work out. Maybe even a smile. Extreme circumstances call for extreme measures, all that.

It’s an old long Thunderbird, faded red with a vinyl roof peeling away in a thousand tiny curls of white.

Her eyes flash to the car’s rearview first of all. It’s how she’s trained: will there be an eagle feather there, or some baby moccasins, a little beaded headdress? All of those would be acceptable, as would a twirling iridescent CD, meant to scatter radar guns. What’ll send her scampering for cover will be a dreamcatcher. What’s there in this Thunderbird is a cross that’s really purple yarn wrapped around and around two popsicle sticks, with a secret and surely meaningful strand of yellow or gold in there.

Don’t run, don’t run, you need this, Harper tells herself, even though her genes have been programmed to know the church is the boogeyman for Indians—it’s the hand that grabs you by the scruff while the other hand’s already drawing back in a fist.

The passenger door opens, takes forever to stop opening because this car is long enough to be a train, practically, and both the passenger and the driver get out that side. For safety.

Harper, her face pleasant, hair threaded behind her ears, tries to see into the backseat. No one. Good. This can work.

The woman approaches first. She’s got this long skirt and sandy-colored beehive do under a scarf—she should be wearing cat-eye glasses, Harper thinks. Next is the acne-scarred white man putting his sports jacket on, trying to guide his combover back into place and get his glasses resettled on his face.

The woman leads with a bottle of water fresh from a cooler, with a glow-bracelet threaded through the label for increased visibility at night.

Shit.

Do-gooders. Holy rollers.

Harper takes the bottle, twists the cap off and takes a polite sip.

“Do you know where it is that you’re going, dear?” the woman says. This is probably their script: the woman carries the conversation load when the hitchhiker is female, so as not to spook her. Or maybe it’s to establish sisterhood or be a mother figure.

The question is a loaded one, of course.

“To hell?” Harper says, to just get it over with.

The man looks back up the on-ramp, his cheeks crinkling around his eyes, his chest thrust out from the way he’s stretching his shoulders back, his hands wrapped into thumb-swallowing fists from the strain.

“Next hundred and fifty miles are—they’re like the Bermuda Triangle for travelers, do you know that?” he says, finally bringing his pasty face around to Harper.

“Thought it was the Snow Chi Minh Trail,” Harper says right back. It’s what her dad used to call 80 in the winter.

“He’s talking about all the people who go missing, dear,” the woman says. “You’ve seen the posters in the windows at the gas station, haven’t you? Not just . . . walking people either. Drivers too.”

“Just because people don’t call to check in doesn’t mean they’re missing,” Harper says. “Just means they don’t want to get found.”

“No, I mean—” the woman starts, then starts again: “One of the young women from our congreg—from our flock, she’s kind of a data expert, see, it’s her job, and she’s identified this stretch of interstate as statistically more—”

“Thanks for the water,” Harper says, being sure they can tell she’s already looking on down the road. “Don’t worry, I recycle.” She tips the bottle off her forehead, saluting them bye, but they’re on a mission, are blind to any and all social cues.

“Just last month,” the man says with apologetic finality, guiding his hair into place again, passing a slick photograph to Harper.

She doesn’t take it but she can’t help but clock it.

It’s the head and shoulders of a dead man in the dry grass of what’s probably the ditch—no, this is deeper into the BLM wasteland, isn’t it? Harper can tell from the snow fence this man’s been leaned up behind, that’s tilting him forward. His eyes are gone, probably taken by birds, and his mouth has been hollowed out as well, and his skin’s been baked to leather. In the winter he’d be a corpsicle, but in summer like this he’s just a mummy.

Harper sucks air in through her teeth, almost a hiss. It’s not so much from the shock of seeing this with no preparation, it’s from—it’s stupid. Right after her dad didn’t come back from his last run, this was where she’d spent all her time: studying what photos she could find of unidentified men found in proximity to the interstate. At first she’d been able to eliminate some of them by hair length, but after a couple of years her dad could have grown his hair down to his shoulders. So now all she had was facial hair versus no facial hair. Her dad had none when he left, and had always been against it, said it creeped him out when he could see it out the bottom of his eye. This dead guy maybe had the same hang-up. Clean-shaven.

“You okay, dear?” the woman asks.

“Scared straight, ma’am,” Harper says. “Thanks, thank you. Wouldn’t have a sandwich for a lonely traveler now, would you?”

Ten minutes later, the Thunderbird people gone, Harper bites into the first of the three sandwiches she was able to talk them out of. It’s pimento cheese, which is paste with chunks in it that are a slightly different temperature, or texture. After two normal chews and four longer, slower ones Harper gags it out, thinking of that dead guy’s dry, empty, open mouth, damn those holy rollers to hell.

“That won’t be me,” she says, making it so by saying it out loud.

And it isn’t her dad either, she adds, in secret.

TWO AND A half sandwiches in her kangaroo pocket now, Harper finally just decides to stand, hoof it. She’s got the glow-bracelet on her wrist, right? Doesn’t that make her practically bulletproof?

Half a dozen steps later, another set of tires crunches in behind her.

Harper cringes, doesn’t need any more salvation, fuck you very much. But, at the same time, she knows she probably should load up on water, if there’s water to be had. And maybe a handful of tissues too, since she’s now committed to walking away from all indoor bathrooms.

She turns, her most pitiful face on like a mask, and it’s—it can’t be. Cropped-short orange hair in the passenger seat, a perfect white smile over the steering wheel. Kissy and Jam? Who are supposed to be in Yellowstone for the whole summer, chasing wolves and tagging bears?

Harper holds her arms out so they can see how flabbergasted she is, how out of the blue this is, and then she holds them there a bit longer, shoulder high, her face trying to maintain the same shocked expression. But she’s processing now: if they were in town for the day, for the weekend, for whatever, then . . . they were in stealth mode? not looking her up? avoiding her?

What kind of bullshit is that supposed to be?

Jam slithers up from the passenger side of the blocky-old four-door used-to-be-white Forest Services looking truck—Park truck, Harper’s just now registering—crosses his arms over the roof and flops his head over to the side like to see Harper better, or slower, make this moment last.

“We leave for two months and you’re already sacrificing yourself to the interstate gods?” he says.

“Harper!” Kissy yells from behind the wheel, tapping the horn three times in celebration, the third time long and loud.

Harper has to smile.

Her hands thrust back into her sweatshirt pocket, she sashays up to Jam’s side—short for ‘James’ since junior high—and leans in to hug him, reaches past him to hold hands with Kissy, which has been her name since forever, for obvious reasons.

“Figured you’d be pregnant already,” Harper says to her.

“Not for lack of trying,” Jam says around the back of his hand and not even close to a whisper, and Kissy hits him in the hip with the side of her fist.

“There’s bears up there!” Kissy says, about Yellowstone.

“Bears and pic-a-nic baskets, yeah,” Harper says, looking down the ramp to a clump of three choppers riding in formation. “Y’all are going back?” she says into the cab real casual, trying not to load it with anything.

“We swung by your house,” Jam says, quieter, shrugging it true. “Your mom was, um, redecorating?”

“She’ll be moving on to my room next,” Harper says, rolling her top lip in between her teeth. “Now that she can do what she wants with it, I mean.”

“I’m sorry,” Kissy says, batting her eyes like she’s a deer in a Disney movie. The bad thing about Kissy, which is maybe the good thing too, is that she’s put together just like the cartoon Pocahontas in the movie Harper took Meg to last week: impossible cheekbones, bustline that won’t quit, shampoo commercial hair. Never mind that she’s not enrolled at Wind River, or anywhere. On all her applications she checks the ethnicity box she has to draw in, “Cherokee Princess.” It kind of fits, sick as it is. It makes her everybody’s grandmother, just, when that grandmother was hot.

“You look good,” Harper says to her. “Pre-pregnancy suits you.”

“This is all I’ve got cooking in me,” Kissy says back, extending her middle finger slow like a bun rising in an oven.

“I’ve missed this,” Harper says. “Been kind of a long summer.”

“Tell them where you went looking for her next,” a voice calls over the backseat, even though the backseat’s . . . empty?

Harper lowers her eyebrows to Kissy about this but is already stepping back to look through the rear window.

Dillon, kicked back across the bench seat, his down-at-the-heel boots chocked up on the passenger side armrest.

“We thought y’all might be . . . back together,” Jam says, as apology.

“And he’s going back to the Park with you now?” Harper says.

“I was worried about you,” Dillon says. “I know how you can be. I mean, if anybody does.”

“You fixed my mom’s couch, didn’t you?” Harper says to him, disgusted.

“I did,” Jam says, raising his hand to take this heat. “We didn’t have loverboy with us yet then.”

“That’s one name for hi—” Harper says, looking up the ramp and catching almost immediately on the side-profile of her mom’s pale Buick, cruising out from under the bridge like she gave the car some pedal a quarter mile back, is just riding that out in silent mode.

Harper rolls to the truck, flattens herself against it, and, easy as anything, Dillon slips the door open, pulls her in, his hand to the jut of her right hip, his other hand guiding her head below the level of the window.

“She’s stopping, she’s stopping . . .” Kissy announces, tight to the rearview, her foot revving the engine even though they’re not in gear.

“Shit shit shit,” Jam says, bouncing in his seat, drumming one hand on the outside of the door.

“Go already!” Harper says from the floorboard of the backseat.

“She’ll know,” Dillon says, and then kicks the door open decisively, takes one step out into the grass, and lets loose with a harsh arc of pee, leaning his whole body back from it.

Halfway through, his staged emergency over, he looks up like just seeing the Buick up there. He turns to it, waves big, probably some other part of him waving as well, and Harper’s mom puts her foot to the gas now. When Dillon leans back in, breathing hard with excitement, Kissy passes a baby wipe back to him.

“You can just pee any time like that?” Jam says, impressed. “Never knew that about you.”

“Full of piss and vinegar, my mom always said,” Dillon says, leaning back to zip up. “That’s half-true, anyway.”

“You could have faked it,” Harper says. “She can’t see detail that fine all the way from up there.”

“That fine?” Dillon says after a beat.

He balls the wipe up, tosses it into the grass.

“Listen, thanks,” Harper says to Kissy and Jam, her voice ramping up to goodbye—no way does she need to be taking any road trips with her ex, thank you—“but y’all probably need to be getting back to—”

“Ho,” Jam says, his hand cupping the side mirror, holding it steady against the engine’s vibrations. “You weren’t the only rabbit hiding in this ditch, were you?”

All of them look back, and, goddamnit: it’s Meg, standing from the drainage part of the ditch she’d evidently ducked down into at the last moment, probably after sneaking out the backseat of their mom’s Buick at the gas station—oh, of course: she saw the Park truck, knew it from Kissy and Jam stopping by, and . . . shit. Here she is, right where she should never be.

She raises a hand hi, her smile sheepish, seed heads floating all around her.

“Caught,” Kissy says, and before Harper can say anything the truck is reversing up the down-ramp, one tire on the shoulder, one on the blacktop, Dillon standing on the running board, his arm wrapped around the window post as easy as anything. Which Harper kind of hates, since it’s kind of precisely what she used to love about him—how he doesn’t have to think about complicated dangerous scary stuff, just does it like it’s the most natural thing ever. In another era he would have stepped up onto a moving train just the same, never had to look down at tracks or the big steel wheels or anything.

Kissy stops right alongside Meg.

“What the hell?” Harper says to her.

Meg shrugs, her lips covering her new braces.

“Mom thinks you’re sleeping in the backseat, still?” Harper goes on, trying to make her eyes hot and mad, not about to cry from seeing Meg.

“You broke my plate too,” Meg says with a shrug, and Harper has to concentrate to keep all these plates spinning in her head. But then it slows enough for her to see it: the one Meg got off that infomercial because the dog on it looked like Sheba, her dog that had got parvo two summers ago. Harper had camped in the backyard with her and Sheba for four nights until . . . until.

“Shit,” Harper says, and reaches through the window to pull Meg’s head to her shoulder. “Shit shit shit, girl. I’m sorry.”

“I tried to put it together, but Mom—Mom—” Meg says, which is the last thing Harper hears before the world becomes sound and stinging gravel: a shiny Kenworth’s taken the left onto the ramp fast to keep its momentum, really dive down onto 80, but that means it’s riding the bright white line of the shoulder. The one their truck is straddling.

The Kenworth’s air horn opens, splitting the afternoon in two, filling all their heads with instant panic, with certain death, and then Kissy straightens her arms against the steering wheel and stomps the pedal in.

For a moment, a lifetime, the truck stands there on its one spinning tire, Jam screaming, his left hand pushing up into the headliner like that can possibly save him, that Kenworth’s grill filling all their mirrors, its horn filling all their heads, but then the Park truck’s one spinning tire catches and they bolt forward, and it doesn’t matter that Harper is trying to clutch onto Meg, to keep her safe. It doesn’t matter because Dillon’s stepped back onto the running board, is cupping her body with his, holding her and Meg both safe. Just another thing he does so natural, without having to even think about it.

Goddamn him.

By the spit-out of the ramp they’re doing forty, the tired engine chugging, smoke billowing behind them, and a half-mile later they’re up to a shuddering unsteady sixty, the truck’s absolute limit, and then Kissy is crying and driving and trying not to hyperventilate.

“Any . . . time,” Dillon says through the open window, still riding the running board, and Kissy eases them off the next ramp, the one that’s all motels and truckstops.

The Kenworth slams past, at speed now, its air horn blasting the whole way.

“I-I think I prefer bears,” Jam says, trying to smile, his eyes shiny.

Kissy glides them into the scrub nobody cares about and leans into the steering wheel, her hair draping down through the shifter and blinker and whatever.

“Thank you,” Harper says to Dillon, over Meg’s head, and Dillon shrugs like it was nothing, is already stepping down, looking ahead, tracking that Kenworth.

IT TURNS OUT that the Park truck Kissy and Jam are driving is why they’re in town. Just for the day. Yellowstone is getting a new fleet, selling off the old, and Kissy’s dad always needs another. Donny, their legendarily gruff supervisor, had given them eighteen hours to Laramie and back for show and tell—breakfast cleanup to last call—to see if her dad wanted the truck.

Turns out, he didn’t. The arrowhead emblem on the door is cool and distinctive, especially half-faded like this one’s, but Park trucks have spent their lives grinding down two-tracks in first gear, are better left to that than trying to come to town, put on a suit and tie.

“So . . . you were here all day today?” Harper says.

“That’s what you get from that?” Dillon says, impressed.

“Family lunches,” Jam says, emphasizing the plural. “As in, over at my mom’s, then my dad’s, then Kissy’s parents?”

“Good to eat something that doesn’t taste like smoke,” Kissy adds, guilty. “But two lunches probably would have been enough.”

“What was the fight about this time?” Dillon says to Harper.

“Usual,” Harper says, eyeing the interstate, all-too-aware Meg is right there listening. “It’s good that it’s almost dark.”

“True that,” Kissy says, patting the truck like the sad thing it is. “Old Whitey here kind of has . . . overheating issues.”

“Interested?” Jam asks, playing. “Our other buyer turned out to be actually smart.”

“I mean,” Harper says, about it getting dark. “Just—we’re already on trucker radar, right? That little stunt on the ramp? All the drivers headed east on 80 know to be on lookout for a truck with a big stupid arrowhead on the door.”

“As in, they want to be sure we make it to our destination?” Jam says, innocent and hopeful as ever.

“As in we’re number one on the shit list,” Dillon says.

His dad’s a driver as well. It was the first thing that brought Harper to him.

“Meaning?” Meg asks, reminding Harper that her little sister was too young to ride the doghouse with her dad on his short runs.

“I think what Harper’s saying,” Kissy says, drilling an index finger theatrically into each of her temples and closing her eyes to better focus her psychic powers, “is that . . . a revenge-minded semi or two might be razzing us.”

“Two inches away at eighty miles per hour,” Dillon says, slamming his open hands past each other to show, the palms scraping. “Horn blasting, bombs flying.”

“Bombs?” Kissy says.

“Bottles of pee,” Harper fills in.

“Fun,” Jam says. “Who needs amusement parks when there’s the Wyoming interstate?”

Harper studies the truckstop across the field.

“Y’all can drop me at Rawlins,” she says. “That’s where you turn up to the Park, right? What, hundred miles?”

Kissy gives a tolerant smiles, says, “Harp, we’re not just going to—”

“And you,” Harper says to Meg. “You’re calling Mom from that phone.”

She points and they all follow that across the field to the payphone koala’d onto the side of the truckstop. The lights glow on over it just then, like Harper staged this.

“But—” Meg tries, only to be stopped by Harper’s serious eyes.

“I can’t take you with me,” Harper says. “I don’t even—I don’t even know where I’m going. It’s not safe.”

“For you?” Meg sort of objects.

“For you,” Harper says. “Why’d you . . . I mean, Mom likes you. You’re the good daughter.”