Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

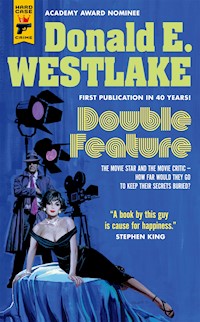

- Herausgeber: Hard Case Crime

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

THE MOVIE STAR AND THE MOVIE CRITIC — HOW FAR WOULD THEY GO TO KEEP THEIR SECRETS BURIED? DOUBLE FEATURE Contains two CLASSIC Donald E. Westlake novellas, A Travesty and Ordo WHAT'S HIDDEN BEHIND THE SILVER SCREEN? In New York City, a movie critic has just murdered his girlfriend – well, one of his girlfriends (not to be confused with his wife). Will the unlikely crime-solving partnership he forms with the investigating police detective keep him from the film noir ending he deserves? On the opposite coast, movie star Dawn Devayne – the hottest It Girl in Hollywood – gets a visit from a Navy sailor who says he knew her when she was just ordinary Estelle Anlic of San Diego. Now she's a big star who's put her past behind her. But secrets have a way of not staying buried… These two short novels, one hilarious and one heartbreaking, are two of the best works Westlake ever wrote. And fittingly, both became movies – one starring Jack Ryan's Marie Josée Croze, and one starring Fargo's William H. Macy and Desperate Housewives' Felicity Huffman. A book by this guy is cause for happiness - Stephen King

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 370

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Acclaim for the Work of Donald E. Westlake!

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Editor’s Note

A Travesty

One: The Adventure of the Missing R

Two: The Affair of the Hidden Lover

Three: The Wicker Case

Four: The Problem of the Copywriter’s Island

Five: The Footprints in the Snow

Six: The Chainlock Mystery

Seven: The Riddle of the Other Woman

Eight: The Secret of the Locked Room

Nine: The Death of the Party

Ten: Memoirs of a Master Detective

Ordo

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Acclaim for the Work of DONALD E. WESTLAKE!

“Dark and delicious.”

—New York Times

“Westlake is a national literary treasure.”

—Booklist

“Westlake knows precisely how to grab a reader, draw him or her into the story, and then slowly tighten his grip until escape is impossible.”

—Washington Post Book World

“Brilliant.”

—GQ

“A wonderful read.”

—Playboy

“Marvelous.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“Tantalizing.”

—Wall Street Journal

“A brilliant invention.”

—New York Review of Books

“A tremendously skillful, smart writer.”

—Time Out New York

“Westlake is one of the best.”

—Los Angeles Times

HARD CASE CRIME BOOKSBY DONALD E. WESTLAKE:

361BROTHERS KEEPERSTHE COMEDY IS FINISHEDTHE CUTIEFOREVER AND A DEATHHELP I AM BEING HELD PRISONERLEMONS NEVER LIE (writing as Richard Stark)MEMORYSOMEBODY OWES ME MONEY

SOME OTHER HARD CASE CRIME BOOKSYOU WILL ENJOY:

JOYLAND by Stephen KingTHE COCKTAIL WAITRESS by James M. CainODDS ON by Michael Crichton writing as John LangeBRAINQUAKE by Samuel FullerTHIEVES FALL OUT by Gore VidalQUARRY by Max Allan CollinsPIMP by Ken Bruen and Jason StarrSINNER MAN by Lawrence BlockTHE KNIFE SLIPPED by Erle Stanley GardnerSNATCH by Gregory McdonaldTHE LAST STAND by Mickey SpillaneUNDERSTUDY FOR DEATH by Charles WillefordA BLOODY BUSINESS by Dylan StruzanTHE TRIUMPH OF THE SPIDER MONKEYby Joyce Carol OatesBLOOD SUGAR by Daniel Kraus

DoubleFEATURE

byDonald E. Westlake

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-143)First Hard Case Crime edition: February 2020

Published byTitan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark StreetLondon SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

Copyright © 1977 by Donald E. WestlakeOriginally published as Enough

Cover painting copyright © 2020 by Paul Mann

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-78565-720-7E-book ISBN 978-1-78565-721-4

Design direction by Max Phillipswww.maxphillips.net

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

For Aram Avakian, fondly, this two-reeler.

Editor’s Note

Donald Westlake originally published this book under the somewhat cryptic title Enough, and opened it with a quote from The Devil’s Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce: “Enough: too much.” This did not make the title less cryptic. If you picked the book up when it was new, it’s possible you might have known that just two years earlier Westlake had published another book punningly titled Two Much. But did that explain this new title? It did not.

This book, which contains two original novellas (two of Westlake’s very best), is a favorite of mine, and when we launched on our project of bringing the best of Don’s undeservedly forgotten work back into print (“The difference between in print and out of print,” Don once emailed me, “is precisely the difference between life and death”), I was determined to include this book.

But what to do about that title? Oh, we could have left it alone. But detached from its moment in time and its proximity to Two Much, it really didn’t make any sense. So I huddled with Abby Westlake and we brainstormed several dozen possible new titles, focusing on the fact that the two novellas in this book both are intertwined with the world of film. Finally, I stumbled upon the title that stuck. “Of course, Double Feature,” Abby wrote. “It even sounds like a Don Westlake title.”

I hope it does. And I hope Don wouldn’t object to this modest tinkering. I take some comfort from his having tolerated such things with good grace and good humor while he was alive. Remind me to tell you the story of the turnip someday.

Charles Ardai New York City, 2020

A TRAVESTY

If once a man indulges himself in murder, very soon he comes to thinklittle of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking andsabbath-breaking, and from that to incivility and procrastination.

THOMAS DE QUINCEY“MURDER CONSIDERED AS ONE OF THE FINE ARTS”

ONEThe Adventure of the Missing R

Well, she was dead, and there was no use crying over spilt milk. I released her wrist—no pulse—and looked around the room, while fragments of imaginary conversations unreeled in my mind:

“And you say you hit her?”

“Well, not that hard. She slipped on the floor, that’s all, and smacked her head on the coffee table.”

“As a result of you hitting her.”

“As a result of her polishing the goddam floor all the goddam time.”

Laura’s clean jagged style had, as a matter of fact, killed her more than anything else. What kind of bachelor girl apartment was this, with its hulking glass coffee table and chrome lamps and white vinyl chairs and bare black floor? Where were the pillows, the furs, the drapes and hangings, the softnesses? Sterile cold hardness everywhere; it might as well be an art gallery.

“But you did hit her, is that right?”

“But it was an accident!”

If it were an accident, it might just as well have happened when I was somewhere else. I wasn’t here at all, officer, I was, uhh… Screening a film. Yes, at home by myself. Yes, I do that all the time, it’s part of my job.

I got to my feet, studying the room. If I weren’t here, what would be different?

Well, that glass, for one. It wouldn’t be standing on the murderous coffee table with Jack Daniels in it and my fingerprints all over it.

Fingerprints. Well, there’d be fingerprints everywhere in this highly polished apartment, wouldn’t there?

“Yes, officer?”

“Do you know a Miss Laura Penney?”

“Yes, I do, casually.” Casually: “Is something wrong?”

“Have you been to her apartment?”

“A few times, I suppose, picking her up for a screening.”

Fine. I took the glass to the small kitchen, washed it, put it away, and headed for the bathroom to study the medicine chest. Razor, shaving cream, toothbrush; nothing that would lead anybody to—

Wait a minute. That little medicine bottle with the drugstore label, isn’t that—?

It is. My Valium, with my name typed on the prescription label: “Carey Thorpe, 1 as required for stress.” So I took one—if this wasn’t a situation of stress there is no such thing—and pocketed the bottle.

Nothing else in here, so onward quickly to the bedroom. Clothing, yes. A couple of shirts, a tie, my Emperor Nero cufflinks, some shorts, my other blue sweater—

Socks? Black, one size fits all, they could belong on anybody’s feet, so leave them. This is becoming a pretty hefty package as it is.

Anything else? Bed-table drawers, with their anonymous drugstore items. Nothing under the bed, not even dust. Fin.

Back to the living room, with my armload of dry cleaning, and Laura spread lifelike on the glossy floor, a scene from almost any John Carroll-Vera Hruba Ralston flick. This side of her looked perfectly fine.

Into my coat. Into my topcoat, distributing shirts and shorts and ties into various pockets, wrapping the sweater around my waist under all the coats. Thank God it was February, and perfectly normal to look lumpy and bulky.

Gloves on, and one final look around. Oh, God, the letter from Warner Brothers, announcing the re-release of some hoary chestnut. My name was on it, and a date making it clear the thing couldn’t have arrived earlier than today. I snatched it up and headed for the apartment door.

And what was the movie again, the one they were reissuing? I gave the letter a quick scan: A Slight Case of Murder.

Oh, really. Stopping, I gazed heavenward; or at least ceilingward. “Come on, God,” I said. “That’s beneath you.” And I got out of there.

* * *

Until the night Laura Penney did herself in most of the violence I’d known had been secondhand. Carey Thorpe is the name, and if that rings no bells you aren’t a truly serious student of the cinema. I’ll admit it’s easy to miss my general film reviewing, in publications such as Third World Cinema and The Kips Bay Voice, but my first book, Author and Auteur: Dynamism And Domination In Film, was an alternate selection of Book Find Club in the summer of 1972, and last year my second book, The Mob at the Movies: Down from Rico to Puzo, got universal raves.

Born in Boston in 1942, I came to consciousness concurrently with television. Being a spindly youth, I spent most of my childhood in front of the box, watching whatever the program directors thought fit to show me. Old movies were the mainstay of local programming then, so by 1960 when I went off to college (Penn State; anything to get away from home and family) I knew more about movies than Sam Goldwyn and less than him about anything else.

College, of course, was full of other spindly youths just like me. Perhaps our predecessors in the dorms had discussed sex and beer and goldfish-swallowing, but we discussed Hitchcock and Fuller and Greta Garbo (why did she agree to make Two-Faced Woman?). In my sophomore year my film reviews were appearing in the college paper, in my junior year my first general piece—“Billy Wilder: The Smile In The Skull”—was accepted by Montage Quarterly (twenty-five dollars and two contributors’ copies, both ripped by the mailman), and when I got my degree in American Lit I moved directly to New York City, typewriter in hand, where I’ve been ever since.

Fortunately, my maternal grandmother passed away just before I passed out of college, leaving me a trust fund with an income of about fifteen thousand a year. Unfortunately, the old bitch mistrusted me as much as she liked me, and tied up the fund so thoroughly with banks and lawyers that I can’t ever get at the principal. (Believe me, I’ve tried.) Nevertheless, the fifteen G a year has been a reasonably comfortable base, and over the last several years my writing has brought in about as much again, so I’ve lived moderately well.

On the other hand, I’d prefer to live very well, and I’d been hoping to make a killing (excuse that) with From Italy With Love. It had seemed to me America was ready for a big glossy photo-filled coffee-table book on Italian Neo-Realism of the postwar era, but so far I haven’t been able to get together with a publisher. I’ll admit seven hundred stills from Shoe Shine, Bicycle Thief, Open City and Paisan might get a little depressing, but what about all those sexy women in their tattered dresses? Sometimes I don’t understand the publishing industry.

I met my wife-to-be, nee Shirley Francesconi, about a year after I moved to New York, at a press screening. She was two years older than I and living with a drugs-politics-8mm freak, so we knew each other only socially for a year or so, and if I’d had any sense I’d have left it that way. But then her freak got busted on possession and went away for an extended rest, so we dated a while and then we lived together and then we got married and then we found out we hated each other.

The only reason we stuck it seven years instead of seven days is because my family thought Shirley was terrific. In fact, when the split finally did come last year it wasn’t to her own folks over in Queens that Shirley went home, it was to mine up in Boston. She’s been there ever since, moving slowly in the direction of divorce and annoying me about money.

The money problem is unfortunately complicated by the fact that she left while I was still high on From Italy With Love. I’d raved a lot about the vast sums that book would bring in, and Shirley wants some of it. My family is well off—my father’s an insurance company executive, he’s had his five square meals every day of his life—and they’re encouraging her to squeeze me. How’s that for a super family?

Then there’s the kids. It’s perfectly true I’m no good as a father, but I never claimed I’d be any good. If Shirley’d just gone ahead and taken the goddam pill like she was supposed to there wouldn’t be any kids, but oh, no, the pill gave her migraine. Migraine! The pill maybe gave her migraine, but the diaphragm gave her a daughter named Rita and the foam gave her a son called John, and whose fault is that? Let my parents go on supporting them if they want, who I want to support is me.

So that’s where we stand; or where we stood until Laura took that header. I’m no monk, I like female companionship, but for all I know Shirley has private detectives on me—she’ll do anything to strengthen her position for that inevitable day in court—so I impressed on both my girls the necessity for maintaining tight security. We didn’t live together, we didn’t obviously date a lot, and of course I’d explained to each of them that I’d occasionally have to take other women to screenings or press parties. (The two girls also didn’t know about one another. Laura and Kit were nodding acquaintances, with no reason ever to confide in each other, so I was about as safe as anybody ever is in this vale of tears. It was even possible to take one of my girls to a premiere attended by the other, with no suspicions raised.)

Well, all that had now come to an end. Laura, who’d at first come on as the most rabidly independent of Women’s Lib types, had been complaining more and more about our secret life, comparing herself to Back Street and other absurdities, wanting to know why I didn’t just get the divorce over and done with (why hurry a finish that could only be costly and difficult for me?) and even threatening once or twice to blow the whistle herself with Shirley. Of course she didn’t really mean it, but it was upsetting to hear her talk that way, and in fact it was a repetition of the same threat that had caused me to lose my temper tonight and pop her one, etc.

“You say Miss Penney threatened to tell your wife about this affair?”

Mm. I was right to get clear of this, as quickly and quietly as I could. So out of the apartment I went, smearing the doorknobs with my gloved hand, checking the street before leaving the building, and walking all the way over to Sheridan Square before hailing a cab to take me home.

Where I found several messages waiting on my telephone answering machine. After divesting myself of my coats and excess wardrobe I made a drink and sat at the desk to listen.

The first was a nice female voice with a British accent: “Mr. Gautier’s office calling Mr. Thorpe, in re screening on the twentieth. Could you possibly make it at four instead of two?”

I’d rather. And since I was unexpectedly dateless for that screening, perhaps the owner of the nice British accent would like to join me. Reaching for pencil and paper, I made a note to call back, while listening to the second message, from Sogeza “Tim” Kinywa, editor of Third World Cinema: “Sogeza here, Carey. Have you got a title yet on the Eisenstein piece?”

No, I didn’t. I was about to make another note when the third message started: “Oh, you’ve left already. I wanted to remind you to bring the Molly Haskell book, but never mind.”

Well. A strange sensation that, hearing a voice from beyond the grave. I erased the tape, finished my drink, and went to bed.

* * *

My street door intercom doesn’t work. I’ve talked to the super about it, but he only speaks some fungoid variant of Spanish understood exclusively on a six-mile stretch of the southern coast of Puerto Rico. I’ve also talked to the landlord, an old man with a nose like a tumor, and his response was the same as to anything his tenants say to him; a twenty-five minute diatribe on economics, expounding a theory so arcane, so foolish, so contradictory and so absurd that I’m surprised the government has never tried it. Or maybe they have.

In any event, when the bell rang at nine-thirty the morning after Laura’s accident I couldn’t find out who it was before letting them in, but who could it be other than the police? Wouldn’t they automatically question all of Laura’s friends, everybody in her address book? Bracing myself, I left my half-eaten omelet and buzzed them in.

Him in. When I opened the apartment door and listened, only one set of footsteps was trudging up the stairs. But didn’t cops always travel in pairs?

Apparently not. When he rounded the turn at the landing I saw a stranger, a chunky middle-aged man in brown topcoat and black hat, looking something like Martin Balsam in Psycho. And coming up the stairs toward me; so I should quick put on my Granny drag and run shrieking out to stab him.

In fact I should have, but of course I didn’t. Instead, I stood in my doorway looking open and honest and innocent and friendly, and when he reached the top of the stairs I said, in a we’re-here-to-help-you manner, “Yes?”

“Morning,” he said, and smiled. He was puffing a bit from the climb, and seemed in no hurry to get his words out. “Mr. Thorpe, isn’t it?”

“That’s right. Can I help you?”

“Well, sir,” he said, “I think it’s the other way around. I think I can help you.”

Not a cop? What was he, some sort of salesman? I said, “What’s this about?”

“This,” he said. Taking a white envelope from inside his coat, he extended it toward me.

Frowning, I said, “What’s that supposed to be?”

“You left it behind.” He was still smiling, in a casual self-contained way. “Last night,” he added.

“Last night?” Unwillingly I took the thing from him and turned it over to see what was written on the other side. Return address: Warner Brothers, 666 Fifth Ave. Neatly centered, neatly typed, my own name and address.

The envelope! I’d remembered the damn letter, but not the envelope. Where had it been?

He answered my unasked question: “Under her.”

“Um,” I said.

“Why don’t we talk inside?” he suggested, still smiling, and walked into the apartment. I had to move aside or we would have bumped. Then I closed the door and followed him into the living room, where he stood nodding and smiling, looking at the movie posters, the one wall of exposed brick, the mirrored alcove that gives the apartment its illusion of space, the projector and screen set up at opposite ends of the room, the unfinished breakfast on the small table by the kitchenette. “Nice place,” he said. “Very nice.”

I moved reluctantly closer to him. He didn’t look like cops in the movies, but what else could he be? “Are you from the police?”

He gave me a quick amused glance. “Not exactly,” he said, and sat down on the sofa. “The fact of the matter is, I’m a private investigator.”

“A private detective?” Several thousand private eye films swirled through my head, most of them starring Dick Powell.

“I was on surveillance last night,” he told me, “outside that apartment.”

I didn’t feel like standing any more. Sinking into my leather director’s chair I said, “So she did put a tail on me.”

His smile grew puzzled. “What say?”

“My wife.”

“Oh, well,” he said, “I wouldn’t want to make trouble for an innocent party. No, sir, it didn’t have anything to do with you. It was Mrs. Penney’s husband put the agency on the job.”

“Husband?” I’d known Laura had at one time been married, but everybody has a marriage or two somewhere in their past and I’d always assumed hers was long since over and done with. “You mean, she was still married?”

“That’s my understanding,” he said. “Legally separated, I believe.”

And she’d been nagging me to break the old ties. Now I saw the whole plot; she’d hold on to husband number one until I was lined up to take his place. Devious devious women, they’re all alike. Josef Von Sternberg knew what he was talking about.

The detective spoke through my interior monologue. “The point is, I was there. I watched the two of you go into the building, and then quite some time later I watched you come out alone, and I must say, Mr. Thorpe, rarely have I seen a man act as guilty as you did. I didn’t know what it was all about, of course, but I thought probably I ought to keep an eye on you.”

“You followed me.”

“That’s just what I did,” he agreed. “And I noticed another peculiar thing. You must have let half a dozen empty cabs go by, but then when you got to Sheridan Square you were suddenly in a real frantic rush to hail a cab and jump in and holler out your address.”

He paused, with a bright alert smiling look, as though offering me a chance to compliment him on his powers of observation. I refrained.

He went on. “Well, it seemed to me you didn’t want anybody tracing you from Mrs. Penney’s apartment, and I thought that a little peculiar. So I followed you uptown here, and waited to see which lights went on, and got your name from the doorbell. You really ought to ask who’s there before you let anybody in, you know, just as a by-the-by.”

“The intercom’s broken.”

“Then you ought to get it fixed. Believe me, it’s my business and I know, you can’t have too much security.”

“I’ve talked to the super and the landlord both. Wait a minute! What are we talking about?”

“You’re right,” he said, “I got myself off the subject. I’m a bug on safety, I take all kinds of precautions for myself and I’m all the time pushing safety on everybody else. Let me see, now. After I got your name from the doorbell I went back downtown and let myself into Mrs. Penney’s apartment.”

That surprised me. “You had a key?”

“Well,” he said, with another of his little smiles, “I have a whole lot of keys. Generally there’s one for the job.”

“You broke in, in other words.”

“Well, sir, Mr. Thorpe,” he said, “I don’t think you ought to start using harsh words, you know. There’s two of us could do that.”

“All right, all right. Get to the point.”

“Well, you know what I found in the apartment.”

“This envelope,” I said, waggling the fist in which I had it imprisoned.

“Yes,” he said, “and a body on top of it. From the marks on the coffee table and the floor, it looked to me as though there’d been some sort of fracas. You struck her—there’s a bit of gray spot on the side of the jaw, she was dead before it could swell up any—and she hit her head on the coffee table going down.”

“It was an accident,” I said.

He did a judicious pose, pursing out his lips and stroking the line of his jaw; Sidney Greenstreet. “That’s a possibility,” he said. “On the other hand, you did run away, and you did try to cover your presence in the apartment, and if you’ll look at this picture here you’ll see you do just look guilty as all hell.”

From inside his coat he had taken a photograph, which he now leaned forward to extend toward me. I took it, with the hand not crushing the envelope, and looked at a grainy but recognizable black-and-white picture of myself emerging from Laura’s apartment building. By God, I did look guilty as all hell, with my mouth open and eyes staring and head half-twisted to look over my shoulder. I also looked very bulky, as though I’d just stolen all the silver. Mostly I reminded me of Peter Lorre in M. “I see,” I said.

“Infrared,” he told me. He seemed very pleased with himself. “The negative’s in my desk at the office.”

I looked up from my own staring eyes into his calmly humorous ones. “What now? What are you going to do?”

“Well, sir,” he said, “I think of that as being up to you.”

And suddenly we were in a situation I recognized from the movies. “Blackmail,” I said.

He looked a bit offended. “Well, now,” he said, “there you go with the harsh words again. I just thought you might be interested in buying the negative, that’s all.”

“And your silence?”

“I wouldn’t want to get a man in trouble, if I could avoid it.” He shifted his bulk on the sofa. “Now, I’m supposed to turn in my report by twelve noon, and it seems to me I could handle it one of two ways. Either I could say a gentleman—that would be you—brought Mrs. Penney home but left her at the street door and went away, or I could report that you went in with her and came out without her and please see photo attached.”

I said, “How much?”

“Well,” he said, “that’s a very rare photograph.”

“And I’m a very poor man.”

He chuckled at me, disbelievingly. “Oh, come along now.

You’ve got a nice place in a rich part of town, you’ve—”

“This isn’t a rich part of town. A couple blocks west of here is rich, but not here.”

“This is the Upper East Side,” he informed me, as though I didn’t know where I lived.

“Look,” I said. “You just walked up the stairs yourself, do you think they have walk-ups in a rich part of town?”

“On the Upper East Side of Manhattan they do. Besides, you’re a writer.”

“I’m a movie reviewer. There isn’t any money in that.”

“You’ve had books out.”

“Film criticism. Did you ever see a book of film criticism on the best-seller list?”

“I don’t believe I’ve ever seen the best-seller list,” he said, “but I do know from my years with the agency that successful writers tend to have nice pieces of money about themselves.”

“I don’t,” I said. “For God’s sake, man, you’re a detective, surely you could check into that, find out if I’m a liar or not. I’ll show you my checkbook, I’ll show you letters from my wife screaming for money, I’ll show you my old income tax returns.”

“Well, sir,” he said, “if you’re too poor, I think I’d be better off going for the glory of making the arrest.”

A cold breeze touched me. “Wait a minute,” I said. “I didn’t say I don’t have any money. Obviously, if I can afford to pay I’d rather do that than go to jail. It just depends how much you want.”

He frowned at me. He studied me and thought it over and glanced around the living room—and to think I’d been pleased at how expensive I’d made the place look—and at last he came to a decision: “Ten thousand dollars.”

“Ten thousand dollars! I don’t have it.”

“I won’t bargain with you, Mr. Thorpe.” He sounded rueful but determined. “I couldn’t falsify my report for a penny less.”

“I don’t have the money, it’s as simple as that.”

He heaved himself to his feet. “I’m truly sorry, Mr. Thorpe.”

“I’ll tell them, you know. That you tried to blackmail me.”

He gave me a mildly curious frown. “So?”

“They’ll know it’s the truth.” I jammed the photograph into my trouser pocket. “I’ll have this picture for evidence.”

He shrugged and smiled and shook his head. “Oh, they’d probably believe you,” he said, “but they wouldn’t care. Funny thing about police, they’d rather catch a murderer than a blackmailer any day in the week.”

“They’ll have both. I may go to jail, but you’ll go right along with me.”

“Oh, I don’t think so.” He could not have been more calm. “I’d be their whole case, you know,” he said. “Their star witness. I don’t think they’d want to cast any aspersions on their own star witness, do you? I think you’d generally be called a liar. I think generally people would say you were doing it out of spite.”

I thought. He watched me thinking, with his curly little smile, and finally I said, “Two thousand. I could raise that somewhere, I’m sure I could.”

“I’m sorry, Mr. Thorpe, I told you I won’t bargain. It’s ten thousand or nothing.”

“But I don’t have it! That’s the Lord’s own truth!”

“Oh, come on, Mr. Thorpe, surely you’ve got something set aside for a rainy day.”

“But I don’t. I’ve never had the knack, it’s one of the things my father’s always hated about me. He’s the squirrel, I’m the grasshopper.”

He frowned, deeply. “What was that?”

“I don’t save up my nuts,” I explained, “or whatever grasshoppers save up. You know, you know, the children’s story. I’m the one that doesn’t save.”

“Well, Mr. Thorpe,” he said, “it seems to me you should have listened to your father.” And turning away, he crossed the room toward the front door.

I should have killed him, that would have been the most sensible thing to do. Picked up something heavy—that can containing North By Northwest, for instance—and brained him with it. Unfortunately, I wasn’t sufficiently used to being a killer, so what I did was grit my teeth and get to my feet and say, “Wait.”

He waited, turning to look at me again, the same patient smile on his face, letting me know I could have all the time I needed. But that’s all I could have.

I said, “I’m not sure I can do it. I’ll have to borrow, I’ll have to—I don’t know what I’ll have to do.”

“Well, sir,” he said, coming back to me, “I don’t want to make things difficult for you if I can possibly avoid it. Here’s my card.”

His card. I took it.

He said, “You call me at that number before eleven-thirty if you decide to pay.”

“You mean, if I can pay.”

“Any way you want,” he said. “I’d mostly like a cashier’s check, made out to bearer.”

“Yes, I suppose you would.” I looked at the card he’d given me. Blue lettering read Tobin-Global Investigations Service—Matrimonial Specialists. In the lower left was a phone number, and in the lower right a name: John Edgarson.

“If you do call,” John Edgarson told me, “ask for Ed.”

“I’ll do that.”

“And Mr. Thorpe,” he said, “do try to look on the bright side.”

I stared at him. “The bright side?”

“You’ve had an early warning,” he told me. “If you decide not to pay, you’ve got almost three hours’ head start.”

* * *

It’s amazing what you can do in an hour when your life depends on it. By eleven o’clock I’d converted into cash the following:

Savings account

$2,763.80

Checking account

275.14

To pawnshops: (Projector 120.; Leica camera 100.; 8mm camera 70.; portable tape unit 160.; 8mm projector 50.; stereo system 180.; typewriter 50.; watch 40.; wedding ring & jewelry 90.)

860.00

Films, posters, stills, etc.

450.00

Loan from publisher against future earnings

1,500.00

$100. bad checks to liquor store, florist, grocer, dry cleaner, barber & hardware store

600.00

GRAND TOTAL

6,448.94

Needed

10,000.00

Shortage

3,551.06

Eleven o’clock. Five after eleven. I was back in my apartment, my pockets full of cash. But where was I going to get three thousand five hundred fifty-one dollars and six cents?

My grandmother’s trust fund? Not a chance. I’d cried wolf with the people at the bank two or three times already, and they’d made it perfectly clear my well-being didn’t matter to them one one-hundredth as much as the fund’s well-being.

My father? Another blank. He had the money, all right, and plenty to spare, but even if he was willing to help—which he wouldn’t be—the cash would never get here from Boston in the next twenty-four minutes. Besides, if I did ask him the first thing he’d say—even before no—would be why.

Would Edgarson take less? Six thousand dollars in the hand was surely better than ten thousand dollars in the bush. I dialed the number on the card he’d given me, and when a harsh female voice answered with the company’s name I asked for Ed. “Minute,” she said, and clicked away.

It was a long minute, but it finally ended with a too-familiar voice: “Hello?”

“Edgarson?”

“Is that Mr. Thorpe? You’re a few minutes early.”

“All I can raise is, uh, six thousand, uh, dollars. And four hundred. Six thousand four hundred dollars.”

“Well, that’s fine,” he said. “And you’ve still got twenty minutes to get the rest.”

“I can’t. I’ve done everything I could.”

“Mr. Thorpe,” he said, “I thought we had an understanding, you and I.”

“But I can’t raise any more!”

“Then if I were you, Mr. Thorpe, I’d take that six thousand four hundred dollars and buy a ticket to some place a long way from here.”

South America. The Lavender Hill Mob. But I liked the life I had here in New York, my career, my girlfriends, my name on books and magazines. I didn’t want to run away to some absurd place and learn how to be somebody else.

“Well, goodbye, Mr. Thorpe,” the rotten bastard was saying, “and good luck to you.”

“Wait!”

The line buzzed at me; Edgarson, politely waiting.

“Somehow,” I told him. “Somehow I’ll do it.”

“Well, that’s fine,” he said. “I’m really relieved to hear that.”

“But it might take a little longer. You can give me that much.”

He sighed; the sound of a just and merciful man who knows he’s being taken advantage of but who is just too darn good-hearted to refuse. “I’ll tell you what I’ll do, Mr. Thorpe,” he said. “Do you know a place in your neighborhood called P. J. Malone’s?”

“Yes, of course. It’s three or four blocks from here.”

“Well, that’s where I’ll have my lunch. And I’ll leave there at twenty after twelve to go turn in my report. Now, that’s the best I can do for you.”

An extra twenty minutes; the man was all heart. “All right,” I said. “I’ll be there.” And I broke the connection.

And now what? I went to the john to pop another Valium—my second this morning—and then I sat at my desk in the living room, forearms resting where my typewriter used to sit, and waited for inspiration. And nothing happened. I blinked around at my pencils and reference books and souvenirs and trivia, all the remaining bits and pieces of the life I was on the verge of losing, and I tried to think how and where to get the rest of that damned money.

From my brother Gordon? No. My sister Fern? No. Not Shirley, not Kit, none of my friends here in New York.

It was too much money, just too much.

What story could I tell my father? “Hello, Dad, I want you to wire me four thousand dollars in the next ten minutes because—” Finish that sentence in twenty-five words or less and win…a free trip…a free chance to stay home.

There was a pistol on my desk; not a real one, a mock-up that had been used in a movie called Heller In Harlem. I’d watched some of the filming uptown, for a piece in Third World Cinema, and the producer had given me this pistol as a kind of thank-you. His name and the name of the movie and my name and a date were all inscribed on the handle.

I picked up this pistol, hefted it, turned it until I was looking into the barrel. Realistic little devil. If it actually were real I could kill Edgarson with it.

But it wasn’t real. So there was only one thing to do.

“This is a stick-up,” I said.

The teller, a skinny young black girl with her hair in rows of tight knots like a fresh-plowed field, looked at me in amused disbelief. “You’re putting me on, man.”

“I have a gun,” I said, drawing it out from beneath my topcoat lapel and then sliding it back out of sight. “You’d better read that note.”

It was a note I’d worked on for nearly fifteen minutes. I’d wanted the strongest possible message in the fewest possible words, and what I had eventually come up with—derived from any number of robbery movies—was printed in clear legible block letters on that piece of paper in the teller’s hand, and what it said was:

MY BABY WILL DIE WITHOUT THEOPERATION. PUT ALL THE MONEYIN THE SACK, OR I’LL KILL US BOTH.

I realize there was a certain ambiguity in that word “us,” that I might have been threatening either to kill the teller and myself or my baby and myself, but I was relying on the context to make the message clear. My baby wasn’t present, but the teller was.

The only sack I’d had available, unfortunately, had originally come with a bottle of champagne in it, and in white lettering on its green side it clearly stated Gold Seal Charles Fournier Blanc de Blancs New York State Champagne. I’d been using it to hold the tiles in my Scrabble set. I knew it wasn’t quite the right image for somebody trying to establish himself as driven to crime by the financial crisis of his baby’s operation, but I was hoping the note and the gun and my own desperate self would carry the day.

I also had the impression, from some newspaper article or somewhere, that banks were advising their employees—telling their tellers—not to resist robbers or raise any immediate alarm. They preferred to rely on their electronic surveillance—the photographs being taken of me at this very instant, for instance—and not risk shoot-outs in banks if they could possibly avoid it.

Well, this time I was ready to have my picture taken. The clear-glass hornrim spectacles on my face were another movie souvenir, the black cloth cap pulled low over my forehead had just been purchased half a block from here, and the pieces of tissue stuffed in on both sides of my face between cheek and lower gum altered my appearance just as much as they’d altered Marlon Brando’s in The Godfather. So click away, electronic surveillance, this is one picture I won’t have to buy back.

In the meantime, the teller was reading. Her eyes had widened when I’d flashed the pistol, but they narrowed again when she studied the note. She frowned at it, turned it over to look at the blank back, picked up the champagne sack and hefted it—an R fell out, dammit—and said to me, “You sure you on the level?”

“Hurry up,” I hissed at her, “before I get nervous and start shooting.” And I flashed the gun again.

“You’re nervous, all right,” she told me. “You got sweat all over your face.”

“Hurry up!” I was repeating myself, and running out of threats. Once a toy gun has been brandished, there’s nothing left to do with it; brandishing is its entire repertoire.

Fortunately, nothing else was needed. With an elaborately unruffled shrug—I envied her calm under pressure—the teller said, “Well, it’s not my money” (my point exactly), and began to transfer handfuls of cash from her drawer to the sack.

At last. But everything was taking too long. The big clock on the wall read five minutes past twelve and I was a long long way from P. J. Malone’s. (I’d thought it better to do my bank robbing outside my own immediate neighborhood.) I wanted to again urge speed on the girl, but I was afraid to emphasize even more the contrast between her calm and my frenzy so I remained silent, jittering from foot to foot as wads of twenties and tens and fives disappeared into my nice green sack.

She filled it, till it looked like Long John Silver’s Christmas stocking, and then she pulled the little white drawstrings at the top and pushed the sack across the counter to me. “Have a nice day,” she said, with an irony I found out of keeping under the circumstances. She might not be taking this seriously, but I was.

* * *

I was three minutes late but Edgarson was still there, lunching at his leisure in a high-sided booth at the back. I slid in across from him and he gave me his encouraging smile, saying, “There you are. I was beginning to worry about you.”

“Save your worry.” In his presence I realized how much I hated him. I’m not used to being helpless, at the mercy of another person, and if I ever had the chance to even the score with this bastard I’d leap for it.

He must have seen something of that in my face, because he became immediately more businesslike, saying, “You have the money?”

“You have the negative?”

“I sure do.” He withdrew from inside his coat a small envelope, opened it, held up an orange-black negative, and then put it back inside the envelope.

“I’ll want to inspect that,” I said. (Scenario: He hands me the negative, I pop it into my mouth and swallow it. Then what does he do?)

But he was smiling at me and shaking his head. Revised scenario: He keeps the negative, mistrusting me. “First you give me the money,” he said. “Then you can inspect this picture all you want.”

“Oh, all right.” Reaching into my pockets, I said, “I didn’t have time to get a cashier’s check. You won’t mind cash, will you?” Fistfuls of the stuff began to pile up on my paper place mat. Even Edgarson lost his bucolic cool at that. Staring at the money, he said, “Well, I’ll be damned. No, I don’t mind cash, not at all.”

The waiter arrived then, gave the money an astonished look, and said, “Did you intend to order anything, sir?”

“Jack Daniels,” I said. “On the rocks.”

“Just one glass?”

“Ha ha,” I said. Gesturing at the money, I explained, “I robbed a bank.”

“Ha ha,” the waiter said, and went away.

I looked at Edgarson. “I did rob a bank, you know. You’ve put me through a lot today.”

He’d had time to recover. Smiling in bemusement, shaking his head, he said, “You sure are an interesting fella to watch. I’ll say that for you.”

“Don’t bore me with your shoptalk.” I tossed over a small envelope from my publisher’s bank, where I’d cashed his advance check. “There’s fifteen hundred. You can count it, if you want.”

“I might as well,” he said, and proceeded to do so.

I kept dragging out my other money, most of it in twenties and tens with a few fifties sprinkled here and there. The eight-sixty from various pawnshops, the six hundred from the bad checks, the four-fifty from the nostalgia shops, the two seventy-five from the checking account. And another envelope; tossing it to him, I said, “My former savings account. Two thousand seven hundred sixty-three dollars and eighty cents.”

“It’s an amazing thing,” he said, placidly counting, “but most everybody’s worth more than they realize.”

“Fascinating,” I said, and pushed across the pyramid of loose bills. “Here’s another twenty-one eighty-five.”

The waiter, returning, placed my drink where my money had been and said, “How does a person get to be your friend?”

I picked up the drink. “Put this on his bill,” I said.

“I should think so,” the waiter said, and left.

I sipped and Edgarson counted. Then I sipped some more and Edgarson counted some more. Then I sipped some more and Edgarson said, “I make that six thousand four hundred and forty-eight dollars so far.” The bills, upon being counted, had disappeared into his clothing, and now he shoved my eight cents back across the table to me, saying, “We don’t mess with change. But we would like to see some more green-backs.”

“Out of my green sack,” I said, delving down inside my shirt and bringing out the swag. Propping the sack like a dildo in my lap, I loosened the drawstrings and started pulling out more cash.

This time I also did some counting, since I hadn’t had a chance yet to find out how much I’d made from my first excursion into major crime. Sorry, second excursion; I was forgetting Laura. “Two hundred,” I said, and flipped a stack of twenties across the table. “One eighty,” and a stack of tens. And so on and so on and so on.

And yet the bottom of the sack was reached too soon. I’d needed thirty-six hundred dollars, but my total profit from the bank job was only two thousand, seven hundred eighty.

Edgarson noticed it, too. “Nine thousand, two hundred and twenty-eight dollars,” he said at last. “I make you seven hundred and seventy-two dollars short.”