Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Kamera Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

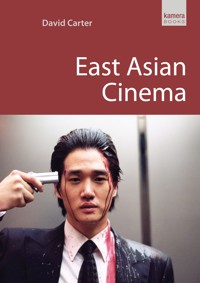

Film directors from East Asia frequently win top prizes at international film festivals, but in the West little is known about them nor about the cultures that produced them. It is not all martial arts, flying warriors, historical pageants and tea ceremonies. China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and North and South Korea went through periods of great political turmoil and rapid modernisation in the 20th century. The films of these countries reflect these changes and the conflicts between modern lifestyles and traditional values. In some cases it is capitalism versus communism, in others materialism versus spiritual concerns. This book provides an ideal reference work on all the major directors, with details of their films and checklists for the films of each country, useful for both ardent fan and serious student alike. It explores the common cultural heritage of the countries and their mutual influence. The films of China, Japan and Korea, for example, reflect their shared Buddhist and Confucian heritage. The films of China and North Korea are conditioned by Communist ideology. Early Korean cinema was dominated by the effects of Japanese colonial domination, and the Japanese cinema greatly influenced that of Taiwan.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 330

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

David Carter

EAST ASIAN CINEMA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A great debt is owed to the many scholars whose research inspired and informed me during the writing of this book. Some of the works which proved most rewarding are included in the section on Reference Materials. I also wish to record my special debt to Mr. Kim Chan Young, who helped me access many resources through his knowledge of the Korean, Japanese and Chinese languages. Finally thanks are also due to Hannah Patterson for her scrupulous editing.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

1 Introduction

2 The People’s Republic of China

Cinema in China: A Little History

Selected Directors and Films (China)

3 Hong Kong

Cinema in Hong Kong: A Little History

Selected Directors and Films (Hong Kong)

4 Taiwan

Cinema in Taiwan: A Little History

Selected Directors and Films (Taiwan)

5 Japan

Cinema in Japan: A Little History

Selected Directors and Films (Japan)

6 Korea

Cinema in South and North Korea: A Little History

Selected Directors and Films (South Korea)

Selected Films (North Korea)

7 Reference Materials

By the Same Author

Copyright

Plates

INTRODUCTION

There has been a rapid surge in international recognition of the films of the East Asian region in recent years. This is partly due to their being more readily available on video and DVD, but also because the films are increasingly winning top prizes at highly respected film festivals throughout the world. Some directors have acquired celebrity status, such as Ang Lee, Wong Kar Wai and Kim Ki-duk. The ultimate accolade has been the provision of resources, sometimes outside their native countries, to make big, glossy, Hollywood-style films, occasionally at a loss to the cultures that originally produced them.

Although one thinks of the cultures in question as disparate, they also have many features in common, which enables them to be classed loosely as East Asian. For the purposes of this book East Asia incorporates the countries of The People’s Republic of China (Mainland China), Hong Kong (now part of China but long a separate entity), Taiwan, Japan and the two Koreas (North and South). These countries share much common cultural heritage, in various proportions: that of Buddhism, Confucianism and in two cases Communism. They have also interacted with each other politically in various ways during the course of their histories. It is therefore meaningful to study the films of the region in relation to each other.

Many films of all the countries in the region reflect their shared Buddhist and Confucian heritage, and those of Mainland China and North Korea are conditioned by Communist ideology. In the works of some of the greatest directors it is also possible to trace the influence of traditional conventions in the visual arts which are uniquely East Asian: the imagery, the composition within the frame, and the sense of space (when to fill it, when to leave it empty). Forms of martial arts have also contributed greatly to the success of the films, from the most popular entertainment products to the most accomplished artistic achievements. Each country has been able to popularise its own unique forms of martial arts through its films: kung fu and tai chi in the Chinese-speaking areas, kendo and karate in Japan, and taekwondo and taekgyeon in Korea (mainly in the South).

As the cinemas of South and North Korea have common beginnings and share a common history until after World War II, the historical account in this book is presented as a continuous narrative divided into three parts: the period under Japanese domination, South Korea and North Korea. In the case of Taiwan, as the country was a new state set up by refugees from Mainland China and there had been only a little film production on the island during Japanese domination, it has been possible to depict its cinema history separately from that of the Mainland.

This book attempts to provide a broad overview of developments in the cinema in East Asia from the beginnings to the present day. With such a broad scope it has not been possible to describe all the films in depth; some directors alone have made over a hundred films. It is intended that the brief introductions provided to selected directors and their films will stimulate interest in the reader to explore further the full range of his or her output. In the final analysis all the films included in the present study are the author’s own personal choice. Some well-known films, including the readers’ favourites, will inevitably be absent. But the author’s selection has been well-considered, and films have only been included if they meet one or more specific criteria: they are historically significant, artistically accomplished, innovative, good examples of a genre, in some way unique, represent a trend, reflect a social or cultural theme in their countries of origin, or represent major landmarks in a director’s career. Some directors are not included, either because they do not meet any of these criteria or simply for lack of space.

CONVENTIONS IN THE TEXT

In the historical surveys of the film industries of each country, films are cited using the most commonly known English versions of their titles. When deemed useful the original language title is sometimes added in transliteration. This occurs particularly if the film might be otherwise difficult to track down or if it is not included in the lists of selected directors and films. Sometimes the original language title in transliteration is used alone, if no English language version is commonly used. All directors’ and actors’ names follow the word order common to all the major languages of the region: family name first followed by given names (e.g. Kurosawa Akira). In the body of the text, directors and actors who have adopted western-style second names, however, are cited according to the normal western convention, with the family name second (e.g. Jackie Chan). A different convention has been adopted, for ease of reference, in the sections containing lists of selected directors and films and in the index, as explained in the relevant paragraphs below. English transliteration follows the currently accepted system in each country, except when a director’s name has been internationally recognised under a different or former mode of spelling. The transliteration of the Japanese language has long been standardised, but in South Korea transliteration has undergone three different general modifications in the last two decades and North Korean transliterations do not always correspond to those in the South. It should be noted that with Korean ‘Lee’ and ‘Yi’ are alternative renderings of the same name, as are ‘Park’ and ‘Pak’, ‘Pae’ and ‘Bae’, etc. A useful tip when tracking names in bibliographies is to say them aloud and check those which sound similar, even if the spelling is different. With the Chinese language the situation is more complex, with conventions being different between the Mainland and Taiwan, and between the Mainland and Hong Kong before the take-over. Conventions also differ for representing the Mandarin and Cantonese dialects. It is impossible to include all alternatives within the scope of this book. The problem has been further complicated by the fact that many directors moved from one country to the other for either personal or political reasons, and the transliterations of their names often changed accordingly. I have endeavoured to keep things as simple as possible. Chinese directors and the titles of Chinese films are thus spelt in the transliterated forms by which they are most widely known. For more detailed information on the varieties of transliterated forms readers are advised to consult the relevant works in the section on Reference Materials. The abbreviation ‘q.v.’ (quod vide) is used on occasions to advise the reader to seek further information on the topic in other sections of the book by consulting the index.

LISTS OF SELECTED DIRECTORS AND THEIR FILMS

It has not been possible within the scope of the present book to cite cast and crew for all the films included. Generally each list includes first the following information: the directors’ names in alphabetical order by family name. In the case of directors who have adopted western-style second names, they are also listed by family name first, with the adopted name second and separated by a comma, to indicate the normal order (e.g. ‘Jackie Chan’ becomes ‘Chan, Jackie’). The same convention has been used in the index. There are indications of dates of birth and death, where known, together with place of birth and death where significant (i.e. in the case of certain Chinese directors). In the case of some directors, mainly Chinese, alternative forms of the names are provided if these are in common use. This is followed by information on the number of films directed, written, acted in and produced, together with a biographical note, but only when such information is available and deemed to be of interest. The selected films are then listed in chronological order under the most common English version of the title, together with a transliterated version of the original language title, and the date of the film’s first release. There is also an indication of the original language only when it is necessary to distinguish dialects (as in the case of many Chinese films made in Hong Kong). There then follows a summary of the plot. Under the heading ‘Comments’ are included any critical reflections and also any references to important actors, writers, cinematographers, and so on. Where insufficient information on plots is available, and no enlightening comments can be made, these headings are omitted. The film is still cited however to indicate that it is important in the director’s oeuvre. In the case of North Korea a different approach has had to be adopted, because until the late 1970s many films were acknowledged only as group productions, with no directors cited. Also it is difficult to obtain further information concerning many North Korean films. They have all, therefore, been listed by year of production. It should finally be stressed that many directors and films are cited in the historical surveys but not included in the lists of selected directors and their films.

REFERENCE MATERIALS AND INDEX

The works and Internet resources included in the section of Reference Materials are only a small number of those available. They have been included because they have proved useful to the author, and because they provide further reference material for readers who wish to explore the films of a particular country in more detail. The index includes only directors’ and actors’ names, by family name, the common English language titles of films, and a few commonly used concepts and genre names. As with the lists of selected directors and films, directors and actors who have adopted western-style second names are also listed by family name, with the adopted name placed second and separated from it by a comma, to indicate that it usually comes before the family name (e.g. ‘Jackie Chan’ becomes ‘Chan, Jackie’).

THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

CINEMA IN CHINA: A LITTLE HISTORY

In 1895 China signed the first of a series of treaties which led to its division between several foreign powers. It is against this historical background that one must view the first recorded screening of a film in China: on August 11, 1896, when a foreign projectionist showed a film by the Lumière brothers, only a year after they had patented their ‘cinématographe’ machine. It was shown as part of a variety performance. With the suppression of the Boxer rebellion against foreign influence in 1900 by the combined forces of Britain, the USA, France, Japan and Russia, the Qing dynasty was in rapid decline, with many secret societies set up by disaffected Chinese, both at home and abroad, working to hasten its demise. This did not deter Liu Zhushan from bringing a projector and films to Beijing in 1903 and essentially inaugurating China’s film industry. In the year 1905, when the traditional Confucian examination system that governed access to the imperial government was being dismantled, the first truly Chinese film was made by the Feng Tai Photography Shop. In November of that year they filmed a performance of Dingjun Mountain by the Beijing Opera. For the next decade the film production companies were foreign-owned, and the focus of the new industry was clearly shifting to Shanghai.

SHANGHAI AS CENTRE

After the Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911 by revolution it took a few years for the domestic film industry to be set up in earnest. The first independent Chinese screenplay, The Difficult Couple, was filmed in Shanghai in 1913, directed by Zheng Zhengqiu and Zhang Shichuan. It then became difficult to obtain supplies of film stock because of the advent of the First World War. When stocks became available again Zhang Shichuan set up the first Chinese-owned film production company in Shanghai in 1916. In the 1920s the technical crews in Shanghai were very much trained by technicians from America, and American influence continued throughout the 20s and 30s. The first truly successful home-grown Chinese feature-length film was Yan Ruisheng, which was released in 1921, the year the Chinese Communist party was established, and it immediately spawned imitations. In 1923 the Nationalists under Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek established links with the Soviet Communist International (the Comintern), hoping, amongst other things, to gain help in warding off Japanese expansionism. After Sun Yat-sen’s death in 1925, there was a power struggle in the Nationalist Party (the Kuomintang, or KMT), with Chiang Kai-shek favouring a capitalist military dictatorship. During this period the film industry was mainly dominated by martial arts films and romantic dramas. Almost none of these films have survived. From 1926 on, Chiang attempted to put an end to the growing Communist influence, and in 1927 his troops massacred about 5,000 Communists in Shanghai, with the help of the backing of Shanghai bankers, foreigners and armed gangsters. By the middle of 1928 he had established a national government in Beijing, but only dominated about half the country, the rest of which was run by local warlords. After the massacre of 1927 the Communists eventually came to support the views of Mao Zedong who advocated rural-based revolt. In 1929 the Kuomintang decided to crack down on the film industry and introduced censorship. By 1930 the Communists had managed to build up an army of about 40,000 men, and Chiang’s attempts to exterminate them failed. The Communists continued to expand their territory. This doubtless gave encouragement to many left-wing minded workers in the film industry. In 1930 Luo Mingyou set up the Linhua Company, which became a centre for leftist film production, less committed to commercial success than provoking thought. The year 1931, when Japan annexed Manchuria, yielded several landmarks in the Chinese cinema: a league of left-wing dramatists was established, including several filmmakers who had connections with the Communist party; the Mingxing Company produced the first sound film, Singsong Girl Red Peony, and the first feature film was made using film stock produced entirely in China. When the Japanese bombed Shanghai in 1932, on the pretext of countering Communist demonstrations, the Communists declared war on them but the Kuomintang sought appeasement. The bombing disrupted film production for some time in Shanghai. With the Japanese attempting to extend their territorial control in the north in 1933, more films began to appear with leftist slants, notably Cheng Bugao’s Spring Silkworms. With Chiang’s fifth campaign of large-scale extermination, which began in October of that year, the Communists started to suffer some heavy losses, and by October 1934 they were facing possible defeat. At this juncture Mao decided to march north to a Communist stronghold in Shaanxi. There was in fact not one ‘Long March’ but several that year, with various Communist armies in the south making their way to Shaanxi. Major films produced in this period with a left-wing message were Sun-yu’s Big Road, Wu Yonggang’s The Goddess, and Cai Chusheng’s Song of the Fishermen. The latter film was the first to win an international award for China at the Moscow Film Festival in 1935. Due to the emergence of several talented directors at this time it is often referred to as the first ‘Golden Period’ of Chinese cinema. The first true film stars in the Chinese cinema also appeared in the same decade, such as Hu Die, Zhou Zuan, Jin Yan and Ruan Lingyu. Two other major films in this period were Street Angel and Crossroads (both released in 1937). In 1936 the Communists and the Kuomintang had formed an anti-Japanese alliance, but this did little to halt the Japanese who, in 1937, launched an all-out invasion of China, taking over Shanghai and culminating at the end of the year in the infamous Nanjing Massacre, still a bitter memory for all Chinese. The Chinese film industry was dispersed, and all production companies except Xinhua closed down, with some members following the Kuomintang in their retreat eastward to Chongqing, others fleeing to Hong Kong, and some joining the Communists in Yan’an. A few actually stayed in Shanghai in the ‘safe haven’ of the foreign concessions, and there were a number who agreed to work with the Japanese. When the Second World War began in Europe in 1939, the Japanese set up their own film industry in Manchuria and took over the Shanghai film industry. They produced films for both their own soldiers and for the local Chinese population. The Communist army also obtained its first 35mm camera and started to make its own documentaries. During the war, in 1942, Mao laid down his prescription for a truly Communist art, in ‘Talks on Literature and Art at the Yan’an Forum’, emphasising the necessity of subordinating art to political ideals. This was to become the guiding principle in film production with the advent of the People’s Republic.

THE SECOND GOLDEN AGE

When the war against Japan ended in 1945, civil war broke out in China between the Communists and the Kuomintang. In 1946 progressive filmmakers were now able to return to Shanghai, taking over Lianhua again. They were determined to resist the power of the Kuomintang, and set up the new Kunlun studio as their base. Many of the films produced at that time revealed disillusionment with the dominance by Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalists, classic examples being Myriads of Lights (1948), San Mao (1949) and Crows and Sparrows (1949). When the Russians retreated from Manchuria in 1947, the Communists took over control of the area and set up the Northeast Film Studio at Xingshan. In the same year a famous war epic, A Spring River Flows East, was produced in Shanghai, directed by Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli. This is a three-hour-long film in two parts, depicting the problems of ordinary Chinese people during the war with Japan. Audiences were able to identify with the social and political issues in the film, and it became very popular. Another important production company formed by left-wing filmmakers in Shanghai was the Wenhua Film Company, which was responsible for several recognized masterpieces. Particularly famous is Springtime in a Small Town (1948), directed by Fei Mu. There was a remake in 2002 by the Fifth Generation Chinese director Tian ZhuangZhuang.

By 1948 the Communists had recruited so many Kuomintang soldiers that they equalled them in both numbers and supplies, and after the Kuomintang had been defeated in three battles, hundreds of thousands of their soldiers defected to the Communists. On 1 October 1949, in Beijing, Mao Zedong proclaimed the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, and Chiang Kai-shek fled to what was then still known internationally as the island of Formosa (later Taiwan). He took the entire gold reserves of the country and what remained of the air force and navy. There were altogether about two million refugees on the island. To ensure its security and prevent an attack by the mainland forces, President Truman ordered a US naval blockade of the island. With the establishment of the People’s Republic, the Northeast Film Studio moved to Changchun and started to make its first feature film, Bridge, and a film industry was set up on Taiwan, based around some documentary filmmakers who retreated there from the mainland. After the establishment of the People’s Republic, the government regarded film as an important art form for the masses and as a means of propaganda. In 1950 any American films remaining in China were withdrawn from circulation, and there was a crackdown against counter-revolutionaries in 1951. Based on the Soviet model, the government set up the first Five Year Plan in 1953, which was generally successful in raising production in most areas of industry. It also nationalised the film industry and took steps to extend film distribution beyond the major cities, using mobile projection teams.

Writers, artists and filmmakers were subject to strict ideological control during this period, following the guidelines drawn up by Mao in the Yan’an manifesto. In response to the easing of some controls during the early years of the Five Year Plan, the writer Hu Feng criticised the use of Marxist values in judging creative work. He was accused of being employed by the Kuomintang, and a nationwide witchhunt began for similar writers. Mao and some other influential figures felt, however, that party control had been successful enough to allow some critical voices to surface. He famously proposed ‘letting a hundred flowers bloom’ in the arts and ‘a hundred schools of thought contend’ in the sciences. His ideas were officially recognised in the spring of 1957. This so-called ‘Hundred Flowers Campaign’ led to some liberalisation in literature and the arts and, in the film industry, to the production of satirical comedies and the publication of articles, which openly criticised some previous films for failing to have popular appeal. Many writers took advantage of the new freedoms to criticise the Communist monopoly and its abuses of power. The Communist party soon realised that some restraint was urgently needed and a campaign against right-thinkers was launched. Within six months about 300,000 intellectuals had been identified as right-wing, dismissed from their jobs, and in many cases imprisoned and even sent to labour camps. In the film world satires were now banned and Communist orthodoxy prevailed.

THE GREAT LEAP FORWARD AND THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

There followed a period of disastrous economic experiments known as ‘The Great Leap Forward’, introduced by Mao. There were also calamitous droughts and floods, with an enormous ensuing famine, in which, at a conservative estimate, 30 million Chinese starved to death, and perhaps as many as 60 million. By the late 1950s relations with the Soviet Union were in decline. Mao did not approve of the USSR’s policy of peaceful coexistence with the USA, and the USSR went back on its promise to provide China with a prototype atomic bomb. In 1960 the Russians removed all their foreign experts working in China. In the arts the general anti-Soviet feeling led to a rejection of the so-called ‘Soviet Socialist Realism’ and in the cinema essentially more Chinese ideals were to be pursued: the ‘combination of revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism’. Film production was enormously increased, but the resulting products were mainly rather crude revolutionary documentaries. In some of the more subtle films the pure, ideal proletarian hero was replaced by more ambiguous central characters.

Mao had been losing influence and power within the party, and in 1966 he launched what was in effect another kind of ‘Great Leap Forward’. Again he wanted to create new socialist structures overnight. It became known as ‘The Cultural Revolution’. He also started a personality cult around himself, with the aid of Lin Biao, the Minister of Defence and head of the People’s Liberation Army, who had also published the collection of Mao’s sayings known as ‘The Little Red Book’. With the aid of his wife Jiang Qing, a former Shanghai B-grade film star, Mao launched a purge of the arts. The production of feature films stopped altogether, and Jiang Qing, the ex-starlet, used the opportunity to settle a lot of old scores. Many important figures in the film industry were sent to work in the countryside or imprisoned, and many died or committed suicide.

Some measure of political stability was restored by 1968 through the interventions of the People’s Liberation Army, but only after it conducted its own reign of terror. By 1970 the production of feature films was at least able to start up again, but they were mainly recordings of stage productions of Jiang Qing’s model revolutionary operas, notably TakingTiger Mountain By Strategy (1970). Another notable film from this period is the ballet version of the revolutionary opera The Red Detachment ofWomen (1970).

In 1973 Chinese politics remained very factional. There were the moderates, with Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, recently restored to influence, and on the other side the radical Maoists, led by Jiang Qing. Although it was under strict censorship at this time, the regular production of feature films started again. One such film of the period was Bright Sunny Skies.

By 1976 several significant members of the old guard had died, Zhou Enlai in January and Mao in September, and Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng had Jiang Qing’s ‘Gang of Four’ arrested in October. Film production fell for a while but was soon able to return to a level comparable to that before the Cultural Revolution. By the middle of 1977 Deng Xiaoping had come to power and was appointed vice-premier, vice-chairman of the Party and Chief of Staff of the People’s Liberation Army. In 1978 the famous Democracy Wall was set up, enabling some measure at least of expression of opinion. Some criticism of the Cultural Revolution was now possible in films. The Beijing Film Academy reopened and took on a whole new class of directors, later to be known as the ‘Fifth Generation’.

THE FIFTH GENERATION

In 1979, after rehabilitating some important people from the period before the Cultural Revolution, the Communist Party decided that there was a limit to the extent of freedom of speech they could allow and closed down the Democracy Wall in December. At this time the film industry started to make more innovative films, using techniques such as zooms and flashbacks which had been rare in Chinese films. Notable in this respect are the films Troubled Laughter (1979) and Xiao Hua (1980). In 1980 Hua Guofeng was replaced by Zhao Ziyang who had won favour for carrying through effective economic reforms in Sichuan. A notable film which appeared in this year was The Legend of TianyunMountain, which criticised the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1958. In 1981 the film Bitter Love, which provided negative criticism not only about the past but also about present conditions, was banned. 1982 marks a significant development, for it was in that year that the so-called ‘Fifth Generation’ of filmmakers graduated from the Beijing Film Academy. These were basically the first new generation of filmmakers to produce films since the Cultural Revolution and they made a conscious decision to reject traditional methods of storytelling, opting instead for freer, more liberal approaches.

In 1983 the government started a campaign against what they called ‘spiritual pollution’, and under this policy any films containing too much violence or vulgar behaviour were banned. The Xian Film Studio came to prominence at this time, with its director, Wu Tianming, pursuing a policy of subsidising new experimental films through income from deliberately commercial films. Many of the ‘Fifth Generation’ filmmakers thrived there, and the success of the enterprise made Xian a successful rival to the Shanghai Film Studio.

With Deng Xiao Ping at the helm China now began to make significant economic progress. The so-called ‘Responsibility System’ introduced into rural areas in 1984 allowed agricultural households and factories to sell any goods in excess of quota on the open market. And in coastal areas special economic areas were set up, most notably at Zhuhai, near Macau, Shenzhen, near Hong Kong, and at Shantou and Xiamen, close to the Taiwan Strait. Economic growth was soon to rise dramatically. In this same year the first of the ‘Fifth Generation’ films was produced, One and Eight, but it was banned from being exported. In the following year however a film was released that, though ignored within China, was to attain great success internationally. This was Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth. In 1988 the film Red Sorghum, directed by Zhang Yimou, was not only the first ‘Fifth Generation’ film to be successful in China, but it also won the Golden Bear award at the Berlin Film Festival.

The films of the ‘Fifth Generation’ are generally very diverse in style, ranging from black comedy (such as The Black Cannon Incident, 1985, directed by Huang Jianxin) to the very esoteric (Life on a String, by Chen Kaige, released in 1991). Among other notable directors commonly identified as members of the ‘Fifth Generation’ are Hu Mei, Zhou Xiaowen and Wu Ziniu. As a home-based group the ‘Fifth Generation’ directors ceased to exist after the infamous Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989. Chen Kaige and Wu Tianming were in the USA at the time and decided to remain abroad. Huang Jianxin went to Australia. Many other directors gave up cinema work and moved into television production. One of the crowning achievements of the ‘Fifth Generation’ also occurred in 1989 however, when Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s film City of Sadness won the Golden Lion at Venice. Hou (known in Mainland China as Hou Xiaoxian) had moved to Taiwan in 1948 and became a major director there. Selected films by him are therefore listed under that country.

It must be mentioned that directors from the previous generation, what might be termed the ‘Fourth Generation’, had still continued to be productive during the rise of the ‘Fifth Generation’. Their careers had been disrupted by the Cultural Revolution, but many of them, especially Wu Tianming, helped the Xian Film Studio enormously by supporting ‘Fifth Generation’ directors financially.

THE SIXTH GENERATION

In the 1990s a phenomenon arose known as the ‘Sixth Generation’ of filmmakers. These divisions into generations refer to the number of generations since the 1949 revolution. With continuing state censorship, a kind of underground film movement developed, with the films made quickly and cheaply, using hand-held cameras and long takes. The mode of filming gives them a documentary feel. Many of them were joint ventures and in some cases they were made with the aid of foreign investment. The films are individualistic and well worth tracking down for their reflections on contemporary city life. Important directors associated with this trend are Zhang Yuan (East Palace West Palace and Beijing Bastards), Lou Ye (Suzhou River), Jia Zhangke (UnknownPleasures, Xiao Wu, Platform and The World), and Wang Xiaoshuai (TheDays and Beijing Bicycle).

THE NEW DOCUMENTARY MOVEMENT

With the growth of commercialisation complex social changes have taken place in China, many of which have been reflected in the films of the New Documentary Movement. The first significant film of this trend was the film Bumming in Beijing by Wu Wenguang. An amazing and rather exhausting example of the genre is Wang Bing’s nine-hour-long study of de-industrialisation called Tie Xi Qu (meaning ‘West of the Tracks’), all three parts of it released in 2003. A leading woman director in the movement, Li Hong, made a film called Out of Pheonix Bridge (1997), about four young women who move from rural areas to the big cities to try to earn more money, as many millions of both men and women have done. Many of these films are rather heavy going but they do reveal fascinating insights into the lives of Chinese workers.

THE NEW CHINESE INTERNATIONAL CINEMA

One particular film has done more than many to attract an international audience to Chinese films, helping to increase the popularity of other films which might have otherwise have remained little known to Westerners. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), directed by the Taiwanese Lee Ang (known internationally as Ang Lee), was enormously successful at the box-office in Western countries, although it must be said that perhaps the director was pandering too much to Western taste. The international nature of the film is symptomatic of a trend, which makes it increasingly difficult to distinguish a film as being from one specific Chinese-speaking community. In the case of Crouching Tiger,Hidden Dragon, for example, the director was Taiwanese, but the leading actors and actresses were from not only Taiwan but also Hong Kong, and Mainland China, and the funding from an array of countries.

In 2002 an attempt was made to make another Chinese film which might equal or even exceed the success of Crouching Tiger, HiddenDragon:Hero, directed by Zhang Yimou. The cast and crew were again multinational, and it featured many actors and actresses, who were already well known in the West. It was an enormous success, both throughout Asia and in the West, and was the most popular film in the USA for two weeks. Income from the film in the USA alone was enough to cover all production costs.

SELECTED DIRECTORS AND FILMS (CHINA)

As explained in the introduction, there are considerable problems in allo-cating precise provenance to some Chinese directors. There are many who started their careers in Mainland China, and then later continued to be productive in Taiwan or Hong Kong, in the latter case becoming citizens of The People’s Republic after the British handed over power in 1997. Where information about any major geographical moves in a director’s career is known it will be noted if significant. For information on the sequence of family and personal names and conventions of transliteration please see the Introduction.

CAI CHUSHENG

b. 1906, China; d. 1968.

As director: 15 films. As writer: 2 films. As producer: 1 film.

Biographical note: One of the most prolific and successful directors in the 1930s and 1940s, he spent the Second World War in Hong Kong, where he worked with the director Situ Huimin. After the war he returned to Shanghai and helped to set up the anti-Nationalist Kunlun Film Studio. In 1947 he co-directed with Zheng Junli the epic The SpringRiver Flows East. After the Liberation in 1949 he helped in the reorganisation of the film industry, but did not work as a director any more, except on one film, Zhujiang Lei, in 1950. He died as a victim of the Cultural Revolution in 1968.

Song of the Fishermen (Yuguang Qu), 1935.

Comments: This was the first Chinese film to win a major international prize, at the Moscow Film Festival in 1935.

The Spring River Flows East (Yi Jiang Chun Shui Xiang Dong Liu), 1947.

Plot: The story of a poor family during the period of the Japanese invasion of China in the 1930s. One son, Zhongliang, leaves his wife and young son to join a medical group which supports the Chinese army. They do not see each other again for eight years. The other son, Zhangmin, decides to hide from the Japanese and protect his family. Zhongliang is very successful working in a company and starts to lead a life of luxury. His life is contrasted with the wretched existence of his wife and child.

Comments: The film was co-directed and co-written with Zheng Junli. It is three hours long and in two parts. It was very popular at the time of its first release. Ordinary Chinese people found that they could identify closely with the family in the film and their problems during the war with the Japanese. The film provides a moving evocation of the issues of the period.

CHEN KAIGE

b. 1952, China.

As director: 12 films (approx. by 2005). As writer: 6 films. As actor: 3 films. As producer: 2 films.

Biographical note: He was born into a film family, his father a director of Chinese opera films and his mother a script editor. During the Cultural Revolution he was sent with a group of schoolmates to work on a rubber plantation in Yunnan Province. Five years later he went back to Beijing, and after working in a factory for some time, studied at the Beijing Film Academy. He was helped in his career by Zhang Yimou (q.v.), who encouraged him to join the ‘Youth Film Group’ at the Guangxi Studio. With Zhang as cinematographer he established his reputation with the film Yellow Earth, in 1984. Other early films worth noting are Big Parade, released in 1987, and King of the Children, (1987), drawing on his experiences in Yunnan Province. In 1988 he took up a fellowship at New York University, where he stayed till 1989, making music videos along the way. One of the films which made him more widely known internationally is undoubtedly Farewell My Concubine (1993).

Yellow Earth (Huang Tu Di), 1984.

Plot: An adaptation of a novel by Ge Lan and tells the story of a visit by a soldier, Gu Qing, who has the job of making records of local folk songs for posterity. He gradually learns that the happy, celebratory songs he was sent to collect do not actually exist. Instead they are all about hardship and suffering. He becomes acquainted with his host’s daughter, Cuiqiao, who is tempted by his stories of female liberation under communism to flee her home and her forced betrothal to an older man. Tragedy however ensues.

Comments: Renowned for its combination of minimal dialogue and action, and stunning visual images, it provides a disturbing exploration of the discrepancies between idealistic views of rural culture and the bitter realities. Its images haunt the viewer long after watching the film.

Big Parade (Da Yue Bing), 1986.

Plot: The film depicts an airforce unit preparing to participate in the parade on National Day, 1985, in Tiananmen Square.

Comments: A fascinating study of the personal relations between members of the unit.

King of the Children (Hai ZiWang), 1987.

Plot: Set in the Cultural Revolution, the film tells of the first appointment of a young teacher, Lao Gan, to a small village. The title is an idiomatic phrase for a teacher in the local dialect. At first he follows the lesson plans laid down by the central directorate, which involve the repetitive copying of political slogans. The brightest pupil, Wang Fu, accuses him of not knowing how to teach, and he changes his methods, taking them out into the natural world. He inevitably incurs the anger of the authorities.

Comments: Rather tedious in it exposition of educational philosophy, it nevertheless provides profound reflections on how children become part of their national culture and how their personalities develop.

Life on a String (Bian Zou Bian Chang), 1991.

Plot: A blind old itinerant musician, regarded as a saint, was told by his own master years ago that when he broke the 1,000th string on his instrument, he would be able to see. His apprentice, also blind, has more earthly aims, longing for the love of a village girl he adores. These twin elements of suspense sustain the film.

Comments: A very philosophical film, occasioning much reflection on vision and blindness, silence and music, life and death, it is set among stunning landscapes in Western China. It is a thought-provoking and visually memorable film.

Farewell My Concubine (Ba Wang Bie Ji), 1993.

Plot: Cheng Dieyi (Leslie Cheung) and Duan Xiaolou (Zhang Fengyi) are two opera performers, who have been friends since childhood. Cheng is the smaller and more delicate physically and plays the female roles. In a famous opera called Farewell My Concubine, Duan plays the king and Cheng the concubine. Cheng suppresses his love for Duan, but when Duan meets and marries a prostitute, Cheng becomes wildly jealous. Their partnership is split and they are drawn into the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Years later they attempt to stage a reunion performance of their most famous work, but Cheng’s consuming passion brings about a tragic ending.

Comments: The film traces the personal relationship of the two men against the backdrop of the main events in twentieth-century Chinese history. It interweaves the personal story with historic events very convincingly and evokes powerfully the beauties of traditional Chinese opera.

The Promise (Wu Ji), 2005.

Plot: