Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Two Rivers Press

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

Edith Morley (1875-1964) was a scholar and the main 20th century editor of the works of Henry Crabb Robinson. She was the first woman appointed to a chair at an English university-level institution. Born into a middle-class Victorian family, she hated being a girl, but a forward-thinking home life and a good education enabled her to overcome prejudices and become Professor of English Language at University College, Reading, in 1908. An early feminist with a strong social conscience, she 'fought… with courage… and passionate sincerity for human rights and freedom.' Covering the vividly described era of her late Victorian childhood, her student days with the increasing freedoms they brought, the early feminist movement, the growing pains of a new university and, much later, the traumas endured by refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, this absorbing memoir brings alive a very different era, one foundational to the freedoms we enjoy today. Intended to 'relate my experiences to the background of my period and to portray incidents in the life of a woman born in the last quarter of the nineteenth century', Edith Morley's 1944 memoir, Before and After, was written a few years after her retirement.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 312

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Before and After

Born in Bayswater in 1875, Edith Morley ‘did hate being a girl’, though she found the middle-class conventions of the day restrictive rather than repressive and benefited from a good education, thanks to her surgeon-dentist father and well-read mother. She obtained an ‘equivalent’ degree from Oxford University (the only type available to the few female students at the time) and was appointed Professor of English Language at University College, Reading, in 1908, becoming the first female professor in the United Kingdom. She is best known as the primary twentieth-century editor of Henry Crabb Robinson’s writings (the author of a comprehensive biography) and for her Women Workers in Seven Professions: A Survey of their Economic Conditions and Prospects (1914), published while she was a member of the Fabian Executive Committee. Before and After, written after her retirement in 1940, was ‘intended to relate my experiences to the background of my period and to portray incidents in the life of a woman born in the last quarter of the nineteenth century’. She was awarded an OBE in 1950 for her work in setting up the Reading Refugee Committee and assisting Jewish refugees in World War II. She died in 1964.

Also published by Two Rivers Press:

Silchester: Life on the dig by Jenny Halstead & Michael Fulford

The Writing on the Wall: Reading’s Latin inscriptions by Peter Kruschwitz

Caught on Camera: Reading in the 70s by Terry Allsop

Plant Portraits by Post: Post & Go British Flora by Julia Trickey

Allen W. Seaby: Art and Nature by Martin Andrews & Robert Gillmor

Reading Detectives by Kerry Renshaw

Fox Talbot & the Reading Establishment by Martin Andrews

Cover Birds by Robert Gillmor

All Change at Reading: The Railway and the Station1840–2013 by Adam Sowan

An Artist’s Year in the Harris Garden by Jenny Halstead

Caversham Court Gardens: A Heritage Guide by Friends of Caversham Court Gardens

Believing in Reading: Our Places of Worship by Adam Sowan

Newtown: A Photographic Journey in Reading 1974 by Terry Allsop

Bikes, Balls & Biscuitmen: Our Sporting Life by Tim Crooks & Reading Museum

Birds, Blocks & Stamps: Post & Go Birds of Britain by Robert Gillmor

The Reading Quiz Book by Adam Sowan

Bizarre Berkshire: An A–Z Guide by Duncan Mackay

Broad Street Chapel & the Origins of Dissent in Reading by Geoff Sawers

Reading Poetry: An Anthology edited by Peter Robinson

Reading: A Horse-Racing Town by Nigel Sutcliffe

Eat Wild by Duncan MacKay

Down by the River: The Thames and Kennet in Reading by Gillian Clark

A Much-maligned Town: Opinions of Reading 1126–2008 by Adam Sowan

A Mark of Affection: The Soane Obelisk in Reading by Adam Sowan

The Stranger in Reading edited by Adam Sowan

The Holy Brook by Adam Sowan

Charms against Jackals edited by Adam Stout and Geoff Sawers

Abattoirs Road to Zinzan Street by Adam Sowan

First published in the UK in 2016 by Two Rivers Press

7 Denmark Road, Reading RG1 5PA.

www.tworiverspress.com

Copyright © Two Rivers Press 2016

Copyright © in the original text and footnotes Estate of Edith Morley 2016

Copyright © in Foreword Mary Beard 2016

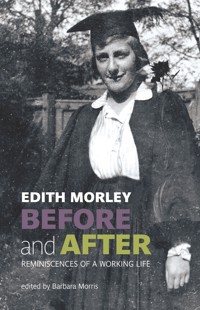

The original typescript of this memoir and the picture of Edith Morley on the front cover, as well as the one on the jacket flap of the hardback edition, are from the University of Reading Special Collections archive and reproduced with permission and gratitude.

The right of Edith Morley to be identified as the author of the work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-909747-16-6 (pb) | 978-1-909747-19-7 (hb)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Two Rivers Press is represented in the UK by Inpress Ltd and distributed by Central Books.

Cover and text design by Nadja Guggi

Typeset in Janson and Parisine

Ebook conversion by leeds-ebooks.co.uk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Ashford Colour Press, Gosport.

Acknowledgements

Two Rivers Press would like to thank the Friends of Reading University and the Reading University Women's Club for their financial support of this project. We are also grateful to the previous and current Heads of the Department of English Literature, in the School of Literature and Languages, for their help in coordinating the various sources of support for this project both inside and outside the University of Reading.

Before and After

Reminiscences of a working life

by Edith Morley

edited by Barbara Morris

I have been very glad to pay for the production and initial printings of this Edith Morley memoir as a donation to the English Literature Department of the University of Reading

in ever loving memory of my late wife,

Ann Patricia Palmer née Newton (1938–2011),

who was an undergraduate, leading to her BA degree, in that Department during 1956 to 1959, and whose consequential, continued enthusiasm for English literature was of great benefit to Ann, and to me as a scientist, throughout the forty-nine wonderful years of our marriage.

— Derek W. Palmer

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Preface

Chapter 1: Childhood background

Chapter 2: Home life

Chapter 3: External conditions

Chapter 4: Education and emancipation

Chapter 5: First years of professional work

Chapter 6: Other interests

Chapter 7: Reading, college and university

Chapter 8: Social and political activities

Chapter 9: The last chapter

Epilogue

Biographical notes

Foreword

Every woman now working in British universities – or in any other profession, for that matter – will recognise Edith Morley’s story, told in this wonderfully direct memoir. The first woman to be a ‘professor’ in the United Kingdom, she was as ‘awkward’, ‘difficult’ and ‘determined’ as any of her twenty-first century successors must be (and we are still described in the same way). Quite simply, she took on the establishment, as feminists have done ever since.

When the first professors at the new University College at Reading were designated in 1907, Morley was left off the list of those honoured. Her description of the controversy is instantly recognisable, even now. She thought that her achievements were not quite up to the honour of a chair; but when she realised that she was the only ‘lecturer in charge of a subject’ who was not to be made professor, she took a certain fire in her soul – and refused to stay in her post unless she was ‘promoted’.

It remains a credit to the new University at Reading that it broke convention and gave Morley a chair. It is perhaps even more of a credit to Morley herself that she stood up to those conventions and claimed the recognition due to her. She would no doubt be disheartened to discover that – more than a century later – her female successors in the academy are still sometimes struggling to win their due rewards.

Professor Mary Beard

January 2016

Introduction

The University of Reading reaches its 90th birthday in 2016, and the publication of Edith Morley’s memoir, Before and After, is part of the celebration, for Morley was involved at the start of the University’s life and provides a very personal account of its growth and teething troubles. The struggles she was engaged in to become the first female professor in the country were considerable and are no less relevant today, but she must have influenced opinion and practices in the University, because in 1933 women made up roughly one-fifth of the full-time academic staff in the three Faculties. When an enquiry came from the Vice-Chancellor at Liverpool about the situation when women married, Sibly, Reading’s Vice-Chancellor, simply indicated that there had been no problem or questions raised when five of the female staff got married: ‘Reading had come quite easily to accept matters of which other universities made very heavy weather indeed’.

Morley wrote her reminiscences after her retirement in 1940. The typescript exists in three copies in the Morley archive held in the University of Reading’s Special Collections. One of these copies has been heavily annotated with manuscript additions in her small but neat writing, and this copy has formed the present text.

In 1944 she sent it to the publishers Allen and Unwin who rejected it on the grounds that ‘those who don’t remember these things will have read of them often enough in novels of the period’ and that it was ‘for yesterday or tomorrow, but not today’. Given the wartime restrictions on paper, publishers were very limited in what they could take on, and they were probably right to refuse it. But ‘tomorrow’ is now, and a good time to make available this memoir. What was still familiar to potential readers in 1944 is now no longer so, and her descriptions of her life growing up in the last quarter of the nineteenth century are fascinating, while her account of the 1938 refugee crisis has many resonances for today.

She wrote the memoir partly to explain to young people what life was like for young women of her generation and class, and partly to chronicle her involvement in the issues of the time – more particularly, early feminist and socialist thinking and activities – and the people she met who were involved in them. She omits many aspects of her life: she was born into a Jewish family but never mentions religion or how it might have affected her growing up. And, perhaps more strangely, she mentions nothing of her major literary activity, the editing of the works of the prolific eighteenth-century diarist and journalist Henry Crabb Robinson.

Rejected by the publisher, her text was never edited, and had she been able to publish, I think she would have made many amendments. We have however been anxious to present her text as closely as possible to the one she wrote in 1944. Editing a posthumous work brings problems and responsibilities, as there is no possibility of consulting the author. We have shortened the title which in the original was ‘Looking before and after’. I have provided additional punctuation, and have made minimal orthographic changes in line with contemporary practice. Occasional sentences were convoluted and have been straightened out. Morley’s memory was not always reliable, and a few factual errors have been quietly corrected. Morley introduced several footnotes which are marked with * and †. In addition to her these, I have supplied, where possible, explanations of some of her more obscure references as numbered footnotes. Morley mentions very many people, some familiar, others less so, and the latter are also briefly described, singly or collectively, in the footnotes. For those people who most exemplify her main concerns – feminists, Fabians, academics, and people associated with Reading University – brief biographies are provided at the back of the book and set in small caps. The very famous require no comment.

What was she like as a person? Holt describes her thus: ‘She was provocative, disturbing, aggressive, and intransigent: others kept their distance to avoid collision and damage. … Yet she loved humanity… . She was ever ready to fight for the oppressed, especially if feminine’.* Her obituary in the local paper says, ‘She fought not only with courage but sometimes aggression and always with passionate sincerity for Human Rights and freedom’.†

The publication of these memoirs would not have been possible without the generous donation made by Derek Palmer, in memory of his late wife Ann, an undergraduate in the English Department in the late 1950s. I am also very grateful to the staff of the Special Collections Department, and to Professor Peter Robinson and Anke Ueberberg for their advice and support.

Barbara Morris

* J.C. Holt, The University of Reading: The first fifty years (Reading University Press, 1977)

†Reading Mercury, 23rd January 1964

To my former colleagues and students,

in gratitude

Preface

This book is not an autobiography. It is intended to relate my experiences to the background of my period and to portray incidents in the life of a woman born in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. My youth was passed in conditions not always realised by the young people of today. Later on my work and interests brought me into contact with various movements and persons of historic importance, and now the enforced leisure of advancing years gives me the opportunity to indulge in the reminiscent mood, which is the prerogative of age, and to set down some records of the past for the benefit of present-day readers.

Edith Morley

CHAPTER 1:

Childhood background

I was born in 1875, in the tall Bayswater house which was to be my home until my mother’s death in 1926. My father was a surgeon-dentist with a West End practice, and since he had six children, the eldest an invalid, there was never much money to spare for luxuries. On the other hand, since he was a great stickler for professional etiquette and the proprieties, we were brought up strictly in accordance with the middle-class conventions of the day, which included, happily, a beloved nurse and as good an education as could be managed for all of us, a six-weeks country or seaside holiday every summer and regular visits to the pantomime or theatre at Christmas or on birthdays. Certainly in my own home and in the houses we visited, nothing was known of the Victorian suppression and repression of children about which so much is read today. On the contrary, I was myself a much indulged and very spoiled little girl, very conscious of my importance as the only sister among four brothers, two much older, one near my own age, and one nine years younger. But I did hate being a girl* and can still remember my indignation at hearing my brother told that only girls cheated at games and the like, or cried when they were hurt. And how I hated and resented wearing gloves. When quite small I suffered from a thick woollen veil, which was supposed to safeguard the complexion, but my very noisy and voluble protests soon relieved me of that infliction – old-fashioned and unusual even in those days. I also resented and constantly disobeyed the rule that I must not slide down the banisters or turn head over heels! I had gymnastic lessons, however, and learned to swim, but I yearned for more of the team games which girls did not yet play and suffered a good deal from insufficient outlets for my physical exuberance. Walks in Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park were no adequate substitute, even when enlivened by forbidden tree climbing and jumping of railings, or by games of hide-and-seek.

My father wished me to be educated at home by a governess but luckily yielded to my desire to go to school. When I was just five, I was sent to a neighbouring kindergarten which was kept by a natural history enthusiast, to whose wise guidance my childhood owed an incalculable debt. ‘Brownie’ as we called her, became a family friend: she spent many holidays with us and even succeeded in persuading my nurse that muddied clothes didn’t matter if they were the results of dredging expeditions. From her, I learned to collect everything that crept and crawled: I kept silkworms, spiders (until they got loose in the drawing room), tadpoles and newts; I pressed and named flowers; looked for fossils, collected shells and joined a ‘Practical Naturalists’ Society’. And when my ‘museum’ – a glass case with sliding trays and bookshelves on the top of the cabinet – was supplemented by a real microscope, my satisfaction was complete. I learned to make slides, and thereby hangs a truly Victorian tale.

When I was eleven, I discovered a little boy about a year older who had similar tastes. I used to go to tea with him, and to his nurse’s horror we spent hours together in his bedroom making slides and looking at them. These highly improper proceedings had to be sanctioned by the parents of both sinners before we could be allowed to seclude ourselves in so unseemly a fashion! Then there were the long and happy hours spent at the Natural History Museum, identifying various specimens and the never-to-be-forgotten afternoon when the Director (he called me ‘madam’!) invited me, subject to my nurse’s permission, to come downstairs and help his young men to name their shells. I had tea with them and was fully convinced that they needed my assistance, and my brother was not asked too, and altogether it was a delightful and wonderful experience and one which filled me with self-importance.

Kindergarten days over, I was sent to a select private school because Notting Hill High School was at least twenty-five minutes’ walk from our home and the nursemaid could not be spared to take and fetch me. Besides I might have made friends there with tradesmen’s daughters or someone equally undesirable! However the Doreck College was very good in its old-fashioned way, and I was well taught and spent four happy years there before I was sent, when just fourteen, to Hanover to learn German, and also to be turned into a ‘young lady’ and acquire some of the feminine accomplishments I refused to have anything to do with at home.

It was not uncommon at that period for girls to be sent abroad to a finishing school, though more often to Paris than elsewhere. The Hanover school to which I went was kept by an English woman, a friend of my mother in their youth, and many girls in our circle went there. It was very cosmopolitan in its clientèle and most of the pupils were between sixteen and eighteen years of age, so I was among the youngest. The teaching and methods were entirely German, and the English head died and was succeeded by a German while I was there. We were thoroughly instructed in modern languages, in German, French and English literature, universal history (not then a subject often taught in English schools) and history of art. Arithmetic was rudimentary, and at fourteen I already knew a good deal more of that subject than my foreign schoolfellows and did not add to my knowledge while there. We learned no Latin and no mathematics or science, but at that date that would probably also have been the case at a private school at home.

What most perturbed me was the unblushing way in which all, except the English girls, read their lessons from books concealed under the desk and otherwise cheated – doubtless because no-one was believed to be truthful without proof. I was of course used to the opposite method: at home every child was trusted unless discovered to be a liar, and I suffered a good deal from the unwonted treatment and its effects on the girls’ morale. I also disliked and never got used to the system of favouritism and spying which prevailed, nor to the encouragement of tell-tales. On the whole, however, I was very happy in Hanover and stayed an extra session by my own desire – a fact which made my last year one of continuous spoiling by the authorities, with repeated visits to the theatre and the like, from which my alleged ill-conduct had almost wholly debarred me during my first years at the school. The Hoftheater in Hanover had very good companies, and the performances of classics and modern drama were a pleasant way of improving our knowledge of the language. Twice during the summer holidays I went with the school to the Harz Mountains and on other occasions visited the homes of fellow pupils in other towns.

Kaiser Wilhelm had only recently succeeded to the throne when I went to Hanover, and I well remember how the ‘Reise Kaiser’ was criticised by his subjects as compared with his father, the ‘Weise Kaiser’, and his grandfather, the ‘Greise Kaiser’.1 He arrived unexpectedly at Hanover one morning at about 3am and made a tremendous to-do because at that hour there was not a proper turnout of the guard at the barracks. Later in the day, he rode past our Pensionat and, to our great satisfaction, stopped to salute our Union Jack. A subsequent memory is of a visit to a former schoolfellow in Berlin who feared I should be arrested for lèse-majesté if I expressed my views so openly as I was doing in a café, where they might be overheard.

Apart from school altogether, I had the inestimable benefit of living at home in a house that was full of books, to any and all of which I had access. My mother was herself an omnivorous reader and an exceptionally intelligent woman. Luckily she also held the opinion that it would do far more harm than good to try to control my reading. So I read everything I could lay my hands on – boys’ books by Henty, Ballantyne, Kingston, Anthony Hope, Manville Fenn,2 etc., girls’ books (usually very inferior to those meant for boys), nursery classics, such as Miss Edgeworth, Harriet Martineau, Charlotte Yonge, Mrs Molesworth, Mrs Ewing,3 and Lewis Carroll; grown-up classics such as Scott, Dickens, George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë; dozens of three-volume trash from Mudie’s4 which had the beneficent result of putting me permanently off that kind of thing later on. I also devoured many books that dated from my mother’s childhood or were at any rate old-fashioned in my time – Miss Porter’s Days of Bruce, Queechy and The Wide Wide World (many grammar lessons were enlivened by surreptitious counting of the number of times the heroines cried and fainted); Peter Parley’s Voyages, Mrs Markham’s Histories, even Magnall’s Questions, Little Mary’s Grammar and The Parent’s Assistant.5

We took in Little Folks and the Boys’ Own Paper; the grown-ups read all the better periodicals from which I was at liberty to extract what I could; my eldest brother was at the period engrossed by Carlyle, RUSKIN and by such lesser reformers as Bellamy and his Looking Backward.6 If I did not read through all of these, at least I knew what they looked like and the kind of thing I could find there. Hugh Miller7 and Charles Darwin I did tackle seriously, and the first book I ever bought with my own pocket-money, supplemented by a final 2/– from my father, was a complete Shakespeare in thirteen small volumes in a red case. I have it still, much thumbed and rather decrepit but very precious. We ‘did’ Shakespeare plays at school in the old Clarendon Press edition, and to this day I know most of Henry V by heart – the first complete play I studied. Not even analysis and parsing of the great speeches and learning all the abstruse ‘notes’ verbatim could spoil the thrill of the poetry. How well I remember teaching Nurse the speeches by heart while she brushed my hair in the mornings, and how I loved to declaim ‘Friends, Romans, Countrymen’ to anyone who would listen, or for my own delectation when no-one could be found. My father was very strict about slang and bad language. But what could be said to my shout of ‘The devil damn thee black, thou cream-faced loon’. ‘That’s Shakespeare?’

Except needlework, French, music and dancing, I loved all my lessons, even learning the queens of England, or jingles about battles of the Wars of the Roses, or the capitals and rivers of the countries of Europe or of the British counties, but Shakespeare came far away first. Once in the Christmas holidays some brothers and cousins and I went to the house of Miss Cowen, the actress (and a family friend) and read and acted with her A Midsummer Night’s Dream. What fun it was to be Hermia and abuse the hapless Helena! Those were the days of Irving and Ellen Terry, and we were taken to see them act at least once a year, and whatever the ornateness of the staging or the unwarranted alterations of the text, nothing could spoil the plays in a child’s eyes. Irving as Richard III or Shylock, Ellen Terry in any and every part she adorned – these were revelations which nothing can efface or render less memorable.

Of course our ‘treats’ were not always of so improving a nature. The zoo (with a ride on the elephant or camel), fireworks at the Crystal Palace, German Reeds with Corney Grain and Grossmith, Maskelyne and Cooke’s8, Mme Tussaud’s, Gilbert and Sullivan (The Mikado when it first appeared was my first play, in the evening of such a snowy day that it was doubtful if my grandmother’s coachman could get us to the theatre), pantomimes at the Aquarium (Drury Lane pantomimes were considered too vulgar for us children), circuses, magic lantern shows at the Polytechnic9 – we sampled and enjoyed them all, even a stage adaptation of the sentimental Little Lord Fauntleroy. Nor must the Lord Mayor’s Show days be forgotten, when a relative invited all his young friends to view the procession from his warehouse in the City, entertaining them afterwards to a sumptuous spread.

Once every summer Grannie took us to Buszard’s10 for strawberries and cream and ices – an event not to be underestimated by those who have been used to tea-shops and restaurant meals all their lives. In my young days there was nowhere where one could drop in to lunch or tea as a matter of course and ordinary middle-class folk went home or to their friends for tea, unless on some very special occasion. I remember many, many years later, on the day when the then Duke of York (George V) married Princess May (Queen Mary), one of my brothers and I stood for hours in the crowd to see them drive to and from Westminster Abbey. On our way home, tired and thirsty, we walked all down Regent Street and Oxford Street before we were able at last to get a cup of tea at the corner of North Audley Street close to Marble Arch. There had literally been nowhere else to go.

Another frequent summer expedition was a drive to Richmond with my grandmother; this included always a visit to the Maid of Honour cake shop, a stroll in the Park to see the deer and sometimes an hour in a boat on the river. Every year too we went to Kew Gardens and sometimes for Sunday afternoon walks in the country with Brownie or my father. When the Metropolitan Railway was extended to Rickmansworth, then a village, I remember a visit there because for the first time I saw a man in a smock-frock who pulled his forelock as a mark of respect to the gentry. Another country jaunt stands out in my memory because of a fight with the big brother who was taking me and who, in spite of the heat and the smelly inside, would not allow me to go on the top of the bus because of the impropriety for a girl of such a proceeding. I had to submit as the only alternative to an ignominious return home.

In one matter, however, we were allowed to ignore convention; I suppose we were almost the first ‘respectable’ children to take out picnic teas in the Gardens on warm summer afternoons. Very often we dashed off afterwards to meet our father on his way home and to dive into the tail pockets of his frock coat to see if he had brought us a box of Lombard chocolates. ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, until I hear whether you have been good children’. But we never had, so we seized on the delectable oblong pieces of chocolate in their paper wrappings with a blue bee on the outside before there was time for adverse reports. The frock coat and high hat were my father’s invariable costume in London: never, until he retired at the age of seventy, did I see him otherwise clad in Town, and even in the country he never wore ‘knickerbockers’. He celebrated his retirement by the purchase of a square bowler,11 much to the distress of my mother and self, who regarded it as an outrage. It was only after his retirement that he would be seen carrying even the smallest parcel, that being incompatible with professional dignity. Similarly with smoking – and he was an inveterate smoker. He lit his pipe as he entered the Park on his way to the West End, and he carefully extinguished it when he reached Grosvenor Gate. When he got to his consulting rooms, he changed his coat and ate a pastille so that no odour of smoke should hang about him. Nor did he smoke again until in the Park on his way home. The embargo on a cigar would not have been so severe, but ‘gentlemen’ could not publicly indulge in pipe smoking, and cigars were not only an extravagance but also much less satisfying.

My father was an ardent Conservative to whom the name and thought of Gladstone were anathema and Home Rule an inconceivable outrage. My earliest political recollection is of the death of Beaconsfield.12 My father was tossing me in his arms and I, rather giddy, was nearing the ceiling when I heard him say to Nurse, ‘Well, Barker, what do you think about the death of Dizzy?’ I suppose I thought there was some reference to my sensations at the moment – anyway I have never forgotten the event, though I do not remember the Fenian outrages nor the murder of the Czar13 which took place within the year. Another unforgotten date is that of the battle of Tel el-Kebir.14 The one thing I really feared was men shouting out news after I was in bed, and that was what happened on that Sunday, Barker’s Sunday out, and to add to my grievance, it was on my birthday – the ninth – when nothing ought to have been allowed to frighten me and make me unhappy. Yet another remembered political happening is being taken by my father to hear a speech by Lord Randolph Churchill.15 I have no idea of the subject and no recollection of the speaker, but I know the meeting was after dark – I suppose on a winter afternoon – and at Paddington Baths16, and that I went alone with my father and sat on his shoulder so that I might see.

I was nearly twelve at the time of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, but the news of an uncle’s death arrived while I was helping to decorate the balcony with flags and fairy lamps, so we did not go to see the procession next day. It still amuses me to remember that this disappointment did not prevent me writing the best composition on the subject, though I was the only girl in my class who had not seen it.

The Queen seems to play a great part in my childish recollections. It was my grandmother’s frequent habit to drive with me up and down the Park until the Queen had gone by, and we children sometimes went to Paddington Station when there was a royal migration to Windsor. Queen Victoria may have passed through a period of unpopularity in earlier times, but that was long before, and all through my childhood and until she died, she stood, for most of her subjects, as the visible symbol for their love and loyalty to the Empire to which they were proud to belong. In the eighties and nineties we had no doubts of its justification and greatness, and the Queen was its protagonist and the beloved mother of its peoples. Her death in 1901 was rightly felt to mark the end of an epoch, but it was also mourned as a personal loss by almost all her subjects. The day of her funeral procession was one of profound gloom; Londoners wore only black, and I have always thought Mr Noel Coward’s whistling errand-boy episode in Cavalcade untrue to fact. I do not think any London boy, however light-hearted or thoughtless, would have whistled on that day.

I saw the procession from a stand in Hamilton Gardens and well remember that though the Park was black with spectators as far as the eye could reach, and even in the trees, there was such absolute quiet that one could hear the tramp of the soldiers’ feet as they marched down Piccadilly and turned in at Hyde Park Corner on their way through Marble Arch to Paddington Station. When the procession passed us, the Kaiser was doing his best to draw level with the King, who, as chief mourner, naturally was intended to ride immediately behind the gun carriage on which the coffin was borne. I believe that little bid for precedence went on throughout the slow march, but King Edward held his own with unobtrusive and dignified determination.

* Children of both sexes wore sailor suits when small, and boys until they were 11 or 12. Boys were not breeched until much later than at present, and there was at least one occasion when I rejoiced in being taken for my brother by some short-sighted old lady who had the excuse that we were dressed alike and that my hair was at that date cut short like a boy’s.

1 1888 was the year of the three Kaisers: Wilhelm I, der greise Kaiser – the old Kaiser; Frederick III, der weise Kaiser – the wise Kaiser; and Wilhelm II, der Reise-Kaiser – the travelling Kaiser (sometimes referred to as ‘der Scheisse-Kaiser’).

2 Henty, Kingston and Fenn were prolific, writing over 400 novels between them. Ballantyne, best known for The Coral Island (1857), had worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company and set many of his novels in Canada. Anthony Hope was also prolific but is best remembered for The Prisoner of Zenda (1894) and Rupert of Hentzau (1898), neither specifically for children.

3 Maria Edgeworth was a prolific Anglo-Irish novelist and educationist who, with her father, wrote largely moralising stories for early readers. She is best known for The Parent’s Assistant (1796), a collection of children’s stories; and for an adult novel, Castle Rackrent (1800). Harriet Martineau was a writer and journalist of radical political and dissenting views, an abolitionist and early sociologist. Her collection of children’s stories, The Playfellow, was published in 1841. Charlotte Mary Yonge was a prolific and highly regarded English novelist, mainly writing for young girls. Her most popular novel was The Heir of Redclyffe (1853), and she edited the girls’ magazine The Monthly Packet 1851–90. Mrs (Mary Louisa) Molesworth’s books were typical of late nineteenth-century writing for girls; her best-known titles are The Cuckoo Clock (1877) and The Carved Lions (1895). Juliana Horatia Ewing wrote children’s stories and several novels, including the bestselling Jackanapes (1879), and edited The Monthly Packet and Aunt Judy’s Magazine.

4 Mudie’s was a circulating library started in 1842 by Charles Edward Mudie. He became hugely successful by undercutting his rivals, charging at the start only a guinea a year. The library had an enormous hall like the British Museum Reading Room and was comparable in size with a major academic library. It closed in 1937.

5 Jane Porter was the author of The Scottish Chiefs: A romance (1811). Days of Bruce (1852) was in fact written by Grace Aguilar, an English novelist, poet and writer on Jewish history and religion. Queechy (1852) was a sentimental novel by American novelist Elizabeth Wetherell, the pseudonym of Susan Bogert Warner, who also wrote the hugely popular The Wide Wide World (1850). American author Samuel Griswold Goodrich’s Peter Parley’s Annuals, which covered geography, history and science, among other subjects, appeared from 1827. Richmal Mangnall’s Historical and Miscellaneous Questions for the Use of Young People (1800) was generally known as ‘Magnall’s Questions’. Jane Marcet published many ‘Conversations’ on mainly scientific subjects, as well as Mary’s Grammar; interspersed with stories, and intended for the use of children (1835). Mrs Markham was the pseudonym of Elizabeth Penrose, whose history book for children on England (1823/1826) was the most popular textbook of English history for four decades.

6 The American author Edward Bellamy’s utopian science fiction novel Looking Backward: 2000–1887 (1888) was a bestseller in its time and has remained in print ever since. It became hugely influential shortly after publication, prompting the emergence of a political movement; it also inspired a number of utopian communities.

7 The geologist, writer, folklorist and evangelical Christian Hugh Miller wrote several geological works and disagreed with Darwinian evolutionary theory, expressing in his book Footprints of the Creator (1849) his view that the different species were not the result of evolution but the work of a benevolent creator.

8 Thomas German Reed founded his German Reed Entertainments company in 1855, providing gentle, intelligent, comic musical entertainment suitable for children. Corney Grain was a member of the German Reeds and a singer and performer of comic musical sketches at the piano. George Grossmith was a great friend and rival of his, and the original singer of most of the patter songs in Gilbert and Sullivan, despite having no singing voice. He was also joint author with his brother of The Diary of a Nobody (1892). John Nevil Maskelyne and George Alfred Cooke were English magicians who invented many illusions still performed today. They made their theatrical debut in 1865. Maskelyne was also a successful inventor; among many others, he took out a patent on a coin-operated lock for public lavatories (1892), which was used in England until the 1950s.

9 The Royal Polytechnic Institution was famous for its spectacular magic lantern shows. It had huge screens and provided accompanying musicians and a team of people to produce sound effects to enhance the performance.

10 Buszard’s cake shop was located at the west end of Oxford Street. They became famous for setting up tables and chairs in Hyde Park during the 1851 exhibition, serving drinks and cakes.

11 Square bowlers were worn by coachmen, hence the outrage.

12 Benjamin Disraeli (1st Lord Beaconsfield), statesman and novelist, was Prime Minister briefly in 1868 and 1874–80. William Ewart Gladstone was a Liberal statesman and four times Prime Minister (1868–74, 1880–85, 1886 and 1892–4).

13 Czar Alexander II was assassinated March 1881; the Fenian bombing campaign was from 1881 to 1885.

14