2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

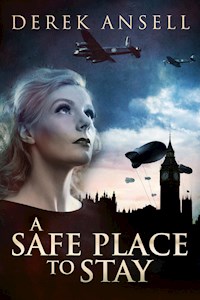

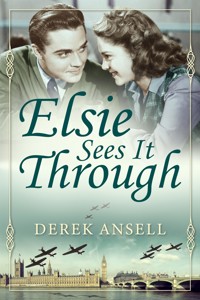

London, 1943. The War in Europe is raging. After Elsie bumps into a young soldier, they are both attracted to each other and in time, become close friends.

Elsie lives with her widowed mother in a small North London house and has a close relationship with her long-time friend, Julia, who would like that relationship to become more personal and intimate. After the young soldier Brian proposes marriage to Elsie, she doesn't know who to choose.

Conflicted, Elsie doesn't know what she wants, or what she believes is her destiny. While sweeping changes take place across England and the rest of the world, Elsie must come to terms with her life and her future, and navigate a difficult, thorny path to happiness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

ELSIE SEES IT THROUGH

DEREK ANSELL

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Epilogue

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2022 Derek Ansell

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Terry Hughes

Cover art by Lordan June Pinote

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

CHAPTERONE

LONDON, WEDNESDAY 28- JULY 1943

A young woman is finishing work at noon. She stops typing her last document, puts it to one side and tidies her desk. Into the top drawer, she places her notebook and personal papers; her bits and bobs and a written reminder of something she must do on the next day. Then she rises from her desk and walks out to the ladies’ room, where she pats her long hair into position, pulls a face in the mirror and decides to add a little lipstick. She applies it, then puts her bottom lip over her top to smooth it and ensure that it is not too little and not too much. Then she reverses the lip movement. She has a round face, with slim, dark eyebrows but not, she decides, an unattractive look. Fairly ordinary, maybe, but her shoulder-length light-brown hair sets it off and her eyes, a greeny-grey colour, are quite striking. She has been told that frequently. Satisfied, she moves to go but thinks about how long she will be out in the street and decides to sit on the toilet. When she finishes, it takes only a minute to wash her hands, take a last look into the mirror and leave the room. Walking across the corridor slowly she notes the time on the big ticking clock on the wall and moves towards the room opposite her own. The prospect of an afternoon off is appealing and she has decided to spend it walking around town. Two things are nagging away at her ever-active mind, her mother’s health – always precarious – and something her friend Julia said last night. This, though, is not the time to be thinking about that. She enters the office.

“I’m just off on my way now, Mr Simpson,” she says.

“Yes, all right, Elsie,” he replies without looking up from his desk. “See you in the morning.”

She smiles. All at once, she takes in the room with the faded sunlight on the window sill which she can see clearly outside; the mixture of dust and recent tobacco smoke still lingering on the air and the heavily built form of Mr Simpson sprawling in his large chair, his look of concentration as he stares at his papers, his fancy waistcoat. All this she sees without consciously realising it and proceeds down the stairs to the reception area. Then she leaves the building.

At first, she had been surprised when Mr Simpson told her she could have the afternoon off. She told him she was quite happy to work on. Again, she smiles. If Simpson was giving her an afternoon off, it was because he wanted her in all day Saturday; she knows that. It has happened before. Today is Wednesday, tomorrow he will tell her it is for urgent war business, and she will have to come in. All day. The typing of important army contracts that must be watertight. And she will have to come in at least an hour earlier than usual. She knows the drill.

Elsie begins to walk along the Strand towards Trafalgar Square. It is a warm day, hot, muggy and dusty. The sky is a greyish white with patches of blue. Sunshine breaks through intermittently, at intervals. She is jostled suddenly by an airman who is engaged in animated conversation with another man in uniform and he barely notices her. She is suddenly amid a flurry of people, soldiers, sailors, airmen and civilians, all in a rush. Time to grip her handbag tightly as you never know in these situations. Walking on, she passes the Tivoli cinema and notes that there are a good number of people on the move. More military personnel of all shades than civilians, although the latter stand out for their lack of colour in their drab suits or dresses, coats and shoes. There are, she notices and not for the first time, many foreign soldiers and sailors, their uniforms showing where they come from by the changes in style or design or the shoulder badges that say Canada or Australia or, sometimes, other locations such as Poland. A bus draws up noisily by her side at a request stop and two people alight. Elsie frowns as she glances across at the bus. She still can’t get used to seeing all the windows blocked up with harsh green netting, leaving only a small triangle of glass for passengers to look through. It is, her uncle has explained to her, a precaution against bombs and explosions sending shattered glass flying everywhere and causing yet more injury to pedestrians. Logical really, she says to herself, although she still cannot get used to it.

The thought of her mother’s declining health surfaces again, unbidden, into her thoughts. It was the reason she had to turn down the chance of sharing a spacious bedsit with Julia. She could never leave her mother on her own. Never ever. And what was Julia’s response? That she’d have to face up to it sooner or later? Face up to what? Leaving her mother or, more likely, moving in with Julia? Well, it is not going to happen, and Julia must think what she likes. It isn’t that her relationship with her mother is bad, it certainly is not. Both are strong characters with definite but often conflicting ideas about how a house should be run. Elsie well remembers being pushed and prodded into tidiness, as a young girl but it was a lesson well learned, even if her own ideas went further than her mother’s ever had. Well, if things need doing at home, she will see they are done. If only her mother would let her get on with it and not keep complaining and bitching constantly. She, Elsie, will have her way in the end, just see if she doesn’t.

At Trafalgar Square, the fountains are sending up white sprays of water, the pigeons are circling in the air ready to land and many are already on the paving stones. Suddenly there is a drone of aircraft from above, and Elsie looks up nervously, as she and everybody does these days. She sees two low-flying silver British fighter planes with the red, white, and blue markings of the RAF clearly visible. A sigh of relief at a time when the sound of aircraft inspires fear and loathing. Always. The little boys watching the pigeons and feeding them, even though the sign says this is forbidden, have looked up swiftly, noted the aircraft make and carried on with their pigeon-watching. Elsie stands, watching the people and birds all around her for a few minutes and then walks away and crosses the road. She wonders how she will fill the next few hours, because she has made no plans. She will not go home, though. There are better ways to spend an afternoon off than listening to the endless nagging, or complaining, or both, of her mother. She wonders, as she does frequently now, why she is still living at home at the age of 30. She smiles ironically as she recalls that it was originally because she did not want to leave her mother on her own after her father died. And when the war broke out, there was even more reason to stay, turning down the very first offer of a rather nice bed-sitting room found by her friend Julia, that they could share.

She misses her father she always has, ever since the day he died. Always will, she acknowledges. He it was that encouraged and nurtured her love of books and music. Elsie reflects that it was her father’s sudden and unexpected fatal heart attack that heralded the beginning of her mother’s gradual retreat from an active role in running the house. But, if she relinquished most of her active participation, she more than doubled her criticism, complaints and insistence that Elsie was incompetent.

A little circle of people, some in uniform, are waiting outside the National Gallery to enter for the lunchtime concert. Elsie has fond memories of lovely music there, watching Myra Hess, Benjamin Britten and others playing. Peter Pears and Kathleen Ferrier singing. The enclosed, crowded room, the sombre faces of the men and women in the audience and the rich, emotive music swelling up in the warm, charged atmosphere. A Mozart sonata rising to a brief crescendo and fading down again, gently. Not today, though; this is a day for walking and thinking. And reflection. Discovery perhaps? Elsie gazes speculatively ahead towards theatreland. Where to go next?

She walks on, up the Charing Cross Road and then cuts through to Leicester Square. More people are on the move now, some walking slowly, others seeming to be driven by an urgent desire to reach a destination. Elsie moves slowly round the square, turning left before reaching the Odeon cinema and walking up past the people in the centre and past the Leicester Square Theatre. In the distance, she hears an ambulance bell and wonders if a bomb has dropped suddenly, miles away. She does not recall hearing it, but the sounds of the city are all around, some near, some far and constantly supplying a symphony of noise. She stops walking, pauses. She proceeds into the square and sits on a seat looking out towards the Odeon. Time for reflection. Where is she going? Not just on this casual afternoon walk but for the rest of her life? She feels reasonably content, work is going well and she enjoys it. Life at home can be irritating at times with Mother the way she is but they get along somehow. Most of the time. Just the one, particularly close friend, Julia and they go back many years, to school days, indeed. Julia can be possessive, smothering almost sometimes. Julia can be a little embarrassing at times, too, but Elsie can handle her, no problem there. She smiles. After all, she is reliable, loyal, always there for when she needs a friend most.

No male friend on the horizon, though. She frowns. Perhaps in good time, who knows? She doesn’t, that’s for sure. Not that she has ever had or desired much communion with men or boys. A smile returns on her face. Well, no point looking into the future because you can’t see anything there. Looking ahead, across to the other side of the road, she sees the milk bar. Then the Empire cinema and the little Ritz theatre next door. She walks on and joins that pavement. It is crowded, perhaps the most packed of all the streets she has passed since leaving her office. Far more people, more beige and plain grey clothing and the usual assortment of army, navy, and air force personnel. The sudden rumble of a heavy truck passing, together with another aircraft passing overhead, intensifies the noise level and causes Elsie to blink and feel a momentary spasm of fear. It is all right, she convinces herself, just traffic and sundry noises but she is nervous when hearing loud sounds, as everybody is now. As everybody has been since being pounded by bombs falling, night after night after night. Houses destroyed. A gap in a large terrace of Georgian or Victorian houses with a huge pile of rubble where a house used to be. New houses crooked and wrecked like piles of twisted masonry and firewood.

Elsie shakes her head, and a little voice inside tells her to think about something else. She walks past the milk bar and the Empire and recalls that the hugely popular film, Gone With the Wind, has been showing there for more than two years. A glance to her left tells her that it is now showing at the little Ritz cinema, so it must have transferred there at some point. She hasn’t seen it as she objected to paying the much higher charges for seat prices for that film. She knows, too, that it runs for more than three hours and that is longer than she feels comfortable, in a cinema. She keeps on walking, past the Warner cinema farther down the road and back to the Charing Cross Road.

It isn’t just the sights and sounds of London’s West End that fascinate Elsie. It is the odours, many and various. The blast of perfumed, warm air that emanates from a side door of the Warner cinema as she passes by, looking along the alleyway at the side. The rush of neutral air that comes from the entrance to the Underground station as she walks past it. Then there are the fresh, temping food smells from the restaurants. The fresh coffee odours. So much to take in being in Central London, really. She passes the advertising hoardings and briefly notes the encouraging words and pictures that want her to buy Sharp’s Toffee and Peek Frean’s Crispbread. Or should she purchase some Vani-Tred shoes? They look much more comfortable on the hoarding pictures than the ones she is wearing now. Or a pair of Dolcis shoes? And the stockings and underwear from Morley look very luxurious and comfortable. Maybe she should settle for a bottle of Wincarnis Tonic Wine to take home for supper tonight? She smiles. A flippant thought, that.

Walking on, she passes the last of the hoardings which offers less frivolous and selfish advice. The long, ugly face of the Squander Bug, all fierce, sharp teeth and bulging, manic eyes and underneath the picture she is implored not to waste money on things she doesn’t really need but to buy war bonds and savings certificates to help the war effort. We must all, Elsie intones under her breath, help the war effort. She would like to make a bigger contribution, if only she could.

Ten minutes later, Elsie, rather tired and dusty, warm and with the realisation that her feet ache somewhat, is aware that she is very thirsty. Up ahead she notices a canteen.

CHAPTERTWO

BIRMINGHAM, WEDNESDAY 28 JULY 1943

The house is semi-detached with two bay windows, one up and one down. It is an almost-new house, built in 1939, just before the outbreak of war. In the upstairs front bedroom, the one with the upper bay window, a young man is putting on his army uniform. He is standing in the master bedroom of the house. It is the room that his parents planned to occupy when they bought the house early in 1940 and would have done if it had not been for the garden. The young man’s mother loves the garden. From the rear, slightly smaller bedroom, she has a good view of it. The garden is long and rather narrow and affords a view of allotments in the distance where the young man’s father now spends his rare leisure time. He is vigorously growing vegetables of all sorts in answer to government pleas to Dig for Victory.

The young man, not so young, really, as his father points out, has just celebrated his 32nd birthday. Yesterday. His leave is nearly over and he must return to his unit. Although not due back until midnight, he has decided to leave early and spend part of the day in London. As a man alone on leave from the army, he has found it difficult to occupy himself. His friends are all away and he has no girlfriend. His father and mother try to engage him in conversation frequently, but he finds that he has little to talk to them about. His relationship with his father is often difficult. His father is a strong, sinewy man who spends most of his life on the assembly line at the Austin Motor works at Longbridge, now making aero parts for the war effort. He works long hours and often volunteers for extra shifts and earns good money. Enough to buy this new house on mortgage and own his own small Austin Seven car. Brian, his son, thinks he has little in common with him and takes after his mother, an altogether quieter and gentler creature.

Brian puts on his army shirt, a coarse-grained garment and then puts on his battledress tunic. The tunic has one stripe on each sleeve, denoting his rank of lance corporal. He goes over to the mirror in his wardrobe and starts to comb his big shock of red hair that sticks up somewhat at the front. Normally it looks good but now, with the back and sides of his head cut noticeably short in army-regulation mode, it appears somewhat incongruous. He frowns and then pulls a face at the mirror. His face is soft, the eyes blue, his expression, when not frowning, is pleasant, not unlike his mother but masculine. He picks up his forage cap and walks out of the bedroom and goes downstairs to the kitchen.

“I’ve made you a coffee, Brian,” his mother says, smiling. “Get it down you.”

He nods, smiles, and thanks her as he sits down at the kitchen table. His father, looking grizzled and unshaven and still in just his vest and trousers, glowers at him. “What time is your train?” he asks.

“Half ten,” Brian answers briefly, not looking at his father.

“Are you ready to go?”

“Well, you’re not,” his mother says, addressing his father and, before he can reply, adds: “Best get yourself tidy. Now.”

His father grunts, clears his throat and pushes back his chair, noisily scraping the kitchen tiles. He goes out of the room, saying, “I won’t take a minute,” and his mother sits down at the kitchen table. She takes a sip of coffee from her half-finished mug. Brian asks what is wrong with his dad as he takes his first sip of hot coffee.

“Oh, he’s just fretting at losing half a day’s pay,” she replies. “Take no notice. He spends most of his life at that plant.”

“I didn’t ask him to take me to the station,” he says. “I could easily get the bus.”

“Your dad can take you,” she says firmly. “Do him good to get away from that works.”

She asks him if he has enjoyed his leave. He nods brightly but she shows concern that he hasn’t done much. He seems to have spent most of his time in his bedroom or down at the pub.

“There’s not much to do, Mum,” he tells her. “All my mates are away in the army or RAF. We never seem to coincide when we’re on leave.”

“You should get yourself a girl, Brian,” she murmurs wistfully. “Bright lad like you.”

“You don’t just go and get a girl,” he growls irritably, “Like picking up a loaf at the bakers. And I’m no longer a lad.”

“No, you’re not,” she agrees. “Time marches on.”

It does indeed and he finds his attention drawn to the big clock on the wall, ticking away the seconds steadily. It is not time to move just yet, so he takes out his packet of cigarettes and offers one to his mother, who shakes her head. He lights one himself and sends blue smoke curling towards the ceiling. When his father reappears, he has shaved and fitted himself into a tight dark-blue suit. “Time to make a move,” his father growls irritably.

“Let him finish his cigarette, George,” his mother says, “for goodness’ sake.”

When he walks out to the little Austin Seven parked at the kerbside, he turns and waves goodbye to his mother who is clearly fighting back the tears. His father is already in the car, starting the engine. When the car starts to move, he is silent at first, thinking that he won’t be sorry to get back to the barracks. He has been bored on leave with no mates around and only his parents for company. He suddenly becomes aware that his father is telling him, in a loud gruff voice, that he should have been getting out and about more on leave and not just been cooped up in his bedroom most of the time.

“There wasn’t much I could do,” he points out.

“You could’ve come down my works club. We got cheap beer, darts, bar billiards and all sorts.”

“Not really, Dad,” he says, smiling. “Not my sort of thing at all.”

His answer seems to irritate his father, almost to make him angry. “You’re an ungrateful bugger, you,” the older man says. “No matter what anybody tries to do for you. And you’re incredibly lucky, do you realise that? I tried everything to get back into army uniform, but they wouldn’t take me.”

“You’re too old, Dad,” Brian replies, smiling. “But you did your bit in the first war.”

“Too right I bloody did. And I could show all those young raw recruits a thing or two today.”

Brian shakes his head and lapses into silence. Sergeant Crawford is reliving his past glories in the Great War. And bitterly resents the fact that they won’t let him join in this one. He is forever talking about those days, glorifying them; reliving his great adventures as though it was all a marvellous time and not the great tragedy that it truly was.

At New Street Station, it is all hustle and bustle. People are crowding into the station entrance, mostly in uniform, some carrying kitbags, all seeming to be in a hurry. Some women are bidding tearful goodbyes to their men near the entrance, reluctant to go into the station for the final farewell. For some, it will be a last farewell. Their men returning to their units, to go to war. Some, at home, will die in air raids although the bombing has become less and less this year. Brian gets out of the car with his father, and they shake hands. He says goodbye and asks his father to take good care of his mother.

“Never mind that you, cheeky bugger,” his father growls. “Get some service in and don’t come back next leave a lance-jack. Get some bloody stripes on your sleeve.”

On the platform, Brian is trying to find a small space where he can feel free of bodies all around him. The platform is absolutely crammed with men and women, kitbags, and suitcases. Most are in uniform of one sort or another. Looking up and down the platform, Brian thinks it will be almost impossible to get a seat on the train to London. Too many people on the move, he thinks, forgetting for the moment that he is one of them. He decides he would like something sweet on the journey. He would love a Mars bar, one of his favourite confections, with its thick milk chocolate, caramel layer, and nougat filling. They are available only in the south of the country now, though, since the outbreak of war. Sharps the word for toffee, he recites under his breath as he advances, pushing towards the kiosk. There is a chocolate machine with Nestlé bars available, but he decides against and goes on and buys a bag of toffee.

His decision to walk up to the top of the platform pays off. As the big locomotive comes steaming in, black smoke billowing from the funnel and a grinding noise as the train shudders to a halt, he is lucky enough to reach the door before anybody less agile. He is in swiftly and, although the corridor is crammed with soldiers and airmen and a well-built woman in her fifties, he manages to squeeze into the middle of a seat with four other people already in position. Soon he is on his way with everybody around him looking hot and uncomfortable. As the train pulls out of New Street Station, he gazes out of the window at the hoardings advertising Bile Beans and Bovril. Some combination, that.

As the train gathers noisy, rattling momentum, he stares straight ahead, avoiding the eyes of passengers facing him, as far as possible and then looks upwards. He notes the evil eye of the Squander Bug in a panel advertisement just under the luggage rack and begins thinking about getting back to camp later that evening. He feels happy about it and, although he does not take naturally to the regimentation and strict discipline of service life, he is beginning to make and maintain new friendships at camp. He thinks back to his last conversation with his mother before leaving and acknowledges to himself that she is right. He should have a girlfriend, it is nearly four years since his last one ended it. But you don’t pick a girl out of thin air or bump into one in the street, do you? And there are only the dance halls now, which he does not like. Where else would you look?

There are only two women in the carriage, the stocky middle-aged and rather matronly figure he saw when entering the carriage, who now sits opposite him, and a small WAAF girl in the corner seat by the window who has had her face in a book since pulling out of New Street. Brian glances at her in her smart air-force-blue uniform but realises she is most likely not even aware of his existence. She has only looked up three times to the best of his belief since leaving the station and that to glance briefly out of the window and straight back to her book. A sailor and a civilian in a faded brown suit both light up cigarettes simultaneously and a cloud of blue smoke fills the carriage. The woman opposite coughs loudly and a man in the far corner seat rises silently, without a word to anybody, and pulls down the strap far enough to allow fresh air in from the window.

At Euston Station, the rush is on to get out of the carriages and get clear of the platform, out to the street or the Underground trains. Brian is in no great hurry; he has the rest of the afternoon to himself, he reflects as he takes his time to move out of the carriage and waits for the great surge of people to disperse. Smoke and steam from the engines hang in sulphurous patches in the air. Finally, he joins the stragglers at the end of the train and walks leisurely along and out of the station. He walks down toward the high, sooty black pillars of the great Doric arches that form the impressive entrance to Euston Station. He stops, takes out a cigarette and lights it then stands there looking out towards the road.

When he begins to walk along the Marylebone Road, he is aware that the day has become hot, dull, and dusty. A large lorry rumbles past followed by an army armoured vehicle, escorted by two military guards on motor cycles. The noise of traffic is deafening for a moment. There are not so many people about now as it is the lunch hour; a few soldiers and airmen, some civilians and one or two police officers. He is aware of the artefacts of war in London all around him. The sandbags outside buildings, the Emergency Water Supply signs and the Dig for Victory and Make Do and Mend posters. He is alone and lonely again but on balance, he feels, better off. He can walk around and explore London, seek diversion or entertainment, and avoid sitting with his mother as she asks questions he would prefer not to answer.

It is quiet outside Madam Tussauds as he walks past. At Baker Street, he toys with the idea of spending an hour in the Monseigneur News Theatre but decides that newsreels about battles raging alleviated with a couple of cartoons would not suit his present mood. He turns around and begins to walk, briskly, in the direction he has come from. At Great Portland Street, he turns right and begins to head off in the direction of theatreland but still aimlessly with no clear idea of where he is heading or what he plans to do. He walks past a canteen and has only gone a few short paces when it occurs to him that a cup of tea might be a good idea at this point. He turns around and walks back in the direction he has come from.

CHAPTERTHREE

LONDON, WEDNESDAY 28 JULY 1943

It is all hustle and bustle in the canteen. Lights burn in the ceiling, but visibility is not good; cigarette smoke and steam hissing and floating upwards from the counter mingle in the tepid air. All the many tables are occupied, some with four or even five people huddled around. A colourful mix of uniforms is visible all round the big room; khaki, RAF, and navy blue. There are about 10 civilians in mainly drab clothing. Buckets filled with sand or water are placed on either side of the main door. As she enters and moves tentatively in the direction of the counter, carefully avoiding colliding with people standing talking or coming towards her, Elsie feels somewhat overdressed. She wears a smart pale-blue jacket and skirt and a cream-coloured blouse. The scarf at her neck is purple, arranged as a bow. Her flat shoes are black and very shiny. There is a little knot of people at the counter, a ragged sort of queue. A buxom woman in a grey coat with the words WVS embroidered on the breast pocket is serving from a large tea urn. As the soldier in front of her moves forward to add sugar to his tea, the woman faces Elsie with a half grin, half grimace and she says: “Yes, my love?”

Elsie asks for a cup of tea, pays for it and picks it up from the counter. She turns quite swiftly with her cup and saucer but fails to notice that the soldier in front of her has turned too and is walking forward. She can’t avoid colliding heavily with him knocking his tea out of his hand to crash noisily to the floor, smashing crockery and spilling the liquid out into a pool.

“I’m terribly sorry,” she says, wide eyed, staring at the soldier.

“That’s all right,” he tells her and smiles broadly. “Accidents will happen.”

As people back away from the mess, the buxom woman calls out to everybody to stand back; she will deal with it. Elsie blushes bright red. The woman soon appears with two large buckets, one for the broken crockery and the other with a big cloth. She gets down on her hands and knees and proceeds to clear up, tut-tutting as she works. Her grimace has now formed fully on her face and Elsie is embarrassed again. “My apologies,” she breathes, addressing the woman this time. “So careless of me.”

“Don’t fret,” the woman intones, and the grimace once again melts into a grin. “Happens all the time here, lovey, and I can deal with it. It’s being so cheerful that keeps me going.”

Elsie shifts her gaze to the soldier who has taken off his cap to reveal a thick crop of reddish-brown hair. He looks very boyish and young, she thinks. He has a nice, friendly face, too, she is thinking.

“Look, I spilled your tea; you must let me buy you another,” she suggests.

“No, no, don’t worry, I’ll get it.”

“Oh no, my responsibility,” Elsie insists, speaking in her most stern voice which surprises her and causes her to blush again. “I’ll buy your tea.”

“All right,” he concedes, smiling. “If you insist.”

Elsie very carefully puts her own cup on the counter and asks for another cup from a slim young girl, dressed like the buxom woman, who has suddenly appeared as her colleague mops up. As the little queue of people has dispersed owing to the spillage, only Elsie and the young man are left standing at the counter. He is looking at her intently and she feels his eyes burning into her face although she is not looking at him. She feels she is going to blush yet again so fixes her eyes intently on the girl serving her.

“It’s extremely kind of you,” the young man is saying, “but as you are buying my tea you must let me buy you something to eat.”

“Oh, no, no need, really,” she replies, unable to stop the flush on her cheeks this time.

“Oh yes, I must insist.”

She looks round nervously to face him and smiles at the same moment that he smiles at her. “Oh, all right, then.”

“One of those spam sandwiches?”

“Oh no,” she responds, realising too late that she spoke too quickly and harshly. No harm done though.

“No,” he agrees, “they are looking a bit grey. They don’t look very well, do they?”

“Not very,” she replies with a grin.

“Rock cake? How about a rock cake? They look nice and fresh and crusty.”

“Yes, please. Thank you.”

He suggests politely that he carry the teas and she the rock cakes. He points to a table over by a window where a young couple are just leaving. He says that they can bag that table if she is quick. He will take it slowly with the tea – we don’t want another floor drenching, do we? She hesitates just for a moment, thinking that he shouldn’t be assuming that they will be together but does, in fact, walk quickly over to secure the table, only a second or two ahead of two military policemen who are obviously heading for it. He joins her and places the drinks safely on the table and sits facing her.

Gradually, the canteen becomes quieter as more and more people drift off back to their places of employment or other duties. Elsie takes a drink from her teacup and sighs. The young man looks a little nervous and then clears his throat, ready to speak. As he looks at her face directly, he likes what he sees. She looks quite nice, he decides, not pretty in an obvious way but a pleasant, cheerful face. She is smart, too, well dressed and with good taste.

“I should introduce myself,” he tells her. “My name is Brian, Brian Crawford.”

“Hello,” she replies, grinning. “I’m Elsie.”

“Well now,” he recites sententiously, “a crash, flying tea and splintered crockery brought us together but that is no reason to spoil or interfere with a beautiful friendship.”

She laughs briefly and then looks down at the table. There is a short silence and then she feels it is incumbent on her to say something. He bites into his rock cake, pulls a face, and says: “Wow, these buggers are harder and probably older than they look. Excuse my French.” She laughs fleetingly and asks him if he is on leave from the army. He tells her it is just coming to the end of his leave, and he is returning to his unit that evening. He does not need to get back to camp until late that night so at this moment he is having a walk around London. Seeing the sights.

“Me too,” she bursts out spontaneously.

“You too?”

“I have an afternoon off so I’m walking round town.”

“Ah. Then perhaps we should walk around together, in that case?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” she murmurs nervously. She is looking at him intently now. She finds his appearance incongruous, really, as the thick shock of hair on top of his head seems to be out of alignment with the rest of his head. And his body. Then again, she considers, still studying him surreptitiously when he is not looking directly at her, he is not too bad looking and she is impressed by those big blue eyes. As to going walking with him, she is none too sure about that. They have only just met and through what many people would consider an unfortunate incident. She becomes aware though, as a voice intrudes into her reflections, that he is asking why not go together. They both have free afternoons, and they are both set on doing some more walking around town. What about it?

She shakes her head slowly and murmurs that she hardly knows him or anything about him. So, what would she like to know? he enquires politely. She eats a piece of cake, gazing at him and looking thoughtful.

“How long have you been in the army?”

“I was called up soon after the outbreak of the war.”

“Will you be going overseas very soon?”

He hesitates and looks vexed momentarily. Then he tells her that he will not be going overseas or fighting in the war. He had volunteered for active duty in the infantry, just like his dad had in the First World War but they told him he would be more use to the war effort in the Pay Corps, due to his civilian training as an accountant. He shrugs his shoulders and looks a little sheepish. Elsie is impressed. He is, she thinks very honest. He needn’t have told me that, she thinks, me, a stranger. She smiles.

“Me too,” she whispers.

“You?”

“Yes,” she confirms. “I volunteered to work in a munitions factory and do my bit for the war effort. Then they told me I would be more useful where I was as my work involved important documents and contracts for the armed forces. So here I am, in a law office, slaving over a hot typewriter.”

He laughs and she smiles in response. “There you are,” she hears him say, “we do have something in common and should be friends.” She is now looking thoughtful but does not reply. He is looking at her and thinking that it was probably her slim form and delicate features that convinced the authorities that she would be more use in an office than working with heavy metal parts and complex machinery. Lots of women do, he knows, but maybe they are of stronger build and tougher than her, physically at least. He does not share any of these thoughts with Elsie though but eats his last chunk of cake and then finishes his tea. Elsie is still sipping hers, peering at him over the rim of her cup when she thinks he does not notice. As she finishes drinking, he clears their cups to the side of the table and takes out his packet of Gold Flake. He offers her a cigarette from the packet.

“I don’t very often,” she replies. “Perhaps today though, I will.”

She takes a cigarette, and he lights both hers and his and places the ashtray next to her empty plate.

“So where shall we go first, then?” he asks, puffing smoke high into the ceiling.

“You’re assuming I want to go with you,” she says, frowning with mock severity.

“Ah no,” he exclaims immediately. “You prefer to be alone. I do understand.”

“Not necessarily,” she responds, grinning provocatively.

He realises she is teasing him and probably enjoying herself now. A burst of sunshine outside indicates that the day is becoming brighter. There are not so many people in the canteen now but those who remain are chattering noisily and cigarette smoke swirls in the air. He inhales smoke again as the sound of a radio and Vera Lynn singing can be heard filtering out from the kitchen to join the other sounds in the big room. The woman that cleared up the spilt tea approaches and begins collecting the empty crockery, putting it on her tray. She asks if she can get them anything else, but both shake their heads slowly, negatively. As she walks away Brian inclines his head towards her retreating form and suggests that she is probably feeling miffed because they are still there and not ordering anything else.

“There’s no rush for tables now,” Elsie says defiantly.

“No there isn’t. So, we will just finish our cigarettes in peace and tranquillity.”

“Tranquillity? Big word.”

They both laugh. Then Elsie reverts to silence, listening to the music from the radio. Soon she says that perhaps they had better think about moving before the next big rush commences.

Nothing unusual in a young man and a young woman walking along the streets of central London, talking away merrily and occasionally laughing. They seem as if they have known each other for a long time and nobody, surely, would guess that they only met an hour ago? The conversation may be lightweight, a discussion about where they each live and who they live with. That sort of thing. A few broad observations on the current weather they are experiencing and speculation about how and when it might dramatically change. They seem to take everything in their stride on their walk, noting but not commenting on the many sandbags that are now seen outside buildings.

It is only when they reach Piccadilly Circus that Elsie lets out a little exclamation of surprise.

“Oh, what happened to the statue of Eros, then?” Elsie wonders.

Brian is smiling broadly. “Covered him up to save him from enemy bombs.”

The statue is completely covered in panels and advertisement posters have been plastered round the visible parts. An American Army Air Force officer is standing right next to the covered Eros, calmly smoking a cigarette. Looking up to the top, Elsie can see no sign of the winged God. She frowns, says he’s gone and looks vexed.

“No, he’s still there,” Brian tells her. “He’ll be let out again, after the war.”

They continue their walk along Piccadilly. They are not talking quite so much now – perhaps they have run out of questions for each other. In Green Park, they find it curious that much of the parkland is deserted, although here and there they notice little groups of people, standing and talking in an animated fashion. As they begin to retrace their steps back to where they were, Elsie looks up to see a large silver barrage balloon hovering in the sky above. This in turn makes her wonder if there will be an air raid that evening.

“Clear, dry weather,” Brian is contemplating. “The conditions the Hun likes for bombing raids.”

In Coventry Street, they find they are quite thirsty again after their long walk. They go into a milk bar, and both consume a hot, sticky, milky drink that Brian speculates may well have strange and exotic ingredients. Continuing their walk, they find themselves in Leicester Square where Elsie had been earlier, passing the Empire and little Ritz cinemas. They stop at Brian’s request to look at the publicity pictures outside the Ritz. “Have you seen it?” Brian wants to know.

“No.”

“Would you like to?”

“Oh, er no, I don’t think so. Ticket prices are so high for this one.”

“Well, we could splash out for once,” he suggests. “I expect you like Clark Gable, like most of the girls.”

“Not really,” she replies. As an afterthought, she adds: “I quite like that nice Leslie Howard, though.”

He smiles and says there you are then. Why not? It would pass the time pleasantly and give their tired feet a welcome break. She reminds him that the film runs for over four hours, so they say, but he tells her he is not due back on camp until midnight. How about her? She has plenty of time, she informs him. So she nods her head in agreement, smiling and he says it will be his treat, but she won’t have that. She will agree to go in only if they go Dutch and each pay their own way. He agrees, reluctantly.

The woman in the ticket kiosk says that the film is running now but has only 10 minutes to go to the end. She nods to a small knot of people waiting just by the door and tells them they are waiting for the next complete performance. They decide to wait with them. It is busy again in the square with people on the move. Elsie and Brian stand behind the little knot of people waiting for the next performance and watch the people all around and the flow of traffic. An army munitions vehicle rumbles slowly by.

It is cosy and comfortable inside the Ritz cinema. They manage to secure seats near the back but in central positions, so they have a good, clear, undistorted view of the big screen. Elsie finds that she is really enjoying the film she has spent two years trying to avoid and convince herself that it is not worth the extra money asked for ticket prices. She is captivated by the handsome Leslie Howard and amused by the frivolous Vivian Leigh with her “fiddle de dee” and impressive Southern States American accent. An English actress too, imagine! She is moved when the camera pans slowly back to reveal the hundreds of wounded soldiers lying on the ground awaiting treatment after the Battle of Atlanta and instinctively, impulsively, reaches out and grabs Brian’s hand.

Brian smiles contentedly and when she pulls her hand away, awkwardly, he waits a few minutes, his eyes on the image of Clark Gable on the screen, in close- up, looking bemused and arrogant simultaneously, then slowly, gently puts his hand over Elsie’s. She does not pull her hand back this time. When they watch the bright, Technicolor burning of Atlanta, there is a hush in the crowded cinema.

In the interval, he buys her an ice cream, and they sit quietly discussing the salient points of the film so far. Then they watch the next two hours silently, in rapture as he takes hold of her hand gently and holds it firmly until the end. Later they will walk down to Lyon’s Corner House where they will buy a drink and a light snack. Again, she will insist on going 50-50. He will walk her to Leicester Square Underground station to catch her tube train home to Holloway. He will ask her if she is on the telephone at home, but she is not. Her mother says they can’t afford it. She will write down her name and address on a piece of paper she tears out from a small pocket notebook in her handbag. He says he will write to her. Before she goes into the station, he will plant a brief, light kiss on her cheek which will surprise and please her. She will walk into the station feeling her cheeks burning and she will not expect to see him ever again.

CHAPTERFOUR

LONDON, SUNDAY MARCH 12 1944

A North London street on Sunday morning. Dull, somewhat grey all around with a swirl of fog. The fog is lifting, though, dispersing slowly, curling upwards to a drab, overcast sky. It is a dry day, quite warm for the most part, with only the damp chill of the remaining fog patches to hinder. Always quiet on Sunday mornings, it seems quieter than usual on this greyish day. It is partly the lack of people in the street that makes the atmosphere seem so melancholic. That and the dull, grey brickwork of the buildings, the taped windows of the shops and offices. The dust from recent bombings that hangs in the air.

A trolleybus glides to a halt at the request stop and Elsie alights from the platform. She wears a beige coloured coat over her colourful dress because, when she got out of bed this morning, it was cold. Cold, damp, and dreary. And foggy. She walks along the road and turns left into a minor road that is still a main thoroughfare. Elsie moves along this road and then turns left into a quiet street with medium-sized Victorian houses in terraces. She notes the houses as she passes them. Most look as they always do but three houses down, on the right, is a house that looks oddly out of shape, distorted somehow. It is the house Elsie remembers her friend Julia telling her about; it was hit by incendiary bombs, and they had to get all the occupants out quickly. The fire brigade had arrived swiftly and put out the fires. Elsie reaches the house where Julia has her bed sitting room and rings the bell next to her tiny name panel.

She is greeted by Julia who opens the door, grins, and throws her arms around Elsie’s neck and kisses her. Elsie, embarrassed, struggles quickly free and asks her friend not to be so demonstrative.

“Why not?” her friend asks. “I haven’t seen you in weeks and weeks and I was just greeting you.”

“Well, greet me calmly and quietly next time,” Elsie instructs but she grins at her friend, and they go up the staircase to Julia’s bedsitting room. It is a large room, sparsely furnished but containing the essentials: a bed, currently pulled up and placed in a recess in the wall, two armchairs, a table and two dining chairs. Julia settles her friend down in an armchair and admonishes her for staying away so long. Friends should stay in close contact in wartime, she advises. You never know. Elsie nods agreement.

“It’s a cold morning,” Julia says cheerfully. “I’ll make you some coffee.”

Julia goes out of the room to a tiny, adjoining closet that functions as her kitchen. She prepares Camp coffee, pours it into two large mugs and returns. She sits down facing her friend. The two young women sit facing a two-bar electric fire that sends out heat to their legs. The room is large, though, with a high ceiling so most areas of it do not benefit from the heat thrown out. Their conversation follows the line it usually does when they meet up after an absence. What they have been doing, their parents, the war. Julia though, wants to know all about Elsie’s boyfriend, Brian.

“He’s fine, or so he says,” she replies sombrely. “He wrote last week about his mates in the front line, and one has been gravely wounded. But he is all right in himself.”

“Well, that’s all right, then.”

“No, it isn’t,” Elsie says becoming animated. “He lives in Birmingham and I’m here in London. We see so little of each other. He doesn’t get much leave and they are few and far between and we can only meet up in London for a short time before he heads off to Birmingham. Or when he comes back. We go to the cinema or for dinner, but we can never be alone. In private.”

Well, it isn’t easy. Julia understands that. She thinks that perhaps they should get a hotel room in town for an hour or two. Elsie scoffs and pulls a face. Go in without any luggage and without a ring on her finger? Then leave after an hour or so. And does Julia have any idea what that would cost in Central London?

The two friends lapse into silence and stare at the electric fire. Elsie sips her coffee and eats the biscuit that came with it. She looks at Julia. The girl has a heavier build than Elsie’s, although she’s not overweight. Well, nobody is these days with food shortages and rationing. She is pretty and not unattractive, though, but she wears such plain clothes and always dull, unimaginative colours. She likes cardigans and all sorts of chunky woollies and no fashionable shoes.

“What about you?” Elsie asks Julia.

“Me?”

“Yes, you. Any men on the horizon?”

“No,” Julia says vigorously. “I don’t go out with men, you know that. Just go to the munitions factory, to work. Anyway, we’re talking about you and your man.”

Elsie is puzzled. Her friend always wants to know all about her male friends, not that there have been many but never seems to have any herself. She knows of just two men that Julia has been out with and neither of them lasted more than a week. Julia is nothing if not persistent, though. She prods, pokes, and continually persists in trying to get Elsie to say how much she cares for Brian.

“I really don’t know is the honest answer,” Elsie responds, looking thoughtful. ‘I like him well enough, and I think he likes me. He’s always polite and seems to want to please me. I look forward to seeing him on the rare intervals we meet but I don’t spend all my time in between dreaming about him with misty eyes.”

She stops talking suddenly, looks at Julia but receives no support. Julia is still listening, waiting for the next revelation. Elsie starts to say that she is fond of him, she supposes, but is that enough?

“Not madly in love, then?”

“Good heavens, no,” Elsie says, then frowns and looks thoughtful. “I would know if I was, wouldn’t I?”

Julia grins. “Oh yes, you’d know, right enough.”