Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

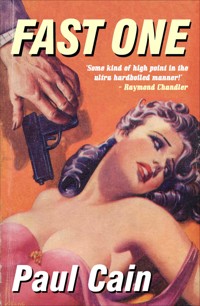

Fast One is possibly the toughest tough-guy and most brutal gangster story ever written. Set in Depression Los Angeles it has a surreal quality that is positively hypnotic. It is the saga of gunman-gambler Gerry Kells and his dipso lover S. Granquist (she has no first name), who rearrange the LA underworld and "disappear" in an explosive climax that matches their first appearance. The pace is incredible and relentless and the complex plot with its twists and turns defies summary. One Los Angeles reviewer called the book 'a ceaseless welter of bloodshed'; while the Saturday Review of Literature thought it 'the hardest-boiled yarn of a decade.' Fast One was originally a collection of stories featuring the gambler/gunman Kells. The tales ran in Black Mask magazine from 1931-1932

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 320

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Fast One is possibly the toughest tough-guy and most brutal gangster story ever written. Set in Depression Los Angeles it has a surreal quality that is positively hypnotic. It is the saga of gunman-gambler Gerry Kells and his dipso lover S Granquist (she has no first name), who rearrange the LA underworld and “disappear” in an explosive climax that matches their first appearance. The pace is incredible and relentless and the complex plot with its twists and turns defies summary. One Los Angeles reviewer called the book ‘a ceaseless welter of bloodshed’; while the Saturday Review of Literature thought it ‘the hardest-boiled yarn of a decade.’

Fast One was originally a collection of stories featuring the gambler/gunman Kells. The tales ran in Black Mask magazine from 1931-1932.

‘Paul Cain’ was the pseudonym George Carrol Sims, who also used the name Peter Ruric for his screenwriting work. He grew up on the rough streets of Chicago and claimed to have travelled extensively in his early life through central and South America, Europe and north Africa, but little concrete information is available about him apart from the fact that he dated Hollywood actress Gertrude Michael, upon whom the character of Granquist in Fast One is based.

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR Paul Cain’sFast One

‘…some kind of high point in the ultra hard-boiled manner.’ - Raymond Chandler

'Fast One is a swell steer; it is a dandy of a gangster story' - Paul Kane, newmysteryreader.com

Contents

Introduction

1 Chapter One

2 Chapter Two

3 Chapter Three

4 Chapter Four

5 Chapter Five

6 Chapter Six

7 Chapter Seven

8 Chapter Eight

Copyright

Introduction by

Max Décharné

Paul Cain's Fast One first appeared in the US in 1933, and then in a British edition in 1936. As debut novels go it's remarkable, but anyone holding their breath for the follow-up would have most likely been chewing their nails off in frustration - over seventy years later and there's still no sign of one. Impossible to summarise, Fast One is a lean, stripped-to-the-bone tale full of people who drink with both hands and throw money around like they print it fresh every morning just for kicks.

Hardly a household name in his heyday (or these days, come to think of it), the author seems to have led a life almost as shrouded in obscurity as that of some medieval scholar: quite an achievement, given that he lived mostly in LA at a time when it was dominating the world's media and had himself worked on many Hollywood movies.

So who was Paul Cain?

Well, his name wasn't really Cain; or Paul for that matter. Some people knew him as Peter Ruric, others as George Ruric. He seems to have arrived in the world as George Carrol Sims in Iowa in May 1902, but much of what he did between that date and his death in Los Angeles in 1966 is a matter of speculation.

Aged twenty three, the man who was later to become Paul Cain showed up in the heart of the Hollywood dream factory, calling himself George Ruric and working as a production assistant on Josef von Sternberg's 1925 silent film The Salvation Hunters, which features one Olaf Hytten as a character named simply 'The Brute'. Despite the picture's mixed audience reaction - memorably summed up in Richard Griffith and Arthur Meyer's phrase as 'even our lives are not so drab as this, and if they are we don't want to know about it' - the following year von Sternberg gave the public A Woman of the Sea, produced by Charlie Chaplin, with George Ruric listed as one of three assistant directors.

After this promising start in Tinseltown, the trail then goes cold, until the elusive Mr Sims emerges in the March 1932 issue of Black Mask magazine using the name Paul Cain, with a short story called Fast One. Black Mask was then under the command of its most famous editor, Joseph T Shaw. It had begun publishing in 1920, and was by this time already justly famous as the home of pioneering crime genre giants such as Dashiell Hammett and Carroll John Daly. Having broken through into the absolute top-drawer of monthly crime fiction writing, Paul Cain followed up by publishing a new story in each issue for the next six months - Lead Party (April 1932), Black (May 1932), Velvet (June 1932), Parlour Trick (July 1932), The Heat (August 1932) and The Dark (September 1932). Five stories from among these first seven - Fast One, Lead Party, Velvet, The Heat, The Dark - were joined together in 1933 to form Cain's only novel, which was published by Doubleday of New York under the title Fast One. Advance copies carried the following cover blurb:

You've read

THE MALTESE FALCON

GREEN ICE

LITTLE CAESAR

IRON MAN

hard, fast stories all, but now comes the hardest, toughest, swiftest novel of them all

FAST ONE

Two hours of sheer terror, written with a clipped violence, hypnotic in its power.

The author is

PAUL CAIN

These copies also came with a printed recommendation from another writer who was about to make his own entry into the field of crime fiction with a story in the December 1933 edition of Black Mask - a former oil executive and ex-public schoolboy named Raymond Chandler. In a phrase which has become the most famous comment about Cain's writing, Chandler called the novel 'some kind of high point in the ultra hard-boiled manner' and said that its ending was 'as murderous and at the same time poignant as anything in that manner that has ever been written.' It would be a further six years before his own debut novel, The Big Sleep, would make him internationally famous, but it's clear that even at the very start of his career Chandler's critical sense was right on the money.

Fast One must have been sold to the movies even before publication, because a film adaptation appeared the same year as the novel. However, the resulting effort, released under the title Gambling Ship, seems to have been put through the Hollywood mincer and emerged as an altogether different beast. Produced by Paramount, the film had the benefit of someone who became a major Hollywood name, but is not normally associated with hard-bitten tough-guy roles. Indeed, Cary Grant, who played Ace Corbin (the character based on Fast One's Gerry Kells), was more famously occupied that year trading wisecracks with Mae West in two of her biggest successes, I'm No Angel and She Done Him Wrong. Cain received a credit on the picture (as Peter Ruric) for providing the original story, but that seems to have been the extent of his involvement: the adaptation was by Claude Binyon, while Max Marcin and Seton I Miller wrote the screenplay. Two different people wound up with a director's credit, but it doesn't seem to have helped very much, and trade bible Variety called the finished result 'a fair flicker . . . but in toto it's a familiar formula of mob vs mob.'

For a while, Cain's crime writing career continued in the same high-profile fashion. Between the end of 1932 and 1936 he had a further ten stories published in Black Mask, plus the odd appearance in Star Detective Magazine and Detective Fiction Weekly, but after 1936 he seems to have abandoned fiction for good, partly because Joseph T Shaw was no longer editing Black Mask, but possibly also because his Hollywood scriptwriting career may have been proving more lucrative. For example, in 1934 he co-wrote the script for Edgar G Ulmer's classic Universal chiller The Black Cat - a defiantly over-the-top exercise in sustained menace starring Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. That same year he also co-scripted another film for Universal, The Affairs of a Gentleman, adapted from a play by Edith and Edward Ellis.

Still based in Hollywood, in 1937 he somehow became involved in the British film Jericho, a Paul Robeson vehicle partly shot in Cairo which also starred future Dad's Army stalwart John Laurie. Cain as Peter Ruric received co-writing credit with Robert N Lee (the scriptwriter of mob classic Little Caesar) for this unlikely tale of a US army deserter who flees across Africa having joined up with a native tribe.

1939 found him back in more familiar crime territory, co-writing the original story for a Lucille Ball film called Twelve Crowded Hours, and then in 1941 he adapted a hit Broadway murder mystery by Ayn Rand for the Paramount picture The Night of January 16th. 1942 brought what is often regarded as the most successful of the crime films in which he was involved, Grand Central Murder, an MGM picture starring Van Heflin which was adapted from a novel by Sue McVeigh about a killing in New York's famous railway terminal. Cain then moved from bodies in the booking office to classics of 19th century French literature with 1944's Guy de Maupassant adaptation, Madame Fifi, for producer Val Lewton, and then in 1948 came what appears to be his last film credit, the sentimental Wallace Beery star vehicle Almost a Gentleman.

After this Peter Ruric bows out of the Hollywood limelight, but Paul Cain had recently enjoyed something of a post-war resurrection when a collection of some of his old Black Mask stories was issued in book form under the title Seven Slayers in 1946. These were: Black (May 1932), Parlour Trick (July 1932), Red 71 (December 1932), One, Two, Three (May 1933), Murder In Blue (June 1933), Pigeon Blood (November 1933) and Pineapple (March 1936). It wasn't a follow-up novel to Fast One, but it was Cain's only other book, and as a collection of short, sharp hardboiled vignettes it has few equals.

George Carroll Sims died in Hollywood in 1966, having apparently worked in television for a while, and also written about food for Gourmet magazine. Fast One, his finest achievement, has until now been out of print for quite some time, and yet its status among crime connoisseurs has only increased with the years, and in September 2002 at Christies in New York an advance copy of the US first edition sold for $2,868, more than three times the estimate, while copies of the 1987 No Exit edition have reached $100 a throw on eBay.

As for the story itself, like Jack Carter in Ted Lewis's Jack's Return Home (aka Get Carter), or William Holden and his buddies in Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, Gerry Kells in Fast One is someone who's been pushed too far and will not take no for an answer, even if the consequences might prove dangerous.

"A few days ago - yesterday - all I wanted was to be let alone... I wasn't. I was getting along fine - quietly - legitimately - and Rose and you and all the rest of these ------ ------- gave me action." He stood up. "Alright - I'm beginning to like it."

That's the basic motor for whatever plot the novel has, although mostly it seems propelled more by the logic of dreams or nightmares. Throw in Kells' alcoholic girlfriend Granquist - 'Do you want a glass or a funnel?' - some corrupt politicians, a few double-crossing racketeers and a brace of out-of-town trigger men and you have a full-blown recipe for trouble.

You're after an uplifting story with a moral attached? Go somewhere else. The only possible lesson to be drawn here is that maybe standing next to a sharp operator is a dangerous place to be and that sometimes it pays to take your winnings and catch the Super Chief back east a day early.

More than that, it's mostly useless to say.

If there's a better hardboiled novel than Fast One out there, I'm still looking for it.

Max Décharné

Berlin, May 2004

Chapter One

KELLS walked north on Spring. At Fifth he turned west, walked two blocks, turned into a small cigar store. He nodded to the squat bald man behind the counter and went on through the ground-glass-paneled door into a large and bare back room.

The man sitting at a wide desk stood up, said, “Hello” heartily, went to another door and opened it, said: “Walk right in.”

Kells went into a very small room, partitioned off from the other by ground-glass-paneled walls. He sat down on a worn davenport against one wall, leaned back, folded his hands over his stomach, and looked at Jack Rose.

Rose sat behind a round green-topped table, his elbows on the table, his long chin propped upon one hand. He was a dark, almost too handsome young man who had started life as Jake Rosencrancz, of Brooklyn and Queens. He said: “Did you ever hear the story about the three bears?”

Kells nodded. He sat regarding Rose gravely and nodded his head slowly up and down.

Rose was smiling. “I thought you’d have heard that one.” He moved the fingers of one hand down to his ear and pulled violently at the lobe. “Now you tell one. Tell me the one about why you’ve got such a load on Kiosque in the fourth race.”

Kells smiled faintly, dreamily. He said: “You don’t think I’d have an inside that you’d overlooked, do you, Jakie?” He got up, stretched extravagantly and walked across the room to inspect a large map of Los Angeles County on the far wall.

Rose didn’t change his position, he sat staring vacantly at the davenport. “I can throw it to Bolero.”

Kells strolled back, stood beside the table. He looked at a small watch on the inside of his left wrist, said: “You might get a wire to the track, Jakie, but you couldn’t reach your Eastern connections in time.” He smiled with gentle irony. “Anyway, you’ve got the smartest book on the Coast – the smartest book west of the Mississippi, by God! You wouldn’t want to take any chances with that big Beverly Hills clientele, would you?”

He turned and walked back to the davenport, sank wearily down and again folded his hands over his stomach. “What’s it all about? I pick two juicy winners in a row and you squawk. What the hell do you care how many I pick? – the Syndicate’s out, not you.”

He slid sideways on the davenport until his head reached the armrest, pulled one long leg up to plant his foot on the seat and sprawled the other across the floor. He intently regarded a noisily spinning electric fan on a shelf in one corner. “You didn’t get me out in this heat to talk about horses.”

Rose wore a lightweight black felt hat. He pushed it back over his high bronzed forehead, took a cigaret out of a thin case on the table and lighted it. He said: “I’m going to reopen the Joanna D. – Doc Haardt and I are going to run it together – his boat, my bankroll.”

Kells said: “Uh huh.” He stared steadily at the electric fan, without movement or change of expression.

Rose cleared his throat, went on: “The Joanna used to be the only gambling barge on the Coast, but Fay moved in with the Eaglet, and then Max Hesse promoted a two-hundred-and-fifty-foot yacht and took the play away from both of them.” Rose paused to remove a fleck of cigaret paper from his lower lip. “About three months ago, Fay and Doc got together and chased Hesse. According to the story, one of the players left a box of candy on the Monte Carlo – that’s Hesse’s boat – and along about two in the morning it exploded. No one was hurt much, but it threw an awful scare into the customers and something was said about it being a bigger and better box next time, so Hesse took a powder up the coast. But maybe you’ve heard all this before.”

Kells looked at the fan, smiled slowly. He said: “Well – I heard it a little differently.”

“You would.” Rose mashed his cigaret out, went on: “Everything was okay for a couple weeks. The Joanna and Fay’s boat were anchored about four miles apart, and their launches were running to the same wharf; but they both had men at the gangways frisking everyone who went aboard – that wasn’t so good for business. Then somebody got past the protection on the Joanna and left another ticker. It damn near blew her in two; they beached, finally got into dry dock.”

Kells said: “Uh huh.”

“Tonight she goes out.” Rose took another cigaret from the thin case and rolled it gently between his hand and the green baize of the table.

Kells said: “What am I supposed to do about it?”

Rose pulled the loose tobacco out of one end of the cigaret, licked the paper. “Have you got a match?”

Kells shook his head slowly.

Rose said: “Tell Fay to lay off.”

Kells laughed – a long, high-pitched, sarcastic laugh.

“Ask him to lay off.”

“Run your own errands, Jakie," Kells swung up to sit, facing Rose. “For a young fella that’s supposed to be bright,” he said, “you have some pretty dumb ideas.”

“You’re a friend of Fay’s.”

“Sure,” Kells nodded elaborately. “Sure, I’m everybody’s friend. I’m the guy they write the pal songs about.” He stood up. “Is that all, Jakie?”

Rose said: “Come on out to the Joanna tonight.”

Kells grinned. “Cut it out. You know damn well I’d never buck a house. I’m not a gambler, anyway – I’m a playboy. Stop by the hotel sometime and look at my cups.”

“I mean come and look the layout over.” Rose stood up and smiled carefully. “I’ve put in five new wheels and – ”

“I’ve seen a wheel,” Kells said. “Make mine strawberry.” He turned, started toward the door.

Rose said: “I’ll give you a five-percent cut.”

Kells stopped, turned slowly, and came back to the table. “Cut on what?”

“The whole take, from now on.”

“What for?”

“Showing three or four times a week … Restoring confidence.”

Kells was watching him steadily. “Whose confidence, in what?”

“Aw, nuts. Let’s stop this god-damned foolishness and do some business.” Rose sat down, found a paper of matches and lighted his limp cigaret. “You’re supposed to be a good friend of Fay’s. Whether you are or not is none of my business. The point is that everyone thinks you are, and if you show on the boat once in a while it will look like everything is under control, like Fay and I have made a deal; see?”

Kells nodded. “Why don’t you make a deal?”

“I’ve been trying to reach Fay for a week.” Rose tugged at the lobe of his ear. “Hell! This coast is big enough for all of us; but he won’t see it. He’s sore. He thinks everybody’s trying to frame him.”

“Everybody probably is.” Kells put one hand on the table and leaned over to smile down at Rose. “Now I’ll tell you one, Jakie. You’d like to have me on the Joanna because I look like the highest-powered protection at this end of the country. You’d like to carry that eighteen-carat reputation of mine around with you so you could wave it and scare all the bad little boys away.”

Rose said: “All right, all right.”

The phone on the table buzzed. Rose picked up the receiver, said “Yes” three times into the mouthpiece, then “All right, dear,” hung up.

Kells went on: “Listen, Jakie. I don’t want any part of it. I always got along pretty well by myself, and I’ll keep on getting along pretty well by myself. Anyway, I wouldn’t show in a deal with Doc Haardt if he was sleeping with the mayor – I hate his guts, and I’d pine away if I didn’t think he hated mine.”

Rose made a meaningless gesture.

Kells had straightened up. He was examining the nail of his index-finger. “I came out here a few months ago with two grand and I’ve given it a pretty good ride. I’ve got a nice little joint at the Ambassador, with a built-in bar; I’ve got a swell bunch of telephone numbers and several thousand friends in the bank. It’s a lot more fun guessing the name of a pony than guessing what the name of the next stranger I’m supposed to have shot will be. I’m having a lot of fun. I don’t want any part of anything.”

Rose stood up. “Okay.”

Kells said: “So long, Jakie.” He turned and went through the door, out through the large room, through the cigar store to the street. He walked up to Seventh and got into a cab. When they passed the big clock on the Dyas corner it was twenty minutes past three.

*

THE DESK CLERK gave Kells several letters, and a message: Mr. Dave Perry called at 2:35, and again at 3:25. Asked that you call him or come to his home. Important.

Kells went to his room and put in a call to Perry. He mixed a drink and read the letters while a telephone operator called him twice to say the line was busy. When she called again, he said, “Let it go,” went down and got into another cab. He told the driver: “Corner of Cherokee and Hollywood Boulevard.”

Perry lived in a kind of penthouse on top of the Virginia Apartments. Kells climbed the narrow stair to the roof, knocked at the unsheathed fire door; he knocked again, then turned the knob, pushed the door open.

The room filled with crashing sound. Kells dropped on one knee, just inside, slammed the door shut. A strip of sunlight came in through two tall windows and yellowed the rug. Doc Haardt was lying on his back, half in, half out of the strip of sun. There was a round bluish mark on one side of his-throat, and, as Kells watched, it grew larger, red.

Ruth Perry sat on a low couch against one wall and looked at Haardt’s body. A door slammed some place toward the back of the house. Kells got up and turned the key in the door through which he had entered, crossed quickly and stood above the body.

Haardt had been a big loose-joweled Dutchman with a mouthful of gold. His dead face looked as if he were about to drawl: “Well … I’ll tell you …” A small automatic lay on the floor near his feet.

Ruth Perry stood up and started to scream. Kells put one hand on the back of her neck, the other over her mouth. She took a step forward, put her arms around his body. She looked up at him and he took his hand away from her mouth.

“Darling! I thought he was going to get you.” She spoke very rapidly. Her face was twisted with fear. “He was here an hour. He made Dave call you …”

Kells patted her cheek. “Who, baby?”

“I don’t know.” She was coming around. “A nance. A little guy with glasses.”

Kells inclined his head toward Haardt’s body, asked: “What about Doc?”

“He came up about two-thirty … Said he had to see you and didn’t want to go to the hotel. Dave called you and left word. Then about an hour ago that little son of a bitch walked in and told us all to sit down on the floor …”

Someone pounded heavily on the door.

They tiptoed across to a small, curtained archway that led to the dining room. Just inside the archway Dave Perry lay on his stomach.

Ruth Perry said: “The little guy slugged Dave when he made a pass for the phone, after he called you. He came to, a while ago, and the little guy let him have it again. What a boy!”

Someone pounded on the door again and the sound of loud voices came through faintly.

Kells said: “I’m a cinch for this one if they find me here. That’s what the plant was for.” He nodded toward the door. “Can they get around to the kitchen?”

“Not unless they go down and come up the fire escape. That’s the way our boy friend went.”

“I’ll go the other way.” Kells went swiftly to Haardt’s body, knelt and pick up the automatic. “I’ll take this along to make your story good. Stick to it, except the calls to me and the reason Doc was here.”

Ruth Perry nodded. Her eyes were shiny with excitement.

Kells said: “I’ll see what I can get on the pansy – and try to talk a little sense to the telephone girl at the hotel and the cab driver that hauled me here.”

The pounding on the door was almost continuous. Someone put a heavy shoulder to it, the hinges creaked.

Kells started toward the bedroom, then turned and came back. She tilted her mouth up to him and he kissed her. “Don’t let this lug husband of yours talk,” he said – jerked his head down at Dave Perry – “and maybe you’d better go into a swoon to alibi not answering the door. Let ‘em bust it in.”

“My God, Gerry! I’m too excited to faint.”

Kells kissed her again, lightly. He brought one arm up stiffly, swiftly from his side; the palm down, the fist loosely clinched. His knuckles smacked sharply against her chin. He caught her body in his arms, went into the living room and laid her gently on the floor. Then he took out his handkerchief, carefully wiped the little automatic, and put it on the floor midway between Haardt, Perry and Ruth Perry.

He went into the bedroom and into the adjoining bathroom. He raised the window and squeezed through to a narrow ledge. He was screened from the street by part of the building next door, and from the alley by a tree that spread over the back yard of the apartment house. A few feet along the ledge he felt with his foot for a steel rung, found it, swung down to the next, across a short space to the sill of an open corridor-window of the next-door building.

He walked down the corridor, down several flights of stairs and out a rear door of the building. Down a kind of alley he went, through a wooden gate into a bungalow court and through to Whitley and walked north.

*

CULLEN’S house was on the northeastern slope of Whitley Heights, a little way off Cahuenga. He answered the fourth ring, stood in the doorway blinking at Kells. “Well, stranger. Long time no see.”

Cullen was a heavily built man of about forty-five. He had a round pale face, a blue chin and blue-black hair. He was naked except for a pair of yellow silk pajama- trousers; a full-rigged ship was elaborately tattooed across his wide chest.

Kells said: “H’are ya, Willie,” went past Cullen into the room. He sat down in a deep leather chair, took off his Panama hat and ran his fingers through red, faintly graying hair.

Cullen went into the kitchen and came back with tall glasses, a bowl of ice and a squat bottle.

Kells said: “Well, Willie –”

Cullen held up his hand. “Wait. Don’t tell me. Make me guess.” He closed his eyes, went through the motions of mystic communion, then opened his eyes, sat down and poured two drinks. “You’re in another jam,” he said.

Kells twisted his mouth into a wholly mirthless smile, nodded. “You’re a genius, Willie.” He’ sipped his drink, leaned back.

Cullen sat down.

Kells said: “You know Max Hesse pretty well. You’ve been out to his house in Flintridge.”

“Sure.”

“Do you know what Dave Perry looks like?”

“No.”

Kells put his glass down. “A little patent-leather, pop-eyed guy with a waxed mustache. Wears gray silk shirts with tricky brocaded stripes. Used to run a string of trucks down from Frisco – had some kind of warehouse connection up there. Stood a bad rap on some forged Liberty Bonds about a year ago and went broke beating it. Married Grant Fay’s sister when he was on top.”

“I’ve seen her,” Cullen said. “Nice dish.”

“You’ve never seen Dave at Hesse’s?”

Cullen shook his head. “I don’t think so.”

“All right. It wouldn’t mean a hell of a lot, anyway.” Kells picked up his glass, drained it, stood up. “I want to use the phone.”

He dialed a number printed in large letters on the cover of the telephone book, asked for the Reporters’ Room. When the connection was made, he asked for Shep Beery, spoke evenly into the instrument: “Listen, Shep, this is Gerry. In a little while you’ll probably have some news for me … Yeah … Call Granite six five one six … And Shep – who copped in the fourth race at Juana? … Thanks, Shep. Got the number? … O K.”

Cullen was pouring drinks. “If all this is as bad as you’re making it look – you have a very trusting nature,” he observed.

Kells was dialing another number. He said, over his shoulder: “I win twenty-four hundred on Kiosque.”

“That’s fine.”

“Perry shot Doc Haardt to death about four o’clock.”

“That’s fine. Where were you?” Cullen was stirring his drink.

Kells jiggled the hook up and down. “Goddamn telephones,” he said. He dialed the number again, then turned his head to smile at Cullen. “I was here.”

The telephone clicked. Kells turned to it, asked: “Is Number Four on duty?” There was a momentary wait, then: “Hello, Stella? This is Mister Kells … Listen, Stella, there weren’t any calls for me between two and four today … I know it’s on the record, baby, but I want it off. Will you see what you can do about it? … Right away? … That’s fine. And Stella, the number I called about three-thirty – the one where the line was busy … Yes. That was Granite six five one six … Got it? … All right, kid, I’ll tell you all about it later. ‘Bye.”

Cullen said: “As I was saying – you have a very trusting nature.”

Kells was riffling the pages of a small blue address book. “One more,” he said, mostly to himself. He spun the dial again. “Hello – Yellow? Ambassador stand, please … Hello. Is Fifty-eight in? … That’s the little bald-headed Mick, isn’t it? … No, no: Mick … Sure … Send him to two eight nine Iris Circle when he gets in … Two … eight … nine … That’s in Hollywood; off Cahuenga …”

They sat for several minutes without speaking. Kells sipped at his drink and stared out of the window. Then he said: “I’m not putting on an act for you, Willie. I don’t know how to tell it; it doesn’t make much sense, yet.” He smiled lazily at Cullen. “Are you good at riddles?”

“Terrible.”

The phone rang. Cullen got up to answer it. Kells said: “Maybe that’s the answer.” Cullen called him to the phone. He said, “Yes, Shep,” and was silent a little while. Then he said, “Thanks,” hung up and went back to the deep leather chair. “I guess maybe we can’t play it the way I’d figured,” he said. “There’s a tag out for me.”

Cullen said slowly, sarcastically: “My pal! They’ll trace the phony call that your girl friend Stella’s handling, or get to the cab driver before he gets to you. We’ll have a couple carloads of law here in about fifteen minutes.”

“That’s all right, Willie. You can talk to ‘em.” Cullen grinned mirthlessly. “I haven’t spoken to a copper for four years.”

Kells straightened in his chair. “Listen. Doc went to Perry’s to see me … What for? I was with Jack Rose being propositioned to come in with him and Doc, on the Joanna. They’re evidently figuring Fay or Hesse to make things tough and wanted me for a flash.” He looked at his watch. Cullen was stirring ice into another drink.

Kells went on, swiftly: “When I open the door at Perry’s, somebody lets Doc have it and goes out through the kitchen. Maybe. The back door slammed but it might have been the draft when I opened the front door. Dave is cold with an egg over his ear and Ruth Perry says that a little queen with glasses shot Doc and sapped Dave when he spoke out of turn …”

Cullen said: “You’re not making this up as you go along, are you?”

Kells paid no attention to Cullen’s interruption. “The rod is on the floor. I tell Ruth to stick to her story... Cullen raised one eyebrow, smiled faintly with his lips. Kells said: “She will,” went on: "… and try to keep Dave quiet while I figure an alibi, try to find out what it’s all about. I smack her to make it look good and then I get the bright idea that if I leave the gun there they’ll hold both of them, no matter what story they tell. They’d have to hold somebody; Doc had a lot of friends downtown.”

Kells finished his drink, picked up his hat and put it on. “I figured Ruth to office Dave that I was working on it and that he might keep his mouth shut if he wasn’t in on the plant.” Cullen sighed heavily.

Kells said: “He was. Shep tells me that Dave says I had an argument with Doc, shot him, and clipped Dave when he tried to stop me. Shep can’t get a line on Ruth’s story, but I’ll lay six, two, and even that she’s still telling the one about the little guy.” He stood up. “They’re both being held incommunicado. And here’s one for the book: Reilly made the pinch. Now what the hell was Reilly doing out here if it wasn’t tipped?”

Cullen said: “It’s a set-up. It was the girl.” ,

Kells shook his head slowly. “Dave knows it and is trying to cover for her.” ,

Cullen went on. “She told you a fast one about the little guy and I’ll bet she’s telling the same story as Dave right now.”

“Wrong.”

Cullen laughed. “If you didn’t think it was possible you wouldn’t look that way.”

“You’re crazy. If she wanted to frame me she wouldn’t’ve put on that act. She wouldn’t’ve …”

“Oh, yes, she would. She’d let you go and put the finger on you from a distance.” Cullen scratched his side, under the arm, yawned.

Kells said: “What about Dave?”

“Maybe Doc socked Dave.”

“She’d cheer.”

“Maybe.” Cullen got up and walked to a window. “Maybe she cheered and squeezed the heater at the same time. That’s been done, you know.”

Kells shook his head. “I don’t see it,” he said. “There are too many other angles.”

“You wouldn’t see it.” Cullen turned from the window, grinned. “You don’t know anything about feminine psychology –”

Kells said: “I invented it.”

Cullen spread his mouth into a wide thin line, nodded ponderously. “Sure,” he said, “there are a lot of boys sitting up in Quentin counting their fingers who invented it too.” He walked to the stair and back. “Anyway, you had a pretty good hunch when you left Exhibit A on the floor.”

“I’m superstitious. I haven’t carried a gun for over a year,” Kells smiled a little.

Cullen said: “Another angle – she’s Fay’s sister.”

“That’s swell, but it doesn’t mean anything.”

“It might.” Cullen yawned again extravagantly, scratched his arms.

Kells asked: “Yen?”

“Uh huh. I was about to cook up a couple loads when you busted in with all this heavy drama.” Cullen jerked his head toward the stair. “Eileen is upstairs.”

Kells said: “I thought the last cure took.”

“Sure. It took.” Cullen smiled sleepily. “Like the other nine. I’m down to two, three pipes each other day.”

They looked at one another expressionlessly for a little while.

A car chugged up the short curving slope below the front door, stopped. Kells turned and went into the semidarkness of the kitchen. A buzzer whirred. Cullen went to the front door, opened it, said: “Come in.” A little Irishman in the uniform of a cab driver came into the room and took off his hat. Cullen went back to the chair and sat down with his back to the room, picked up his drink.

The phone rang.

Kells came out of the kitchen and answered it. He stood for a while staring vacantly at the cab driver, then said, “Thanks, kid,” hung up, put his hand in his pocket and took out a small neatly folded sheaf of bills. “When you brought me here from the hotel about four o’clock,” he said, “I forgot to tip you.” He peeled off two bills and held them toward the driver.

The little man came forward, took the bills and examined them. One was a hundred, the other a fifty. “Do I have to tell it in court?” he asked.

Kells smiled, shook his head. “You probably won’t have to tell it anywhere.”

The driver said: “Thank you very much, sir.” He went to the door and put on his hat.

Kells said: “Wait a minute.” He spoke to Cullen: “Can I use your heap, Willie?”

Cullen nodded without enthusiasm, without turning his head.

Kells turned to the driver. “All right, Paddy. You’d better stall for an hour or so. Then if anyone asks you anything, you can tell ‘em you picked me up here – on this last trip – and hauled me down to Malibu. No house number – just the gas station, or something.”

The driver said, “Right,” went out.

“Our high-pressure police department finally got around to Stella.” Kells went back to his chair, sat down on the edge of it and grinned cheerfully at Cullen. “How much cash have you got, Willie?” Cullen gazed tragically at the ceiling.

“It was too late to catch the bank,” Kells went on, “and it’s a cinch I can’t get within a mile of it in the morning. They’ll have it loaded.”

“I get a break. I’ve only got about thirty dollars.”

Kells laughed. “You’d better keep that for cigarets. I’ve got to square this thing pronto and it’ll probably take better than change – or maybe I’ll take a little trip.” He got up, walked across the room and studied his long white face in a mirror. He leaned forward, rubbed two fingers of one hand lightly over his chin. “I wonder if I’d like Mexico.”

Cullen didn’t say anything.

Kells turned from the mirror. “I guess I’ll have to take a chance on reaching Rose and picking up my twenty-four C’s.”

Cullen said: “That’ll be a lot of fun.”

THE FIRST STREET lights and electric signs were being turned on when Kells parked on Fourth Street between Broadway and Hill. He walked up Hill to Fifth, turned into a corner building, climbed stairs to the third floor and walked down the corridor to a window on the Fifth Street side. He stood there for several minutes intently watching the passersby on the sidewalk across the street. Then he went back to the car.

As he pressed the starter, a young chubby-faced patrolman came across the street and put one foot on the running board, one hand on top of the door. “Don’t you know you can’t park here between four and six?” he said.