9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

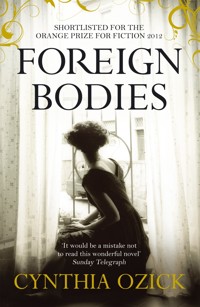

Shortlisted for the Orange Prize for Fiction 2012, Foreign Bodies is a dazzling and profound exploration of the human face of the central relationship in the last century: that between the old world and the new. The collapse of her brief marriage has stalled Bea Nightingale's life, leaving her middle-aged and alone, teaching in an impoverished borough of 1950s New York. A plea from her estranged brother gives Bea the excuse to escape lassitude by leaving for Paris to retrieve a nephew she barely knows; but the siren call of Europe threatens to deafen Bea to the dangers of entangling herself in the lives of her brother's family. By one of America's great living writers, Foreign Bodies is a truly virtuosic novel. The story of Bea's travails on the continent is a fierce and heartbreaking insight into the curious nature of love: how it can be commanded and abused; earned and cherished; or even lost altogether.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

FOREIGN BODIES

Fiction by Cynthia Ozick:

Dictation Heir to the Glimmering World The Puttermesser Papers The Shawl The Messiah of Stockholm The Cannibal Galaxy Levitation: Five Fictions Bloodshed and Three Novellas The Pagan Rabbi and Other Stories Trust

FOREIGN BODIES

CYNTHIA OZICK

First published in the United States in 2010 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, New York.

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Cynthia Ozick, 2010

The moral right of Cynthia Ozick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 84887 735 1 Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 362 8 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 583 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd. Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

But there are two quite distinct things—given the wonderful place he’s in—that may have happened to him. One is that he may have got brutalized. The other is that he may have got refined.

—Henry James, The Ambassadors

FOREIGN BODIES

I

July 23, 1952

Dear Marvin,

Well, I’m back. London was all right, Paris was terrible, and I never made it down to Rome. They say it’s the hottest summer they’ve had since before the war. And except for the weather, I’m afraid there’s not much else to report. The address you gave me — Julian left there about a week ago. It seems I just missed him by a few days. You wouldn’t have approved, a rooming house in a rundown neighborhood way out toward the edge of the city. I did the best I could to track him down — tried all the places you said he might be working at. His landlady when I inquired turned out to be a pure blank. All she had to offer was an inkling of a girlfriend. He took everything with him, apparently not much.

I’m returning your check. From the looks of where your son was living, he could certainly have used the $500. Sorry I couldn’t help more. I hope you and (especially) Margaret are well.

Yours,

Beatrice

2

IN THE EARLY FIFTIES of the last century, a ferocious heat wave assaulted Europe. It choked its way north from Sicily, where it scorched half the island to brownish rust, up toward Malmö at the lowest tip of Sweden; but it burned most savagely over the city of Paris. Hot steam hissed from the wet rings left by wine glasses on the steel tables of outdoor cafés. In the sky just overhead, a blast furnace exhaled searing gusts, or else a fiery geyser, loosed from the sun’s core, hurled down boiling lava on roofs and pavements. People made this comparison and that — sometimes it was the furnace, sometimes the geyser, and now and then the terrible heat was said to be a general malignancy, a remnant of the recent war, as if the continent itself had been turned into a region of hell.

At that time there were foreigners all over Paris, suffering together with the native population, wiping the trickling sweat from their collarbones, complaining equally of feeling suffocated; but otherwise they had nothing in common with the Parisians or, for that matter, with one another. These strangers fell into two parties — one vigorous, ambitious, cheerful, and given to drink, the other pale, quarrelsome, forlorn: a squad of volatile maundering ghosts.

The first was looking to summon the past: it was a kind of self-intoxicated theater. They were mostly young Americans in their twenties and thirties who called themselves “expatriates,” though they were little more than literary tourists on a long visit, besotted with legends of Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. They gathered in the cafés to gossip and slander and savor the old tales of the lost generation, and to scorn what they had left behind. They rotated lovers of either sex and played at existentialism and founded avant-garde journals in which they published one another and bragged of having sighted Sartre at the Deux Magots, and were proudly, relentlessly, unremittingly conscious of their youth. Unlike that earlier band of expatriates, who had grown up and gone home, these intended to stay young in Paris forever. They made up a little city of shining white foreheads; but their teeth were stained from too much whiskey and wine, and too many powerful French cigarettes. They spoke only American. Their French was bad.

The other foreign contingent — the ghosts — were polyglot. They chattered in dozens of languages. Out of their mouths spilled all the cadences of Europe. Unlike the Americans, they shunned the past, and were free of any taint of nostalgia or folklore or idyllic renewal. They were Europeans whom Europe had set upon; they wore Europe’s tattoo. You could not say of them, as you surely would of the Americans, that they were a postwar wave. They were not postwar. Though they had washed up in Paris, the war was still in them. They were the displaced, the temporary and the temporizing. Paris was a way station; they were in Paris only to depart from Paris, as soon as they knew who would have them. Paris was a city to wait in. It was a city to get away from.

Beatrice Nightingale belonged to neither party. She had been “Miss Nightingale” — in public — for twenty-four years, even during her marriage and certainly after the divorce, and had sometimes begun to think of herself by that name, if only to avoid the accusatory inward buzz of Bea. To Bea or not to Bea: she was one of that ludicrously recognizable breed of middle-aged teachers who save up for a longed-for summer vacation in the more romantic capitals of Europe. That these capitals, after the war, were scarred and exhausted, drained of all their well-advertised enchantments, did not escape her. She was resilient, intelligent, not inexperienced (marriage itself had taught her a thing or two). She was, after all, forty-eight years old, graying only a little, and tough with her students, high school boys sporting duck-tail haircuts who laughed at Wordsworth and ridiculed Keats: when they came to “Ode to a Nightingale” they went out of their way to hoot and leer — but she knew how to tame them. She was good at her job and not ashamed of it. And after two decades at it, she was not yet burned out.

She had signed up for London, Paris, and Rome, but gave up on Rome (even though it was included in the agent’s package deal) when she read, in her noisy hot hotel room off Piccadilly, of the dangerous temperatures in the south. London had been nearly bearable, if you kept to the shade, but Paris was hideous, and Rome was bound to be an inferno. “That ludicrously recognizable breed” — these were her mocking words to herself (traveling alone, she had no one else to say them to), though likely parroted from some jaunty guidebook, the kind that makes light of its own constituents. A more conscientious guidebook, the one sequestered at the bottom of her capacious bag — passport, notepad, camera, tissues, aspirin, and so on — was not jaunty. It was punishingly painstaking, and if you were obedient to its almost sacerdotal cartography, you would come away exalted by pictures and sculptures and historic public squares redolent of ancient beheadings.

On this July day the page she was consulting in her guidebook was bare of Monets and Gauguins and day-trip chateaus. It was captioned “Neighborhood Cafés.” All afternoon she had been walking from café to café, searching for her nephew. A filmy smear greased her vision — it was as if her corneas were melting — and her heartbeat either ran too fast or else meant to run out altogether, with small reminding jabs. The pavements, the walls of buildings, blew out torrid vibrations. Paris was sub-Saharan, she was being cooked in a great equatorial vat. She fell into a wicker chair at a burning round table and ordered cold juice, and sat panting, only half recovered, with her blurry eye on the garçon who brought it. Her nephew was a waiter in one of these sidewalk establishments, this much she knew. It was difficult to think of him as her nephew: he was her brother’s son, he was too remote, he was as uncertain for her as a rumor. Marvin had sent her a photograph: a boy in his twenties, straw hair, indeterminate expression. How to sort him out from the identical others, with their wine-spattered white aprons tied around their skinny waists? She supposed she could spot him once he opened his mouth and revealed himself as an American: she had only to say to any probable straw-haired boy, Excuse me, are you Julian?

— Pardon?

— I’m looking for Julian Nachtigall, from California. Do you know him, does he work here?

— Pardon?

— Un Américain. Julian. Un garçon. Est-il ici?

— Non, madame.

Doubtless there was a more efficient way of finding him. Marvin had written out, in those big imperious letters as loud as his big imperious voice, his son’s precise address. Three times, so far, she had climbed the broken front steps of the squat brown house in the broken brown neighborhood her fastidious guidebook mentioned only to warn its readers away. A bony landlady erupted from a door at the top of the stoop; the boy, she said in a garble as broken as her teeth, lived overhead, one flight up, only no, he was not home, he was not home already four days. Oui, certainement, he worked in one of the cafés, what else was a boy like that good for? At least she got the rent out of him. Dieu merci, he has a rich father over there.

So! A wild goose chase, useless, pointless, it was eating into her vacation time, and all to please Marvin, to serve Marvin, who — after years of disapproval, of repudiation, of what felt almost like hatred — was all at once appealing to the claims of family. This fruitless search, and the murderous heat. Retrograde Europe, where you had to ask bluntly for a toilet whenever you wanted a ladies’ room, and where it seemed that nothing, nothing was air-conditioned — at home in New York, everything was air-conditioned, it was the middle of the twentieth century, for God’s sake! Her guidebook showed no concern for the tourist’s bladder, and in its fervid preoccupation with the heirlooms of the ages never dreamed of cooling off. It recommended small quaint boutiques in fashionable neighborhoods — if you cared for something American-style, it chided, stay in America. But she had had enough of the small and the quaint and the unaffordably fashionable, and more than enough of that asinine wandering from café to café: what she needed was air-conditioning and a toilet, and urgently. She walked on through the roasting miasma of late afternoon, and when she saw before her a tall gray edifice with a frieze incised above its two stately doors, for a moment she supposed it was yet another historic site smacking of Richelieu. But there were letters in the stone: GRAND MAGASIN LUXOR. A department store! The cold air came rushing at her with its familiar saving breath. The ladies’ room was very much like what she might have found in, say, Bloomingdale’s, all mirrors and marble sinks. Call it American-style, condemn it for its barbarous mimicry, Louis XIII on the outside, New York on the inside — the place was life-giving.

The ladies’ room led out through a corridor into something like a restaurant, though it resembled more a busy Broadway cafeteria, where shoppers sat surrounded by their newly purchased bags and boxes. The ceiling was misty with smoke; all these people were intent on their cigarettes. She looked around for a seat. Every table was taken. Then she noticed an empty spot strewn with ash-filled saucers, occupied by three noisy men and a woman.

She put her hand on the back of the vacant chair. “Will it be all right if I settle down here for a minute?”

The woman gave out a help-yourself-what-do-I-care shrug. It was impossible to know whether she understood English, or whether the gesture with the chair was enough. The men continued what seemed to be an argument. Here there was no heap of overflowing bags: presumably this intense little circle, like Bea herself, had no local purpose other than refuge from the griddle of the streets. Odors of eggs and coffee all around. Floating tongues of perfume: a mannequin sailing by, uncannily tall, feet uncannily long, a trail of silky garments over one long arm, breastless, eyes of glass, Matisse-red mouth, perfection of jaw and limbs and stiffened hair, the very model of a Parisian model, exuding streams of fragrance. The men stared, as if sighting a yellow tiger in a place that smelled of kitchen. “Imbéciles,” the woman muttered; these syllables, addressed to Bea, were roughened by an unidentifiable accent. The accent matched the woman’s hard look: tight black curls sprouting from an angry head. The visionary living robot slid away, and the men resumed their quarrel — if it was a quarrel. Their talk was French and not-French, it had the sound of half a dozen languages all at once: Europe scrambled. A quarrel, a protest, a lament, a bark of resignation? Bea sank into the clear relief of sitting still and shedding warmth — she could almost fall asleep against these enigmatic contentious voices, wavering like underwater flora at the far rim of her fatigue. The deadly walk back to the hotel still ahead. These people, who were they, where did they come from? Too shabby, too provisional, to be ordinary citizens. They didn’t belong, they were out of place and out of sorts. They hung their cigarettes from their lower lips only to let the time pass. The woman, with those impatient furious whorls springing up around a blotched face, stood up and was pulled down by one of the men. She stood up again, to go where? Where had they come from, where could they go?

Bea left them finally. She had seen their like strewn all over Paris.

She went one last time to find Marvin’s son. The jagged-toothed landlady materialized as before, only now in cotton house slippers, with a wet mop in hand and a big rag wound round her waist. She was washing down the stairs. The boy was gone, since two days gone for good with his knapsack and a girl to help drag out the duffle bag. What did he have in there, iron bars? The room was his for one week more, it was a blessing anyhow that he owed nothing, that useless boy, because of the father in America. The girl? A quiet little dark thing, like an Arab or a gypsy.

— How should I know where he went? He didn’t tell me, why should he?

— I need to talk to him, I’m his aunt.

— I’m sorry for you, a boy like that. My own two nephews, they have real jobs, not one day here, one day there, a different boss every time. Maybe he moved in with her, that one, not a kid like him, already a wrinkle between the eyes, that’s what they do, after a while they move in with them. If you want to take a look upstairs, I don’t object, only watch the steps, they’re still wet. I looked in up there myself, to see about damage. A couple of nails in the wall, I don’t mind, like if he hung a picture.

— Well, but did he leave anything behind?

— I found this up there, if you want it it’s yours, it’s no use to me.

The landlady held out a battered book.

In the taxi going back to her hotel, she examined it. Something like a dictionary, an indecipherable language across from a column of French, not a name inscribed, not a sign of anything. It was old; the pages were brittle and loose. Pointless to keep it, so when she paid the driver and got out, she abandoned it.

The next day she visited the Louvre, and for the rest of the week — as far as her money and the lethal weather allowed — she relied on her guidebook to lead her to storied scenes and ancient glories. Then she went home to her two-and-a-half-room apartment on West 89th Street, where the bulky shoulder of an air conditioner darkened a window and vibrated like a worn drum. And where to Bea or not to Bea was always the question.

3

July 28, 1952

Dear Bea,

You missed him? You were right there in Paris, you knew exactly where he was, you knew reasonably well where he might be employed, and I depended on you. And what do I get instead? A weather report! The business as you know has me pretty much tied up lately, I couldn’t for love or money get out there myself, my sister takes a vacation and thinks of nothing but her own pleasure and leaves me in the dark. You simply didn’t try hard enough. I realize you don’t know Julian, but if you haven’t got any family feeling, why not a little family responsibility?

You mention a girl. As if in passing. Julian is twenty-three years old. At this age to get himself mixed up with some girl over there is not what I have in mind for my son. You understand that Margaret would go if it was feasible, but as you are aware she is somewhat neurasthenic, and is plainly incapable of traveling alone. Of course we are both very distressed, Margaret even more than I. She finds it intolerable that we sometimes don’t know Julian’s whereabouts, he writes so infrequently. I recognize that he’s at that experimental stage typical of his generation, they want to try out this and try out that, and if it’s a little on the spiteful side, all the better, they go for it. The trouble with these kids is that they haven’t had the military to toughen them up, not that I’m not glad he’s been spared what I saw in the Pacific. And considering that I got through it as an overaged LCDR it wasn’t so easy for me either. A headstrong boy, I suppose we’ve indulged him. Or maybe not — there’s nothing out of the ordinary with junior year abroad, they all do it nowadays. One year with the Paris meshugas, all right, but it’s been three, and he shows no signs of returning to finish up. I can assure you that Margaret and I never anticipated a dropout! As an alumnus who’s made substantial contributions to my alma mater, I’m embarrassed. There was no hint of his not finishing, even with all that crazy reading he was doing, Camus and whatnot, a waste of time for a science major. Or history of science, the soft stuff, he doesn’t have a head for the real thing. Iris is the one, she takes after me, a commonsensical head on her shoulders, and a good head for chemistry too — halfway through a doctorate, in fact. I expect her to marry intelligently. You can never tell how genes ricochet, I sometimes think there’s a bit of you in Julian, and God knows I can’t have him ending up in a bad marriage, not to mention teaching louts on their way to the body shop.

As far as the 500 bucks are concerned, you imply this was to get him out of that slum into something better. Not so! I can imagine what sort of grimy getup he’s been running around in, and I did speak of cleaning him up with something respectable, a shirt and an actual suit, etc., whatever the cost, but I told you explicitly, I want my son out of there altogether, out of Europe, out of the bloody dirt of that place, and back home in America where he belongs. He complains that his mother and I manipulate him — whatever he thinks that means — yet if anyone’s doing the manipulating, it’s Julian. I hear from him only when his pockets are past empty. Otherwise the few times he writes it’s to Iris. They used to be close, those two, as thick as thieves, though with the three years between them and his head in the clouds they never had much in common that I could see.

But if anyone can dope out what he might be up to, it’s his sister. Who knows what he tells her — she reads his letters and then they disappear. If you ask her she says he’s fine, he’s well, he’s attending some sort of lecture thing, he’s got some sort of job — it turns out he’s wiping up tables.

Now here’s my idea, and this time I hope you’ll come through. As soon as we get wind of where he’s at, I want you to take a week or so and go over there again and bring him back. I don’t care how you do it. Do whatever you do when you get your body shop guys to swallow those nursery rhymes you keep shoving down their throats. You seem to think you’re good at that. If you have to bribe him — I mean with $$$ — then bribe him. Just get him back to New York, for starters. He won’t be willing to come out here to his own family, at least not right away. I suspect he’ll be too hang-dog. There’s Iris who always has her little cat-that-ate-the-canary smile, and there’s Julian, the sullen one, and what’s he got to sulk about? He’s always had his own way. When you get off the plane at Idlewild, I want you to take him home with you and keep him for a couple of days and calm him down. I don’t say he won’t be resentful, but if you can handle your regular louts, you can handle a boy like Julian. Talk books to him — he’ll like that.

But that’s only part of my idea. It’s not that I think it’ll be a cinch to pry him out of Paris. He’s wormed his way into the life over there — Iris says he sometimes even writes to her partly in French. I’m not so stupid as to believe that a relative he’s never met, who comes at him out of the blue, is going to be much of an influence, just like that. You have to know him, to figure him out, not that I’ve been able to. I can’t reach him, that’s the fact of it, and Margaret — Margaret’s awfully tired. Some days she’s just too tired to cope with the thought of Julian, how long he’s been away.

So Iris is the one. I’m sending her east next week, to get you acquainted with Julian. A briefing, in navy lingo. I should have arranged something like this before you went off on that vacation — but then I found out about it too late to do anything except get the check to you. You ought to be in touch more. When I see how thick Iris is with Julian, I realize how derelict my own sister’s been. Ever since mama and papa died, eighteen years since mama, ten since papa, what do I know of your life? That you had a bad patch with a fellow who played the oboe, or whatever it was? Iris’s plane is due at LaGuardia Thursday afternoon at 4:10 P.M. She’ll stay the weekend, and then it’s back on Monday — she’s got her 9 A.M. lab Tuesday morning.

As ever,

Marvin

July 31, 1952

Dear Marvin,

I am looking forward to meeting your daughter. Luckily I have no out-of-town plans as I sometimes do on weekends in the summer, and will be free to host her. I believe she was no more than two or so, the only time I ever saw her. It’s very fine that Iris understands Julian so well — she would certainly make a better emissary than I, so why not? I’m afraid you are being a little high-handed when you suppose I can simply fly off again at a word from you. I do have a job, whether or not you esteem it.

Yrs, Bea

August 3, 1952

Bea:

Don’t tell me about your so-called job, they’ll never miss you. You do what you do and you are what you are because you never had the drive to be anything else. Iris is on her way to a Ph.D., I told you this, the hard stuff, the real thing — she’s an ambitious kid, she’s on track, she sticks to what she starts. It’s you I want over there, I’ve explained why. You can make the time — get yourself one of those substitutes from the teachers’ union or whatever. As I said, I’ll let you know where Julian’s at as soon as we hear. Meanwhile Iris will fill you in.

Marvin

4

MARVIN’SRANT, Marvin’s bluster, with all its contradictions and lame exposures. The brutishness of his language, even when he imagined himself at his fanciest. The old nasty condescension. An unwitting confession of desperation — his son was a hard case, that was the long and the short of it. And still he intended, with a wave of a seigneurial hand, to ship her out again.

Marvin aimed high. How happy he would have been, Bea told Mrs. Bienenfeld, who taught history (this was during lunch break, in the teachers’ lounge), to have been sired by a Bourbon, or even a Borgia. A Lowell or an Eliot would have done nearly as well. Unfortunately, he was the grandson of Leib Nachtigall, an impoverished greenhorn from an impoverished village in Minsk Province, White Russia. Poor Marvin was unrelated to the Czar of All the Russias — unless he was willing to cite a certain negative connection: grandfather Leib had fled the Czar’s conscription, arriving in steerage and landing in Castle Garden with nothing but a tattered leather bag to start life in the New World. Marvin, miraculous Marvin, was the miraculous work of miraculous America. By now he was a dedicated Californian. And the greatest wonder of all was that he was a Tory (a Republican, in fact), an American Bourbon, an American Borgia! Or, if you insisted on going lower in the scale, a Lowell or an Eliot. If you did insist on going lower — just a little — you would discover that he had married a Breckinridge, the sister of a Princeton classmate. Her blood was satisfyingly blue. She had relatives in the State Department.

New York rarely drew him — an infrequent business trip; the two funerals, nearly a decade apart, first for mother, then for father. Bea had never set eyes on Marvin’s son. She had seen Iris, the older child, only once, on the sole occasion Marvin brought his wife and their little girl east, for a landmark class reunion. Iris and Julian: Bea could barely remember their names. When Julian was born she dispatched a present; it was politely acknowledged by Marvin’s wife: “Many thanks for your good wishes, and surely little Julian will enjoy the delightful giraffe” — something of the sort, on thick perfumed letter paper with that preposterous crest at the upper left margin.

Yet Marvin kept the ancestral name, and Bea, in deference to her students, had not: what were those big rough boys, with their New York larynxes, to make of Nachtigall? What they made of it was a cawing, a gargling, a sneezing, until she surrendered — though Nightingale had its own farcical consequences. Miss Mary Canary. Miss Polly-Want-a-Cracker. Miss Old Crow. Miss Robin Redbreast — that one produced smirks and snorts and whistles, and a clandestine blackboard sketch of a fat bird wearing eyeglasses and flaunting a pair of ballooning protuberances. As a penalty she ordered the smirkers to memorize “To a Skylark,” and tested them on their performance. Oh, what she had come to! Poetry as punishment. Wasn’t the summer’s trip to have been an antidote to all that, an earned indulgence?

“But can you imagine,” she said to Mrs. Bienenfeld, “he’s pushing me to go back, when I’ve just come home. He snaps his fingers and expects me to jump. As if I don’t have a life —”

That letterhead! Out of raw California, an aggrandizing crest — a silver shield displaying a pair of crossed swords rising out of a green river. A tribute to Margaret’s signal line: Marvin had found it in a book of Scottish heraldry.

5

THE AIR-CONDITIONING was on everywhere, rattling as always. It was eight o’clock. They had eaten supper on trays in the living room, where the machine ran cooler — poached eggs on toast. There was a pitcher of iced tea on a side table.

“Is it this hot in L.A.?” Bea asked.

“Mostly. Sometimes hotter. What was it like in Paris?”

“Worse. Horrible. Fainting-hot.”

“Did you actually faint?”

“No, but I drank gallons. The hotel people said it was the worst summer they’d had in fifteen years. Are you worn out from the plane, or would you like to take a walk? There’s still plenty of light. I can show you famous upper Broadway.”

“I’d rather sit here with you,” Iris said.

“We don’t have to get down to business right away. There’s tomorrow, and the two days after.”

“Business? Oh . . . about Julian.”

“What you’ve come for.”

“What dad says I’ve come for.” She stretched her neck to take in everything around her. “How long have you lived alone?”

Intrusive, impertinent!

Bea said, suppressing annoyance, “Nearly all my adult life.”

“I guess I sort of knew that. I heard you were married once.”

“Then your father’s had me on his mind a lot more than I would have thought —”

“Dad mentioned it a long time ago. I remember it because he almost never talks about his family.”

“Does your mother talk about hers?”

“Not really. But she can’t help it, people talk to her about them. Especially about my uncle who died. You know he was in Congress, he was even thinking of running for president.”

“So the papers said at the time.”

“I never knew him either.”

The girl had a way of flicking her hair out of her eyes with a shrug that was half twitch and half shudder. Yet there was nothing unsure in this. A sign of boldness rather: the shake of an impatient colt. Her hair was long, neither light nor dark — a kind of bronze. Metallic, and when she whipped it round it had, faintly, the sound of coins caught in a net. Her resemblance to her mother hinted at some indistinct old photograph, insofar as Bea could conjure up her faded impression of Margaret. Iris had the same opalescent skin — fragile white smoke, and the thin nose with its small ovoid nostrils, and the pale irises. Iris: had they named her for the human eye? Hers was more bland than vivid — a screen. She might look out at you, but you couldn’t fathom what stirred behind it.

“I thought while you’re here,” Bea said, “you might enjoy seeing a play. I’ve got us some tickets — a little theater down in the Village. Would you like that?”

It was self-defense. What did Marvin expect when he thrust his daughter at her? A walk, a play, sightseeing, what was she to do with this self-possessed young woman? The Empire State Building, views of the city? How to fill the time, how long would it take to be made privy to Julian’s habits, Julian’s predicament . . . Julian’s soul? And to what end?

“Those two days,” Iris said. “Well, I don’t have them anyhow.”

“But I understood from your father . . . you won’t be staying till Monday?”

“I’m leaving tomorrow. I’m sorry about the tickets, if they have to go to waste —”

Bea said, “Tomorrow?”

“Yes, and if you wouldn’t mind phoning dad, I know you usually write, but he won’t care if you call him long-distance collect. Especially if it’s urgent. Just explain that you want to keep me the whole week, and by Friday I’ll be back.”

Bea took a bewildered breath. “Back from where?”

“From seeing Julian. It’s all set, plane fare and everything, but only if you help. If dad found out he’d blow up.”

“Your father told me you have to be back at school, that’s one thing,” Bea said. “And the other is you can’t possibly go off to Paris all on your own —”

But it came to her that she had herself hinted exactly this to Marvin: Iris as envoy.

“I’ve got the fare and practically the whole rest of it left over. In traveler’s checks. The money dad gave me to give you for the rescue operation, bring ’im back alive.”

“You don’t know where he is.”

“Mom and dad don’t know. There’s been a letter, only not for them, for me. I sneaked it past them, I always do that, they never saw it. Part of it nobody can read anyhow, it isn’t even French, it’s in a weird sort of writing, one of Julian’s jokes — he’s a funny boy sometimes.”

“I won’t go along with this,” Bea said. “I can’t let you, your father sent you here, you can’t just run off —”

“I’m not twelve years old, and you don’t want to go. You told dad you have to teach, you can’t leave.”