7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Galley Beggar Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

FRANCIS PLUG is back. The lovable misfit is now adjusting to life as a newly published author. Interviews and publicity are coming his way, not to mention considerable acclaim. But Francis can't understand why people think he was writing fiction... He also has plenty of other problems – and very little money. Fortunately, he's handed a lifeline when he lands a job as Writer-in-Residence at the University of Greenwich. Unfortunately, this involves interacting with more new people, which isn't exactly Francis's strong suit. Try as he might, the staff and students at the university seem to have great difficulty knowing what to make of Francis. (Not to mention the trouble that he has making sense of himself...). Oh – and now he also needs to hook in some big-name authors for the Greenwich Book Festival, and has to write his own campus novel. The urgent questions build and build – and Francis is in no state to answer them Will he keep his job? Will he be able to secretly sleep inside a university office? Will anyone find out that he did a wee in the corridor? ... Find out as Francis embarks on a new adventure, more intoxicating and hilarious than ever.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

FRANCIS PLUG

Writer in Residence

PAUL EWEN

For Violet & Vincent

‘That I have not got a thousand friends, and a place in England among the esteemed, is entirely my own fault. The door to “success” has been held open to me. The social ladder has been put ready for me to climb… Yet here I am, nowhere, as it were, and infinitely an outsider. And of my own choice.’

D.H. LAWRENCE

‘Drunk and with dreams I’m lost out at sea.’

ANGEL OLSEN, ‘Drunk and with dreams’

CONTENTS

The entrance doors to the BBC’s Broadcasting House open inwards, like in scary children’s stories. The two receptionists are men, one of whom is speaking into a phone, like a Telethon volunteer. I inform his colleague that I’m here to see Sarah Johnson.

Receptionist: Francis Plug?

FP: Yes. Do you know me?

Receptionist: No.

FP: Darn.

Receptionist: You’re very early.

FP: Ah, yes. The thing is, I need a bit of time, you see. To sober up.

My visitor’s pass is encased within a plastic pouch. All passes are to be displayed prominently, so I pin mine to the middle of my chest, like a circuit board on a Doctor Who character. A foyer sign declares that staff and visitors may have their bags and persons searched upon exiting the building. They should get someone from The Bill to do that, or perhaps Noddy’s friend, Mr Plod. But it looks like they’ve signed up unknowns for the task. What a shame. They’ve really missed a trick there.

My reception seat faces the entrance doors. Despite many comings and goings, there’s no sign of any famous people. A woman sits nearby reading her phone. She doesn’t ring any bells, but maybe she’s a star in the making.

FP: Are you here for the Sherlock job?

Woman: Sorry?

FP: Are you here for the Sherlock job?

Woman: No.

FP: Monty Python?

Woman: No.

FP: Teletubbies?

Woman: No.

FP: Some Mothers Do ’Ave ’Em?

Woman: No.

FP: Morph?

Woman: No.

FP: Crimewatch?

Woman: Sorry, I need to do something, okay?

The drinks are already wearing off, even though I’ve come directly from the Yorkshire Grey. Being a Samuel Smith’s pub, the Yorkshire Grey has no TVs or radios blaring out. There’s also a policy of no advertising or promotional material in-house, so the refined surroundings lack the shouty-ness of other pubs. The BBC appeals for similar reasons. Of course, that’ll all change when I’m on air, wanging on about my book.

If you’re being broadcast to the nation, and beyond, it’s best that you balance your alcohol intake in the run-up. Doing an ‘Oliver Reed’ is not ideal, but nor is the other extreme: arriving in tatters, a nervous quivering wreck. It’s all about calculating the equilibrium. Too wonky either side and you’ll end up skew-whiff. My pre-interview drinks had to be methodically thought through, therefore, like a Formula One team considering the track surface and weather conditions. I didn’t want to ram full-tilt into a fence, but nor did I wish to stall the engine on the starting grid.

It’s easy to see how overnight success and fame can be overwhelming. Unable to cope, many are steered off the straight and narrow path, turning to drugs or drink. Of course, some of us new arrivals are off this path already, so we kind of bump back on briefly, careering wildly, before veering off the opposite side.

Samira Ahmed is interviewing me on Radio 4, for the Front Row arts programme. It’s a pretty big deal. As an emerging author, it’s important to grasp any such prospect with both hands. Given nearly 200,000 books are published each year in the UK alone, there’s a lot of pressure to stand out. To squander a chance, such as a BBC interview, due to some ill-thought action or behaviour, would be most careless. All those other authors out there wouldn’t thank me. If I encounter them later, at some literary event or such-like, they may prove less than cordial.

Fellow Author: Francis Plug? What a prick.

Sarah Johnson is a producer for Radio 4. She called me the other day with some questions which, I gathered, were to help Samira Ahmed ask her questions. But I suspect it was also an opportunity to assess my broadcast abilities, to get a heads up, prior to the recording, in case I spoke like Sasquatch. However, just because I didn’t snort and gibber down the phone doesn’t mean I’m fit for broadcast. Desperation isn’t always something you can hear. Without visual cues, like twitching, fidgety eyes, soiled clothing, or a subservient, demeaning posture, such a judgment is ultimately uninformed. Rancid, petrol-smoked breath and sour, unwashed skin can only present themselves in person.

Although I didn’t swear on the phone, I’ll have to mind that too. Coarse language is something I used to keep in check, but now, as a result of my circumstances, I’ve let it slip. This unpicked thread of beery words can be traced back to a letter of eviction for my flat, and the subsequent repossessing of my van and gardening tools, which stripped me of my livelihood and primary means of income. There have also been some unrelated legal issues and threats to contend with, and the small matter of living under fir trees for a time, or hiding overnight inside pubs. Perhaps any screw-ups can be bleeped out, or replaced with another audio bite from the BBC’s extensive archive, such as a Big Ben toll, or a Thunderbirds launch, or a howler monkey.

When Sarah Johnson arrives to collect me, I’m ticking off a list of things that I hope to see, for real, during my BBC visit.

FP: Weather presenting stick. Zippy’s zip-mouth earring. Songs of Praise candle…

Sarah Johnson: Hi Francis, I’m Sarah.

FP: Hi Sarah.

Sarah Johnson: Have you come far?

FP: No, I’m in West Hampstead at the moment.

Sarah Johnson: Oh yes.

FP: As opposed to Hampstead Village. I haven’t caught the gravy train just yet. I haven’t started wearing a suit jacket without a tie.

Sarah Johnson: No, sure. West Hampstead’s a quick trip on the Tube, isn’t it? Jubilee line to Bond Street?

FP: Actually, I got the bus. The 139. It heads straight down Abbey Road, over the zebra crossing outside the studios.

Sarah Johnson: Of course, the zebra crossing.

FP: Yes. I always imagine the 139’s brakes failing, and we career down Abbey Road, taking out all of the Beatles. Splat! And that would be the end of all that.

Sarah Johnson: Mm. Well, thankfully you’re a few decades late.

FP: There’s still Paul and Ringo. The worst ones.

A set of revolving doors leads from the foyer into the depths of the building itself. These are patrolled by a security guard, but, disappointingly, it’s not Ronnie Barker in his Porridge uniform. Sarah Johnson beeps a turnstile with her staff pass so we can progress further, before beeping the lift into action. Inside, important people are talking earnestly, but they aren’t famous important people. Sarah chats separately with me as we journey upwards. Most of the TV studios, she says, are based in the newer U-shaped wing of the building, whereas I’ll be in the old bit, with the radio crowd. That’s a shame, I think. What could possibly be worth seeing for real in a radio studio? Soundproofing foam? Hollowed-out coconut shells used for making clippity-clop horse noises? I begin ticking a new list off on my fingers. The lift is very slow.

Sarah Johnson: Have you done any radio work before, Francis?

FP: No. But when I was little I used to listen to Spike Milligan’s story Badjelly the Witch. That was on the radio all the time.

Sarah Johnson: Was it? I don’t think I know that one.

FP: It’s when Tim and Rose go looking for their cow Lucy, who’s been kidnapped by a witch, called Badjelly. She tries to poke God’s eyes out.

Sarah Johnson: The witch does?

FP: Correct.

The other people in the lift have stopped talking and are now looking at the ceiling.

FP: And Badjelly the witch is always screaming KNICKERS, KNICKERS! STINKY-POO, STINKY-POO!

Sarah Johnson: Ah, here we are.

There are more pass-operated doors to beep, and a myriad of hallways and turns as we delve deeper into the BBC’s house. They have plenty of spare bedrooms by the look of it, many of which have soundproofing on the walls, which would be good insulation in winter.

FP: How many toilets are there in this house?

Sarah Johnson: In Broadcasting House? I really couldn’t tell you.

FP: More than Buckingham Palace?

Sarah Johnson: Probably…

FP: They have seventy-eight. Seventy-eight throne rooms.

Sarah Johnson: Do you need the toilet, before we start?

FP: Better safe than sorry, right?

When I’m done, hands washed and dried, we proceed into another long corridor. Two women wait further ahead. One of these, I learn, is a sound engineer called Jeneal, and the other is my interviewer, Samira Ahmed. Like Sarah Johnson, they are most welcoming and do their best to put me at ease. No doubt they’re used to dealing with famous authors, and since my novel is a thinly veiled self-help guide, alluding to fears of public speaking and social encounters in general, they are extra vigilant. Sarah Johnson magics up a plastic cup of water before directing me to my seat in the studio. She and Jeneal adjourn to the control room next door, where they’re visible through a large window. It’s like looking at them in space, from the deck of the Enterprise, except they’re the ones behind the controls, and I’m the floating one, lacking oxygen. Samira Ahmed and myself are on either side of a large round table. From it sprout a dozen or so protruding microphones, each with a different coloured foam top. Mine is green.

FP: Ha! It’s like Zoot’s nose!

Samira Ahmed: Zoot?

FP: The saxophone player in The Muppets. Even though he’s blue, he has a green foamy nose.

Samira Ahmed: I see.

FP: Fozzie Bear has brown hairy fur, but his nose is pink. And Floyd Pepper, the bass player, is purple but his nose is orange.

Samira Ahmed: Interesting. The Muppets crop up in your book, don’t they? When you’re at the Arundhati Roy event and you’re wondering which Muppet says ‘Five seconds till curtain’.

FP: How did you know that?

Samira Ahmed: It’s in your book.

FP: What, you’ve actually read my book?

Samira Ahmed: Yes, of course.

FP: Shit a brick!

Jeneal, it transpires, has used our Muppet chat to do a sound level check. Samira Ahmed suggests I read a passage from my book, and we can use this as a conversation starter. A pre-selected passage has already been typed up and printed onto a single sheet of paper. Some authors recommend reading your own work aloud as part of the writing process. This, they believe, helps with the rhythm and flow of the text. Personally, I feel a bit silly reciting my written words aloud, particularly since I tend to write in the sort of pubs where spoken word verse hasn’t really caught on. Attempting to voice it now, into Zoot’s nose, is friggin’ embarrassing. It’s like getting up in front of the class to read what you did in the holidays, except the class has 60 million people in it, not even counting BBC World Service, which probably runs into the billions. On top of that, I certainly don’t remember my holiday journals being so confusing and poorly written.

FP: Whoah. This must have been closing time stuff. Seriously.

Samira Ahmed: Do you want to try again, from the top?

FP: Okay. But maybe you should all just turn away. Talk amongst yourselves…

While I attempt to read my own book, three members of BBC personnel must wait, their time funded from the pockets of the unsuspecting British public. Through my headphones comes Sarah Johnson’s voice. Because, on top of everything else, I have to wear blimmin’ great headphones.

Sarah Johnson: Francis? Listen, it’s fine. Don’t worry, we can get an actor in to record that, not a problem. We do that a lot.

FP: I can hear the sea. Can you? Can anyone else hear the sea?

Front Row is an arts magazine show that aims to enlighten listeners by probing those in the arts world about their work. Unfortunately, I don’t have any answers. My book, and the processes behind it, are every bit as baffling to me as they are to the next guy. My responses therefore begin as guesses, before inflating into minor untruths, and ultimately elements of fiction themselves. That is, when I remember what the question was.

Samira Ahmed: Sorry, you were talking to George Orwell?

FP: Yes, at the bar of the Boston Arms, in Tufnell Park. And he said, ‘Wow, you so have to write that. You’ll totally smash it.’

Samira Ahmed: But… didn’t he die in back in the 1950s?

FP: [Pause.] Maybe it wasn’t the Boston Arms. He used to work here at the BBC, didn’t he? Not the Boston Arms. No, it was the Yorkshire Grey…

My fidgeting doesn’t help. Apparently I’ve been tapping my nails on my visitor’s badge, squeezing my plastic cup in and out, and kicking the metal legs of my chair. In a sensitive audio environment like this, it’s not just your sweary words you need to mind. Simple physical movements can end up sounding like a hand dryer in a cuckoo clock factory during the Blitz. Just as well that control room window is soundproofed. They’re probably calling me all manner of oaths.

When Ian McEwan was on Front Row a few weeks ago, I tuned in, to try and learn from his mistakes. But he had everything buttoned down and sewn up. In fact, he was even correcting his interviewer, and laying down the law. He’s clearly an old hand at these things, with fourteen novels under his belt, and his work has even been adapted by the BBC itself. In comparison, as a debut novelist, I’m hardly in any position to throw my weight around. Although possibly sitting in the same chair as Ian McEwan, it’s hard enough for me simply not to break noisy wind as a result of my poor diet.

Samira Ahmed: … isn’t it? How do you feel about that, in relation to your own work?

FP: Um… I think… it would make a ripper show on the BBC, wouldn’t it? Who would I talk to about that…?

Fortunately, this isn’t going out live. So all the stuff-ups and the really stupid stuff can be edited out later, sifted from the minor stuff-ups and less stupid stuff. At least it’s only radio. At least I’ll only sound like a complete tool.

Samira Ahmed: Let’s stop there, shall we?

Removing the foamy green microphone cover, I affix it to my nose.

FP: What a friggin’ Muppet.

As Sarah Johnson escorts me back through the maze of Broadcasting House, every beeped door represents a certain goal reached, like a new stage in a Super Mario game. My interview, Sarah Johnson explains, will be broadcast later this evening, some six hours from now. Enough time, I say, to dig a decent hole, and to sit in that hole, with grass fronds and flax as covering.

Sarah Johnson: I suppose. If you get a hurry on.

As we turnstile back into the reception area, David Attenborough makes a low-key entrance through the main doors. As BBC stars go, he’s top of the crop. His career, spanning over sixty years, has been legendary. He is, in fact, the legendary man. He’s also a longtime supporter of the BBC, recently praising them and their support of the Natural History Department. The key to the BBC’s success, he claims, is its public ownership, which forces it to maintain the highest of standards. Although a national institution, the BBC has been under threat from the present government, who want to slash its budgets as part of their controversial austerity measures. If they had their way, the BBC’s two male receptionists would be replaced by one woman, in a pretty frock. And instead of self-opening entrance doors, there would be heavy, old-fashioned ones that you’d have to open yourself, even if you had no arms or legs.

FP: Hello, David Attenborough.

David Attenborough: Hello.

FP: I’ve just been in for an interview, on Radio 4. About my new book.

David Attenborough: Oh.

FP: Here, I’ve got a spare copy, let me sign it for you.

David Attenborough: Sorry, what was your name?

FP: Francis Plug. ‘To David Attenborough’ okay?

David Attenborough: Okay, I am in a bit of a rush…

FP: To David Attenborough…

The book-signing task, I’m finding, is a task indeed. Especially the personal dedications. Straight signature copies, for bookshops, is a blind, impersonal job carried out at pace, as if one were a seismograph during a short, violent earthquake. But personal dedications are different. They require real human contact between myself and a poised, living person, with specific expectations. Even process-driven remarks, such as ‘All the best’ or ‘Best wishes’, are potential traps, as I found out at my own book launch.

Man: ‘With worm regards’?

FP: Sorry?

Man: You wrote ‘With worm regards’.

FP: Ah, yes.

Man: Could you maybe just correct it? Turn the ‘o’ into an ‘a’?

FP: You don’t want my worm regards?

Man: Um…?

FP: Lovely worms. With their soil fertilizing. Worm regards to you, sir.

Signing a book for a man who has communicated with forest tribes, gorillas, and members of the royal family obviously requires some special acknowledgement. David Attenborough is standing right there, and he’s in a hurry, so I have to think fast on my feet. But I can’t. I can’t think. I’ve just had my brain fried, and now I’m pulling into the pits with no petrol, four flat tyres, and billowing smoke.

FP: Sorry, this is embarrassing…

David Attenborough: It’s all right, don’t worry about it.

FP: No, I am a writer, I know how to write things. I just don’t know… I’m not used to writing with other people around. It’s a bit like getting undressed at the beach, beneath your wet towel…

David Attenborough: Honestly, you needn’t worry.

FP: No, no, no. I’ve started so I’ll finish. That’s from a BBC programme, isn’t it?

I live by myself in a garage designed for one car. As a residence, it doesn’t quite equate with certain perceived ideas regarding my new literary standing. There’s the overriding dampness for one thing, mixed with the ingrained whiff of car oil. The insulation is very poor, the natural light non-existent. And the nightly run of skittery rats really doesn’t measure up to the success that my BBC interview might suggest. The garage door isn’t even automatic.

My lodging is one of thirty-four conjoined garages, laid out like beach huts behind a stretch of West Hampstead shops. Access is via an alleyway off the high street, allowing vehicle passage, including one man’s noisy Porsche, which lives next door. All the wooden doors are painted green, though the shades vary greatly, depending on their upkeep. At night they can’t be left open even a smidgen due to bleeding thievers. Having no exterior padlock, my door is a regular target, appearing easy prey. But at the first sound of these light-fingered tinkerers, I am quick to lay down the law.

FP: [Shouting.] FEE FI FO FUM!!

West Hampstead doesn’t have the literary glamour of its more famous villagey neighbour, but it’s nice enough. And although living in a garage, I have actually been published. It might not pay that well, but I’m not eating the rats. Free rent certainly helps. My former gardening clients, the Hargreaves, too old to drive their Bentley and being privy to my literary aspirations, offered me their garage as a writing studio. Given I was between homes at the time, the ‘writing studio’ became a lodging instead. As a home, it obviously lacks many of the usual comforts. Upon awakening, for instance, I am forced to wee at length into a peach tin. The heating isn’t brilliant either. At present, in late October, it’s like a breeze-block fridge. Holes in the doors, as well as being rat paths, also enable nippy drafts. A fan heater wouldn’t go amiss. Perhaps I’ll put the word out at my next author event.

It’s mid-morning and although shut inside my garage, I’m in no danger of being asphyxiated by the enveloping fumes. Because the fumes in question contain malt and barley and are presently being expelled, rather than inhaled. Unusually, my phone rings, surprising me with its distinctive Hit Me with Your Rhythm Stick ringtone. It’s Sam, my co-publisher. He has a couple of ‘interesting prospects’ to discuss. Firstly, Waterstones’ Piccadilly bookshop would like me to attend their Christmas signing event, as a featured author. There’ll be free mulled wine. All I have to do is sit around and maybe sign some books.

FP: Let me just see if I’m free that evening yes I’m free.

Also, more importantly, Sam wishes to discuss a prospective job. An actual means of regular employment. The University of Greenwich are looking for an inaugural Writer in Residence.

Sam: It’s a paid position. Not much, but… Elly and I thought you might be interested?

FP: A paid job? As a writer?

Sam: Yes. We’re not sure exactly what the role would entail, but essentially you’d need to start producing a significant work, such as another novel.

FP: You mean write? They would actually pay me to write?

Sam: Yes.

FP: Ha, ha! When do I start? I can move in today if need be.

Sam: Well, you wouldn’t actually live there, at the university. But you’d probably get a desk, maybe even an office. Of course, you’d need to apply for the role first, Francis. And if you’re lucky, get interviewed…

FP: I can start whenever, I’m really flexible. Tomorrow? If it helps, I can start tomorrow. Just a little desk is fine. It doesn’t need to be made from arbutus wood, like Edna O’Brien’s.

As small independent publishers, Sam and Elly can’t afford to pay me much. But they’ve tried their best to find me money from other outlets, such as editorial pieces, or online stuff. When my novel first arrived at their Norwich house from the printers, they paid for me to come up on the train and fed me lunch, and drinks, as I signed 100 copies at their dining table.

FP: Wow. I could stay here forever.

Sam: Ha, ha! You better not miss that train!

Thanks to Elly and Sam, copies of my book found their way to reviewers, and it met with some minor acclaim. It didn’t win the Booker Prize though, which was an absolute travesty. I think it was. Still, as I say, it has had some success. This has bewildered many of the local pub regulars. As one chap noted, they were surprised I could even read. But having seen the reviews I waved about unabashedly, they now think I’m minted. On the day of my BBC interview, I stupidly told all the pub staff and patrons to tune in. As it happened, no one ‘could be arsed’. But they still insisted I purchase drinks for the entire pub. In retrospect, I should have applied the Little Red Hen’s ‘loaf of bread’ model to my drinks round, because I still haven’t paid that tab back, and probably never will. Since then I’ve been less vocal about my writerly status, although I haven’t been able to shake my nickname.

Pub Patron 1: There he is. It’s Gideon.

Pub Patron 2: Gideon? Why do you call him that?

Pub Patron 1: Because his book is everywhere, supposedly, but no one with any fucking sense wants to read it.

The copy I presented to the pub, to be displayed behind the bar, quickly disappeared. When I enquired after it, Ed the landlord said they’d used the cover to start the fire, and the inside pages were being used for arse wiping in the staff toilets.

FP: Mind you don’t block your pipes. It’s good quality paper.

Ed: No, you’re wrong. Chapters one to ten are disintegrating in Beckton sewerage treatment works as we speak.

FP: I hope you didn’t wipe your poo on the title page. I wrote a special dedication on that, remember?

Ed: Did you? I added my own signature to it, I’m afraid.

Upon publication, I received ten complimentary copies of my book. It was tempting to sell them all on the Internet, signed first editions, to the highest bidders. But I ended up giving them away, to people I was anxious to impress. My parents, for one, and also my sister Claire. For Anna, my niece, I added a personalized hand-drawn etching of Julian Barnes’ severed head. A copy was set aside for the Hargreaves, with thanks for my ‘studio’, and copy number five was posted to Mr Stapleton, another former gardening client who’s involved with the Booker Prize (what a waste of postage that was). A further copy was chewed by rats, so I dropped that into a St Vincent de Paul shop, explaining to the volunteer that despite its condition, it was signed by the author and therefore immensely valuable. A dedicated copy was sacrificed to the pub, as mentioned, and I drunkenly gave another away to someone in the Czech & Slovak Bar & Restaurant, because they looked a bit like Kafka. David Attenborough secured my final spare copy, which leaves just the one edition for any future author events, despite its obvious signs of damp.

If I’d had my sensible shoes on, I would have invested my publishing advance in gardening equipment, to further my primary career. Instead, it all went on drink and cartons of cigarettes. Still, pubs make good offices, being warm, full of desks, and offering soap and mirror facilities. Tidy hair and hygiene are givens for the respected public figure, so I also pay occasional visits to Swiss Cottage Leisure Centre, making use of left-behind shampoos. Seeing my ungainly wet flesh could be traumatic for my readers, but if they’re anything like the average author event attendees, they probably swim in deeper waters than me.

Besides aiding cleanliness, pubs are where I write, honing my craft. At present, this involves formulating ideas for the next book. One thought I’m currently chucking about concerns a family who live in a shoe. But it’s not the latest trainer, so they’re sad. The drinks themselves, while not of a fruit variant, help to get the juices flowing. They’re also very useful, as discussed, for surviving the public side of the job.

Novels aren’t the only things I write in pubs. I also write ads, for myself, to put on the pub noticeboard.

Experienced residential gardener for hire. Currently without tools or van. If you have the tools, he’s the gardener. Competitive rates.

When I last checked, none of the little tear-offs at the bottom of the page were taken, although someone had written across the top:

THIS GUY DOESN’T NEED TOOLS. HE IS ONE!

Replacing the notice, I include an additional contact number, for my agent.

My agent has an office on the edge of Bloomsbury with impressive views across London. It’s a very desirable address. Not that she lives there. She may sleep in a one-car garage for all I know, but somehow I really don’t think so. As I pace around the reception area waiting for my agent’s assistant to collect me, coins fall out of my trouser pockets, spilling onto the floor.

Agent’s Assistant: What are you doing down there, Francis?

FP: I’ve got holes in my pockets.

Agent’s Assistant: Oh dear. Can I get you a drink?

FP: Yes, please. Two glasses of sherry, any kind.

My agent’s office has various books displayed on stands, like in a bookshop. These represent her victories, the manuscripts she has sold on for publication. It took quite a while for my own book to find success. None of the big publishers would touch it with a barge pole.

Agent: The general comment seems to be: ‘We just don’t know what to do with it.’

FP: Perhaps they could publish it, as a book, and sell it?

There was another problem. Many of the publishers remembered a particular Booker Prize ceremony, which I, as an unpublished author, had attended. According to some of those present, I’d made a bad impression. It wasn’t that bad. Okay, so I nearly died, but no one else did.

Eventually a very small publisher took a punt. Small, as in two people. Although a newish venture, Elly and Sam had already garnered acclaim by publishing certain top-notch books that the large, established publishers had chosen to disregard. Perversely, the huge, corporate publishers with the deepest pockets tend to be the tightest and most risk-averse, while for small publishers like mine, each book is literally sink or swim. Still, at least the little folk retain their integrity. Despite suffering sleepless nights fraught with financial worries, at least they can sleep well at night.

FP: … At least they’re not morally bankrupt, greedy-guts…

Agent: Now, now Francis. You don’t want to burn any more bridges. So… what was all this about David Beckham?

On West Hampstead High Street, I noticed a bus shelter advert for a whisky brand, which was fronted by the footballer David Beckham.

FP: David Beckham? Fronting whisky? Come on! He’s the golden boy of healthy sports. The nice lad with heaps of kids and charity training camps and really straight royal family mates. The pretty face, the safe pair of hands. If anyone should be advertising whisky, it’s me. Whisky and I have a genuine, honest association. That whisky brand needs to sign me up, quick smart.

Agent: Yes, but David Beckham’s a football star. A fashion model. You’re a minor, first-time novelist. Who, to be fair, doesn’t photograph well.

FP: But… but he probably drinks protein shakes. I drink whisky. I should be the face of whisky, even if it’s not a pretty one. And there might be freebies. How do we get the ball rolling on this?

Agent: Uh, Francis…

FP: Also, how do I get an assistant, who brings people drinks?

After reaching a stalemate on my global whisky ambassador prospects, I stand and prepare to leave. As I do, coins run out of my pockets, down my legs, onto the plush carpet.

FP: Not again!

Agent: You want to get yourself a coin pouch.

FP: A what?

Agent: A coin pouch. A small leather wallet thing you keep your coins in.

FP: That sounds like just the ticket. Do they have them at the Pound Shop?

Agent: The Pound Shop? I wouldn’t know. Try Liberty’s.

Being an author isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Most emerging writers, like myself, need a second trade, unless they’re inheritors of significant wealth. Even established mid-list authors are struggling these days, competing against the latest literary trend or ‘hit’. Books may be perceived as important in England, home of Eliot, Austen, Shakespeare and Dickens, but as the author of one, I don’t feel all that special. Unlike other professions, there’s no pension plan or health benefits. Most festivals and appearance slots are unpaid, even though the majority of attendees probably park their cars in the sort of place I live. Perhaps we’re expected to be paid in adulation and glory, should any come our way. But if that’s the only carrot, we may end up very poor indeed.

Successful authors may have a different view on the writerly life than mine. It would make sense to connect with some of them, to seek out their advice and support. Edna O’Brien might be helpful in this regard. Given her extensive oeuvre, and the many book launches and events under her belt, she must be well equipped to deal with the pressures of author life. Philip Roth once called her the greatest living woman writing in English. As far as I know, he has yet to pass comment on my own abilities. Perhaps he’s still poring over the wording. He obviously doesn’t need any help in that regard, but I’d be happy to offer suggestions. For instance:

On the strength of his first book, Francis Plug may well be the greatest writer that ever lived. Which is why, when I die, I’m setting aside a portion of my will for his future development. I encourage all other ageing authors of standing to do the same.

Edna O’Brien is being interviewed by Professor John Mullan as part of a live Book Club event. There’ll be a book signing after, so it’s a good chance to ‘touch base’.

FP: I can really identify with your Country Girls characters at the moment.

Edna O’Brien: Oh yes?

FP: Yes. Especially when they go from the countryside to the big city. Because I was a gardener, working in gardens, and now I’m a glitzy published author.

Edna O’Brien: Is that right?

FP: Yes. My photo was in the Sunday Times. And I’ve been interviewed on the BBC. But I’m completely out of my depth. Truth be told, I feel like a lumping eejit.

Edna O’Brien: It can take a bit of getting used to.

FP: I’ll be kissing babies next. Do you have to do that?

Edna O’Brien: Kiss babies? Other people’s babies?

FP: Obviously I’d put my hand on their mouth and kiss that.

Edna O’Brien: Oh. What did you say your name was?

FP: Francis Plug.

Edna O’Brien: Francis Plug?

FP: Yes, have you heard of me?

Edna O’Brien: I haven’t, no.

FP: Darn. Oh, I like that bit in The Country Girls when Caithleen says, ‘I decided to drink, and drink, and drink, until I was very drunk.’

Edna O’Brien: Did you. What’s your book called?

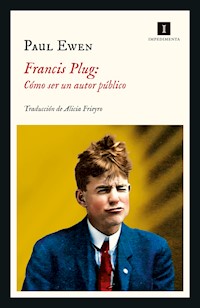

FP: How to Be a Public Author.

Edna O’Brien: I must look out for it.

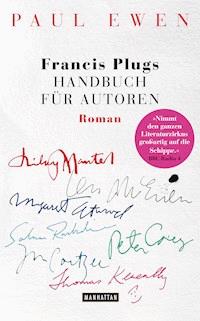

FP: Hilary Mantel has written a blurb for the cover.

Edna O’Brien: Has she? Really? What did she write?

FP: Well, she compared me to Goethe and Shelley…

Edna O’Brien: Gosh.

FP: And then she finished by saying I probably should be chained up.

Edna O’Brien: Chained up?

FP: Yes. I didn’t get that bit either.

While Edna O’Brien signs books, Professor John Mullan stands around awkwardly, looking a bit lost. He’s the Head of English Literature at the University of London, and it turns out, like Edna O’Brien, he’s written books too. Nabbing a copy of one from the desk, I use it as a foil for making conversation.

Professor John Mullan: Francis Plug? The author?

FP: Yes! You’ve read my book?

Professor John Mullan: No. But apparently I’m in it.

FP: Oh… right…

Professor John Mullan: I understand you make fun of my tight black top. And you accuse me of being a ‘microphone hog’.

FP: I think you’re reading too much into the text, Professor. It’s just a novel. And you can’t believe everything you read.

Professor John Mullan: How very profound.

FP: I didn’t know you’d written a book. Maybe I could interview you, on stage. That would be much better than me being interviewed by you. I wouldn’t have to answer all your befuddling literary questions.

Professor John Mullan: Befuddling?

FP: Yes, sir.

Professor John Mullan: But that’s rather the point of a book club, isn’t it? Asking befuddling literary questions?

FP: I guess. But if you’re an author it’s a total nightmare scenario.

Professor John Mullan: I think most authors actually relish the opportunity to delve deeper into their work.

FP: Doubt it. They just want to move on to the next thing, don’t they? All this critical analysis, it makes you go cross-eyed. Like this. [Cross-eyed expression.]

Professor John Mullan: Really. Well, if you’ll excuse me, I best circulate.

FP: Wait, I wondered if I might ask you something.

Professor John Mullan: Yes?

FP: The thing is, I’ve been put forward for a Writer in Residence position, at the University of Greenwich.

Professor John Mullan: You? A Writer in Residence? Good lord.

FP: Thanks. The thing is, I’m not particularly ‘academic’. I haven’t been blessed with a Cambridge education like yourself, so I don’t have loads of chums I can call on for a nod-nod, wink-wink, who’s-your-father, quick ascension up the ladder, as it were.

Professor John Mullan: I think you’ll find it doesn’t operate quite like that…

FP: Yes it does! [Laughing.] God! Everyone knows that!

Professor John Mullan: Really.

FP: The thing is, my gardening background doesn’t open many doors in the literary/academic worlds, so could you possibly put in a good word for me in Greenwich?

Professor John Mullan: Based on what, exactly?

FP: Um, well… this nice chat? And here, see… I have a copy of your book…

Professor John Mullan’s hardback book is rather expensive, and that’s one of the problems with drinking. You can make irrational, impulsive purchases. Not on this occasion fortunately, because theft is another problem brought on by drinking, especially when you’re hard up, due to the fact that you write books and aren’t paid to wang on about them as well.

Liberty department store is one of Britain’s most famous shops, first trading in 1875. It is contained within a Tudor revival building, and borders nearby Carnaby Street. This is all news to me too. I’ve never been near the place. As well as fancy, unusual items, Liberty also sells normal things, like plates. Except they cost a packet.

Salesperson: Do you like that one, sir?

FP: Well, it’s a pretty picture and all that. But seriously, you won’t even see it when it’s covered in gravy.

There are a number of coin pouches on offer. The leather ones are the most expensive, while the cheapest option is made of fabric and comes with a ‘fresh Art Nouveau-style finish’. It’s £65.

Finding the nearest pub, I spend a stupid sum on drinks instead.

It would be nice to have someone to share my writerly life with. But this of course is the author’s conundrum. You can’t become a big literary success if you’re out with your mates all the time, or having dinner with a prospective partner. You need to be sat down writing, by yourself. Fortunately, us authors are blessed with wonderful imaginations, so good friends and other halves can simply be conjured up. Sometimes, in my West Hampstead haunts, I’ll pretend I’m out with my nearest and dearest. If someone starts dragging a chair away, I might protest.

FP: Oi! You just tipped my mate on his arse!

Or, if they attempt to share my table:

FP: Hey! Get your big fat bum off my friend’s head!

In Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls, one of the nuns runs away with the gardener. Even with my gardening pedigree, I’ve had no advances from nuns. Having a garage for a home probably doesn’t help. After many drinks in the pub, following Liberty’s, I end up talking to two women, because of the many drinks.

FP: I’ve had a few drinks, yes. In fact, I can confidently say that I’m in no state to attend to a dying heifer, for instance.

Woman 1: What?

FP: I s’pose I better get myself back to the garage.

Woman 2: The garage?

FP: Yes, I live in a garage.

Woman 2: You live in a garage?

FP: Yes, a garage. Like the person who invented the Silicon Valley… that all started out of a garage, didn’t it? And those bands?

Woman 1: Maybe. But those garages probably had houses attached to them. They didn’t live in the garages.

FP: Did I tell you I was on the BBC?

Woman 2: Yes!

Woman 1: Jesus, he’s blotto, let’s run.