Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

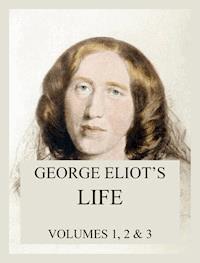

With the materials that the famous authoress has left behind, the editors have endeavored to form an autobiography (if the term may be permitted) of George Eliot. The life has been allowed to write itself in extracts from her letters and journals. Free from the obtrusion of any mind but her own, this method perfectly shows the development of her intellect and character. By arranging all the letters and journals so as to form one connected whole, keeping the order of their dates, and with the least possible interruption of comment, the result was a narrative of day-to-day life, with the play of light and shade which only letters, written in various moods, can give, and without which no portrait can be a good likeness. This volume contains all three original books and the complete lifespan of George Eliot from her first letter in 1838 to her death in the year 1880.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1421

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

George Eliot's Life

Volumes 1, 2 and 3

GEORGE ELIOT

George Eliot's Life, G. Eliot

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Deutschland

ISBN: 9783849650582

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

CONTENTS:

PREFACE.1

INTRODUCTORY SKETCH OF CHILDHOOD.3

CHAPTER I.15

CHAPTER II.31

CHAPTER III.53

CHAPTER IV.75

CHAPTER V.90

CHAPTER VI.119

CHAPTER VII.135

CHAPTER VIII.182

CHAPTER IX.209

CHAPTER X.241

CHAPTER XI.272

CHAPTER XII.299

CHAPTER XIII.333

CHAPTER XIV.345

CHAPTER XV.357

CHAPTER XVI.373

CHAPTER XVII.414

CHAPTER XVIII.444

CHAPTER XIX.470

PREFACE.

With the materials in my hands I have endeavored to form an autobiography (if the term may be permitted) of George Eliot. The life has been allowed to write itself in extracts from her letters and journals. Free from the obtrusion of any mind but her own, this method serves, I think, better than any other open to me, to show the development of her intellect and character.

In dealing with the correspondence I have been influenced by the desire to make known the woman, as well as the author, through the presentation of her daily life.

On the intellectual side there remains little to be learned by those who already know George Eliot's books. In the twenty volumes which she wrote and published in her lifetime will be found her best and ripest thoughts. The letters now published throw light on another side of her nature—not less important, but hitherto unknown to the public—the side of the affections.

The intimate life was the core of the root from which sprung the fairest flowers of her inspiration. Fame came to her late in life, and, when it presented itself, was so weighted with the sense of responsibility that it was in truth a rose with many thorns, for George Eliot had the temperament that shrinks from the position of a public character. The belief in the wide, and I may add in the beneficent, effect of her writing was no doubt the highest happiness, the reward of the artist which she greatly cherished: but the joys of the hearthside, the delight in the love of her friends, were the supreme pleasures in her life.

By arranging all the letters and journals so as to form one connected whole, keeping the order of their dates, and with the least possible interruption of comment, I have endeavored to combine a narrative of day-to-day life, with the play of light and shade which only letters, written in various moods, can give, and without which no portrait can be a good likeness. I do not know that the particular method in which I have treated the letters has ever been adopted before. Each letter has been pruned of everything that seemed to me irrelevant to my purpose—of everything that I thought my wife would have wished to be omitted. Every sentence that remains adds, in my judgment, something (however small it may be) to the means of forming a conclusion about her character. I ought perhaps to say a word of apology for what may appear to be undue detail of travelling experiences; but I hope that to many readers these will be interesting, as reflected through George Eliot's mind. The remarks on works of art are only meant to be records of impressions. She would have deprecated for herself the attitude of an art critic.

Excepting a slight introductory sketch of the girlhood, up to the time when letters became available, and a few words here and there to elucidate the correspondence, I have confined myself to the work of selection and arrangement.

I have refrained almost entirely from quoting remembered sayings by George Eliot, because it is difficult to be [vii] certain of complete accuracy, and everything depends upon accuracy. Recollections of conversation are seldom to be implicitly trusted in the absence of notes made at the time. The value of spoken words depends, too, so much upon the tone, and on the circumstances which gave rise to their utterance, that they often mislead as much as they enlighten, when, in the process of repetition, they have taken color from another mind. "All interpretations depend upon the interpreter," and I have judged it best to let George Eliot be her own interpreter, as far as possible.

I owe thanks to Mr. Isaac Evans, the brother of my wife, for much of the information in regard to her child-life; and the whole book is a long record of debts due to other friends for letters. It is not, therefore, necessary for me to recapitulate the list of names in this place. My thanks to all are heartfelt. But there is a very special acknowledgment due to Miss Sara Hennell, to Mrs. Bray, and to the late Mr. Charles Bray of Coventry, not only for the letters which they placed at my disposal, but also for much information given to me in the most friendly spirit. The very important part of the life from 1842 to 1854 could not possibly have been written without their contribution.

To Mr. Charles Lewes, also, I am indebted for some valuable letters and extracts from the journals of his father, besides the letters addressed to himself. He also obtained for me an important letter written by George Eliot to Mr. R. H. Hutton; and throughout the preparation of the book I have had the advantage of his sympathetic interest, and his concurrence in the publication of all the materials.

Special thanks are likewise due to Messrs. Wm. Blackwood & Sons for having placed at my disposal George Eliot's long correspondence with the firm. The letters (especially those addressed to her friend the late Mr. John Blackwood) throw a light, that could not otherwise have been obtained, on the most interesting part of her literary career.

To the legal representatives of the late Charles Dickens, of the late Lord Lytton, and of Mrs. Carlyle; to Mr. J. A. Froude, and to Mr. Archer Gurney, I owe thanks for leave to print letters written by them.

For all the defects that there may be in the plan of these volumes I alone am responsible. The lines were determined and the work was substantially put into shape before I submitted the manuscript to any one. While passing the winter in the south of France I had the good fortune at Cannes to find, in Lord Acton, not only an enthusiastic admirer of George Eliot, but also a friend always most kindly ready to assist me with valuable counsel and with cordial, generous sympathy. He was the first reader of the manuscript, and whatever accuracy may have been arrived at, particularly in the names of foreign books, foreign persons, and foreign places, is in great part due to his friendly, careful help. But of course he has no responsibility whatever for any of my sins of omission or commission.

By the kind permission of Sir Frederic Burton, I have been enabled to reproduce as a frontispiece M. Rajon's etching of the beautiful drawing, executed in 1864, now in the National Portrait Gallery, South Kensington.

The view of the old house at Rosehill is from a drawing by Mrs. Bray. It is connected with some of George Eliot's happiest experiences, and with the period of her most rapid intellectual development.

For permission to use the sketch of the drawing-room at the Priory I am indebted to the Messrs. Harpers, of New York.

In conclusion, it is in no conventional spirit, but from my heart, that I bespeak the indulgence of readers for my share of this work. Of its shortcomings no one can be so convinced as I am myself.

J. W. C.

Camden Hill, December, 1884.

INTRODUCTORY SKETCH OF CHILDHOOD.

"Nov. 22, 1819.—Mary Ann Evans was born at Arbury Farm, at five o'clock this morning."

This is an entry, in Mr. Robert Evans's handwriting, on the page of an old diary that now lies before me, and records, with characteristic precision, the birth of his youngest child, afterwards known to the world as George Eliot. Let us pause for a moment to pay its due homage to the precision, because it was in all probability to this most noteworthy quality of her father's nature that the future author was indebted for one of the principal elements of her own after-success—the enormous faculty for taking pains. The baby was born on St. Cecilia's day, and Mr. Evans, being a good churchman, takes her, on the 29th November, to be baptized in the church at Chilvers Coton—the parish in which Arbury Farm lies—a church destined to impress itself strongly on the child's imagination, and to be known by many people in many lands afterwards as Shepperton Church. The father was a remarkable man, and many of the leading traits in his character are to be found in Adam Bede and in Caleb Garth—although, of course, neither of these is a portrait. He was born in 1773, at Ellaston, in Staffordshire, son of a George Evans, who carried on the business of builder and carpenter there: the Evans family having come originally from Northop, in Flintshire. Robert was brought up to the business; but about 1799, or a little before, he held a farm of Mr. Francis Newdigate at Kirk Hallam, in Derbyshire, and became his agent. On Sir Roger Newdigate's death the Arbury estate came to Mr. Francis Newdigate for his life, and Mr. Evans accompanied him into Warwickshire, in 1806, in the capacity of agent. In 1801 he had married Harriott Poynton, by whom he had two children—Robert, born 1802, at Ellaston, and Frances Lucy, born 1805, at Kirk Hallam. His first wife died in 1809; and on 8th February, 1813, he married Christiana Pearson, by whom he had three children—Christiana, born 1814; Isaac, born 1816, and Mary Ann, born 1819. Shortly after the last child's birth, Robert, the son, became the agent, under his father, for the Kirk Hallam property, and lived there with his sister Frances, who afterwards married a Mr. Houghton. In March, 1820, when the baby girl was only four months old, the Evans family removed to Griff, a charming red-brick, ivy-covered house on the Arbury estate—"the warm little nest where her affections were fledged"—and there George Eliot spent the first twenty-one years of her life.

Let us remember what the England was upon which this observant child opened her eyes.

The date of her birth was removed from the beginning of the French Revolution by just the same period of time as separates a child, born this year, 1884, from the beginning of the Crimean War. To a man of forty-six to-day, the latter event seems but of yesterday. It took place at a very impressionable period of his life, and the remembrance of every detail is perfectly vivid. Mr. Evans was forty-six when his youngest child was born. He was a youth of sixteen when the Revolution began, and that mighty event, with all its consequences, had left an indelible impression on him, and the convictions and conclusions it had fostered in his mind permeated through to his children, and entered as an indestructible element into the susceptible soul of his youngest daughter. There are bits in the paper "Looking Backward," in "Theophrastus Such," which are true autobiography.

"In my earliest remembrance of my father his hair was already gray, for I was his youngest child, and it seemed to me that advanced age was appropriate to a father, as, indeed, in all respects I considered him a parent so much to my honor that the mention of my relationship to him was likely to secure me regard among those to whom I was otherwise a stranger—his stories from his life including so many names of distant persons that my imagination placed no limit to his acquaintanceship.... Nor can I be sorry, though myself given to meditative if not active innovation, that my father was a Tory who had not exactly a dislike to innovators and dissenters, but a slight opinion of them as persons of ill-founded self-confidence.... And I often smile at my consciousness that certain Conservative prepossessions have mingled themselves for me with the influences of our Midland scenery, from the tops of the elms down to the buttercups and the little wayside vetches. Naturally enough. That part of my father's prime to which he oftenest referred had fallen on the days when the great wave of political enthusiasm and belief in a speedy regeneration of all things had ebbed, and the supposed millennial initiative of France was turning into a Napoleonic empire.... To my father's mind the noisy teachers of revolutionary doctrine were, to speak mildly, a variable mixture of the fool and the scoundrel; the welfare of the nation lay in a strong government which could maintain order; and I was accustomed to hear him utter the word 'government' in a tone that charged it with awe, and made it part of my effective religion, in contrast with the word 'rebel,' which seemed to carry the stamp of evil in its syllables, and, lit by the fact that Satan was the first rebel, made an argument dispensing with more detailed inquiry."

This early association of ideas must always be borne in mind, as it is the key to a great deal in the mental attitude of the future thinker and writer. It is the foundation of the latent Conservative bias.

The year 1819 is memorable as a culminating period of bad times and political discontent in England. The nation was suffering acutely from the reaction after the excitement of the last Napoleonic war. George IV. did not come to the throne till January, 1820, so that George Eliot was born in the reign of George III. The trial of Queen Caroline was the topic of absorbing public interest. Waterloo was not yet an affair of five years old. Byron had four years, and Goethe had thirteen years, still to live. The last of Miss Austen's novels had been published only eighteen months, and the first of the Waverley series only six years before. Thackeray and Dickens were boys at school, and George Sand, as a girl of fifteen, was leaving her loved freedom on the banks of the Indre for the Convent des Anglaises at Paris. That "Greater Britain" (Canada and Australia), which to-day forms so large a reading public, was then scarcely more than a geographical expression, with less than half a million of inhabitants, all told, where at present there are eight millions; and in the United States, where more copies of George Eliot's books are now sold than in any other quarter of the world, the population then numbered less than ten millions where to-day it is fifty-five millions. Including Great Britain, these English-speaking races have increased from thirty millions in 1820 to one hundred millions in 1884; and with the corresponding increase in education we can form some conception how a popular English writer's fame has widened its circle.

There was a remoteness about a detached country-house, in the England of those days, difficult for us to conceive now, with our railways, penny-post, and telegraphs; nor is the Warwickshire country about Griff an exhilarating surrounding. There are neither hills nor vales, no rivers, lakes, or sea—nothing but a monotonous succession of green fields and hedgerows, with some fine trees. The only water to be seen is the "brown canal." The effect of such a landscape on an ordinary observer is not inspiring, but "effective magic is transcendent nature;" and with her transcendent nature George Eliot has transfigured these scenes, dear to Midland souls, into many an idyllic picture, known to those who know her books. In her childhood the great event of the day was the passing of the coach before the gate of Griff House, which lies at a bend of the high-road between Coventry and Nuneaton, and within a couple of miles of the mining village of Bedworth, "where the land began to be blackened with coal-pits, the rattle of hand-looms to be heard in hamlets and villages. Here were powerful men walking queerly, with knees bent outward from squatting in the mine, going home to throw themselves down in their blackened flannel and sleep through the daylight, then rise and spend much of their high wages at the alehouse with their fellows of the Benefit Club; here the pale, eager faces of hand-loom weavers, men and women, haggard from sitting up late at night to finish the week's work, hardly begun till the Wednesday. Everywhere the cottages and the small children were dirty, for the languid mothers gave their strength to the loom; pious Dissenting women, perhaps, who took life patiently, and thought that salvation depended chiefly on predestination, and not at all on cleanliness. The gables of Dissenting chapels now made a visible sign of religion, and of a meeting-place to counterbalance the alehouse, even in the hamlets.... Here was a population not convinced that old England was as good as possible; here were multitudinous men and women aware that their religion was not exactly the religion of their rulers, who might therefore be better than they were, and who, if better, might alter many things which now made the world perhaps more painful than it need be, and certainly more sinful. Yet there were the gray steeples too, and the churchyards, with their grassy mounds and venerable headstones, sleeping in the sunlight; there were broad fields and homesteads, and fine old woods covering a rising ground, or stretching far by the roadside, allowing only peeps at the park and mansion which they shut in from the working-day world. In these midland districts the traveller passed rapidly from one phase of English life to another; after looking down on a village dingy with coal-dust, noisy with the shaking of looms, he might skirt a parish all of fields, high hedges, and deep-rutted lanes; after the coach had rattled over the pavement of a manufacturing town, the scene of riots and trades-union meetings, it would take him in another ten minutes into a rural region, where the neighborhood of the town was only felt in the advantages of a near market for corn, cheese, and hay, and where men with a considerable banking account were accustomed to say that 'they never meddled with politics themselves.'"

We can imagine the excitement of a little four-year-old girl and her seven-year-old brother waiting, on bright frosty mornings, to hear the far-off ringing beat of the horses' feet upon the hard ground, and then to see the gallant appearance of the four grays, with coachman and guard in scarlet, outside passengers muffled up in furs, and baskets of game and other packages hanging behind the boot, as his majesty's mail swung cheerily round on its way from Birmingham to Stamford. Two coaches passed the door daily—one from Birmingham at 10 o'clock in the morning, the other from Stamford at 3 o'clock in the afternoon. These were the chief connecting links between the household at Griff and the outside world. Otherwise life went on with that monotonous regularity which distinguishes the country from the town. And it is to these circumstances of her early life that a great part of the quality of George Eliot's writing is due, and that she holds the place she has attained in English literature. Her roots were down in the pre-railroad, pre-telegraphic period—the days of fine old leisure—but the fruit was formed during an era of extraordinary activity in scientific and mechanical discovery. Her genius was the outcome of these conditions. It would not have existed in the same form deprived of either influence. Her father was busy both with his own farm-work and increasing agency business. He was already remarked in Warwickshire for his knowledge and judgment in all matters relating to land, and for his general trustworthiness and high character, so that he was constantly selected as arbitrator and valuer. He had a wonderful eye, especially for valuing woods, and could calculate with almost absolute precision the quantity of available timber in a standing tree. In addition to his merits as a man of business, he had the good fortune to possess the warm friendship and consistent support of Colonel Newdigate of Astley Castle, son of Mr. Francis Newdigate of Arbury, and it was mainly through the colonel's introduction and influence that Mr. Evans became agent also to Lord Aylesford, Lord Lifford, Mr. Bromley Davenport, and several others.

His position cannot be better summed up than in the words of his daughter, writing to Mr. Bray on 30th September, 1859, in regard to some one who had written of her, after the appearance of "Adam Bede," as a "self-educated farmer's daughter."

"My father did not raise himself from being an artisan to be a farmer; he raised himself from being an artisan to be a man whose extensive knowledge in very varied practical departments made his services valued through several counties. He had large knowledge of building, of mines, of plantations, of various branches of valuation and measurement—of all that is essential to the management of large estates. He was held by those competent to judge as unique among land-agents for his manifold knowledge and experience, which enabled him to save the special fees usually paid by landowners for special opinions on the different questions incident to the proprietorship of land. So far as I am personally concerned I should not write a stroke to prevent any one, in the zeal of antithetic eloquence, from calling me a tinker's daughter; but if my father is to be mentioned at all—if he is to be identified with an imaginary character—my piety towards his memory calls on me to point out to those who are supposed to speak with information what he really achieved in life."

Mr. Evans was also, like Adam Bede, noteworthy for his extraordinary physical strength and determination of character. There is a story told of him, that one day when he was travelling on the top of a coach, down in Kent, a decent woman sitting next him complained that a great hulking sailor on her other side was making himself offensive. Mr. Evans changed places with the woman, and, taking the sailor by the collar, forced him down under the seat, and held him there with an iron hand for the remainder of the stage: and at Griff it is still remembered that the master, happening to pass one day while a couple of laborers were waiting for a third to help to move the high, heavy ladder used for thatching ricks, braced himself up to a great effort, and carried the ladder alone and unaided from one rick to the other, to the wide-eyed wonder and admiration of his men. With all this strength, however, both of body and of character, he seems to have combined a certain self-distrust, owing, perhaps, to his early imperfect education, which resulted in a general submissiveness in his domestic relations, more or less portrayed in the character of Mr. Garth.

His second wife was a woman with an unusual amount of natural force; a shrewd, practical person, with a considerable dash of the Mrs. Poyser vein in her. Hers was an affectionate, warm-hearted nature, and her children, on whom she cast "the benediction of her gaze," were thoroughly attached to her. She came of a race of yeomen, and her social position was, therefore, rather better than her husband's at the time of their marriage. Her family are, no doubt, prototypes of the Dodsons in the "Mill on the Floss." There were three other sisters married, and all living in the neighborhood of Griff—Mrs. Everard, Mrs. Johnson, and Mrs. Garner—and probably Mr. Evans heard a good deal about "the traditions in the Pearson family." Mrs. Evans was a very active, hard-working woman, but shortly after her last child's birth she became ailing in health, and consequently her eldest girl, Christiana, was sent to school, at a very early age, to Miss Lathom's, at Attleboro, a village a mile or two from Griff, while the two younger children spent some part of their time every day at the cottage of a Mrs. Moore, who kept a dame's school close to Griff gates. The little girl very early became possessed with the idea that she was going to be a personage in the world; and Mr. Charles Lewes has told me an anecdote which George Eliot related of herself as characteristic of this period of her childhood. When she was only four years old she recollected playing on the piano, of which she did not know one note, in order to impress the servant with a proper notion of her acquirements and generally distinguished position. This was the time when the love for her brother grew into the child's affections. She used always to be at his heels, insisting on doing everything he did. She was not, in these baby-days, in the least precocious in learning. In fact, her half-sister, Mrs. Houghton, who was some fourteen years her senior, told me that the child learned to read with some difficulty; but Mr. Isaac Evans says that this was not from any slowness in apprehension, but because she liked playing so much better. Mere sharpness, however, was not a characteristic of her mind. Hers was a large, slow-growing nature; and I think it is, at any rate, certain that there was nothing of the infant phenomenon about her. In her moral development she showed, from the earliest years, the trait that was most marked in her all through life, namely, the absolute need of some one person who should be all in all to her, and to whom she should be all in all. Very jealous in her affections, and easily moved to smiles or tears, she was of a nature capable of the keenest enjoyment and the keenest suffering, knowing "all the wealth and all the woe" of a pre-eminently exclusive disposition. She was affectionate, proud, and sensitive in the highest degree.

The sort of happiness that belongs to this budding-time of life, from the age of three to five, is apt to impress itself very strongly on the memory; and it is this period which is referred to in the Brother and Sister Sonnet, "But were another childhood's world my share, I would be born a little sister there." When her brother was eight years old he was sent to school at Coventry, and, her mother continuing in very delicate health, the little Mary Ann, now five years of age, went to join her sister at Miss Lathom's school, at Attleboro, where they continued as boarders for three or four years, coming, occasionally, home to Griff on Saturdays. During one of our walks at Witley, in 1880, my wife mentioned to me that what chiefly remained in her recollection about this very early school-life was the difficulty of getting near enough the fire in winter to become thoroughly warmed, owing to the circle of girls forming round too narrow a fireplace. This suffering from cold was the beginning of a low general state of health; also at this time she began to be subject to fears at night—"the susceptibility to terror"—which she has described as haunting Gwendolen Harleth in her childhood. The other girls in the school, who were all, naturally, very much older, made a great pet of the child, and used to call her "little mamma," and she was not unhappy except at nights; but she told me that this liability to have "all her soul become a quivering fear," which remained with her afterwards, had been one of the supremely important influences dominating at times her future life. Mr. Isaac Evans's chief recollection of this period is the delight of the little sister at his home-coming for holidays, and her anxiety to know all that he had been doing and learning. The eldest child, who went by the name of Chrissey, was the chief favorite of the aunts, as she was always neat and tidy, and used to spend a great deal of her time with them, while the other two were inseparable playfellows at home. The boy was his mother's pet and the girl her father's. They had everything to make children happy at Griff—a delightful old-fashioned garden, a pond and the canal to fish in, and the farm-offices close to the house, "the long cow-shed, where generations of the milky mothers have stood patiently, the broad-shouldered barns, where the old-fashioned flail once made resonant music," and where butter-making and cheese-making were carried on with great vigor by Mrs. Evans.

Any one, about this time, who happened to look through the window on the left-hand side of the door of Griff House would have seen a pretty picture in the dining-room on Saturday evenings after tea. The powerful, middle-aged man with the strongly marked features sits in his deep, leather-covered arm-chair, at the right-hand corner of the ruddy fireplace, with the head of "the little wench" between his knees. The child turns over the book with pictures that she wishes her father to explain to her—or that perhaps she prefers explaining to him. Her rebellious hair is all over her eyes, much vexing the pale, energetic mother who sits on the opposite side of the fire, cumbered with much service, letting no instant of time escape the inevitable click of the knitting-needles, accompanied by epigrammatic speech. The elder girl, prim and tidy, with her work before her, is by her mother's side; and the brother, between the two groups, keeps assuring himself by perpetual search that none of his favorite means of amusement are escaping from his pockets. The father is already very proud of the astonishing and growing intelligence of his little girl. From a very early age he has been in the habit of taking her with him in his drives about the neighborhood, "standing between her father's knees as he drove leisurely," so that she has drunk in knowledge of the country and of country folk at all her pores. An old-fashioned child, already living in a world of her own imagination, impressible to her finger-tips, and willing to give her views on any subject.

The first book that George Eliot read, so far as I have been able to ascertain, was a little volume published in 1822, entitled "The Linnet's Life," which she gave to me in the last year of her life, at Witley. It bears the following inscription, written some time before she gave it to me:

"This little book is the first present I ever remember having received from my father. Let any one who thinks of me with some tenderness after I am dead take care of this book for my sake. It made me very happy when I held it in my little hands, and read it over and over again; and thought the pictures beautiful, especially the one where the linnet is feeding her young."

It must, I think, have been very shortly after she received this present that an old friend of the family, who was in the habit of coming as a visitor to Griff from time to time, used occasionally to bring a book in his hand for the little girl. I very well remember her expressing to me deep gratitude for this early ministration to her childish delights; and Mr. Burne Jones has been kind enough to tell me of a conversation with George Eliot about children's books, when she also referred to this old gentleman's kindness. They were agreeing in disparagement of some of the books that the rising generation take their pleasure in, and she recalled the dearth of child-literature in her own home, and her passionate delight and total absorption in Æsop's Fables (given to her by the aforesaid old gentleman), the possession of which had opened new worlds to her imagination. Mr. Burne Jones particularly remembers how she laughed till the tears ran down her face in recalling her infantine enjoyment of the humor in the fable of Mercury and the Statue-seller. Having so few books at this time, she read them again and again, until she knew them by heart. One of them was a Joe Miller jest-book, with the stories from which she used greatly to astonish the family circle. But the beginning of her serious reading-days did not come till later. Meantime her talent for observation gained a glorious new field for employment in her first journey from home, which took place in 1826. Her father and mother took her with them on a little trip into Derbyshire and Staffordshire, where she saw Mr. Evans's relations, and they came back through Lichfield, sleeping at the Swan. They were away only a week, from the 18th to the 24th of May; but "what time is little" to an imaginative, observant child of seven on her first journey? About this time a deeply felt crisis occurred in her life, as her brother had a pony given to him, to which he became passionately attached. He developed an absorbing interest in riding, and cared less and less to play with his sister. The next important event happened in her eighth or ninth year, when she was sent to Miss Wallington's school at Nuneaton with her sister. This was a much larger school than Miss Lathom's, there being some thirty girls, boarders. The principal governess was Miss Lewis, who became then, and remained for many years after, Mary Ann Evans's most intimate friend and principal correspondent, and I am indebted to the letters addressed to her from 1836 to 1842 for most of the information concerning that period. Books now became a passion with the child; she read everything she could lay hands on, greatly troubling the soul of her mother by the consumption of candles as well as of eyesight in her bedroom. From a subsequent letter it will be seen that she was "early supplied with works of fiction by those who kindly sought to gratify her appetite for reading."

It must have been about this time that the episode occurred in relation to "Waverley" which is mentioned by Miss Simcox in her article in the June, 1881, number of the Nineteenth Century Review. It was quite new to me, and, as it is very interesting, I give it in Miss Simcox's own words: "Somewhere about 1827 a friendly neighbor lent 'Waverley' to an elder sister of little Mary Ann Evans. It was returned before the child had read to the end, and, in her distress at the loss of the fascinating volume, she began to write out the story as far as she had read it for herself, beginning naturally where the story begins with Waverley's adventures at Tully Veolan, and continuing until the surprised elders were moved to get her the book again." Miss Simcox has pointed out the reference to this in the motto of the 57th chapter of "Middlemarch:"

"They numbered scarce eight summers when a nameRose on their souls and stirred such motions thereAs thrill the buds and shape their hidden frameAt penetration of the quickening air:His name who told of loyal Evan Dhu,Of quaint Bradwardine, and Vich Ian Vor,Making the little world their childhood knewLarge with a land of mountain, lake, and scaur,And larger yet with wonder, love, beliefTowards Walter Scott, who, living far away,Sent them this wealth of joy and noble grief.The book and they must part, but, day by day,In lines that thwart like portly spiders ran,They wrote the tale, from Tully Veolan."

Miss Simcox also mentions that "Elia divided her childish allegiance with Scott, and she remembered feasting with singular pleasure upon an extract in some stray almanac from the essay in commemoration of 'Captain Jackson and his slender ration of Single Gloucester.' This is an extreme example of the general rule that a wise child's taste in literature is sounder than adults generally venture to believe."

We know, too, from the "Mill on the Floss" that the "History of the Devil," by Daniel Defoe, was a favorite. The book is still religiously preserved at Griff, with its pictures just as Maggie looked at them. "The Pilgrim's Progress," also, and "Rasselas" had a large share of her affections.

At Miss Wallington's the growing girl soon distinguished herself by an easy mastery of the usual school-learning of her years, and there, too, the religious side of her nature was developed to a remarkable degree. Miss Lewis was an ardent Evangelical Churchwoman, and exerted a strong influence on her young pupil, whom she found very sympathetically inclined. But Mary Ann Evans did not associate freely with her schoolfellows, and her friendship with Miss Lewis was the only intimacy she indulged in.

On coming home for their holidays the sister and brother began, about this time, the habit of acting charades together before the Griff household and the aunts, who were greatly impressed with the cleverness of the performance; and the girl was now recognized in the family circle as no ordinary child.

Another epoch presently succeeded, on her removal to Miss Franklin's school at Coventry, in her thirteenth year. She was probably then very much what she has described her own Maggie at the age of thirteen:

"A creature full of eager, passionate longings for all that was beautiful and glad; thirsty for all knowledge; with an ear straining after dreamy music that died away and would not come near to her; with a blind, unconscious yearning for something that would link together the wonderful impressions of this mysterious life, and give her soul a sense of home in it. No wonder, when there is this contrast between the outward and the inward, that painful collisions come of it."

In Our Times of June, 1881, there is a paper by a lady whose mother was at school with Mary Ann Evans, which gives some interesting particulars of the Miss Franklins.

"They were daughters of a Baptist minister who had preached for many years in Coventry, and who inhabited, during his pastorate, a house in the chapel-yard almost exactly resembling that of Rufus Lyon in 'Felix Holt.' For this venerable gentleman Miss Evans, as a schoolgirl, had a great admiration, and I, who can remember him well, can trace in Rufus Lyon himself many slight resemblances, such as the 'little legs,' and the habit of walking up and down when composing. Miss Rebecca Franklin was a lady of considerable intellectual power, and remarkable for her elegance in writing and conversation, as well as for her beautiful calligraphy. In her classes for English Composition Mary Ann Evans was, from her first entering the school, far in advance of the rest; and while the themes of the other children were read, criticised, and corrected in class, hers were reserved for the private perusal and enjoyment of the teacher, who rarely found anything to correct. Her enthusiasm for music was already very strongly marked, and her music-master, a much-tried man, suffering from the irritability incident to his profession, reckoned on his hour with her as a refreshment to his wearied nerves, and soon had to confess that he had no more to teach her. In connection with this proficiency in music, my mother recalls her sensitiveness at that time as being painfully extreme. When there were visitors, Miss Evans, as the best performer in the school, was sometimes summoned to the parlor to play for their amusement, and though suffering agonies from shyness and reluctance, she obeyed with all readiness, but, on being released, my mother has often known her to rush to her room and throw herself on the floor in an agony of tears. Her schoolfellows loved her as much as they could venture to love one whom they felt to be so immeasurably superior to themselves, and she had playful nicknames for most of them. My mother, who was delicate, and to whom she was very kind, was dubbed by her 'Miss Equanimity.' A source of great interest to the girls, and of envy to those who lived farther from home, was the weekly cart which brought Miss Evans new-laid eggs and other delightful produce of her father's farm."

In talking about these early days, my wife impressed on my mind the debt she felt that she owed to the Miss Franklins for their excellent instruction, and she had also the very highest respect for their moral qualities. With her chameleon-like nature she soon adopted their religious views with intense eagerness and conviction, although she never formally joined the Baptists or any other communion than the Church of England. She at once, however, took a foremost place in the school, and became a leader of prayer-meetings among the girls. In addition to a sound English education the Miss Franklins managed to procure for their pupils excellent masters for French, German, and music; so that, looking to the lights of those times, the means of obtaining knowledge were very much above the average for girls. Her teachers, on their side, were very proud of their exceptionally gifted scholar; and years afterwards, when Miss Evans came with her father to live in Coventry, they introduced her to one of their friends, not only as a marvel of mental power, but also as a person "sure to get something up very soon in the way of clothing-club or other charitable undertaking."

This year, 1832, was not only memorable for the change to a new and superior school, but it was also much more memorable to George Eliot for the riot which she saw at Nuneaton, on the occasion of the election for North Warwickshire, after the passing of the great Reform Bill, and which subsequently furnished her with the incidents for the riot in "Felix Holt." It was an event to lay hold on the imagination of an impressionable girl of thirteen, and it is thus described in the local newspaper of 29th December, 1832:

"On Friday, the 21st December, at Nuneaton, from the commencement of the poll till nearly half-past two, the Hemingites occupied the poll; the numerous plumpers for Sir Eardley Wilmot and the adherents of Mr. Dugdale being constantly interrupted in their endeavors to go to the hustings to give an honest and conscientious vote. The magistrates were consequently applied to, and from the representations they received from all parties, they were at length induced to call in aid a military force. A detachment of the Scots Greys accordingly arrived; but it appearing that that gallant body was not sufficiently strong to put down the turbulent spirit of the mob, a reinforcement was considered by the constituted authorities as absolutely necessary. The tumult increasing, as the detachment of the Scots Greys were called in, the Riot Act was read from the windows of the Newdigate Arms; and we regret to add that both W. P. Inge, Esq., and Colonel Newdigate, in the discharge of their magisterial duties, received personal injuries.

"On Saturday the mob presented an appalling appearance, and but for the forbearance of the soldiery numerous lives would have fallen a sacrifice. Several of the officers of the Scots Greys were materially hurt in their attempt to quell the riotous proceedings of the mob. During the day the sub-sheriffs at the different booths received several letters from the friends of Mr. Dugdale, stating that they were outside of the town, and anxious to vote for that gentleman, but were deterred from entering it from fear of personal violence. Two or three unlucky individuals, drawn from the files of the military on their approach to the poll, were cruelly beaten, and stripped literally naked. We regret to add that one life has been sacrificed during the contest, and that several misguided individuals have been seriously injured."

The term ending Christmas, 1835, was the last spent at Miss Franklin's. In the first letter of George Eliot's that I have been able to discover, dated 6th January, 1836, and addressed to Miss Lewis, who was at that time governess in the family of the Rev. L. Harper, Burton Latimer, Northamptonshire, she speaks of her mother having suffered a great increase of pain, and adds—

"We dare not hope that there will be a permanent improvement. Our anxieties on my mother's account, though so great, have been since Thursday almost lost sight of in the more sudden, and consequently more severe, trial which we have been called on to endure in the alarming illness of my dear father. For four days we had no cessation of our anxiety; but I am thankful to say that he is now considered out of danger, though very much reduced by frequent bleeding and very powerful medicines."

In the summer of this year—1836—the mother died, after a long, painful illness, in which she was nursed with great devotion by her daughters. It was their first acquaintance with death; and to a highly wrought, sensitive girl of sixteen such a loss seems an unendurable calamity. "To the old, sorrow is sorrow; to the young, it is despair." Many references will be found in the subsequent correspondence to what she suffered at this time, all summed up in the old popular phrase, "We can have but one mother." In the following spring Christiana was married to Mr. Edward Clarke, a surgeon practising at Meriden, in Warwickshire. One of Mr. Isaac Evans's most vivid recollections is that on the day of the marriage, after the bride's departure, he and his younger sister had "a good cry" together over the break-up of the old home-life, which of course could never be the same with the mother and the elder sister wanting.

Twenty-three years later we shall find George Eliot writing, on the death of this sister, that she "had a very special feeling for her—stronger than any third person would think likely." The relation between the sisters was somewhat like that described as existing between Dorothea and Celia in "Middlemarch"—no intellectual affinity, but a strong family affection. In fact, my wife told me, that although Celia was not in any sense a portrait of her sister, she "had Chrissey continually in mind" in delineating Celia's character. But we must be careful not to found too much on such suggestions of character in George Eliot's books; and this must particularly be borne in mind in the "Mill on the Floss." No doubt the early part of Maggie's portraiture is the best autobiographical representation we can have of George Eliot's own feelings in her childhood, and many of the incidents in the book are based on real experiences of family life, but so mixed with fictitious elements and situations that it would be absolutely misleading to trust to it as a true history. For instance, all that happened in real life between the brother and sister was, I believe, that as they grew up their characters, pursuits, and tastes diverged more and more widely. He took to his father's business, at which he worked steadily, and which absorbed most of his time and attention. He was also devoted to hunting, liked the ordinary pleasures of a young man in his circumstances, and was quite satisfied with the circle of acquaintance in which he moved. After leaving school at Coventry he went to a private tutor's at Birmingham, where he imbibed strong High-Church views. His sister had come back from the Miss Franklins' with ultra-Evangelical tendencies, and their differences of opinion used to lead to a good deal of animated argument. Miss Evans, as she now was, could not rest satisfied with a mere profession of faith without trying to shape her own life—and, it may be added, the lives around her—in accordance with her convictions. The pursuit of pleasure was a snare; dress was vanity; society was a danger.

"From what you know of her, you will not be surprised that she threw some exaggeration and wilfulness, some pride and impetuosity, even into her self-renunciation: her own life was still a drama for her, in which she demanded of herself that her part should be played with intensity. And so it came to pass that she often lost the spirit of humility by being excessive in the outward act; she often strove after too high a flight, and came down with her poor little half-fledged wings dabbled in the mud.... That is the path we all like when we set out on our abandonment of egoism—the path of martyrdom and endurance, where the palm-branches grow, rather than the steep highway of tolerance, just allowance, and self-blame, where there are no leafy honors to be gathered and worn."

After Christiana's marriage the entire charge of the Griff establishment devolved on Mary Ann, who became a most exemplary housewife, learned thoroughly everything that had to be done, and, with her innate desire for perfection, was never satisfied unless her department was administered in the very best manner that circumstances permitted. She spent a great deal of time in visiting the poor, organizing clothing-clubs, and other works of active charity. But over and above this, as will be seen from the following letters, she was always prosecuting an active intellectual life of her own. Mr. Brezzi, a well-known master of modern languages at Coventry, used to come over to Griff regularly to give her lessons in Italian and German. Mr. M'Ewen, also from Coventry, continued her lessons in music, and she got through a large amount of miscellaneous reading by herself. In the evening she was always in the habit of playing to her father, who was very fond of music. But it requires no great effort of imagination to conceive that this life, though full of interests of its own, and the source from whence the future novelist drew the most powerful and the most touching of her creations, was, as a matter of fact, very monotonous, very difficult, very discouraging. It could scarcely be otherwise to a young girl with a full, passionate nature and hungry intellect, shut up in a farmhouse in the remote country. For there was no sympathetic human soul near with whom to exchange ideas on the intellectual and spiritual problems that were beginning to agitate her mind. "You may try, but you can never imagine what it is to have a man's force of genius in you, and yet to suffer the slavery of being a girl." This is a point of view that must be distinctly recognized by any one attempting to follow the development of George Eliot's character, and it will always be corrected by the other point of view which she has made so prominent in all her own writing—the soothing, strengthening, sacred influences of the home life, the home loves, the home duties. Circumstances in later life separated her from her kindred, but among her last letters it will be seen that she wrote to her brother in May, 1880, that "our long silence has never broken the affection for you that began when we were little ones" —and she expresses her satisfaction in the growing prosperity of himself and all his family. It was a real gratification to her to hear from some Coventry friends that her nephew, the Rev. Frederic Evans, the present rector of Bedworth, was well spoken of as a preacher in the old familiar places, and in our last summer at Witley we often spoke of a visit to Warwickshire, that she might renew the sweet memories of her child-days. No doubt, the very monotony of her life at Griff, and the narrow field it presented for observation of society, added immeasurably to the intensity of a naturally keen mental vision, concentrating into a focus what might perhaps have become dissipated in more liberal surroundings. And though the field of observation was narrow in one sense, it included very various grades of society. Such fine places as Arbury, and Packington, the seat of Lord Aylesford, where she was being constantly driven by her father, affected the imagination and accentuated the social differences—differences which had a profound significance for such a sensitive and such an intellectually commanding character, and which left their mark on it.

"No one who has not a strong natural prompting and susceptibility towards such things [the signs and luxuries of ladyhood] and has, at the same time, suffered from the presence of opposite conditions, can understand how powerfully those minor accidents of rank which please the fastidious sense can preoccupy the imagination."

The tone of her mind will be seen from the letters written during the following years, and I remember once, after we were married, when I was urging her to write her autobiography, she said, half sighing, half smiling, "The only thing I should care much to dwell on would be the absolute despair I suffered from of ever being able to achieve anything. No one could ever have felt greater despair, and a knowledge of this might be a help to some other struggler"—adding, with a smile, "but, on the other hand, it might only lead to an increase of bad writing."

CHAPTER I.

In the foregoing introductory sketch I have endeavored to present the influences to which George Eliot was subjected in her youth, and the environment in which she grew up; I am now able to begin the fulfilment of the promise on the titlepage, that the life will be related in her own letters; or, rather, in extracts from her own letters, for no single letter is printed entire from the beginning to the end. I have not succeeded in obtaining any between 6th January, 1836, and 18th August, 1838; but from the latter date the correspondence becomes regular, and I have arranged it as a continuous narrative, with the names of the persons to whom the letters are addressed in the margin. The slight thread of narrative or explanation which I have written to elucidate the letters, where necessary, will hereafter occupy an inside margin, so that the reader will see at a glance what is narrative and what is correspondence, and will be troubled as little as possible with marks of quotation or changes of type.

The following opening letter of the series to Miss Lewis describes a first visit to London with her brother:

Letter to Miss Lewis, 18th Aug. 1838.

Let me tell you, though, that I was not at all delighted with the stir of the great Babel, and the less so, probably, owing to the circumstances attending my visit thither. Isaac and I went alone (that seems rather Irish), and stayed only a week, every day of which we worked hard at seeing sights. I think Greenwich Hospital interested me more than anything else.

Mr. Isaac Evans himself tells me that what he remembers chiefly impressed her was the first hearing the great bell of St. Paul's. It affected her deeply. At that time she was so much under the influence of religious and ascetic ideas that she would not go to any of the theatres with her brother, but spent all her evenings alone, reading. A characteristic reminiscence is that the chief thing she wanted to buy was Josephus's "History of the Jews;" and at the same bookshop her brother got her this he bought for himself a pair of hunting sketches. In the same letter, alluding to the marriage of one of her friends, she says:

Letter to Miss Lewis, 18th Aug. 1838.

For my part, when I hear of the marrying and giving in marriage that is constantly being transacted, I can only sigh for those who are multiplying earthly ties which, though powerful enough to detach their hearts and thoughts from heaven, are so brittle as to be liable to be snapped asunder at every breeze. You will think that I need nothing but a tub for my habitation to make me a perfect female Diogenes; and I plead guilty to occasional misanthropical thoughts, but not to the indulgence of them. Still, I must believe that those are happiest who are not fermenting themselves by engaging in projects for earthly bliss, who are considering this life merely a pilgrimage, a scene calling for diligence and watchfulness, not for repose and amusement. I do not deny that there may be many who can partake with a high degree of zest of all the lawful enjoyments the world can offer, and yet live in near communion with their God—who can warmly love the creature, and yet be careful that the Creator maintains his supremacy in their hearts; but I confess that, in my short experience and narrow sphere of action, I have never been able to attain to this. I find, as Dr. Johnson said respecting his wine, total abstinence much easier than moderation. I do not wonder you are pleased with Pascal; his thoughts may be returned to the palate again and again with increasing rather than diminished relish. I have highly enjoyed Hannah More's letters; the contemplation of so blessed a character as hers is very salutary. "That ye be not slothful, but followers of them who, through faith and patience, inherit the promises," is a valuable admonition. I was once told that there was nothing out of myself to prevent my becoming as eminently holy as St. Paul; and though I think that is too sweeping an assertion, yet it is very certain we are generally too low in our aims, more anxious for safety than sanctity, for place than purity, forgetting that each involves the other, and that, as Doddridge tells us, to rest satisfied with any attainments in religion is a fearful proof that we are ignorant of the very first principles of it. O that we could live only for eternity! that we could realize its nearness! I know you do not love quotations, so I will not give you one; but if you do not distinctly remember it, do turn to the passage in Young's "Infidel Reclaimed," beginning, "O vain, vain, vain all else eternity," and do love the lines for my sake.

I really feel for you, sacrificing, as you are, your own tastes and comforts for the pleasure of others, and that in a manner the most trying to rebellious flesh and blood; for I verily believe that in most cases it requires more of a martyr's spirit to endure, with patience and cheerfulness, daily crossings and interruptions of our petty desires and pursuits, and to rejoice in them if they can be made to conduce to God's glory and our own sanctification, than even to lay down our lives for the truth.

Letter to Miss Lewis, 6th Nov. 1838.

I can hardly repress a sort of indignation towards second causes. That your time and energies should be expended in ministering to the petty interests of those far beneath you in all that is really elevating is about as bienséant as that I should set fire to a goodly volume to light a match by! I have had a very unsettled life lately—Michaelmas, with its onerous duties and anxieties, much company (for us) and little reading, so that I am ill prepared for corresponding with profit or pleasure. I am generally in the same predicament with books as a glutton with his feast, hurrying through one course that I may be in time for the next, and so not relishing or digesting either; not a very elegant illustration, but the best my organs of ideality and comparison will furnish just now.

I have just begun the "Life of Wilberforce," and I am expecting a rich treat from it. There is a similarity, if I may compare myself with such a man, between his temptations, or rather besetments, and my own, that makes his experience very interesting to me. O that I might be made as useful in my lowly and obscure station as he was in the exalted one assigned to him! I feel myself to be a mere cumberer of the ground. May the Lord give me such an insight into what is truly good that I may not rest contented with making Christianity a mere addendum to my pursuits, or with tacking it as a fringe to my garments! May I seek to be sanctified wholly! My nineteenth birthday will soon be here (the 22d)—an awakening signal. My mind has been much clogged lately by languor of body, to which I am prone to give way, and for the removal of which I shall feel thankful.

We have had an oratorio at Coventry lately, Braham, Phillips, Mrs. Knyvett, and Mrs. Shaw—the last, I think, I shall attend. I am not fitted to decide on the question of the propriety or lawfulness of such exhibitions of talent and so forth, because I have no soul for music. "Happy is he that condemneth not himself in that thing which he alloweth." I am a tasteless person, but it would not cost me any regrets if the only music heard in our land were that of strict worship, nor can I think a pleasure that involves the devotion of all the time and powers of an immortal being to the acquirement of an expertness in so useless (at least in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred) an accomplishment, can be quite pure or elevating in its tendency.

The above remarks on oratorio are the more surprising because, two years later, when Miss Evans went to the Birmingham festival, in September, 1840, previous to her brother's marriage, she was affected to an extraordinary degree, so much so that Mrs. Isaac Evans—then Miss Rawlins—told me that the attention of people sitting near was attracted by her hysterical sobbing. And in all her later life music was one of the chiefest delights to her, and especially oratorio.

"Not that her enjoyment of music was of the kind that indicates a great specific talent; it was rather that her sensibility to the supreme excitement of music was only one form of that passionate sensibility which belonged to her whole nature, and made her faults and virtues all merge in each other—made her affections sometimes an impatient demand, but also prevented her vanity from taking the form of mere feminine coquetry and device, and gave it the poetry of ambition."

The next two letters, dated from Griff—February 6th and March 5th, 1839—are addressed to Mrs. Samuel Evans, a Methodist preacher, the wife of a younger brother of Mr. Robert Evans. They are the more interesting from the fact, which will appear later, that an anecdote related by this aunt during her visit to Griff in 1839 was the germ of "Adam Bede." To what extent this Elizabeth Evans resembled the ideal character of Dinah Morris will also be seen in its place in the history of "Adam Bede."

Letter to Mrs. Samuel Evans, 6th Feb. 1839.