Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dreamspinner Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

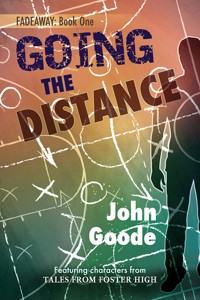

Fadeaway: Book One From the Tales from Foster High Universe Looking like the perfect all-American boy—tall, handsome, and athletic—makes it easy for Danny Monroe to blend in with the in-crowd of a new high school. It's a trick he picked up moving with his father from one Marine base to the next. When you aren't going to be around long, it's better to give people what they want. And what they want are his quick hands and fast feet on the basketball court. On court, he can be himself and ignore certain strange developing urges. Everyone knows you can't like boys and be a jock, but for Danny his growing attraction is becoming overwhelming. At the thought of losing the only thing that matters, Danny starts to panic and realizes he has a choice to make: happiness or basketball.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 411

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Readers love the Tales from Foster High series by JOHN GOODE

Tales from Foster High

“This story was awesome. You could really get behind the feelings these young men had for each other and their lives in their small Texas community.”

—Mrs. Condit & Friends Read Books

“Brilliant. A truly phenomenal piece that took me right back to the halls of my youth, and made me remember the reality of what it was like.”

—Rainbow Book Reviews

End of the Innocence

“John Goode writes one hell of a book. His way with words is just almost sensual. He weaves not just a story, but threads that seem to wrap around your entire being.”

—Gay Romance Writer

“It is easily one of the most outstanding examples of realistic Young Adult fiction I’ve ever had the pleasure to read.”

—The Novel Approach

“You have to read this novel. Its twist and turns will leave you wanting more.”

—MM Good Book Reviews

151 Days

“This book and this series is important to read to really understand what some kids are going through in high school.”

—Hearts on Fire

By JOHN GOODE

First Time for Everything (anthology)

Going the Distance

LORDSOF ARCADIA

Distant Rumblings

Eye of the Storm

The Unseen Tempest

TALESFROM FOSTER HIGH

Tales from Foster High • To Wish for Impossible Things

End of the Innocence • Dear God

151 Days

Published by HARMONY INK PRESS

http://harmonyinkpress.com

COPYRIGHT

Published by

HARMONY INK PRESS

5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886 USA

[email protected] •http://harmonyinkpress.com

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of author imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Going the Distance

© 2014 John Goode.

Cover Art

© 2014 Paul Richmond.

www.paulrichmondstudio.com

Cover content is for illustrative purposes only and any person depicted on the cover is a model.

All rights reserved. This book is licensed to the original purchaser only. Duplication or distribution via any means is illegal and a violation of international copyright law, subject to criminal prosecution and upon conviction, fines, and/or imprisonment. Any eBook format cannot be legally loaned or given to others. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact Harmony Ink Press, 5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886, USA, or [email protected].

ISBN: 978-1-63216-619-7

Library Edition ISBN: 978-1-63216-620-3

Digital ISBN: 978-1-63216-621-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014949324

First Edition November 2014

Library Edition February 2015

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This is dedicated to every single gay athlete who played even though they knew their teammates might not accept them.

CHAPTER ONE: TIP-OFF

MYNAMEis Daniel Devin Monroe, and I’m eighteen years old.

I was born on January 24 in the Naval Hospital at Camp Pendleton to John and Mary Monroe, who had been married for only six months at the time. My dad was a newly minted PFC fresh out of boot and spent exactly three days with me as an infant before being shipped out. Later that month Mom and I joined him at Kaneohe Bay in Hawaii, where we lived until I was five years old and she was killed.

A drunk driver blindsided her on her way back from the store just outside of base. I was being watched by family friends on base and had no idea what had happened until a chaplain came to collect me. My father was deployed when it happened, and it took the brass almost a week to get him back home. Neither of them had any relatives living nearby, so I stayed with a family on base. It was the longest week of my life. I was pretty sure my parents had given me back. I cried, screamed, begged the people watching me to tell Mommy and Daddy that I would do better if they gave me another chance. No one wanted to be the guy who told a kid his mom was dead, so instead they kept trying to reassure me that I hadn’t done anything wrong.

To this day I walk around feeling like I have done something wrong even when I haven’t.

I can vaguely remember my dad standing there in his uniform, sobbing violently as they gave him the details of what had happened. Up to that moment I’d had no clue how bad the situation was. I thought Mommy had gone to Daddy and they were leaving me forever. Seeing him break down was the instant I knew our life as it had been was over. That might seem like a very complex thought for a five-year-old, but little kids see and understand more than a lot of adults think. I knew that Mommy was gone and she wasn’t coming back.

After that I don’t remember much besides an endless stream of covered dishes from the other families on base and the nights lying awake in my bed hearing my dad cry in the next room. I didn’t know it at the time, but my dad’s life was crashing around him also. He was the sole caretaker of a child he barely knew. I never asked him if he had the desire to send me off somewhere else to live. I knew he had a sister he never talked to, so it wasn’t like he didn’t have options. I never asked him because I was always afraid of the answer. I’m sure he was given the chance to get out of the service, but he didn’t take it. He was twenty-three years old, a widower raising a child on his own, and I figure he didn’t want to add “unemployed” to the words that described him.

We moved around a lot after that. The Marines assigned him to mercy billets, which were postings in CONUS—Contiguous United States, meaning the lower forty-eight—he could fill while raising me. We never stayed anywhere more than a year and a half. The only housing I knew was on base. I grew up with a high and tight and an oversized USMC sweatshirt on wherever I went. I was a base brat in a bad way, and it never occurred to me that people lived any differently than I did.

When I was ten, Dad sat me down and explained that we had a chance to transfer to Germany for an actual posting. The Marine Corps had been more than patient with him, and he repaid them with what would become a willing lifetime service commitment. Five years was a long time to not have a steady post, and at ten I was more than old enough to weather an overseas billet. My dad was now an MP, and there was a posting in Stuttgart he could take, providing I was okay with it. I didn’t understand at the time what going overseas meant or why he was asking me for the first time if I wanted to go somewhere. I simply agreed, thinking being in Germany meant another base school I wouldn’t like in a new place I’d never see.

I have never been so wrong about something before or since.

The thing about military bases is that they have a consistency that is comforting to a young child in ways an adult can’t understand. I never learned the difference between Oklahoma and Virginia, since the bases in each state looked exactly the same to me. The same steel gray tones coupled with the overwhelming sense of order made me oblivious to the concept that one place could be different from another. So when I stepped off the plane in Germany and was, for the first time in my ten years of life, confronted with something new and not the same as everything else, I did what any world-wise child would do.

I threw a fit and screamed, begging to go home.

The sad part was, I had no idea where home was. Home was a series of half a dozen names sprinkled across the country. Home was the identical four walls that made up my bedroom in each place. I was a military gypsy and was crying for a place that didn’t exist. I couldn’t verbalize to my father what I wanted. I’m sure he knew he was screwed. He had committed himself to the posting, and there were no other options. The Marines had given him more than enough leeway, and now it was his time to pay them back. The feelings of a ten-year-old had no impact whatsoever in their feelings, and he’d known me long enough by then to deal with me as best he could. In Germany.

On the other hand, I felt my dad was unfair, a jerk, and doing this just to make my life miserable. I hated the base, the school, the other kids who lived there, everything. My level of loathing knew no bounds. As time passed the loathing just increased. The first month sucked, since my dad had an inordinate amount of training and paperwork to complete in order to be brought up to speed with his assignment, which meant the horrible place with nothing on TV was made even worse by the fact I had to suffer it alone.

I hated the people who lived there, and I hated the weird language they spoke. I hated the different uniforms people wore on base, and I hated that we had to learn different things in school. I had gone from being an average student to the slow guy overnight when I found the difference between US-based schools and German schools to be devastating. I didn’t want to learn about Europe or Germany or anything new. I hated it more and more and blamed my dad for landing us in Stuttgart. I became surly, mouthing off to teachers, refusing to do schoolwork, generally being a spoiled fucking brat of the highest order. I say that now, looking back at how impossibly hard it must have been for my dad. He spent a twelve-hour shift in a new place with different regulations and a different culture and then came home to me and my problems. Me not liking the school and hating the language and not having good TV programs must have seemed petty to him.

If anyone knew life was not fair, it was my dad. He had been cheated out of a lifetime with my mother because one idiot asked for another round before leaving the bar that night. He had been forced not only to be a Marine but to be a single parent as well, and there was nothing he could do about it. My father knew very well life was not fair, and hearing the fact proclaimed loudly and often by a child who had no concept of what unfair meant must have been excruciating.

Around then we started fighting.

We had always gotten along before, and this was new territory for us. I had done what he said without complaint, and he had never felt the need to raise his voice at me. In Germany, things changed. I hated him for stranding me there, and he hated me for blaming him. Every night we would end up in a screaming match that more times than not included something getting thrown at a wall or the floor in anger and/or frustration. Things devolved into not talking at all, which didn’t make the feelings subside, of course. I began to wander around the base instead of going home after school, hoping in vain to find some part of this alien world that might seem normal even for a little while.

That was when I met them.

To say they were cool kids would be an insult to people who are truly cool. They were simply other kids. They were older than me, which meant they were automatically better in every way. A few belonged to the civilians who worked on base; others were fellow military brats who hated Stuttgart too. They had longer hair, cursed, and smoked constantly, which was a trifecta of epic to me. They hung out near the bowling alley just outside the base perimeter, their frayed jeans cuffs rolled up while they tried desperately to look apathetic about everything. I was tall for my age; in fact I was a freak for any age. At eleven I was almost six feet tall and looked like an oversized puppy with huge ears and feet I constantly tripped over. I was horribly skinny in a really noncool way. I was all elbows and ribs and no matter how much I ate, I only grew taller and stayed scrawny.

I’m not sure if they knew how young I really was and didn’t care, or if they had mistaken me for their age, but either way they accepted me into their little group. I pretended to smoke by dangling a cigarette out of my mouth and made “fuck” every other word in my sentences to be like them. They seemed to think I was funny as hell. My dad, on the other hand, didn’t. He forbade me to hang out with them, but because he was on duty for half the day, he had no way to keep an eye on me.

As we approached the end of our first year in Stuttgart, I had learned to inhale properly and knew every word you could never say on television plus a few that wouldn’t even make it into movies. We were a pack of rabid dogs thinking we were wolves wandering the base at dusk. We had no money, no vehicle, and no idea what to do.

I don’t know if you know the formula for figuring how stupid a group of teenage boys is, so let me share it with you. Take the average IQ, which is going to be abnormally low because of hormones, and then begin to divide that by each additional boy present. So basically the more boys in a group, the dumber we become, and let me tell you, we were pretty stupid to begin with. The leader was Joshua, and I thought he was the shit. He had this rat tail that screamed rebellion, along with a set of prepubescent biceps that to an eleven-year-old looked like massive guns. I followed him around like I had a crush on him. And, I was beginning to realize, that wasn’t too far off the mark.

Nothing was more sacred on a Marine base than a girl, a Marine’s daughter doubly so. If you want to see how dangerous a Marine can be, just look at his daughter. I mean it. Don’t flirt or even talk—just glance over at her. I assure you it will be the last thing you ever see before he kills you, most likely with his thumbs. So I never had a chance to interact with the opposite sex, and to be honest I never felt the need to. I grew up around men and liked their company. It wasn’t until that summer that I realized how much I liked it. Joshua was my first clue. In my eyes, he could do no wrong. The others laughed off the way I followed him around and called it hero worship, but I think he knew better. He was always grabbing my head and giving me noogies that lasted too long and never seemed to hurt like the ones the other guys gave me did. We spent a lot of time at his parents’ place playing video games, sharing a chair that barely fit the two of us.

It was cramped, but we never complained; in fact, we seemed to relish the contact.

My father, realizing that nothing short of sending me stateside would get me away from the guys, gave up trying to convince me to stay away and instead kept as careful a watch as he could on us. That is to say he wasn’t able to watch us at all. When my dad was on duty, Joshua and I would go to my place, and we’d sit in front of the television and watch the weird TV shows as long as we could until boredom kicked in. Eventually he’d launch a sneak attack that I had spent all afternoon waiting for and wrestle me to the ground. There was no point in struggling, since he was obviously stronger than I was, but it never seemed to be about who would win but about the contact.

We both spent more time grinding against each other than trying to get free, and on some level we both knew it. At first he spent a long time watching to see if I would protest or say something about it later. When I didn’t, the pretense that we were wrestling went away. He’d hold me down as he lay over me, pushing his jeans against mine. I didn’t understand what we were doing, but it felt good, and that was enough for me. I guess you can say I fell in love with Joshua that summer, even though I didn’t have words for it. He was everything I wanted to be. But what I was feeling was more than that, and it confused the hell out of me. Again I assumed everyone felt this way, but Joshua didn’t talk about what we did and pretty much treated me like he always had when we were with the other boys; I figured that was the way older kids handled the subject.

When I spent the night, I would make up a bed on the floor and wait until the lights were out and his parents had forgotten about us before climbing into his bed. Things were different at night under the covers in just our boxers. What was a physical struggle became something else as we held each other, feeling the heat come off our bodies. I had never felt like this, and for the first time since we moved there, I began to find something to like about it. He would whisper to me in the night, secret things that no one else knew, and I loved it. About how much he liked me and was glad we were friends. He seemed to marvel at the fact I was taller than him, and in fact almost as tall as his dad, yet younger then he was. He was also the first person to inform me that everything about my body was larger than normal.

Since my dad and I rarely talked about anything personal, I had never even thought that anything on my body might be above normal. I cursed my height, since it did nothing to benefit me and only served to make my life worse than it was. I couldn’t run without tripping, I was always noticed by strangers passing by, and buying clothes was embarrassing, since I could never shop in the kids’ section. But there, in the safety of the night, Joshua told me my size was not only good but, when it came to my dick, incredible. It was impossible to hide anything in my boxers normally; when I was hard, I might as well have been naked. He seemed to get great pleasure from rubbing me through the sheer material, and I know I loved it.

I wonder what my life would be like if his dad had never walked in on us that night. Would I have learned to like Germany? Would I have calmed down some and begun to forgive my dad? Would I have realized the crush I had on Joshua wasn’t normal and that, therefore, I wasn’t normal? Would I have known to keep that information from my dad as long as possible, therefore avoiding the eventual blowup for a while longer?

It didn’t matter, because when Joshua’s dad walked in on us, my world came crashing down around me again.

Joshua, knowing what we were doing was in no way acceptable, handled the shock better than I did. He jumped back as if waking up, screaming at me to get away from him. I just lay there stunned, my erection throbbing for both of them to see. His dad hauled me out of the bed with one arm. I think we were both a little shocked to find I was almost looking him in the eye when I stood up, but he reacted better than I did. He told me to get dressed, and then he called my dad. It was only at that point I knew how much trouble I was in.

I began to cry while I waited for Dad to show up. Every time I looked at Joshua, he would look somewhere else. His dad paced the living room, glaring every so often at me as he sighed and shook his head. His mother, who, up to this point, I’d thought of as a great lady, just sat on the foot of their stairs and seemed to be trying to push this all away by sheer force of will. I had stopped actually crying and instead just sat there in misery when a knock came at the front door. I felt my chest constrict, and I began to cry again. I looked over to Joshua with pleading eyes as his dad explained to mine what had happened. Joshua’s eyes were red too from his own tears, and he looked like he was almost ready to say something when we both heard my dad roar, “He did what?”

Joshua looked away, inching another couple of steps toward his room.

I had never felt smaller or more vulnerable than when my dad pushed past Josh’s dad and stormed into their living room. I refused to look away as he glared down at me, silently asking me if what he had just heard was true. When I looked down in shame, he knew it was. “Get your ass off that couch. We’re going.” His voice was almost a growl, and for the first time in my life, I was actually afraid of my father.

He had walked, since the on-base housing was all in the same general area. I walked out of the house with him close on my heels. I noticed my dad couldn’t make eye contact with the other dad now, so great was the shame I had brought to us. He was too quiet on the walk back to our house. I thought the silence was ten times worse than any screaming he could have been doing. Dread of what was coming made what was normally a short walk seemingly take forever, which wasn’t all bad because I didn’t want to know how it ended. The second I crossed the threshold, I ran for my room, but I got maybe three steps before he grabbed the back of my shirt, hauled me back, and tossed me into the living room.

I hit the carpet and scrambled to my feet as he came at me. His voice was like something on high, and it blasted through me when he bellowed. “Did you do what he said you did?” I cringed and backed away from him. “Were you touching him in his sleep?” The loathing in his voice was the worst thing I had experienced in my entire life. I felt a fresh wave of shame sluice over me, and I started to tremble inside. When I didn’t answer, his voice became louder. “Why would you touch another boy like that?” Another wince from me, and I was pressed up against the back wall, still trying to make myself smaller. “You know who does that? Perverts. Are you a pervert? Is that what you want to grow up to be? Some creepy guy who touches other boys while they sleep?”

“He wasn’t asleep!” I snapped back in what I can only explain as a moment of temporary insanity. When I saw the disbelief in my dad’s eyes, I argued even harder. “He wasn’t sleeping!” I took a sobbing breath and said, “He started it!”

That was the first time my dad hit me.

I know it sounds hard to believe, a single military dad who was all about order and discipline never once spanking his son, but my dad never had to. His voice and authority had always been more than enough to keep me in line. I couldn’t blame him—that entire summer with me skipping school, hanging out with those boys, smoking, and now this. He was at the end of his rope, and he didn’t know what else to do. I justify his actions because he has never hit me again. We were both a little crazy that night, and when he slapped me, it wasn’t the physical impact that caused me pain. The gunshot-like crack of flesh on flesh didn’t startle me. It was the fact that looking into his eyes, I could tell he didn’t know why he had done it either. We were both feeling betrayed, and neither one could fathom where we had gone wrong enough to warrant hitting me.

I held a hand to the reddening welt on my cheek and just shook as he hovered over me with his hand raised for another blow. I don’t know if it was the very real fear in my face or the fact he had just lost control that stopped him from continuing. All I knew was that he froze in place for a few seconds, which were enough for me. I dashed around him and made a beeline for my room, slamming and locking my door behind me. This time when I broke down and began to cry, it wasn’t from shock, fear, or even pain.

I was crying from disgust.

I didn’t know what kind of a person I had become. I liked something as gross as touching another boy, and I knew it wasn’t right. Fag, queer, homo, and gay: these were all well-known insults to a kid my age, and no one ever used them in a good way. I was all those things, which logically meant I was a bad person inside. As I lay there on my floor, blocking my door, I cried myself to sleep, consciously thinking for the first time in my life that I was never going to be a good person.

The next thing I remember was a soft knocking on my door and sunlight streaming through my windows. “Danny?” my dad’s voice called from the other side as the doorknob rattled. “Unlock the door.” He sounded as tired as I felt. I unlocked the door, and he stood there, looking at me with an expression as unreadable as any I had seen on him before. “Get dressed,” he ordered before walking away.

I knew better than to ask where we were going. I simply closed the door and pulled on a pair of jeans and a sweatshirt, knowing last night was not over. He had his keys in his hand, which meant our destination was outside the base. I began to worry as we drove and wondered if I was going to ralph in the car. I wanted to ask where we were going, but he wouldn’t even glance at me, and I didn’t have the guts to ask without a prompt. We exited the base, and the fear was well on its way to becoming sheer terror as he drove us into town.

When you’re a kid, the rules of society are a little fuzzy. Whether or not a parent had the ability to leave a kid on the side of the road without explanation wasn’t a black-and-white thing. I had flashbacks to when my mom had died, that feeling I was going to be returned because I was defective. And even though I was pretty sure I knew where babies came from so there wasn’t a place you could return them to, I was still terrified that was what he was about to do. I was hungry, tired, the side of my face ached, and I felt on the verge of tears again. We pulled up to what looked like a gymnasium, and I felt lost. He stopped the car and sat for a moment. He looked as if he were weighing a difficult situation and didn’t like his choices.

I was sure he was going to sell me off or just ditch me somewhere in the middle of Germany. What could I do? I didn’t speak the language. I didn’t know how to get back to base. I had no money and no means to make any. I would be dead within a day, wild dogs feeding on my carcass as I huddled behind some trash cans in the middle of the night. Of course I didn’t even know if there were wild dogs in Germany, but I’d seen a documentary in the States once, and the thought of something so benign ending up so feral had petrified me. After about a minute, he took the keys out of the car and opened his door. I followed, pretty sure he wasn’t going to abandon me in the car. He liked the car.

He spotted an empty bench just to the left of the gym door and sat down and pointed, first at me and then at the bench. I sat next to him. “You have a choice to make,” he said, still not looking at me. “I can do two things with you, and I’m going to leave it up to you to decide.” I felt the tears welling up again but forced myself to stay steady. “You can go back to the States,” he said. “I talked to your Aunt Kelly, and she said you could stay with them if you want.” He turned to stare at me. “But if you go, you aren’t coming back here. I have another three years in Stuttgart, and other than maybe Christmas, I won’t have any way to get back to Texas.” I could feel the world falling from underneath me and realized Dad wasn’t going to ditch me. He was going to send me off to live with his sister, a woman he described on his best days as a raging bitch. She had three daughters, and each was more self-centered and superficial than the next. I hated their family, and my dad knew it. We barely saw them, and the few times we had, I had literally begged my dad to leave when we were alone, a sentiment he never argued with. The wild dogs and being alone in a strange country sounded better than that.

After a second of letting that soak in, he said, “Or you can change.” That brought me up short, since I didn’t understand. “You go to school, stop fucking around, clean up your act, and find something else to do with your free time besides be a punk.”

“Like what?” I asked, not really knowing what else I could do besides be the loser I had been the past year.

He gestured behind me at the gym. “They have a youth basketball league here. You’d need to be here four days a week, take the bus from the base and back. There is a lot of practice, working out, and learning the game as well as building teamwork skills.” I looked back at the building, wondering how such an ugly place had all that inside of it. “You hold down a B average, prove to me you can stick at something, and you can stay.” Our eyes locked as I realized this was the moment where I had to choose. “You screw up once, and I’ll send you to Kelly’s so fast your feet won’t even touch the ground before you hit the States. So think about it, because if you don’t plan on trying, you might as well as leave now and not waste anyone’s time.” I knew tears were streaming down my cheeks, but I couldn’t stop them. “What’s it going to be?”

The emotion became too much, and I buried myself into his side as I really began to bawl. “I’m sorry!” I exclaimed into his shirt as I felt his arm move around me. “I want to stay. Please don’t send me away!” And I meant it. I still hated Germany and the base and everything about it, but I loved my dad more, and the thought of living the rest of my life with him so far out of reach was the worst thing I could think of. “I’ll do better,” I promised as I held on tight to him. “I won’t let you down again.”

And though I was only a miserable eleven-year-old boy, I meant what I promised with every fiber of my being. I would never again in my life do anything to shame this man who had spent so much of his own life raising me. I had stumbled, but I wasn’t down, and I was willing to do anything to make it up to him, and in this case, it meant basketball. The game and my redemption were so closely tied together that basketball was never once a mere game as far as I was concerned. It was a faith, a belief that through it, I would be reborn as a better person. Some people come to that concept through Jesus or through AA, but I came to it through basketball. It was the path I could never stray from lest I lose my dad and his love. It became more than my life; it was my soul.

And has been ever since.

CHAPTER TWO: CHECKINGTHE BALL

THENEXTthree years passed by in a blur.

My life became a routine of waking up before the sun had risen, taking a shower, and heading out the door. I’d run around the base before school, sometimes with my dad, more times by myself. I had stolen an old Walkman of his, and though there was precious little on base in the way of cassettes, I learned to get by on my dad’s stockpile of eighties music. I’d get home, take another shower, and then eat everything I could find in the house. Then I’d sit in class and do my best to not nod off as I waited until two o’clock in the afternoon when class let out. I’d run to the bus stop and catch the 2:15 to the gym, where my day truly began. We’d change out and do laps around the gym until we started to work up a sweat. Then we started with drills. For those not versed in the fine world of basketball training, allow me to explain.

When you perform a certain skill over and over until it becomes second nature to you, you are doing drills. The key to being a good player isn’t being able to do something when you consciously want to. A good player is able to use a skill without deciding to. Passing, dribbling, shooting, you start to learn these individual parts of the game until you find yourself dreaming about them constantly. At first this is all you do—practice a pass, practice dribbling, practice another pass, practice your shooting. When the coach sees something only he can perceive in you, then you are allowed to actually play a game against other people.

That’s when it gets hard.

Playing against your own teammates is the weirdest thing you will ever do in basketball. Not only are you playing against guys who have watched you learn every move you make, but they have been trained in exactly the same way. The whole focus of learning the game isn’t about who wins or loses. It’s about how well you play. Make a basket through sheer luck, and you’ll get berated. You should always know where the hoop is no matter where you are; sheer luck doesn’t mean anything. Steal a ball from a guy, and you’ll hear a lecture on the guy’s sloppy form and the reassurance that the next guy you try to steal a ball from won’t get caught napping. It sounds horrible, and let me assure you, it is.

The funny thing is that you never notice you’re getting better.

You’re with the same group of guys all the time, and you all evolve at the same rate, so there is never this flash that you know more than anyone else. It wasn’t until I had been practicing for about a year and a half and played a pickup game on base that it dawned on me that I knew what I was doing. It was a three-on-three with a few of the older kids, none of them from Joshua’s crew, who would never be caught dead engaging in something as lame as exercise. They’d asked me to play because I was a few inches over six feet at the time, not because they thought I had any talent. I was a body to stand on the court and fill in for the guy who hadn’t showed up and nothing more. I accepted, because it was a Sunday, and frankly I was bored out of my head looking for something safe to do.

Less than a minute into the game, I realized these guys sucked.

They had no form, no style. They were just running around the court lobbing air balls, praying Michael Jordan would answer and sink one for them. The first time the guy I was guarding had the ball, I took it from him so fast he was still moving forward by the time I was taking the shot. There are few sounds as rewarding as the sound of a ball swooshing into a net. It causes a Pavlovian response in my mind that gives me pleasure no matter where I am. When I turned around to see who was going to throw the ball in, I was surprised to see five other guys looking at me in shock.

The rest of the game went a lot like that.

The guy who was supposed to be my partner was ignored as the three other guys went after me with a vengeance. The game became more challenging, but they couldn’t stop me for long. If they’d known what they were doing or had a sense of teamwork, I’d have been fucked, but all they knew was to stand in front of me and wave their arms, hoping that would be enough to stop me. Every time I sank a three-pointer, they realized it wasn’t.

They never invited me again, but I didn’t care. I walked away from the court with a smile on my face and the knowledge there was something I excelled at. The extra knowledge that I had schooled three guys older than me only made it sweeter. I threw myself even harder into practice after that. I made the actual team my second year, and we ended up winning the local tournament, solidly beating thirteen other teams. The next year I made the equivalent of varsity, and we went up against a whole other class of teams.

We ended up ranking third in league, which was the highest our gym had ever ranked. That was when the coaches talked to my dad. I was oblivious to the conversations, of course, but I found out later that they told him they had taught me all they could. They told him I had a gift, not just my height, and that I had a chance to do something more than just play the game for fun. I always wondered what went through my dad’s mind. Did he not believe them? Did he ask them to make sure they had the right dad? Did he wonder if that talent had been wasted on someone like me?

Since I didn’t know about the conversation, I didn’t know about his thought process, but I do know what happened next. His tour was about up, and that put him at the fourteen-year mark, so we both had a big choice ahead of us. He sat me down to have A Talk, which so far had never been a good experience. The first had brought us to Germany and the second was the threat to send me home, so I didn’t have high hopes about the third one. He asked me if I liked Germany and the base, which was more asking me if I had learned to stop hating it. Again, I never found out his thought process, but I’m sure “I love basketball” must have been the answer he was looking for.

He re-upped with a transfer to Texas, a promotion training the security forces on a naval base. I had mixed emotions about leaving Germany that fall. I hated the base because now I hated Joshua and what he had done to me. We’d never talked again, though we saw each other from a distance. Every time I saw him, I had the same strange feeling in my stomach I’d had when we were friends, so I always stayed away, knowing nothing good would ever come from going down that path. On the other hand, I loved basketball in a way I wouldn’t have thought possible. I knew there was basketball in the States, but I was afraid at the thought of having to start all over again. Frankly it scared the hell out of me.

I was fifteen, no longer the spoiled brat who had walked off the plane five years earlier. I could look back and see I had never given the place a chance. My own fucked-up little drama had spoiled me for any chance of seeing how nice a country it might have been. No matter how much I may have not enjoyed my time in Stuttgart, though, I had to admit that being in Germany had introduced me to the one great love of my life. The plane took off, and I felt sad as we said good-bye to Germany forever. I didn’t know why I felt that way, but I knew subconsciously the place had revealed more about who I really was than I cared to see. On one hand I was sad about all I was leaving; on the other I was relieved about all the things that wouldn’t remind me of my past. Now I knew what was inside me. It was my duty to try to keep it under control.

When I fell asleep, we were in Europe. When I woke up, we were in Texas. That was how fast my life changed. We switched concourses and planes in Dallas, and I instantly knew I was back in the States. I had thought I’d known the difference when I was away, but as we walked through the crowded terminal, it was blatantly obvious to me. People were more insular, closed off, lost in their own little world. I understood now how foreigners could see us as rude in comparison. We waited in the USO lounge for our connecting flight, and I could tell my dad was feeling it too.

It’s an odd sensation being a stranger in your own country. I noticed there were more than a few good-looking girls walking through the airport. My dad noticed more than a couple had stared at me. “You don’t look fifteen,” he said once we’d grabbed some food and settled in front of the TV.

I was in midbite of a hot dog and looked over at him. “Is that a bad thing?” I asked, trying to swallow the mouthful whole.

“Depends on who you ask,” he said with a smug smile.

“I’m asking you.”

He looked back and, though he was obviously having fun with me, as always there was a deadly serious tone in his voice. “Ask the guy who got a girl pregnant at seventeen and had to join the Marines to support her, and he’d say no. Ask the guy who is amazed at the man his son is becoming, and he’d say yes.” He took a drink as my mind tried to wrap itself around the compliment. “Ask your father, and he’d say you’re too young for sex.”

He laughed when I blushed.

We boarded a much smaller plane for the last leg of our flight. Unlike the massive jets used on international flyways, the plane we clambered into was a two-prop baby; I wondered if it could even take off. The flight from Germany had been packed; there were only five people including us on this flight. I was too tired to realize that the plane’s size and passenger load were the first warning signs about where we were headed. I adjusted my seat belt and looked over at my dad. “Where are we going again?”

“Corpus Christi. They have a naval base there,” he explained.

“Is it a big town?” I asked.

“Define big.”

“Like Norfolk?” I offered. He shook his head no. “Like K Bay?” Another no. “Like Jacksonville?” He thought for a moment and then said, “Yeah, like that.”

“How big is the base?” I asked as we prepared for takeoff. And then I quickly asked the real question. “How many kids go to school there?”

My dad didn’t even look over at me as he replied, “You aren’t going to school on base. I enrolled you in a civilian school.”

As the plane accelerated, I felt my stomach drop, and it had nothing to do with the motion.

If you’ve gone to public high school, I’m sure you have no idea where my reaction came from. After all, you were used to walking into a strange school with sometimes thousands of kids who didn’t know you. You thought it normal. You were raised to understand how to talk to new kids, get to know them, and then eventually make friends out of some of them. It had always been something of a mystery to me how other kids did it. On base we were all like prisoners of war and had no choice but to know each other. It didn’t matter what you wore or how you talked, because in the end we were all stuck there on base until our parents got transferred somewhere else. It made for socializing quickly, but at the same time you didn’t make very deep friendships, since we all knew it was just for now anyway. Joshua and his crew were the closest I had ever gotten to friends, and look how that turned out. I was the only base kid who played basketball at the gym, which meant I got to see the rest of the team every practice or game, but after that I headed back to base while they headed back to their homes in Stuttgart.

I had never had friends, and that fact dawned on me while we were making the hop to Corpus Christi.

I know it sounds stupid, but when everyone else you know is in the same boat, you don’t think about how deep the water is until you fall overboard. A new school, a new team, a new everything was just about as terrifying a thought as I could imagine. What if I dressed wrong? What if I talked wrong? What if I was a nerd? What if they could tell I’d once fooled around with a guy? As the plane chugged its way toward Corpus, I felt a very real panic start to well up in my body. What was already a small plane became microscopic, and though I was taller than anyone on it, I thought the seats were shrinking under me. This is what Alice must have felt like when she ate the cake, the entire world falling away as she sat completely still.

“You okay?” my dad asked, noticing my hands were now claws holding fast to the armrests. I looked over at him, trying to keep my cool about me, but from the way his eyes got wide, it was pretty obvious I failed at that. “Danny, what’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” I said in a very small voice.

He continued to stare at me, which made me even more nauseous than the turbulence. My dad was a person who was constructed from different types of strength. If he had a weakness, I’d never seen it. So to me showing any fear in his presence was the equivalent of letting him down. But only a blind man could have missed how I had grown pale and was sitting there shivering in a cold sweat. He put one hand over mine and leaned in. “Are you scared about school?”

My voice actually cracked as I responded with “Who’s scared?”