Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

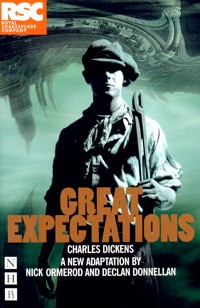

A gritty adaptation of Dickens' least sentimental love story with a cast of some of his most unforgettable characters. Whilst at his parents' graveside, Pip is accosted by Magwitch, a convict escaped from one of the prison ships. Terrified, he is forced to help the man to get away. An unexpected invitation to the house of rich old Miss Havisham forces him into the path of her beautiful, cruel niece Estella and their strange, ruthless games. After an anonymous benefactor grants him a small fortune, Pip turns his back on his humble life as a blacksmith's apprentice – he moves to London to become a gentleman in the hopes of winning Estella. But he has no idea of the dangers that await him there, or from where his salvation will come. This adaptation of Charles Dickens' Great Expectations, by Nick Ormerod and Declan Donnellan, was first performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, in 2005.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 127

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Charles Dickens

GREATEXPECTATIONS

adapted by

Nick Ormerod and Declan Donnellan

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Original Production

Characters

Act One

Act Two

About the Authors

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

For Jane Gibson

This stage adaptation of Great Expectations was first performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company in association with Cheek by Jowl in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, on 25 November 2005, with the following cast:

PIP

Samuel Roukin

YOUNG PIP

Harry Davies/Jack Cheesbrough

MRS JOE

Sophie Duval

MAGWITCH

Roger Sloman

JOE GARGERY

Brian Doherty

PUMBLECHOOK

Julius D’Silva

MR WOPSLE/ORLICK MR HUBBLE/

Tobias Beer

BENTLEY DRUMMLE

Philip Cumbus

MRS HUBBLE

Gwendoline Christie

COMPEYSON

Adam Newsome

BIDDY

Emma Lowndes

YOUNG ESTELLA

Jo Woodcock

MISS HAVISHAM

Siân Phillips

YOUNG HERBERT POCKET

Jack Fielding/George Haynes

JAGGERS

Richard Bremmer

WEMMICK

Jem Wall

HERBERT POCKET

Robert Hastie

STARTOP

Philip McGinley

MOLLY

Ruth Everett

ESTELLA

Neve McIntosh

WATCHMEN

Joseph McNab

All other parts played by members of the company

Director

Declan Donnellan

Designer

Nick Ormerod

Lighting Designer

Judith Greenwood

Composer

Catherine Jayes

Sound Designer

Gregory Clarke

Characters

in order of speaking

MAGWITCH

YOUNG PIP

MRS JOE

JOE GARGERY

PUMBLECHOOK

WOPSLE

MR HUBBLE

MRS HUBBLE

SERGEANT

COMPEYSON

YOUNG ESTELLA

MISS HAVISHAM

YOUNG HERBERT

JAGGERS

PIP

ORLICK

BIDDY

PETITIONERS

WEMMICK

HERBERT POCKET

DRUMMLE

STARTOP

MOLLY

ESTELLA

BEADLE

WATCHMAN

LITTLE MAGWITCH

COUNSEL

OFFICER

WARDER

BAILIFFS

The part of Pip is divided into Pip (about twenty years old), and Young Pip (twelve); that of Estella into Estella (about twenty), and Young Estella (twelve); that of Herbert into Herbert (twenty), and Young Herbert (twelve). The part of the Chorus is divided between the whole company.

ACT ONE

The whole company come onto a bare stage.

CHORUS. My father’s family name being Pirrip,

CHORUS. and my Christian name Philip,

CHORUS. my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than . . .

CHORUS. Pip!

CHORUS. So, I called myself

CHORUS. Pip,

CHORUS. and came to be called

CHORUS. Pip.

CHORUS. Ours was the marsh country,

The scene opens up to show a distant flat horizon.

A graveyard.

CHORUS. down by the river, within twenty miles of the sea.

CHORUS. My first most vivid and broad impression of the identity of things seems to me to have been gained on this memorable raw, Christmas Eve afternoon towards evening. I found out for certain,

CHORUS. that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard;

CHORUS. and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana, wife of the above, were dead and buried;

CHORUS. and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard was the marshes;

CHORUS. and that the low leaden line beyond was the river;

CHORUS. and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea;

CHORUS. and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry was Pip.

MAGWITCH appears from behind a gravestone.

MAGWITCH. Hold your noise! Keep still, you little devil, or I’ll cut your throat! Tell us your name. Quickly.

YOUNG PIP. Pip, sir.

MAGWITCH. Once more. Give it mouth!

YOUNG PIP. Pip. Pip, sir.

MAGWITCH. Show us where you live. Point out the place!

PIP points. MAGWITCH grabs his ankle, turns him upside down and shakes him. A crust of bread falls out of a pocket. MAGWITCH eats it ravenously.

What fat cheeks you ha’ got. Darn me if I couldn’t eat ’em too. Now lookee here! Where’s your mother?

YOUNG PIP. There, sir!

MAGWITCH starts up. PIP points to the gravestone.

Also Georgiana. That’s my mother.

MAGWITCH. Oh! And is that your father alonger your mother?

YOUNG PIP. Yes, sir, him too; late of this parish.

MAGWITCH. Ha! Who d’ye live with – supposin’ you’re kindly let to live, which I han’t made up my mind about?

YOUNG PIP. My sister, sir – Mrs Joe Gargery – wife of Joe Gargery, the blacksmith, sir.

MAGWITCH. Blacksmith, eh? You know what a file is?

YOUNG PIP. Yes, sir.

MAGWITCH. And you know what wittles is?

YOUNG PIP. Yes, sir.

MAGWITCH. You get me a file and you get me wittles. You bring ’em both to me. Or I’ll have your heart and liver out. You bring the lot to me, at that old battery over yonder. You do it, and you never dare to say a word or dare to make a sign concerning your having seen such a person as me, or any person sumever, and you shall be let to live. You fail, or you go from my words in any partickler, no matter how small it is, and your heart and your liver shall be tore out, roasted and ate.

The Gargery parlour.

MRS JOE. Where have you been, you young monkey? Tickler wants to know. Tell me directly where you’ve been to wear me away with fret and fright and worrit.

YOUNG PIP. The churchyard.

MRS JOE. Churchyard! If it warn’t for me you’d have been to the churchyard long ago, and stayed there. Who brought you up by hand?

YOUNG PIP. You did.

MRS JOE. And why did I do it, I should like to know?

YOUNG PIP. I don’t know.

MRS JOE. I don’t! I’d never do it again! I know that. I may truly say I’ve never had this apron of mine off since born you were. It’s bad enough to be a blacksmith’s wife – and him (Indicating JOE.) a Gargery – without being your mother. Hah! Churchyard, indeed! You may well say churchyard, you two. You’ll drive me to the churchyard betwixt you, one of these days, and oh, a pr-r-recious pair you’d be without me!

A distant rumble.

YOUNG PIP. Was that the guns, Joe?

JOE. Ah! There’s another conwict off.

YOUNG PIP. What does that mean, Joe?

MRS JOE. Escaped. Escaped.

YOUNG PIP. What’s a convict?

JOE. There was a conwict off last night, after sunset-gun. And they fired warning of him. And now, it appears they’re firing warning of another.

YOUNG PIP. Who’s firing?

MRS JOE. Drat that boy, what a questioner he is. Ask no questions, and you’ll be told no lies.

YOUNG PIP. Where does the firing comes from?

MRS JOE. Lord bless the boy! From the hulks!

YOUNG PIP. Oh-h! Hulks! What’s hulks?

MRS JOE. That’s the way with this boy! Answer him one question, and he’ll ask you a dozen directly. Hulks are prison-ships, right ’cross th’ meshes.

YOUNG PIP. Who’s in the prison-ships?

MRS JOE. I tell you what, young fellow, I didn’t bring you up by hand to badger people’s lives out. It would be blame to me, and not praise, if I had. People are put in the hulks because they murder, and because they rob, and forge, and do all sorts of bad; and they always begin by asking questions.

MRS JOE cuts and butters bread.

CHORUS. Though I was hungry,

CHORUS. I felt that I must have something in reserve for my dreadful acquaintance.

CHORUS. Joe had just looked away and I got my bread and butter down my leg.

JOE stares in disbelief.

MRS JOE. What’s the matter now?

JOE. I say, you know! Pip, old chap! You’ll do yourself a mischief. It’ll stick somewhere. You can’t have chawed it, Pip.

MRS JOE. What’s the matter now?

JOE. If you can cough any trifle on it up, Pip, I’d recommend you to do it. Manners is manners, but still your elth’s your elth.

MRS JOE attacks JOE and tweaks his whiskers.

MRS JOE. Now, perhaps you’ll mention what’s the matter, you staring great stuck pig.

JOE. You know, Pip, you and me is always friends, and I’d be the last to tell upon you, any time. But such a – such a most oncommon bolt as that!

MRS JOE. Been bolting his food, has he?

JOE. You know, old chap, I bolted, myself, when I was your age – frequent – and as a boy I’ve been among a many bolters; but I never see your bolting equal yet, Pip, and it’s a mercy you ain’t bolted dead.

MRS JOE grabs YOUNG PIP by the hair.

MRS JOE. You come along and be dosed.

CHORUS. Some medical beast had revived tar-water in those days as a fine medicine,

CHORUS. having a belief in its virtues correspondent to its nastiness.

CHORUS. Joe got off with half a pint.

MRS JOE. Now, you get along to bed!

YOUNG PIP runs up the stairs. JOE and MRS JOE exit.

CHORUS. I was never allowed a candle to light me to bed

CHORUS. and, as I went upstairs in the dark, I felt fearfully sensible of the great convenience that the hulks were handy for me.

CHORUS. I was clearly on my way there.

CHORUS. I had begun by asking questions, and I was going to rob Mrs Joe.

CHORUS. As soon as the great black velvet pall outside my window was shot with grey, I got up and went downstairs.

YOUNG PIP reappears. It is now dark. He creeps down the stairs. A board creaks. He freezes.

CHORUS. Every board upon the way, and every crack in every board, calling after me,

CHORUS. Stop thief!

CHORUS. Get up, Mrs Joe!

CHORUS. I had no time for selection, no time for anything, for I had no time to spare.

CHORUS. I stole some bread,

CHORUS. some rind of cheese,

CHORUS. about half a jar of mincemeat,

CHORUS. some brandy from a stone bottle,

CHORUS. which I decanted into a glass bottle which I had brought for the purpose,

CHORUS. diluting the stone bottle from a jug,

CHORUS. a beautiful round compact pie

CHORUS. and a file from the forge.

CHORUS. I ran for the misty marshes.

CHORUS. It was a rimy morning and very damp.

CHORUS. The mist was heavier yet when I got out on the marshes, so that instead of my running at everything, everything seemed to run at me.

CHORUS. A boy with somebody else’s pork pie.

CHORUS. Stop him!

YOUNG PIP climbs a farm gate. A cow appears out of nowhere.

CHORUS. The cattle came upon me with like suddenness staring out of their eyes, and steaming out of their nostrils.

CHORUS. One black ox fixed me so obstinately with his eyes,

CHORUS. and moved his blunt head round in such an accusatory manner.

YOUNG PIP. I couldn’t help it, sir! It wasn’t for myself I took it!

CHORUS. Upon which he put down his head, blew a cloud of smoke out of his nose, and vanished with a kick-up of his hind legs and a flourish of his tail.

CHORUS. I had just crossed a ditch and scrambled up a mound when I saw the man sitting before me.

The gathering dawn reveals a MAN who is sitting on the ground with his back to him, and appears to be nodding off. He is dressed like MAGWITCH. YOUNG PIP touches him on the shoulder. The MAN leaps up.

CHORUS. It was not the same man. Another convict!

CHORUS. He ran off into the mist. I was soon at the battery, after that.

CHORUS. There was the right man.

YOUNG PIP lays his bundle down by MAGWITCH, who grabs it and begins to eat ravenously.

MAGWITCH. What’s in the bottle, boy?

YOUNG PIP. Brandy.

MAGWITCH takes a swig and then starts as if he’s heard something.

MAGWITCH. You’re not a deceiving imp? You brought no one with you?

YOUNG PIP. No, sir! No!

MAGWITCH. And nobody followed you?

YOUNG PIP. No! I’m sure he didn’t.

MAGWITCH. What did you say?

YOUNG PIP. The other man, dressed like you. I saw him over there. I thought it was you.

MAGWITCH. This man, did you notice anything about him?

YOUNG PIP. He had bruises on his face.

MAGWITCH. Where?

YOUNG PIP. Here on his cheek.

MAGWITCH. Where is he? Show me the way he went. I’ll pull him down.

He makes to go, but his chain trips him.

Curse this iron on my leg! Give us hold of the file, boy.

MAGWITCH starts to file furiously at his leg chain.

Go, go home, boy.

CHORUS. The last I saw of him, he was working hard at his fetter.

CHORUS. The last I heard of him, I stopped in the mist to listen, and the file was still going.

CHORUS. It was Christmas Day and we were to have a superb dinner,

The Gargery parlour.

Around the table, MR and MRS HUBBLE, PUMBLECHOOK, MR WOPSLE, JOE and MRS JOE and YOUNG PIP. All are eating.

CHORUS. consisting of a leg of pickled pork and greens

CHORUS. and a pair of roast stuffed fowls.

CHORUS. A handsome mince pie had been made yesterday morning

CHORUS. and the pudding was already on the boil.

PUMBLECHOOK. This pork, ma’am, is the finest I have ever eaten . . . especially, be grateful, boy, to them which brought you up by hand. (To audience.) Uncle Pumblechook. Joe’s uncle –

MRS JOE (to audience). but appropriated by Mrs Joe.

WOPSLE. There’s a subject! If you want a subject for a real sermon: look at pork! (To audience.) Mr Wopsle, the clerk at church, and an amateur thespian of some note.

PUMBLECHOOK. True, sir. Many a moral for the young.

MRS JOE (elbowing YOUNG PIP). You listen to this.

WOPSLE. Swine were the companions of the prodigal. The gluttony of swine is put before us, as an example to the young. What is detestable in a pig is more detestable in a boy.

MR HUBBLE. Or girl. (To audience.) Mr Hubble, the wheelwright –

MRS HUBBLE (to audience). and his wife, Mrs Hubble,

MR and MRS HUBBLE. but they have little consequence in our story.

WOPSLE. Of course, or girl, Mr Hubble, but there is no girl present.

PUMBLECHOOK. Besides, think what you’ve got to be grateful for. If you’d been born a Squeaker.

MRS JOE. He was, if ever a child was.

PUMBLECHOOK. Well, but I mean a four-footed Squeaker. If you had been born such, would you have been here now? Not you –

WOPSLE (pointing to the joint of meat). Unless in that form.

PUMBLECHOOK. But I don’t mean in that form, sir; I mean, enjoying himself with his elders and betters, and improving himself with their conversation, and rolling in the lap of luxury. Would he have been doing that? No, he wouldn’t. And what would have been your destination? (Turning to YOUNG PIP.) You would have been disposed of for so many shillings according to the market price of the article, and Dunstable the butcher would have come up to you as you lay in your straw, and he would have whipped you under his left arm, and with his right he would have tucked up his frock to get a penknife from out of his waistcoat-pocket, and he would have shed your blood and had your life. No bringing up by hand then. Not a bit of it!

MRS HUBBLE. He is a world of trouble to you, ma’am.

MRS JOE. Trouble? Trouble? I’ve brought this boy up by hand and he is nothing but trouble. His second name is Trouble.

They all stare reproachfully at YOUNG PIP.

Have a little brandy, Uncle.

CHORUS. O Heavens, it had come at last!

CHORUS. He would find it was weak, he would say it was weak,

CHORUS. and I was lost!

MRS JOE goes to the cupboard and pours out a brandy.

CHORUS. Pumblechook trifles with his glass –

CHORUS. looks at it through the light and throws his head back, and drinks the brandy off.

PUMBLECHOOK. Tar!

ALL. Tar!

General consternation. All look to MRS JOE. PUMBLECHOOK runs out of the the door.