Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Comprehensive Owner's Guide

- Sprache: Englisch

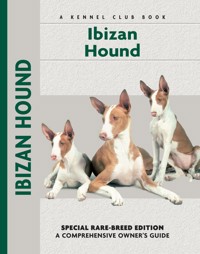

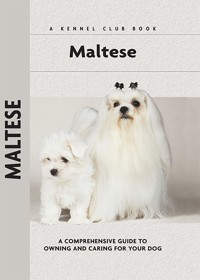

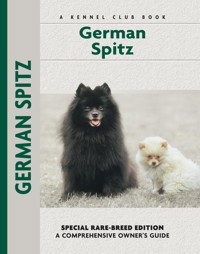

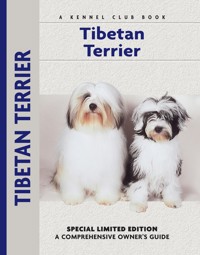

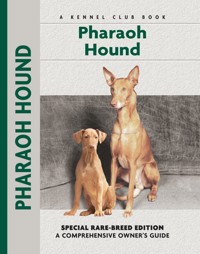

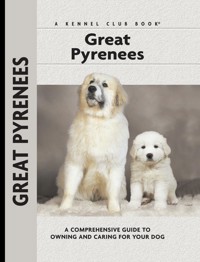

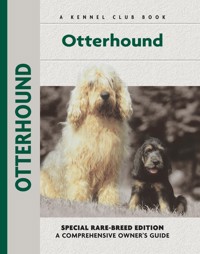

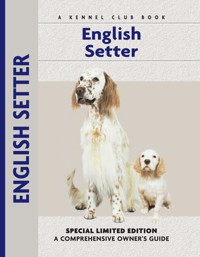

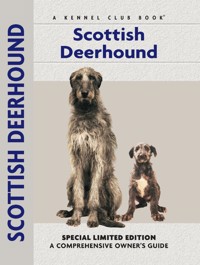

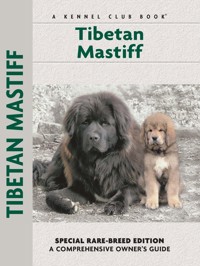

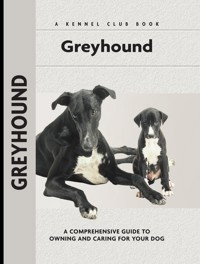

The experts at Kennel Club Books present the world's largest series of breed-specific canine care books. Each critically acclaimed Comprehensive Owner's Guide covers everything from breed standards to behavior, from training to health and nutrition. With nearly 200 titles in print, this series is sure to please the fancier of even the rarest breed!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 216

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Physical Characteristics of the Greyhound

(from the American Kennel Club breed standard)

Head: Long and narrow, fairly wide between the ears, scarcely perceptible stop, little or no development of nasal sinuses, good length of muzzle, which should be powerful without coarseness.

Eyes: Dark, bright, intelligent, indicating spirit.

Teeth: very strong and even in front.

Ears: Small and fine in texture, thrown back and folded, except when excited, when they are semi-pricked.

Neck: Long, muscular, without throatiness, slightly arched, and widening gradually into the shoulder.

Shoulders: Placed as obliquely as possible, muscular without being loaded.

Chest: Deep, and as wide as consistent with speed, fairly well-sprung ribs.

Forelegs: Perfectly straight, set well into the shoulders, neither turned in nor out, pasterns strong.

Coat: Short, smooth and firm in texture.

Back: Muscular and broad.

Weight: Dogs, 65 to 70 pounds; bitches 60 to 65 pounds.

Loins: Good depth of muscle, well arched, well cut up in the flanks.

Tail: Long, fine and tapering with a slight upward curve.

Hindquarters: Long, very muscular and powerful, wide and well let down, well-bent stifles. Hocks well bent and rather close to ground, wide but straight fore and aft.

Feet: Hard and close, rather more hare than catfeet, well knuckled up with good strong claws.

Contents

History of the Greyhound

Follow the breed’s long and varied history—from its ancient beginnings as a venerated sight hound, to valued hunter of British royalty, to competitive courser and racer, to increasingly popular companion and show dog known to fanciers the world over.

Characteristics of the Greyhound

The sleek, graceful lines of an athlete paired with the heart of a champion, the Greyhound is much more than just a racing dog. Meet the gentle, expressive and intelligent personality behind the physical beauty and learn why a growing number of people are choosing to share their lives with this wonderful breed.

Breed Standard for the Greyhound

Learn the requirements of a well-bred Greyhound by studying the description of the breed set forth in the American Kennel Club standard. Both show dogs and pets must possess key characteristics as outlined in the breed standard.

Your Puppy Greyhound

Be advised about choosing a reputable breeder and selecting a healthy, typical puppy. Understand the responsibilities of ownership, including home preparation, acclimatization, the vet and prevention of common puppy problems.

Everyday Care of Your Greyhound

Enter into a sensible discussion of dietary and feeding considerations, exercise, grooming, traveling and identification of your dog. This chapter discusses Greyhound care for all stages of development.

Training Your Greyhound

By Charlotte Schwartz

Be informed about the importance of training your Greyhound from the basics of housetraining and understanding the development of a young dog to executing obedience commands (sit, stay, down, etc.).

Health Care of Your Greyhound

Discover how to select a proper veterinarian and care for your dog at all stages of life. Topics include vaccination scheduling, skin problems, dealing with external and internal parasites and common medical and behavioral conditions.

Your Senior Greyhound

Consider the care of your senior Greyhound, including the proper diet for a senior. Recognize the signs of an aging dog, both behavioral and medical; implement a senior-care program with your veterinarian and become comfortable with making the final decisions and arrangements for your senior Greyhound.

Showing Your Greyhound

Acquaint yourself with the dog show world, including the basics of conformation showing and the making of a champion. Go beyond the conformation ring to different types of canine competition for the Greyhound.

Behavior of Your Greyhound

Learn to recognize and handle common behavioral problems in your Greyhound, including barking, separation anxiety, chewing, begging, aggression, etc.

KENNEL CLUB BOOKS®GREYHOUND

ISBN 13: 978-1-59378-237-5

Copyright © 1999 • Kennel Club Books® A Division of BowTie, Inc.40 Broad Street, Freehold, NJ 07728 USACover Design Patented: US 6,435,559 B2 • Printed in South Korea

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, scanner, microfilm, xerography or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright owner.

Photography by Carol Ann Johnson

with additional photographs by

Norvia Behling, T. J. Calhoun, Juliette Cunliffe, Doskocil, Isabelle Francais, Bill Jonas, Mikki Pet Products and Steve Sourifman.Illustrations by Renée Low

The publisher wishes to thank all of the owners whose dogs are illustrated in this book, including the La Grange-Beaume family.

Greyhounds dating back to the second century AD, depicted in a well-known carving housed in the British Museum.

Ancient silver coins bearing the Celtic Greyhound as ornamentation.

EARLY SIGHT HOUNDS

The Greyhound falls into the group of dogs classified as sight hounds, known also as gaze hounds, although in natural history the word “greyhound” is used to describe a whole group of similar dogs. A sight hound, of which the Greyhound is an early representative, is one that hunts its prey principally by sight. Its body is lean and powerful, with a deep chest and long limbs that provide both stamina and speed. Such hounds are adapted for finding prey in open country. Once the prey has been located, it can be overtaken by speed and endurance. Because of this special form of hunting, sight hounds historically have been found in regions where there is open countryside in North Africa, the Arabian countries, Afghanistan, Russia, Ireland and Scotland.

EARLY ANCESTORS

The Asiatic Wolf is most commonly accepted as the ancestor of the sight hounds, for no other wolves are known to have existed in areas where dogs of greyhound type originated. Large parts of the Sahara were once well watered, supplying plentiful herds of animals and providing excellent hunting grounds for these dogs. Dogs of the chase were looked upon quite differently from others, for Mohammed permitted these. The animals captured thus were allowed to be eaten, provided that the name of Allah was uttered when the dogs were slipped to give chase.

Celtic Greyhound, as shown on an ancient coin.

An ancient ring depicting a Celtic Greyhound killing a hare. The Celts were an ancient tribe originating in 1500 BC in Germany and spreading westward through France, Spain and Britain around 700 BC. They were conquered and absorbed by the Romans and barbarians; only Brittany and the west of the British Isles remained Celtic.

Thanks to the ancient Egyptians’ art of writing, we now have many pictures of early hounds, and even the names of many of them. Dogs were clearly venerated. Specific amounts of food had to be provided for them, and some were paid divine honors. Indeed, a war once broke out due to someone’s having eaten a dog from another city. In Egypt, the dog was mourned at death, with the Egyptian people sometimes fasting and shaving their heads. A dead dog was carefully embalmed, wrapped in linen and placed in a special tomb. Mourners wailed loudly and beat themselves as an expression of grief. Conversely, Hebrews loathed the dog and were taught not to fall into the error of worshiping it as a false idol.

Greyhound from a marble relief dating from the early second century AD. Note that the dog lacks the racy build of modern Greyhounds.

GREEKS AND THEIR GREYHOUNDS

Sight hounds were also known to the Greeks, and many such dogs were depicted in decorative metalwork. They were also portrayed in carvings of ivory and stone, and on terracotta oil bottles, wine coolers and vases. The Greyhound was one of three large dogs used by the Greeks, the others being the Mastiff and Molossian Hound. Interestingly, Socrates speaks of snares and nets being “everywhere prohibited,” from which one can deduce that it was considered unsporting to use such hunting methods.

Queen Elizabeth I, hawking with Greyhounds. From Turberville’s Book of Falconrie, 1611 edition.

The Greek historian Arrian lectured on coursing and, in AD 124, gave the following description of a Greyhound bitch: “I have myself bred a hound whose eyes are the greyest of grey. A swift, hard-working, courageous, sound-footed dog, and she proves a match at any time for four hares. She is, moreover, most gentle and kindly affectioned, and never before had I a dog with such a regard for myself.”

Arrian goes on to say that his bitch stayed close by his side when at home and followed him while outdoors. To remind him that she was to have her share of the food, she patted him with one foot and then the other. She also had many tones of “speech” to convey her wants. Clearly Arrian was a most considerate owner, for he also writes, “Nothing is so helpful as a soft, warm bed. It is best of all if they can sleep with a person, because it makes them more human, and because they rejoice in the company of human beings.”

Scene on a Greek amphora showing a Greyhound participating in “musical entertainment” of the time. From Athens, Greece, sixth century BC.

A Greyhound-and-hare lamp. This is of Greek origin from about the fourth century BC. The lip of the lamp is in the form of a hare, held in the Greyhound’s mouth

The Treatise on the Greyhound, written by Arrian, lay undiscovered in the library of the Vatican for many a long year, having been mistaken for a better known manuscript. Thankfully the treatise was eventually translated, and it was first published in English in 1831. In the treatise are many words of wisdom, among these comments about how to judge a fast, well-bred Greyhound. “First, let them stand long from head to stern…let them have light and well-knit heads…Let the neck be long, rounded and supple…Broad breasts are better than narrow, and let them have shoulder blades standing apart and not fastened together…loins that are broad, strong not fleshy, but solid with sinew…flanks pliant…Rounded and fine feet are the strongest.”

From Icones Animalium, 1780. The original caption reads Canis grajus.

GREYHOUNDS IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM

One of the most famous marble sculptures, housed in the British Museum, is of two seated Greyhounds, dating back to the second century AD. These hounds are remarkably similar to those we know today and, for those interested in the breed, a visit to the British Museum is well worthwhile.

EARLY GREYHOUNDS IN WALES

In southwestern Wales, in AD 500, two “white-breasted brindled greyhounds” ran beside Prince Kilburgh, the son of Kilhith, as he traveled to Arthur’s Court. These dogs wore broad collars, set with rubies, and they were said to have sprung about their owner like two sea-swallows.

FOREST LAWS

The Celts are clearly thought to have introduced the Greyhound to Britain from Asia, but specific dates are uncertain. Greyhounds, though, were specifically mentioned in the Forest Laws, which were made at Winchester by King Canute in 1016. A law was introduced that forbade commoners from owning Greyhounds, though freemen were allowed to keep them under certain conditions. If they lived within ten miles of the forest, the Greyhounds had to be cut at the knee so they could not hunt. Those living further away did not have to be cut, but, if they approached nearer to the forest, 12 pence was to be paid for every mile. Owners of Greyhounds found within the forest had to forfeit both the dog and ten shillings to the king.

The Greyhound Mick the Miller, a racer idolized by English racegoers during his career from 1928 to 1931. He is now preserved and on display at the British Museum.

Both the wolf and the wild boar were hunted with Greyhounds, so these dogs were both sufficiently large and powerful to cope with such prey. Before the signing of the Magna Carta (1215), there was proof that Greyhounds were held in extremely high esteem, for the destruction of such a hound was looked upon as an act “equaly criminal with the murder of a fellow man.”

Greyhounds were also frequently taken in payment as money for debts owed. In 1203, a fine paid to King John consisted of 500 marks, ten horses and ten leashes of Greyhounds. Seven years later, another debt was recorded as a swift running horse and six Greyhounds.

Master McGrath, another famous racing Greyhound whose career lasted from 1928 to 1931. He is preserved and displayed at the British Museum.

THE BOKE OF ST. ALBANS

No book about the Greyhound would be complete without the description of the breed given in The Boke of St. Albans, dated 1486. This was the first sporting book ever printed in English and, although some debate surrounds the authorship, the following verse (one of several slightly different versions) is attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, believed to have been prioress of Sopewell nunnery.

A greyhound should be headed like a Snake,

And necked like a Drake,

Footed like a Cat,

Tailed like a Rat,

Sided like a Team,

Chined like a Bream.

The first year he must learn to feed,

The second year to field him lead,

The third year he is fellow-like,

The fourth year there is none sike,

The fifth year he is good enough,

The sixth year he shall hold the plough,

The seventh year he will avail

Great bitches for to assail,

The eighth year lick ladle,

The ninth year cart saddle,

And when he is comen to that year

Have him to the tanner,

For the best hound that ever bitch had

At nine year he is full bad.

—Dame Juliana Berners

This is the first page of The Boke of St. Albans, 1486.

COURSING AND TRACK RACING

An important reason for combining the skills of dog and man was to hunt more effectively, one assisting the other. As a result, man began to breed dogs that were constructed in such a way that they could best bring down local game, hence providing an important part of the family’s diet.

The coursing breeds were developed to a large extent in the Middle East, and coursing contained a competitive element even as early as 4000 BC. This eventually led to codes of practice, something we learn of in Arrian’s writings in the second century AD.

Greyhounds, like many other sight-hound breeds, have remained true to type over the centuries. It is because of this that many have continued to carry out the work for which they were originally bred and adapted.

Coursing at Swaffham from The Sporting Magazine, 1793.

A detail from a 1436 painting by Pisanello called “Vision of St. Eustace.”

In Great Britain, coursing was not conducted under established rules until the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Responsible for drawing up the rules, the Duke of Norfolk stipulated that a hare was never to be coursed with more than a brace of Greyhounds, nor was she to be killed while “on her seat.” It was also decreed that the quarry was to be given 12 score yards before the hounds were loosed so that the dogs would not leap on her as soon as she rose. Much was written about the sport in the 17th century, and Greyhounds featured prominently.

FAMOUS FANCIERS

Many famous people throughout history have owned Greyhounds. According to legend, Cleopatra had coursing Greyhounds, and Greyhounds are always depicted as the hunting hounds of the goddess Diana. Other prominent owners have included Frederick the Great and Prince Albert, of whom the lovely Greyhound Eos was a particular favorite.

For part of her life, Queen Elizabeth I did not hunt personally, but she witnessed the coursing of deer by Greyhounds from her residence. She is recorded as having witnessed “from a turret at Cowdrey Park sixteen bucks, all having fair law, pulled down by Greyhounds upon the lawn one day after dinner.” Indeed, dogs have long played a part in the history of Britain through its rulers, for London’s Isle of Dogs actually derived its name from being the place where Edward III (1327–1377) kept his Greyhounds and spaniels.

Lord Orford’s Czarina and Maria from Rural Sports, 1801

HOUNDS AROUND THE WORLD

While the United Kingdom lays claim to the world’s most famous sight hounds, namely the Greyhound, Whippet, Deerhound and Irish Wolfhound, other nations and regions have produced impressive greyhound types. Afghanistan’s namesake, the Afghan Hound, Italy’s Italian Greyhound and Cirneco dell’Etna, Malta’s Pharaoh Hound, Spain’s Ibizan Hound and Galgo Español, Iran’s Saluki, Morocco’s Sloughi and Zimbabwe’s Rhodesian Ridgeback are counted among other recognized sighthound breeds. Further, lesser known dogs from Russia, such as the Tazy, Taigan and Chortaj, Hungary’s Magyar Agar, Mali’s Azawakh and Poland’s Chart Polski also represent this classic greyhound type around the world.

LORD ORFORD’S INFLUENCE ON THE BREED

During the 18th century, Lord Orford, seemingly not content with this already splendid breed, set about developing a faster Greyhound. He introduced several experimental crosses, including the Bulldog in an endeavor to increase persistence. The reason for this was that he had been impressed by the determination displayed by Bulldogs when fighting in the pit. Apart from the Bulldog, the Deerhound, Lurcher and Italian Greyhound also were introduced into the Greyhound breed.

KANGAROO HOUND

Australia once boasted its own Greyhound breed known as the Kangaroo Hound, developed to hunt wallabies, dingoes and, of course, kangaroos. These dogs, heavier than a typical Greyhound, never gained the favor of the breeders and subsequently became extinct as the protection of the native Australian wildlife made the national agenda.

Fullerton was sold as a puppy for a then-record sum of 850 guineas. His body now rests in Britain’s Natural History Museum. The illustration is from The Dogby Wesley Mills, 1892.

Initially Orford’s theories were considered absurd, but soon dogs produced as a result of his breeding program were considered both the fastest and sturdiest, and hence the most efficient, running dogs. At times he was known to have kept 50 braces of Greyhounds, and it was a rule never to part with a single whelp until it had a fair and substantial trial of speed.

Upon the death of Lord Orford, the best dogs of his strain were purchased by Colonel Thornton and thus moved northward to Norfolk and Yorkshire. However, except when they were working on flat country, their success apparently fell below expectations.

Greyhound with hare from the Naturalists Library, 1840.

With foundations laid down by Lord Orford, the first coursing club was established at Swaffham in 1776 with members confined in number to the letters of the alphabet. There was no letter “I,” so membership stood at 25. Subscriptions were moderate, but there were monetary fines for non-attendance at meetings and for breaking the rules. The National Coursing Club, with its own stud book, was commenced in 1858.

“I AND McGRATH”

One of the most famous winners of the Greyhound world’s Waterloo Cup had an audience with that great dog lover, Queen Victoria. The dog, Master McGrath, traveled to meet her by private train.

The coursing Greyhound, however, is generally smaller than the Greyhound found in today’s show ring, and most winners of the famous Waterloo Cup have been comparatively small. Although there used to be “park coursing,” in which hares were released for the purpose, this is not now so; such release has not been permitted in England for around 100 years. In 1976, the House of Lords Select Committee found that no unnecessary suffering was caused to the hare by coursing.

Numbers of coursing Greyhounds registered far outnumber those registered with the English Kennel Club for the purposes of showing. Although from the 20th century, many consider Cornwall to be the original home of the show Greyhound, few were exhibited in the south of England towards the close of the 19th century. There was better participation in the classes of shows held in northern England.

The Greyhound Lauderdale from the Illustrated Book of the Dog, 1881.

Track racing developed from coursing, partly as a means of controlling the crowds of onlookers at coursing meetings. An artificial lure was developed and first used in England in 1876. This was a stuffed rabbit that ran on a long rail, but it did not prove popular. Enclosed coursing in parks was much more in favor. Not until the early 20th century did track racing became popular, following the development of a lure that could be run around a track. The first racing stadium was created in Manchester in 1926.

Many well-known racing Greyhounds will go down in the annals of history, among them Fullerton, who was sold to his owner Colonel North for a record price of 850 guineas. Fullerton won 31 of his 33 races, including the Waterloo Cup in 1889, 1890 and 1891, and sharing the honors in 1892.

AN ALLURING NOTION

In Australia, mechanical lure racing was pioneered by Frederick Swindell, an American who had moved to the country in 1927. As a result, the Greyhound Coursing Association was established that same year. A mechanical lure circuit was permitted on the site now known as Harold Park.

Greyhound named Age of Gold, bred and owned by F. Alexander, Esq. From the painting by Lilian Cheviot in the New Book of the Dog by Robert Leigh, 1907.

Mick the Miller was another Greyhound idolized by millions of racegoers in Britain in the 1920s and ‘30s. The bodies of both of these great hounds are preserved in the British Museum.

THE NAME “GREYHOUND”

There is much conjecture about the origin of the name “Greyhound.” It has been spelled variously as “grehounde,” “griehounde,” “grayhounde,” “graihound,” “grewhound” and “grewnd.” One early authority considered that it was drawn from the ancient English word grech or greg, meaning “dog.” This may be so, but others believe that it relates to the color of the breed in its early days. However, there is no evidence to suggest that grey (spelled also as “gray,” “grai” and “grei”) was the prevailing color, the breed also being found in sandy red, brindle, pale yellow and white.

Another theory is that the name implies “Gallic hound,” giving rise to the conjecture that it actually originated in Gaul. Followers of this theory consider that the word can be translated as gradus in Latin, meaning “degree,” because it exceeded the speed of other dogs. “Gree” was certainly used to represent the word “degree.” A further theory worthy of consideration is that the word grew was often used for “Greek,” thus indicating a connection with Greece.

GREYHOUNDS IN THE AMERICAS

The Greyhound arrived in the Americas with the Spanish in the 16th century, as well as with early British colonists. These dogs were used on America’s Great Plains, useful for protecting crops from devastation by rabbits, and livestock from danger from coyotes. Although they hunted a variety of game, they were most highly renowned for their excellence in chasing hare and rabbit.

In 1885, the Greyhound was one of the first six hound breeds to be registered with the American Kennel Club (AKC), but this was the only breed to represent the sight hounds.

THE FIRST CRUFTS BEST

The year 1928 was the first year in which Crufts made an official Best in Show award open to any entrant. Hitherto there had been a prize for Best Champion, but not Best in Show. The first winner of this important award was a Greyhound, Primely Sceptre, and this title was won again by Greyhounds in 1934 and 1956.

Formed in 1907, the Greyhound Club of America (GCA) became the breed’s national parent club, being recognized by the AKC two years later. The breed had been exhibited for over 25 years by this point, including an entry of 16 dogs in the 1880 Westminster Kennel Club show in New York City. The GCA’s first national specialty took place in October of 1923 on grounds owned by fancier J. S. Shipps of Long Island. Both conformation and coursing were included in this first event. With the exception of a few years, the specialty on the East Coast has occurred annually and attracted fair numbers of American fanciers. A West Coast specialty began in 1968, set into motion by the breed’s growing popularity on that shore.

The popular actress Annette Crosbie (left) befriends a Greyhound rescue dog at Britain’s Crufts Dog Show.

CUSTER’S LAST STAG?

General George A. Custer traveled with a pack of 40 Greyhounds and Staghounds. The day before departing for his fatal expedition to Big Horn River in 1876, his dogs were to run a matched race.

Since the 1920s, the Greyhound in America has been involved with track racing, but the breed still also is kept both as a sporting hound and as a companion. Clearly the Greyhound is synonymous with speed, and even the famous Greyhound buses carry the breed’s name, presumably to convey the efficiency, speed and endurance of their renowned service.

A racing Greyhound in action. The dog’s front legs are taped for support.

SHOW GREYHOUNDS IN EUROPE

With the Greyhound’s being such an endearing and well-mannered breed, it is perhaps surprising that they are not represented in stronger numbers on the show bench. At a recent International Championship Show in Holland, there were only 15 Greyhounds entered, compared to 48 Whippets and 46 Afghan Hounds.

In Britain, at a recent Crufts show, there were 73 Greyhounds entered, a significantly higher number than at most shows on the Continent. However, this is still far fewer than the other well-known sight hound breeds, with Whippets topping 300 for the sake of comparison.

You have to be fairly tall to have your Greyhound stretch for a treat.

Few Greyhounds are shown at major dog shows. They are, however, becoming more and more common as pets, as an increasing number of people opt to make retired racers part of their lives.