Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Comprehensive Owner's Guide

- Sprache: Englisch

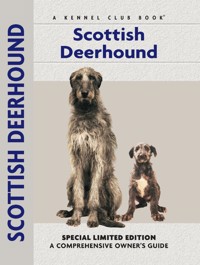

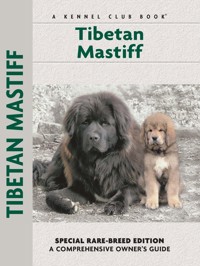

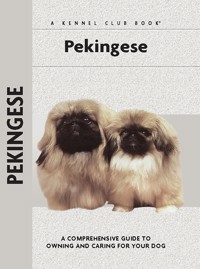

The experts at Kennel Club Books present the world's largest series of breed-specific canine care books. Each critically acclaimed Comprehensive Owner's Guide covers everything from breed standards to behavior, from training to health and nutrition. With nearly 200 titles in print, this series is sure to please the fancier of even the rarest breed.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 213

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Physical Characteristics of the Pekingese

(from the American Kennel Club breed standard)

Neck: Very short, thick and set back into the shoulder.

Skull: Topskull is massive, broad and flat.

Ears: Heart-shaped and set on the front corners of the skull extending the line of the topskull.

Eyes: Large, very dark, round, lustrous and set wide apart.

Nose: Black, broad, very short and in profile, contributes to the flat appearance of the face. Nostrils are open.

Pigment: Skin of the nose, lips and eye rims is black on all colors.

Wrinkle: Effectively separates the upper and lower areas of the face. The appearance is of a hair-covered fold of skin, extending from one cheek, over the bridge of the nose in a wide inverted “V,” to the other cheek.

Stop: Deep.

Muzzle: Very short and broad with high, wide cheek bones.

Mouth: Lower jaw is slightly undershot. The lips meet on a level plane and neither teeth nor tongue show when the mouth is closed.

Forequarters: Short, thick and heavy-boned. The bones of the forelegs are slightly bowed between the pastern and elbow. Shoulders are gently laid back and fit smoothly into the body. The elbows are always close to the body. Front feet are large, flat and turned slightly out.

Proportion: Length of the body, from the front of the breast bone in a straight line to the buttocks, is slightly greater than the height at the withers. Overall balance is of utmost importance.

Body: Pear-shaped and compact. It is heavy in front with well-sprung ribs slung between the forelegs. The broad chest, with little or no protruding breast bone, tapers to lighter loins with a distinct waist. The topline is level.

Tail: Base is set high; the remainder is carried well over the center of the back. Long, profuse straight feathering may fall to either side.

Hindquarters: Lighter in bone than the forequarters. There is moderate angulation and definition of stifle and hock. When viewed from behind, the rear legs are reasonably close and parallel and the feet point straight ahead.

Coat: Body Coat: Full-bodied, with long, coarse textured, straight, stand-off coat and thick, softer undercoat. The coat forms a noticeable mane on the neck and shoulder area. Feathering: Long feathering is found on the back of the thighs and forelegs, and on the ears, tail and toes.

Color: All coat colors and markings, including parti-colors, are allowable and of equal merit.

Size/Substance: Stocky, muscular body. All weights are correct within the limit of 14 pounds, provided that type and points are not sacrificed.

Contents

History of the Pekingese

Revered for its size, personality, intelligence and looks, the Pekingese is one of today’s most popular dogs. Discover its imperial beginnings in China, learn about important people in the breed’s early days and trace its journey into the Western World.

Characteristics of the Pekingese

The Pekingese is as distinct in personality as he is in looks. Find out all about the breed’s temperament, what physical characteristics make him unique and the best kind of owner for a Pekingese, as well as breed-specific health concerns.

Breed Standard for the Pekingese

Learn the requirements of a well-bred Pekingese by studying the description of the breed set forth in the American Kennel Club standard. Both show dogs and pets must possess key characteristics as outlined in the breed standard.

Your Puppy Pekingese

Be advised about choosing a reputable breeder and selecting a healthy, typical puppy. Understand the responsibilities of ownership, including home preparation, acclimatization, the vet and prevention of common puppy problems.

Everyday Care of Your Pekingese

Enter into a sensible discussion of dietary and feeding considerations, exercise, grooming, traveling and identification of your dog. This chapter discusses Pekingese care for all stages of development.

Training Your Pekingese

By Charlotte Schwartz

Be informed about the importance of training your Pekingese from the basics of house-breaking and understanding the development of a young dog to executing obedience commands (sit, stay, down, etc.).

Health Care of Your Pekingese

Discover how to select a qualified vet and care for your dog at all stages of life. Topics include vaccinations, skin problems, dealing with external and internal parasites and common medical and behavioral conditions, plus a special section on eye disease.

Showing Your Pekingese

Experience the dog show world in the conformation ring and beyond. Learn about the American Kennel Club, the different types of shows and the making of a champion, as well as obedience and agility trials.

KENNEL CLUB BOOKS®PEKINGESE

ISBN 13: 978-1-59378-253-5

eISBN 13: 978-1-93704-976-8

Copyright © 2003 • Kennel Club Books®A Division of BowTie, Inc.

40 Broad Street, Freehold, NJ 07728 USA

Cover Design Patented: US 6,435,559 B2 • Printed in South Korea

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, scanner, microfilm, xerography or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright owner.

Photographs by Carol Ann Johnson, with additional photographs by:

Norvia Behling, T. J. Calhoun, Doskocil, Isabelle Français, Bill Jonas, Mikki Pet Products and Alice Roche.

Illustrations by Renée Low.

The publisher would like to thank the owners of the dogs featured in the book, including Maria Castro, Anthony & Elizabeth Deck, Gloria Henes, Edith N. Jones, Roxanne Luchesi, Miss Winnie Mee, Lorraine Moran, Nicolas Odette, Sylvia Roznick, Alice & Robert Sohl, Ev Spaulding, Susan Speranza and Elizabeth Tilley.

Eng. Ch. Chu-Erh of Alderbourne, owned by Mrs. C. Ashton Cross and painted by Lilian Cheviot in 1907.

The Pekingese boasts an enormously rich history and is deservedly a breed that enjoys great popularity throughout the world. Bred meticulously by sovereigns of Imperial China for centuries, the Pekingese was a special favorite in the royal palaces, where he was kept separately from the other castle dogs.

Those kept in the palaces were of finer quality than the Pekingese kept by the commoners, the latter being somewhat larger and coarser in general appearance. Dogs of the royal households were occasionally presented to other Eastern monarchs and doubtless some of their bloodlines filtered through to other breeds of the East. The Japanese Chin, Pug, Tibetan Spaniel and the charming Happa Dog, meaning “under-the-table” dog, who looked rather like a short-coated Peke, are some obvious examples. Although breeds such as these are still distantly related, their relationship in the Middle Ages was much closer than it is today.

It is believed that in early times, the Pekingese was owned only by the highest court dignitaries, those of royal blood. Just as commoners were forbidden to look at the Emperor, so were they obliged to turn away their heads, upon pain of death, whenever the Pekingese appeared. Certainly this little dog was held in the greatest esteem; some say it was almost sacred. There were even Pekingese that had high literary awards bestowed upon them. One was given the official Order of the Hat, which might be compared to today’s Nobel Peace Prize!

THE PEKINGESE IN ART

From Chinese art, we can see clearly that the Pekingese and the Pug were two quite separate breeds; this was evident in the Imperial Chinese brushwork. Thousands of years before the Christian era, dogs appeared on Chinese bronzes, and later there were small lion-like dogs found on pottery and porcelain. In Chinese Buddhist art, a sacred mythological lion was much used in symbolic form and eventually the Pekingese dog itself was allowed to represent this symbol.

Paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries give us a fairly clear insight into dogs bred in the Imperial Palace, for court artists were often commissioned to paint dogs housed in the Palace. There was one particular scroll of note, tenderly portraying 100 dogs, painted by Tsou Yi-Kwei.

In art of the 18th century, the Pekingese generally conformed to a rather conventional pattern. The dog was always uniform in its markings and always had a similar expression, with large goggle-eyes. Even as late as the end of the 19th century, the Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi, famed for her love of the Pekingese, followed this style in her own paintings, as did her painting instructress.

The famous Pekingese breeder, Mrs. Vlasto, and two of her famous champions: See Mee of Remenham, born in 1922, on the left and Remenham Dimple, born in 1923, on the right.

Indeed there are many valuable works of Chinese art, rich in their portrayal of the “Lion Dog,” as the Pekingese was called. Many of these are housed in museums open to the public, but there are many others in private collections. During the 19th century, the paintings more closely resembled living dogs, and these could be found as beautifully painted miniatures, on fans, snuff bottles, lanterns, screens and caskets.

THE EMPRESS TZU HSI

As a Princess in Peking, Tzu Hsi was inordinately fond of all small animals and singing birds, always finding time to attend to her animal friends. In later life, she was affectionately known as “Old Buddha” and she continued her interest in breeding dogs to the end of her days as Empress.

Before Tzu Hsi’s time, small dogs customarily had their growth stunted with mechanical devices and drugs. This enabled them to be carried in ladies’ sleeves in court, giving rise to the name “Sleeve Dog.” The Empress, however, restricted these methods and encouraged natural methods, including selective breeding as a means of keeping size down.

The majority of her Pekingese was sable or rich red in color, but she liked many colors and certainly also had black, parti-colored and white ones. It was even said that some of her dogs were bred to match the color of the peonies and the fruit that grew along the shores of the lakes on the grounds of the Summer Palace.

Although the quotation is lengthy, no book about the Pekingese would be complete, in the author’s opinion, without including an interpretation of Empress Tzu Hsi’s description of and advice about the Pekingese. These words were delicately described as “pearls dropped from the lips of Her Imperial Majesty Tzu Hsi, Dowager Empress of the Flowery Land of Confucius:”

Let the Lion Dog be small;

Let it wear the swelling cape of dignity around its neck;

In Chinese folklore and art, the Pekingese is highly regarded, admired for his nobility, beauty, symmetry and wisdom.

Let it display the billowing standard of pomp above its back;

Eng. Ch. Portelet Tzu Ting, bred by Mrs. Barber in 1919, was a big-time winner in the UK, placing in nine Championship Shows in 1922 alone.

Let its face be black;

Let its forefront be shaggy;

Let its forehead be straight and low,

Like unto the brow of an Imperial harmony boxer.

Let its eyes be large and luminous; Let its ears be set like the sails of a war junk;

Let its nose be like that of the Monkey God of the Hindus.

Let its forelegs be bent,

So that it shall not desire to wander far,

Or leave the Imperial Precincts.

Let its body be shaped

Like that of a hunting lion spying for its prey.

Let its feet be tufted

With plentiful hair that its footfall may be soundless;

And for its standard of pomp,

Let it rival the whisk of the Tibetan yak,

Which is flourished to protect the Imperial litter

From the attacks of flying insects.

Let it be lively,

That it may afford entertainment by its gambols;

EARLY COLORS

Most Pekingese bred during the breed’s first 60 years in the West were red with dark masks, but there were also fawns, blacks, black-and-tans and a few whites, though these often turned cream in adulthood. The first pure white strain was established in the 1920s. Liver color with chocolate points was also known.

Let it be discreet,

That it may not involve itself in danger;

Let it be friendly in its habits,

That it may live in amity with other beasts,

Fishes or birds that find protection in the Imperial Palace.

And for its color

Let it be that of a lion—a golden sable,

To be carried in the sleeve of a yellow robe,

Or the color of a red bear,

Or of a black bear, or a white bear, or striped like a dragon

So that there may be dogs Appropriate to each of the Imperial robes.

Let it venerate its ancestors,

And deposit offerings in the dog cemetery

Of the Forbidden City on each New moon.

Let it comport itself with dignity

Let it learn to bite the foreign devils instantly.

Let it be dainty in its food

That it shall be known as an Imperial dog

By its fastidiousness.

Sharks’ fins

And curlews’ livers

And the breasts of quails, on these may it be fed;

And for drink

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Pekingese has been misspelled as “Pekinese” in the past, and this caused a lot of discussion among breeders in the 1950s. Other names have also been used, such as Peking Dog and Peiching kou, which both have the same meaning, and Dragon Dog, Lion Dog, Peking Palace Dog and Sleeve Dog.

Give it the tea that is brewed from the spring buds

Of the shrub that grows in the province of Hankow,

Or the milk of the antelopes That pasture in the Imperial Parks.

Thus shall it preserve its integrity and self-respect

And for the day of sickness let it be anointed

With the clarified fat of the leg of a sacred leopard,

And give it to drink a throstle’s eggshell full of the juice

Of a custard apple in which has been dissolved three pinches

Of shredded rhinoceros horn, and apply to it piebald leeches

So shall it remain–but if it die, Remember, that thou too art mortal!

The Empress was extremely conscientious and methodical, both in her work and in her play, and though at times she could be flexible, at others she could be quite ruthless. She undoubtedly became one of the greatest Empresses of the East and was compared in her way to Queen Victoria. The Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi died in November 1908. The following year, her remains were buried, with a funeral costing half as much as any previous royal funeral. A favorite Pekingese was carried to precede the Imperial bier to the tombs. This was Moon-tan, meaning “peony,” who had a yellow and white spot on the forehead. The event was reminiscent of the death of Emperor T’ai Tsung some 900 years earlier. His dog, Tao Hua, meaning “peach flower,” followed his master to his last resting place, and there died of grief, it is said, at the portal of the Imperial tomb.

It was said that the Empress’s dog also died of grief, but others believe Moon-tan was smuggled away and sold by one of the eunuchs.

Sun Chi of Greystones with His Highness Pratap Singh, Maharajah of Nabha in the 1930s.

THE ARROW WAR

A war, known as the Arrow War, was waged between China and the Western Allies in the 1860s. The Imperial household was evacuated from Peking shortly before the invaders arrived in the Forbidden City. However, five Pekingese dogs were left behind at the Summer Palace. These were believed to have belonged to an aunt of the Emperor, who had chosen not to flee, but instead to stay behind and commit suicide. British officers seized these dogs and took them to Britain, these being the first known Pekingese to have arrived on these shores. One of these five was exceptionally small and was carried around in the forage cap of Lt. Dunne. She was renamed “Looty” and was presented to Queen Victoria, in whose care she remained until her death in 1872.

Eng. Ch. Ko Tzu of Burderop, born in 1910, bred and owned by Mrs. E. Calley, won 20 Challenge Certificates before World War I temporarily ended dog showing in Europe.

Looty was fawn and white in color and weighed but 3 lb. She was not heavily feathered and rather more resembled a Lo-sze, which was a kind of smooth-haired Pekingese. It seems likely that Looty lived at Windsor Castle, but she probably spent most of her days in the kennels there, rather than as one of the pets in the castle. A painting of her was made in 1863, this by a pupil of the renowned artist Sir Edwin Landseer.

The other four Pekingese were brought to Britain by Lord John Hay and Sir George Fitzroy. The two brought by the former were a black and white dog, Schlorf, and a bitch, Hytien, who weighed a little over 4.5 lb and was a rich chestnut color with a dark mask. Lord Hay gave these to his sister, the Duchess of Wellington, and with the aid of the dog, who lived to the ripe old age of 18, she was able to keep the breed going at Strathfieldsaye. The other two were both fairly small, dark chestnut in color, with dark masks. It was from these two that the famous Goodwood strain was produced.

There are various accounts of the ransacking of the Summer Palace, which took place in the latter part of 1860. One account tells readers that six Pekingese were thrown down a well, instead of being left for the “foreign devils.” Indeed, wells were used for many things besides water, including disposal of the Emperor’s chief concubine! It is highly likely that more dogs were smuggled outside the Palace, and that these were sold by the eunuchs to high-ranking Chinese nobles. Certainly a few dogs were later found beyond the palace walls, and these were thought to closely resemble the exquisite dogs of the Palace.

ESTABLISHMENT IN BRITAIN

As we have seen, breeding of the Pekingese took place at Strathfieldsaye and at Goodwood, and by the late 1890s there were at least 17 Pekes at Fulmar Palace in Slough, with Lord John Hay. He called these dogs Peking Spaniels and wrote most interesting accounts of their antics. They even sailed across the lake on little rafts and performed wonderful gymnastic feats!

The famous British show dog, Eng. Ch. Tai Yang of Newnham, bred and owned by Mr. Herbert Cowell, won 40 Challenge Certificates in the 1930s. This was a record for any breed during those times.

The Goodwood Kennels were already famous, for they had been built in 1787 to house the Good-wood Pack of Foxhounds. By the late 19th century, it seems likely that the Pekingese were kept as pets in Goodwood House, where other small breeds had been looked after. Goodwood’s Duchess of Richmond gave some Pekingese to intimate friends. At this time, appropriately enough, many of the breed’s main supporters were members of the aristocracy.

From the end of the Arrow War, through the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 and until the death of the Empress Tzu Hsi in 1908, many westerners had connections with China. Consequently, dogs of genuine Pekingese type, and some less so, were brought to Britain during this time. Most of these early importers were army officers.

Going back to 1860, when the five Pekingese dogs were found in the Summer Palace, there were reports that another 14 “odd-looking little dogs” were found upon bursting open a locked door. Two of these dogs came to England in 1863. Lara and Zin, the latter a pure white Pekingese, were presented as a wedding gift to Lord and Lady Hay. Zin suffered an accident and was replaced by another dog, named Foo. It is probable that the first two of these were Chinese-bred.

It is all too easy to become bogged down in the fascinating events of those early decades of the breed’s history in the West. In 1885, a brace was sent to Britain from China by Admiral Sir William Dowell. There also was a dog given by a Palace eunuch in exchange for medical services rendered. This dog is counted among several influential early stud dogs of repute and commanded stud fees of five or ten guineas, a considerable sum in those days.

Madam of Winwood and Little Joke of Winwood represent the breed in the 1930s.

PEKINGESE CLUB

In 1898, it was the Japanese Spaniel Club that drafted a breed standard for the Pekingese, but in 1900 the club’s name was changed to Japanese and Asiatic Spaniel Association. From this developed the Pekingese Club, in 1902, followed soon after by the Peking Palace Dog Association.

PRESERVED FOR POSTERITY

Several early Pekingese are in Britain’s Natural History Museum, preserved for posterity’s sake. Among them are Ah Cum, a red dog imported from China in 1896 and one of his grandchildren, Palace Yo Tei, winner of eight first prizes at Crufts. She died in 1908, at under four years of age.

The breed was becoming highly popular and strengthening in numbers. England’s national breed club was formed in 1904, and of course the Pekingese was assisted by some influential breeders. Mrs. Clarice Ashton Cross started her highly influential Alderbourne Kennel after World War I, and there were many breeders of merit between World Wars I and II.

THE PEKINGESE ARRIVES IN THE US

It was not until after the Boxer Rebellion that the Pekingese appeared in the USA. The Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi made gifts of dogs to several influential American society women; among them was Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter, Alice, who was given a black dog.

Occasional specimens were smuggled out of Peking, but this was hazardous, and eunuchs caught involved in such acts were liable to suffer death by torture. The first of the breed to be shown in the US was a dog called “Pekin;” this was in 1901. However, Americans interested in breeding Pekingese tended to look toward Britain for their imports.

According to the American Kennel Club (AKC), it first registered the Pekingese in 1906. Just a couple of years prior, T’sang of Downshire had appeared in the show ring at Cedarhurst, Long Island. He was owned by Mrs.Morris Mandy, who had come from Britain to live in the United States. T’sang of Downshire was the first of the breed to complete his championship, and, in 1908, the first Pekingese bitch to gain a Champion of Record title was Chaou-Ching-Ur, bred by the Dowager Empress and owned by Dr. Mary Cotton. It was sad that Chaou-Ching-Ur, who was black, left no offspring, but it is believed that the first official British and American breed standards were based on her.

Queen Alexandra with one of her favorite Pekingese, from a famed painting by Sir Luke Fildes, on display at the UK’s National Portrait Gallery in London.

Mrs. F. M. Weaver, in 1912, with her famous Sutherland Ouen Teu Teng, was credited with keeping the breed true to the old type.

Eng. Ch. Tien Joss of Greystones, photographed in 1915, was a valuable sire during that period.

From the time that the Pekingese became officially recognized in America, it grew in popularity, with fanciers getting together to help advance the breed. This resulted in the formation of the Pekingese Club of America (PCA) in 1909, with Mrs. Mandy and Dr. Cotton as two of its founding members. Mrs. Mandy became the club’s first acting president. The club’s main sponsor was Mr. J. P. Morgan, who also served as honorary president and was an extremely well-known fancier of the breed in its early years in the US.

The breed standard of England’s Pekingese Club had been drawn up some five years prior to the American standard, and the PCA decided to adopt the first version of its own standard from the former. In this way, the parent clubs of Britain and the United States similarly outlined ideal breed characteristics, initially implementing a weight limit of 18 lb (8.2 kg). This was out of line with the average weight of original Chinese imports to both countries, these having weighed between 3 and 9 lb (1.4-4.1 kg). Later, the American club altered the weight clause and made any weight over 14 lb (6.4 kg) a disqualification. This indeed has been the only disqualification in the AKC standard, and remains so up to the present day.

Today, there are many AKC-licensed Pekingese clubs across the vast expanse of the US, so it is sadly impossible to pay tribute to all of them individually. Clubs bring enthusiasts together, to work for the betterment of the breed. In America, there are Pekingese clubs doing an enormous amount of good work, particularly for rescued Pekes, which is highly commendable.

Founded in the northeastern US, the Pekingese Club of America is one of the oldest clubs in the country and held an independent winter specialty show in New York City as far back as 1911. This was an inaugural event held in the fashionable ballroom of the Plaza Hotel, and attracting 94 dogs. Indeed the club has a stunning history and has historically presented a large selection of solid silver trophies to its winners. Most distinguished of these trophies is the Lasca McLuyre Halley perpetual trophy, the largest ever offered at a dog show. This, and the J.P. Morgan Trophy, can be seen on permanent display in the Library of the American Kennel Club in New York. Just once a year they are removed from their display case for presentation and cherished photographs with the Best of Breed and Best Opposite Sex winners at the PCA’s winter specialty. This is now held in conjunction with the Empire Specialties Associated Clubs Inc., just prior to the Westminster Kennel Club show.

Eng. Ch. Meng of Alderbourne, bred by Mr. B. Boxley in 1928, was exported to India, where it was used in the development of the breed in that country.

An ancestral asset was Ta Fo of Greystones, bred by Miss Heuston in 1910.