Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

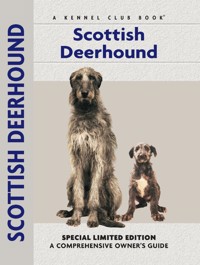

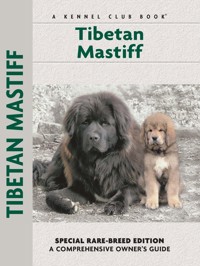

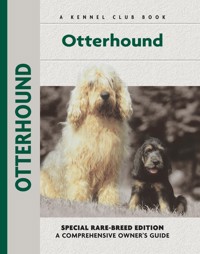

- Serie: Comprehensive Owner's Guide

- Sprache: Englisch

Noble and dignified, if somewhat tousled, the Otterhound is no longer called upon to hunt his namesake quarry, though he now makes a reliable companion dog for an active family who knows how to keep him busy. This giant hunting scenthound is blessed with a boisterous nature, a sonorous voice and an irrepressible love of mud, traits that may not be welcome in every household. No dog as big (and messy) as the Otterhound is for everyone, and the Otterhound—though personable, even-tempered and friendly—is no exception. Author Juliette Cunliffe, a recognized authority on hound breeds the world over, paints a pleasing but realistic portrait of this majestic hound among hounds, offering sensible information about the breed's training, feeding, care and maintenance. Students of the Otterhound will welcome the author's concise but complete history of the breed in England as well as American breeder Elizabeth Conway's retelling of the breed's history in the United States. Like all editions in Kennel Club Books' Comprehensive Owner's Guide series, Otterhound discusses the breed standard, breed characteristics, puppy selection, owner requirements, healthcare and much more. Surely all admirers of this noble breed will welcome this Special Rare-Breed Edition as a cherished addition to their canine libraries.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 252

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Physical Characteristics of the Otterhound

(from the American Kennel Club breed standard)

Head: The head is large, fairly narrow, and well covered with hair. The head should measure 11 to 12 inches from tip of nose to occiput in a hound 26 inches at the withers, with the muzzle and skull approximately equal in length. The skull (cranium) is long, fairly narrow under the hair, and only slightly domed.

Eyes: Deeply set. The haw shows only slightly. The eyes are dark, but eye color and eye rim pigment will complement the color of the hound.

Muzzle: Square. The jaws are powerful with deep flews. From the side, the planes of the muzzle and skull should be parallel.

Nose: Large, dark, and completely pigmented, with wide nostrils.

Jaws: Powerful and capable of a crushing grip. A scissors bite is preferred.

Chest: Deep reaching at least to the elbows on a mature hound. Forechest is evident, there is sufficient width to impart strength and endurance. The well sprung, oval rib cage extends well towards the rear of the body.

Forequarters: Shoulders are clean, powerful, and well sloped with moderate angulation at shoulders and elbows. Legs are strongly boned and straight, with strong, slightly sprung pasterns. Dewclaws on the forelegs may be removed.

Feet: Both front and rear feet are large, broad, compact when standing, but capable of spreading. They have thick, deep pads, with arched toes; they are web-footed (membranes connecting the toes allow the foot to spread).

Ears: Long, pendulous, and folded (the leading edge folds or rolls to give a draped appearance). They are set low, at or below eye level, and hang close to the head, with the leather reaching at least to the tip of the nose. They are well covered with hair.

Neck: is powerful and blends smoothly into well laid back, clean shoulders, and should be of sufficient length to allow the dog to follow a trail. It has an abundance of hair; a slight dewlap is permissible.

Topline: Is level from the withers to the base of tail.

Tail: Set high, and is long reaching at least to the hock. The tail is thicker at the base, tapers to a point, and is feathered (covered and fringed with hair). It is carried saber fashion (not forward over the back) when the dog is moving or alert, but may droop when the dog is at rest.

Hindquarters: Thighs and second thighs are large, broad, and well muscled. Legs have moderately bent stifles with well-defined hocks. Hocks are well let down, turning neither in nor out. Angulation front and rear must be balanced and adequate to give forward reach and rear drive. Dewclaws, if any, on the hind legs are generally removed.

Size: Males are approximately 27 inches at the withers, and weigh approximately 115 lbs. Bitches are approximately 24 inches at the withers, and weigh approximately 80 lbs.

Coat: The outer coat is dense, rough, coarse and crisp, of broken appearance. Softer hair on the head and lower legs is natural. The outer coat is two to four inches long on the back and shorter on the extremities.

Color: Any color or combination of colors is acceptable.

Contents

History of the Otterhound

With the influence of British and French hounds in its makeup, the Otterhound was developed for exactly what its name implies—hunting otter! Learn about the sport and significant hunting packs, as well as the breed’s eventual transition to pet and show dog once otter hunting was banned in the UK.

Characteristics of the Otterhound

Meet the big, boisterous and baying Otterhound! A personable hound with an expression that bespeaks his friendly nature, the Otterhound is best for active owners who don’t mind muddy paws. Discuss temperament, physical characteristics and health concerns to find out if this is the breed for you.

Breed Standard for the Otterhound

Learn the requirements of a well-bred Otterhound by studying the description of the breed set forth in the American Kennel Club standard. Both show dogs and pets must possess key characteristics as outlined in the breed standard.

Your Puppy Otterhound

Find out about how to locate a well-bred Otterhound puppy. Discover which questions to ask the breeder and what to expect when visiting the litter. Prepare for your puppy-accessory shopping spree. Also discussed are home safety, the first trip to the vet, socialization and solving basic puppy problems.

Proper Care of Your Otterhound

Cover the specifics of taking care of your Otterhound every day: feeding for the puppy, adult and senior dog; grooming, including coat care, ears, eyes, nails and bathing; and exercise needs for your dog. Also discussed are the essentials of dog identification.

Training Your Otterhound

Begin with the basics of training the puppy and adult dog. Learn the principles of house-training the Otterhound, including the use of crates and basic scent instincts. Get started by introducing the pup to his collar and leash and progress to the basic commands. Find out about obedience classes and other activities.

Healthcare of Your Otterhound

By Lowell Ackerman DVM, DACVD

Become your dog’s healthcare advocate and a well-educated canine keeper. Select a skilled and able veterinarian. Discuss pet insurance, vaccinations and infectious diseases, the neuter/spay decision and a sensible, effective plan for parasite control, including fleas, ticks and worms.

Your Senior Otterhound

Know when to consider your Otterhound a senior and what special needs he will have. Learn to recognize the signs of aging in terms of physical and behavioral traits and what your vet can do to optimize your dog’s golden years. Consider some advice about giving special care to your pet in his golden years.

Showing Your Otterhound

Step into the center ring and find out about the world of showing pure-bred dogs. Here’s how to get started in AKC shows, how they are organized and what’s required for your dog to become a champion. Take a leap into the realms of obedience trials, agility, hunting tests and tracking tests.

Behavior of Your Otterhound

Analyze the canine mind to understand what makes your Otterhound tick. The following potential problems are addressed: aggression (fear biting, inter-canine and dominant), separation anxiety, sexual misconduct, digging, jumping up and barking.

KENNEL CLUB BOOKS®OTTERHOUND

ISBN 13: 978-1-59378-341-9eISBN 13: 978-1-62187-055-5

Copyright © 2007 • Kennel Club Books® • A Division of I-5 Publishing, LLC™

3 Burroughs, Irvine, CA 92618 USA

Cover Design Patented: US 6,435,559 B2 • Printed in South Korea

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, scanner, microfilm, xerography or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright owner.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cunliffe, Juliette.

Otterhound / by Juliette Cunliffe.

p. cm.

1. Otter hound. I. Title.

SF429.O77C86 2007

636.753’6—dc22

2006016300

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Photography by Carol Ann Johnson

with additional photographs by:

Ashbey Photography, Norvia Behling, Mary Bloom, Paulette Braun, Juliette Cunliffe, David Dalton, Isabelle Français, Bill Jonas, Kohler Photography, Petrulis, Kit Rodwell, Chuck Tatham and Alice van Kempen.

Illustrations by Patricia Peters.

The publisher wishes to thank all of the owners whose dogs are illustrated in this book, including Betsy Conway, Donna Emery and Miss Maria Lerego.

An Otterhound pack in action truly is a marvelous sight! The Otterhound is known for its extraordinary nose and distinct voice, traits that still define the breed today, whether or not used in a working capacity.

ORIGIN OF THE BREED

Used originally, as its name implies, to hunt otter, the Otterhound is a large, rough-coated scenthound with long ears and a melodious voice. There may be a link from the breed to the “otter dogges” used by Edward II, who reigned from 1307 to 1327, but it is likely that today’s Otterhound is an amalgam of several other breeds, among which the extinct Southern Hound is predominant.

The exact breeds involved in the Otterhound’s makeup perhaps will never be known for certain, but it would appear there has been some French influence and that, among other British hounds, the Bloodhound has played a major part. Certainly at the turn of the 19th century the Griffon Nivernais was involved, and we know also that a Griffon Vendéen was mated to a Bloodhound, producing a rough-haired black and tan hound called Boatman, whose blood subsequently ran in several kennels.

Otter hunting is a very ancient sport and also was a royal one, though methods have changed considerably over time. In 1360, there was mention of the use of spears to drown the otter; in 1681, all packs used spears. At that time, the hounds worked along the riverbanks and rarely entered the water. We also learn from old French books that nets and net chains were used in otter hunting. By the mid-20th century, poles ranging from 6 to 9 feet in length were used; this clearly was considered a “modern-day” improvement on the use of spears.

King Henry II (1154–1189) was the first recorded Master of Royal Hounds, but other royals of note were Kings John, Edward II, Henry VI, Edward IV, Richard III and Henry VIII; Queen Elizabeth I; and then Kings James I and James II. King Charles II (1660–1685) was the last recorded Master.

The Bloodhound is closely associated with hunting packs and prized for its superior scenting ability and is thought to figure in the Otterhound’s background.

In the mid-19th century, the writer Stonehenge said that no one but an expert could detect any difference between a large Welsh Harrier and an Otterhound. He considered that the only real differences were in the coat and the feet. Because of the Otterhound’s constant exposure to water, it needed more protection than that offered by the long, open coat of the Welsh Harrier. Stonehenge’s feeling was that by selective breeding of those hounds that best withstood the water, the Otterhound had come to possess a thick, pily undercoat of oily nature.

Harriers at Work, reproduced from a 15th-century illustrated manuscript titled The Master of the Game.

We can therefore assume that it was through the Welsh Harrier that Stonehenge believed the blood of the Southern Hound to run in the Otterhound’s veins, so now we will take a look at the ancient Southern Hound, to which our friend the Otterhound owes a large part of its ancestry.

THE SOUTHERN HOUND

It is likely that many hounds that hunt their quarry by scent have the Southern Hound somewhere in their blood. This was a hound that could hold a line for many hours, and its history goes well back into centuries past.

William Shakespeare seemed to have written of such a hound when he wrote in A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

My hounds are bred out of the Spartan kind

So flewed, so sanded; and their heads are hung

Taken from a painting by Willis, Wareful, a Southern Hound, appeared in Sporting Magazine in 1831. This ancient breed’s blood can be found in many of the scenthounds.

With ears that sweep away the morning dew,

Crook-kneed and dew-lapped like Thessalian bulls,

Slow in pursuit, but matched in mouth like bells,

Each unto each…

It was in 1576 that George Turberville, in his Arte de Venerie, gave a wonderfully descriptive and lengthy passage about the otter and the reasons for hunting it. He said that a litter of otters would destroy all of the fish in 2 miles’ length of river and that hunting them required great cunning. Otters then were clearly troublesome, for once they had destroyed the river fish, they would move to ponds from which they could not easily be removed.

Turberville also gave an account of how best to deal with otters, saying that initially four servants were to be sent in “with bloodhounds, or such hounds that will draw in the game.” Two were sent up river and two down river, on each side of the bank. In this way, he thought it certain to locate an otter, for the otters could not always stay in the water; they had to come out at night to feed by the water’s side.

Breaking Cover, a painting by Walter Hunt, shows a pack of Otterhounds on the otter’s trail.

It is believed that the Southern Hound’s lack of speed led to its decline, for most hunts-men preferred short, sharp bursts of activity to what was described as “a plodding day across country.” It was in the county of Devonshire, in southwest England, that the last pack of these hounds was kept.

This remarkable scene, photographed on the River Dove, shows an otter having been overtaken by the Otterhounds. Otters are very tenacious, and frequently one or more of the dogs became wounded in such struggles.

OTTER HUNTING

The otter seldom allowed himself to be seen, sometimes living in a burrow on a cliff by the sea, when its fishing exploits could extend as far as 7 or 8 miles up a river, usually at night. Other otters lived on the moorside at the head of a river, fishing down the river and back again, and it was otters in such regions that were more accessible to the hunter.

There was an interesting account printed in The New Sporting Magazine describing experiences of a South Devon otter hunt in the early 1840s. The Reverend Davies astonished old resident farmers when he began hunting near their homesteads, for when asked what he was doing, he replied, “otter hunting.” The farmers laughed and told him they had never heard of such an animal. Despite this, over the next 5 years the reverend killed over 50 otters within a mile of the farmers, so, although the otters had never been seen, they had certainly always been there.

Once the killed otter’s tough mask and pads were removed by the huntsmen, the body was thrown to the dogs. The otter hide seldom could be penetrated by the dogs, who killed their quarry by crushing it.

There were differing opinions as to how the otter should best be hunted and indeed the kind of hound that was best suited to the sport of otter hunting. The Reverend Davies actually favored the Foxhound, for he, like others, found that he enjoyed the dash of the Foxhound’s swimming at a great pace upstream when an otter had been dislodged from its holt. At around the same time that Rev. Davies had been hunting, the Master of the Dartmoor Hunt, Mr. Trelawny, used 14 or 15 couples of Foxhounds and 1 couple of rough Otterhounds, along with 2 or 3 terriers. This country squire would never admit that the regular Otterhound was as good as a Foxhound.

Others had differing views, for the Otterhound was very steady and methodical, feeling for a trail on boulder or rock, and, if he touched it, he would give tongue just once or twice. He could pick up a scent up to two days old but, if fresher, he became full of intent, moving a little upstream, crossing the river and perhaps back again, indicating by his manner that the quarry was near. A good hound, not hurried, was sure to find the quarry, even though the quarry may have been 3 or 4 miles from the starting point. Foxhounds, on the other hand, could miss all this.

Whether the Foxhound (shown here) or the Otterhound was the better hunting companion was a matter of opinion, but these two breeds often hunted together in the same packs.

The Otterhound was also by far the better marker. It was possible that the otter might be in a drain more than 100 yards or so from the river, and yet his outlet was at the root of some old trees perhaps 4 or 5 feet under the water. Foxhounds could easily have flashed over such a holt, but an experienced Otterhound was always on the lookout for such places. He would steady himself, swimming in the direction of the holt and turning his head to the bank, and, if necessary, lifting himself to the trunk of the tree and bending down to the water. If an otter were found, he would say so—in a voice like thunder! This would bring all the pack with delighted noise, and the otter would be so concerned that he would shift his quarters, without the hunters’ using a terrier.

EARLY PACKS

Otter hunting originally was associated with a mixed pack, and from some of Sir Walter Scott’s writings there is indication that even the Dandie Dinmont and other Scottish terriers played their part in the sport. However, from around the 1820s, the Otterhound was clearly a special breed. It was very carefully bred and continuously improved in uniformity of appearance.

The Otterhound’s magnificent nose and hunting instinct still are at the fore of the modern-day breed’s character.

Bubbles would be seen as the otter came up to vent, and the hunt would be in its fullest excitement. It was, of course, possible that the otter could outrun the pack by slipping downstream or into very deep water but, with good hounds and good huntsmen, the odds would be against the otter.

Certain huntsmen, Mr. Trelawny included, were adamant that the otter could not be touched in any way, but must be left entirely to the hounds. The Dartmoor Hunt was always considered a very fair one, but it has to be said that some people considered it more humane to finish off the prey. Trelawny’s was not the only hunt in Devonshire; there were three other notable otter hunts, those of Mr. Cheriton, Mr. Newton and Mr. Collier. Mr. Cheriton’s is of special interest to us because he hunted with pure-bred rough Otterhounds and was reputed to have some very good-looking ones.

Mr. Cheriton began hunting the northern Devon rivers in about 1850 and continued for at least 20 years, following which the Master was Mr. Arthur Blake Heineman, although the original name was retained. In the days of Mr. Heineman, there were between 10 and 15 couples of hounds, half of which were pure Otterhounds, the others Foxhounds.

Perhaps the greatest otter hunter of the 19th century was the Hon. Geoffrey Hill, a younger brother of Lord Hill. Major Hill was an ideal sportsman, himself over 6 feet tall and a powerful athlete, noted for the long distances he traveled on foot with his hounds. Most were pure rough Otterhounds, but they were not particularly large, with the dogs measuring about 23.5 inches and the bitches measuring about 22 inches. They had what were described as “beautiful Bloodhound type” heads, and their coats were thick with hard hair. They were big in both bone and rib and had good legs and feet. Some, though, had shorter coats than others, and it is possible that the hounds with the shorter coats had been cross-bred; however, all were in perfect command.

The Duke of Hamilton’s pack of Otterhounds, circa 1907.

Hill had an experienced eye and was remarkably quiet, but a wave of his hand was all that was needed to bring all of the hounds to any point he wanted. Although Major Hill rarely exhibited, some of his hounds were occasionally seen at Birmingham shows. They hunted through Shropshire, Staffordshire and Cheshire, into Wales, where they got their best water, so there was little time available for showing.

Mr. J. C. Carrick’s Carlisles were the most prominent Otterhounds in the latter half of the 19th century, for not only did he hunt with them but also represented the breed well at shows.

A meet of the Crowhurst Otterhounds in Sussex in the early 1900s.

MOVING INTO THE 20TH CENTURY

As the century turned, show entries for the breed were low, for the majority of hounds were needed to hunt in their packs, of which there were 21 in the UK by 1907. The Bucks hunted three days each week from Newport Pagnell, and Mr. Wilkinson’s pack was active at Darlington, while the West Cumberland pack worked in Cockermouth. In Ireland, the Brookfield pack had its headquarters in County Cork, and Wales was home to at least four active packs, the Pembroke and Carmarthen, the Rug, the Ynysfor and that of Mr. Buckley.

Covering most of the rivers in Sussex was the Crowhurst Otter Hunt with 16 couples, 7 of which were pure Otterhounds. Hunting on the rivers of Essex and Suffolk was the Essex pack, based at Water House Farm in Chelmsford. This was another example of a pack made up of half Foxhounds and half Otterhounds, with about eight couples of each. The Culmstock was a very old hunt, established by Mr. Collier and working in Somerset and northern and eastern Devon. The list goes on, with a pack from Chepstow showing a good deal of sport on Welsh rivers as well as in Gloucestershire and Hereford-shire, and in the New Forest about 15 couples of pure and crossed Otterhounds were worked.

Moving northward, the Northern Counties Hunt was not established until 1903, based on hounds from the Culmstock, Hawkstone and Dumfriesshire packs. They hunted over a very wide country from the Tweed and Tyne in Northumberland down to the Swale in Yorkshire, although other packs also had hunted these rivers previously. In the West Riding of Yorkshire, the Wharfdale had its kennels at Addington from 1905, but there had previously been a Wharfdale Otter Hunt Club that had invited hunts to its rivers. There also were the famous Kendal Otterhounds.

The sizeable packs used in the hunt required dogs that could work well together.

19TH-CENTURY THOUGHTS

At the turn of the 19th century, it was often said that continued exposure to water caused a good deal of rheumatism in the breed and that Otterhounds showed their age sooner than other dogs. It was also reputed that puppies were difficult to rear.

OTTERHOUNDS IN SCOTLAND

The packs most staunchly attached to pure-bred Otterhounds were reputed to be the Dumfriesshire and East of Scotland. The Dumfriesshire, established in 1889, had 16 couples. In time, they hunted all of the rivers in the south of Scotland as far as Ayrshire. By the early 1900s, it was believed that the hounds hunted by this pack were typical of those shown between 1870 and 1880 by Mr. J. C. Carrick and the Hon. Geoffrey Hill, Mr. W. Tattersall, Mr. C. S. Coulson and Mr. Forster.

The champion team of the Dumfriesshire Otterhounds with Mr. Wilson Davidson, Honorary Huntsman.

A pack boasting 11 couples of rough Otterhounds was established in the east of Scotland in 1904, and these hunted some of the rivers formerly hunted by the Dumfriesshire. They had been invited by the East Lothian Otter Hunt Club, which, with half of the Berwickshire, began this new pack.

It is very clear that as the 19th century turned into the 20th, the sport of otter hunting was markedly on the increase, with several new hunts being started. Hunting was considered to be a noble sport, and the eternal question seemed to be whether more pure-bred Otterhounds should have been used than was sometimes the case.

Many thought that for the real sport of otter hunting, nothing was as good as the pure-bred Otterhound. There was something so noble and dignified about him that, once one had seen a good Otterhound, the dog would never be forgotten. He needed to be a large hound, for the otter, sometimes called “the gypsy of the water,” was considered, for its size, to be the most powerful of all British wild animals. It was the inveterate poacher of Britain’s salmon streams, so people thought it proper that it should be hunted, though always in a sporting fashion.

DEVELOPMENTS FROM THE 1970s ON

The Otterhound Club was formed in 1978 with a founding membership of 80 people. The club’s first committee comprised several well-known names. This was the time at which the ban on otter hunting in England was introduced, because pollution had made both fish and otter scarce in the rivers. As the Otterhound’s usefulness as a working dog was brought to such a sudden end, it became of the utmost importance to preserve this magnificent breed, one that had long been part of country life and sporting pursuits.

Many of the people who supported the club were well known in the world of show dogs and also for their own rural activities involving other breeds, while many involved with Otterhound hunting packs added to their number. Although not perhaps interested in the show scene, it was important that active otter hunters recognized the importance of creating a club that would help to preserve their much-loved breed.

In Scotland, otter hunting continued longer than it did in England but, nonetheless, Captain John Bell-Irving, Master of the Dumfriesshire Otterhounds, allowed several of his hounds to go to private homes. Highly important in the conservation of this special breed was the fact that England’s The Kennel Club very kindly allowed free registration for pack hounds.

Winner of the very first Challenge Certificate (CC) to be awarded to the Otterhound in 80 years was Eng. Ch. Ottersdream Protector; this was in 1988 under Captain John Bell-Irving. The first Otterhound Club Championship Show, also in 1988, was judged by Mr. Leonard Pagliero, who although an all-round judge is considered a “specialist” in this breed. He awarded this same dog Best in Show, and Eng. Ch. Otters-dream Protector went on to become the first British Otterhound champion to gain his American championship title.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

At early dog shows, several Otterhounds took part and had substantial success. These dogs also had the most endearing names! In the 1870s, Booser, Stanley and Charmer were greatly admired. Other good dogs shown carried names such as Dauntless Lady, Thunderer, Bruiser, Stormer, Bachelor, Thrifty, Darling, Truthful and Swimmer, probably all living up to their names!

Although known as a “Minkhound” hunting pack, the dogs shown here are essentially Otterhounds.

Not a great number of Otterhounds have been registered with England’s Kennel Club since the formation of the Otterhound Club in 1978, so representatives of the breed still remain relatively few in number when compared with other breeds exhibited at shows. However, although otter hunting has been banned, the Otterhound is still used, often alongside others of mixed breeding, to hunt mink.

STARRING THE OTTERHOUND

In Holland, an Otterhound by the name of Banner starred in the musical Annie and her picture actually was featured on the record sleeve! While such publicity for a breed may have worried people in numerically strong breeds, this was not the case with the Otterhound, a breed in which so few dogs are bred.

An Otterhound pack works the water at a hunting event in Europe.

THE OTTERHOUND IN THE US

By Elizabeth Conway

Little is known about when the Otterhound first arrived in the United States, but some records indicate that the first hounds imported from the UK arrived in the early 1900s. Most of these hounds were used in the field, and registrations were not kept. The American Kennel Club’s (AKC) records indicate that Otterhounds were first exhibited at an AKC show in 1907.

THE OTTER’S EQUAL

To be equal to its prey, the Otterhound was said to need a Bulldog’s courage, a Newfoundland’s strength in water, a Pointer’s nose, a retriever’s sagacity, the stamina of the Foxhound, the patience of a Beagle and the intelligence of a Collie. What a magnificent dog is the Otterhound!

Mrs. McClelland, Mrs. Handy and Mrs. Kline appear to be the first known importers of the Otterhound in the United States, doing so in the 1920s—few litters, however, were born. It wasn’t until 1937 when Dr. Hugh Mouat, a veterinarian known as “the father of Otterhounds in the US,” began a serious breeding program. His first litter produced the first AKC champion, Bessie’s Countess, who acquired the title in 1941.

In his early years at breeding, Dr. Mouat faced many obstacles. A great number of his puppies died. Some were stillborn, while others perished from distemper, worms or a then unknown bleeding disorder called Glanzmann’s thrombobasthenia (fortunately, a genetic test is now available for this disorder and most breeding stock has been tested clear of the defect). Dr. Mouat continued to breed Otterhounds under the Adriucha prefix into the early 1960s.

Ch. Andel Milk Bank, shown winning a Hound Group at the Heart of America Kennel Club in 1978 under judge Tom Stevenson.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that there was more than one litter of Otterhounds registered in the United States during any given year. Records show that there were never more than 10 litters produced in the US in a year until 1992, when there were a record-breaking 13 litters born. The average number of litters born in the United States is 4 to 6 annually, with an average of 37 Otterhounds registered.

The Otterhound has never gained popularity like some “newer” breeds have when first introduced to this country. They have consistently ranked at the bottom of the AKC’s registration list of recognized breeds. Even with these small registration numbers, in recent years the Otterhound has done extremely well in certain performance events, including conformation, obedience and tracking.

In conformation, there are Otterhound entries at approximately 30% of all AKC shows, and Otterhounds place in Group competition more than 50% of the time. The first Otterhound to win an all-breed Best in Show was Ch. Skye Top’s Cedric Vikingsson, who did so in 1969. Several other Otterhounds have garnered this prestigious award with the most recent (at the time of this writing) being Ch. Scentasia’s Hostile Takeover, who has 23 Bests in Show to her credit.

A WORK OF ART

The Otterhound is a familiar breed in countless works of art. Vernon Stokes was known for his works that included Otterhounds, and an artist whose name is almost synonymous with the breed and with Bloodhound paintings is John Sargent Noble, RBA (1848–1896), who studied under Landseer. Some of his notable Otterhound paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy are Otterhounds (1876), The Otter’s Stronghold (1878), Otter Hound in Full Cry (1888) and Digging Out the Otter (1890).

Ch. Scentasia’s Hostile Takeover was one of the top Hounds in America in 2004. She is shown taking one of her 17 Bests in Show that year under judge Carol Reisman at Tuxedo Park Kennel Club.

Thirteen Otterhound owners organized the Otterhound Club of America (OCA) in August 1960. The American Kennel Club accepted the OCA as the Otterhound’s parent club 14 years later. Having never had more than 140 members, the club thrived with members enjoying great success in the venues available to them.

AROUND THE WORLD