Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

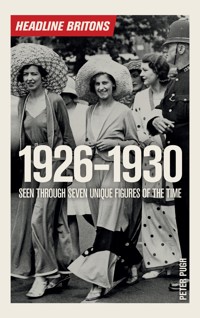

Headline Britons paints a unique picture of British life in the 20th and 21st centuries by re-examining some of the country's most notable characters. Each book covers a five-year span, telling the stories of a number of people who, in that time, stood out among their contemporaries. As the 1920s progressed and Britain tried to recover from the horrors of war, the country enjoyed a short postwar boom – seeing the development of household gadgets such as dishwashers, sterilisers and cigar lighters – but it did not last and soon unemployment grew. Peter Pugh shows in this book that despite the 'swinging twenties' being largely a myth, the decade was enlivened by mouldbreaking characters such as birth control pioneer Marie Stopes, father of the BBC John Reith, and Horatio Bottomley - perhaps the biggest business fraudster of all time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 196

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

About the author

Introduction

Monetary values

Timeline for 1920–25

List of illustrations

1 The Early 1920s

2 Baden-Powell and Boy Scouts

3 Horatio Bottomley and Fraud

4 Marie Stopes and Birth Control

5 David Lloyd George – A Country Fit for Heroes

6 Lord Reith – First Boss of the BBC

7 Bertrand Russell – What is the Value of Philosophy?

Index

INTRODUCTION

Every publishing season sees the launch of books on famous characters of the twentieth century and many high achievers have more than one book about them. For example, the number of books on Winston Churchill is in the twenties or thirties and recently there was another book on Clement Attlee.

This new series Icon is launching will cover the last 100 years of British history in five-year splits – the first two are 1921–25 and 1926–30 and, as well as giving the background, both social and economic, of those years, will concentrate on the interesting and often misunderstood characters that featured in them.

One of the main characters in this first book, 1921–1925, is Marie Stopes, the first person to set up birth control clinics (by coincidence I met her only son when interviewing his wife, who happens to be the daughter of the Dambusters bouncing bomb inventor, Barnes Wallis, about whom I was writing a book). Then there is the famous fraudster, Horatio Bottomley, and the founder of the Boy Scout movement, Baden-Powell. Another character is David Lloyd George, the Welshman who was the prime minister when we won the First World War and remained in charge until he was forced to resign in 1922, largely because he connived in the granting of knighthoods and other honours to people who paid for them. Another two characters who made a contribution to the early 1920s were the socialite Lady Diana Cooper and the philosopher Bertrand Russell. We will also look at John, later Lord, Reith, the first – and very autocratic – boss of the BBC.

MONETARY VALUES

Money and its value is always a problem when writing about a period that stretches over a number of years. Furthermore, establishing a yardstick for measuring the change in the value of money is not easy either. Do we take the external value of the £ or what it will buy in the average (whatever that may be) weekly shopping basket? Do we relate it to the average manual wage? As we know, while prices in general might rise, and have done so in this country every year since the Second World War, the prices of certain products might fall. However, we have to make some judgements. We can only generalise, and I think the best yardstick is probably the average working wage.

Taking this as the yardstick, here is a measure of the £ sterling relative to the £ in 2017.

Apart from wartime, prices were stable for 250 years, but prices began to rise in the run-up to the First World War.

1665–1900 multiply by 120

1900–1914 multiply by 110

1918–39 multiply by 60

1945–50 multiply by 35

1950–60 multiply by 30

1960–70 multiply by 25

1970–74 multiply by 20

1975–77 multiply by 15

1978–80 multiply by 8

1980–87 multiply by 5

1987–91 multiply by 2.5

1991–97 multiply by 2

1997–2010 multiply by 1.5

Since 2010, the rate of inflation, by the standards of most of the twentieth century, has been very low, averaging, until very recently, less than the 1997–2010 Labour government’s originally stated aim of 2.5 per cent (since reduced to 2 per cent). You don’t need me to tell you that some things such as telephone charges and many items made in the Far East, notably China, can go down in price while others, such as houses, have moved up very sharply from 1997 to 2017.

TIMELINE FOR 1920–25

- 1920 -

January

The League of Nations is formedThe 18th amendment to the United States constitution bans alcohol: the Prohibition era begins

March

The Automobile Association opens Britain’s first petrol station in Aldermaston, Berkshire

June

The Treaty of Trianon ends the redrawing of the map of Europe. Several new states have come into being, among them Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia

October

A state of emergency is declared as a miners’ strike begins to bite

December

Martial law is imposed in Ireland as the British army wages war on the IRA

- 1921 -

January

British tanks are deployed on the streets of Dublin

February

Unemployment in Britain passes the 1 million mark

March

Dr Marie Stopes opens a birth control clinic in Holloway Road, London

May

The British Legion is founded to help struggling ex-servicemen

June

Postmen stop making Sunday deliveries

September

Charlie Chaplin makes a triumphant visit to London, where he was born

November

Mussolini declares himself leader of the Italian Fascist party

December

The Irish Free State is founded. Six of the counties of Ulster remain part of the United Kingdom

Books

Women in Love by D.H. Lawrence

Crome Yellow by Aldous Huxley

The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie

Films

The Glorious Adventure

The Kid starring Charlie Chaplin

The Sheik starring Rudolph Valentino

- 1922 -

May

Dr Ivy Williams becomes the first woman barrister in England

August

Michael Collins, the Irish nationalist leader, is assassinated in an ambush

October

The British Broadcasting Company is formed.It aims to broadcast radio programmes ‘to the reasonable satisfaction of the postmaster general’Mussolini’s Black Shirts march on Rome to demand representation in the government; King Victor Emmanuel Ill appoints him premierDavid Lloyd George resigns as prime minister as the coalition government collapses. The new prime minister is Andrew Bonar Law

November

Licences for radios are introduced at 10 shillings (50p, or £30 in today’s money) a year British archaeologist Howard Carter unearths the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt

December

British troops leave the Irish Free State

Books

Ulysses by James Joyce

The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot

Films

Manslaughter

Robin Hood starring Douglas Fairbanks

- 1923 -

January

French and Belgian troops occupy the Ruhr; the move is intended to force Germany into paying war reparations

April

In the first Football Association Cup Final at Wembley, Bolton Wanderers beat West Ham United 2–0Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon marries the Duke of York, second son of King George V

May

Stanley Baldwin becomes prime minister after Andrew Bonar Law resigns due to ill health

September

Earthquakes rock Japan. Tokyo and Yokohama are levelled and 140,000 people are killedThe Radio Times is published for the first time

November

The tiny ‘national socialist’ party of Bavaria launches a coup. It fails, and the party’s leader Adolf Hitler is jailedInflation in Germany is such that a loaf of bread, which cost less than one mark in 1918, and more than a million marks a month earlier, now costs 200 billion marks

December

The chimes of Big Ben are broadcast by wireless for the first time

Book

The Ego and The Id by Sigmund Freud

- 1924 -

January

Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Soviet state, dies after a long illnessRamsay MacDonald becomes Britain’s first Labour prime minister

February

The BBC introduces ‘pips’ to pinpoint the exact hour

June

A wireless link is made between Britain and Australia

October

The Labour party bans communists from membership

November

The Labour government falls, and the Tories return to power under Stanley BaldwinThe Sunday Express publishes a crossword puzzle, the first for a British newspaper

December

The bones of Australopithecus africanus – the so-called ‘missing link’ – are discovered by Josephine Salmons in Africa

Book

A Passage to India by E.M. Forster

Play

The Vortex, a daring exploration of drug addiction by Noël Coward

- 1925 -

March

Daylight saving becomes a permanent institution

April

Winston Churchill, chancellor of the exchequer, announces a return to the gold standard in his budget

June

The colour bar becomes legal in South Africa. Black people, those of mixed race and Indians are banned from skilled labour

December

George Bernard Shaw wins a Nobel prize for literature

Books

Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler

Carry on, Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Trial by Franz Kafka

Films

The Gold Rush

Battleship Potemkin

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Robert Baden-Powell

2. Lady Diana Cooper

3. Horatio Bottomley

4. Harold Abrahams

5. Marie Stopes

6. Bertrand Russell

7. John Reith

8. David Lloyd George

9. Charlie Chaplin

CHAPTER 1

THE EARLY 1920S

The First World War, or the Great War as it was known until there was a second one from 1939 to 1945, ended in November 1918 and Great Britain, along with the other major participants, had to try to recover fully so that the people could resume the life they had enjoyed before 1914.

To begin with, more people were allowed to vote in general elections. The total number of electors had virtually doubled to 21 million. This was due first to an additional 2 million males – all those over 21 were now allowed to vote regardless of status – and second to 8.5 million women, as all women over 30 now had the vote.

Initially the economy boomed, but this did not last and by the middle of 1920 employers were cutting back. By Christmas many former soldiers were begging on the streets.

Furthermore, following the loss of about a million men during the four years of fighting, Great Britain suffered from the global influenza pandemic of 1918–19 which killed a further 228,000 Britons. Again, as in the war, most of the victims were young.

On the positive side, there was something of a housing boom in the 1920s as the middle classes were tempted out of the big towns into the supposedly idyllic countryside and the working class benefited from councils clearing the slums. Estates sprang up outside London, Birmingham, Leeds and Manchester. By the end of the decade nearly 1.5 million new homes had been built.

The upper classes – or ‘high society’ – did not seem to suffer the ravages that most had gone through in the four years of war. For example, Mayfair in central London was still full of large mansions which were run by staffs of 30 to 40 servants.

The class system was more entrenched in Britain in the 1920s than it is nearly 100 years later. Below is a summary of the five classes.

Aristocracy – the highest level of power, authority and social hierarchy, for example:

The royal family

Spiritual lords

Temporal lords

Great officers of the state such as baronets, knights and country gentlemen

Upper middle class – the administrative level with considerable authority, for example:

Factory owners

Bankers

Doctors

Lawyers

Engineers

Clergymen

Lower middle class

Small-scale businessmen

Merchants

Civil servants

Working class

Labourers

Factory workers

Seamstresses

Miners

Sweepers

The poor

Living on charity

Generally people knew which class they were in and behaved accordingly.

Meanwhile, across all social classes, British women’s lives had changed immensely. As A.N. Wilson wrote in his book After the Victorians 1901–53:

Women after the war looked different. They dressed differently. Readymade frocks became cheaply available. Ankle-length skirts had risen to the calf by the end of the war and to the knee by the time of the fall of Lloyd George. Hair could be cut short. Veils had vanished. Young women no longer forced themselves into bone corsets. ‘The freedom you have got with regard to dress is worth the vote a hundred times over,’ said Sir Alfred Hopkinson, addressing the young women of Cheltenham Ladies’ College, among them my mother, in the early 1920s. Whatever their class, they were never going to go back to the lives of their heavily corseted mothers and grandmothers. By 1923 there were four thousand women serving as magistrates, mayors, councillors and guardians. In 1919 they were admitted to the legal profession, and Oxford University allowed them to take degrees. (Cambridge did not follow suit until after the Second World War).

And according to the first edition of Good Housekeeping magazine in March 1924:

Any keen observer of the times cannot have failed to notice that we are on the threshold of a great feminine awakening. Apathy and levity are giving place to a wholesome and intelligent interest in the affairs of life, and above all in the home. There should be no drudgery in the house ... the house-proud woman in these days of servant shortage does not always know the best way to lessen her own burdens ... The time spent on housework can be enormously reduced in every home without any loss of comfort, and often with a great increase in its wellbeing and its air of personal care and attention.

Diana Cooper

Lady Diana Cooper, originally Lady Diana Manners, was perhaps the most famous and glamorous member of the British upper class in the 1920s. Born in 1892 to the Duke and Duchess of Rutland, she was part of the ‘Coterie’, a group of English aristocrats and intellectuals active in the years leading up to the First World War. Many members of the Coterie were killed in the war but she married one who survived, Duff Cooper, a Foreign Office official.

During the war Diana worked as a nurse and as an editor of the magazine Femina, and wrote a column in the newspapers of Lord Beaverbrook in the early 1920s.

Diana was somewhat chaotic about money. This is what Philip Ziegler wrote in his biography of her:

Money was urgently needed if their life-style was to be maintained, still more if Duff were to abandon diplomacy and take to politics. Many projects were mooted. The Sunday Evening Telegram announced that Diana was to become a dress designer, then that she was to set up as an adviser in house decoration – ‘Can’t you imagine how the profiteeresses would rush to consult her at ten guineas [about £600 in today’s money] a time?’ Gilbert Miller offered her a share in the management of a theatre at £500 [£30,000] a year, the proposition sounded hopeful but came to nothing. Then she was invited to join the board and subsequently become Chairman of a company manufacturing scent. She was to receive £500 a year for doing nothing, and gleefully accepted. The company crashed, the managing director was arrested, Diana threatened with prosecution for fraud and obtaining money by false pretences. Duff was sympathetic but as ignorant in business matters as his wife. Diana was grilled in court. How much money had she put into the company? None. How did she think she could be a director in that case? She didn’t know. Had she never been educated? Well, not to speak of. Her patent ignorance of matters financial and her failure to gain a penny from the enterprise saved her from prosecution, but she left the court brow-beaten and abashed.

On 13 November 1920 it was announced that 28-year-old Diana Cooper – ‘the most beautiful woman of the day’ – had at last agreed to appear as a film actress. A handsome offer had been made to her by the film director Stuart Blackton. Her first film, The Glorious Adventure, set in the days of King Charles II, was shown on 16 January 1922 at the Covent Garden theatre. Lady Diana said:

I am so happy. A good many people thought I was not interested in undertaking film work but they little knew how really interested in acting I have been for years.

A revolution in leisure and technology

The world of film was growing apace, and its effect on the lives of ordinary people was profound. For example, this is what Irish author St John Ervine said about the great Charlie Chaplin in February 1921:

I have a most vivid recollection of the first occasion on which I saw a Chaplin film. It was in France. A party of very tired and utterly depressed men were moving down from the ‘line’ to ‘rest billets’ after an arduous spell in outposts. The weather had been very hard and bitter, so that the ground was frozen like steel, and many of the men had sore feet and walked with difficulty. I remember the party losing its way in a road where misery had settled down so deeply that no one swore.

In that state of dejection the lost party staggered into the rest billets at three o’clock in the morning and were told that, at the end of the week, instead of the promised Divisional rest, they would receive orders to return to the line! Next evening, after tea, with some recovery of cheerfulness, the men went off to the big barn, in which the Divisional Concert Party gave its entertainments. There they sat, massed at the back of the barn, looking strangely childlike in the foggy interior, and listening without much demonstration to some songs. Their irresponsiveness was not due to inappreciation, but to an overwhelming collective fatigue, and to the dreadful loathing of one’s kind that comes from continuous association in congested quarters. Then the singing ended and the lights were diminished and the ‘pictures’ began. On the screen came the shuffling figure of Charlie Chaplin and a great welcoming roar of laughter broke from them. That small, appealing, wistful, shuffling, nervous figure, smiling to disarm punishment, had only to show himself, and instantly a crowd of driven men remembered only to laugh. That is an achievement which is very great.

At the same time, household gadgets were being developed and became common. As early as 1920 the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition offered the vision of an all-electric home featuring a dishwasher, baby-milk steriliser, massage vibrator and cigar lighter. All of these electrical inventions meant that a labour-saving home could function without servants.

All this cost money, and many people were working long hours which included overtime, although this was not necessarily paid.

Offices were changing. Open-plan offices became common and noisy with clanging typewriters, telephones and Gestetner or Roneo duplicating machines. And offices were no longer full of just men. There were female secretaries, typists, telephonists and clerks.

And transport was changing too. Before the First World War motor cars were only owned and driven by the rich and, when the war ended, there were only 160,222 vehicles on the road in the UK. However, during the 1920s mass production of cars by Ford, Austin and Morris brought down their price so that the middle classes could afford them. In 1922 there were about 300,000 licensed cars in Britain. By 1929 this figure had increased to over 1 million. The plunge in price helped enormously. In 1920 a very modest Austin cost £495 (about £30,000 in today’s money). In 1923 the new Austin Seven cost £225 and by 1930 it was only £125 (£7,500). Furthermore, the introduction of hire purchase meant that the owner could pay by instalments. And by the end of the 1920s the motorised lorry had largely replaced the horse-drawn cart in delivering products to shops on the high street.

Another device whose use grew dramatically in the 1920s was the telephone. In offices, especially those of old professions such as banking and the law, communication by letter was still important, with letters costing only 1½d (37.5p in today’s money) to post – and there were three mail deliveries a day. Sometimes a letter posted in the morning would be delivered at 5pm the same day.

In 1927 there were about 500,000 telephones in Britain and by 1929, 1.5 million. Nearly all calls had to be made via an operator and overseas calls were fiercely expensive. An operator at the Ritz Hotel was startled to find that a famous American singer had rung New York and the charge was £75 (or £4,500 in today’s money)!

The other means of communication, newspapers, also spread to virtually the whole population with the Daily Express, Daily Mail and Sunday’s News of the World enticing purchasers with photographs and banner headlines on their front pages. The Times did not carry photos on its front page until the mid-1960s.

As we have seen, another form of entertainment which came to prominence in the 1920s was the cinema and this was the heyday of the silent movie.

Many people went to the cinema at least once and often two, three or even four times a week. Apart from the enjoyment it was very cheap. For a ‘tanner’ (6d; 2½p or £1.50 in today’s money) – or only a third of that if you were prepared to sit downstairs at the front in the ‘fleapit’ – you could see a newsreel, the feature film, a second feature film, some advertisements and probably a cartoon. It was the era of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, the Keystone Cops and Laurel and Hardy.

For those not completely enamoured by the cinema there was sport and the 1920s brought some exciting moments. In fact, sport had already been growing in importance earlier in the twentieth century. For example, London hosted the fourth modern Olympic Games in 1908 and, the previous year, the English Rugby Football Union bought a ten-acre site at Twickenham.

When peace came at the end of 1918 many Britons relished the chance to participate once again in their chosen sports; association football became the game of the ‘masses’ while rugby and golf were the games of the middle and upper classes. In association football, the number of teams in divisions 1 and 2 expanded and a third division was added.

The FA Cup final became a must-go-to event and Wembley stadium played host for the first time in 1923. Furthermore, in the same year the custom of the reigning monarch attending the final and presenting the cup to the captain of the winning team was established.

Cricket also gained popularity. This is what Keith Robbins wrote in his book The Eclipse of a Great Power:

Cricket remained essentially an English game, although Glamorgan became the last county to join the championship – usually near the bottom. It was believed that the Scottish summer was so short that players never had time to get padded up. Test cricket involved ‘England’ against visiting teams, though the Englishness of the side did not require the exclusion of the occasional Scot or Indian. Australia remained the prime opponent and, with only short intervals, established apparently effortless superiority. Donald Bradman proved very difficult to get out.

Fame came to many cricketers, and other sportsmen, but fortune did not normally accompany it. That was a stage in the evolution of sport which was still to come.

Chariots of Fire

The 1924 Olympic Games in Paris elated the British thanks to Harold Abrahams winning the 100 metres against some very strong American opposition, and Eric Liddell winning a gold medal in the 400 metres having refused to compete in his best event, the 100 metres, because he was a strong Christian and the heats were run on a Sunday. The events surrounding these games were immortalised in the film Chariots of Fire, conceived and produced by David Puttnam at the beginning of the 1980s.

The real-life background story to the film is worth discussing here as it demonstrates some significant facts about 1920s British society. The film shows both that there was plenty of anti-Semitism in Britain in the 1920s, and also that Sunday was still taken very seriously by many Christians.

In 1919 the Jewish Harold Abrahams went up to Cambridge University, where he soon encountered anti-Semitism from the teaching staff. Nevertheless, he became the first person to complete the Trinity Great Court Run – the feat of running round the college courtyard in the very short time it takes for the college clock to strike twelve. Abrahams also scored a number of victories in running competitions.