7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

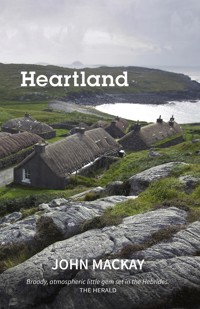

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Hebrides

- Sprache: Englisch

A man tries to build for his future by reconnecting with his past, leaving behind the ruins of the life he has lived. Iain Martin hopes that by returning to his Hebridean roots and embarking on a quest to reconstruct the ancient family home, he might find new purpose. But then he uncovers a secret from the past.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 298

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

JOHN MACKAY was born in Glasgow of Hebridean parents. The Road Dance, like his other two novels, Heartland and Last of the Line, is set on the Isle of Lewis. John is the anchorman on Scottish tv’s evening news programme Scotland Today and has reported on many of the major news stories in Scotland in recent times. He is married with two sons and lives in Renfrewshire.

John MacKay on Twitter: @RealMacKaySTV

By the same author:

The Road Dance, Luath Press, 2002

Last of the Line, Luath Press, 2006

Heartland

John MacKay

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2004

Paperback 2005

eBook Edition 2012

ISBN (print): 978-1-905222-11-7

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-11-3

© John MacKay

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Glossary of Gaelic terms used in Heartland

Chapter 1

THIS WAS HIS LAND. He had sprung from it and would return surely to it. Its pure air refreshed him, the big skies inspired him and the pounding seas were the rhythm of his heart. It was his touchstone. Here he renourished his soul.

The landscape was eternal, the rock smelted at the beginning of time. But the mark of man was all around. Where once there had been trees, now there was none. Science said it had been the change of climate, but he preferred to believe the legends that the Vikings of a thousand years before had scorched the earth.

Out on a promontory there was a pile of stones that in a different millennium had been the hideaway chapel of a hermit priest. A large stone slab on the moor covered the resting place of an unknown seaman from another century. Regular folds in the ground where the grass grew greenest had been the food-providing lazybeds of his forebears. Carefully constructed cairns stood on the hilltops, tributes to people lost in time. And all about, ruins of the old houses, where once there had been ceilidhs and warmth and life.

With no forests, the wind was free to roam, swooping, swirling and unceasing. Sometimes he imagined the spirits of those long gone were borne on the breezes that kept the constant company of the old stones. To the eye it was a place of emptiness, where all who mattered were gone and time had passed on. Yet on another plane it was alive, vital with forces beyond understanding.

The peat was still sodden from the spring rain, the water gurgling through the earth beneath his feet, sometimes gathering in an oily sheen in the hollows and dips. There would be no rain today though. The ocean stretched away beyond sight, an overwhelming vastness beneath the blue, cloudless sky.

Iain Martin was at the old house, on a hill overlooking the village road as it merged into the foreshore of the bay. From this point you could see to the horizon with its allure and promise, and behind, the houses of the district haphazardly dotted along the general line of the road. It was where the unknown and the familiar came together. Among the ruins of lives long gone, the silence and isolation could be both soothing and forlorn.

The sea lapped and lolled, but he well knew how treacherous it could be. While the land was his comfort, the water scared him. How dark and awesome it could turn. For as long as man had fished, the ocean had gathered payback. Iain’s generation had been no different and the memory of how his friend Rob had been lost stuck to him like a limpet.

Iain should have been on the boat with his friends, but there were books to be studied for his exam resits. Rob had strolled off with Neilie towards the sea, smiling as ever, his rubber boots flapping against each other at the knees. That sound had stayed with Iain. He wondered whether the water-filled boots dragged his friend down while the breath seeped away from his lungs. And though Neilie had cursed Iain for backing out of their planned trip and cajoled him about getting fresh air in his head, Rob had been his usual easygoing self. There were fish to be caught, beer to be drunk and life to be enjoyed. Even now, Iain could see Rob’s face framed by a thick black fringe and sideburns, his dark eyes alight and a smile pulling constantly at his mouth. Living for the moment, that was Rob. And it was a consolation in the aftermath, as he searched for any fragment that might ease the loss, that Rob had truly lived each day.

The urgent voice of Iain’s father had penetrated the deep of his sleep, jerking him into consciousness and a life that would never be the same again. His dreams of Catriona had been disturbed by the distant ringing of the phone. A light must have gone on and as he came out of his slumber he heard his father’s monosyllabic voice. His father was never comfortable speaking on the phone, but Iain remembered him sounding particularly terse that night.

‘Yes. Oh. Right away.’

Then the voice had called to him. Something was wrong at the shore and they were needed. Groggy from sleep, Iain stumbled from his bed into the cold of his room and pulled on his jeans and a T-shirt. His brother, Kenny, was slower to stir. As Iain emerged from his room his father had nodded at his clothes and said grimly, ‘You’ll be needing more than that.’

His mother, Mary, had stood at the door, her face lined with worry and her dressing-gown pulled tightly around her. She had been standing beside her husband throughout the short telephone call, a little irritated that he had got to it first, and anxious to hear what was wrong at that time of night.

‘Someone’s missing,’ Iain’s father had said. ‘One of the boys raised the alarm at Dan’s. That was Nan asking us to go down and help.’

‘What boy?’ asked Iain.

‘She didn’t know. Dan just called to her before going. C’mon, we need to be quick.’

Even then, as he pulled on an old oilskin and his boots, Iain couldn’t quite believe that it might be one of his friends.

The wind barged in as soon as they opened the door. When they stepped away from the protection of the house, the rain nipped their faces hard. Iain and Kenny might be approaching their twenties, with all the confidence that brings, but at times like this they still looked to their father for leadership. They could bring youth and strength, but that would be no match for the understanding and sense that came with experience.

Dan and Nan’s house sat at the final bend in the road before it twisted down to the shoreline. Nan was standing outside waiting for them.

‘They’re all down at the shore, but there’s nothing to see. I’ve phoned the coastguard.’

‘Right, Nan,’ said their father.

‘I think I should maybe stay here in case anyone phones.’

‘Yes. That’d be best.’

The sea was thrashing high up on the shoreline. They could make out four figures. Two of them were pulling the boat up beyond the reach of the waves. The boys’ father flicked on his torch and they all looked round. It was Rob who was missing. Dan clattered over the pebbles to meet them.

‘Rob’s gone. Overboard. Neilie managed to get the boat back, though I don’t know how.’

Iain ran to his friend. Neilie had a small whisky bottle in his hand and he was soaked through, his hair plastered so flat that the skin of his scalp could be seen white against it. His whole body was trembling.

‘Neilie, what happened?’

Neilie shook his head, unable to speak.

Iain’s father came over, speaking loudly over the wind.

‘You need to get up to the house and get dry.’

‘No,’ protested Neilie, ‘we’ve got to get him.’

‘We’ll get him. But if you don’t get warmed up then we’ll have another problem.’

‘Dan’s given me a shot of this. That’ll warm me.’

‘Neilie,’ Iain’s father commanded, ‘get up to the house and get warm. There’s others will look for him. Iain, help him up.’

Iain hauled his friend up and led him unsteadily back up the shore, their feet slipping on the pebbles. A huddle of villagers had gathered, lashed by the rain and pulled by the wind. Clips of raised voices carried, indistinct but concerned.

‘Will they find him?’ Neilie asked desperately.

‘They’ll find him,’ reassured Iain. ‘I’m sure of it.’

The hours of the night had passed too quickly, taking hope with them. By morning, the storm had blown out and the sea ceased to flay the land. In the bleak light of a grey dawn all was settled, except for figures scrambling over the cliff edges looking for something, for anything, and the men in the lifeboat scanning the sea back and forth outside the bay. From wherever any of the searchers looked back, they would have seen the woman standing at the rim of the shore, a blue nylon nightdress flapping beneath a heavy anorak. Rob’s mother had come as soon as she’d heard, taking time only to grab one of her son’s jackets for protection. She had sunk deeper and deeper into its folds as the hours passed, refusing to abandon her watch. By the end of hope she was withdrawn into herself.

Rob’s father had desperately scoured the cliffs for days and it was commonly held that his spirit died the night he knew his boy was not returning.

At Nan’s house, Neilie had been dried and warmed. His own mother had rushed in, barely knowing what to do in her relief, pulling his head to her as the tears coursed down her face. Neilie’s father carried on to join the search, as relieved as his wife at learning their son was safe, but unable to show it. Iain went with him, leaving Neilie in the care of the women folk.

When Iain returned later, Catriona was there, her young face drawn and pale. She was seated on the floor beside Neilie, her hand holding his as he drank tea and tried to stop shivering. When Iain came in she, like all the others in the room, could immediately tell from his face that there was no news.

‘What will we do without Rob?’ she had asked tearfully when she saw him to the door on his way back to rejoin the search.

The four of them, Catriona, Rob, Neilie and Iain, had been the youth of a fading community. With few alternatives for playmates, Catriona had tagged herself determinedly to them. They had resented her at first, but when she proved over time to be their equal at running, climbing and fishing she became an honorary boy with them. As they grew, she blossomed and Iain’s heart was hers for the taking.

The faces of the older men were set grim. In times before, when more fishing was done from these shores, searches for people lost overboard – for entire crews – had been more frequent and so often in vain. None of those who knew of the grip of the sea carried much hope. But they tried painstakingly for one who was their own. Every cleft of cliff was examined at great risk and the boat was even set on the water again. But the silence of their returns said enough.

Neilie recovered. Physically he was in his prime, young and strong. If there were any scars on his mind he hid them well, but never in all the years since had he ever talked to Iain about the loss of their friend.

Rob’s mother, widowed two years later, had endured until her death, but no more than that. The boys made a point of calling on her and she always welcomed them, but they could see the emptiness in her eyes. Her heart was burdened with thoughts of her only child, lost to the sea.

The night it happened remained clear for Iain. His memory of the subsequent investigation and inquiry was a jumble. One report recorded the good fortune and skill that allowed Neilie to pilot the boat back to shore with only one oar and raise the alarm. Neilie had become quite the local hero with his stories of the snarling sea and the jagged rocks. People marvelled at his seamanship and said it was a miracle he had got back to land at all.

Rob’s body was never found, its fate not dwelt upon. How fine, Iain had pondered in darker moments, were the contours of fate, how one could be lost and another saved. What had taken Rob overboard and left Neilie to survive? What thought, step or movement had placed Rob in the hands of eternity? He had heard the same asked by the veterans of the Great War, whose time was drawing to a close during his youth. A bullet had grazed the back of his own grandfather’s head, he remembered.

‘I don’t know why I turned,’ the old man would say. ‘Nobody called me, but I turned my head to the side. That’s when, crack!’ And he would illustrate with the tip of his finger how the bullet had clipped the skin off the back of his head.

The veterans were always reluctant to talk of those times, but sometimes they did and always they questioned why they had survived and their comrades had not. They had no answer for it.

Predestination is what the church had told them and the generations that followed. It was all part of God’s design. You lived your life as God planned it for you. At the memorial service for Rob the minister had reinforced that view. It would serve no purpose for anyone, and he meant Rob’s parents and Neilie himself, to agonise over why one had been taken and one spared. It was the Lord’s choosing and it was not for mortal man to understand the Wisdom of His way.

His grandfather believed that to be as good an explanation as any, but it never rested easily with Iain. Why live your life at all, if that were so? And especially, why ponder the great choices of faith and life when there was no choice at all?

When he was younger, he would sometimes be dismissive of the committed faith of the old folk around him. He had been the first of his family to attend university, although Kenny came soon after and his sister Christine would follow. My, my, the university! What store his parents laid in the wisdom to be received there and the opportunities it would open.

His studies had made him disdainful of the certainties with which the previous generations had lived their lives. Now he wasn’t so sure. His forebears had lived life in the raw, dependent upon the seasons and exposed to the relentless realities of a hard life. For so long in their youth, his grandfather’s generation had walked daily with death and horror. What arrogance was it that made him think his learning from books was superior to theirs?

He was never sure whether Neilie was bothered with such preoccupations, despite having been so close to eternity. Probably not. ‘Get up to that bar,’ was his philosophy.

Nearly twenty years on, Iain was home again, watching the deceptive lap of the water. How peaceful it seemed and yet how remorseless it could be.

From his vantage point he could see the headland of the bay facing onto open sea. It was said that a baby had been thrown into the sea from there, a newborn boy. Iain had heard the story often from his mother.

‘The poor child was washed up on the shore, all wrapped up. Oh, it must have been terrible. His mother couldn’t have been in her right mind to do something like that.’

‘Who was she?’

‘No one knows. Some said she wasn’t from the village, that he’d been put in the sea further up the coast, but my mother remembers them searching up on the cliffs around here. The old captain who found him told my grandmother that the child hadn’t been in the water long enough to have come from somewhere else. It must have been a local girl.’

‘And they never found out who?’

‘Not for sure. You remember Kirsty Seanacharrach?’

‘Yes, in at the shore? Died just a couple of years ago?’

‘Well, and I shouldn’t be saying this, but she had a sister Annie who died when she was young. She had that terrible flu after the war. Anyway, some thought it was her. They had the police over and everything, but they never did find out.’

‘Why did they think it was her?’

‘My granny said there had been doctors at the house at the time, but nothing ever happened. I suppose it was just rumour.’

‘What about Kirsty Seanacharrach? Did she never say anything?’

‘No. She was very nice. Remember she always gave you children sweets when you were going down to the shore? She was very quiet, Kirsty, she didn’t really speak much. But here’s the thing, and I was only just hearing of this.’ His mother became almost conspiratorial. ‘The baby was buried in the cemetery. There was no headstone for the wee soul, but sometimes you’d see flowers at this spot in the graveyard. Nobody knew who placed them there, but now and again a posy would be left. Well, just recently a woman in the church was saying to me that she’d only just noticed, but since the old woman died there have been no flowers on the child’s grave.’

‘Really? You mean, they think old Kirsty was the child’s mother?’

‘Who knows? These secrets all die with the dead.’

Iain remembered that clearly now. Beneath his shaking legs lay a skeleton, exposed to the skies for the first time in how long? Another secret only the dead knew?

Chapter 2

THE DAY HAD STARTED with a spade in his hand and peace in his soul. Now he was trembling, staring down on the exposed grave of someone unknown.

On a plateau just before the land dropped finally away to the sea, stood the roofless remains of an old blackhouse. For half a century it had been open to the wind, the rains and the storms of the ocean and still it stood, defiant and enduring. Now it seemed as elemental as the natural forces that had sought to destroy it for so long. The construction of grey gneiss rock had been hewn from the land around and the uneven stones were bound together, not by mortar, but by the intricate assembly of the skilled builder. Iain was a direct descendent of that builder.

Nature’s force had not yet made it succumb: in time far distant, the land would more subtly reclaim its own. The house was overgrown inside with grass and moss and carpeted with buttercups and bluebells. A platform of turf had formed around the top of the steadfast walls.

Time had swept over the house and left it behind. Yet the changes that had encouraged its people to move on to greater comforts could now be utilised to bring it back to life. Iain would be the one to complete the circle.

It was easy to get romantic here, to absorb the glory of nature – the awesome Atlantic, the moorland flowers and the birds gliding on the wing. But that would be to ignore the gloom of winter when depression could sink a lonely soul. It would be to forget that sorrow seeped through the soil. Economic fragility had forced so many away. There were those who had left at the first opportunity, eager to escape the claustrophobia of everyone knowing who you were and who your people were.

Adventure, education and opportunity had all been reasons for leaving, but more than anything it had been love. Lost love. Iain had fled from having to face that love every day, knowing that it could not be fulfilled.

Now he was home again, home for good. There was no denying the bonds of blood and soil. He had always known the island would be his home again, that he would return to the very land that his family had abandoned two generations before.

‘Why would you want to do that?’ his mother, Mary, had asked, taken aback. ‘You’d be better to build yourself something new, if that’s what you want to do. The old place is best left alone.’

‘I thought you would understand, Mam. You of all people.’

‘Well, I don’t. I can’t see that it makes sense. No one has lived there in sixty years. And they had good reason to leave. Why would you want to live in it now, even if you could?’

Neilie was more to the point.

‘You’re pissed!’

Iain smiled when he remembered the conversation in the hotel bar.

‘The only people who come up with daft ideas like that are those from the south who have more money than sense,’ had been Neilie’s firm opinion. ‘They come here and try to change everything and then when they realise it’s not the good life, they’ll bugger off back to where they came from. But you? Bloody hell! You’ll forget about it in the morning.’

‘Why not?’

‘Why not? Loads of reasons, but here’s two for starters. Your old lady has a house with a roof and windows for when you come home. Second of all, the place is a ruin and you aren’t a builder. Now stop talking crap and get up to that bar.’

They would come round in time. It wasn’t the good life he wanted. He had been born and raised on the island and he knew that it was no idyll. What he wanted, what he really needed, was peace. Everything he had done since, his career, his marriage, his whole lifestyle had been an attempt to fulfil ambitions that he had absorbed from other people, not what was truly his own. He was done with running and he was home.

Neilie was right. He wasn’t a builder and he didn’t know where to begin, but stripping the house down to its basic structure and then reconstructing it, you didn’t need to be an analyst to see the therapy in that. The essentials of his life were here. This is where he could be himself. He knew that now.

The ceremonial cutting of the first sod the previous day hadn’t worked out quite as he had imagined. The spade couldn’t cut cleanly through the soil because of the tangle of grass and roots. It barely penetrated any earth at all: first evidence that it would be a long slog ahead.

Iain had cautioned himself against getting too carried away with his project. He was highly aware of the symbolism of cutting the first turf. He would not work so hard the first day, just make a start. Then he would bring the barrow down and make real progress. He had toasted his life ahead with a slug of whisky from a hip flask before grabbing the spade. The whisky was still on his tongue when the jarring from the spade rattled up his spine. The rewards of living in such a landscape were glorious, but nothing had ever been won from it without backbreaking graft.

He took a breath and jumped heavily onto the spade. Then again and again. Finally it severed through the grass and weeds and he felt the blade sink beneath him. Sweat smeared his forehead and his lungs dilated.

This was his first challenge. He could stop now, walk away and laugh at his foolishness. Or he could thrust his spade down again. The motivation in ages past would have been dig or starve. Iain was spared that. His choice was between reason and pride, realism and dream. He stepped back, grasped the hip flask from his backpack and took another swig of the uisge beatha, the water of life, then wiped his forearm against his head. Lifting the spade up, he drove it down, lunging from his shoulder.

That same shoulder ached four hours later as he soaked in a bath drawn by his mother. Not just his shoulder, but his neck, his back and his thighs. This was exhaustion like he had not experienced in many a year. In his former, office-bound existence, the fatigue of routine and long hours had never matched this. As a young man back from the peat cutting, the prospect of a few beers at the hotel had been enough to reinvigorate his youthful body. With middle-age not so far ahead now, it would take longer to recover, but he reassured himself that his muscles would become used to the effort.

Despite the aching and the nipping of the blisters on his palms, he had a feeling of achievement, satisfaction in a hard job well done. He had worked out a technique and had been shifting far more turf by the end of the day than at the beginning.

On day two he had uncovered the remains of the original clay and stone floor of the house. Perhaps he might find where the old open fire had been, the focal point of the house. At the beginning of the century, when the family was getting a little more prosperous, a chimney stack had been built at the top end. No more smoke swirling around the interior all day, wisping through the small hole in the roof and blackening the thatch. What a step forward that must have been! A peat fire would burn again in that hearth, but Iain liked his comforts and so electricity would fire his central heating too. For that, the old floor would have to go.

The blisters still bothered him, but the ache in his muscles receded more quickly now and his stamina was improving. Developing a steady rhythm he had removed most of the turf and had used the barrow to pile it outside. It was remarkable how absorbed he could become. The time would fly. Sometimes he missed the breaks he had set for himself, but then he could sit with his sandwiches, made from black-crusted bread, and his whisky, and feel that real progress had been made.

Already the house seemed familiar, the contours of the stones and the patterns of lichen on them. The construction was so different from the straight, geometric lines of bricks and cement. The big stones were the key, some of them too big for one man to lift alone. None was a regular shape, the edges weren’t straight and the corners ranged through all the angles from acute to obtuse. Smaller stones were packed into the gaps and from this complex jumble emerged a sturdy structure which was a work of art in its own way. It took a craftsman to see how this clutter of forms and shapes could be fused together to create something so lasting.

When he had finished, the floor of what had been the original living area of the house was cleared. An additional room had been built on the seaward side and that would be next. At the far end there was an opening into a smaller space which would have been the animal byre.

Iain stood with his back to the chimney stack and surveyed his work. This was the very floor that had been the hearth of his forefathers, the surface on which they had walked, cooked, talked and lived their lives. What joys and sorrows had these walls witnessed? More than one hundred and fifty years of one family’s history. Birth and death, joy and loss. The cries of newborns and the final sighs of the dying. It was all around him. He could feel it. It was part of who he was. They lived on through him.

How often had his great-grandmother swept this floor? In the one faded photograph his family had of her, her face was weather-beaten, her hair scraped back in a severe middle parting, her dress black and her gaze solemn and steady. She had been born only yards from here, had never left the island, and in this house she had passed on to eternity. The village had been her world. When she died, the house had been closed up.

By day three he was ready to break through what remained of the clay floor, wielding a pickaxe to get going. Everything had been built to last, in an expectation of endurance alien to the mindset of Iain’s generation, by people who had suffered clearances and uncertainty of tenure. Finally, the family secured land they could call their own. This house was testament to that faith, solid and enduring. Here, where the Atlantic made landfall from its restless journeying, they had torn rock from the ground, borne boulders from the shore, and built a home. Fish bountiful in the sea, crops in the ground, family and faith. For a few, too few golden years, that is how it was.

Politics, economics and war had changed it all, and then changed it again and again. But the house was a memorial to his great-grandfather’s belief that he had found his heartland. Iain’s heart told him the same.

The core of the house would remain, but much would have to change. It was easier once he had made the initial penetration of the clay. That gave him leverage and he worked at it, using the pick to break it up and then scooping up the fragments with the shovel and dumping it in the barrow. He would keep the rubble and reuse it once he had dug further down.

Swinging the pickaxe pulled on different muscles from the digging and he had to take frequent rests. Sitting on top of the wall, he looked down on the little bay below him. It was more like the imprint of an index finger than a sweeping cove. All down the coastline there were inlets and bays like this, where the ocean had probed for weakness in the land. Barely two miles south-west of here, it had penetrated, carving a sea loch deep into the core of the island. Its name, like so many on the island, came from the Vikings of the Norwegian fiords. Masters of the sea, they had understood its importance for shelter and settlement. As had others before them, peoples lost in the mists of history. Their Neolithic structures of worship were beyond modern understanding, but it was clear what would have drawn them here: protection from the howl of the merciless Atlantic. That recognition linked Iain’s people to prehistoric man.

Beyond the sealoch, on its far shores, he could see the ocean break onto deserted golden sands. A flock of seabirds circled and soared around the scatter of large rocks that stood as defiant islets against the spread of the sea. The same scenes had played before the eyes of ages.

In the mid-nineteenth century when this house was first built, there would have been small boats on the shingle, beyond the tug of the tide. Ships of crafted wood and billowing sail would have been sighted out beyond the inshore currents. If his imagination ran deep, Iain could see his great-grandmother spinning at the doorway and her husband repairing fishing nets spread over the fence. The scene before him had such a timeless quality, yet only fifty yards up the road the modern world made its bold mark through the television aerials and steel cars.

Iain climbed down off the wall and resumed his task. Pebbles brought from the shore formed the hardcore of the floor. It would all have to come out. He had started breaking through at the gable end. From there, the floor sloped gently downwards, giving him a relatively flat surface over which to roll his barrow. Livestock would have been kept in the byre at the bottom end of the house and the slope was intended to ensure that their waste ran away from the living quarters.

On the wall at right angles to the gable end, near to the chimney, there was a cavity that would once have held a small wooden box containing his great-grandfather’s Bible and spectacles. Iain had begun digging where his chair would have been and where, nightly, he would have read from the Good Book. The old man’s wife would have sat opposite him.

As Iain worked his way across the opening of the fireplace, the sun began to sink towards the horizon. In gathering shadow, he deposited a last scoop of rubble into the barrow. It had been a long day, but a satisfying one. Leaning on the spade, he looked over the wall towards the setting sun. Then, as he turned to throw the spade on top of the barrow, something caught his eye. A fragment of cloth. His curiosity roused, he tugged at it, but couldn’t release it any further. It was stuck fast in the earth. Discoloured and dirt-stained, the cloth appeared to be plain, without pattern or embroidery. More than likely it was nothing significant, but Iain knew that it would scratch at his mind through the night if he left it now. It shouldn’t take too long to free. He dug away a bit more, pulled at the cloth and then dug again.

He couldn’t imagine anything of value being buried here; it was unlikely even to be of interest. But Iain was so involved in the house now, that his imagination was constantly encouraged to life.

Soon, the sun had gone completely and the gloomy half-light of dusk was creeping around him. He scraped away at the clay, exposing more of the cloth as he worked. Some rocks appeared to have been used to weigh it down and he began to sense that it really was something significant.

More than an hour had passed by the time he had exposed the entire length of the sheet. Parts of it had rotted away and he had inadvertently torn it in places, but he still couldn’t make out what was beneath. All he could tell was that parts of the bundle seemed to be long and hard.

He was excited. Could it be weapons of some sort? Weapons, rifles and swords, had been hidden in the thatch of the houses in the wake of the 1745 Rebellion, but that was long before the foundations of this house had been laid. Perhaps it might be guns brought home from the Napoleonic wars, or the Indian Wars of the American Prairies, or even souvenirs from Flanders trenches. Men from this village had fought in them all.

If his guess was right, there might be something of value here.

He lifted off one of the rocks at the end of the sheet and slowly peeled back the top layer. Clumps of dirt clung to it, adding to its weight. Nothing was revealed but more sheeting, which had been rolled over and over a number of times. He would either have to lift it out and unravel it all, or cut through it.

He remembered there was a combination knife in the car. The exhaustion in his muscles made him think about leaving it until the morning, but curiosity pushed him on.

As the village road meandered down towards the shoreline, the tar surface gave way to an overgrown, stony track just as it began the final incline, about a hundred yards from the foreshore. Iain had parked his car at the end of the surfaced road because he always enjoyed walking down that last stretch, watching the bay spread out gradually before him.