9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

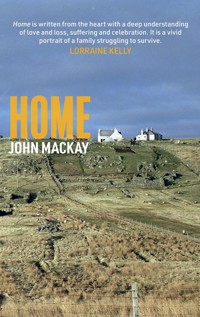

Built for the new age, the house stood boldly upright on the edge of the ocean withstanding the harsh blasts of a cruel century, nurturing and protecting the family within, watchful of hearts swollen or broken, dreams delivered and dashed. It had absorbed the tears and echoed the laughter. A sweeping saga of one family through a momentous century. Different people, divergent lives and distinctive stories. Bound together by the place they called home. But one of them is missing, lost to the world. An unknown grandchild, born to a son who went to war and never came back. As the years pass, through wars and emigration, social transformation and generational change, the search continues. And the questions remain the same: who is he? Where is he? Will he ever come home?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 444

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

JOHN MACKAY’s Hebridean roots stretch back beyond written records. His first three novels, The Road Dance, Heartland and Last of the Line, all draw on that heritage and were Scottish bestsellers. Home is his fourth novel. He has made appearances at the Edinburgh Fringe, Aye Write and Celtic Connections, and his writing has featured on national television, radio and press. A movie adaptation of The Road Dance was recently filmed on the Western Isles and will be premiered soon. He is the co-anchor of STV’s News at Six and Scotland Tonight, the country’s most popular news and current affairs programmes. His experiences at the forefront of coverage of most of the major stories in Scotland in recent times are detailed in his book Notes of a Newsman, also published by Luath Press.

Praise for Home:

Home is written from the heart with a deep understanding of love and loss, suffering and celebration. It is a vivid portrait of a family struggling to survive. I read it in one sitting and I’m already looking forward to John’s next book. LORRAINE KELLY

Home is an epic tale – a magnificent Hebridean opus that takes one family on a fast-tracked journey through the arc of history, as the 20th century and world events impact on the old order. We witness the Hebrides at its time of greatest change and this story will resonate with any Hebridean home and family of the era. The ubiquitous themes of emigration, war, loss, joy and sorrow are all here in the timeless cycle of generations. John MacKay is an astute and empathetic observer of the Hebridean psyche, with a remarkable command of historical detail. CALUM MACDONALD, Runrig

By the same author:

The Road Dance, Luath Press, 2002

Heartland, Luath Press, 2004

Last of the Line, Luath Press, 2006

Notes of a Newsman, Luath Press, 2015

First published 2021

eISBN: 978-1-910022-68-9

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon byMain Point Books, Edinburgh

© John MacKay 2021

To those who knew No. 25 as home

Contents

Acknowledgements

prologue Different Days

Chapter One The Letter

Chapter Two Departures

Chapter Three The Boys

Chapter Four Telegrams

Chapter Five Homecomings

Chapter Six Revelation

Chapter Seven Dancing on the Pier

Chapter Eight New Blood

Chapter Nine A Task

Chapter Ten Witness

Chapter Eleven Gone from Sight

Chapter Twelve The Diminishing

Chapter Thirteen A Keen Mind

Chapter Fourteen The Storm

Chapter Fifteen A Discovery

Chapter Sixteen Changing Times

Chapter Seventeen History Repeated

Chapter Eighteen The Test

Chapter Nineteen Magan

Chapter Twenty The Visitor

Chapter Twenty-One New Lives

Chapter Twenty-Two Electricity

Chapter Twenty-Three A Return

Chapter Twenty-Four One for the Pot

Chapter Twenty-Five Changes

Chapter Twenty-Six A New Age

Chapter Twenty-Seven Visions

Chapter Twenty-Eight Prodigal Son

Chapter Twenty-Nine The Row

Chapter Thirty Conversion

Chapter Thirty-One Resurrection

Chapter Thirty-Two A Plan

Chapter Thirty-Three Mary

Chapter Thirty-Four A New Generation

Chapter Thirty-Five Fading Away

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Remembering Chrissie, Donald Murdo, Cathie, Joey, Sandra andlittle Mary IsabellaLove to Katie and InaMy sons Kenny & RossSpecial thanks to Laura TrimbleAnd to Lorraine Kelly and Calum MacdonaldAlso, Mairi MacIver, Margaret Ann Laing & Donnie MacintoshAli Cairney for the graphicsThe team at Luath Press

Welcome to Mairi MacKay – the new generation

And Joyce for everything, always

PROLOGUE

Different Days

NO ONE CALLED Angus MacLeod by his actual name. To all he was Faroe, on account of a cloudy story of landing on the North Atlantic archipelago during a youthful sailing adventure.

That had been a lifetime before. Now, his adventures behind him, Faroe was at home, looking at all before him and seeing that it was good. This was as complete as happiness could be. Nothing was forever. He had lived and endured enough to know that sorrow and joy followed each other as night and day, oftentimes straying one into the other. He knew to enjoy this moment, unsullied with thoughts of what else there might be or might have been.

Gathered around the table before him in the warm summer sunshine were his family, entire and joyful. They were the future and he now believed that future had been secured for them. Wherever they may go, wherever life may take them, they had this place as their home.

Having the right to such a place had been the culmination of a struggle through generations. And this home was fit for the new century: stone-built, slate-roofed, rising one-and-a half floors with dormer windows overlooking all before. If the old blackhouse had hunched to the ground for protection, the adjoining new one stood boldly upright facing forward to the changing times.

It was the nature of his people to think often of times gone before. Faroe could enjoy the old stories and traditions, but he never let them bind him. He was conscious of the world around him and the rapid changes wrought by the first decade of the new century. The new house was his legacy to the future he saw for his own.

The tables, covered in white cloth, were laden with all that was good from the earth and the sea around them.

Faroe stood at the head of it, removed his cap and bowed. His iron grey hair, still thick, ruffled in the breeze. His face, cooked and carved by sun and sea, could have been older than his fifty plus years, but not younger. He heard without seeing, the silence falling around him as the chatter and banter petered out and his toddler grandchild was called to her parents’ side.

When all but the wind was silent, he began in a soft murmur.

‘Oh Lord, we are gathered here to give thanks to Thy goodness and mercy.’

Everything that was good in his life, his sons and daughters, his granddaughters, the new house, the food on the table, all of it was provided by the good Grace of the Lord. And all that had been sorrowful, the loss, the hunger, the tragedy, that too had been the Will of God. It was beyond man to understand the ways of the Lord, but the certainty of a greater purpose was as essential to his being as breath and blood.

Faroe had wanted to celebrate the new house as a symbol of better times, to bring the family all together and bond in the warmth of shared blood. And though he felt joy at having them around him, there was an indefinable heaviness in his heart, too. For Faroe sensed that this would be the last time they would ever be together again.

CHAPTER ONE

The Letter

MOR MACLEOD HAD matured without ever blossoming. She recognised her plainness and accepted it. As a younger girl there had been pangs of disappointment when a dress reflected in the mirror did not make her look as she’d imagined. But she had never been self-pitying and made the most of the qualities she did possess: her health and strength, her capacity for hard work and resourcefulness.

She only used to be conscious of it at the ceilidhs. The boys she knew in the village would dance with her and it would be fun, but how she would have liked to have known the thrill of dancing with someone special.

There were times, too, when the words of a love song would touch her so and make the tears spring to her eyes, but she would reproach herself for her foolishness.

In some ways, it was for the best. Being attractive got in the way. Mor had followed the fishing fleet over to the east coast, travelling as far as the south of England. For the comely girls there were the constant dramas over exchanged glances or kisses stolen before returning to the lodgings.

Mor could get on with what she was doing, working and earning money for herself and the family, without distraction. At twenty-one, she was one of the finest herring gutters and her team was always among the most productive. There was more satisfaction to be had from that than having a boy smile at you. She convinced herself of that anyway, but in truth she didn’t know.

She was loved, she knew that. The certainty of familial love was sustaining, but it couldn’t always be so. Mor wanted to be a mother and for that she would need to have a man. She had never tormented herself over having a man of her dreams, one who was honest and a worker would be good enough. But time was passing and opportunity with it. Day by day there was a subconscious acceptance that this was to be her life forever. Then the letter had come and everything changed.

It had been addressed to her father and he had placed it on the dresser behind the decorative plates she had brought home from her travels south. This had come from even farther away, from Canada, the Cold Country. Letters from across the Atlantic were a regular occurrence, but the reaction to this one had been different. Instead of an open declaration of news from family afar, her father and mother had a hushed conversation. While the family busied themselves with their own affairs, only Mor seemed to sense that there was something significant being hidden. It didn’t remain so for long.

With little privacy to be found in and around the house, her father had summoned her to join him on a walk down the croft. When they were some distance away from the others, he stopped, withdrew the letter from his pocket and handed it to her.

‘I’ve received this from my brother in Manitoba.’

‘Oh? Is Uncle well?’

‘It concerns you,’ said Faroe, ignoring her question.

Mor read it as her father stared beyond her to the sea. The letter spelt out a future for Mor which she had never considered. The man who owned the neighbouring farm to her uncle on the plains was also an emigrant from the village. His name was Peter and her uncle held him in great regard.

‘Peter,’ the flourishing, thick-inked English script stated boldly, ‘is a man of great endeavour and has established a holding of considerable size. It is his desire that he should find a companion to share his life, but in the vastness of this country that is not easy to accomplish. It is a position that might suit your own dear daughter Mary. I know from your letters that she is a woman of great capacity. She would be a fine match for this good man. I can testify myself that Peter is of upstanding Christian virtue. Dear Brother, I know it would pain you to have her travel so far from home, but there is a good life to be made here.’

Her uncle asked her father to consider the proposal and, if he saw fit, to seek Mor’s approval.

Mor dropped her hands still holding the letter and resumed walking. Faroe fell into step beside her.

‘Your mother didn’t want you to see it.’

They walked on for a few more paces, the silence disturbed only by the sound of the grass sweeping against her skirt and the ocean’s hiss. Faroe’s voice was less certain when he spoke again.

‘I didn’t think it right to hide it from you.’

‘Do you want me to go?’ Mor asked.

‘I don’t, my dear, but if it’s the chance of a better life, then who would I be to deny you? And if it’s the Lord’s Will, he will guide you.’

‘You would have me leave and never come back?’

‘I’d have you stay. I’d have you stay and never leave us. But one day your mother and I’ll be gone. We’ll have left you.’

‘You think I’ll be on my own?’

‘All I think is that you must decide. Only you.’

Mor’s mind had been in turmoil ever since. In one sense Canada did not seem so far away. She was not unfamiliar with the place names of Montreal, Toronto, Cape Breton and Manitoba. When letters came from family across the sea, her father would talk of these places as if they were neighbouring villages, although he had never been and would never go.

She knew that to go would be to never return. Her father’s dearly loved brother, the writer of the letter, had left a lifetime before as a young man and had never come back to his native land.

Everything she knew, the people she loved, the scenes and smells of her life would all be left behind forever. All to commit herself to a man she had never met and a country and way of life that was alien.

‘Why would I do that?’ she asked herself.

It was the obvious question, but something in Mor wouldn’t let her settle on the easy answer.

‘Whoever heard of such a thing?’ her mother had demanded. ‘People going off to marry someone they’ve never met.’

‘Now,’ her husband had chided her, ‘you know very well that it’s happened before, and in your own family too.’

‘Surely you’re not saying she should go?’

‘I’m saying neither one thing nor the other.’

‘You would let your own daughter go away on her own?’

‘She does every year anyway,’ Faroe said, defensively.

‘The fishing is different,’ his wife snapped back. ‘She’s with girls she knows and she comes home at the end of the season. But this…’

‘Now come, Chrissie, she may not go, but it has to be her own choosing.’

‘You’re her father,’ his wife said. ‘She will do as you say.’

Mor sat on the bench against the wall as her parents talked of her future across the open fire as if without mind of her being there.

‘Why did you let her see the letter anyway?’ her mother continued. ‘And what was your brother thinking of when he sent it?’

‘How could I not have let the girl see it?’

‘There are plenty others who wouldn’t.’

‘God will guide us. This is His Will and it may be the path that will bring her happiness.’

‘What happiness? Alone in a foreign land with a man she’s never met? All alone.’

The thought of her daughter’s solitude overcame her mother. Mor stood to comfort her and rested her hands on her shoulders. Chrissie patted her daughter’s hand rapidly and rocked gently on her stool.

‘Oh, my dear. There’s no ceilidh on the prairie.’

Later, Mor talked again with her father. She’d added more peat to the fire and it dulled the flames for a short time.

‘Do you think I should go, Father? Tell me.’

Faroe pulled at his grey beard and looked at the flames beginning to curl their way around the new peat. The fire sparked in the silence.

‘You heard your mother. We don’t want to you to leave. But I don’t know that you’re so sure. If you were, we would not be talking like this.’

Mor considered the shrewdness of what he said. If she had not thought of leaving, the letter would have been thrown in the fire already. Her father pared some tobacco from his pouch and began slowly and firmly packing it into his clay pipe with his thumb and forefinger.

‘What is he like, this Peter? What sort of man is he?’

‘Your uncle speaks highly of him. An honest man. Hard-working.’

‘Do you remember him when he was at home?’

Her father nodded slightly.

‘Tell me what you remember.’ Mor eased forward on her stool, leaning towards her father.

‘I don’t remember him so well. He was young when he left.’ Faroe spoke in hesitant sentences as he tried to recall. ‘Quiet, he was quiet. Not one to draw attention to himself. He came from a God-fearing family, that I do know. They were good people.’

‘But what was he like?’ pressed Mor. ‘What did he look like?’

‘Oh, now you’re asking,’ sighed her father.

Mor rocked back on the stool in exasperation and saw a smile spread beneath her father’s whiskers.

‘Oh, Father!’ she exclaimed, aiming a playful slap at his arm.

‘He was like his people. Very dark. A tall lad. Strong. Now, was he handsome?’ he smiled gently at his daughter. ‘Well, I’m not the one to know that.’

Mor listened intently to his every word, trying to create a picture of this man. She knew his brother was one of the villagers, but now she tried to call to mind every detail of him. There wasn’t much that had registered.

‘I tell you what I do know,’ continued her father, ‘although the boy was gone at the time, your mother knows more about this than me, there was a girl, from Siabost, I think. She died young. She was grown up, but younger than you are now. It was very sad. The consumption. Now, I’ve heard they’d been engaged, her and this boy Peter, and she was to join him in Canada. Well, of course, that never happened.’

Mor thought of the young man leaving home to make a new life for himself and his betrothed, only to be left alone in a foreign land, grieving for the loss of his love. She felt a deep empathy for him and it confused her. How could she care for a man she had never met? Yet, this man had asked for her from far across the sea. Who was he?

Her father’s voice drew her eyes to him again.

‘The life ahead of you here will be hard. We have to work for what the Lord provides. The work will be no less hard over there, but maybe there are greater rewards to be had.’

He sucked on his pipe and Mor heard her mother call her name. As she brushed past him, his teeth bit down harder on the pipe stem.

CHAPTER TWO

Departures

‘WILL YOU BE making the fishing of it this year, or will the Bugachd have grabbed you by then?’ teased Murdo.

‘Will you stop such talk?’ Mor reprimanded him. ‘Keep your city filth where it belongs.’

‘Ah Mor! What have I said that was wrong? Maybe if you let big Bugachd in the road give you a squeeze, you would understand.’

Mor hit him on the shoulder in exasperation. He laughed, caught her in a bear hug and tried to dance with her, his blue eyes sparkling and a lock of fair hair falling over his forehead. She began laughing, despite herself and they embraced affectionately.

Murdo pulled on his coat and slapped his bunnet onto his head. His brown, cardboard suitcase lay at his feet.

He had been working his way through the assembled family, shaking hands, tousling hair, throwing dummy punches at his younger brothers and hugging his sisters. Faroe shook his hand tightly.

‘Take care of yourself, Son, and try to write a letter sometime.’

‘I will, Father, I will.’ He meant it, but neither believed it would happen.

He came to his mother last as she stood quietly. He was serious for a moment, stooping to hold her tightly and whispering quietly that he loved her and would be back again soon. Then he leaned over to grab his case and when he stood upright the smile and laughter were back.

‘Right! Make sure this new house is still standing when I get back. A man from the big city expects a certain style, you know.’

The home had been a quieter place when Murdo first left two years previously to seek work in the booming shipyards of the River Clyde. He could have stayed on the croft, but nothing could change the fact that Lewis was the eldest son and Murdo would never be more than his brother’s tenant. The quieter, steadier ways of his father and brother were always going to be too stifling for Murdo and he followed the way of most younger brothers. It was not a source of resentment, rather an acceptance of his place.

He picked up his case and set off down the road, the cries of goodbye sending him on his way. His mother turned back to the old house to busy herself to distraction.

Mor watched her younger brother until he was out of sight and wondered whether she would ever see him again.

‘How romantic!’ Mor’s friend Effie clasped her hand to her breast.

‘Eesht, Effie!’ Her other closest friend, Mairead, waved her hand dismissively. ‘She’s never met the man. How can she marry a man she’s never known?’

The three girls had grown up together, shared each other’s lives and now formed one of the best gutting teams following the herring. They were in town for the summer catch. Effie and Mairead would slice the belly of the fish and remove the guts, throwing the carcass to the side in order of size. Being taller Mor was the packer, placing the gutted fish into barrels with salt until they were full. It was hard work, but they were fast, the two girls’ gutting knives working in a blur and Mor not missing a beat with her packing.

‘You can’t,’ insisted Mairead. ‘You don’t know what’s waiting for you over there. You know nothing about him. He might be some old man who’s lost his mind.’

‘He’s not that. I know he’s not that,’ said Mor, feeling the ache in her back as she crammed the fish into the bottom of a new barrel.

‘He’s over there all on his own. He just needs a woman to love him,’ said Effie.

‘Would you listen to this one?’ said Mairead, gesturing with her head. ‘As if she would ever do the same herself.’

Mor removed her head from the barrel.

‘Can you imagine marrying his brother, Coinneach?’ continued Mairead. ‘He’ll be an even older version of Peter’

‘Oh, Coinneach’s alright. He’s got nice blue eyes,’ gushed Effie.

‘Is there any man you don’t find attractive? Honestly, I don’t know how you’ll ever stay married. You’ll be chasing after all of them.’

‘I won’t,’ protested Effie, blushing. ‘I’m just saying he doesn’t look so bad.’

‘He’s old enough to be your father. Have you no shame?’

‘Just because you’ve got your Tormod, doesn’t mean other men can’t be looked at.’

‘Not when they’re married, no. What’s the point?’

‘She’s always so cheerful,’ interjected Mor.

Her two friends were momentarily confused that their heated discussion had suddenly gone off at a tangent.

‘Who? Who’s cheerful?’ asked Mairead, her hands still automatically gutting the fish.

‘Coinneach’s wife. She’s always smiling. They must be very happy.’

‘What’s that got to do with anything? So Ciortsadh is a cheerful woman. We all know that. But she’s not the one you’d be marrying.’

Effie giggled.

‘It’s not even her husband you’d be marrying,’ Mairead went on. ‘It’s his older brother who nobody’s seen for twenty years.’

‘Oh, the poor man,’ sighed Effie, shaking her head.

‘Poor woman who meets him, I’d say. Twenty years on a farm with no company. He’ll be bursting.’

‘Oh Mairead, you’re terrible,’ squealed Effie in a peal of laughter.

Mor wasn’t laughing.

‘Oh, come on, Mor, you’re not really thinking of going,’ challenged Mairead.

‘No, I don’t suppose I am, but…’

‘What’s the but? An old man far from home. What is there to think about?’

‘He’s not an old man,’ repeated Mor emphatically.

‘Mor, you can’t.’

‘I’m not saying I am.’

‘But you’re not saying you’re not.’

‘This man has asked for me, that’s all. No man has ever asked for me before.’

‘Nonsense,’ spluttered Mairead. ‘You’re hard on yourself. Who knows what will happen in time?’

‘If I went to any of these men on the pier right now…’ began Effie.

‘Don’t do that, whatever you do, don’t do that,’ interrupted Mairead. ‘These dogs would be over here in the shake of a tail.’

Mor giggled.

‘Would you look at that laugh? Enough to lift any man.’

‘Oh, stop it, Mairead!’ Mor waved her hand at her.

The three fisher girls laughed hard together as they had done so often before.

‘Oh,’ gasped Effie. ‘I would miss this if you left.’

Mor knew that things would change anyway whether she stayed or went. Mairead was to marry when the season was over and Effie would do the same before long. She was the only one without that certainty. Maybe this was her chance, maybe the only chance she would ever have.

The time was fast approaching when Mor would have to decide. The call would come soon for the herring girls to head off to the east. If she began that cycle again, the chance may be gone.

The long hours of gutting and packing the fish would become part of her past if she left. After she’d sailed the ocean and stepped off the boat on the other side, she would turn her back on the sea and travel into the Canadian interior. She would never see the sea again. That much she knew from her uncle’s letters.

Life without the sea was beyond her imagination. The ocean was as essential to her existence as the air she breathed and the land she walked. It had sculpted her island and shaped her people.

The separation from the rest of the country, from the rest of the world, made their island distinct and unique. Many enjoyed the life, but others found it oppressive and sought the opportunities offered by sailing away.

However one viewed it, as a life support or spirit draining, the sea was constant. In natural harmony with the wind, it set the mood of each day, sighing contentedly in the sunshine or thrashing in the gales.

What would it be like to live on flat, endless plains, where the clouds that spread had already passed countless homesteads, and where, without a contoured landscape, the winds could gather force unhindered?

Mor knew that she was adaptable, she had proven it all her life, taking to each new task with verve. Intimidating though the thought of being so far from home was, she had no doubt she could overcome it and make a new life for herself. What she was not so certain of was how she would cope away from her family and with the man to whom she might be committing her life.

That was why she found herself at Peter’s brother’s door at the end of a long day. Neither he nor his wife seemed surprised to see her and she had been made to feel welcome with tea and scones warm from the griddle. While Coinneach remained quiet sitting against the wall, his wife, Ciorstadh was more forthcoming.

‘We thought you might come.’

‘Peter has been away a long time,’ Ciorstadh had begun, after settling herself onto a stool opposite Mor. ‘It was twenty years ago, just after we married. He heard about Canada and the talk of land to be had in Manitoba. Well, he decided that’s where he had to go. Oh, but it broke their mother’s heart. Do you remember, Coinneach, her sitting there where you are now?’

Her husband’s eyes remained fixed on the fire and Mor wasn’t sure if he’d moved his head.

‘The day he left, oh well…’ She shook her head and sighed.

Mor sipped some tea, strong and sweet.

‘He got himself a farm—’ Ciorstadh picked up again.

‘Five hundred acres now,’ came a deep, mumbled interruption from Coinneach.

‘Yes dear,’ continued Ciorstadh, unfazed. ‘But he started with nothing. Just a bit of land from the government. He’s got hired helps now.’

‘Too much for one man,’ rumbled Coinneach.

There was a silence of unasked questions. It went on too long for Ciorstadh.

‘He needs a wife, Mor.’

Now that the discomfort had been overcome, the discussion began in earnest.

‘Why me?’ asked Mor. ‘He doesn’t know me.’

‘He knows of you. He knows your people.’

‘Yes, but he doesn’t know anything about me. And I know nothing of him.’

‘He does know about you. He’s asked.’

‘How did he know to ask about me, though? Why would he even have considered me?’

‘You’re from home.’

‘What of the Canadian girls?’

‘You would understand his ways. You’d even speak his language.’

‘There are other women in the village.’

‘He knows your uncle. Peter wrote to us asking us about you. He’s out there on the prairie and he doesn’t see many people. Your uncle is one of the few he knows, even after all that time. He’s like that one over there,’ Ciorstadh gestured to her husband, smiling. ‘Goodness knows how we got married. He wouldn’t talk to me.’

‘I didn’t get the chance,’ came back the retort.

‘Eesht! Peter wrote asking about someone keeping house for him. I’ve got the letter there in the dresser. Someone who might provide him with company.’

‘He never mentioned marriage?’ Mor was perplexed.

‘What else could he mean?’

It wasn’t quite as Mor had imagined it and Effie’s notions of romance were banished, but they had made little sense anyway.

‘This hasn’t been sudden, although I know it must seem like it to you.’

‘What about him? Tell me about him.’

‘Peter is a good soul, a good man. I have a photograph. Coinneach.’ It was an instruction to her husband, who opened a drawer in the dresser.

Mor saw movement at the doorway. The couple’s two youngest children were standing there, smiling. They were girls aged about ten and twelve. Mor knew them from the village and smiled back.

Coinneach moved across her view and gave the photograph to his wife. She glanced at it before handing it to Mor.

‘That’s him. That’s Peter, just before he left.’

The man posing stiffly in the photograph against a sturdy, ornate, wooden chair was tall and broad. His hair was parted in the centre, slicked down either side of his head and teased up into curls. His sideburns were long and bushy, but his face was clean shaven. His eyes, looking steadily off to the side of the camera, were deep set. The face was strong with prominent brows, cheeks and jaw.

‘Of course, he’ll have whiskers now.’ Ciorstadh waited eagerly for Mor’s reaction.

‘He’s a striking looking man,’ said Mor.

She made other complimentary observations, almost to please Ciorstadh. Not that she was unconvinced by what she was saying. The overriding impression was of strength, but she thought she could read kindness in the eyes.

‘You keep that until you know your mind on the matter,’ said Ciorstadh.

‘Tell me about the other girl,’ said Mor.

Ciorstadh and Coinneach exchanged glances.

‘It was very sad,’ sighed Ciorstadh. ‘When Peter was a young man, not that he’s old now, of course, but when he was young, Peter had, what you might call, an understanding with a girl over in Siabost. A bonny girl she was. Quiet, like himself. The idea was that he was going over to Canada and once he got himself some land and some money, she was to come over to join him. Well, it never happened. The poor girl took ill and she died. TB. Of course, Peter was over there on his own. It was their father who wrote to tell him and we never heard from him for a long time after that. It must have hit him hard. In all those years I have never known him to mention a woman in any of his letters. Mind you, he doesn’t say much at all.’

‘So, what’s changed?’

Ciorstadh shook her head questioningly.

‘Maybe he sees all that he has and wonders what it’s for.’

Coinneach stood up and strode out of the room, nodding to Mor as he went.

‘The cows,’ said Ciorstadh by way of explanation.

Mor walked slowly back through the village, the only home she had ever known. The sun had already fallen behind some clouds creeping in from the west. All the way out the road wound around houses preparing for night to fall, many of the occupants hailing her as she went. As she passed what was known as the Sisters’ House, she saw one of the spinster sisters bringing a pail of water from the well.

Three sisters lived there and kept their croft and livestock as well as any man, and better than most. They had always looked the same to Mor, seemingly middle-aged, their faces lined and weather beaten, their greying hair pulled tightly beneath their head scarves. They were hearty women, if a little rough at times, and Mor enjoyed their company. Their talk was always of the seasons and the work to be done on the croft. As a woman who thrived on hard work herself, Mor had admired their labour ethic and their independence.

Tonight, though, as she walked with thoughts in her mind, she saw the sister with the pail, bending nearly double and leaning her hand against the wall of the house for support.

Rising up the hill towards her own home, Mor looked about her, to the peat smoke rising from chimneys, to the darkened earth turned ready for the planting and the sombre dark mass of the sea beyond the hewn rocks of the coastal cliffs.

The houses were strung out all along the road right down to the shore. She knew everyone in these homes and a little about each of them. And they knew her. They knew her and her people, and her people’s people. It was a tight bond that provided warmth and protection, a connection that could only be experienced from belonging, from having been raised among them.

And yet, as she turned to face the new house that was the symbol of her family’s future, the image that stayed with Mor was that of the aged spinster struggling with the pail of water.

Three months later Mor stood at the door of the house, her kist packed and loaded onto the cart. She wore a long, dark coat and a navy straw hat that shadowed eyes, dark and red. Red from tears and dark from a night spent beside the fire with her mother.

They had talked and reminisced and cried through the small hours, Mor ignoring her mother’s repeated suggestions that she sleep to be fresh for the long journey ahead. It would have been impossible for either of them. Now the moment of the final goodbye was upon them. There were no words, just a hug that neither could bear to break.

The last Mor saw of her parents was her father waving his cap and her mother flapping her hand in the air.

The last they saw of their daughter was in the cart driven by her brother Lewis, waving and waving and waving.

Three miles further on, through a dip in the hills, she saw the distinctive dormer windows against the roof of the family home. Her eyes cast down as she thought of her mother returning to the fire in the old house and of her father looking forlornly for something to occupy himself.

When she looked up again, her home was gone from sight.

CHAPTER THREE

The Boys

THE HOUSE CAST a shadow over Fresh the postman as he pushed his bicycle away with one foot on the pedal and swung his other leg over onto the other. His name came from his daily salutation of ‘What’s fresh?’ to everyone he saw on his daily round as he sought their news. He whistled as he rolled back into the early morning sunshine, leaving much excitement behind him.

The letter was the addressed to Angus MacLeod and Lewis recognised the writing to be his sister’s.

‘Take this to Grampa,’ he instructed his daughter. She skipped away obediently down to the old house. Lewis reflected on how big Tina was becoming since his sister had last seen her. He followed her down to his parents’ home. The activity drew other members of the family in curiosity.

‘A letter from Mor,’ explained Lewis, over his shoulder.

She had written several over the past two and a half years, telling of her new life and seeking stories from home. It had become a ritual for the family to hear Faroe read aloud what she’d written and always with a wee mention of everyone.

Mor’s journey had been long and arduous, but exciting. She travelled to the River Clyde, regrettably not having had a chance to see her brother Murdo in Glasgow. From there she sailed to Canada, passing her home island on the horizon. She had presented that factually, but could not bring herself to describe the sorrow that had swelled within her as she saw the island of her birth slip away from sight, straining until the very last for a final glimpse until unsure whether it was waves or land. She had sobbed so sorely her eyes were still wet when she finally found succour in sleep. What she would have given for a boat to have been lowered and sailed home. It had been the lowest point of all and, although she still cried at the thought of home, she had taken strength from the fact that she had endured such despair.

Docking in Montreal, she had travelled by train into the interior. ‘It’s like nothing you can imagine,’ she’d written in her first letter. ‘I was on the train for more than a day and all I could see was farmland or forest.’

Peter had met her at the station and they had ridden on his cart back to his farm. It had been a little uncomfortable, she said, because he wasn’t a man for saying much, but he quickly proved to be kind and thoughtful to her. His farm was ten times the size of the croft and they grew mostly grain crops. The heat of the summer was unlike anything she’d ever known, ‘Not even a breeze off the sea.’ The winter was another revelation and they had to dig their way out of the house through the snow.

In time Mor had developed a deep fondness for this man. ‘I run the house,’ she wrote, ‘and he is content for me to organise it as I wish.’

They were married the following spring, with her uncle’s family in attendance. ‘I wore Auntie’s wedding dress. It was a wonderful day, but how I wish you all could have been here to see it.’

This latest letter carried a certain inevitability. Little Tina gave the letter to her grampa as he came out of the old house to see what the activity was. He asked her to fetch his glasses and she went into the blackhouse, as familiar there as she was in her own home, returning with his wire-rimmed spectacles. Her grandfather pulled them on as the family gathered round.

Faroe carefully opened the letter with his tobacco knife, held it at arm’s length and began to read aloud.

Mor asked after everyone and, as ever, for news from home.

Then, ‘I am happy to tell you, dearest Mother and Father, that you are grandparents again. I have been blessed with a healthy baby boy, born last week. He is to be called Peter after his father and Angus after yourself.’

The news was greeted with outbursts of happiness. Faroe continued to read through the letter, as Mor described who her new baby resembled. ‘Sometimes, despite myself, I see he has a look of Murdo. I don’t know how that can be.’

Her brother, home for a short holiday, smiled broadly, ‘He’s obviously a fine looking fellow.’

Their mother went into the house to pour some tea, her joy tempered by sadness. It was hard not to think of her own daughter so far from home with the grandchild she would never see. Faroe had followed her inside to the smoky atmosphere of the old house.

‘She and the baby are healthy, Chrissie, and we must be thankful for that,’ he said.

Soon the family all gathered, chattering excitedly about the news and Chrissie set her face to share in their pleasure.

‘We should be thankful he’s like me. If the baby has looked like them,’ continued Murdo, indicating teasingly to his younger brothers, ‘the Canadians would have packed him and his mother back on a boat home.’

It provoked the intended tirade of insults in retort.

‘I’m going to be married,’ Murdo had announced on his arrival. He had returned home on a short visit after his summer militia training.

‘Married?’ asked his mother, aghast.

‘That’s what I said.’

‘You could have told me.’

‘Isn’t that the very thing I’m doing now?’

‘Who is she?’

‘Her name’s Irene and she’s the prettiest thing in all of Glasgow. A face to ripen the barley. Look.’

He presented a photo from his wallet to his mother. The girl was small and pretty, her hair bobbed stylishly with curls.

‘We met at the dancing,’ Murdo continued as the photo was passed around for everyone to see.

‘When you’re away from the yards,’ said Murdo to his eager younger brothers, Donald and Alasdair, ‘the time’s your own and you’ve got money to spend. And there’s plenty to spend it on, let me tell you.’

The city, he told them, was more than they could ever imagine. So big and so many people.

‘And,’ he added with a big wink, ‘plenty of girls. Oh, plenty indeed. It’s hard work, but you’ve got to have some pleasures to make it worthwhile.’

His mother waved a hand dismissively at him.

‘Eesht. Don’t you be putting ideas in those boys’ heads. When are you getting married?’

‘Soon as I get back.’

‘Oh, my goodness!’ said Chrissie.

‘I’ll bring her home with me next time. You’ll like her, Ma.’

‘Will there be any of your own there?’

‘No. Just me and her. Get it done quick, I say.’

Despite pressing him, his mother could get no more information out of Murdo. It was Lewis who found time alone with him, late after everyone else had settled down for the evening. He saw his brother sitting on the wall at the back of the house and pulled himself up alongside him.

The relationship between the two had strengthened since Murdo’s departure. Now they saw each other for brief, intense periods when Murdo came home and he was away again before the friction of their differing personalities could generate any heat.

The sky was still pale and the moonlight splashed light on the ocean. Some stars were beginning to glimmer through.

‘Do you miss home at all?’

‘Sometimes. I miss this,’ said Murdo spreading his arms before him. ‘But I like the city. Can’t see me leaving there.’

There was a moment of uncomfortable silence as both anticipated the conversation to come.

‘So, she’s a nice girl,’ began Lewis tentatively.

‘She is.’

‘We’d no idea.’

‘About what?’

‘Your marriage. You never said.’

‘I’m not great for writing, you know that.’

‘No, but you might have told Mam.’

‘Why should I?’

‘You know why.’

‘I’m telling you all now.’

‘Yes, but it’s all…’ Lewis searched for an appropriate word. ‘Sudden.’

‘I knew she was the one for me. Why wait?’

‘That’s all it is?’

‘Yes, that’s all it is.’

Lewis was in no mind to push the issue. Murdo was never one for talking deeply and was not going to reveal anything he didn’t want to. For his part, Lewis was content not to know.

The dark head and eyes of their younger brother Donald emerged from the shadows settling on the land. A weighted sack over his shoulder was evidence of another fishing trip to the cliffs. Donald lived his life out of the focus and fuss of his parents. His stillness allowed him to go unnoticed for hours. That suited him fine.

‘You made barely a sound when you came into this world my dear,’ his mother would observe as she held him to her as child, ‘and we’ve scarce heard you since.’

Dropping the sack and a rod onto the grass, he pulled himself onto the wall beside his brothers, his wellingtons rubbing against the stone.

‘Looks like a good catch,’ said Murdo.

‘Aye,’ said Donald.

‘There might be no marriage,’ continued Lewis. ‘Some of the boys were over in town and they’re saying the Kaiser and the Czar are fighting now. There’s a lot of talk of war.’

‘That’s all it is, talk. Everyone was on about it at militia camp. I don’t see it myself.’

‘You’d have to go if it was, wouldn’t you?’

‘So would he,’ Murdo gestured with his thumb to his younger brother.

Donald had been in the Royal Naval Reserve this past year. It was the wanderlust that drew him, not the money. All his life he had watched the ships on the horizon. From where had they come and to where were they bound?

‘They count on you going,’ continued Murdo. ‘Take the money from the militia and you have to go if they come calling. It won’t come to it.’

‘You seem very sure,’ said Lewis.

‘And I’ll tell you why. Money. It’s different out there,’ he gestured eastwards in the vague direction of the mainland. ‘Money, that’s all they care about. Some of the wealth I’ve seen in Glasgow. It’s hard to imagine from up here.’

‘There’s people who will make money from war.’

‘Maybe, but more will lose. So, if there is a war it’ll be short. Too much money to be lost.’

‘I’m not so sure,’ said Donald thoughtfully, making his first contribution to the discussion.

‘What are you hearing?’

‘That the Germans have built up their Navy. We’re doing the same, I know that’s true.’

‘It’s all for show. It’s brinkmanship. Who’s going to fight over the killing of some foreign prince? It’d be madness.’

‘They’ve started already,’ said Lewis sombrely.

‘Even if there is a war,’ Murdo continued, ‘it’ll last a couple of months and then it’ll all be sorted. Might make us some money, eh?’

The three brothers sat awhile, enjoying the closeness of blood on blood. Above them was the timeless sky and beyond them the certainty of the tidal sea. All around them the night was peaceful and warm.

‘It’s nearly the Sabbath,’ said Lewis, checking his fob watch. ‘We’d better turn in.’

The mobilisation order for the Naval Reserve was read out in church that morning.

‘There is darkness around us,’ said the minister. ‘The call has gone forth and our young men of the sea must respond. They will do their duty for King and for Country. It is for freedom they fight. And for God.’

His words stirred hearts and fear among the assembled congregation. The doubt was gone. The apprehension of uncertainty was banished. Everyone knew what was to come and it thrilled and it scared. The young men glanced at each other with fervour in their eyes. The fears were their mothers’.

Outside their enthusiasm burst forth and they dashed around, clapping shoulders and hitting each other with their caps. Their exuberance contrasted starkly with the older folk. As the boys of the Naval Reserve made quickly for home, their mothers walked slowly as if to hold back time and delay the inevitable parting.

‘What does it mean for you?’ Faroe asked Murdo.

‘I don’t know for sure. There’s a lot more has to happen first. No one said that we were at war yet.’ He did not seem reassured by what he said himself.

‘They’re saying you Army boys will get your letters this week,’ said Donald.

‘What letters?’ asked his mother.

‘Mobilisation, Mam.’

‘Letters telling them to go and fight. It might not happen,’ Faroe reassured her.

The youngest brother, sixteen-year-old Alasdair, did not sense the anxiety at the table, nor could he contain his own excitement.

‘Do you think I could join up? What do you think?’

‘Aye,’ said Murdo, attempting to make light of his own concerns. ‘You head off to town and tell them you want to fight the Germans.’

‘You really think so?’

‘Don’t be so daft. You’re still a boy.’ reprimanded his father.

‘I am not,’ protested Alasdair.

‘How many of my children do they need?’ asked Chrissie, her voice betraying anger.

‘Listen, Mam,’ said Murdo, ‘even if they call us, it’ll all be over before we’ve finished the training. They’ve got the regular soldiers if they need them.’

‘Then why call for you at all?’ asked his mother. ‘Wasn’t my own grandfather made lame by Napoleon? And your cousin lying over there in Africa, killed by the Boers. You go to anywhere in the world where the Army has fought and you’ll find boys from this village among the dead. They always need more.’

That night in the old house, Chrissie couldn’t go to her bed. She sat brooding by the light of the lamp and the dying fire, her shawl wrapped around her. She had seen it before, the euphoria of invincible young men off to do battle. It was closer to her now than it had ever been. Now it was her own sons. They would be different when they came back, no matter what, innocence lost. Perhaps Murdo, with his bravado and experience of the wider world might cope, but Donald was a quiet soul, at peace with the natural world around him. What might the horrors of war do to him? She was losing her son that night in one way or the other, of that much she was certain. God willing, that would be the worst of it. They might not come back at all.

Few slept in the new house either. In their bedroom upstairs, Murdo and Donald talked of going to war, the moonlight casting their faces in a pale glow. Donald moved constantly beside his brother in the bed. Murdo lay on his back, his mind too unsettled to allow sleep.

‘The boys are all saying it’ll be over before it starts,’ said Donald. ‘D’you think we will see any fighting?’

‘I don’t know about you Navy boys, but I think the Army will.’

‘The Germans have got a big Navy.’

‘And that’s why they need to be stopped.’

The youngest brother Alasdair, pulled himself up in the bed next to them, resting the side of his head on his hand. His brothers’ conversation on top of the excitement of the day was too much for him to sleep.

‘Why are we going to war, Murdo?’

‘It’s the Germans. They need to be stopped.’

‘What have they done?’

‘They’ve attacked Belgium. They’re killing people and raping the women.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘It’s bad.’

‘Can’t the Belgiums fight them?’

‘No.’

‘So, we’re fighting for them?’

‘That’s it.’

‘Why us?’

‘Because someone has to.’

‘But why us?’

‘It’s simple. Listen, if the King calls you to fight, then you go. He wouldn’t call you if he didn’t need you.’

‘Are you scared?’

‘No. Away being a soldier with your pals? I can’t wait.’

‘But you could get killed.’

‘I suppose, but… Och, that won’t happen.’

‘I wish I could go with you,’ said Alasdair longingly.

‘Do you think you’ll have to kill one of them?’

‘I suppose,’ Murdo replied uncertainly.

‘What would that be like?’ continued his brother.

‘You fire your rifle from so far away I don’t think you’d know. That’s what it’s like in training anyway.’

‘When Mam’s grandfather fought, they were still using swords and bayonets. It was man to man. Plunging a bayonet into a man’s guts and watching him die. Aaargh.’ Alasdair added the sound effects of imagined cries from dying soldiers.

‘Will you stop that?’ Murdo snapped.

Alasdair fell back onto his pillow, embarrassed and disappointed by his brother’s reprimand.

‘You don’t see them in the Navy,’ said Donald quietly.

‘Who?’ asked Murdo, still unsettled.

‘The enemy. These big guns, they can fire for miles. When we do the shooting practice, sometimes you can’t even see the target it’s so far away.’

‘Are the Germans the same?’ asked a cowed Alasdair.

‘I’m sure they will be.’

‘Does that mean they could fire at you without you even knowing?’

‘It must be so.’

‘You wouldn’t know what hit you?’

‘No. I don’t suppose we’d know what was coming.’

When the day came again, few in the house had slept at all. The relief of the morning was discharged in a bustle of activity, of preparing food and packing bags. It was the same throughout the village as the young men prepared to go off to war.

First was Donald. He emerged with his bag, packed by his mother during the sleepless hours, slung over his shoulder, a tweed jacket and his cap fixed at an angle on his head. The family gathered at the front of the house.

Lewis sat waiting on the gig, removed from the emotion at the door. The horse stood patiently, but for the occasional toss of its head.