Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

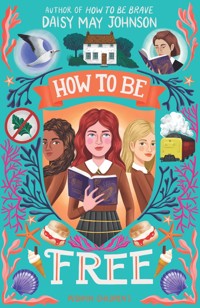

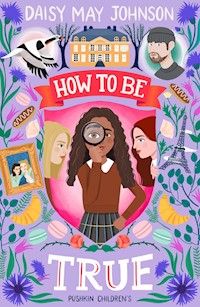

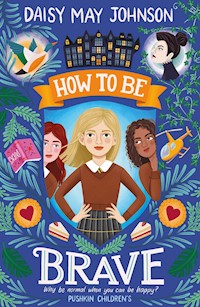

- Serie: How to Be

- Sprache: Englisch

It's the start of a new term at the School of the Good Sisters and Hanna, Edie and Calla are ready to enjoy everything their extraordinary school has to offer. But they soon realise that Something Is Most Definitely Up. Not only is a mean businessman trying to open a kale factory in Little Hampden and remove all their delicious snacks, but their beloved Headmistress Good Sister June has disappeared - and nobody knows where she's gone.It's time for Hanna and her friends to rally an army of first years to protest against the horrors of kale while they set out on an adventure to bring Good Sister June home. As they travel across the country following a trail of clues, they will learn about the power of family, friendship, and a well-timed slice of Victoria Sponge...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

5

“No girl is an island” —john donne

(Technically he said: “No man is an island”, but he is not here right now to correct me.)

6

CONTENTS

THE VERY BEGINNING

This book is about three things.

Finding things. In particular, it is about finding a nun who goes missing and the three small girls called Hanna Kowalczyk, Calla North and Edie Berger who set out to find her and bring her home.Family. A lot of people think that family is just the people that you are related to but it is so much more than that. Families can be made of the people you love, your pets, your friends, your favourite recipe for salted caramel truffles, and people that you’ve not even met yet.Footnotes. This is not just because I enjoy things that start with the letter F but rather because I am very forgetful and footnotes allow me to add things in when I remember them. These things might be Additional Important Information, or Jokes, or Useful Things That You Should Be Aware Of. All you need to do is look for the 8little number in a sentence (like this one1), and find the number at the bottom of the page that corresponds with it.But before all of that, it is about a girl called Sarah Bishop.

1 This is a footnote. You will see that it is the only footnote on this page and now, all you need to do is go back up and read the rest of the sentence on the page itself. I am aware that is a lot of information to take in so you are welcome to stop for a moment and have a biscuit before you do. I recommend a pink wafer.

A GIRL CALLED SARAH

There are several things that you need to know about Sarah Bishop and the first one is this: she was born in the last days of the First World War and so, for a long time, knew a world with no cake or sweets at all. This was because of a thing called rationing. Rationing was when the government gave people a booklet full of small coupons. These coupons could then be used to purchase things and make sure that everybody got everything they needed during the war. The only problem was that when those tickets were used up, people wouldn’t have any left until the next ones were given out.

It took two years after the war for rationing to end. Sarah was two when it did and she watched as all of her neighbours and the people in her town embraced the freedom of a life without coupons and restrictions. Her parents, however, did not. They had been so saddened and broken by the events of the war that they did not quite know what to do with themselves. They would spend days trying to figure out what to say to each other and their daughter and failing entirely at both. And so they lived a quiet and small and sad life where they slowly withdrew from the world and all of the wonders that it 10had to offer. They ate plain and simple food, and refused social invitations and, when their sadness grew almost too much for them to bear, they would not even leave the house for weeks.

But then, one day, Sarah Bishop realized that there was another way to live.

This was all due to the work of Angela Anderson, her next-door neighbour. Angela’s daughter was getting married and Angela had decided to bake a cake to celebrate the occasion. Angela was not a good baker and occasionally she was even catastrophic, but fortune had favoured her on this day and she had somehow managed to bake the sort of cake that you might find if you ever looked up the definition of “cake” in the dictionary. It was perfect. It was so perfect, in fact, that Angela had asked all of her neighbours to come around and witness it. She had rung the doorbell of old Miss O’Hara from Number 47, knocked on the door of Mr and Mrs Jacobson from Number 49, and even though she could not quite believe that she was doing it, she had invited around the strange and never seen out in public Mr and Mrs Bishop at Number 51.

Mrs Bishop had refused, of course. It was almost instinctive to her now. “I have to look after my daughter,” she said. “And cook the supper. Then there’s the cleaning. You know.”

“It’s eleven o’clock,” said Angela Anderson, with a force that surprised her. “There’s time for all of that yet. Come and look at my cake and have a cup of tea, and bring your daughter too.” 11

She had seen the daughter going back and forth to school. Always by herself. Always far too pale for comfort. Never with one of her parents at her side.

“I don’t know,” said Mrs Bishop.

“Come,” said Angela Anderson. “Please.”

And for some reason that she did not understand, Mrs Eileen Bishop did. She brought her husband, George, dressed in his suit and as formal as a man going to church, and her small and wide-eyed daughter, Sarah, and when they had all finished staring at the wonder of Angela’s perfect cake, the wide-eyed Sarah walked forward and calmly helped herself to a bite.

Sarah was punished, of course, but she did not care. And even when she did care about being confined to her room or fed meals even plainer and sadder than before, all that she had to do was remind herself of how that cake had tasted. She had never thought that something like it could exist in the world. She wanted to know everything about it. She wanted to understand it, completely, and she wanted to make her own.

And so, Sarah began to educate herself. She would visit the local library on her way home from school and when the librarian was looking the other way,1 Sarah would sneak out of the children’s section and into the adult room where the recipe books lived. They mentioned 12ingredients that she had never tasted and places she had never heard of and sometimes, late at night, she would dream about the time that she might be able to make them for the people that she loved. She was not quite sure who these people might be and where she might find them but she knew with a definitive and sharp sense of sadness that they would not be her parents.

It was during one of her library visits that Sarah met Mrs Weisenreider, an elderly refugee from Germany, who had come over to England after the war and now spent her days reading cookery books to remind herself of all that she had left behind. Mrs Weisenreider was the one who taught Sarah about Springerle cookies, which were tiny little patterned biscuits that had been made in her Swabian village in Germany ever since the fourteenth century, and one day she gave Sarah the mould to make her own.

It was also Mrs Weisenreider who introduced Sarah to the other widows. They had come from all over Europe, “for love,” said Mrs Van Dam, “for freedom,” said Mrs Gladstone, “and not for the food,” added Mrs Bertolini, as quick and as smooth as anything you’d see on the London stage. This always made the rest of them laugh and then Mrs Weisenreider would bustle the group out of the library and down towards the nearest café for a cup of tea and deeply inappropriate gossip. Sarah was always sent home for this part and so, the moment she was old enough, she got a job in the café so that she could gossip with them. 13

When Sarah was twenty-one, she was given the unexpected present of two new baby sisters named Georgia and Lily. One week after this, the Second World War began and with it came the death of her father. He had signed up with the navy in the first few weeks of fighting, unable to deal with the thought of this happening all over again and unable to let it happen without him being involved, and he had lost his life almost as quickly. And so when her friends were moving on to do war work and dig for victory, Sarah stayed with her mother to help her look after the twins and keep money, somehow, coming into their sad and broken house. She doubled her shifts at the café and when the air raids began, she started to work nights as well as an emergency telephonist.2

Somewhere, in the middle of all of this hustle and bustle, Sarah’s mother died.

And that meant that Sarah had to become both mother and father to the twins even though she was barely an adult herself.

The widows helped her, of course, for they knew about what had happened and they all loved Sarah very much at this point. Mrs Weisenreider took in their washing to do alongside her own and Mrs Van Dam made enormous amounts of nourishing soup for them all to eat together while Mrs Bertolini and Mrs Gladstone sat down and 14looked through all of the paperwork and bills that Sarah’s mother had been ignoring for so, so long. It was then that they realized that things were about to go very wrong for Sarah and so they began to plot.

Their plot involved the sending of many letters to all of their friends and relatives scattered across Europe, and long conversations with each other at the café, and for a few months, Sarah did not know anything about it. She spent her days with the twins, and the love and help of the widows kept the three of them safe. She would talk about what the future might hold and dream of a bakery that might be her very own. “But I have to forget that now,” she would say to whichever widow was sitting by her side, “I have the girls to look after and I’m the only person they’ve got.”

One day, when Lily and Georgia were busy playing hopscotch with each other on the street outside, and the widows had received the final pieces of information that they needed, they took Sarah to one side and began the process of telling her everything.

“Sarah, my dear, we have something to tell you,” said Mrs Weisenreider. “We all care for you so much and we love you as if you were our own family. And we know that your parents have not left you with enough money to live on. There are so many bills here and none of them have been paid for quite some time. Did your mother ever speak to you about money? Properly?”

“I thought we were managing with my extra shifts,” said Sarah. “I didn’t know things were bad.” 15

“They are not good,” said Mrs Weisenreider. “There are many bills that have not been paid and your father, before he died, took out a loan with the bank. That has not been paid back either.”

Mrs Van Dam nodded. “There is no way that your shifts will cover all of what is owed. We have spent weeks trying to make the numbers work, but they will not. There is just not enough money.”

“So we have been putting a plan together for you these past few weeks,” said Mrs Gladstone at her gentlest. “And if you would be happy to accept our help, then we will give it to you.”

“But you’ve already given me so much,” said Sarah. “How can I ask any more of you than that?”

“But so much is not enough,” replied Mrs Weisenreider. “Permit me to explain our idea to you.”

And so she did.

1 Librarians back then were very fond of rules and could often be a bit scary when they found people breaking them. Now, of course, they are some of the best people on the planet and you should always bring them cake to celebrate this.

2 This is a fancy word for somebody who answered the phone calls at the fire station after a raid and sent the fire fighters to where they were needed the most.

I’LL NEVER FORGET YOU

The plan was this: train tickets to Cornwall for Sarah, Lily and Georgia; the promise of an apprenticeship in a bakery run by Mrs Bertolini’s best friend’s great-niece by marriage; and enough money to get Sarah started in a brand-new life doing the things that she had always dreamt of. It was the greatest gift that the widows could have given her and when Sarah protested it, when she told them that it was too much, they told her that they loved her and that she had to go.

“You have a life beyond this house and it is waiting for you to live it,” said Mrs Van Dam in her quiet and gentle way, “and it is our joy to make it happen for you.”

When Sarah protested again, Mrs Van Dam patted her knee, and Mrs Gladstone took her hand and Mrs Bertolini took the other while Mrs Weisenreider told her to write.

“Not every day,” she said, “because you will not have time and we do not expect it of you. But when you can, please tell us how you are. Please remember us.”

“I’ll never forget you,” said Sarah, and she didn’t. She sent the first postcard from the bakery, the day after she had made panettone for the first time, her hands still aching from kneading the dough and her mind still full 17of its magic. She sent the others on a regular basis from that point on and the widows devoured each and every one of them. They learnt about how Georgia grew up into somebody who was clever and quick and about how she always asked Sarah questions that she never knew the answer to. They learnt about Lily and about how she was funny and stubborn and was always the first to be awake and the last to fall asleep. And they learnt about how Sarah was becoming the baker that she had always dreamt about being.

In turn, the widows sent Sarah postcards of their own. They told her all about the things that were happening in the local area and even though these were not often the most exciting or dramatic pieces of news, for Sarah they were perfect. She learnt about how the library had got new books, about a group of nuns who were setting up a convent just outside of the village, and about how to make the perfect sponge pudding even though rationing was back in effect and half of the ingredients were missing.

For a while, there was nothing but postcards flying back and forth and Georgia and Lily grew accustomed to trotting down to the post office with another one in their hands and returning with a fresh one for Sarah to read. Even Mrs Bertolini’s best friend’s great-niece by marriage had become interested and was starting to learn English as a result of them.1 And when the postcards started to bring bad news with them, when one of the widows died 18and then the other, she was the first to wrap her arms around Sarah and help her through it all.

The last widow was Mrs Weisenreider, and even though her handwriting grew increasingly wild and her spelling even wilder, she wrote postcards right up to the end. For a while, both Sarah and Mrs Bertolini’s best friend’s great-niece by marriage2 worried about why they might have stopped coming and then a letter arrived which explained it all. Mrs Weisenreider had died and left Sarah everything that she had.

And everything, along with all of the money that she had saved over the years, was just enough for Sarah to buy a small bakery of her very own.

“Where will you buy it?” asked Georgia.

And for the first time in her life, Sarah did not have to think about how to answer one of her sister’s questions.

“Home,” she said.

1 Her vocabulary was very good but rather cake specific.

2 Whose name was Giulia Ricci in real life but nobody used that, not even Giulia herself.

A CLOUD IN YOUR HANDS

Sarah and the twins, who were teenagers now and passionately devoted to the wellbeing of each other and their sister, left Cornwall in sunlight and returned to Little Hampden in rain. They bought a small bakery just down from where Sarah had met the widows for the first time and even though the library was now a shop and the café was now somebody’s house, Sarah felt her heart warm whenever she walked past them. It was because of this that she named the bakery Bishop & Family1 and every moment that she could, she told the twins about the widows and about how they had saved the three of them when everything had seemed so lost.2

The bakery opened on the first Monday of July. It was a good day to choose for this turned out to be the day after rationing officially ended again across the country and people could finally put their ration books aside and could go to the shops and buy what they wanted and without having to save their coupons up for weeks to 20afford it. The people of Little Hampden celebrated with a party that saw them dance from one side of the village to the other, pausing only to buy everything that Sarah had baked that morning, before they came back the day after and then every day after that to do it all over again.

By the end of that first, giddy week, Bishop & Family was a success and Sarah knew that she and her sisters were at home. They turned one of the small attic rooms into a bedroom, patching curtains together out of old clothes and dust cloths, and painting the walls in all of the colours that they liked, before painting patterns on all of the tiles in the bathroom next to it and putting fresh flowers in a mug on the windowsill. Downstairs, they polished all of the floorboards until they shone and Lily taught herself how to make lace mats which she then placed underneath every cake in the window.

One day a woman from the council came into the shop. She explained that she was worried about how Georgia and Lily had not yet joined a school and needed to check if they were receiving a proper education. Sarah had pointed out that they were fifteen years old and even if they did join a school, they would be leaving it by the end of the year.3 She then decided to also point out that the twins were fluent in Italian and English and a handful of other languages thanks to all of the tourists that had come into 21Mrs Bertolini’s best friend’s great-niece by marriage’s bakery, that they could do the sort of mathematics that you or I would need a piece of paper and several hours to work out, and that they could make pastries so rich and delicious that you would almost weep to see them. And if all this was not good enough, the two of them also volunteered in the bakery at the weekend and could serve a queue that went out of the door without breaking a sweat. The woman from the council was convinced by this argument and even more so when Sarah sent her home with a scone that was so gentle and soft that it was like holding a cloud in her hands.

Now, I know that you may be thinking at this point that “all of this is very lovely to read about but we were promised a missing nun and three small girls who are very good at finding things that are lost and you haven’t given me anything that looks like that yet”.4

But there are things you need to find out before we can get to that part.

Trust me, though. There was so much yet to come for Sarah and Lily and Georgia and June—

Ah. You don’t know who June is yet.

Well, I’ll tell you all about her now.

1 Just in case you do not know what an “&” is, it is a fancy way of saying “and” but putting a squiggle instead.

2 This bakery is going to be very important in everything that follows from this point so Do Not Forget It.

3 At this point in time, children could leave school when they were fifteen years old. Before this, children could leave when they were fourteen years old and many years before that, they could leave when they were twelve or thirteen.

4 Also you might be thinking, “This bakery sounds great but I am Quite Hungry now and you didn’t prepare me for that in the slightest,” and if you are, I really very much understand and recommend that you eat a pink wafer before the next chapter because it’s only going to get worse.

KALE SOUP

One day the bakery door opened and a young girl ran inside.1

“Hello,” said Sarah.

“Hello,” said the girl. “I need your help. I’m running away from school.”

“Which school?” Sarah asked calmly. “There’s no school here in the village.”

“It’s up in the woods,” said the girl. “Quite the hike really. Anyway, it’s awful wherever it is. They make us eat kale soup. Can you imagine?”

Sarah pulled a face. “I’d rather not.”

“I knew you’d understand,” said the girl. She sighed in a rather resigned fashion. “Honestly, between you and me, I’m not very good at running away. This is my nineteenth attempt and I haven’t got it right yet.”2

23“So you came into a bakery,” said Sarah. “Between you and me, I don’t think this one is going to work out well either. Sorry.”

The girl nodded. “It’s because I want something nice to remember before I go back. I just walked right past one of my teachers and he looked at me and then I looked at him and all I could do was run and I’ve run a lot today because I had to get through the wood before anybody had noticed that I’d gone and now I’ve ruined everything. He’s only minutes behind me. All I’ve got left are these last few minutes of freedom.”

Sarah took a deep breath. “That’s a lot to take in.”

“I know,” said the girl. “I haven’t even seen cakes for weeks.” She looked around her and visibly relaxed. Sarah had been baking bread that morning and the shelves were packed with her efforts. She had made Vienna bread and long, slender baguettes, tiny, twisty knot rolls and dusty white bread buns, and it was one of the most beautiful things that the girl had seen for a long while. “Do you bake everything here? I want to be a baker when I grow up. I’d love to have a bakery like this. Can you imagine? Nothing but Victoria sponge every day? Oh it would be perfect. Sorry. I’m babbling. It’s just—it’s so perfect in here. You must be so happy. Sorry.”

“It’s all right,” said Sarah. “I understand how you feel. You don’t have to apologize to me about that.”

The girl gave her a quick, shy look. “Oh I always have to apologize.”

“Not here,” said Sarah. She had spent years trying to 24figure out why the widows had saved her and now, all of a sudden, she understood. “What’s your name?”

“June Mortimer,” said the girl.

“My name’s Sarah Bishop. You can come here any time you like.”

“They’ll never let me come back.”

“They will,” said Sarah.

The door to the bakery opened again. This time, it was for a tall and slender and deeply unimpressed looking man. He was very red in the face and had clearly run for much longer than he was comfortable with. He looked at June first and then at Sarah. “My apologies,” he said, clearly meaning none of it, “but this girl is not supposed to be here. I will punish this runaway severely, you have my promise.” And this part, he clearly meant.

“Hang on,” said Sarah.

The man coughed. “I’m sorry, Miss—er—I don’t know your name—?”

“Sarah Bishop, Mr—?”

“Mr Miniver,” said Mr Miniver.

Sarah gave him a bright smile. “Mr Miniver, June wasn’t running away in the slightest. She was coming here to get the food order to take it back to the school, just as she’d been asked to do.3 And in fact, I know that June will be coming here every week to pick it up as well, 25but she was just telling me that she needed permission from one of the most senior and responsible members of staff such as yourself in order to do so.”

Mr Miniver stared at her. “What?”

“It’s all been arranged,” said Sarah, who was rather enjoying herself. “So if you’ll give June permission to come along every weekend to pick up the order for you all, I think I can find something for you to enjoy as well. A little extra. In fact, I insist. You look like the sort of man who deserves a pastry. A bonus. Something to eat outside while I get the order ready for June. Does that sound like a plan?”

Mr Miniver looked at her. He looked at June. And then he looked back at Sarah. “You wouldn’t—you don’t—happen to have any chocolate éclairs, do you?”

1 And over sixty years later, that same girl would— Hang on. I’ll tell you all about that bit shortly.

2 The selected highlights of June’s previous Rather Poor Attempts At Running Away: buying tickets from and then being promptly sent back to school by Margaret-who-sold-the-tickets-at-the-train-station; being caught by the headteacher who was buying a sausage roll for his lunch and had Quite The Quick Reflexes when seeing an Unexpected Pupil walking by; and finally, missing the one bus out of the village because she was distracted by the smell of bacon sandwiches at the local café.

3 You will note that Sarah did not tell Mr Miniver who had given June permission to do this and that was because she was rather brilliant indeed.

A CAKE HEART

When Mr Miniver went outside to eat his chocolate éclair, June did not breathe until the door had closed behind him. It was only then that she turned around and said to Sarah, “Why are you helping me?” It was such an unusual thing for adults to do, especially to people like her, that she was quite baffled by it.

“You remind me of my sisters. If they were ever in trouble like this, I’d want somebody to help them.”

June looked suddenly interested. “Do they go to my school?”

“No,” said Sarah. “They don’t go to any school. I taught them everything I know and then we just get books for everything else.”

A dreamy expression of longing passed over June’s face. “I’d love that. Learning what you want to know. Do you know what my school is like? We learn about how to have neat handwriting and every now and then, if somebody wants to be really exciting, they teach us how to iron shirts.”

“Your parents must have thought it was the right school for you, though?”

“Any school would have been the perfect school for me,” said June darkly. “They’d have sent me anywhere 27that meant that I didn’t go home for holidays. I haven’t been home for years.”

And it was then that Sarah said something rather unexpected. “How old are you?”

“Fifteen,” said June, startled. “I only have a few months left at school until I can leave and when I do, I won’t look back.”

“Well then,” said Sarah, who had been having an idea for the past few minutes and felt that now was the time to share it, “how about I offer you a job?”

And this was such a remarkable thing for her to say that June did not say anything at all.

Sarah continued. “When you leave school, you can have a job here. No questions asked. It’s yours if you want it. Full time. Paid as well as I can make it. Until then, you can come every weekend and I’ll teach you everything I know. You said you wanted to be a baker so I’m going to give you that chance.”

June stared at her.

Even the thought of it was enough to fill her heart with hope.

“I’ll make it work,” said Sarah. “Every Saturday and the moment that you leave school, you can come here. I mean, only if you want—?”

“More than anything,” said June. She could not quite understand how her world had been so painful and so wrong for so long and now, all of a sudden, it was finally starting to feel like it made sense. “I just don’t understand why you’re being like this to me.” 28

“You’ll understand it all one day,” said Sarah. “But for now, start with this.”

And she gave June a biscuit.

LIKE A PLAN COMING TOGETHER

And so June Mortimer began to visit the bakery every Saturday and even though it was just for a few hours, and sometimes for even less, those were the happiest days of her life. Sarah taught her how to make cakes speckled with chocolate chips, and how important it was to eat them when they were still warm from the oven rather than let them stand and go cold. She taught her about how sweet and fudgy dates could be, and how to make a sticky and rich parkin that tasted of bonfire night and fireworks, and how to make twists of pastry so crisp with sugar, that biting into them reminded you of the first frost of winter.

When June was not baking or waiting for her lift back to school, she would squeeze onto the back step of the shop with Lily and Georgia and the three of them would plan their future together because they knew that they would never be apart. The precise details of this future remained imprecise for some time until the great day when Georgia suddenly worked it out. She said, “We’ll run a book-café,” and it was all so startlingly perfect that Lily and June stopped everything that they were doing 30and paid complete attention. “We’ll serve books and cakes and we’ll stop everything for afternoon tea.”

“Oh, yes,” said June. She felt rather dazzled. “Yes. Of course. We couldn’t do anything else. It’s a wonderful idea. I’ll bake and you can sell the books and Lily can look after people, and then Sarah can retire and take some time off and put her feet up.”

“Well, we wouldn’t let her do a thing at the café,” said Lily. “She’s so tired all the time, and she needs to rest. If she wanted to, she could lead a baking demonstration every now and then but that would be absolutely it.”

Georgia nodded with approval. “Oh just imagine it—we would have cake everywhere.”

“And everything that we sell would be wrapped up like a birthday present,” replied June. She felt suddenly feverish with excitement. She could almost see it all right there in front of them. It was so real. “We could tie ribbon around every book when it’s sold, and wrap it in tissue paper the same colour as well. And have little boxes for people to take away their cakes in. And we’d make miniature Victoria sponges too, just the perfect size for one person to eat entirely to themselves.”

“And there’d be absolutely no kale,” said Georgia, who had heard a lot about the catering choices at June’s school.

“Or anything green anywhere,” said Lily with a bright grin. “Unless it’s icing.”

“We should call it Bishop & Mortimer,” said June.

For a moment nobody moved. In the distance, they heard the shop bell ring and then the sound of Mr Miniver 31chatting to Sarah. He had started turning up early to pick up June so Sarah had started to distract him with a chocolate éclair that had to be eaten before he left. It only gave June a few minutes extra with her friends but that day it felt like everything.

Lily reached out to take one of her hands and Georgia the other.

“To Bishop & Mortimer,” said Lily.

“The three of us together forever,” said Georgia.

“Forever,” said June. “Forever.”

THE BEGINNING OF A BEAUTIFUL FRIENDSHIP

From that point on, the friendship between Georgia, Lily and June became as solid as stone. Georgia helped June out with her homework and the two of them would sit on the floor behind the shop counter as Lily helped Sarah make croissants for the Sunday morning rush. When the homework was done, Sarah would teach June about how to make the perfect ganache or how to make butter icing that was so tasty that June wanted to eat nothing else for the rest of her life. And at the end of the day, when they closed the shop at five p.m, they would sit together and eat anything that hadn’t been sold before Mr Miniver arrived to take June back to school.

June held on to that friendship like gold and the memory of it got her through the long and lonely days at school. She would think of Lily and Georgia whenever they were served kale soup for lunch, and she would think of Sarah’s warm and welcoming hugs whenever all of the other girls got a letter from home and she did not. And whenever all of this was not strong enough to keep her sadness at bay, she would pull out her notebook and fill it up with ideas for Bishop & Mortimer. She would 33sketch how the building and the menu might look and share this with Georgia and Lily at the weekend, and when they gave feedback or new ideas, she would spend the next week refining them.

June took the notebook down with her one Saturday to share her ideas for the perfect Victoria sponge. It was a particularly busy day and Sarah had been feeling tired so she did not get a chance to do this until late in the afternoon, only a handful of minutes before she was due to be picked up and taken back to school.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)