Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

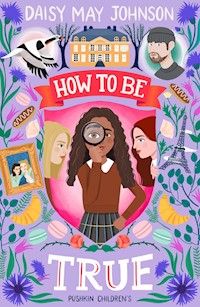

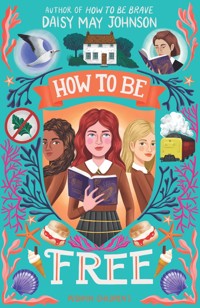

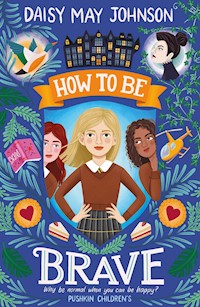

- Serie: How to Be

- Sprache: Englisch

Edie was born to a family of troublemakers. When her activist parents leave Paris to protest around the globe, her grandmother decides it's time she became a proper young lady and so sends her to the School of the Good Sisters.But to Edie's surprise, the nuns at the school teach genuinely useful things, like how to build a perfect library, cater for midnight feasts and make poison darts, and mischievous Edie feels right at home. When a school trip to Paris is planned, she worries about returning to the strict order of her grandmother's chateau - but things are not as she left them. Soon Edie and her rebellious friends are caught up in a mystery involving a precious painting, secrets from her grandmother's past and a very persistent burglar...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 346

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

THIS IS A STORY ABOUT THREE THINGS

1 I am also very easily distracted by second breakfasts, elevenses, afternoon tea, supper and midnight feasts. In my defence, Good Sister Honey really is a remarkable caterer.

2 This is a footnote. It is the second footnote on this page so go back up and find the first and then things will all make sense. Or, alternatively, just read the paragraph above this one. You are in charge!

3 You might be wondering who and indeed what a Good Sister is. They are nuns and they are rather fabulous. I should know, for I am also a nun. My name is Good Sister June, I am the Headmistress of a very remarkable school, and I am very fond of Victoria sponge. And that, my friends, is the sort of secret that a footnote is perfect for.

A GIRL NAMED MARIANNE

When she was fourteen years old, Marianne Montfort had been sent out to find a job. She was not particularly happy about this, but she had not been happy about anything since her family had moved to France and left the country of her birth far behind. It was the sort of sadness that had begun to rule her every waking moment. She would find it talking to her as she laid the table for lunch, or whispering in her ear as she tried to make friends at school: You do not belong here, this is not your home.

Her parents knew about this sadness, for they had their own. Her father had started a new life teaching at a university in Paris and felt that somebody would tell him that they had made a mistake with every lecture he took or student that he spoke to, and her mother had found a job in a local shop and bit her tongue when somebody pretended that they did not understand her accent or what she was saying to them. It was only the knowledge that their family was safe and together that kept their sadness and worries at bay.

Marianne’s sadness, however, lingered. Her parents watched it wrap around her and slowly pull their daughter away from the world. She began to stay inside the house and stay home from school and every day saw her grow quieter and paler and stiller. And so they came to a decision. Marianne must be sent out to find a job that would distract her from her sadness and pull her back into the world.

And that was the day that she found a very small and very revolutionary plant shop on the Rue de la Vérité.1

1 There will be a lot of French phrases in this book. I will tell you what some of them mean, but not all of them. I think you’re smart enough to work out what they mean if I don’t.

A SMALL AND REVOLUTIONARY PLANT SHOP

The owner of the plant shop was called Madame Clement. She was a tall and big woman, full of power and strength and heart, and over the years they spent together she taught Marianne everything she knew about plants. She taught her how to bring a Snow Orchid back to life with nothing but words, how to make the Slate Rose bloom for weeks on end, and how to make the Iron Lilies in their shop grow taller than anywhere else in the city. She taught her what chemists grow in their gardens,1 what you call a nervous tree,2 and why herbs were the most supportive plants of all.3 And in between all of that, she taught Marianne how she could help make a better world.

“It’s not that you have to make all of it better,” said Madame Clement, as she nibbled on the end of a pain au chocolat.4 “But you should try to make your little bit of it better. If everyone does that for their little bits of the world, then just imagine what happens when all those little bits come together.”

And so, as soon as they opened the shop, Madame Clement sent Marianne out to deliver flowers and plants to all of the other shop and restaurant owners on the Rue de la Vérité. The Italian brasserie run by old Signore Alberici5 received a pot of silver thyme to flavour his meals while the young new owner of the chocolate shop, Madame Laurentis, received a bunch of roses as brightly coloured as her hair. A random passer-by on their way to work was given a plant to take into their office while the street cleaners received daffodils that were still wet with dew. There were some days that Marianne thought they might run out of things to sell because they’d given so much of it away, but the shelves of the shop never looked empty.

On the days that it rained or snowed, Marianne stayed inside the shop. In a way, she liked those days best for she could learn directly from Madame Clement herself. She learnt how Madame Clement gave shelter to students with nowhere else to go; how she pressed food into the arms of the homeless and helpless from the windows at the back of the shop and how she helped the local school children plan their protest against the horrors of their new school menu.6 Marianne helped Madame Clement clean out the cellar of the shop so that the single mothers could meet and let their children play in safety together; she watched as Madame Clement let the activists plan their revolutions in there in the evenings, and the street artists store their kit inside the shop when it rained.

Every single second that Marianne spent with Madame Clement felt like a gift.

1 Chemist Trees.

2 A sweaty palm.

3 Because they are full of encourage-mint.

4 This is a type of pastry full of chocolate, and the fact that Madame Clement liked to eat them for her breakfast should tell you how good an egg she really was.

5 There was a rumour that he was about to retire and sell up to a nice young couple from Germany. As you will see shortly, he does and they are very nice indeed.

6 There was far too much kale and nobody liked that.

THE GREATEST OF ALL GIFTS

Madame Clement left the shop to Marianne in her will.

MARIANNE MONTFORT AND JEAN-CLAUDE BERGER

Marianne loved that shop so much that, on the day her parents told her that they were moving to a new country and starting a new life all over again, she decided to stay in Paris. She had spent her life looking for somewhere that she belonged, and the plant shop, with its windows full of sunlight and shelves full of green, had become precisely that. She packed it full of unusual and odd plants, the sort of things that you could see nowhere else in Paris but there. She planted an Egyptian walking onion outside the front door and whenever it was picked, the scent of onions would roll down the Rue de la Vérité, whilst inside, ghost orchids and bat lilies and hundreds of other plants filled every inch of free space. In the middle of it sat Marianne like a queen, and she carried out Madame Clement’s wishes for liberty and equality with all her heart. She let the feminist students meet for free in the room above the shop to plan their next adventures, the homeless find somewhere warm and safe for the night in the cellar below, and she handed out biscuits to those who were lonely and asked them to stay and talk to her for a while.

On the rare occasions that Marianne’s sadness tried to be a part of this brave new world of hers, the light streaming in through the windows or the bright, fierce colour of the bougainvillea made it fade away into nothing.

And then, one day, her sadness stopped coming entirely.

THE DAY THE SADNESS STOPPED

Jean-Claude Berger did not arrive at the plant shop on purpose.

He had turned left down a street that he had thought looked familiar before realizing that it was not, and only stubbornness and the sight of his family’s château, perched high on the hill in the distance like some tempting fruit from a tree, kept him going. But the streets of Paris were against him, and they kept twisting away from the château and taking him somewhere else. A brasserie spilling out onto the pavement; three old men playing belote with each other outside their homes; a row of bicycles locked to each other; and then the Seine, the river itself, glinting in the bright sunlight. A perfect city to be lost in, at a perfect time.

In many ways, Jean-Claude was content with being lost, for he knew that it was only through being lost that you can find yourself. He had spent many years at a dark and grey school in England, where the boys were very good at being lonely and not very good at making friends with each other. He had been sent there by his grandmother following the death of his parents.1 Odette Berger2 had not known what else to do with the small and bright-eyed child that had been presented to her, and so she had sent him away in the hope that others might know better. But the school was strange and sad and cold, and all too fond of serving the children kale.3

Jean-Claude had not enjoyed it one bit. He had kept himself happy and sane by fighting back against the authorities wherever he could. He protested everything from the presence of broccoli soup on the menu through to the mandatory cold showers after PE. The staff had responded to his rebellions in the only way they knew how: lines, detentions, being sent to bed without supper and, after Jean-Claude had climbed onto the roof and unfurled a banner that said, ‘this school is not nice’ on Visitors’ Day, expelling him.

And expulsion was the best thing that could have happened to Jean-Claude, for it set him free.

1 Jean-Claude’s parents, Bertrand and Natalie, died in a car crash when Jean-Claude was very young. It was because of this that he had almost no memories of them to hold onto as he grew up. Sometimes this made him feel very lonely but at other times, it made him feel very little at all.

2 Remember this name. She is Very Important.

3 And if this does not give you an idea of how horrible it was, then nothing will.

THE FREEDOM OF JEAN-CLAUDE BERGER

When the school telephoned her, Odette sent Jean-Claude the money to return home. He refused it, for a part of him wanted to discover the world upon his own terms and without the help of his privileged family. He went to London and found a job and then a room, paying with the last handful of money he had to his name, and it was there that he learnt about a world that he didn’t even know existed. He went to meetings and lectures held by people who were making a difference in the world, and realized that he wanted to do the same. He wanted to use his money to help people. He wanted to make a difference with it.

And so, at last, he began to make his long and slow way back to Paris to do precisely that.

When he found himself lost on the Rue de la Vérité, he did not realize that his future wife was there to greet him. Of course Marianne did not know this either. All she knew was that a young man had stopped to study the window of the plant shop where a row of quite delightful tiny plants and equally delightful feminist slogans1 jostled for attention.

After a while, he nodded to himself as if satisfied, and came into the shop.

1 ‘Plants Not Patriarchy’ and ‘Bloom for Yourself and Not for Others’ and ‘Make Compost Not War’.

PICKING THE RIGHT POT PLANT

“I wish to purchase a present for my grandmother,” said the man with bright blue eyes to Marianne. “I’ve been away from home but now I’m back. Your display caught my eye and I thought that a plant might be a good idea. I don’t know what to pick. She’s kind of difficult to buy for. There’s only the two of us, and I’ve been gone for a while and… you don’t need to know all of that. Do you have any suggestions?”

Marianne nodded. The choosing of plants was a slow and quiet thing, one that took time and thought, and so she played for both by asking him about the weather. And then his journey. And why he’d been away. They were small and vague questions to ask and his answers were not important. What mattered was the way he gave them, and the way he looked as he did so.

When he finished speaking, Marianne picked out two plants and put them on the counter between them. One of them was perfect and one of them was not. The perfect one was called Heloise and had been grown from a cutting from one of Madame Clement’s most beloved and elderly specimens. Marianne had not thought that Heloise would survive for she had turned brown and then yellow and after all of that, her leaves had begun to curl up at the end. Marianne had moved her around the shop from sunlight to shade, trying to find the best place for her and failing miserably. It was only when Marianne had placed her on a shelf with a direct and uninterrupted view of the world outside that Heloise had been happy. She was a plant that needed adventure and this man, Marianne knew, would give her that.

“One of these,” she said. “Either one will be fine.”

He picked the right one.

Of course he did.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER

Their daughter was born nine short months later. Her fists were balled tight as she came into the world and her eyes were bright with fire and life.

She was a baby born to change the world, and they named her Edmée Agathe Aurore Berger.

Or Edie, for short.

A REVOLUTIONARY CHILDHOOD

Edie Berger learnt what a protest was before she could talk. She went to one when she was just three days old, a tiny ball of noise and fire, wrapped in the arms of her mother and surrounded by thousands of other voices. Many other babies might have found the experience upsetting, but Edie found it exciting. It was like growing up in the middle of a whirlwind and knowing that she was in control of it all. She learnt how to read people and understand everything that they didn’t know they were sharing. By the time she was four, Edie could spot the signs of danger in a crowd of people,1 and how to get out of trouble before trouble even realized she was in it. By the time she was five, she could navigate her way around the city with her eyes (metaphorically) closed. She knew all of the bakers and the patisseries and which of them was the best at making bread and who could put together the most beautiful macarons.

Sometimes people who did not know Edie would grow concerned about her wellbeing. A small girl purposefully walking down the street by herself, with hair the shape of a wild storm cloud, would always attract attention. But whenever these people came towards her, the shopkeepers and locals would intervene and tell them that it was all right. Everybody knew Marianne and Jean-Claude, and their daughter. Edie had her mother’s soft brown skin, and her father’s wide and beautiful smile, and the neighbourhood loved her and looked after her as if she was their own. Madame Laurentis would give Edie a handmade chocolate as she wandered past her small and perfectly formed sweet shop, and a history book for Jean-Claude to read. Frau and Herr Bettelstein, freshly arrived from Germany and running the brasserie of their dreams,2 pushed fresh apfelstrudel3 into Edie’s hands and an order for roses from Marianne. And on the days that everybody was too busy in their shops and restaurants, old Monsieur Abadie would fold his paper and rise from the bench4 at the end of the Rue de la Vérité and escort Edie back home to the plant shop.

Although they all had rooms at the family château way up on the hill, Edie and her parents tended to sleep in the basement of the plant shop, the three of them wrapped up in rugs and cushions and caring for nothing other than being together. Each night, Jean-Claude would tell his small daughter bedtime stories of the brave and remarkable women in France. He spoke of people like Joan of Arc and George Sand and Louise Michel, and even though Edie did not quite understand everything that he said, she knew that the stories made her heart sing.

“But that’s what they should do,” said Jean-Claude when Edie told him this. He gave her a little squeeze of pride. “Stories don’t just stay inside a book. You carry everything you’ve read inside of you, and when you need them, it’s the memory of those stories that will help you figure out what to do with your life.”

And when he said that, Edie realized that she was going to change the world.

“I’m going to change the world,” said Edie.

“Quite right too,” said Jean-Claude. “I’d expect nothing less.”

1 “What you have to understand is that there’s a moment where people stop thinking about what they should be thinking about, and start thinking about something else entirely. And the problem comes when they start thinking about the wrong thing.” And because this is possibly the clearest thing I have ever heard Edie say, I have included it here in its entirety.

2 Signore Alberici had, at last, retired and sold his brasserie. He had gone off in a camper van to tour the world, selling pizzas at the roadside to fund his travels. If you ever are lucky enough to come across him, I particularly recommend his spinach and ricotta pizza.

3 A particularly delicious pastry involving apples, sugar and lots of love. Good apfelstrudel comes from the heart, and the one that the Bettelsteins made was one of the best in the entire world.

4 The bench was dedicated to Lizette, which was a name that meant nothing to the neighbourhood, but I shall tell you: it was the first name of Madame Clement. Lizette Clement had been somebody that Monsieur Abadie had loved very much, and she had loved him back. He had paid for the dedication himself and had it put on the bench one night when nobody was around. And every morning when he sat there with his newspaper, he thought of the girl he had loved and his heart became full with a fresh-found joy because of it.

LIKE OIL AND WATER

Throughout all of this, Edie’s great-grandmother1 was kept at a distance. It was not that Edie did not want Odette to be in her life, or that Jean-Claude did not want Odette to be in his, but it was more the fact that none of them quite knew how to do it. They tried of course, in that rather complicated and not very useful way that adults tend to do such things. Jean-Claude would help Odette by picking up her shopping and Odette would say thank you by inviting him, Marianne and Edie every weekend for lunch. And even though they always went, none of them enjoyed it.

“It is necessary,” said Marianne when Edie told her how she felt. “I know it’s awful, but you have to get to know her. Odette is the only family that you have in this country other than us. My parents are halfway around the world. You need to know who will look after you here, in case something ever happened to us. Do you know what I mean by that?”

“I do understand your point, but also I do not want to,” said Edie with great honesty.

“That’s good enough for me,” said Marianne. “Come and help me deadhead the daffodils.”2

And so that was the end of it: Odette was in Edie’s life, and Edie would be in hers, even though neither of them liked it one bit. Odette did not like the way her granddaughter walked, or the way she talked. She insisted on calling her Edmée which was as foreign to Edie as flying; she did not like the way Edie sat,3 or the stories that she read, and she definitely did not like the fact that Edie was going to follow her parents into activism when she grew up.

“Activism isn’t a career,” said Odette when she learnt this.

“Neither is being horrible,” said Edie, when she heard this.

“Would you like some more peas?” said Jean-Claude, when he deliberately ignored all of this.

Edie did not like the way her grandmother kept rooms in the château locked from anybody but herself. She did not like the way that Odette spoke about the priceless paintings in her collection but refused to show them to anybody. Art was not for hiding in Edie’s world. It was for propping up on the walls of the plant shop and letting the young babies who could barely hold a pen draw on it. It was for helping people see the possibilities of the world that they lived in. Nobody could see the possibilities of Odette’s art collection. Any time Edie even as much as looked at the room, Odette clicked the lock shut and placed the key in her pocket.

On one particularly frustrating day, Edie had asked her father about it. “Have you ever been in that room?” She had watched Odette carefully go into the room and close the door behind her. When Edie had tried to open it, the door had been locked.

“Yes,” said Jean-Claude. “A long time ago. Does it really matter though? Everyone must have secrets, and that room clearly holds hers.”

“But I want to know what’s in it,” said Edie. “And even though you are quite reasonable and calm sounding right now, I think you want to know as well.”

Jean-Claude shrugged. “I did,” he said. “But now I want to know so much more than that. The world is an expanse. It waits for us all. ‘Awake, arise, or be for ever fallen!’”4

It was the sort of reply that didn’t make sense. It was also the sort of reply that bordered on being slightly irritating. And his daughter was not the sort of person to let that go without comment.

“That doesn’t make sense,” said Edie. “Also it borders on being slightly irritating.”

“It will make sense,” said Jean-Claude.

And on one too-soon day, it did.

1 Technically Odette is Edie’s great-grandmother, but as Jean-Claude’s parents were not alive, they had always called each other grandmother and grand-daughter. Admittedly they had also called each other a lot of other names but because some of them were less than polite, I shall not repeat them here however much Edie might want me to. (Yes, she is standing right behind me as I write. Yes, she SHOULD be going to her lessons instead.)

2 This sounds very dramatic but it is just pulling the dead bits off the plant and leaving the live bits on.

3 Odette was fond of people who sat quietly in the corner and didn’t get into any trouble whatsoever. It will shock you to discover that Edie was not—and never would be—one of these people.

4 This is a quote from a very long and occasionally very brilliant poem called Paradise Lost. It is quite complicated to read, however, so I recommend waiting a few years and then making sure that you’ve got a custard cream to hand.

LIKE LEAVING HALF YOUR HEART BEHIND

“I’m sorry,” said Marianne. “Things are… complicated.”

“You should be sorry. You’re leaving me behind,” said Edie. She glared fiercely at her parents. “You are going abroad and leaving me behind and what is worse, you are leaving me with her. That does not feel complicated at all.” A part of her felt like crying, but another, much more interesting part, felt like throwing a lot of things onto the ground and jumping upon them. She was only stopped from doing this when her father raised his eyebrows at her. She could tell that he didn’t understand her reaction. Sometimes her parents could understand the feelings of everybody but her. It was one of the problems of having parents who were so good at what they did.1

“Tell me what you’re thinking,” said Jean-Claude, who was also very good at realizing that Edie wanted to say something and didn’t know where to begin.

“I am thinking that sometimes I wish you were not so good at what you do,” said Edie.

“We are only good because we have the money and the time and the resources to be good at what we do. I spent years hating everything that my family had until I realized what good we could do with it. We can use all of those resources and the time and the money to make the world a better place.

“There are people who need somebody to help them, and we can do that. Not many people have that chance but we do. We can support the people who need help and give them anything they need. We can be there for them when nobody else is. We can help to fight the battles that they need to fight.

“But your mother is right. All of this comes at a price. We are going to be visiting places all around the world, and not all of them will be safe—”

“I can look after myself,” said Edie, interrupting.

“I know,”2 said Marianne, “but we’re going to be working with activist organizations all around the world. Armies too. Some of the things we do may be dangerous. And we won’t be able to do any of that if we’re worrying about you. Odette will look after you. She is your family.”

It is in such moments that the world can be torn apart, and so it was with Edie.

And even though she did not quite believe it was true or that it would even happen (for her parents were particularly talented at planning schemes that did not Always Come Off) it was only a week later that she found herself standing on the front doorstep of the château.

Saying goodbye.

1 If this sentence does not convince you of Edie’s raw and wonderful and unrelenting love for her parents, then I do not know what would. As she told me once, they were idiots but they were her idiots, and that was what mattered more than anything else on the earth. (And then, because she had been far too sincere for too long, she threw a stink bomb at a passing first year before climbing out of the nearest window.)

2 There were many doubtful things inside Marianne’s mind, but the one thing she did not doubt was the remarkable strength of her daughter.

HOW TO SAY THE IMPOSSIBLE

Marianne bent down and wrapped her arms around her daughter and squeezed her very tight. “Remember this,” she said, with her face buried in Edie’s hair. “Remember the way that this feels, that it is me, remember that, even if you forget all else.”

And after a long while, when neither of them had spoken or even remembered what words were, Marianne stood up and walked towards the waiting taxi. She did not look back. I do not think that she could, not with half her heart left behind her.

Jean-Claude touched his daughter’s face with his hand and looked deep into her eyes. “You must represent everything about us while we are gone,” he said. “You must be true to yourself and to us. It might seem for ever but I promise it isn’t. Time is just a blink of an eye. The hours will pass. The weeks will fly by. And as soon as we can, we will come home and be together again.”

It was then that it all became real.

Too, too real.

“Let me come,” said Edie in a voice that nobody heard, not even herself. She said it again as Odette and Jean-Claude embraced and said farewell,1 and she said it again as Jean-Claude got into the taxi. She said it again as the engine started up and then she found herself repeating it constantly, softly, painfully, all the way until the taxi has driven down the hill and out of view.

And then she did not say anything else, for there was nothing left to say.

1 Sometimes adults do tend to do what they think they must do, rather than what their heart tells them. This moment between Jean-Claude and Odette was precisely that. And the fact that they did not tell each other the truth about how they were feeling is perhaps the saddest moment in this entire book.

THE NEW WORLD OF EDIE BERGER

And so, a new life began for Edie even though she was not ready nor willing nor able to receive it.

The plant shop was given over to the care of Isabelle Tremont, a friend of Marianne’s, and Edie was given a bedroom on the top floor of the château. It was surrounded by empty and abandoned rooms; some of them full of furniture that had been forgotten for many years, and others packed full of nothing more than long and lace-like cobwebs. It was a space that was perfect for adventure, but Edie could not see it then. She was far too busy nursing her broken heart and trying to ignore the fact that every day she spent without her parents made it break a little bit more.

It did not help that life with her grandmother was complicated at best. Odette was an early riser, fond of being awake for hours before the sunlight, and there were some days when Edie did not even see her. She would climb down the long and lonely stairs and be given her breakfast in the dining room and she would spend hours wandering around the house until somebody remembered her lunch and then somebody else remembered her dinner. And throughout all of that, Odette wouldn’t be anywhere to be seen.

Edie knew where she was, of course. Everybody did. Odette would go to the safety and silence of her art collection, and each time she did, the door was firmly locked behind her. She would spend hours there by herself with the paintings and sculptures and when Edie tried to ask her about it, Odette would close up and change the subject. She would say “Have you done your homework?” on a Saturday, or “Have you had your supper?” when it was only just eleven in the morning and so, eventually, Edie stopped asking and began to sneak out of the house instead.

The first time that she did it, Edie did not quite know what to do with herself. The city was so indelibly marked with the memories of her parents that a part of her did not want to go into it, and yet another, greater part made her start to walk in the direction of the Rue de la Vérité.

Madame Laurentis was the first to greet Edie. She raced out of her shop and gave her a heartfelt hug and a box of chocolates. “Keep them to yourself,” she advised. “I will send chocolates up to the château for your grandmother, but these are all for you. Sometimes we should treat ourselves first and you, my dear child, look as if you need a treat more than most.” She was not wrong.

All of the other shop owners saw the changes in Edie and reacted the only way that they knew how. Frau and Herr Bettelstein gave her some freshly baked rye bread sprinkled with caraway seeds on top.

“It is my favourite,” said Frau Bettelstein, smiling conspiratorially at Edie. “Everything is better when you have fresh bread, I think.”

Monsieur Abadie even escorted Edie back to the gate of the château and pressed a slab of toffee into her hand. “As I am an adult, I must tell you not to eat this before your meals,” he said quietly, “but I would not listen to me. I have known a lot of stupid adults and only a handful of stupid children. You, my child, are not one of them.”

And between them, Madame Laurentis and the Bettelsteins and Monsieur Abadie managed to keep Edie going. They handed food out to her every time they saw her,1 and pretended to not notice when she had a tiny cry in the back of their shops or wiped her eyes in the windows of the brasserie. They were good people and their love for her was enough to make Edie’s long and lonely nights in the château feel bearable.

But nothing good lasts for ever, and the Rue de la Vérité began to change. Monsieur Abadie went into hospital for his long-awaited operation and his bench turned cold and empty without him. The brasserie grew busier and busier and all that Herr and Frau Bettelstein could do was smile at Edie as they rushed past her. The chocolate shop suddenly became famous thanks to the review of a local writer and so customers began to queue out of the doorway, each and every day, and all Madame Laurentis could do was wave at Edie as she walked past the shop’s window.

And as the sadness began to build inside her heart once more, Edie decided to deal with things in the only way she knew how.

1 I feel like I must emphasize here that Odette was not starving Edie. Far from it. Edie had three very good meals a day and all the in-between meals that she liked. In a way, the food that she was given on the Rue de la Vérité was not really food at all. It was a way for people to tell her that they loved her and cared for her and I think there is nothing more beautiful than that.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)