1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

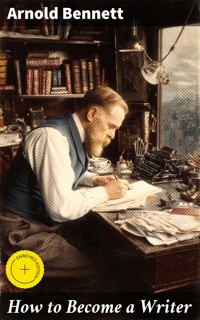

In "How to Become a Writer," Arnold Bennett offers a candid, insightful exploration of the writer's craft that serves as both a manual and a philosophical treatise. Bennett's prose is engaging, infused with clarity and humor, as he demystifies the process of writing, addressing various facets such as inspiration, discipline, and the nuances of style. Influenced by his own experiences during the early 20th century'—a time marked by industrial change and innovation'—Bennett situates his guidance within a broader literary context, encouraging aspiring writers to find their unique voice amidst a burgeoning literary landscape. Arnold Bennett, a prominent figure of the early 1900s, was deeply entrenched in the cultural and social shifts of his time, which steered his literary pursuits. Having transitioned from journalism to fiction, Bennett's own journey as a writer informs his pragmatic and comfortingwisdom in this book. He draws from personal anecdotes, revealing the trials and triumphs of honing one's craft, providing insights that resonate with both novice and seasoned writers alike. For anyone seeking to refine their writing skills or embark on a literary journey, "How to Become a Writer" stands as an essential guide. Bennett's accessible approach and profound insights not only equip readers with practical tools but also inspire a deeper appreciation for the art of writing itself. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

How to Become a Writer

Table of Contents

Introduction

At its core, this book contends that literary ambition becomes real only when it is deliberately translated into routine practice, where attention, perseverance, and craft displace mystique, and where the would-be author learns to treat inspiration not as a rare visitation but as the cumulative result of steady reading, thoughtful observation, purposeful drafting, and continual revision undertaken with humility, realism, and the willingness to work, so that the dream of authorship is no longer an abstraction but a disciplined habit of mind and hand sustained over time in the face of distraction, doubt, and the ordinary pressures of life.

Written by Arnold Bennett, a prominent English novelist and essayist of the early twentieth century, this concise work of nonfiction belongs to the tradition of practical literary counsel. It emerged within a period of energetic British publishing and periodical culture, when questions about professional authorship, training, and readership were widely debated. Rather than meditating on art in the abstract, it addresses the aspiring writer directly, assuming a contemporary audience curious about how writers actually work. In this sense, its setting is less a geographical locale than an intellectual climate: a moment when craft, self-management, and cultural participation were treated as learnable, sharable skills.

Readers encounter a compact, commonsense guide that frames writing as a vocation grounded in method. The book does not promise secret shortcuts; it offers a clear-eyed view of habits that foster progress, from cultivating attention to language and experience to managing one’s time with purpose. Bennett writes in a voice that is lucid, urbane, and brisk, favoring illustrative reasoning over ornament. The mood is encouraging but unsentimental: the text respects ambition while refusing to flatter it. The result is an experience that feels both intimate and public-minded, a conversation pitched to anyone ready to exchange vague desire for deliberate practice.

Central themes include the tension between inspiration and discipline, the difference between talent and the skill that sustained effort can develop, and the role of reading as apprenticeship. Equally important is the idea that a writer’s material is found within everyday life, provided one learns to see and to render it with accuracy. The book also treats authorship as a profession requiring habits, standards, and resilience, not merely flashes of brilliance. Across these threads runs a consistent claim: writing thrives when it is organized, honest about its difficulties, and attentive to the reader, the sentence, and the incremental gains of repeated work.

Although rooted in its historical moment, the book’s relevance is immediate. In an age shaped by digital distraction and rapidly shifting publishing opportunities, its insistence on steady routines and clear priorities reads as timely counsel. It invites readers to assess how they spend attention, to convert intention into scheduled effort, and to value slow accumulation over instant results. The emphasis on learning by doing, cultivating judgment, and participating in a community of readers and writers speaks to contemporary concerns about sustainability in creative work. Above all, it reframes ambition as an ethic of practice—useful wherever craft must coexist with competing demands.

Stylistically, the prose is plain yet refined, designed to illuminate rather than dazzle. Bennett favors argument that proceeds step by step, linking attitude to method and method to outcome, so that exhortation rests on reason. The tone balances cordiality with firmness: the author writes as a capable mentor, neither coy nor severe, guiding the reader toward habits that can survive beyond momentary enthusiasm. Humor appears in measured touches, not to entertain for its own sake but to clear the air of pretension. The effect is a sustained clarity that demystifies the work without diminishing the dignity of the writer’s aims.

Approached as an introduction to the writer’s life, this book sets realistic expectations and invites commitment. It offers a way to begin, and to keep beginning: identifying obstacles, proposing workable responses, and aligning aspiration with achievable tasks. Readers will not find formulas; they will find a framework for building momentum, a vocabulary for thinking about effort, and a humane reminder that progress emerges from continuity. For anyone standing at the threshold of authorship, it functions as a steadying companion, encouraging clarity of purpose and the daily labor that turns a wish to write into the practiced habit of writing.

Synopsis (Selection)

Arnold Bennett’s How to Become a Writer is a concise, practical manual that treats writing as a learnable craft supported by steady labor. Opening with the difference between general ambition and a concrete plan, Bennett frames authorship as a series of manageable tasks rather than a mysterious gift. He advises readers to adopt a realistic view of the profession’s demands and rewards, stating plainly that progress depends on routine, not sudden inspiration. The introduction outlines the book’s purpose: to chart a step-by-step path from first intentions to disciplined output, while emphasizing clarity, persistence, and the importance of matching personal aims with market realities.

Bennett begins with self-examination, urging prospective writers to define their motives and the kind of work they intend to produce. He emphasizes the need for patience, resilience, and the ability to learn from rejection without discouragement. Reading widely is recommended to develop taste and technique, but he warns against slavish imitation. Observation of everyday life and the cultivation of a notebook habit supply raw material for future writing. He argues that reliable habits matter more than occasional enthusiasm, and that setting specific goals gives structure to practice. The early chapters thus establish attitude, preparation, and the foundations of a sustainable routine.

Time management follows as a central theme. Bennett counsels finding fixed hours for work, however small, and keeping them inviolable. He suggests beginning with short, regular sessions that accumulate skill and confidence, stressing that momentum arises from frequency rather than length. Practical measures—quiet space, a simple schedule, modest targets—make writing compatible with employment or family duties. He underscores the value of drafting quickly to discover ideas and revising carefully to refine them. The routine is presented as a self-training program: observe, note, draft, revise, submit. By insisting on predictability and accountability, Bennett converts aspiration into reproducible daily practice.

Turning to technique, Bennett focuses on clear prose. He urges precision in vocabulary, economy in sentence structure, and a logical flow between paragraphs. Style, he argues, grows from exact observation and careful revision rather than ornament. Exercises in summarizing, paraphrasing, and pruning help eliminate vagueness. He treats grammar and punctuation as tools for meaning, not decoration, and recommends reading aloud to test cadence and clarity. Concrete details and well-chosen examples anchor arguments and narratives. This section establishes the practical methods by which a writer moves from rough material to coherent copy, emphasizing that lucid communication is a professional obligation.

Bennett then addresses short nonfiction forms—articles, reviews, and essays—as accessible training grounds. He advises studying periodicals to understand their tone, length, and subject preferences, and tailoring submissions accordingly. Clear openings, focused arguments, and disciplined endings are emphasized, as is the practice of writing to a word limit. He outlines the basics of pitching ideas, delivering clean copy, and meeting deadlines. Rejection is framed as routine feedback rather than failure. By advocating steady production for specific outlets, he shows how early publication both sharpens technique and introduces the writer to the expectations of editors and readers.

Discussion shifts to short fiction, which Bennett presents as a laboratory for narrative craft. He outlines core elements—situation, character, conflict, and resolution—while encouraging close control of scope. Planning is recommended to avoid digressions, but he acknowledges that discovery can occur during drafting. He stresses the necessity of credible motivation, a clear throughline, and consistent tone. Attention to scene construction, dialogue, and pacing helps maintain reader interest. As with nonfiction, he recommends targeting appropriate markets, respecting length constraints, and polishing endings. Short stories serve as practice in structure and an introduction to the demands of magazine publication.

For longer work, especially the novel, Bennett highlights organization and endurance. He suggests early decisions on scale, point of view, and time frame, supported by outlines that remain flexible during drafting. Regular output targets prevent stalled progress, while staged revision ensures coherence across chapters. He recommends balancing composition with intervals for perspective, and keeping a record of characters, chronology, and themes to maintain consistency. Relations with publishers—synopses, sample chapters, and timelines—are treated practically. The chapter stresses patience: length magnifies structural problems, and only methodical planning, steady drafting, and systematic revision yield a unified, readable book.

Bennett devotes attention to the business of writing. He covers rights, contracts, and the difference between serial and book publication, advising careful record-keeping and prompt correspondence. Professionalism—clean manuscripts, punctual delivery, and responsiveness to editorial notes—is presented as essential. He discusses fees, expenses, and the advantages of diversifying work across reviews, articles, stories, and books. The importance of a dependable reputation is highlighted: reliability invites future commissions. Practical strategies for coping with uncertainty—maintaining a pipeline of submissions, learning from feedback, and aligning projects with viable markets—anchor his view of authorship as both craft and livelihood.

The book concludes by reinforcing its central message: writers are made by consistent practice, clear aims, and attention to readers’ needs. Bennett returns to the virtues of discipline, observation, and revision, noting that skill accumulates gradually through deliberate effort. He encourages resilience in the face of setbacks and urges continuous learning through reading and measured experimentation. The final emphasis is on steady, workmanlike habits that convert intention into pages and pages into publication. By uniting craft, routine, and professional conduct, How to Become a Writer offers a practical roadmap from beginner’s desire to sustained, productive authorship.

Historical Context

Arnold Bennett’s manual emerged at the turn of the twentieth century, framed by late Victorian and early Edwardian Britain. Its practical counsel assumes London as the epicenter of English publishing, with Fleet Street’s newspapers and Paternoster Row’s book trade setting professional standards, rates, and rhythms. Yet the work also bears the stamp of Bennett’s origins in the industrial Potteries of North Staffordshire, where disciplined labor and social mobility were daily preoccupations. The setting, then, is both metropolitan and provincial: a rapidly urbanizing nation linked by railways, the General Post Office, and telegraph lines, in which a widening reading public and an expanding periodical press created unprecedented markets for ambitious writers.

The Education Acts transformed the British reading public. The Elementary Education Act of 1870 initiated state-supported schooling; the 1880 Act made attendance compulsory; and the 1891 Act introduced free elementary education. The 1902 Balfour Act reorganized secondary and technical instruction under local education authorities. By the 1911 census, near-universal literacy was evident, with over 95 percent of adults able to sign marriage registers, a common proxy. The Public Libraries Acts (1850, extended 1855) and the wave of Carnegie-funded libraries after 1883 endowed towns with free reading rooms. Bennett’s book presumes this democratized literacy: it treats authorship as a trade open to the educated classes, advising readers how to convert mass literacy into steady markets and professional routines.

The press revolution known as New Journalism reshaped opportunity. W. T. Stead’s campaigns at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s, followed by Alfred Harmsworth’s halfpenny Daily Mail (founded 1896, reaching about one million circulation by 1902), created vast demand for concise, vivid copy. Illustrated monthlies such as The Strand Magazine (launched 1891, early circulation c. 300,000) and Pearson’s Magazine (1896) multiplied outlets for serial fiction and features. Bennett moved to London in 1889 and served as assistant editor of Woman from 1893 to 1900, learning deadlines, word lengths, and the economics of space. How to Become a Writer distills those newsroom and magazine-floor disciplines, urging adaptability to column inches, editorial timetables, and audience tastes forged by the new mass press.

The collapse of the three-decker novel in the mid-1890s altered the business of authorship. Dominant circulating libraries—Mudie’s Select Library (founded 1842) and W. H. Smith’s—abandoned the costly triple-volume format around 1894, accelerating a shift to one-volume six-shilling editions. The Publishers’ Association’s Net Book Agreement (1900) fixed retail prices, stabilizing margins for booksellers while shaping royalty structures. These changes compressed narratives, encouraged serialization, and normalized shorter books. Bennett’s guidance on planning lengths, negotiating serial versus book rights, and writing to the market reflects this reconfiguration. His emphasis on contracts, advances, and the arithmetic of copy derives from the era’s transition from library-controlled fiction to a broader, price-protected retail book trade.

Authorship professionalized through institutions and law. The Society of Authors, founded in 1884 by Walter Besant, advocated standard contracts, fair royalties, and collective bargaining; its journal, The Author, diffused best practices. Internationally, the Berne Convention of 1886 established cross-border copyright protection; Britain adhered in 1887, and the Copyright Act of 1911 consolidated domestic law to life plus fifty years. Across the Atlantic, the U.S. International Copyright Act of 1891 created protections conditioned by the manufacturing clause, complicating transatlantic rights. Bennett’s businesslike maxims mirror this legal and institutional landscape: he counsels vigilance over translation, colonial, and American rights, and insists that a writer’s craft must be paired with the contractual literacy these reforms made meaningful.

Industrialization and urbanization shaped Bennett’s ethos. The North Staffordshire Potteries—Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Longton, Tunstall, and Fenton—employed tens of thousands in ceramics; in 1910 they federated as the county borough of Stoke-on-Trent. London, whose population exceeded 4.5 million by 1901, offered clerical posts, editorial rooms, and literary agencies connected by suburban rail and the fast post. Bennett’s own path from provincial clerk to metropolitan editor epitomized the period’s channels of mobility. In the book, writing is framed as disciplined work within an industrial economy: keep hours, master tools, meet quotas, and ship copy. The advice assumes the timetables and efficiencies of factory and office applied to the commerce of words.

The expansion of women’s work and public voice is a salient social backdrop. Legal and civic reforms—such as the Local Government Act of 1894, which allowed women to vote in local elections and serve on councils—expanded women’s public roles, while growing clerical and teaching sectors opened waged employment. The suffrage movement intensified after 1903 with the WSPU. A burgeoning women’s press, including weeklies and service magazines, sought contributors. Bennett edited Woman in the 1890s and published Journalism for Women in 1898, offering pragmatic routes into reporting and features. How to Become a Writer inherits that inclusiveness, addressing female and male aspirants alike and grounding its counsel in the concrete commissions available in the women’s and household periodical markets.

By demystifying authorship as organized labor within a regulated marketplace, the book serves as a critique of the class gatekeeping and informal patronage that had long governed literary opportunity. It exposes monopolistic pressures—from circulating libraries to price maintenance—and urges writers to counter them with contractual knowledge and collective norms. It treats mass education and cheap newspapers as instruments of social leveling, yet insists that these gains require professional discipline to become livelihoods. The subtext is political: talent should not be stranded by birth or address outside London; fair copyright and transparent terms are matters of justice. In elevating craft plus rights, Bennett indicts the era’s inequities while charting practical emancipation.

How to Become a Writer

How to Become an Author

Chapter I The Literary Career

Divisions of literature.

In the year 1902 there were published 1743 volumes of fiction, 504 educational works, 480 historical and biographical works, 567 volumes of theology and sermons, 463 political and economical works, and 227 books of criticism and belles-lettres. These were the principal divisions of the grand army of 5839 new books issued during the year, and it will be seen that fiction is handsomely entitled to the first place. And the position of fiction is even loftier than appears from the above figures; for, with the exception of a few school-books which enjoy a popularity far exceeding all other popularities, and a few theological works, no class of book can claim as high a circulation per volume as the novel. More writers are engaged in fiction than in any other branch of literature, and their remuneration is better and perhaps surer than can be obtained in other literary markets. In esteem, influence, renown, and notoriety the novelists are also paramount.

Therefore in the present volume it will be proper for me to deal chiefly with the art and craft of fiction. For practical purposes I shall simply cut the whole of literature into two parts, fictional and non-fictional; and under the latter head I shall perforce crowd together the sublime and reverend muses of poetry, history, biography, theology, economy—everything, in short, that is not prose-fiction, save only plays; having regard to the extraordinary financial and artistic condition of the British stage and the British playwright at the dawn of the twentieth century, I propose to discuss the great “How” of the drama in a separate chapter unrelated to the general scheme of the book. As for journalism, though a journalist is not usually held to rank as an author, it is a. fact that very many, if not most, authors begin by being journalists. Accordingly I shall begin with the subject of journalism.

Two Branches of Journalism: The Mechanical.

There are two branches of journalism, and it is necessary to distinguish sharply between them. They may be called the literary branch and the mechanical branch. To take the latter first, it is mainly the concern of reporters, of all sorts, and of sub-editors. It is that part of the executive side of journalism which can be carried out with the least expenditure of original brain-power. It consists in reporting —parliament, fashionable weddings, cricket-matches, company meetings, fat-stock shows; and in work of a sub-editorial character—proof-correcting, marshalling and co-ordinating the various items of an issue, cutting or lengthening articles according to need, modifying the tone of articles to coincide with the policy of the paper, and generally seeing that the editor and his brilliant original contributors do not, in the carelessness of genius, make fools of themselves. The sub-editor and the reporter, by reason of highly-developed natural qualifications, sometimes reach a wonderful degree of capacity for their duties, and the sub-editorial chair is often occupied by an individual who obviously has not the slightest intention of remaining in it. But, as a rule, the sub-editor and the reporter are mild and minor personages. Any man of average intelligence can learn how to report verbatim, how to write correct English, how to make incorrect English correct, how to describe neatly and tersely. Sub-editors and reporters are not born; they become so because their fathers or uncles were sub-editors or reporters, or by some other accident, not because instinct irresistibly carries them into the career; they would probably have succeeded equally well in another calling. They enter an office early, by a chance influence or by heredity, and they reach a status similar to that of a solicitor’s managing-clerk. Fame is not for them, though occasionally they achieve a limited renown in professional circles. Their ultimate prospects are not glorious. Nor is their fiscal reward ever likely to be immense. In the provinces you may see the sub-editor or reporter of fifty who has reared a family on three pounds a week and will never earn three pounds ten. In London the very best mechanical posts yield as much as four hundred a year, and infrequently more; but the average salary of a thorough expert would decidedly not exceed two hundred and fifty, while the work performed is laborious, exacting, responsible, and often extremely inconvenient. Consider the case of the sub-editor of an evening paper, who must breakfast at 6 a.m. winter and summer, and of the sub-editor of a morning paper, who never gets to bed before three in the morning. Relatively, a clerk in a good house is better paid than a sub-editor or a reporter.

I shall have nothing more to say about this branch of journalism. Its duties are largely of an official kind and in the nature of routine, and are almost always studied practically in an office. A useful and trustworthy manual of them is Mr. John B. Mackie’s Modem Journalism: a Handbook of Instruction and Counsel for the Young Journalist, published by Crosby, Lockwood & Son, price half-a-crown.

The Literary Branch.

I come now to the higher branch of journalism, that which is connected, more or less remotely, with literature. This branch merges with the lower branch in the person of the “descriptive-reporter,” who may be a genius with the wages of an ambassador, like the late G. W. Steevens, or a mere hack who describes the Lord Mayor’s procession and writes “stalwart emissaries of the law” when he means policemen. It includes, besides the aristocracy of descriptive reporting, reviewers, dramatic and other critics, financial experts, fashion-writers, paragraphists, miscellaneous contributors regular and irregular, assorted leader-writers, assistant editors, and editors; I believe that newspaper proprietors also like to fancy themselves journalists. Very few ornaments of the creative branch of journalism become so by deliberate intention from the beginning. The average creative journalist enters his profession by “drifting” into it; the verb “to drift” is always used in this connection; the natural and proper assumption is that he was swept away on the flood of a powerful instinct. He makes a timid start by what is called “freelancing,” that is, sending an unsolicited contribution to a paper in the hope that it will be accepted and paid for. He continues to shoot out unsolicited contributions in all directions until one is at length taken; then he thinks his fortune is made. In due course he gradually establishes a connection with one or more papers; perhaps he writes a book. On a day he suddenly perceives that an editor actually respects and relies on him; he is asked to “come into the office” sometimes, to do “things,” and at last he gets the offer of an appointment. Lo! he is a full-fledged journalist; yet the intermediate stages leading from his first amateurish aspiring to his achieved position have been so slight, vague, and uncertain, that he can explain them neither to himself nor to others. He has "drifted into journalism.” And let me say here that he has done the right thing. It is always better to enter a newspaper office from towards the top than from towards the bottom. It is, in my opinion, an error of tactics for a youth with a marked bent towards journalism, to join a staff at an early age as a proof-reader, reporter, or assistant sub-editor; he is apt to sink into a groove, to be obsessed by the routine instead of the romance of journalism, and to lose intellectual elasticity.

The creative branch of journalism is proportionately no better paid than the mechanical branch. The highest journalistic post in the kingdom is reputed to be worth three thousand a year, an income at which scores of lawyers, grocers, bishops, music-hall artistes, and novelists would turn up their noses. A thousand a year is a handsome salary for the editor of a first-class organ; some editors of first-class organs receive much less, few receive more. (The London County Council employs eleven officers at a salary of over a thousand a year each, and five at a thousand each.) An assistant editor is worth something less than half an editor, while an advertisement manager is worth an editor and an assistant editor added together. A leader-writer may receive from four hundred to a thousand a year. No man can earn an adequate livelihood as a book-reviewer or a dramatic or musical critic, pure and simple; but a few women by much industry contrive to flourish by fashion - writing alone. The life of a man without a regular appointment who exists as a freelance may be adventurous, but it is scarcely worth living. The rate of pay for journalistic contributions varies from seven and sixpence to two guineas per thousand words; the average is probably under a pound; not a dozen men in London get more than two guineas a thousand for unsigned irregular contributions. A journalist at once brilliant, reliable, industrious, and enterprising, may be absolutely sure of a reasonably good income, provided he keeps clear of editorships and does not identify himself too prominently with any single paper. If he commits either of these indiscretions, his welfare largely depends on the unwillingness of his proprietor to sell his paper. A change of proprietorship usually means a change of editors and of prominent contributors, and there are few more pathetic sights in Fleet Street than the Famous Journalist dismissed through no fault of his own.

On the whole, it cannot be made too clear that journalism is never a gold-mine except for newspaper proprietors, and not always for them. The journalist sells his brains in a weak market Other things being equal, he receives decidedly less than he would receive in any pursuit save those of the graphic arts, sculpture, and music. He must console himself by meditating upon the romance, the publicity, and the influential character of his profession. Whether these intangible things are a sufficient consolation to the able, conscientious man who gives his best for, say, three or four hundred a year and the prospect of a precarious old age, is a question happily beyond the scope of my treatise.

Fiction.

I have made no mention of the natural gifts of universal curiosity, alertness, inextinguishable verve, and vivacious style which are necessary to success in creative journalism, because the aspirant will speedily discover by results whether or not he possesses them. If he fails in the earlier efforts of freelancing, he will learn thereby that he is not a born journalist, and the “drifting” process will automatically cease. For the same reason I need not enter upon an academic discussion of the qualifications proper to a novelist. In practice, nobody plunges blindly into the career of fiction. Long before the would-be novelist has reached the point at which to turn back means ignominious disaster, he will have ascertained with some exactness the exchange value of his qualifications, and will have set his course accordingly. There is the rare case of the beginner who achieves popularity by his first book. This apparently fortunate person will be courted by publishers and flattered by critics, and in the ecstasy of a facile triumph he may be tempted to abandon a sure livelihood “in order to devote himself entirely to fiction.” One sees the phrase occasionally in literary gossip. The temptation should be resisted at all costs. A slowly-built reputation as a, novelist is nearly indestructibl[1q]e; neither time nor decay of talent nor sheer carelessness will quite kill it; your Mudie subscriber, once well won, is the most faithful adherent in the world. But the reputation that springs up like a mushroom is apt to fade like a mushroom; modern instances might easily be cited, and will occur to the student of publishers’ lists. Moreover, it is unquestionable that many writers can produce one striking book and no more. Therefore the beginner in fiction should not allow himself to be dazzled by the success of a first book. The success of a seventh book is a sufficient assurance for the future, but the success of a first book should be followed by the success of two others before the author ventures, in Scott’s phrase, to use fiction as a crutch and not merely as a stick.

Speaking broadly, fiction is a lucrative profession; it cannot compare with stock-broking, or brewing, or practice at the parliamentary bar, but it is tolerably lucrative. Never before, despite the abolition of the three-volume novel, did so many average painstaking novelists earn such respectable incomes as at the present day. And the rewards of the really successful novelist seem to increase year by year. A common course is to begin with short stories for magazines and weeklies. These vary in length from two to six thousand words, and the payment, for unknown authors, varies from half a guinea to three guineas per thousand. The leading English magazines willingly pay fifteen guineas for a five-thousand-word story. But to make a living out of short stories alone is impossible in England. I believe it may be accomplished in America, where at least one magazine is prepared to pay forty dollars per thousand words irrespective of the author’s reputation.

The production of sensational serials is remunerative up to a certain point The halfpenny dailies and the popular penny weeklies will pay from ten shillings to thirty shillings per thousand words; and the newspaper syndicates, who buy to sell again to a number of clients simultaneously, sometimes go as far as two pounds per thousand for an author who has little reputation but who suits them. Thus a man may make a hundred pounds by working hard for a month, with the chance of an extra fifty pounds for book-rights afterwards. A writer who makes a name as a sensational serialist does not often get beyond three pounds per thousand, though the syndicates may be more generous, rising to five or six pounds per thousand. I should doubt whether even the most popular of sensational serialists can obtain more than six pounds per thousand. In this particular market a reputation is less valuable than elsewhere. And it must also be remembered that the sale of sensational serials in book form is seldom remarkable.

The mild domestic novelist who plods steadily along, and whose work is suitable for serial issue, is in a better position than the mere sensation-monger. She—it is often a “she”—may get from three to six pounds per thousand for serial rights as her reputation waxes, and her book-rights may be anything from two hundred to a thousand pounds. I can state with certainty that it is not unusual for a novelist who has never really had an undubitable success, but who has built up a sort of furtive half-reputation, to make a thousand pounds out of a novel, first and last. Such a person can write two novels a year with ease. I have more than once been astonished at the sums received by novelists whom, both in an artistic and a commercial sense, I had regarded as nobodies. I know an instance of a particularly mild and modest novelist who was selling the book-rights of her novels outright for three hundred pounds apiece. One day it occurred to her to demand double that sum, and to her immense surprise the publisher immediately accepted the suggestion. I should estimate that this author can comfortably write a book in three months.

The Really Successful Novelist.

The novelist who once really gets himself talked about, or, in other words, sells at least ten thousand copies of a book, and who is capable of living up to his reputation, soon finds that he is on a bed of roses. For serial rights in England and America he may get fifteen pounds per thousand, making twelve hundred pounds for an eighty-thousand-word novel. For book-rights he will be paid at the rate of about seventy-five pounds per thousand copies of the circulation; so that if his book sells ten thousand copies in England and five thousand copies in America, he receives eleven hundred and twenty-five pounds. Baron Tauchnitz will give from twenty-five to fifty pounds for the continental rights, and the colonial rights are worth something. The grand total for the book will thus be quite two thousand four hundred pounds. This novelist will probably produce three novels in two years. Magazines will pay sixty pounds apiece and upwards for his short stories, and from time to time the stories will be collected and issued in a volume which is good for a few hundred pounds. By writing a hundred and fifty thousand words a year he will make an annual income of three thousand five hundred pounds. His habit will be to write a thousand words a day three days a week, and on each working day he will earn about twenty-five pounds. All which is highly agreeable—but then the man is highly exceptional.

The case of the novelist who has a vogue of the most popular kind, that is to say, whose books reach a circulation of from fifty to a hundred thousand copies, is even more opulent, luxurious, and lofty. The sale of a hundred thousand copies of a six-shilling novel means that the author receives upwards of seven thousand five hundred pounds. The value of the serial rights of a book by such an author is extremely high in many cases, though sometimes it is nothing. There are ten authors in England who can count on receiving at least four thousand pounds for any long novel they choose to write, and there are several who have made, and may again make, twenty thousand pounds from a single book, which is at the rate of about four shillings a word. And seeing that any author who knows his craft can easily —despite statements to the contrary in illustrated interviews and other grandiose manifestations of bombast—compose three thousand words of his very best in a week, the pecuniary rewards of the first-class “boom” should satisfy the most avaricious and exacting.

The Sagacious Mediocrity.

But the average mediocre novelist, too good to excite a mob to admiration, and not good enough to be taken seriously by persons of taste, can have only a polite interest in the foregoing statistics. It remains for me to assure the average mediocre novelist in posse, that, if he minds his task, produces regularly, perseveres in one vein, judiciously compromises between his own ideals and the desires of the public, and conscientiously puts his best workmanship into all he does, he may safely rely on a reasonable return in coin. There are scores of mediocrities who make upwards of five hundred a year from fiction by labour that cannot be called fatiguing, writers who never accomplish anything worthy of the name of art, but who fulfil a harmless and perhaps useful function in our effete civilisation. The novelist, even the mediocrity, works under felicitous conditions. He is tied to no place and no times. He probably writes for three hours a day, five days a week, nine months in the year. He can produce his tale beneath an Italian sky as easily as in the groves of Brixton or Hampstead. No man is his master, and he is dependent on nobody’s goodwill and on nobody’s whim. Only three things can seriously hurt him: a grave failure of health, a European war, and a prolonged strike of bookbinders. The efflux of time will serve but to solidify his reputation, if he uses it well; his income will rise for years, and will remain stable for more years, and though ultimately it must fall it will not fall as fast as once it rose. On the other hand, the novelist who will not study his readers, who presumes on their obtuseness to offer them less than his best, and who lacks stedfastness, may confidently anticipate a decreasing income, no matter what his powers.

Non-Fictional Writing.

The well-known division of authors into those who want to write because they have something to say, and those who merely want to write, is peculiarly applicable to the non-fictional field. To the former class belong the authors of the best histories, biographies, travel books, theological books, and scientific, critical, and technical treatises. The latter class is composed of a heterogeneous crowd of compilers, rearrangers, and general literary middlemen anxious to turn an honest penny. The former class seldom needs advice of an expert nature, for the troubling consciousness of a "message” almost invariably connotes the ability to deliver that message with all needful lucidity and conviction; no one is so sure of achieving the aims of the literary craftsman as the man who has something to say and wishes to say it simply and have done with it. The latter class needs direction, for it has none of its own; and its principal desire is to make money, whereas with the former class the financial side of the work is usually secondary. Many great works of fiction have been accomplished because the authors wanted money, and wanted it badly and in large quantities, but this can be said of extremely few great non-fictional works.