Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

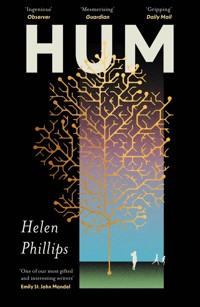

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

'Ingenious and unsettling' Observer 'This sleek ride of a novel further cements Phillips's position as one of our most profound writers of speculative fiction.' New York Times In a hot and gritty city populated by super-intelligent robots called 'Hums', May seeks some reprieve from recent hardships and from her family's addiction to their devices. She splurges on a weekend away at the Botanical Garden - a rare, green refuge in the heart of the city, where forests, streams and animals flourish. But when it becomes clear that the Garden is not the idyll she hoped it would be, and her children come under threat, May is forced to put her trust in a Hum of uncertain motives in order to restore the life of her family. Gripping and unflinching, Hum is about our most cherished human relationships in a world compromised by climate change and dizzying technological revolution, a world with both dystopian and utopian possibilities.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 288

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY HELEN PHILLIPS

The Need

Some Possible Solutions

The Beautiful Bureaucrat

Here Where the Sunbeams Are Green

And Yet They Were Happy

First published in the United States in 2024 by Marysue Rucci Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC, New York.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Helen Phillips, 2024

The moral right of Helen Phillips to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 173 9

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

This book is for my children,Ruth & Neal

Poison is in everything, and no thing is without poison.

The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy.

—PARAELSUS

PART 1

1

The needle inched closer to her eye, and she tried not to flinch. Above her, the hum hovered, immaculate and precise. The steadiness of metal, the peace of a nonbiological body. She had heard of elderly people who, at the end, chose hum company over human company.

The hum paused to dip its needle-finger in antiseptic yet again, then re-extended its arm, a meticulous surgeon. Its labor was calm, deft, as hum labor always was.

Yet the pain grew crisp as the needle moved across her skin toward the edge of her eye. A slender and relentless line of penetration. The numbing gel must be wearing off.

She had twice endured childbirth by imagining her way out of her body, into a forest, the forest of her childhood, a faint path weaving among evergreens. But now the forest of her childhood was receding even in her memory. She needed to picture some other forest, not that particular forest, which was gone, burned.

A forest. She tried to force her mind into a forest.

The hum retracted the needle and, with the fingers of its other hand, carefully reapplied numbing gel to the area around her eyes.

She felt that the hum had read her mind, though she realized it was simply reacting to the mathematically dictated decrease in the gel’s effectiveness over time.

“Please let me know,” the hum said, such a soothing voice, “when it is numb again, May.”

Long before hums existed, she was one of many hired to help refine and deepen the communicative abilities of artificial intelligence. She had taken satisfaction in the process, in the network’s increasing conversational sophistication and nuance, and her small but meaningful role in that progress, until the network exceeded human training and no longer needed their input. But despite all those years of hours spent at her desk, in dialogue with the network, it was very different to be speaking to a hum in person, to have a hum’s actual body near her actual body, each of them taking up a similar amount of space in the room. She had never before been this close to a hum for this length of time, for this intimate a procedure. Back when she still had dental insurance, her dentist proudly introduced his new colleague, a hum with dental tools in place of finger attachments. She was tense the whole twenty minutes, her toes clenched inside her shoes, but her teeth had never felt so fresh.

The hum passed her a plastic cup of water. It was not wearied by the hours of labor. Probably there would be someone else after her, another guinea pig, and another, and another, for the hum could go on and on and on, charging remotely, its grace unyielding, while she frayed more by the minute, her body sweating and growing thirsty. The first time she had seen a hum, standing at a bus stop on a sunny day last year, she had mistaken it for a sculpture, clean silver lines of arms and legs and neck linking oblong head and torso and feet, small spheres at elbow and wrist and knee and ankle joints, polished plastic and brushed aluminum, a gleaming thing.

A week later, she saw another hum on the subway, and soon enough, she saw them on a regular basis, dispensing medications at the pharmacy, taking the kids’ blood pressure at the pediatrician, patrolling the streets alongside human police officers, in such high demand by government institutions and private corporations that the company who had figured out how to so elegantly embody the expansive brain of the network had a waitlist months long.

“Thank you,” she said, accepting the plastic cup of water from the hum.

She sat up in the operating chair to drink the water.

“Do you want to see yourself, May?” the hum said.

“No,” she said, “thank you.”

She would wait until the end, until the alteration was complete.

Sitting up, momentarily free of the needle, she was overwhelmed by dread.

What if Jem was right.

He had cradled her face in his hands in bed last night, his eyes damp in the lamplight, it had been a long time since he had touched her with such care.

“It’s not like I’m going to die,” she had said, closing her eyes.

He moved his fingers over her eyelids, her nose and cheeks.

“Money honey,” she said, opening her eyes, straining for levity.

“Blood money,” he said. “Skin money,” he corrected.

“Rent money,” she corrected, a flash of rage. “Grocery money. Dental bill money.”

He took his hands off her face, turned away from her with a pained sigh, reminding her of other middle-of-the-night conversations that had ended with a pained sigh. Staying up too late, exchanging panic about the children’s futures, what will this planet hold for them by the time they’re our age.

Deliberately, she placed her hands on top of the knot in her stomach.

In exchange for the use of her face she was being given the equivalent of ten months’ worth of her salary at her bread-and-butter job, the solid stabilizing middle-class job that had brought them to the city a decade before, the job that provided certain comforts to which she had become overly, shamefully attached (buying daffodils at the bodega, dropping sixty dollars on dinner out at the diner with the kids for no reason), the job she had lost—because now the network could teach itself, because Nova in HR could only convince May’s boss to keep her on for so long once her irrelevance became irrefutable—three months before. As soon as she was released from this room, she would catch up on the overdue rent. And even after she beelined to the ticket booth, did the outrageous thing, the splurge (but it wasn’t a splurge, not really—more like a reset button for their entire lives), still there would be a big cushion, eight months maybe, or nine if they could be frugal. She would find another job. Never mind that she hadn’t found a job these past three months, the humiliation of her head bobbing on the screen, the unforgiving sheen of her own overhead light on her face, trying to impress someone far away, trying to spin it that it was because she was so excellent at her job that she had lost her job, rendered herself obsolete. She would find another job. Keep the apartment. Have insurance again, or at least be able to pay out of pocket for Lu’s dental care, the relentless cavities, and take Sy back to the specialist to help with his fine-motor skills. Buy groceries. Buy the things the kids kept needing: fluoride rinse, rain boots, a birthday gift for a friend. She would take care of it all. And maybe in the meantime Jem would get more gigs. And gigs he liked better. He could do more each day, five or six rather than three or four, if she did mornings and school drop-offs and school pickups and homework and dinner and bedtime with the kids on her own. That would be fine. She could handle that. Maybe he’d get more art-hanging and furniture-arranging than pest disposal. More weird shopping requests than sewage-backup cleanup. You never knew, with the app. Anyway, his ratings were high, unusually high, though he did fret endlessly over the rare negative ones.

This was a solution. So he shouldn’t give her a hard time about it. No one should give her a hard time about it. Nova shouldn’t give her a hard time about it. Nova shouldn’t have texted, seconds after Jem turned away from her with that pained sigh, Are you sure you’re sure about this?

Though it was Nova who had gotten her going on the whole thing, the two of them grabbing coffee during Nova’s lunch break a couple of months after May was fired. The café had screens at every seat, so she had to peer over two screens to see Nova’s wide-set eyes, beautiful with kindness, her petite body finally round with eight months of pregnancy after three years of attempted self-insemination and two miscarriages. Nova who, nine years before, upon finding out that May was pregnant with Lu, said, “You have that much hope?” Nova, human resources ambassador, pragmatic and courageous, had withstood all the layoffs at the company. Nova knew someone, a friend of a friend, whose start-up had just gotten funding. “It’s a little horrifying though,” Nova said. “I shouldn’t even tell you about it.” But May wanted to be told. Nova ran a finger over the tattoo on her wrist, a subtle geometric design that May had admired from the first moment she met Nova, on the day when Nova processed and fingerprinted her before she started the job, Nova’s confident fingers carefully orienting her hand on the screen. The next day, Nova appeared at the door of her tiny office and asked if she wanted to eat lunch together outside, easily generous, There’s a cement slab between this building and the next that gets a crack of sunshine at noon. Nova had many best friends at work, but May just had Nova. “Adversarial tech,” Nova had said in the café, gazing at her over the screens. “You know, like figuring out how to make it so that cams can’t recognize you? I kind of love that kind of thing. But still, I don’t know if you should do it.” This start-up was drowning in money and seeking faces upon which to test their methods.

However, the effect of the procedure—as the vibrant, slightly sexy scientist had promised her over video chat—would be extremely subtle. This is not radical change. This is barely perceptible change. Certainly not noticeable to acquaintances, and only a bit discernable to your nearest and dearest. Nearest and dearest, he had said that, with pots of cacti and other succulents behind him in a room glowing with windows. Just enough to trick the system, Dr. Haight reassured, just playing a little with the sixty-eight coordinates of your faceprint. Trying out a new nontoxic ink with iridescent pigmentation, not readily visible to the human eye, but tricky for the system. Hard to pin down. Shifts depending on the light in any given space. Your face will become unlearnable. You’ll be incognito. Isn’t that kind of fun?

Wait, so I’ll be untrackable? she’d said.

Well, he said, there’s still your gait, etc. And your phone. But say you didn’t have your phone on you, then you’d be pretty close to invisible, as far as the system is concerned.

And besides, hadn’t she herself—spotting a cam on a lamppost or in a tree, reminded that the air around her was abuzz with data—sometimes had the urge to hide her face or peel it off, to do the same to the faces of her children?

She passed the plastic cup of water back to the hum.

Yeah ok it’s so much $$$$, Nova had texted, but it’s your $face$

I can find more gigs, insomniac Jem had promised insomniac May.

“Is it numb again, May?” the hum inquired, though presumably it already knew that the gel was entering its period of effectiveness.

“It’s numb,” she said, reclining.

The hum’s torso screen had dimmed and muted at some point along the way, but as the hum reached over her to begin the most delicate task of all—the eyelids—the screen brightened and the volume rose, and the breaking news was right in her face: a group of masked people had stormed the offices of a media company, holding their phones out in front of them. Streaming on the screens of the masked people’s phones: live feeds of the journalists’ children playing at playgrounds, boarding school buses, going to gymnastics class. There was an interview with a hyperventilating journalist who had snuck out via the fire escape, but after fifteen seconds the journalist vanished from the frame; she had to get to her son.

“Your eyes must be dry for this part of the procedure,” the hum said, “so I will wait until they are dry, May.”

“It’s just—” she said.

“I understand, May,” the hum said, tilting the smooth oval of its head toward her, the oversized eyes on its face screen gazing at her with what felt like empathy.

The hum switched to a talk show, where the hum who had created the lyrics for the hit pop song “Rake” was being interviewed.

“. . . accounts for the success of ‘Rake’ compared to other songs you’ve generated?” the interviewer was asking the hum.

“Please widen your eyes as much as possible, May,” the hum said, readjusting the needle depth.

The diminutive hum height of four-feet-eleven inches seemed particularly diminutive in the large chair across from the interviewer, a broad man with a loud voice.

The hum placed the needle at the corner of her eye.

“Please widen your eyes, May,” the hum reminded her.

“. . . because who needs a soul to compose a soulful song, am I right?” the interviewer said, pleased with his question.

The needle buzzed along her eyelid, a dull hurt that increased by the moment. The numbing gel was already wearing off again, or was perhaps of limited utility when it came to the eyelid itself.

She could hardly bear this tender pain shooting through her, both inside and out, her eyelids and her memories, that overlit office where she had spent so many years of her life, accepting and rejecting different phrases proposed by the network, trying to articulate in simple language why one metaphor worked while another was gibberish, why one expression of sympathy was appropriate while another was offensive.

“. . . my iteration,” the hum on the screen was saying, “my serial number, my specific arrangement of atoms, that has produced the work in question, Dustin. But every creative hum act is predicated on the creative acts of all other—”

The torso screen changed abruptly to a popular show about miniature dogs.

“Hey,” she said.

“Yes, May?”

“Go back to that interview.” And then, an afterthought: “Please.”

But the hum did not go back.

“The interview,” she repeated.

Still the hum did not go back.

“Please do not move, May.” The hum’s tone was as kind as ever. It ran the needle along the lower lid of her right eye. “This requires utmost precision, May.”

It was common knowledge that hums were designed to obey human requests. To do no harm to humans. Yet this not-small, dexterous hum who had just defied her instruction was manipulating a needle within a millimeter of her eyeball.

She held her breath.

After a moment, the hum lifted the needle.

“That interview was causing you to become tense, May,” the hum said. “So I had to change it. You seem to be in pain, May.”

At first she heard this as a judgment about her emotional state, but then the hum reached over to apply more of the numbing gel.

“Please return to the interview,” she said.

The hum manifested the interview. The interviewer was reaching his large hand out to shake the hum’s slim hand.

“It’s over,” she said, disappointed.

The hum muted and dimmed the torso screen. Her words—It’s over—endured in the room for many minutes, their spell unbroken by any new conversation.

The numbing gel worked its magic, and she sacrificed herself to the hum’s methodical ministrations, half dozing under the needle for some period of time. Her daze was interrupted by the ding of her phone, in her bag on the hook by the door.

Jem, surely, asking how everything had gone.

Knowing that his text awaited her made her newly impatient with the procedure. She wanted to be out of this chair, reunited with her phone, with all the notifications she had missed these past couple of hours. And she had to get to the ticket booth before it closed. Her dozy state receded, replaced by restlessness.

“Are you almost done?” she said to the hum.

“We are almost done, May,” the hum replied.

She could request therapy mode. Nova had tried hum therapy before and claimed to get something out of it. Said it wasn’t so different from therapy with a human. A little strange, at first, but once you got used to it, there was that same feeling of being listened to. And, cheaper. May, though, had no idea how she’d reply to the standard starter questions at this particular moment: What are you feeling? Where do you feel it in your body?

She could request music. But the thought of choosing a type of music, much less an artist, overwhelmed her.

Birdsong, she thought, a lightbulb.

“Could you live stream birdsong?” she said.

“Tropical or forest, May?” the hum said.

She thought of the forest of her childhood. And of her parents, installed—after the fires, the scant insurance payments—in a sedate condominium on a perfectly paved cul-de-sac in a suburban subdivision thirty miles away from the burned forest, where they now tried to live an extraordinarily quiet life, apart from the world, off the internet, spending more than they should on birdseed in an attempt to lure birds to their small deck.

“Forest,” she said. Those paths she had walked daily from the time she could walk until she was eighteen years old. She hadn’t known the last time was the last time. “Rocky Mountains.”

The room filled with birdsong that was traveling, instant by instant, almost two thousand miles to arrive at her ear canals. The birdsong had a physiological effect on her, aching delight, her eardrums straining to hear all the layers.

“The number of birds in the northern part of the continent has declined by three billion, or twenty-nine percent, over the past fifty years, May,” the hum said.

“Stop,” she said.

“My apologies, May. This live stream is sponsored by the Society for the Preservation of Wildlife.”

The needle continued its journey around her left eye. The birds continued to sing. As the numbing gel wore off, she became acutely aware of the bright line of sheer pain moving slowly across her eyelid. For once, the hum did not seem attuned to her discomfort.

She was about to say something when the hum withdrew the needle and spoke: “We are done, May.”

The hum hinged forward at the hips so she could look up at her face on the torso screen.

It took a jolt of courage, hands in fists, for her to meet her own gaze.

Did she look different? Or did she only look different because she was expecting to look different?

The differences were subtle, even more subtle than she had anticipated, and her first reaction was relief—just faint shifts in shading, minuscule alterations to the known topography, her features wavering a bit between familiarity and unfamiliarity, the way she might look in a picture taken from a strange angle.

Entranced, she stared at herself, trying to understand her face. She couldn’t put her finger on what had changed in these intervening hours. All the minute deviatWas directions added up to some sort of transformation, undeniable but also undetectable.

What would Jem say.

“Beautiful, May,” the hum said. She sensed that the hum was not declaring her beautiful but rather was reacting to its own handiwork. “This will present an interesting challenge for the system.”

Her face felt sore, as though badly sunburned.

“It will feel raw for a few days, May,” the hum said. It placed its metal digits on her forehead, the coolness a balm.

Then the hum opened a drawer at the base of the operating chair and withdrew a gauzy gray scarf.

“Allow me, May,” the hum said, gingerly wrapping the fabric around the lower half of her face. “This will protect you while you heal. Certain facial expressions may strain you for a week or so. I input two prescriptions for you at the pharmacy down the street, an oral pain medication as well as a topical antibacterial cream. Do you want them delivered to your home today?”

“I’ll just pick them up.”

“I can arrange for them to be delivered to your home, May.”

“I can pick them up.” She wondered how much they would cost. She had lost her prescription insurance when she lost her job. “And, the—compensation?”

“Was direct-deposited into your account three minutes ago, May.”

She got up off the operating chair. Her legs, she discovered, unsteady.

“There is another rejuvenating face crème that might be of help to you. Rosehip and cucumber. Would you like me to order it for you now, May?”

“You mean another prescription?”

“Not exactly,” the hum said, “but it does have anti-aging properties. Do you approve this transaction, May?”

She kicked herself for not noticing when the hum switched into advertising. She had felt, after being enwrapped in the hum’s attentive care for these hours, after the odder moments in their conversation, a certain affinity with this hum.

“No,” she said.

“Did you know that people can tell how old a woman is by the way her hands look, even if she is otherwise well-preserved?” the hum said. “Could I interest you in a hand lotion tailored to your age group, May?”

“No,” she said, though her hands had in fact been chapped lately. Though the hum, denied, took on a slight wounded quality. She stepped toward the hook, removed her bag. “No thank you.”

“Those jeans would look better with slouchy boots, May,” the hum said.

She was still saying “No thank you” as she exited into the hallway, the metal door closing behind her, the hum offering her something else. She dug around in her bag for her phone, and couldn’t find it, and kept digging. When at last her fingers located it, she seized it, desperate to read Jem’s text.

You’ve been selected to try our new Premier Surprise Sweets service!

2

She stood on the sidewalk outside the medical complex and tapped the link in the overdue rent warning email. Another tap, and another, and rent plus interest, paid. Then, another tap to submit the grocery order she had prepared the day before. The food would reach their home before dinner. She smiled. The smile strained her skin.

She began a text to Jem, wishing he had written to her.

I don’t feel disfigured, she wrote.

She deleted the words.

Paid! she wrote instead, and sent it.

Her prescriptions, her phone informed her, were ready for pickup. The pharmacy in question was a block and a half away. She could spy its red-and-blue sign from here.

She dropped her phone into her bag and began to walk. The smell of exhaust. The colorless buildings of a piece with the colorless pavement of a piece with the colorless sky. Even the trees in their squares of dirt, even the blowing bits of litter, were drained of color.

Crossing the single street that lay between her and the pharmacy, she glanced up and saw, above the walk signal, a cam.

A fist-punch of a laugh shot out of her.

Inside the store, she hurried to the pharmacy counter in the back, hungry for relief. The pharmacy was empty aside from an elderly man requesting a litany of prescriptions, some of which weren’t yet approved for refill, as a hum was politely trying to explain over the old man’s highpitched declarations that of course they were approved for refill, he had been taking them for years.

As she waited, she heard familiar chords coming through a speaker mounted on the ceiling. A favorite song of hers from when she was a teenager, just a guitar and a voice, a melody at once catchy and tender, a goodbye song. The volume was low, and she strained to catch a lyric or two, the particular magic it held for her diluted by the fluorescence of the pharmacy.

“I understand your frustration,” the hum said, “and I am confident that I can help you resolve these issues, Matthew.”

“I need a person,” Matthew said.

Her face throbbed. She turned to stroll down the nearest aisle—makeup—while they sorted it out. Speed-walking down the aisle toward the pharmacy counter came a human employee, “FREY,” looking at once weary and overzealous.

“Your prescriptions aren’t approved for refill yet,” Frey explained brightly.

“Yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah,” Matthew said.

Makeup. Not that she’d dare put anything on her face anytime soon. Halfway down the aisle, she came to a display of beeswax lip balms. Cardamom, lavender, eucalyptus, lemon rind, bergamot. Expensive, though. Extravagant. She ran her fingers over the bamboo tubes. But she had already selected her indulgence for the day. For the month, the year. She listened to the distorted croon of the song she once loved, sitting on a park bench splitting earbuds with someone, underage with vodka in a plastic water bottle.

She turned the corner, into the aisle of school supplies. So many things it would be fun to give them. Things that would make them happy. A pack of six rolls of polka-dot tape for Sy. Forty-eight colored pencils for Lu. Rhinestone stickers. Metallic markers. Glitter glue. She shouldn’t linger.

Matthew and Frey were gone when she returned to the pharmacy counter. The hum scanned her face.

The scan failed, a red error screen flashing before her.

Though of course she knew the scan would fail, was supposed to fail, still it jarred her, a jolt of panic through her body.

“Can you please fully remove your face covering and I will try again?” the hum said, unable to personalize the question with her name.

“Let’s just do fingerprint,” she said, forcing nonchalance into her voice.

The hum manifested the fingerprint option, and she lined her hand up with the silhouette of the hand on the torso screen. It always felt like a slight violation, undeservedly intimate, to touch a hum there, even though she had done it plenty of times. To order a drink at a noisy bar. To verify the kids at the pediatrician.

The torso glowed green with recognition.

“Two prescriptions are ready for you,” the hum said. “Do you approve this transaction, May Webb?”

“I approve.” For the first time in three months, her stomach didn’t tighten as she said those words.

“Your prescriptions are arriving, May,” the hum said. Two bags glided down the conveyer belt toward her. “Did you know that people can tell how old a woman is by the way her hands look, even if she is otherwise well-preserved? Could I interest you in a hand lotion tailored to your age group, May?”

“No thank you.”

“Did you know that we offer beeswax lip balm in five all-natural flavors, May?”

She turned away from the counter—no thank you no thank you—and walked down the drinks aisle, the refrigerated buzz. A craving overtook her. Not a craving for anything in particular; just the realization that she wanted to buy something to drink, to consume. She considered many different colorful options, unable to settle on anything.

Her phone dinged, and she grabbed it, wondering what he’d written back to her. How excited are you for your new Premier Surprise Sweets service!?!

She opened the glass door and pulled out a wild cherry seltzer. She and Jem used to buy wild cherry seltzers on Sunday afternoons in the summertime, back before the kids were born. They’d put the seltzers in the freezer for half an hour. Lie on the floor of their scarcely furnished apartment in the overwhelming heat. A droplet of cold seltzer in her belly button.

Her pain swelled, demanded attention. She paid for the seltzer with her fingerprint at the self-service checkout by the exit and rushed outside. Immediately she missed the air-conditioning. She stood in front of the store, struggling to penetrate the layers of packaging encasing the topical cream: the staples, the paper bag, the plastic bag, the plastic wrapping, the box, the tape, the puncture top. Finally there was a caterpillar of lotion on her index finger. She spread it along her forehead, her cheeks, beneath her eyes, the drug disseminating a numbing calm across her skin. Then she extricated a pain pill from the other pharmacy bag.

She twisted the top off the wild cherry seltzer, pain pill dissolving into the fizz of seltzer in her mouth. How good things felt, sometimes: the cream on her face, the sizzle in her throat.

She drank deep of the seltzer before noticing a clear sticker on the bottle. It blended so well into the label that she could not tell whether it was part of the packaging or sabotage of the packaging: Five hundred million plastic bottles are discarded in your city each year! read the crimson lettering.

She dropped the plastic bottle to the bottom of her bag.

3

The subway was six blocks away. The booth for discounted last-minute tickets was three stops away on the subway. The booth would close in less than forty-five minutes. She could vee. She could afford to vee, now. But given the amount of money she was about to spend, she should probably take the train.

Waiting to cross the street, she watched a pigeon land on the roof of a van stopped at the light. The bird stood on the van, serene. When the light changed and the van moved, the bird panicked and flapped, shocked.

There was a donut shop by the entrance to the subway station. In the dull cast of the day, the donuts in the window glowed. She paused, noticed her hunger. To think that humans, once prey in the wild, had arrived at this. These glazes and sprinkles.

The reflection of her face.

The door of the shop was propped open to the bland, humid day. A barista called out, “Bagel with butter?” And then, a moment later, plaintively, “Bagel with butter?”

As she stepped across the threshold, her phone dinged. Jem.

Air Quality Warning issued in your area from now until 10 p.m.

The donuts in the window, she realized, were fakes; the real donuts were stored in metal bins behind the counter.

She was wasting her time. She hurried out of the donut shop without buying anything, half ran to the subway entrance and descended the stairs.

Passing through the turnstile she spotted a cam, its single attentive eye trained down on her face, and something flickered within her, a lightness, a light-headedness.

The train would come in three minutes. She couldn’t hold still. Her body quivering. She paced the platform, giddy, ghostly, her feet not quite solid on the concrete.

A moist, unclean wind heralded the train’s arrival. She looped the gauze scarf around to protect more of her face.

On the screens in the train, an ad for a sixty-four-date hologram tour with a popular singer who had been dead for twenty-seven years.

A woman in New Zealand had been arrested for going into grocery stores and hiding needles inside strawberries.

A music video of a teenager with gray hair against a gray background, pulling at their face with jerky motions.

A pair of high school girls in Florence, Italy, had been caught on cam stealing all the good-luck coins tossed into a sixteenth-century fountain, vandalizing with golden spray paint the sculpture of Bacchus, taking off their clothes, kissing in the water. There was footage, mesmerizing footage, largely obscured by night—their naked backs, the splashing water, the paint glistening on the marble. Additional cams had identified them hours later, entering a Catholic school in uniform.

According to a new survey, more humans had experienced intense negative emotions in the past calendar year than at any other time in recorded history.

May forced her attention away from the screens. Most of the people in the car—an old woman with a bag of clementines on her lap, a young man with a violin case, a trio of teenagers, a toddler in a stroller—were earbudded and absorbed in phones. A hum stood at rest in the middle of the car, requiring neither seat nor pole, perfectly balanced on its oblong feet, meditative in appearance.

Strange, that now no stranger could snap a picture of her with their phone and immediately know most everything about her.