9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

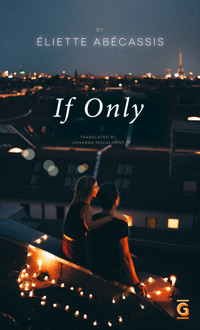

- Herausgeber: Grand Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Amélie and Vincent meet as students at the Sorbonne at the end of the 1980s. It's love at first sight for both, but neither dares confess their feelings to the other. They agree to meet again, but Amélie is late. And in those few minutes, it's not just a date she misses out on, but her entire life. Vincent and Amélie get swept up by life as it carries them toward fates they no longer control, jobs they didn't choose, marriages and relationships that become rocky. Life that takes them down paths, through doors, into hallways, for ten, twenty, or thirty years… It is the story of two lives in parallel across the decades, the story of their relationships and careers, the story of chance encounters that bring them together again and again. Will chance give them the opportunity to get together?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Éliette Abécassis

If only

Translated from the French by Johanna McCalmont

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are from the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

W1-Media, Inc.

Grand Books

Stamford, CT, USA

Copyright © 2023 by W1-Media Inc. for this edition

© Éditions Grasset &, Fasquelle, 2020

First English edition published by

W1-Media, Inc. / Grand Books 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronoic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without

the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

The Library of Congress Control Number is available.

English translation copyright © Johanna McCalmont, 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

ISBN978-1-64690-627-7

www.arctis-books.com

To Ilan, my first rendez-vous

1.

A long hallway, Paris, the Sorbonne University, eye contact. There they were, nothing out of the ordinary, standing in the same line outside the secretary’s office. Just two people chatting, making small talk—the kind of interaction that happens countless times in life.

With her dark clothes, bangs, glasses, and a dash of kohl under her eyes, she was the vision of someone who had just emerged from adolescence when she came up the stairs from the first floor with her best friend Clara—who was dressed in red and black and half hidden under a hat twice the size of her head—and three other classmates. All students at the Sorbonne, the small group shared the same outlook on life and a large apartment with several other roommates, including a young man who spoke a language they had yet to identify—Greek, Croatian, or Swiss German perhaps—and who had been living with them for months without anyone really knowing where he’d come from or what he was in fact doing there. Their home in the heart of the Latin Quarter was a sort of squat, but it’s where they held suitably boozy parties, and where, at night, the empty bones of chicken cadavers and half-empty bottles—or possibly the reverse—lay strewn alongside each other. The five students had met while campaigning for the anti-racism NGOSOS Racisme. They had been protesting about the death of Malik Oussekine—killed during the protests against the Devaquet Law that aimed to reform higher education—and that evening they had ended up together, handing out leaflets and fighting, albeit not entirely sure what for, other than the need to quench their thirst for political activism.

With his jacket, white shirt, round glasses, and curly hair, he was a bit of a catch, a bit Parisian, and he had come from Saint-Germain to sign up for economics. He was polite, shy, socialist, and had welcomed Mitterrand’s election. He was with his friend Charles: a serious-looking Corsican with a frown and a knowing smile. The pair had met in a lecture and campaigned against the far right together.

After registration, they all headed to Place de la Sorbonne for a coffee together. The conversation continued, about this and that, about dreams. The young man and young woman eventually introduced themselves to each other. Her name was Amélie, his was Vincent. Her family was from Normandy; she was studying literature and planned to go into teaching. She had brown hair, dark rings under her eyes that looked at the world as though surprised to discover it in color, a delicate frame, a slim silhouette, and a shy smile; still a child, barely a woman. She wondered if he’d give her his phone number, if he’d want to call her, if he liked her as much as she liked him. If it was better to show how she felt, or hide it, or simply say nothing at all. If she was pretty enough, or if she had some kind of flaw that was a turn-off, something about her he didn’t like. Was her nose too big, were her cheekbones too prominent, was her haircut terrible, did she lack that feminine allure? She was impressed by the way he spoke, the strand of hair that fell over his eyes, his handsome face, the intensity of his expression, his warm voice—deep yet soft, refined. His character was strong yet gentle, and he was polite and seemed to have been brought up well, a little distant but pleasant. There was a hint of creativity, like a mild madness. Sometimes he seemed to be elsewhere, a dilettante, a dreamer. He was musical, and playing piano was the thing he enjoyed most.

Later, the group walked through Paris like tourists. They crossed the bridge, went to the Île Saint-Louis, admired the Seine at sunset, sat on the riverbanks, and talked about their lives. Vincent, sitting in the middle of the group, was fascinated. Seeing her like that, opposite him, so strange, shy, and captivating; she seemed both innocent and impish at the same time. He told himself he had met someone interesting, profound, cultivated—someone who seemed to understand him, to whom he would be able to talk. She was both charming and odd, a little sad, like she was lost in the city. Could she be interested in someone like him? She seemed unapproachable. Yet there she was, beside him, and they were chatting.

Dressed in dark clothes and uncomfortable in her own skin no matter what she wore, what she did, or what she said, her shyness and negative self-image often made her express herself in a way that was slightly confusing. Her mother had repeatedly told her, “With looks like yours, my dear, you’ll have to make up for them with intelligence.” Perhaps she intrigued him? She didn’t dare believe it. He was attractive and had a scar on his left cheek, a bit like that guy Robert Hossein in Angélique, cloaked in cologne and surrounded by girls! There was a slight aloofness about him, and he had a way of looking at her that stopped her in her tracks. Charm oozed from his eyes, and in his deep, almost gentle voice, he asked her what she did. She began to stutter, said she studied, tutored to earn money, wrote in her spare time, liked art, painting, sculpture, went running in the Jardin du Luxembourg with her Walkman. And what about him, was he from Paris? Yes, Montmartre, the hill with the vines, a large apartment, parents who ran a store and didn’t understand him at all or his passion: music. As a child, he had had a teacher—a neighbor who taught at the conservatory in the 17th arrondissement—who had lit his passion for the piano.

Amélie had had a rigorous provincial upbringing and led an ordered life. Her school principal father had never let her go out as a teenager. She had never been allowed to go to bars or parties, which her parents called “blasts”—a word from the teenybopper 1960s they hadn’t really experienced themselves—or invite friends of the opposite sex over. She may have been born in 1968, but it felt like the women’s liberation movement hadn’t happened where she had grown up, or even come anywhere near her family home. She had read Simone de Beauvoir, who had become her role model, her ideal, and had sworn to herself that, one day, she would exist in her own right. She took refuge in books, to see herself reflected, to flee reality.

The weather that evening was beautiful, and the city was already sluggishly succumbing to that summer feeling. People strolled along the banks of the river, past the cafes. Old people, young people, children, women, men, lovers. Couples sat on benches. The streets toward the Marais with its bakeries and restaurants selling falafel and shawarma on the streetside were a joyful hustle and bustle.

When the others decided to go home, he suggested going for a coffee. Why not? They had time. They continued chatting as they crossed the bridge, walked around some more, stopped at a stall selling books on the banks of the Seine. For just a few coins, you could pick up romance novels, thrillers, potboilers, sappy novels, stories within stories, stories that were exciting, new, old, futuristic, manuals, essays, books about psychology or philosophy, history books or story books, and even poetry anthologies.

It was a time when people read: in the metro, in the street, at the beach, in bed, in the bath, in the kitchen. People brought books to parks, gardens, swimming pools, waiting rooms, on buses, trains, and planes. They read in armchairs, on sofas, in living rooms, in hotels, in cafés and bars, in towns and villages, in the summer and winter, in the evening and the morning, while eating, before bed, when they got up, with a cup of tea or a glass of wine, beside the fire as the day came to an end. People read everywhere, at any time of the day, at any time of life, to read another story, escape reality or experience it more intensely, understand others, hate them, or simply pass the time. Every Friday evening, Amélie would watch Apostrophes on TV and listen to Bernard Pivot interview authors with a passion. Roland Barthes, Françoise Sagan, Albert Cohen, Truffaut, Jankélévitch, Le Roy Ladurie or Duby, all of them wearing ties, apart from Bernard-Henri Lévi. Vincent preferred Michel Polac who, sitting in a cloud of smoke, would comment on the debates around the magazines Charlie Hebdo, Minute, and Hara-Kiri, while Serge Gainsbourg—wearing his signature sunglasses—would say “shit’” and Pierre Desproges would expound upon athletes’ intelligence to Guy Drut.

The two students talked for a while about what they enjoyed reading, asking each other if they knew various writers. They both found and bought something to their taste. Amélie picked a first edition of Belle du Seigneur, and Vincent chose Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. She selected hers for the notion that passion is not real love, for the setting in a villa in the south of France where the lovers get bored after having loved each other like crazy. He chose his for the text: “And so loving is, for a long time to come and far into life—solitude, a growing and deepening solitude for those who love.”[1] Then they looked at each other. It was time to say goodbye. So he suggested going for a beer on Quai des Grands-Augustins. The drink turned into dinner, and when they decided to go for another beer, everywhere in the city had already closed because it was so late. So they walked to Café des Capucines, on the boulevard with the same name, open all night. And they talked a while longer. About themselves. About their parents, their desires, their hopes, their friends. About the films they liked, Out of Africa, Marathon Man, Barry Lindon. And about music, the Beatles, Queen, and Chopin.

It got even later, and drinks turned into coffees as they shared a few secrets. How his father had hit him when he was a child, right up to the day he had outgrown him by a head and threatened his father in turn. How her parents fought all the time, going as far as throwing plates at each other, yet wouldn’t separate. How they had both been raised with the sole purpose of pleasing their parents, following the laws laid down by their fathers. But she had only one dream: to seize her freedom and become independent. He toed the line because his father still supported him, which meant he could study without having to work. After midnight, he told her about his brother, his older brother who was twenty-seven and sick. She knew a few people who had AIDS as well, and a friend of a friend was waiting for test results because his partner had told him she had gotten it too.

“Do you spend a lot of time caring for him?” she asked.

“I visit him at the hospital every day. It’s intense, exhausting.”

“What does he talk about?” she asked.

“He tells me about his life. The secret one my parents don’t know about. He tells me everything. He talks about all sorts of things we never talked about before he got sick. We’ve never been as close, and I’ve somehow realized I never really knew him before.”

“It must be hard,” she said.

“I do what I can to help him.”

“Do you have any other brothers and sisters?” she asked.

“No. There are just the two of us,” he replied.

“So he’s only got you?”

“He’s got a lot of friends who are around, thankfully. What about you?”

“There are three of us. I’m the middle one,” she said.

“A tricky position.”

“Yes, I struggle to find my place. I feel like I’m an extra. The ugly duckling. That’s what my mother says.”

“What does she say?” he asked.

“That I’m not pretty.”

“You are pretty,” he told her.

“Really?” she asked.