Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

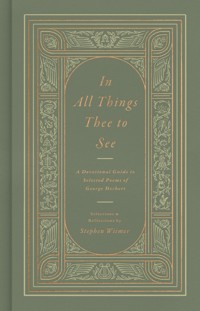

Devotional Invites Readers to Examine and Enjoy One of History's Greatest Spiritual Poets George Herbert, one of the greatest spiritual poets of all time, influenced many of Christianity's most cherished writers including Richard Baxter, Charles Spurgeon, T. S. Eliot, and C. S. Lewis. His works, rich with vivid language, theological insight, and pastoral guidance, expand the reader's capacity to experience and delight in Christ. In this devotional volume, Stephen Witmer presents 40 of George Herbert's most impactful poems, favored for their brevity, accessibility, and relevance to contemporary Christians. With explanations of unfamiliar terms and concepts and brief devotional reflections, Witmer helps readers gain a deeper understanding of each poem and its application. This beautiful volume shepherds readers toward spiritual growth, inviting them not only to engage with Herbert's poetry but also to encounter the God who inspired it. - Beloved Poet: One of the most popular devotional poets of the 17th century and of all time, George Herbert's work is a lasting treasure for believers - Accessible: Featuring approachable poems with helpful explanations, this devotional is made accessible for anyone wanting to reflect deeper on the beauty of Christ - Brief Commentary: Explains unfamiliar words and concepts, and application sections suggest ways the poems can shape and deepen readers' spiritual lives - Useful for Meditation: Thoughtfully crafted to encourage reflection and personal meditation

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 146

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Thank you for downloading this Crossway book.

Sign up for the Crossway Newsletter for updates on special offers, new resources, and exciting global ministry initiatives:

Crossway Newsletter

Or, if you prefer, we would love to connect with you online:

“The poetry of George Herbert holds a hallowed place in the hearts of Christian readers who love devotional poetry. This edition of selected Herbert poems accompanied by pastoral commentary makes Herbert an even greater treasure.”

Leland Ryken, Professor of English Emeritus, Wheaton College

“Herbert’s poetry pulses with praise and pierces with sorrow. It wonders. It beckons. It brings us into the presence of God and deepens our spiritual lives. With a trusted guide like Stephen Witmer, the poems of George Herbert can become friends and companions along the way of life—voices of aid and reflection for all who seek to follow Christ. This book offers forty rich treasures for readers of every kind.”

Abram van Engen, author, Word Made Fresh: An Invitation to Poetry for the Church

“I have never understood why George Herbert is not a household name among Christians. No other major literary author is so evangelical, so Christ-centered, so biblical, so devotional. Stephen Witmer briefly unpacks and applies Herbert’s poetry so that today’s Christians can connect with a fellow believer who can deepen and enrich their faith.”

Gene Edward Veith Jr., Provost Emeritus, Patrick Henry College; author, Reformation Spirituality: The Religion of George Herbert

“George Herbert was a man after God’s own heart. With Stephen Witmer as a reliable guide, this short anthology of Herbert’s best poems offers easy entrance into a remarkable resource for spiritual formation. Through his memorable, beautiful poetry, George Herbert can become one of your soul’s best mentors and truest friends.”

Philip Graham Ryken, President, Wheaton College

In All Things Thee to See

In All Things Thee to See

A Devotional Guide to SelectedPoems of George Herbert

George Herbert

Selections and Reflections by Stephen Witmer

In All Things Thee to See: A Devotional Guide to Selected Poems of George Herbert

© 2026 by Stephen Witmer

Published by Crossway1300 Crescent StreetWheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. Crossway® is a registered trademark in the United States of America.

Cover design: Jordan Singer

First printing 2026

Printed in China

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The ESV text may not be quoted in any publication made available to the public by a Creative Commons license. The ESV may not be translated in whole or in part into any other language.

Scripture quotations marked KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible. Public domain.

All emphases in Scripture quotations have been added by the author of the reflections.

Hardcover ISBN: 979-8-8749-0074-8 ePub ISBN: 979-8-8749-0076-2 PDF ISBN: 979-8-8749-0075-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Herbert, George, 1593-1633 author | Witmer, Stephen E., 1976- editor

Title: In all things thee to see: a devotional guide to selected poems of George Herbert / George Herbert ; edited by Stephen Witmer.

Description: Wheaton : Crossway, 2026. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2025007489 (print) | LCCN 2025007490 (ebook) | ISBN 9798874900748 cloth | ISBN 9798874900755 pdf | ISBN 9798874900762 epub

Subjects: LCSH: Herbert, George, 1593-1633—Appreciation | Christian poetry, English—Early modern, 1500-1700 | LCGFT: Religious poetry

Classification: LCC PR3507.A2 W555 2026 (print) | LCC PR3507.A2 (ebook)

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025007489

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025007490

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

2025-11-17 08:46:07 AM

For my beloved Pepperell Christian Fellowship church family, with deep gratitude and great delight.

A man that looks on glass,

On it may stay his eye;

Or if he pleaseth, through it pass,

And then the heav’n espy.

George Herbert

“The Elixir”

Contents

Introduction

The Altar

The Agony

Redemption

Easter wings

Sin (1)

Affliction (1)

Repentance

Faith

Prayer (1)

The Temper (1)

The Holy Scriptures (1)

Grace

Matins

Evensong

The Windows

Trinity Sunday

Denial

Virtue

The Pearl. Matth. 13.

Antiphon (2)

Mortification

The Dawning

JESU

Dialogue

The Holdfast

The Bag

The Collar

The Call

Joseph’s Coat

The Pulley

The Flower

A True Hymn

The Answer

Bitter-sweet

The Glance

Aaron

The Forerunners

The Elixir

Death

Love (3)

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Notes

Person Index

Scripture Index

Poem Image Gallery

Introduction

Welcome! This volume of forty George Herbert poems is for you. Perhaps you know little to nothing of Herbert and his work. If so, you’re an especially honored guest. In fact, I’ve written with you particularly in mind. I’m eager to guide you to rich poetic and spiritual fare and enjoy it with you. Please, sit and eat. Alternatively, maybe you have savored Herbert for a long time. I’m very glad to hear it. There will be plenty in this book for you to enjoy too. Whatever your prior knowledge and experience, my prayer is that Herbert’s poems will lead you to know Christ more fully and love him more deeply. That’s what they’ve done for me, somewhat to my own surprise.

I was first drawn to Herbert for his prose rather than his poetry. I read him not because I knew him to be a great poet but because I heard he was a good pastor. While writing a book on small-town ministry, I discovered he had written his own rural ministry handbook (The Country Parson) four hundred years ago. Curious, I dipped into a volume of Herbert’s complete works that I had carried across an ocean, then left unread on a shelf for a decade. The Country Parson helped me. Herbert’s life story intrigued me. But it was the poems that began to change me.

They did so by introducing me to new delights and protecting me from old despair. Imagine discovering in adulthood delicious foods you’ve never tasted before. That’s how encountering Herbert’s vibrant, vital language was for me. My life got a little bit richer, my capacity for enjoyment grew a little bit bigger. In “The Glance,” Herbert wrote that he felt “a sugar’d strange delight” when God first looked upon his sinful soul. I didn’t know exactly what that phrase meant, but the sound of “sugar’d” and “strange” together was sweetly pleasing, and the unexpected juxtaposition of those two words was curiously intriguing. Only later would I begin to marvel at Herbert’s skill in using words to evoke the very feelings they described. Initially, I simply felt delight, and expressions such as the “full-ey’d love” of God left me wanting more.

Not only did Herbert’s poems expand my enjoyment of beauty, they also shepherded me through internal struggles. Prone toward sometimes crippling anxiety myself, I found in Herbert an honest, faith-filled fellow struggler. Countless Sunday mornings, I have awakened at 4 a.m., unable to fall back asleep knowing I’d soon be preaching to my congregation. I’d wrestle with despairing thoughts accusing me of not having done enough for struggling church ministries and straggling church members. Would the morning’s sermon fly or flop? In such times, Herbert’s poem “Aaron” became a dear companion, shepherding me toward Christ, “my alone only heart and breast.” Hope would rise as I looked to him, “new drest [dressed]” in Christ’s righteousness rather than my own.

Might Herbert have a similar impact on you? Could he provide fresh joy and wise care for your soul? Could he lead you to more of Christ? That’s my prayer for you.

We’ll begin with a brief introduction to the man and his work, an explanation of why I chose these particular poems, and some guidance on how best to engage with them.1 Then we’ll get to the poems themselves. This volume is all about the poems. My brief comments in the “Savoring the poem” sections will explain unfamiliar words and concepts while guiding you into a deeper enjoyment of the poems. Short application sections (“Shepherded by the poem”) will gesture toward ways in which the poems might shape you. Think of me as the guide showing you the museum, the spotlight operator illumining the actor, or the jeweler displaying the diamond. Or, rather, don’t think of me at all. Forget the jeweler and delight in the diamond.

George Herbert

George Herbert was born in 1593, during the long reign of Queen Elizabeth, who had fully instituted Protestantism in England after her father, Henry VIII, separated from the Catholic Church, creating the Church of England in 1534. It was a time of great religious earnestness and remarkable literary activity. The Act of Uniformity in 1559 had made the Book of Common Prayer (1559) the rule of worship throughout England. Calvinism was the dominant theology of the church. Puritans had emerged within the church, calling for it to remove Catholic ceremonies and practices, and they were willing to be imprisoned for their convictions. William Shakespeare was composing plays and John Donne was writing poems. The King James Bible would be published in 1611.

Part of a wealthy, aristocratic family, George Herbert enjoyed an outstanding education. He distinguished himself as a scholar, became a fellow at the University of Cambridge, and was appointed to the prestigious post of Orator of the University in 1620, delivering orations in Latin for significant academic occasions. That position earned him the attention of King James I, the monarch who ascended to the throne after Elizabeth I died in 1603. Herbert’s star was rising. Then it wasn’t. Life took some unexpected turns. The career it seemed he might enjoy in the king’s court didn’t materialize. Following several uncertain years living with wealthy relatives, he became an Anglican vicar in the village of Bemerton, near Salisbury. He served there in relative obscurity for three years and then died of sickness in 1633, shortly before his fortieth birthday.

And that may have been that. He might easily have been forgotten by all but academic historians. It’s true that he was respected for his polished Latin orations, that he composed some Latin poems and collected many proverbs, and that he wrote The Country Parson. But none of those account for his impact on contemporary readers. His enduring influence rests on a slender volume of about 160 English poems (depending on how you count them) that might well never have seen the light of day.

The Temple

On Herbert’s deathbed, he sent those unpublished poems to his friend Nicholas Ferrar with instructions to burn or print them, as his friend saw fit. Ferrar read them, was deeply moved, and published the volume almost immediately, calling it The Temple. It was an instant and massive success, going through numerous editions in its first decades and establishing Herbert as one of the most popular devotional poets of the seventeenth century. In every generation since, readers have benefited—including Richard Baxter, Charles Spurgeon, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, W. H. Auden, and T. S. Eliot. The anguished William Cowper found solace in Herbert’s poems. C. S. Lewis included The Temple among the ten books that most influenced him.2The philosopher Simone Weil said that during a recitation of Herbert’s poem “Love (III),” Christ himself came down and took possession of her. In our own day, the poems continue to intrigue and attract Christians and non-Christians alike. On February 17, 2014, the British newspaper The Guardian published an article by Miranda Threlfall-Holmes titled “George Herbert: The Man Who Converted Me from Atheism.”3

The Temple has three sections. The first, “The Church-Porch,” consisting of seventy-seven stanzas, is sometimes ingenious, amusing, and helpfully memorable, and it forms an approach to what follows in the middle section. It can be rather preachy and moralizing, and it’s not the main attraction. Neither is the final section, “The Church Militant,” a longish poem that deals with the history of the church and a vision of future judgment upon it. It’s the middle section, “The Church,” that embodies Herbert’s genius and accounts for his enduring influence. These poems have connected deeply with both Christian and non-Christian readers. They’re why Herbert is considered one of the greatest religious poets ever.

The Poems in This Volume

The poems included in this volume are drawn from “The Church” section and account for roughly a quarter of the poems in The Temple. So why these particular poems? The Nobel-prize-winning Irish poet Seamus Heaney once distinguished between poems you admire outside of yourself, like produce in the market, and poems that grow inside you, changing you.4 Years ago, while reading through Herbert’s poems over the course of a summer, I chose fifty I thought might grow inside me. Since then, many of them have taken root and borne good fruit, inviting me into new understandings and experiences of Christ and of myself. For this volume, I’ve drawn from that original list of fifty, added a few others that have captured me since, and favored shorter, accessible poems, particularly those that are theologically rich and fruitfully relevant for Christians today. I hope they’ll change you from the inside out, as they have me.5

How to Read These Poems

How should we read Herbert’s poetry? How can we most profit from his work? I’ve found three approaches particularly helpful.

1. Read Herbert for pleasure. Here’s a simple method for starting with Herbert.

Step 1: Find a poem you enjoy. It doesn’t really matter why you enjoy it (a fresh thought, an arresting phrase, a feeling you get), just that you do.

Step 2: Linger with that one you love. Explore and enjoy it.

Step 3: Repeat steps 1–2.

This method has the merit of reading Herbert the way Herbert himself asks to be read:

Harken unto a Verser, who may chance

Rhyme thee to good, and make a bait of pleasure.

A verse may find him, who a sermon flies,

And turn delight into a sacrifice.

“The Church-Porch,” stanza 1

Herbert meant these poems to please and delight us. The pleasure lures us, and the delight becomes a sacrifice of worship.

T. S. Eliot once wrote,

With the appreciation of Herbert’s poems, as with all poetry, enjoyment is the beginning as well as the end. We must enjoy the poetry before we attempt to penetrate the poet’s mind; we must enjoy it before we understand it, if the attempt to understand it is to be worth the trouble.6

Robert Frost said that a good poem “begins in delight and ends in wisdom.”7 An authority much higher than either Eliot or Frost says, “Great are the works of the Lord, studied by all who delight in them” (Ps. 111:2). Affection spurs inspection. So start by looking for the ones you love. Abram Van Engen offers this freeing counsel for engaging with poetry:

Read just for the joy of it. Do not feel compelled to have deep thoughts or earth-shattering revelations. If such things come, welcome them. But mostly they won’t. . . . When you run into poems you find boring or odd or off-putting, feel free to set them down and try other poems. The great glory of being a full-grown adult is that there is no test—or at least, no test about poetry. You don’t have to read any poem that you’d rather not read. Skip ahead. Pick a different book. Ignore some poems and focus on others. You’re in charge. No one is watching you. The only task is to find a poem that somehow reaches you—something that causes you to respond. Set aside all else.8

This volume contains forty Herbert poems that I love. They’ve wooed me with beauty, wowed me with technical mastery, surprised me with unexpected twists, and soothed me with gospel truth. I hope you’ll agree with me at least once. It takes just one. It begins with pleasure. That’s why the first section heading under each of the poems in this volume is called “Savoring the poem.” Notice, we’re not merely studying it (important as that is) but enjoying it. That’s the place to begin. Enjoyment spurs examination, which leads, in turn, to even greater enjoyment.

2. Read Herbert for pastoral guidance. He was a parish priest. The farmers and manual laborers of Bemerton didn’t walk past his manse and proudly proclaim to their friends that the famous poet lived there, because he wasn’t yet a famous poet. Instead, they knew him as their pastor. He preached on Sundays, catechized them in their homes, and visited the poor of the parish. Biographers tell us he loved his congregation and was loved by them. We know from The Country Parson that he thought deeply about how to shepherd them.

And, importantly, his pastoral calling reached through the parish and into the poems. His poetic aim wasn’t primarily self-expression, the production of great art, or the securing of fame (remember, his English poems were published in print only after his death). Rather, he sought to shepherd souls, to pastor through poetry. We’ve already seen in the first stanza of “The Church-Porch” that his goal for the poems was to “rhyme thee to good.” In his dedication to The Temple, he asks God to “turn their eyes hither, who shall make a gain.” Mark that. He’s writing for our gain.