Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

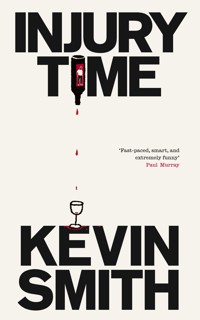

Businessman Fenton Conville has it all sewn up, coasting through life with his mates and his money in a sleepy Northern Irish village. Until, that is, he wakes on his fiftieth birthday to an unexpected solicitor's letter and a shocking allegation that could blow his world apart. In this sharp-eyed comedy of memories, middle age and long-buried mistakes, a privileged entrepreneur feels the chill winds of post-Brexit change in a society struggling to account for its past. Ultimately, Injury Time is a poignant, acerbic look at a man out of sync with the world around him. Kevin Smith's prose is by turns hilarious and incisive, blending satire with a genuine exploration of aging, masculinity, and the slow erosion of certainty. This is a story about dodging bullets, literal and metaphorical, and the painful comedy of life's second half. In the end, Fenton's true struggle is less about money or status than finding relevance and peace as the clock runs down. 'A marvellous cast of characters ... It's hard to know what more could be asked of this winning piece of work.' - Pat Carty, Irish Independent

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 345

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Injury Time

Injury Time

Kevin Smith

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published 2025 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road,

Arbour Hill,

Dublin 7,

Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © Kevin Smith, 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 84351 949 2

eBook ISBN 978 1 84351 950 8

Set in 12.5pt on 17pt Fournier MT Std by Compuscript

Printed in Sweden by ScandBook

In memory of my friend Gerry Dawe And for Dorothea and Olwen

The cloud of infection hangs over the city,

a quick change of wind and it

might spill over the leafy suburbs.

You coasted too long.

– John Hewitt, ‘The Coasters’

All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

– Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

1

Unmanned by his skimpy cotton mini-dress, his thick bare thighs goose-pimpling in the cool air, Fenton Conville took the proffered paper towel, and hesitated – ‘You’re absolutely sure?’

‘Epididymal cyst. Very common.’

‘Benign?’

‘Nothing to worry about.’ The tall, slow-moving sonographer turned his back and leaned over the sink. ‘And if it starts giving trouble, we just insert a needle into –’

With a quack of alarm, Fenton hopped off the bed. ‘There’ll be no trouble.’

A creature, once again, of the light, the heels of his tan brogues ringing out on the marble floor, Fenton strode back along the sun-sharp corridors of the Royal Victoria. Squads of be-scrubbed and be-chinoed medics marched by, pinstriped silverbacks, stethoscopes a-jiggling, orderlies, porters. In all directions, the afflicted were in transit: in wheelchairs, on trolleys, with their tubes and canisters, the faces of the older ones variously stricken or zonked, the younger ones full of bluff or merely numb, each moving along a different, shadow-darkened road. He saw, with darting glances, chalky skin and dank hair, livid scars, bodies wasting inside cheap nightwear and fought the urge to scream.

Pausing at the open door of a side ward, he looked in. Three incredibly old men were propped up in their beds staring at a television screen on the wall, the volume up about as high as it could go. He recognized the film. ‘I’m going to live through this,’ Scarlett was saying, ‘and when it’s all over, I’ll never be hungry again. No, nor any of my folk. If I have to lie, steal, cheat or kill, as God is my witness …’

He hurried on.

Fleeing the gloom of the car park into the sunshine, he began to feel the lightness that infuses the breast of anyone who has ever dodged a bullet. He opened the car window and let the breeze wash the disinfectant whiff from his hair and clothes. He gobbled a handful of Tic Tacs, savouring the rush of menthol through his sinuses. Hospitals definitely weren’t for him, he decided. With a magnanimous wave, he allowed a woman in a wheelchair to cross, then swung onto the road and powered away.

For twenty-seven days, Fenton had been living in fear. Now he was free, gone with the wind across the Queen’s Bridge and on towards the dewy suburbs. The rest of the morning stretched ahead of him, rebooted and refreshed, solid again. It was the first of 183 days before he would be back in the mortal realm he had just left, for reasons he could not have foreseen.

*

‘So. Nearly there. The half-century. The Big Five-O.’ Carolyn, presiding over the granite expanse of the kitchen island, shook her head, eyes bright with macabre wonder. ‘I think the worm is about to turn for you.’

‘Most kind. Very reassuring. Thank you, dear.’

Whatever the worm might be, Fenton thought, it could fuck right off. He opened the paper bag he was holding and released a sausage roll the size, and nearly the weight, of a gold bar. Whistling ‘The Colonel Bogey March’, he shoved his plate into the microwave. He’d had, he reflected, a rough few weeks. First, some anonymous glype, some absolute ganch in the supermarket car park had scobed the side of his car, a three-foot-long gash in the paintwork he feared would cost him, when he got round to taking it to the garage, a vertigo-inducing sum. A couple of days later, his mother had called to tell him his father had slipped in the bath and fractured his femur and that assistance was needed (from Fenton). This, it transpired, included helping the old bugger on and off the lavatory, a task that was to test Fenton’s already tentative sense of filial duty.

Getting him onto the bowl was bad enough – most of his father’s considerable weight was accumulated in his paunch – but heaving him off it while simultaneously trying not to breathe was hotter, dizzier work, and the first time Fenton nearly passed out. On the third occasion, he took the precaution of tying a hand towel, bandito-style, around his face, and this mitigated some but not all of the prevailing mischief.

Fenton’s mother stationed herself at the foot of the stairs while this operation was taking place, ready to swoop in, like some specialist wing of the emergency services, to hose the scene down with Febreze. Snatches of exchange would reach her from above.

‘Dad, please, what did I tell you? Don’t start till I get outside. Holy Jesus …’ (door slamming).

‘Fenton, for God’s sake –’ (muffled) ‘stop making such a song and dance, it’s a perfectly natural –’

‘No, Dad, that’s not natural. Believe me, that is not natural.’

This horrifying situation went on for a full week until the multi-toothed wheels of social care at last engaged and Mihaela and Bogdan, both from Romania, were dispatched each day in time for the 11 a.m. ‘event’. Businesslike and initially cheerful, it seemed to become apparent to the two of them quite quickly that, even by the standards of lowly health-industry work, they had drawn a short straw.

And thirdly (always in threes!) the arrival of the most disturbing and time-consuming worry of all – in the shower, briskly lathering his tackle with pineapple foaming gel – the discovery of the lump. Despite the hot water, he had felt a chill run through him and cold sweat break on his scalp. Further feverish investigation, as he stood dripping on the tiles, brought unmistakable confirmation: a nugget the size of a marrowfat pea on his right gonad.

Top speed then, in his mutilated motor, the next morning to Dr McKenna’s surgery where terror and mortification (‘Just hold your – just keep that out of the way for –’) had vied for dominance in his sleep-starved brain. There ensued a comprehensive run-through of possibilities and options, of which Fenton, in a state of glazed disembodiment, retained only the ramifying phrase: prosthetic testicles.

‘So the next thing will be an ultrasound. I’ll set that up for you,’ said Dr McKenna, groping around his desk and squinting at various scraps of paper. ‘Probably be a couple of weeks before they can fit you in, so in the meantime,’ he raised his muskratty old face and grinned, ‘chin up, what?’

Fenton yanked the overhead cupboard open and located the HP Sauce bottle, which was down to the dregs and made a horrible noise when he squeezed it. He carried his plate to the breakfast island.

‘Listen,’ Carolyn said, wagging a biro and scanning his buff-coloured thatch for signs of grey. ‘While I have you, we need to finalize your guest list. I’m assuming you don’t want the Sinclairs?’

Fenton studied the seething pastry in front of him. The Sinclairs bored him almost to the point of violence (especially the husband, who was a prime example of what Fenton’s brother Artie referred to as a BMO – Broadcast Mode Only – i.e. no receiver) but the truth was, he didn’t much feel like having anybody. His instinct was to skitter under his bed and stay there. Thirty had been a shock, forty a real kick in the teeth, but fifty? Fifty you were out there in the open, on the parched veldt, and those were live rounds in the distance. People he knew personally had died in their fifties. His uncle Toby had more or less exploded at the age of fifty-three – liver, kidneys, ticker, the lot. And Big Titch down at the club, he – well, Christ knows what had happened there, but he couldn’t have been more than fifty-five.

With his fingertips Fenton appraised the contours of his midriff through the tight fabric of his shirt. There was no getting away from it: despite his height and breadth, he was carrying serious beef – not quite Tony Soprano standard yet, but not far off. He tried to recall when he had last not been disappointed at the sight of himself naked in front of the mirror. Ten years? Twenty? On the plus side, at least he’d ditched the fags. What a battle that had been and, if he was honest, continued to be. Three years clean next August and he still felt like a crucial part of his personality had been amputated, regularly dreamed he was smoking, on occasion, having nostrilled fumes from a passing smoker’s cigarette, sensed the nicotine monster twitching and mumbling back to life inside him. Worth it, though, if only so he could climb a flight of stairs without stopping to cough up his spleen.

Unable to hold off any longer, he seized the sausage roll and munched into it, instantly scalding the roof of his mouth. He sucked air in and out very fast. Christ, the stuff was like napalm.

‘Shall I take that as a no?’ Carolyn regarded him over the top of her latest pair of reading glasses, which had blue Perspex frames and put Fenton in mind of the Fairy Godmother from Shrek 2.

‘Yes.’

‘Yes that’s a no?’

‘Yes, I don’t want them.’

‘Okay. So we have Bob and Una, Liam and Eileen, Ciara and Graham, Dawson and – will Dawson be bringing anyone?’

‘I don’t know. I’m not sure where he’s up to.’ Dawson’s wife had died two years previously, and after a short period of mourning, he had embarked on a string of relationships with startlingly unsuitable women of varying ages.

‘M’m.’ Carolyn made ticking noises with her tongue. ‘Newton and Bridget, I’ve invited Stewart from work and his girlfriend, and of the neighbours we have the Hetheringtons, the Bradfords and the McCaffreys. And your parents. Will they be bringing the Dixons?’

‘Oh God, probably.’

‘Right, my parents are heading up to the Glens, so that’s around twenty. Next question, curry or chilli?’

‘Curry … no, chilli.’

‘And the wine and so on, that’s your department, and I’d say, looking at some of the names on this list,’ she tapped it with her pen, ‘you’ll be needing a fair amount.’

Swallowing the last of his lunch, Fenton made a few calculations. It had been a long time since he had hosted so many of this particular crew at once and he was pretty confident that, if anything, their core capacity had increased since the pressure years of small children and mid-career stress, when their drinking sessions, snatched amid cyclones of coloured plastic and pushchair logistics, had been ravenous; borderline hysterical.

He thought: Graham and Bob would require beer, a lot, and later probably vodka or gin; Carolyn and Ciara Sauvignon blanc, extensively; Prosecco and probably vodka for Una and Bridget; the Hetheringtons wine and gin, at least a gallon, plus fancy mixers; his father and old man Dixon whisky (and whiskey); Liz Bradford vodka, a litre minimum; and then there was the barely quantifiable matter of red wine. Dawson, he reckoned, could probably take down a case by himself. His head a-swim with this multifoliate Venn diagram, he rose and moved to the window, where he stood staring out and performing a series of gentle belches.

The upper deck of their house had a view, through a dozen or more mature firs and sycamores, of the broad expanse of Belfast Lough. It was of bold ‘modern’ design, composed, roughly speaking, of a very large rectangular box with two levels (kitchen and living area, four bedrooms) perched on top of a smaller one (study, home gym, TV room, utilities) with an enclosed cobbled courtyard at the rear. It was clad in Siberian larch and embedded with much plate glass.

The site’s original building, which he had managed to have demolished four days ahead of a preservation order, had been constructed in the mid-nineteenth century by a tobacco merchant wanting easy reach of the city and the pleasure of watching his cargo ships sail by from his bedroom window. The neighbouring houses were mainly of the same vintage, many of them still occupied by descendants of the linen barons, ironmasters and whiskey lords who built them. To live here had cost, and was still costing him, a great deal of money.

In good weather he would have opened the sliding doors and stepped out onto the wide balcony. This afternoon a capricious wind was flinging handfuls of cold rain against the glass, more like March than May, and the sea was in frisky form. He watched a loose gang of gulls wheeling and dipping above the slipway at the end of the coastal path where, just out of sight, a small flotilla of yachts and cabin cruisers bobbed and clanked in their moorings. Farther out, swan-white in the central channel, a Stena Line ferry sloped in the ghostly wake of the Titanic towards the open sea, bound for Liverpool or Cairnryan. On the far shore, below the shouldery hills and straggling estates, billows of smoke, as though drawn by a child, emerged from the chimneys of the power station and rolled slowly sideways in the wind.

The plant’s days were numbered, Fenton had read in the Belfast Telegraph: coal-fired, inefficient. Old technology. It had been pumping out plumes of badness as long as he could remember. Part of the landscape. All this had to go, of course, beyond doubt now it seemed: coal, oil, plastic, petrol, diesel (filling his car sometimes he felt shifty, almost criminal), air travel, meat. He had to concede that his imagination faltered when he tried to envisage what was coming, the new order, but this last one, a future without animal protein, induced a sensation that teetered on panic. (The six months of veganism imposed on the household by his daughter the previous year had been a very dark time. He had tried to blot that particular misery from his mind, but impressions flew back to him of dinner-time dread and gastric chaos, of meals that appeared to consist almost entirely of twigs and gravel.) The air-miles factor was also something to be considered, and here he was thinking of long-distance imports dear to him, namely the bosomy Cabernets of the Napa Valley and the silky Pinots of Oregon. Sooner or later, if this followed through, and Brexit, he suspected, was not going to help, he could be reduced to drinking – he shivered – British wine.

It was the speed with which all this had become so frighteningly urgent that he found shocking. It wasn’t as if the evidence hadn’t been there in plain sight – people had been moaning about greenhouse gases and global warming for decades. Unlike the slow drip of data that had eroded his sunbed empire – troublesome stats about melanomas and carcinomas and what have you – and brought it to its knees. The most recent closure had him down to just one salon now, sustained by the last (God bless them) of the death-defiers: the fact-denying, chain-smoking, steroid-munching celebrants of real-time human physicality, in all their peroxided, ultraviolet glory.

And they were the last of them. The new generation, his daughter’s lot, had turned to the fake tan, the self-tanners, the lotions and sprays with names like Ibiza Blush and Crème Brûlée, Tenerife Teak … Somali Warlord. As, indeed, his eldest son’s crew favoured the digital over the analogue cigarette, vaping their popcorn- and apple-crumble- and – God knows – roast-pork-flavoured ‘juices’.

He wiggled with a thumbnail at a fragment of gristle lodged between his molars. Now that he had put the testicle thing behind him, he could return to his main preoccupation: how to shore up his rapidly dwindling income. He wasn’t like some of the folk in the other houses around him, people he knew of, and about, but rarely saw, whose families would be insulated for centuries to come by the riches their great-grandfathers had gouged out of the Americas and the Indies. He was second-generation money. Set up in business by his father, and following in the old man’s entrepreneurial footsteps, he had done very well for himself – this was undeniable – but somewhere along the line, it seemed, he’d gone to sleep.

In the early years he had derived much pleasure, as he brought each new tanning salon on stream, from the exponential bulking of his net worth. By the age of twenty-six he had half-a-dozen shops and three rental units hosing cash into his vaults. His bank statements were a monthly treat. He had a nice bungalow in The Heights and a brand new viper-green Lotus Esprit and was whisking young Carolyn (she was five years his junior) off for weekends in Paris and Barcelona. As he turned thirty, his sunbed chain had doubled and he was upsizing to a detached stone build in The Demesne in readiness for a second child. He was young and wealthy and could only get wealthier.

But as he entered his middle years, he hit a few bumps. A foray into the stock market under the influence of a coked-up, and subsequently struck-off, financial advisor had been close to disastrous, and his feverish decision to encash his rainy-day funds in the midst of the 2008 meltdown, when they had already dropped fifty per cent, still gave him the sweats.

But the big move, the game changer, had been building the house – his Grand Design. The cash burn had been ferocious and had put him in an order of debt he hadn’t encountered before: heavy, leveraged, long-term, uncomfortably invasive. Under the arrangement, the bank had dibs on half his franchise, had the right to call it in, to liquidate ‘if adjudged necessary according to the bank’s own principles of prudent self-interest’, and this it had done – discerning the writing on the wall before Fenton had even looked up from his chicken tikka masala. This had had a grievous impact on his cash cushion.

Out in the bay, following the shoreline, Judge McCoubrey’s sparkling navy-and-white motor yacht surged in the direction of the marina. At the wheel, on the flybridge – Fenton could make out his bright-yellow slicker and shiny bald head – the judge was enthroned, imperious even at this distance, and master of the waves. Once he’d dealt with his cash-crunch, Fenton was thinking, he would have one of those boats for himself. Except even bigger.

He was momentarily distracted by the sight of a string of oystercatchers stooping, pensive professors, along the water’s edge. Oystercatchers? Was it really a case of catching oysters? It wasn’t as if they were jinking around playing hard to get. Did those lads even eat oysters? Fenton did his best thinking while looking at the sea, at the birds, watching them at their frictionless, uncomplaining labour – and now, as the clouds shifted and pencils of sunlight picked out glints and sparkles on the far hills, an idea began to form.

All this. The future. The new dispensation. All that was coming towards him: he could face it (he had no choice). It was coming for everyone. Everyone had to face it. He turned from the window with purpose and, humming a little tune, made for the stairs, his den and the internet. He had research to do.

2

On Saturday morning, Clive and Hazel’s number-one son brought his car to a gravel-spurting halt in the driveway to their house – the house he grew up in – a flaking Victorian villa hidden among the mossy-walled lanes above the village. The earlier rain showers had ceased and a fine mist was clinging to the magenta blooms of the rhododendrons. Fenton glanced again at his watch: 11.19. Better give it another few minutes, he thought, turning the radio up a couple of notches. It was a phone-in. The programme’s host was trying to reason with a man called Ephraim from County Antrim who seemed to be proposing some kind of curfew for homosexuals.

‘Sir, you can’t be serious, this is the twenty-first century. Where have you been living?’

‘Oh, I’m perfectly serious, boy, and I don’t give a hoot what century it is. I live by God’s law and these people, with their –’

At that moment the front door opened and Bogdan appeared at the top of the stone steps in his baby-blue fatigues, scrabbling a cigarette from pack to lips and igniting it in a single motion. He took a robotic succession of hollow-cheeked drags, his gaze fixed on a nearby flowerpot. Fenton allowed himself a moment or two of nostalgia, then clambered out of the car and approached the house, flashing a grin at an unresponsive Bogdan. Inside he found his mother gripping Mihaela by the upper arms and talking in firm, consoling tones. ‘Okay? Do you hear me? It won’t be for ever … Mihaela, look at me.’

Fenton juked past them and down the hall to the kitchen where his father, dressed in pyjama bottoms and a pink golfing jersey, had been installed in his armchair beside the Aga, his gammy leg, in its yellowing cast, propped up on a footstool. He was engrossed in a copy of his favourite magazine, Warmonger, whose cover boasted a special feature on the world’s top-ten tanks.

‘Don’t tell me – Challenger at number one?’ said Fenton, making for the kettle.

‘Leopard 2. Germany.’ His father grunted. ‘Hard to argue. Faster, more agile, longer range. A fearsome beast. Though the Challenger has better armour and its gun is rifled, making for a greater firing distance.’

Fenton popped a teabag into a cup and added hot water, then scrutinized the contents of the battered tartan biscuit caddy. ‘Really?’ he said. His father’s obsession with the fine detail of the military world was pretty much a mystery to him: the blizzards of specifications and half-hour conjectures about the ‘what if’s and the ‘and yet’s of various battles put him into a kind of trance. When they were growing up, the old man had been an agreeable but fleeting and unreadable presence in the lives of Fenton and his younger brother, Artie, devoting himself to commerce and golf, and leaving household business and the imposition of discipline (and much had been required) to his wife. In later years, when he was in full flow about some rout at Anzio or El-Alamein, Fenton occasionally had the sense that he was somehow, belatedly, trying to explain himself.

‘Mind you, you have to respect the Yanks here. The Abrams M1A2, real killing machine, very nippy despite the weight. Of course, they’ve also gone with the smooth-bore cannon –’

‘Mm-hm.’ Fenton rummaged out a Penguin. ‘Listen, Dad, speaking of tanks in the field, I was wondering if I could talk to you about something.’

His father lowered the magazine and peered at his son. ‘Any more of those?’

‘What? Oh. Sure, have this one. Yes, I’m thinking about a new venture.’

‘Really? What kind of venture?’

‘A shop. In the village.’ (‘The village’ was family parlance; it was, in fact, a small town. ‘Town’ was reserved for Belfast.)

‘Really? What kind of shop? Here, open this for me, would you.’

‘There you go … A vape shop.’

‘A vape shop?’

‘Yes.’

‘You mean the weird steam things, with the funny …?’

‘Well, it’s not steam as such, it’s vapour, and yes, it’s getting very popular with the youngsters and people trying to give up smoking. It’s a big growth market. I’ve been looking at the margins and, I have to say, they’re pretty tasty.’

Fenton watched his father’s face attempting to digest this information, the biscuit in his hand unbitten. ‘The thing is,’ Fenton continued quickly, pouring milk into his cup, ‘the tanning business is dead in the water and I have to diversify, and what with one thing and another, I’m a bit overextended at the bank, and I was, uh, wondering if you could lend me some start-up cash, seed money?’

His father was examining the half-peeled Penguin as though it was an exotic fruit he had never seen before. ‘Seed money?’

‘Yes.’ Fenton took a sip of tea. ‘Just until the operation is cash-generative.’

‘Cash-generative. M’m. How much?’

‘Let’s see, I’d need six months’ rent for the premises, outlay for the initial stock. Say fifty grand?’

His father’s lips formed a pantomime O and his eyebrows moved upwards. Fenton didn’t like the look of it.

‘I’m not sure about that, son. I mean, that’s quite a lot –’

‘You’ll get it back.’

‘Oh, no doubt, son. It’s just our money is tied up, locked in, at the moment, funds, trusts for the grandchildren and what have you, and your woman has just booked us on a, well, frankly, ridiculously expensive cruise next year and –’

Just then the woman in question swept into the kitchen in a mode that Fenton and his father both recognized. Each adjusted his expectations.

‘Right, Clive, that’s the last time you have curry. I mean it. Those poor people.’

Clive of India knew better than to protest. ‘Hazel, dear, your son is asking for a loan,’ he said, ‘to open a vape shop.’

‘What? Good morning, Fenton. What’s he talking about? A vape shop? A vape shop?’ (This last in the manner of Lady Bracknell.)

Fenton set down his cup. Through the window behind his mother was a large bush, possibly blackberry, that had been trained over a rusting metal arch. It was badly pruned and seemed to Fenton to be mimicking his mother’s latest hair-do. She was, what, seventy-three, seventy-four? Why did she have Rod Stewart’s hair?

‘Yes, I was just saying to Dad –’

‘A vape shop?’ (Again, Fenton didn’t care for her tone.) ‘And what kind of money are we talking about?’

‘Fifty! He wants fifty K,’ the armchair warrior shrilled.

‘Fifty thousand pounds? Fifty thousand pounds?’

Fenton exhaled. He knew a beaten docket when he heard one. His best policy now, he decided, was to shut down the conversation, divert to a neutral topic such as gardening or grandchildren, make an excuse and leave. What actually happened was that, as if in a horror film, another Fenton – in this case, snarling, fuck-it-pull-the-pin teenage Fenton – came barrelling up from the depths and took charge.

*

Back in his car, breathing heavily and trying to subdue the last of his fifteen-year-old self’s flailing limbs, he reviewed the previous torrid few minutes. Had he really called his mother a selfish old bitch? Goaded his father to ‘grow a pair’? More horribly, had he really questioned, at high pitch, their hanging on to all their cash, given that they would probably die soon?

He had been under strain, he told himself; he was under pressure. But even so. He then reflected, cheeks aflame, on the style with which he had left the kitchen. He hadn’t exactly stormed out: no door had been slammed off its hinges, no threats or insults guldered over his shoulder. He wanted to think it had been a dignified stride, at worst a petulant stomp, but no, he was pretty sure – no, he was certain – he had flounced out.

3

From the window of his office above the furniture showroom, Crawford Wylie (Litigation, Matrimonial, Wills and Powers of Attorney) looked out on High Street and blew again on his coffee, which was black, the milk in the fridge having turned. This discovery had not improved his humour. He disliked having to work at the weekend and would have much preferred to be at home rediscovering the joys of vinyl on his new state-of-the-art carbon-fibre-and-glass turntable (only fifty had been made; it had cost more than a small car).

His immediate view was of a section of shopfronts, including a beauty salon, an undertaker’s and a Chinese takeaway, bookended at the corner, beside the crossroads, by the Coachman’s Inn, with its barley-sugar windows and faux Tudor beams. On the opposite side of the intersection was another pub, The Tipsy Toad, a pharmacy, an antiques shop (though it was mostly repro) and an ‘organic’ deli that specialized in high-density, gluto-hypogenic flapjacks. Just visible in the distance, beyond the rooftops and framed by the arch of the railway bridge, was a splotch of seal-grey sea. The wind, when it gusted up the street, brought a fine mizzle of iodine-scented spray. Down below, the townsfolk were going about their business, as they did every day, from butcher to baker to café to florist and all points in between, stopping from time to time for a bit of banter, a good old gossip.

The solicitor sipped his non-dairy coffee, watching their peregrinations without expression. For nearly twenty years he had been at the service of these people, taking care of their house moves and trust funds, recovering their debts, pursuing their claims for recompense, administering their oaths, witnessing and contesting their wills. They came to him at moments of gravity in their lives and he gave them peace of mind with his iron-clad bonds, deeds and codicils. And how often had he heard behind the jargon and niceties, and read between the lines of legalese, their true earthly motives: spite, greed, revenge? And how many times had he marvelled at the power of gold’s magnetic fields and the haywire dances it led people to perform?

In the end, of course, it was all about the money. If he thought about it too much, it would make him sad: the husbands and wives, the brothers and sisters, the mothers, daughters, fathers, sons – at seething loggerheads forever over a few quid, a half-acre of land, a pair of chipped porcelain spaniels. (But who gets the family Bible?) He wondered sometimes how you were expected to maintain your faith in human nature. His own he knew to be in very poor shape. A tune popped into his head, a song about money – by the Flying somethings, Lizards, was it? – and he hummed it. Were the best things in life free? It depended, he supposed, on what you wanted.

What did Crawford Wylie want? In the beginning his goals were modest, and having just about scraped through every exam he ever sat, despite putting in the hard graft, this was prudent. Through his junior years, racking up countless billable hours for his yacht-owning masters, ‘competent’ was as high an accolade as he could expect. But he’d kept his head down and chipped away, and at the age of twenty-seven, by dint of luck and a tangential family connection, he came under the wing of Rex Bunting, a gent of great charm and fierce integrity, who had returned to his home town after a long career in London and set up a little practice to see out his days. Rex spent most of his time playing golf and flying light aircraft, leaving ‘young Wylie’ to mind the shop. Four years later the old boy crashed his Albatross 190 into a sea stack off the coast of County Clare, and that seemed to be pretty much that.

And yet. Taking over at the widow’s behest, Wylie set about expanding the client base and engaging new associates, eventually drawing from it a tidy income. He married, upsized to a handsome detached house near a golf course, procreated (two girls and a boy) and, by anyone’s standards, fulfilled the bourgeois contract. He drove a luxury German car and had a weekend cottage in the Antrim Glens. He experienced spells of faint, vegetal contentment.

Then, in the middle of his life, he had discerned, with much puzzlement and disquiet, a great emptiness within himself, a void that yawned, as it were, in the face of material enrichment. A voice came whispering to his mind that there must be something more. He turned, as many do, to self-improvement. First, physical fitness: he began running for (or away from – he was never quite sure) his life. He invested heavily in a home gym where he sweated and suffered for several long months in preparation for a marathon which, in the event, saw him staggering towards the finish line in urgent need of paramedical attention.

Next, the esoteric lures of the East: tantric yoga, tai chi, transcendental meditation. He even briefly toyed with Buddhism. This all passed. It turned out money was what he wanted all along. In fact, it became clear that he wanted a lot more of it. As the clock ran down, he found he desired, more than anything, consolidation, depth, surplus. His ageing soul was becoming hungrier, greedier; it agitated for excess of resources – a bigger, plumper cushion. And there was something else he wanted too.

Across the street Marty McCann, re-diagnosed with cancer three months back, had stepped out of The Inn for a smoke. Wylie noted his shocking pallor in the sunlight, his diminished bulk; thought, that’ll be a bit of paperwork before too long. Ye know not the day nor the hour, his granny had been fond of saying, keep watch! And there, going into the charity shop, was Johnny Baird whose mother had left him a million he didn’t even know she had, and what did he do with it? Nada. Tight as a shark’s arse at forty fathoms. Nearly a year getting the probate fees out of him and then only after he had the Fox twins pull the wee chancer over for a chat. Whites of their eyes in this game sometimes.

About to turn away, Wylie caught sight of a familiar figure waiting for the green man at the lights on the corner. Boy, he’d fairly put on the weight (at school he’d been a wiry scrum-half); quite a high colour on him too. Huh. Smiling to himself at the coincidence, Wylie returned to his desk and hoisted the stack of folders he’d been working on to the top of a filing cabinet. Back in his chair, he took a sheet of notepaper from the drawer, uncapped his pen and, with an involuntary twitch of his neck, began to draft a letter.

Dear Mr Conville,

I am writing to inform you of an allegation made against you by my client, that on the night of ...

4

‘Same again?’

‘Better make it a half.’ Fenton pushed his empty glass away. ‘Driving,’ he added, though no one was listening. The upstairs lounge of The Tipsy Toad was in full lunchtime swing. It was warm and just bearably noisy, and after three pints of Pilsener and a square foot of lasagne Fenton was beginning to feel a little steadier.

After the blow-up with his parents, he had gone round to see Wee Davy, his mechanic, who had stood and stared, crouched and squinted, sniffed and clucked, and drummed with his fingers on the car roof for a full minute before quoting him £800 to buff out the scratch. This had prompted quite a bit of swearing from Fenton, followed by an intransigent, and finally menacing, silence from Wee Davy, resulting in Fenton’s rubber-burning departure. Thence to the new off-licence where, having assembled a shanty town of boxes containing several hundred quid’s worth of birthday booze, he was informed (a little offhandedly, he felt) that the off-licence didn’t deliver.

‘There y’are, love. Do you want to pay for the food now as well?’ The barmaid was about twenty, ebony hair scraped vertically into a clenched bun, her skin stained to hi-vis intensity. Her ‘eyebrows’ were large and wedgeshaped, precision drawn and heavily coloured in with what appeared to be black marker pen – what the fuck was going on, thought Fenton: it was like looking at a life-sized emoji.

‘Yeah, why not?’

He swallowed a mouthful of beer. He’d call his parents later and straighten things out. They’d understand. He had no choice though, he realized, but to play the testicle card – use his plum-scare to leverage sympathy. Under his breath he practised a few phrases: I didn’t want to say anything … didn’t want to worry you … been a bit of a strain. Timing and tone were key. You never know – he sniffed – they might even take pity on him and advance the bloody spondulicks. But, even as he thought this, he knew it was too long a shot. So what then? Back to the bank? He couldn’t go back to the bank. Not yet. Wait a minute, perhaps … He straightened himself on the bar stool. In his mind now was an impression of watchful energy, expensive tailoring and Ealing Studios hair: his father-in-law. Cecil McCracken. A semi-retired bookmaker and businessman, Cecil had stacks of cash. Old school, though. He’d want some kind of deal. What was the word? Vig. He’d need his vig. Could be a bit awkward.

‘That’s thirty-eight pounds forty when you’re ready.’

‘Fuck me. Thirty-eight quid? Seriously?’ Groping for his wallet, Fenton gazed again at the human avatar. ‘You sure?’

She nodded. ‘And forty pee.’ She consulted the docket. ‘You had three and a half pints of Pilsener. That’s a premium import, so it is.’

‘And the food?’

‘The lasagne’s fifteen pounds.’

Back outside, Fenton found himself in something of a fugue state. There was a time he could have walked into any one of seven pubs (three had since closed) and had a couple of pints and a tureen of stew for a fiver. He located the wait button with his thumb. Traffic was nosing in both directions, halting every few seconds as someone left a parking space and someone else attempted to shoehorn in. He listened to the quotidian hubbub of the street, took in the swirls and eddies of passing faces, and it seemed, suddenly, that he was on an elaborate filmset among senescent, once-familiar actors. He saw his own school-uniformed ghost – cockatrice quiff and steel-tipped Oxfords – strutting towards him along this very pavement. No time at all ago, and yet … These moments of ache were becoming more frequent, each tiny, half-grasped epiphany gone in the breeze like a breath of diesel.

Across the street a woman was standing outside the pharmacy rummaging in a small leather rucksack with the urgency of all women rootling in a bag. Having located whatever it was, she shouldered the pack and, glancing up, met Fenton’s gaze and held it. For an instant she looked as though she was about to form a word – his name perhaps (or possibly just an expletive) – but, almost as quickly, she seemed to remember something and hurried off. The beeps went and he crossed, pausing to survey her retreating figure: navy puffer jacket, jeans, dark hair tied in a ponytail. There was something about the walk.

Intrigued, he changed course and began to follow her. Someone he didn’t recognize tooted and waved at him from a white SUV and he waved back. Outside the post office the woman was hailed by another female and her male companion, and the three stopped to chat. Fenton turned to feign interest in the window of the nearest shop, which had been until very recently a small art gallery of the kind that sells expensive misshapen pottery and garish acrylics of overweight cats. Now a sign taped to the glass said ‘Prime Retail Space to Let’ and gave the contact details of a local agent. He put his face to the window and peered in at the bare interior. The unit was sandwiched between a coffee shop and an ice-cream parlour, two crucibles of leisure and pleasure – a perfect spot for his new venture! He stabbed the number into his phone.

When he looked up, the woman had gone but, not having any particular urgency in his day, he continued in the same direction. It was a while, it occurred to him, since he had walked the length of the village, more usually taking the bypass in his car, and now he was giving it fresh attention.

The place had lived through a few lean times over the years but only comparatively, not like some spots: there was enough fat in the Avenues and Demesnes and Heights around-about to rule out any sighting of tumbleweed. Many of these people had been trading as far back as he could remember: chemists, florists, grocers passing down to sons and daughters, other businesses changing hands but retaining the family name. Crawley’s here, for instance, still a shoe shop, though Des Crawley, without an heir, was dead and gone. Fenton remembered the man’s haemorrhoidal eyebags behind the Joe 90