Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Telegram Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

On the shores of Lake Como a man and a woman talk about longing and belongingl; a translator finds himself drawn into the personal and political turmoil of the poet he translates; a woman's quiet world is eroded by World War II and the division of her country. Charting the geographies of leave-taking and homecoming, the consolations and rivalries of friendship, adolescent yearnings and maturity's tentative acceptance of longing, these exquisite stories engage with the grand narratives of our time. 'Both disconcerting and alluring...the further the reader travels into Hussein's landscape of erosion, the more potent his capacity to find beauty becomes.' Times Literary Supplement 'Profound but low key; spiritual, but pragmatic; full of longing, but also acceptance.' Independent on Sunday 'Emotionally as well as intellectually charged.' New Statesman 'Hauntingly convincing.' The Daily Telegraph 'Lovely short stories...sharp, bitter, subtle comedy.' The Times 'Fresh, personal and profoundly moving.' Kamila Shamsie, Literary Review 'Superbly written short fiction...the writing is both delicate and powerful: these are very fine stories indeed.' Independent 'A gem-like collection...Aamer Hussein is a consummate stylist...His prose is restrained, precise and yet deeply moving. He is a sensuous writer in whose stories nature acts as a balm on even the most weary of sensibilities.' Moni Mohsin, Literary Review 'Profound, beautiful' Ruth Padel 'Wonderfully evocative and readable' Kate Pullinger

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 159

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Aamer Hussein

Insomnia

TELEGRAM

Contents

Acknowledgments

Nine Postcards from Sanlucar de Barrameda

The Crane Girl

Hibiscus Days: A Story Found in a Drawer

The Book of Maryam

The Angelic Disposition

Insomnia

The Lark

A Note on the Author

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of ‘Hibiscus Days’ and ‘Nine Postcards from Sanlucar ...’ have appeared in Wasafiri. ‘Insomnia’ was first published in Moving Worlds. A slightly shorter version of ‘The Crane Girl’ was published as ‘Tsuru’ in the anthology Leave to Stay (Picador). I’d like to express my thanks to the editors of these publications.

Special thanks in London to Mai, Mimi and Hanan, as always; to Geri for Sanlucar and so much more; in Delhi, to Gagan for Amrita Sher-Gil and Sunday dosas and exchanges about insomnia, and Rana, for midnight drives and conversations.

And wherever they might be at a given moment, to my family, without whom ...

I’d also like to thank the team at Saqi, especially Anna and Becky. And to all the other friends in London and elsewhere – you know who you are – who travelled along with me on the highroads and detours of writing these fictions.

Finally, some writers who inspired me: in Delhi last December, I reread the poems of Majaz, who found his way into a story. In Delhi, too, I discovered the writings of Anis Kidwai through a conversation with Qurratulain Hyder; Kidwai’s distinctive style as an essayist, and her narration of Partition’s events, along with Saliha Abid Husain’s writings in many genres, brought me closer to understanding Muslim intellectual life in the years leading to Partition. And, never far from me when I wrote ‘The Angelic Disposition’, the influence of my maternal great-uncle Rafi Ajmeri (1903–1936), who shares his first name, the grace of his style and the plots of some of his stories with the hero of my fiction.

Aamer Hussein

London, May 2007

Nine Postcards from Sanlucar de Barrameda

1

Before breakfast, I walked back to last night’s perfumed bush. It wasn’t fragrant now: I must have smelt a night flower. We breakfasted beneath an orange tree. By the Alcazar gate a chamber orchestra played the Habanera from Carmen. Only oranges and songs to take away.

We are leaving Sevilla. The bus station is crowded, proletarian. My companion wants water, a ham roll, the Ladies’ loo. I fear we won’t board on time.

A skirmish for seats, but they’re numbered. We leave on schedule: midday on an August Tuesday.

2

On board, a confusing text on my companion’s mobile. We try to calm each other: aren’t we expected in Sanlucar? Is there some misunderstanding? Dun landscapes from the window.

The journey’s shorter than expected. God, the vagaries of making electronic contact. My irritation makes my travelling companion laugh out loud.

I stole the term ‘companion’ from Pavese. In real life friends are all that matter, but ‘friend’ in a narration sounds coy.

Perhaps we laugh together.

3

My Spanish sister – I call her that, she calls me hermanito – is waiting at the little station. We have come to her for her birthday. She drives us to her new house: full of light as homes should be, with airy windows.

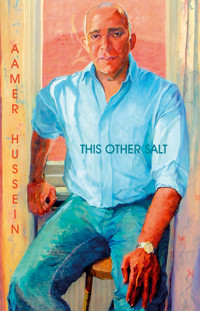

A year ago she painted me, in oils. I’m dressed in blue and larger than life, sitting by a window of her London flat. Behind me there’s a red brick wall. She complained of London’s changing autumn light. Here she paints in her eyrie, in a tower. Her studio overlooks tall palms, jasmine bushes, bright flowers.

Later, with green figs, white peaches, local cheese, we drink summer wine. My sister calls it Poor Man’s Sangria.

4

Satiated, seated by the blue pool now, hot as heaven. Anxieties disperse, join red petals scattered round on stone and grass. Birds dip their beak in the pool’s water. In the sun’s blaze the leaves on their branches shine white. Now I think of the garden I once called home.

Shirtless, I lie on short grass. Its texture tickles my back. My companion, swimming, leaves me to my lonely thinking. (Once we shared summer ruminations. At times our silences run parallel. At others we’re like strangers who don’t meet.)

The cuckoo calls three times, as brazen as a rooster. Perhaps the sun estranges thoughts, reminds me of advancing age, grey hair, dull flesh. Still, in dreams, I fly before I fall.

5

My sister, dressed in green, is dancing the Sevillana as we enter. Two friends are with her; one dances too, the other sounds the beat with flattened palms. They are sisters.

Sunlight dapples my sister’s cheekbones, flickers on her fine drawn features. She dances with her face.

I’d love to paint her like this, in her green flamenco dress, dancing. If I could paint. But she could paint herself. Tres morenas de Jaen, Axa, Fatma, y Maryen ... think of Lorca’s songs.

What does duende really mean?’ Someone asked my sister, at a London supper.

‘Duende means talent,’ she responded. ‘It’s not a word we use much any more.’

Tomorrow is her birthday. Her grandchildren are on holiday on another continent. ‘My sister,’ my companion remarks, ‘looks twenty when she dances.’

6

Later, on the beach. Pavese called the sea a field. Tonight it is, a silver field.

The sky reddens, darkens, scatters stars.

We’re at the mouth of the Guadalquivir, my neighbour says. The Arabs called it something like wad-el-kabir.

‘Andalusian hospitality, too, is Arab,’ someone says.

But this is not the sea. The yellow strand is not a beach. I’ll stick to my terms. Sea or river, the line of water remains a silver field.

7

We eat water-creatures: anchovies and anemones, cockles, langoustines and bream. My neighbour speaks to me of ragged love and separation. My mind and tongue unlock their Spanish. We are, at fifty, childless. My companion, eleven years younger, has a son.

‘You should have a child, the two of you,’ my neighbour says.

‘Ah, I tell her, but we’re not lovers.’

‘We’re best friends,’ my companion adds.

‘Do you still feel Pakistani?’ The Venezuelan to my left asks me.

‘I do, when I feel anything at all.’

The Venezuelan drones on.

‘Muslims in Europe are a demographic problem. In Andalucia, I hear, they want to reclaim ancient sacred places. They should be loyal to their country of adoption. Wouldn’t you say?’

‘I guess I’m a Muslim in Europe too,’ I say. ‘And foreign everywhere I go.’

With one desultory gesture I dismiss an uncongenial conversation.

‘I’m tired of romance,’ I overhear my companion saying.

‘But without love life’s an uphill climb,’ my sister muses.

Now, as I drink manzanilla, I see you in my glass. Perhaps I haven’t thought of you as yet, left you behind with other things in London. Finger dipped in ink of manzanilla, I bring you into being from your place of absence, think of writing you into this narrative. (Like me, I remember, you can’t swim.) Why do we see yesterday as shadow, tell me, call memory a haunting? Echoed crooked smiles, linked fingers, can thrill, become a sudden presence. Should I write: sometimes I think of you and wonder if you really happened, on occasion wish you were here to taste the green figs and the summer wine – or remind you of an evening’s words that spiralled from life’s work into euphoria, an empty bottle’s cork I kept at dawn, some other things you left behind?

8

At midnight we sit on the patio. My sister smokes a cigarillo, I sip brandy poured on ice. A little lizard, startled, runs up the wall. The smell I remember from Sevilla fills the air, from a bush behind my left elbow.

‘Jasmine,’ my sister says.

(I must remember this, to tell you: there’s no frangipani here, that makes it less like Karachi.)

Now it’s nearly 2. My companion has retired to her room, her separate thoughts. (She wanted to visit the Alhambra. Short of time, we couldn’t make it.)

Too often I treat friends like lovers, lovers as friends, give children the attention owed to adults. But friendship’s all that matters. I have no time left for love. (One night – November, and the moon was full – you told me we had nowhere left to go. For a while I’d dreamed that we might travel on. It doesn’t matter any more.)

My sister knows all this. I need to tell her nothing. We sit alone together. The sky hangs dark and low. We continue to talk, of small, of necessary things.

The frangipani tree I planted will be in full flower the next time you’re here ... my sister breaks her sentence. Her eyes are very blue.

9

Eyes shut, I breathe in, lost colours found again: jasmine white, fig green, hibiscus red and something new, unnamed: purple, perhaps.

The fan hums overhead. I recall one mad night’s crossing, and a morning salutation: parted lips brush mine four times, and then – an afterthought? – a fifth. How should I name so accidental an exchange: inconsequence, or parting gift? What would you say?

Next door, my companion turns the tap on. What, I wonder, woke her? By my pillow, in a vase beside a jug of sparkling spring water, a twig of orange bougainvillea leans on jasmine. Like yesterday, it has no shadow and no smell.

The Crane Girl

1

When they first became friends in early autumn, Tsuru disapproved of Murad’s companions, Jime from the Côte D’Ivoire and Vida from Ghana. Tsuru wondered what an Asian could have in common with someone from Africa: was it merely dark skin? She didn’t even pause to think about the differences between a Japanese and a Pakistani.

But after meeting Tsuru, Murad hardly had time for anyone or anything else, even his studies; in late November, before the end of term, Mrs Fogg-Martin had phoned his father to complain he’d missed two of her afternoon poetry classes.

As often as he could, Murad would go back with Tsuru to the flat she shared with an Australian girl called Pam and a Canadian boy named François. Sometimes they’d sit in the communal sitting room and listen to Tsuru’s collection of American, English and Spanish records. But Tsuru thought that her flatmates were scroungers; she couldn’t stand their marijuana joints and the cheap Rioja they loved drinking, and transferred her record player to her bedroom. Murad learned to smoke with Tsuru: or rather, to be able to smoke with her, he taught himself to inhale in his own room, choking, spluttering fumes out of his open window towards the empty patch of land people said was the burial ground of the Tyburn martyrs. Soon he was buying a packet of Players’ every day – the cheapest he could find – and telling his father the price of sandwiches in the canteen had gone up.

The tutorial college they attended was in a shady residential street just off Gloucester Road. Tsuru lived within walking distance, in Airlie Gardens; Murad lived off Marble Arch, and he soon discovered he could save fifteen pence a day by taking the bus, which cost less than the tube from Park Lane to Cromwell Road. In the afternoon he’d get off just past Hyde Park Corner and walk home through the park; that was even cheaper, and it helped him save for the cigarettes he bought to replace those he’d accepted from Tsuru and her friends.

When he’d arrived in London in May with his sister to join their father, the park had been, along with the library and Selfridges, their main field of entertainment. There were regular rock concerts – Mungo Jerry, the Kinks, and once the hallowed Rolling Stones. Mahalia Jackson sang gospel unaccompanied and her voice hung over the park like a rainbow. There was also the spectacle of hippies smoking hash and making love in the grass, and Hare Krishna people who handed out lentils and rice to passers-by. In those days they’d had no friends, and films, which they’d seen all the time when they were younger, were expensive unless you sat in the front row near the screen. They went to see Bombay movies once or twice a month at first, possessed by a nostalgia that was almost entirely imaginary, since they’d always had a preference for Western films at home. Passing through the dingy suburbs that seemed to make up most of London filled them with genuine pangs of homesickness for the leafy lanes and elaborate gardens of the neighbourhood they’d left behind in Karachi, or made them miss the broad, airy avenues of the district they’d lived in for three years in Rome. Then his sister had gone to her fashionable girls’ boarding school in Norfolk and he, to save time, had been sent to Elliott House to rush through the O levels he’d already prepared for in Pakistan.

Most of the boys in Murad’s school were Greeks, Arabs and Iranians, and older than he was: they drank, gabbled away loudly in their own languages, and chased after girls in pubs. Many of his schoolmates didn’t wash enough because they thought it girlish to shower more than twice a week, or their landladies simply wouldn’t allow them to. Each group seemed to identify with a national or regional label, playing roles written for them by some invisible scriptwriter. There were Malaysian Chinese boys and girls who banded together; Hong Kong Chinese who only had time for their books; and East African Asians who patronised Pakistanis because they considered them backward and insufficiently Westernised. So he made friends with the Africans who had fluent English and open minds.

In the evenings he would stop by at the local library on South Audley Street. Then, unless his father was taking him out to dinner with acquaintances who had offspring he was expected to befriend, he’d usually stay at home with a book, or very often watch exotic films with titles like Ashes and Diamonds or Yang Kuifei on late-night television. He was developing an interest in Japan through the films he’d seen and a handful of novels he found in translation at the library – he was particularly taken with one called The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea.

When Tsuru came back to school from holiday he was struck by her elegance, which reminded him of the ivory beauties he’d read about, though she didn’t strike him as beautiful at first because she seemed so fragile. She usually dressed in black and her hair was ear-length. She had a nearly perfect oval face; her skin was like smoked cream, her eyes were long, narrow and fringed with blade-sharp lashes, her full mouth parted to display very white and slightly protruding teeth. She sat down at the desk next to his, but they hardly spoke until one afternoon when, without knowing why he was doing what he did, he followed her out of the school building after the literature class to the row of shops on Marloes Road. She was going to buy cigarettes. He lingered under a low tree till she emerged from the tobacconists’, then fell into step with her for a block before asking her if she’d like a cup of coffee at the nearby Wimpy Bar on High Street Kensington. She smiled, unsurprised, and said yes. They talked a little, mostly about classes. Then Tsuru told him she was nearly eighteen, and had lived alone in London since her father, a JAL employee, had been posted back to Tokyo two years ago. Murad, who’d turned fifteen the spring before, told her how his mother had stayed back in Karachi and planned to join them in London the next year. When they finished exchanging life histories it was nearly 5.30. Murad reached into his pocket for money to settle the bill and found he only had five pence, and it would cost him half of that to get to Hyde Park Corner. He couldn’t even pay for his own coffee, let alone Tsuru’s. But almost as if she hadn’t noticed, Tsuru said, ‘You can buy me one next time,’ and put twelve pence on the plate. That was her way: she’d pay for him quite thoughtless once, and another time let him treat her or even ask for a loan.

Later, she told him his blush had given away his discomfort: his blush was one of the many things about him that made him the butt of her jokes and teasing. ‘Remember,’ she loved reminding him in company, ‘the first time you ever took me out for coffee you wanted to know if I was a virgin, and then you didn’t have money to pay for our coffees? I knew you’d be a bad date right away then.’ Murad couldn’t remember whether this was true, or one of the many funny stories Tsuru liked to tell about him in front of others. He knew he had asked her about her love life, but thought they’d known each other at least a month by then. What he remembered was the way she’d repeated the word ‘virgin’, pronouncing it ‘baaar-jin’, though her English was usually unaccented. And he also remembered her answer: she’d ‘played around’ with a cousin when she was twelve, and then had had two boyfriends, one who was much older, and the one she was still seeing, Rick, who lived with his parents in Sevenoaks where she often spent weekends. He was bemused, too, by the thought that she’d assumed he wanted to ask her out on a date.

Murad himself had come very close to losing his virginity with a childhood friend during a wedding celebration in Karachi, at which about ten teenagers had turned a late-night revel into a slumber party. But he and his putative sweetheart hadn’t really known how to go beyond deep kisses and long embraces; then, as they were fumbling with buttons and bindings, they’d been interrupted by people getting up for drinks of water and visits to the loo. In the morning they still were still technically virgins. By the time he’d been in London a few months, he thought it best to be honest, at least to Tsuru, about his inexperience. Anyway, he’d never met anyone remotely suitable. You had at least to like someone a lot to make love with them – and he, where would he meet that someone who’d like a being as awkward and plain as he felt he was?

Tsuru thought his innocence was quite funny and announced it to Pam and François in his presence as soon as she could. ‘The little darling, shouldn’t be a problem with his looks, he’s a nice looking bloke,’ Pam hooted. Murad felt his ears and cheeks heat up. ‘He’s OK if you like dark types,’ Tsuru mused, as if Murad weren’t there. ‘Me, I like blondes.’ The word came out as ‘bronders’, Murad noticed, wondering why Tsuru’s accent sometimes betrayed her. But he was aware then, for the first time, that it mattered to him what Tsuru thought about him, and that she shouldn’t, as a friend, have made fun of him like that in front of Pam.