28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

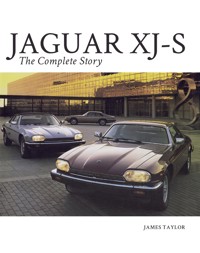

A history of all four generations of compact Jaguar, and their Daimler equivalents, tracing the gradual development of Sir William Lyons' original idea over a period between 1955 and 1969. From the powerful, luxury MK 1 and 2 cars to the 4.2-litre 420, this book covers design, development and styling; special-bodied variants; racing performance; buying and owning a compact Jaguar saloon model and, finally, specifications and production figures.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Jaguar Mks 1 and 2, S-Type and 420

James Taylor

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© James Taylor 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 113 0

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Timeline

CHAPTER 1 JAGUAR BEFORE THE COMPACTS

CHAPTER 2 DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE JAGUAR MK 1

CHAPTER 3 JAGUAR MK 1 (1955–1959)

CHAPTER 4 DEVELOPING THE JAGUAR MK 2

CHAPTER 5 JAGUAR MK 2 (1959–1967)

CHAPTER 6 JAGUAR 240 AND 340 (1967–1969)

CHAPTER 7 DAIMLER V8 (1962–1969)

CHAPTER 8 DEVELOPING THE JAGUAR S-TYPE

CHAPTER 9 JAGUAR S-TYPE (1963–1968)

CHAPTER 10 DEVELOPING THE JAGUAR 420 AND DAIMLER SOVEREIGN

CHAPTER 11 JAGUAR 420 AND DAIMLER SOVEREIGN (1966–1969)

CHAPTER 12 SPECIAL VARIANTS OF THE MK 2, S-TYPE AND 420

CHAPTER 13 THE LEGACY OF THE COMPACT JAGUARS

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book combines the essence of two earlier books I wrote for Crowood – Jaguar M k 1 & 2, The Complete Story and Jaguar S-type and 420, The Complete Story. It made complete sense to me to combine the stories of all four compact Jaguar saloons into a single book because all were developed from a single original design and all remained quite closely related. However, times have changed since I wrote those original books in the mid-1990s and more information has become available about some aspects of the compact Jaguar story. So this book contains some material that is old, and quite a lot that was not in the original volumes.

Some of the research I did all those years ago on the development of the original 2.4-litre Jaguar was originally published in Jaguar World magazine, and I am still grateful for that opportunity. Back in the mid-1990s, I was also privileged to interview Cyril Crouch, who had been Jaguar’s assistant chief and later chief body engineer when the cars were being developed.

That was then, and I am pleased to acknowledge the more recent help of several people in bringing this present volume together. Karam Ram at the Jaguar Heritage Trust helped out with vital photographs from the factory archives, Simon Clay took a number of the photographs of all four generations of compact Jaguar, and Magic Car Pics provided the photographs I could not find elsewhere. The Kent Police Museum provided some fascinating photographs, and I am particularly grateful to Paddy Carpenter of the Police Vehicle Enthusiasts’ Club for giving me access to the club’s collective knowledge and photographic archives.

James Taylor Oxfordshire April 2015

TIMELINE

1955 (October)

2.4-litre model announced

1957 (February)

3.4-litre model announced

1957 (November)

2.4-litre Automatic becomes available

1959 (September)

Mk 2 models available with 2.4-litre, 3.4-litre and 3.8-litre engines

1962 (October)

Daimler 2.5-litre V8 announced, based on Jaguar Mk 2

1963 (October)

S-type announced, with 3.4-litre and 3.8-litre engines

1966 (August)

420 and Daimler Sovereign announced as further developments of S-type range

1967 (September)

240, 340 and Daimler V8-250 announced

1968 (June)

Last 3.8-litre S-type built

1968 (August)

Last 3.4-litre S-type built

1968 (September)

Last 340 and 420 models built

1969 (April)

Last 240 models built

1969 (July)

Last Daimler Sovereign built

1969 (August)

Last compact saloon of all built – a Daimler V8-250

CHAPTER ONE

JAGUAR BEFORE THE COMPACTS

When Jaguar introduced their new compact saloons in 1955, the company was enjoying an unprecedented wave of success. Most important in that success had been the US market, where the marque had been able to exploit the postwar fascination for European cars that would also make the fortunes of MG, Triumph and others.

To a considerable extent, that success helped to shape the basic parameters of the new compact saloons. Despite the radically new (for Jaguar) engineering that went into them, they had to conform to public expectations of the Jaguar marque. And those public expectations were inordinately high in 1955.

Jaguar’s range for the year that preceded the compacts’ introduction consisted of two basic models. One was the Mk VIIM saloon and the other was the XK120 sports car, available in either open or closed forms. The Mk VIIM was a large luxury saloon, offering spacious accommodation with a traditionally British wood and leather interior, while the XK120 was a stylish and charismatic two-seater. In many respects, they were as different as chalk and cheese and yet they had three very important factors in common: pricing, performance and good looks. It was these three characteristics that defined the Jaguar marque for the motoring public of 1955.

Looking positively benign as an older man in the 1950s, William Lyons (who would be knighted in 1956) still had a keen eye for a good shape.

The 1948 XK120 sports model was an oustanding success for Jaguar and was the first production car to have the company’s own XK engine. The curvaceous shape was superb, as this photograph shows, and the wheel spats are a very modern touch.

It had always been Jaguar’s policy to keep prices as low as possible, both in order to undercut competitors and to promote an image of value for money. In this, the Mk VIIM and XK120 were fully representative of the Jaguar tradition. The Mk VIIM was essentially a ‘poor man’s Bentley’, and in 1954 its basic retail price, inclusive of taxes, was £1,616. The cheapest Bentley then available cost around three times as much. As for the XK120, which was similarly priced, its most obvious rivals came from the likes of Ferrari and Aston Martin, and all of them were vastly more expensive than the Jaguar.

High performance was also a Jaguar trademark, and the company had furthered its image in that field with a spectacular series of successes in international motor sport during the early 1950s. First had come the C-type sports racers (strictly known as XK120C models), which had won the Le Mans 24-Hours road race in 1951 and again in 1953. Then in 1954 had come the D-type, which won at Le Mans in the early summer of 1955. But perhaps the most important aspect of these and other sporting victories, as far as Jaguar customers were concerned, was that the sports racers depended on race-tuned derivatives of the same engine that powered both the Mk VIIM saloons and the XK120 sports cars.

That engine – the XK twin overhead camshaft 6-cylinder – had first appeared in 1948 and would not finally go out of production until more than forty years later. In road-going 3.4-litre form, it endowed the big Mk VIIM saloon with a top speed of 103mph (165km/h) while the XK120 laid claim to 120mph (193km/h) or more. For the early 1950s, this kind of performance was the stuff of which dreams were made: the average family saloon of the time struggled to reach 70mph (112km/h).

Both the XK120 and the Mk VIIM (announced as a Mk VII in 1950 and newly updated in 1954) were strikingly styled cars. Bulky though it undoubtedly was, the saloon looked elegant thanks to its graceful curves and sweeping wing-lines. It had a special sort of presence that was lacking in other saloons of its day, and when parked alongside the rather upright Bentleys and Armstrong Siddeleys of the early 1950s, it appeared low and streamlined. By contrast, it looked upright and traditional next to contemporary American machinery, but that very conservatism (a distinctly British characteristic) distinguished it from the crowd and endeared it to discerning Americans.

As for the XK120, its long and low lines – reminiscent of the sleek pre-war BMW sports cars – stood out in any company. Once again, graceful curves and sweeping wing-lines were the distinguishing features, and the Jaguar could hold its head up in the company of any fashionable Italian exotics from the styling houses of Pininfarina, Vignale, Touring or Zagato. Across the Atlantic, the only additional competition for the XK120 came from the Chevrolet Corvette, which at this stage did not have the attractive lines for which the marque would later become known.

JAGUAR’S ORIGINS

Styling more than any other factor was essential to Jaguar’s roots. Back in the early 1920s, William Walmsley had moved his small motorcycle sidecar business from Stockport to Blackpool where he had met and entered into partnership with the younger William Lyons. Walmsley’s sidecars were notable for their elegant design, and the enthusiastic Lyons, who had served an apprenticeship with Crossley Motors in Manchester before joining the sales staff of a Sunbeam dealership in Blackpool, developed his eye for a good line from Walmsley’s example. In 1922 they jointly formed the Swallow Sidecar Company, and their business was so successful that they were able as early as 1927 to branch out into making car bodies.

William Lyons was a keen motorcyclist in his youth. This photograph shows him in the 1920s astride a Harley-Davidson registered in his native town of Blackpool.

These car bodies had styling that was as distinctive and elegant as the sidecars, but Swallow stuck to a policy of offering bodies for relatively cheap cars. So, while many coachbuilders preferred to work on the grand luxury chassis whenever they could, Swallow instead provided special coachwork for possibly the most mundane chassis of them all, the little Austin Seven. This made their cars attractive to the customer who could not afford an expensive luxury car but nevertheless wanted something that stood out from the crowd of everyday models. The origins of the market positioning that Jaguar cars would later adopt probably lay in this early experience.

The Swallow sidecars had a distinctive elegance about them and soon gained a good reputation.

The next stage was a move into car bodywork. This 1929 advertisement is for the Austin Swallow – based on a cheap everyday chassis but adding an element of style not otherwise available.

There were closed bodies by Swallow, too. This is a 1931 example, again on an Austin chassis, and shows the two-tone paintwork and V-screen typical of the breed.SANDRA FAUCONNIER/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

One important factor in Swallow’s success was pricing, and by adopting quite sophisticated production processes the company was able to minimize the cost of making its bodies. So it was that, when the growth of their business forced them to seek larger premises, Walmsley and Lyons looked carefully at how best to use this new opportunity to minimize costs further. One overhead they had been unable to control was the cost of transporting chassis to Blackpool from the Midlands heart of the motor industry; and they had already recognized that it was easier to recruit skilled staff in the Midlands than in Blackpool. The solution was therefore obvious: Swallow would move to the Midlands. And so the company moved to premises at Holbrook Lane, in Coventry’s Foleshill district, in the autumn of 1928.

Expansion continued. Lyons introduced further new production methods and before Christmas 1928 had pushed the rate of production up from twelve car bodies a week to fifty. The sidecar activities meanwhile continued. In 1929, Swallow took a stand at the Olympia Motor Show, and that year they also began to work on a wider range of chassis, including Fiat, Swift and – most notably – Standard. From early 1931 there were Swallow bodies for the Wolseley Hornet with its pioneering ‘small six’ engine, too. In all cases, their combination of attractive lines and striking paintwork completely transformed the perpendicular look of the originals, and created cars that were genuinely different from others available in Britain. Mechanically, however, they were unmodified. The next logical step was for Swallow to start building cars that were mechanically as well as bodily different from anything that could be bought elsewhere, and in 1931 they took that step.

The second-series SS 1 coupé introduced for 1933 had much better-balanced lines than the earlier model of the same name. Those are of course dummy hood irons; rear-seat passengers could not see much out of the car!

FIRST SS MODELS

The new models that Swallow announced in October 1931 are often described as the company’s first complete cars, although to call them that is really overstating the case. Standard, content with the special bodies Swallow had been offering on their chassis since 1929, had agreed to supply Swallow with their 16hp (2-litre) and 20hp (2.5-litre) 6-cylinder engines, fitted at the Standard works into a special chassis designed to meet Swallow’s requirements. The key to this chassis was that it was much lower than those normally fitted to saloons of the period, which enabled Swallow to clothe it with rakish new sporting bodywork.

It was William Lyons, always the front man at Swallow, who had secured Standard’s agreement, and it was he who had persuaded them to allow the new car to be badged as an SS. Those letters probably stood for Standard Swallow, but their real significance was that Swallow now had a marque of their own. The SS1, as the 6-cylinder car was called, went on sale in 1932, and was then accompanied by a much smaller new model based on the Standard Little Nine chassis with its 4-cylinder 1-litre engine. Even though this was more in the vein of Swallow’s earlier rebodying efforts, it was also badged as an SS – in fact as an SS2 – and this development made fairly clear what Swallow’s next move was likely to be.

The company name had already changed twice, the original Swallow Sidecar Company becoming the Swallow Sidecar and Coachbuilding Company in 1926 and then the Swallow Coachbuilding Company a year later. From October 1930 it had become a limited company and now it was only a matter of time before the name changed yet again to reflect the nature of the new business. In 1933 Lyons and Walmsley set up a new company with the name of SS Cars Ltd and at the end of July 1934 they purchased Swallow.

The SS Jaguars were based on Standard running-gear, but had low-slung and stylish bodywork. This 1935 example was photographed at the Salon Privé event at Syon Park in 2014.

From then on, Lyons’ primary objective was to establish the company as a credible builder of complete cars. Styling remained important and the later SS models were offered with a variety of attractive bodies. Road performance to match that styling was also important. SS improved the lukewarm performance of the early SS2 models as soon as they were able by fitting larger and more powerful new engines provided by Standard. A gradual process of redesign made the SS1 and SS2 much better cars all round and by 1935 SS had become established as a small-volume maker of stylish sporting cars costing rather less than their exotic looks suggested.

WATERSHED – THE SS JAGUARS

By this stage, high performance had become a very important ingredient in Lyons’ vision of SS Cars. As Standard had nothing in the offing that was likely to fit his future requirements, he turned to tuning expert Harry Weslake and asked him to develop the big Standard engine for more power. Weslake’s solution was to redesign the top end of the engine with a new cylinder head and overhead valves in place of side valves. Lyons somehow managed to persuade Standard to manufacture this revised engine exclusively for SS Cars.

However, Lyons wanted more. The new engine needed to go with a new body, and for the new body it would be necessary to design a new chassis. The bodywork was something he was more than capable of tackling himself, but there was no one at the Foleshill works who had any experience of designing chassis. This was why SS Cars took on their first proper engineer in April 1935. William Heynes, who joined the company from Humber, was later to become a central figure in the Jaguar story.

Stunningly attractive, this was the first of the SS Jaguar saloons. This example dates from 1937.

The new car was ready in October 1935. Seeking to give it a new name, Lyons had settled for Jaguar, after the First World War Armstrong Siddeley aero engine that had interested him many years earlier. And so the new SS Jaguars went on sale for 1936, a range of sleek sports saloons and open four-seat tourers. In addition, there was a new short-wheelbase two-seat sports model called the SS90 – an important model historically because it was the first proper sports car from the company. The saloons could be obtained with either 1.5-litre or 2.5-litre engines, the smaller one actually having a capacity of 1608cc and being a production Standard side-valve 4-cylinder, while the larger engine had 2664cc and the Weslake overhead valve arrangement. The open cars, meanwhile, came only with the larger engine. Although both SS1 and SS2 models remained available alongside the newcomers, their production would soon end.

The optional leaping Jaguar mascot is in evidence on this 1938 SS Jaguar saloon, photographed by the auction house Historics at one of their sales. The discreet indicator light visible in the wheel arch was not an original feature.

Towards the end of 1935, William Walmsley left SS Cars and joined a caravan manufacturer in Coventry. The split appears to have been amicable and probably resulted from Walmsley’s desire to avoid the complications and stresses of running a large company such as SS Cars seemed set to become. With his departure, SS cars was floated as a public company and thereafter was obliged to have its own board of directors who met at regular intervals. However, the board meetings of SS Cars Ltd were more of a legal formality than anything else: in reality, Lyons now took over the running of the company.

Introduced in 1938, the SS 100 had the 3½-litre engine in a lightweight structure and could reach 104mph (167km/h).

The SS Jaguars were further improved for the 1937 model season but the major changes came that autumn when the 1938 models were announced. For a start, the traditional coachbuilt bodies with their wooden frames had been replaced by all-steel bodyshells of similar appearance, which were both lighter and cheaper to manufacture. These had been joined by a new wooden-framed drophead coupé body which added to the SS marque’s upper-crust pretensions. The 1.5-litre engine, too, had been reworked and now sported overhead valves, giving the engine much more performance than the old side-valve engine.

In addition, there was a sleek new sports tourer called the SS100, available with either the 2.5-litre engine or a new 3.5-litre type, which could also be had in the saloons and drophead coupés. Although this was in fact yet another development of the Standard 6-cylinder, and was once again made exclusively for SS Cars by Standard, it was still the closest the Foleshill company had yet come to an engine they might call their own.

WARTIME

By the time war broke out in 1939, the SS Jaguars had already established a formidable reputation. At home, they had been eagerly adopted by the sporting fraternity and there was even an SS Car Club for enthusiastic owners. Looking back rather wistfully in 1944, Montague Tombs of The Autocar magazine described the SS cars of the late 1930s as ‘capable of providing an outstanding performance on the road, and offering exceptional value’. Yet the SS Jaguars were by no means common: by the time the Foleshill factory ceased car manufacture and focused on the production of military materiel in 1940, just 14,383 had been built in five seasons. Of the earlier SS1 and SS2 models, there had been no more than 6,029 examples.

When the war came, SS Cars Ltd was poised on the brink of further expansion. Production had increased enormously to meet the rising demand during 1938–39, and 1939 had seen a record output of 5,320 cars. Most popular of all was the steel-bodied 1.5-litre saloon, which accounted for over 60 per cent of that total. During 1939, William Lyons had bought Motor Panels, one of SS Cars’ suppliers of body parts. His intention had been that SS Cars should be able to manufacture their own bodies entirely in-house, which would have minimized costs and given the company greater flexibility in the manufacture of their bodies.

However, the expansion never took place. Like every other motor manufacturer, SS Cars was obliged to respond to the needs of the armed services. The Foleshill plant started to turn out aircraft parts, took on aircraft repair work, and in 1944 designed and built some experimental lightweight miniature jeeps intended to be carried in transport aircraft and parachuted into action. Meanwhile, the Swallow Sidecar Company – which still existed as an SS subsidiary – took care of the entire requirements of the Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force for motorcycle sidecars.

There was, therefore, little time to spare for thinking about new car designs or improving the standing of the company – although Lyons and those close to him were far from inactive on the matter of future designs. In fact, the war proved a major setback for SS Cars, and Lyons was obliged to sell Motor Panels shortly after hostilities ended for the simple reason that SS could not afford to keep it on and expand as they had planned six years earlier. The Swallow Sidecar subsidiary was also sold off in 1945 in order to raise capital.

In the meantime, Standard had announced that they did not wish to resume production of special engines on behalf of SS Cars when the war was over. Fortunately for the smaller company, they were quite prepared to sell the tooling for the 2.5-litre and 3.5-litre 6-cylinder engines, and at an advantageous price. Lyons seized this opportunity with both hands and by the middle of 1945 the redundant Standard tooling had been installed at SS Cars’ Foleshill plant to give the company its very own engine at last. Tooling for the 1.5-litre engines remained with Standard, and that engine soon reappeared in cars from the Triumph marque that Standard had bought as the war drew to a close.

There was one final change at Foleshill before car production resumed over the summer of 1945. The initials SS had taken on negative associations during the war years, as they had been used by Nazi Germany’s notorious frontline combat troops. Clearly, with sour memories of SS brutality lingering in the minds of British citizens, any company bearing those initials was likely to be shunned. So at an extraordinary general meeting in March 1945, William Lyons had his company’s name changed to Jaguar Cars. It was the logical choice and a happy one.

JAGUAR IN THE LATE 1940S

The British economy had been shattered by the immense cost of the war and the government of the day saw as its clear priority putting that economy back on a sound footing. This could only be achieved by a combination of austerity measures to limit consumption at home and an emphasis on foreign trade to earn revenue abroad.

The car makers, in consequence, were encouraged to build cars primarily for export, and the government ensured that they would comply by rationing sheet steel and allocating it in quantity only to those companies that could show a good export performance. For Jaguar, the need to export was an entirely new concept; although a few cars had been exported in the late 1930s, the company had been able to sell all it could produce on the home market and had therefore never gone to the trouble and expense of setting up overseas distribution networks. But now, it had to.

The first post-war Jaguars were visually very similar to their pre-war counterparts. This elegant left-hand-drive Mk IV tourer was photographed for auctioneers H & H when it passed through their hands. Again, discreet indicators have been added for safety – in this case, just inboard of the bumper ends.

Like the majority of other British car manufacturers, Jaguar started production after the war with cars that were essentially little changed from those they had been making when production had been halted in 1940. Standard had agreed to resume supplies of the 1.5-litre engine for the time being (although post-war versions differed from prewar types), and so a full range of three engines was available. The first bodies were all saloons, however; drophead coupé bodies did not become available again until December 1947, and then only with the 6-cylinder engines – and the SS100 open tourer was never revived.

It was typical of Britain’s insularity, even in the second half of the 1940s, that Jaguar should have thought only in terms of right-hand-drive cars for export. The company had never built left-hand-drive cars before the war and it seems to have resisted the idea as long as possible. However, new and promising markets like the USA were only prepared to put up with right-hand-drive cars as a novelty for a limited period. Jaguar exports to the USA started in January 1947 and by August that year the company had been forced to capitulate and start making left-hand-drive models.

Developing the XK Engine

Jaguar had no intention of continuing with its pre-war 1.5-litre, 2.5-litre and 3.5-litre models for much longer. With his original plans for Jaguar’s expansion in the early 1940s in ruins, Lyons had nonetheless begun during the war years to think of the new car that would eventually take over from the SS Jaguar range. Most importantly, he wanted his new saloon to be a genuine 100mph (160km/h) car – a 1939 3.5-litre saloon was capable of about 92mph (148km/h) – and that meant he would need a new engine. For maximum power, he thought it should have the twin overhead camshaft configuration that at the time was the preserve of racing machines and some exotic road cars. However, it was widely believed to be too complicated to produce economically and too difficult for the average garage mechanic to service and maintain.

A batch of Mk V saloons destined for foreign markets. Exports became vital to Jaguar in the late 1940s.

So it was that Lyons began to discuss with his engineers ways of achieving what he wanted. The design target was 160bhp, which had been achieved for brief periods with a highly tuned 3.5-litre engine in an SS100 in 1939, and the discussions mostly took place while Lyons and others were on fire-watching duties at night in the Foleshill factory. Chief among those involved were Bill Heynes, SS Cars’ first engineer; Wally Hassan, head of research and development and formerly with Bentley and ERA; and newcomer Claude Baily, who had joined SS Cars from Morris on the outbreak of war. Independent specialist Harry Weslake would later be consulted about the design of the cylinder head and combustion chambers.

The work started in earnest during 1943 and the first experimental engines were 4-cylinder types. In due course a satisfactory design was developed and Jaguar built a 6-cylinder prototype. In the form eventually adopted for production, this displaced 3442cc and put out exactly the 160bhp that had been Lyons’ design target. It took on the name of the XK type.

Lyons decided not to put the new engine into his existing models but rather to make it the centrepiece of an all-new saloon with new chassis, suspension and body as well as the new engine. Work on the new body design quickly demonstrated that it would need large pressings that Jaguar could not make itself now that Motor Panels had been sold. So Lyons turned to Pressed Steel, who were happy to accept the contract but needed a year to tool up for the new saloon body.

Meanwhile, Jaguar needed to do something about the current range of cars, because even the seller’s market of the late 1940s could not be expected to tolerate pre-war designs indefinitely. By 1947 many other manufacturers had come up with new designs and these were making the Jaguars look increasingly old-fashioned. To bridge the gap and keep interest in the marque alive until the new saloon could enter production, Lyons therefore decided to develop the existing saloons further – and to show off his new XK engine in a striking-looking sports car that would attract sales in the newly opening US market.

The XK120 was initially given a woodenframed body with aluminium alloy panels, but high demand forced Jaguar to switch to a steel body that could be volume-produced.

With a keen eye for the publicity to be gained from record runs, Jaguar took the XK120 to the new Belgian motor-road at Jabbeke, where a long straight section provided the ideal venue for speed runs. Pictured in 1949, the white car was only mildly modified. In 1953, Jaguar’s chief test engineer Norman Dewis sat under a streamlined ‘bubble’, the headlamps had been streamlined and the bumpers had been removed – he broke the production car record with an astonishing 172.4mph (277km/h).

Mk V Saloon and XK120 Sports Car

For the new saloon, Lyons had the chassis stiffened and equipped with a torsion-bar independent front suspension in place of the old leaf-spring type. He drew up a new body, broadly similar to that on the existing cars but markedly more modern in appearance, and he made sure that this body could be built in the traditional way at Foleshill. The result was a much heavier car than those it replaced, and that was one reason why the new Mk V Jaguar (as it was called) came only with the 6-cylinder 2.5-litre and 3.5-litre engines. One other reason for the absence of a 1.5-litre version must also have been that Lyons no longer wished to depend on Standard for one of his engines.

The XK120 made a name for itself in rallies as well. Most successful of all was NUB 120, with a string of victories in the early 1950s for Ian Appleyard, which is today preserved by the Jaguar Heritage Trust.

The Mk V Jaguar was announced in October 1948 at Britain’s first post-war London Motor Show. Available in both saloon and drophead coupé forms, it was an elegant if unspectacular car, of which most examples went abroad to help Britain’s export drive. Lyons knew he had bought time until his new 100mph (160km/h) saloon could enter production, but he probably had little idea just how important Jaguar’s second new model at the 1948 Motor Show was going to be. That car was called the XK120.

In the Jaguar scheme of things, the XK120 was a belated replacement for the pre-war SS100. It was not really intended for long-term production, and had a wooden-framed body with aluminium panels that could only be made by hand in the traditional way. When it became a huge sales success, the body had to be redesigned as an all-steel structure for volume manufacture in early 1950.

The XK120 had a shortened version of the new Mk V saloon chassis, clothed with sleek and streamlined two-seat bodywork styled as usual by Lyons and clearly drawing some inspiration from the pre-war BMW 328 Mille Miglia roadsters. That alone was attractive enough to have guaranteed its sales success, but in addition the car became the showcase for the new 3.4-litre 6-cylinder XK engine. In the light sports-car body, this gave extraordinary performance for the time, and the XK120 went on to become a major export success. By the time it was succeeded by the rather better developed but generally similar XK140 in 1954, more than 12,000 examples had been built.

MK VII – THE 100MPH SALOON

The Mk V soldiered on for two more years before Jaguar’s new saloon was ready to be launched, but all those who saw the new car at the 1950 London Motor Show agreed that it was worth the wait. The car’s flowing lines echoed those of the XK120; the 3.4-litre XK engine offered a top speed of more than 100mph (160km/h); and somehow, Jaguar had managed to keep the basic price below £1,000 – the figure above which cars attracted a higher rate of purchase tax. Jaguar had called it the Mk VII, deliberately skipping a number after the Mk V because the contemporary Bentley saloon was known as the Mk VI.

The car’s pricing was hugely attractive, but it was of largely academic interest to British car buyers because the Mk VII was intended initially for export only. In pursuit of that aim, Jaguar whisked the London Motor Show car across to New York as soon as the show ended. There, the car was accorded a reception perhaps even more rapturous than the one it had received in London. Within three days, Jaguar had taken orders for no fewer than 500 cars in the USA. Following the success of the XK120 sports car, Jaguar had now definitively broken into the transatlantic market, which would soon become their largest single source of income.

Demand for the Mk VII and the XK120 built up so quickly that Jaguar’s Foleshill premises were bursting at the seams by 1951. They were very fortunate that year to be able to purchase a redundant Daimler plant at Browns Lane, near Coventry, and to move their entire manufacturing operation there. It was a good thing they did, for demand would continue to expand, driven by the US market.

It was US demand that led to the introduction in 1953 of an optional automatic gearbox for the Mk VII Jaguar. Next came an overdrive, more popular in Europe where Autobahn, Autostrada and the new Belgian motor-roads offered opportunities for long-distance, high-speed cruising. Then in the autumn of 1954, at the same time as the XK140 replaced the XK120, came the substantially revised Mk VIIM with a more powerful engine, new bumpers and a host of minor but valuable improvements. And all the time, Jaguar’s reputation was growing as fast as its production volumes. Before the introduction of the XK120 and Mk VII, Jaguar’s annual production figures had hovered at a little over 4,000; by 1954, with both models selling strongly in the USA and sales on the increase in the home market now that restrictions had eased, the annual totals were regularly hovering around the 10,000 mark.

This improvement in Jaguar’s fortunes had far-reaching effects, for without it the company would not have been able to finance the design, development and introduction of a new range of saloon cars, which increased the number of its basic product ranges to three. Those cars were the compact Jaguars, which entered production in 1955.

The XK engine had been designed primarily to power Jaguar’s new large saloon car, and this was it – the Mk VII of 1950. Though the car was large and heavy, its lines were graceful and the 3.4-litre engine made it capable of over 100mph (160km/h).

CHAPTER TWO

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE JAGUAR MK 1

Many of Jaguar’s engineering records from the 1950s still survive, but sadly there is very little relating to the design and development of the compact saloons. After all this time, the most likely explanation is that the crucial documents were tossed into a skip during the iconoclastic days of Jaguar’s ownership by British Leyland. So the story of how Jaguar’s engineers created these iconic saloons has to be pieced together from the few pieces of the jigsaw that remain available.

THE NEED FOR A NEW JAGUAR

It is often assumed that Jaguar missed their smaller-engined saloons after the demise of the 1.5-litre and 2.5-litre models in 1949. The big Mk VII cars with their 3.4-litre engines were selling into the very top end of the traditional Jaguar saloon market, and the would-be Jaguar owner who could not afford a car of that calibre was therefore obliged to buy from another manufacturer. However, a weakness of this argument is that it suggests Jaguar sales were suffering in the absence of these smaller-engined saloons. In fact, the very reverse was true.

Jaguar sales had done nothing but increase since the last of the smaller-engined cars had been built. The final examples of the 1.5-litre had been built in 1949, when Jaguar had made 4,190 cars. During the 1950 model year that followed, when only the 2.5-litre and 3.5-litre engines were available in the Mk V saloons, production shot up to 7,206 cars. Even more revealing is that the best-selling Jaguar of all in 1949 and 1950 was the 3.5-litre Mk V saloon; it sold more than three times as many as the XK120 sports models and around four times as many as its 2.5-litre sibling. All this makes abundantly clear that it was the big-engined saloons that Jaguar buyers wanted and that the smaller-engined cars were not being missed. It was, above all, the performance available from the big-engined cars that made them so popular.

So why did William Lyons decide that Jaguar should develop a third range of cars? There seem to have been two reasons. First, Lyons wanted to give Jaguar a more solid market base than was possible with his company’s existing two-model strategy. Second, the company was expanding rapidly in the 1950s and it was important to build on that expansion in the most appropriate way for Jaguar’s future.

Jaguar was certainly doing well as the 1950s opened. Sales were up to such an extent that the company was forced to move to larger premises in Browns Lane simply so that it had enough space to match production to demand. However, it must have been very clear to Lyons that Jaguar’s success was potentially fragile. After 1950, it was totally reliant on two models – the Mk VII luxury saloon and the XK120 sports car. Both of these sold in specialist areas of the car market, and both of those market sectors were likely to be volatile.

Recent experience had shown that when the economy was in the doldrums, the first sectors of the car market to suffer were precisely those in which Jaguar was operating. There was also the problem that the company was depending more and more on export markets, and events in the early 1950s showed that overseas markets could be closed almost overnight if governments decided to protect their economies by imposing trade bans or high taxation on imports. Jaguar could not risk remaining in this position for long: the company needed a model that would sell in the less volatile middle sector of the market, and one which would sell strongly at home so that it was less dependent on exports.

Such a car would help protect Jaguar’s interests against the uncertainties of the world economy, and it would also help the company to continue its expansion if the economic situation remained stable. The new Browns Lane premises were large, and it must have been obvious that Jaguar would never fill them completely with assembly lines for the Mk VII saloons and XK120 sports cars. To get the most out of their new investment, therefore, they needed a car that could be made in larger volumes than either of these. If it was successful, it would move Jaguar from the ranks of the specialist manufacturers into the ranks of the volume car makers, which would guarantee the company a more stable future. However, it would be important that a new volumeproduction Jaguar should not debase any of the qualities on which the marque had built its reputation. This consideration had a profound effect on the eventual design of Jaguar’s third range of cars.

It is difficult to sort out the sequence of surviving Jaguar 2.4 mock-up photographs, but this one was certainly early. The flip-front plan is in evidence here (note the curved shut-line just behind the wheel arch), along with slim bumpers painted in the body colour. The major details are already in place, though.

This photograph shows the other side of the same mock-up, this time with some wheels in place to give a fuller effect. The wheel trim is a production Jaguar type, but with a section apparently painted in the body colour, as on the Mk V models. Perhaps that was what came to hand most easily when a hubcap was needed!

This is the same mock-up again (note the odd headlamps), but this time with different A-pillar shapes being tried and also, it appears, with a more conventional bonnet. Shut-lines are in evidence on both sides, although one side differs from the other. There is also a raised centre section.