9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

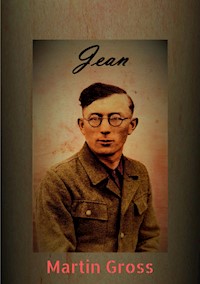

In this book, Jean Gros tells his life story from his youth to his release from captivity as a prisoner of war. He was born in 1922 as the child of German-Romanian settlers, under the name Ioan Grosz, in the Romanian Banat. The family lives in the small village of Ivanda near the city of Timisoara, where they run a small farm. In this environment, characterised by simple living conditions, Ioan experiences a carefree and mostly happy childhood. This ends, however, when he begins a butcher's apprenticeship in a neighbouring village. From now on, he has to face the first hardships of life. However, this period of his life is still proceeding along the usual lines for the time and the region. This all changes abruptly when the Third Reich sets out to recruit new soldiers from the ranks of the Romanian Germans. Ioan also gets caught up in the mills of the Nazi war machine, and like most of his compatriots, ends up in the Waffen SS. As the book progresses, it describes his traumatic war experiences and the depriving circumstances under which the missions are carried out. During his sorties he is also wounded several times. Despite all adversity, he tries to maintain contact with his family and childhood sweetheart, but this is not always successful, and the uncertainty about his family's circumstances becomes his constant companion. The war ends for him with another wound and years of imprisonment. The vivid description of the events takes the reader on a journey through Jean's life, which is exemplary for that of many young Romanian-Germans of that era. The reader also gets an impression of the way of life and the further fate of this ethnic community.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 497

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Jean

Memories of a Stolen Youth

A biographical novel

Martin Gross

ISBN 978-3-347-77087-4 (paperback)

ISBN 978-3-347-77088-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-3-347-77089-8 (e-Pub)

Publication and distribution are carried out on behalf of the author by Tredition GmbH, Imprint Service Department, Halenreie 40–44, 22359 Hamburg, Germany.

Translation from German: Martin Gross

Text and design: Martin Gross, Carcassonne

Cover design: Martin Gross, Carcassonne

Printed and bound by Tredition GmbH, Imprint Service Department, Halenreie 40–44, 22359 Hamburg, Germany.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the copyright holder.

© 2022 by Gross Publishing

All rights reserved by Gross Publishing

Against the oblivion

Foreword

Jean Gross, our father, was born in 1922 in the Romanian part of the Banat, a cross-border region in eastern Europe between Hungary, Serbia, and Romania. This enclave of Habsburg Austria, created by mainly German settlers in the 18th century, was divided up after the First World War, and a large part was assigned to Romania. Jean – or Ioan as he was called then – grew up in a large family, typical of the Banat people. During his childhood and youth in a small village named Ivanda, nothing could have seemed further away than the German Nazi Reich. Nevertheless, he, together with about 80,000 other young Romanian men of German origin, ended up being recruited into the Waffen-SS. Exactly how this happened is not clear because he was reluctant to discuss his early life, and talking about the war itself was taboo. This rule was broken only on very rare occasions when he met up with one or other veterans from the war, and they would sit talking for hours over too many bottles of beer. This always occurred in the evening, however, when the children, and me being the youngest, had to be to bed. Nonetheless, I still have fragmentary memories of these rare and strange evenings when there was talk of war experiences – how the Russians had used so-called ‘compressed air’ grenades and how soldiers were found dead without any apparent wounds. They also spoke of beautiful Russian women, the partisans who appeared out of nowhere, dead comrades, the merciless winter cold and days with nothing to eat, but I cannot recall them ever discussing executions or using the term ‘concentration camp’.

However, after his death my mother told me about a short period during which he was on duty at the arrival ramp of one of those concentration camps. Apparently, he was admonished by a superior for wanting to give some bread to one of the arriving prisoners. She also said that he had had a cap embellished with the skull and crossbones, which he removed during his imprisonment. There is a photograph of that cap and a uniform jacket on which the epaulette with the SS skull and crossbones had been scratched away.

This made me want to research the use of Romanians of German origin in the SS, and their training and frequent deployment as concentration camp guards. In this context, I also listened to the transcripts of the Auschwitz and Majdanek trials, which were very helpful to understand the routines of the guards, but also extremely depressing. In summary, it can be said that the majority of Romanians of German origin served in the III SS Panzer Corps, in the SS Division Prinz Eugen or as SS concentration camp guards. The latter were trained mostly in the town Oranienburg. Only a hand-picked few joined the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, his personal bodyguard unit. There were also shifts between divisions, especially among the guard crews and the fighting units. In any case, these Romanian Germans ended up mostly in the SS and not in the regular German forces.

I remember hearing my father scream at night when his memories of the war plagued him. This usually lasted for just a few seconds before my mother's soothing voice would wake him up.

After his death, I kept asking myself what he could possibly have gone through and done during this turbulent early period of life over which he had had little control. What was it, that he had carried in his personal ‘rucksack’ after the war and his imprisonment? I left it at that for a long time before I began to devote myself to doing some genealogical research. In the course of this, I also investigated the living conditions in the Banat in the pre-war period and the changes that took place as a result of the influence of the National Socialists. I became aware that my father had been a witness to the beginning of the downfall of a centuries-old ethnic community. Between his call-up for military service and his one and only return visit to Romania at the end of the 1960s, almost everything that generations of so-called Danube Swabians had built up was lost. At the end of the Second World War, the Russian occupiers, supported by the new communist regime, deported tens of thousands of people to labour camps in the Soviet Union. Almost a quarter of these did not survive the hard labour and miserable conditions in these camps. Most of those who were released never returned to Romania, but went to one of the West German occupation zones.

After the war, my father and his sister, Leni, lived in Germany. His other siblings who were in Romania were not allowed to leave. Nicolae Ceausescu's regime regarded them as a commodity that could be sold to the Federal Republic of Germany in later years. For many years they did not dare to apply for emigration permits for fear of losing all of their remaining possessions, with no compensation. It was only when the economic situation became completely unbearable in the 1980s that the brothers and their families left the country. Only Elisabeth – called Lissi – my father's older sister stayed behind. She is the only one who was buried in Romania. My father never saw his parents again.

My motivation for writing this book was the desire to give Jean – who like so many of this generation drifted like a leaf in the winds of war – his own personal story. I did not want the memory of his life – like those of most of my ancestors – to end up being reduced to a series of birth, marriage, and death certificates. Consequently, I have attempted to draw a picture of his life based on fragments of memories, the few available documents and the anecdotes told within the family. Some parts of this biographical narrative are verifiable, while others are based on contemporary documents and some are freely invented.

At some point, of course, I had to ask myself some questions: What could I assume? How far should or was I allowed to go in my assumptions? For example, was Jean enthusiastic about being recruited into the SS or was he forced to go? Was he involved in executions? If so, how did he behave and what effect did this have on him?

Academic studies have shown that many of the young Banat recruits were quite enthusiastic about the idea of going to war as a member of the German Wehrmacht; some, knowing no better, considered the Waffen-SS to be part of it. Most were pleased that they could thus avoid military service in the poorly equipped Romanian Armata, which was fighting alongside the Wehrmacht in the East. Before the defeat at Stalingrad, the German Wehrmacht had the aura of being invincible – many months passed after this disastrous defeat before the truth about the situation on the Eastern Front became apparent. Meanwhile the promotional films shown by the recruiters in the small villages of the Banat continued to depict a highly mobile, rapidly advancing, victorious army. If you had to go to war, this would be the army of choice. The departures on the transport trains to the training camps in the Reich often resembled public festivities rather than painful farewell scenes. Sometimes everyone from the village would gather in front of the decorated carriages and sing to the music of the village band.

However, there are also many reports of those who objected and refused to go, and those who tried to delay their departure by any means possible. Yet, the pressure from the leaders of the Banat community was enormous because many were Nazis and careerists. They wanted to make their contribution to what seemed like a patriotic war, no matter what. This seems rather bizarre since the Banat people had been living in Romania since the 18th century and had maintained only very loose ties with the German Reich or its predecessors.

As it turned out, the mortality rate of the ethnic Germans in the Waffen-SS was significantly higher than that in the Armata. This was largely due to the generally poor and inadequate training received by the recruits, who were often used as replacement troops for already decimated regiments. In addition, the armaments were inadequate, having originated from the stockpiles of the 1920s. It is also significant that the SS Division Prinz Eugen was a purely ethnic German combat unit that was deployed in the areas in the vicinity of the recruits’ homeland. There was often a lack of ammunition and food supplies during the battles against the partisans in the Balkans, which caused great frustration among the young recruits, who were already disillusioned by the realities they had encountered during their training. This had two effects. First, quite a few soldiers deserted and went back across the border into Romania, where they were not always welcomed. Second, their disillusionment led to them venting their anger in great brutality against the civilian population and the captured partisans. The rules of the Geneva Convention on the treatment of prisoners of war and the sparing of the civilian population were not applied at all, and this led to numerous serious war crimes on both sides.

The extent to which Jean was directly involved in these atrocities is unclear. Yet, one may confidently assume that he witnessed one or the other of these incidents, as it was unavoidable as a member of these combat units. The effect of all this on a young person is difficult to imagine. The atrocities he witnessed and those in which he may have been directly involved, the painful experience of being wounded multiple times, the constant fear of being killed, the unspeakable hardships in the icy trenches, and the sense of loss when the war ended must have weighed heavily on the shoulders of a young person – all the more without any psychological care. Living through all of this and then being alone during a long and at times painful imprisonment in a foreign country must have left its marks. Then he, like hundreds of thousands of other young men who lost their youth in this insane and completely senseless war were expected to return to a ‘normal’ life. The damaging effects of this trauma deserved some recognition, but unfortunately this never happened because there was a post-war culture of wanting to forget, of keeping quiet and of shame. This prevented any recognition of the trauma and psychological damage to these individuals and inflicted additional wounds on these people – wounds that no one wanted to know about or discuss. It therefore became important for me to describe situations in which these pent-up emotions were released.

Jean was taken prisoner of war and, he certainly hoped to be released soon after the end of the war and be able to return home. However, this did not happen. Even though he was not interned in a gulag in Siberia but in the hands of a democratic country, he was not released until more than three years after the war. To make matters worse, Romania declared all German–Romanian members of the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS deserters, which made it impossible for them to return home.

This book deals only with that part of Jean’s life that, for all who knew him, seemed to exist behind frosted glass. For this reason, it can’t be said with certainty that he actually met all of the characters portrayed in this book or that he interacted with them in the ways described here. Others, however, he did meet and there is photographic and written evidence of this. People mentioned who are not part of his family are mostly fictitious, so any resemblance to people deceased or living is purely coincidental.

Martin Gross Carcassonne, 2022

Acknowledgements

My special thanks go to my wife Birgit, who endured my absence, at least mentally, with great patience during the work on this book. She also read the first drafts, which was not always easy reading. It is also thanks to her constant encouragement that I kept going with this project.

A big thank you goes to Glenda Younge for her support on this translation. Without her valuable input and corrections, I would not have arrived at a readable English version.

Another big thank you to all who took the trouble to read this book in its German version at various stages, and gave valuable input on its readability. Those were Maria Schmidt, Hanni Pfaff, Gabriele Pfaff and Ute Reis.

Prologue

Unfortunately, in life one cannot go back in time, not even for a few moments. I really wish I could – and preferably for several years – so that I could do many things differently. But of course, like anyone else I can’t. Only in my thoughts I can travel back to the old days and then those memories of the past are there again, when I was a boy and later a young man. Not that these memories are always pleasant – not by a long shot. That bloody war threw my life off the rails; I really could have done without it. I often wonder what my life would have been like had I not been sucked into the mills of that madness. If only I had been able to stay in Ivanda and continue my life there, perhaps everything would have been fine. Of course, it is idle to think about this seriously, as if one could change the world by dreaming up beautiful things.

My life would certainly not have been easy, but at least it would have been my life, not one determined by some idiots who set the world on fire; by officers who ordered us to do things that no human being should have done. I would not have been forced to live in a foreign country with which I had no affinity other than the history of my ancestors. I would have been with my own family and my people.

But it’s too late for regret, now that I'm lying here dying. I've just had my bottom scratched out – I can't even go to the loo any more. My family is there, or at least some of them. I can't really see them very well, especially without my glasses; everything seems shrouded in a veil. My eyes have always been bad and yet I still ended up in the military. Back then I guess they would have taken anyone who was able to walk towards the enemy. But even walking has been impossible for me since I had that stroke. Like a war invalid I had limped for almost 30 years, but over the last few years even that was no longer possible. Now I am lying here in the nursing home and I know that it will soon be over for me. I am all too familiar with the atmosphere of a military hospital where people lay dying. I survived the war and many other things, and I have lived to be almost 82, but I probably won't make the next three months to my birthday. What a miserable end, tied to this deathbed! However, in my memories I am free and I can return once again to those days when everything still seemed possible.

IN THE BANAT

I was born in a small village called Ivanda in Romania in 1922, a descendant of former German immigrants. To be more precise, I was born in August and upon my arrival the light was very bright. Luckily it was as warm outside as it was in my mother's womb. At least the latter made things easier.

The village of Ivanda is in the Banat, a region on the border between Romania, Serbia, and Hungary. Most of the inhabitants were so-called Banater Swabians, migrants of predominantly German origin. They had immigrated in the 18th century when the monarchy of Austria wanted to repopulate the empty lands devastated after the Turkish wars. Although most of our ancestors did not come from the German region Swabia, this became our ethnic group designation, probably because most of these migrants had travelled down the river Danube from Swabian Ulm. Thus, we cultivated our Swabian culture, or at least what we considered to be Swabian culture. We tried to stay clear of the internal affairs of the Romanian regime in power at the time and above all, we kept mostly to ourselves. We didn’t assimilate Romanian culture and there was never a question of integration. This did not seem to cause the rulers any headaches either, as they held our efficiency and productivity in high esteem. After all, this was the original reason why the Habsburgs had brought us here. They wanted us to take the land and make something of it, and that’s what we, or rather our ancestors, did. None of us became wealthy, except for a few families who moved into the bigger cities and set up businesses. These urbanites also started to get more involved in the political affairs of the country, but not always successfully, while we in the countryside minded our own business. Unfortunately, this was soon to change.

Actually, we just wanted to live peacefully. It was hard enough trying to wring out a living in the humid lowlands. Like most of the community, my parents were simple, hard-working people. My mother Roza took care of the household of six children, four boys and two girls, as well as the vegetable garden. Our father, like so many others, was a farmer, working a few acres of land with his hands and a single ox. My grandmother Marga also lived with us in a small room in the house. I believe my father's family came from Schag, a small town on the road to Timisoara, because we went there one day in a horse-driven cart to fetch her. I have no memory of my grandfather Rudolph, who died a few years after returning from the First World War. My grandmother said that his lungs had given in as a result of exposure to gas in the trenches.

We didn’t have much land so life was a constant struggle, but that's how it was for a lot of people here in the village. Even though everyone had to look after themselves, there was also a lot of solidarity if anybody was in real need of help. We also had our village council, which took care of the issues within our community, and we mostly regulated our own affairs even at the regional level.

At home we didn't have any books except for the Bible, which is why my parents were unable to read or write very well. There weren't many other distractions in the house either, and so we played most of the time outside, weather permitting. Our toys were very simple. For example, the heads of the girls’ dolls were made from bottle gourds, painted by our grandmother and they were dressed in clothes made from old curtain fabric or whatever else was available. The dolls were really pretty and their pumpkin heads could withstand quite a lot rough treatment. Grandmother Marga gave me a little bear made of burlap and stuffed with straw, which I always kept under my pillow. Despite our simple circumstances, we felt we had a wonderful childhood.

Ivanda was a small village with about three hundred inhabitants. Like all villages from the time of the immigrations, the sandy streets were arranged like a chessboard, and each house had a courtyard and a large vegetable garden. When it rained hard the streets would turn into a brown sea of mud. What remained after the rain were huge, deep puddles and a wonderful smell of rain and wet ground. These puddles often lasted for weeks and were populated by fat, green frogs, and catching them was great fun. Afterwards we were always covered in mud and had to go for a swim in the village pond before we dared to go home.

Our house was typical of our village. There was a ground-level living area with the kitchen and the living room, where almost everything happened. Then there were the bedrooms, of which we had too few. For this reason, the younger boys, Jacob and Matyas, had to sleep in the living room, while my brother Nicolae and I shared a room, as did my sisters Lissi and Leni. Attached to the house was the pigsty and under the roof was the pigeon loft. When it was quiet in the house, the deep cooing of the pigeons was a constant companionable sound. However, complete silence only really occurred at night, when the pigeons were equally asleep.

There was also a small cowshed with a hayloft and a thatched roof. Everything was built around a courtyard, partly covered by grape vines, which doubled as our bathroom. There was a zinc tub, but most of the time this leaned against the wall of the house in a corner. We didn’t bath very often because this involved heating a lot of water. Instead, we usually washed ourselves using the pump in the courtyard next to the well, but even in summertime the water was very cold. However, grandma, mum, Leni and Lissi washed themselves in the house using a bowl of warm water. Our toilet was behind the cowshed. During the warm seasons it was tolerable, although the flies were a real nuisance, but during winter it was uncomfortably cold so one had to follow natures call in a hurry.

From todays material point of view, we were actually poor, but as children we didn't really know this and were just happy. Our parents always reminded us how much harder it had been for our ancestors in the 18th and 19th centuries. They told us: ‘The first had death, the second had hardship, the third only had bread.’ This saying was deeply rooted in the collective memory and described the living situation of the settlers who had migrated in the 18th century to the then swampy Banat, which was still plagued by occasional Turkish raids.

The community had its own German school in the village, but we didn't always have lessons. We had more classes in winter but none at all during the harvest season. Then we had to help in the fields from an early age and didn’t have much time for school. However, now and then the Romanian school authorities gave us warnings as to not neglect the children’s education.

As a boy, I was always outside in the gardens, in the fields or fishing from the banks of the Temesch, the big river not far from our house. I used to hang around with my friends, Sepi Horti and Karl Follmer, during the holidays. Sepi was not one of us. He was a Serb, but this didn’t bother us, of course. Only my father Nicolae didn’t like him very much. He wanted us to keep to ourselves and only work together with the Serbs and Romanians when it was absolutely necessary. He also thought that the ‘lazy Serb’ prevented us from working. Everyone was expected to pitch in and not just enjoy themselves. This was his simple philosophy of life – pray and work – almost like in a monastery. We only found out later that he also had other pleasures.

During my early childhood we did not have a horse to work the fields. Only an ox. It was quite old and, in contrast to us, quite fat. My mother Roza was often desperate to feed her brood and scolded me every time I tried to run away instead of helping in the gardens. But she was a good woman – firm but also fair – as one had to be with a herd of six children. Although we had to work, there was still time to roam around.

In 1932, autumn arrived early and it became pretty cold. Nevertheless, on a slightly foggy Saturday morning I decided to go fishing at the Temesch. I had already caught a few small fish when there was a crackling noise in the bushes behind me. I looked around but couldn’t see anything. Then there was a loud rustling sound nearby and the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. I grabbed my fishing knife with my right hand and the club with which I killed the fish in the other and walked slowly towards the bushes. Suddenly a small furry face appeared. I screamed and jumped backwards, but it was only a young brown bear who was now pushing its way through the undergrowth, approaching me curiously. I immediately remembered my father's warnings. Where there is a little bear, the mother is not far away. Normally there were no bears in our area. They stayed in the mountains, but the early snow could have brought them here. The little one was standing in front of me now but I couldn't hear any other sounds. Maybe it was alone? But bears can also be very, very quiet, my father had said. Carefully, I held one of my small fish out to it. Amazingly, it came right up and grabbed it. It seemed to be completely starved. The fish disappeared immediately so I held out another. It took that one too. What to do? Maybe it wasn’t wild at all, but had escaped from somewhere? Hence, I decided to take it home with me. I held it carefully by the neck and with a fish in front of its nose, I lifted it into my cart and put it next to the bucket with the catch. It eagerly helped itself to the fish on the way back. There was probably not going to be lunch from the Temesch catch today. In the village, people were amazed when I rolled through the streets with my new companion. The bear seemed to enjoy it too, sitting there looking around with wide open eyes. The bucket was empty by now and its belly was obviously full.

When we got home, my dad looked at me with wide eyes too. Surprisingly, he reacted quite calmly, which did not happen very often with him.

"Where did you find this?"

"It found me by the river,” I explained. “It was all alone so I fed it and then took it with me. Can I keep it dad?"

"A bear like that needs a lot of food, Ioan, and he’s going to get a lot bigger,” he replied.

"We could build a small stable for it and I would get its food," I said.

I looked at my father with pleading eyes and it was one of the rare moments when I could catch something like true warmth in his gaze. I knew then that I would get to keep the bear. At least for now.

"What should we call it then?"

"Paul!" I said off the top of my head.

"Is it a boy?" dad asked.

I hadn't thought of that. But my father grabbed it and cleared it up on the spot. It was a Paul. Now my brothers and sisters came out of the house and gazed in amazement at our new family member. Paul was led into an empty pigsty and we went into the house to eat. We were not even properly seated at the table when there was a terrible whining sound outside. Paul didn't seem to like being in the pigsty at all. After a while, the howling got on my parents’ nerves too and so the bear was allowed out of the pigsty. This seemed to calm him down, except that he began following me wherever I went. Eventually, of course, he followed me into the house, where he went into a corner and took a nap. There he stayed and from then on became a real pet.

Paul was a clever bear and quickly figured out whom he had to charm in order to secure his stay in our house. Although I was the one who made sure there was always enough for him to eat, he seemed to be particularly fond of my father. When he came in from the fields, Paul would be waiting at the gate to greet him, much to the dismay of our dog Asta, although she, too, came to terms with Paul’s presence. Inside the house, he would lie at my father’s feet under the table, growling contentedly. He behaved just like a dog. My father didn’t really let on how much he liked it, but displeasure at this disloyalty was written all over my face.

Paul was also docile and trainable in other respects, so I taught him how to dig up potatoes. With his strong claws, this was easy for him. Of course, he was only after the food, but since I was present, I could always pull him away and collect most of the potatoes, while he had to make do with one or two. In this way he helped me in the garden and at the same time reduced the amount of work I had to do to get him food. Of course, my father didn't like this at all, as he would have preferred to see all the potatoes going into the cellar. Hence, we shifted our tactics to going to the church fairs in the many small surrounding communities. My father put a device on our bicycle for this purpose so I could attach the handcart and ride off with Paul in tow. As he was a very good-natured bear, I would sit with him at the edge of the market square and whoever wanted to – and dared to – was allowed to cuddle him for a few minutes after paying a few bani to his caretaker. This business went quite well. As he was not wearing a muzzle and was now almost fully grown, it became a bit of a test of courage, especially for the young men who wanted to show off in front of their girls. I also took a small bag of potatoes with me and whoever paid was allowed to put one into his mouth. That was only for the very brave. We all had fun and when the weather was good, we made a few lei by the end of the afternoon. Then we packed up and cycled home. I was very proud of the money I earned and was allowed to keep some of it, while the rest went into the household kitty. We did this every weekend in late summer until the church fairs were over. Unfortunately, we were able to do this for one season only, because Paul grew steadily and became heavier and heavier. Although he could still fit into the handcart, I could barely pull it with the bike, let alone slow it down, so we had to give up this side-line.

One sultry summer afternoon, when I was about 12 years old, my friends Sepi and Karl came over to our house. We were hot and bored and were sitting in our courtyard in the shade of the grape vines when my mother left the house. Grandma was taking her afternoon nap and my father was fishing with friends at the Temesch. Paul was also lying in the shade, dozing off. I had been wondering for some time what might be behind the small door at the end of the hall, especially since my parents always kept it locked and when they opened it, they made sure that none of us were in the room. As there was nothing else to do, I went into the house and took a closer look at the door, sniffed at the keyhole, and thought I detected a faint fruity smell. It was a regular lock so I went over to my father's workshop, got a nail, clamped it in the vice and bent it with the hammer to make a lock pick. Then I hammered the tip a bit on the anvil and my key was ready. I had seen my father do this a few months earlier when he could not find the key to the shed. The makeshift key quickly went into the lock. I turned it once and the door immediately opened with a slight click. I carefully pulled the door handle and looked into a small shed containing several large glass jars of cherries and plums. They looked excellent and as I felt hungry, I took one of them out into the courtyard. My two friends were looking at me expectantly and their eyes widened at the sight of the fruits. We took off the lid and each one reached into the jar to take out a handful of cherries. They smelled a little strange but not unpleasant. Although they tasted a bit sharp and tangy, they were good and everyone wanted more. I was afraid that my parents would notice that the level of cherries had gone down so I closed the jar, took it back into the house and got another one. Now we could have some more. From then on, the situation began unravelling as a result of the pickled fruit. First Sepi started to giggle, which was contagious, and Karl and I followed suit. Then he started to laugh and we both couldn't stop ourselves: we laughed so hard that we could hardly breathe and our stomachs began to hurt. For a moment I thought I would suffocate. Once our laughter had subsided, I began to feel very hungry.

"I could eat something now," I said in a slow strange voice.”

The other two looked at me and burst out laughing again.

"I'll go and catch us a pigeon," Karl said.

He stood up and immediately fell over again. We looked at each other in disbelief and started laughing again. Now all of us tried to get up but we could only crawl towards each other. Then the three of us staggered across the courtyard towards the pigeon loft, falling down several times and laughing our heads off. Finally, we managed to climb the small ladder to the loft above the kitchen. We pushed the door open and fell into the pigeons’ home with such a roar that all the birds fled. What we hadn’t taken into account was the thin reed mat ceiling above the kitchen and so the inevitable came to pass: the ceiling collapsed under our collective weight and we took it with us as we fell onto the kitchen table. I had just begun to realise that this had been a bad idea when my father came into the room. I can still see his face, which immediately swelled and began to glow red. He grabbed Sepi and Karl and threw them out through the open window. While I heard their cries of pain, he grabbed me by the collar, seized a piece of firewood and beat me savagely. I screamed, tore myself away and dived under the table. He was so enraged, however, that he yanked me out again by my legs and continued to beat me.

"I'll kill you, you bastard. You useless, good-for-nothing scumbag! You miserable snot-nose," he screamed.

I screamed too and thought he was really going to beat me to death. Fortunately, amidst of all this, my grandmother appeared, snapped my father's raised hand, and said in her calm, dark voice: "Nicolae, stop it, you're killing the boy."

When he now let go, my whole back ached and burned like fire. Eventually I crawled out of the kitchen into our bedroom and I heard my grandmother say: "It’s all your fault, Nicolae. Why didn't you lock the liquor cupboard?"

I heard my father's stomping down the hall and slamming the door loudly into the lock. Then there was silence and I lay in our bed crying myself to sleep. Dad would never learn from me that the door had actually been locked.

I didn't notice any of the tidying up that evening and when I awoke the next morning my brother Nicki was already up. Now not only did my back hurt, but also my head. It was buzzing so badly that I could lift it only a few inches at a time. When I was finally on my feet, I shuffled into the courtyard and pumped the cold well water over my head. That felt good. My mother came out of the house and looked at me. Then she said, "You've created a nice mess here, Ioan." She looked me over again, put her arm around my shoulder and led me into the house. I have never forgotten that touch for the rest of my life.

Inside the house, the kitchen was clean again. The hole in the ceiling had been provisionally covered with an election poster of the National Peasants’ Party. Elections were quite frequent in Romania. Not least because the king had parliament dissolved whenever he didn't like the politics. My parents were rather apolitical people and I wondered why they hadn’t just stuck the front of the poster against the ceiling. This way, however, the party candidate would probably watch us eat for a while. Now we could hear the cooing of the pigeons better, I thought, but I couldn't laugh about it. My father came home for lunch and didn't even look at me. His anger seemed to have subsided but I felt he was not finished with the matter. Talking was not his forte so he did not warn me to keep my hands off the jugs in the future – but there was no need to, I already knew this.

My own misery and my aching back and head kept me busy all day, but I enjoyed the attention of my siblings, who kept trying to cheer me up. It was starting to get dark when I remembered that I hadn't looked after Paul, let alone seen him. Oh my God, how could I have forgotten him? But where was he anyway? He could have turned up long ago if he were hungry. He wasn’t in the house, so I went out into the courtyard and looked around, but he was nowhere to be seen. I wondered if he had gained access to the vegetable garden in his distress. That would cause a lot of trouble again. My back was already hurting again. I opened the gate and went inside the garden. It was huge, but so was Paul and I would have spotted him immediately if he had been in it. I walked on, but everything seemed normal. No plants had been trampled or rummaged over. But where was my Paul? A lump rose in my throat. What had happened? He certainly wasn’t here and so I ran back into the yard. My heart was in my mouth. In the cowshed – nothing. In the pigsty – nothing. In the shed – nothing. Nothing, nothing, nothing! Where was he? I had a terrible premonition, but what could I do? I ran into the street, asked the neighbours, all the people I met. Everyone in the village knew us by now, but no one had seen Paul. It was getting dark and I returned to the house. My father was sitting at the table.

"Where were you?" he asked.

"I was in the village looking for Paul, but he is nowhere to be found,” I answered.

"Maybe he was hungry, you neglected him today. He probably went looking for his food somewhere else. That’s what happens when you don’t do your chores," he said.

He didn't look at me and continued to spoon soup into his mouth. I didn't know exactly what had happened, but I knew that he was lying. He had something to do with Paul's disappearance. It didn't seem to bother him in the least that he was gone.

Paul would never return and from that day on I hated my father with all my heart. Despite this rift, I could not imagine leaving this family circle for a long time and yet things happened that made this inevitable in the end.

GROWING UP

When I turned 14, I finished school and was apprenticed to the butcher, Mats Kandler, in Johannisfeld. He was also the local headman and a distant relative of my mother’s. I was supposed to learn a trade because according to our so-called Anerberecht - the right of inheritance - only the eldest son, Nicolae, would inherit the farm. The rest of us had to find a livelihood elsewhere. My parents thought that becoming a butcher was the right profession for me, but I didn't want that at all. I had completely different ideas about what I would like to do, but of course I wasn’t asked. Because I lived in the neighbouring village, I didn’t have to stay overnight with my master. On the one hand, this was good because I wouldn't miss my family but, on the other, it meant getting up very early every day and walking to Johannisfeld, whatever the weather. This could be an arduous undertaking, especially in winter, when there was a lot of snow. I was also not keen on slaughtering and processing animals. I rather admired the drivers of the big machines and lorries that occasionally roared through our village in a huge plume of dust. To me they were the real guys and I would have liked to do something like that. But I had no choice. What else could I do here?

The way to Johannisfeld was long and even if I walked at a brisk pace, which was almost automatic in the winter cold, it still took me over an hour. In summer I was often allowed to use our bicycle, which made the commute easier. It was also daylight by then and I didn't have to be so afraid of wolves. Of course, there were no longer wolves in our valley, but the old people kept on telling stories from the times when the wolves visited regularly in winter and those had left their mark.

One dark wintery morning, the snow crunched softly under my boots and I saw shadowy figures behind every tree. However, when I paused, there was no sound other than my breath; just absolute silence that sang very softly in my ears. My heart then sank to my boots. Some mornings the sky was clear and an icy wind swept across the flat land, freezing the snow. Every step I took was so loud that the distant dogs barked and I was always very relieved when I finally arrived at the butcher’s shop.

Of course, as an apprentice one doesn’t only learn the butcher's trade. Most of the time I had to clean up or I was even sent to the master’s fields to help out. I was often so exhausted by the evening that I walked home with difficulty and fell into bed right after supper. My only free time was at weekends, but even then, we all went to mass in Johannisfeld, Sundays. I have no idea how many times I made this commute, but with this routine my apprenticeship years just flew by.

Kandler Mats, as everyone called him here, was not really a bad person. Of course, I got a few slaps once in a while when the intestines burst as I was making sausages. But that was all right: the matter was settled and no one bore a grudge. Kandler didn't pay me any money, but I was allowed to take home a big packet of meat and sausage every Friday. All of this usually ended up on the family dinner table, but after a while I started to set aside a few of the dry sausages and once a month I would take them to the weekend market in Schebel and sell them there. Schebel was almost 20 miles away, but the market was quite large and at least it was far enough away from home so that no one recognised me there. Never before had I been that far away from home on my own. Since the visits to the fairs with Paul, this was the first opportunity I had to earn some money again. I often looked around furtively to see if I could see Paul in a garden, but of course he wasn't there.

Although my father constantly asked what I was up to on Saturdays, I persisted in keeping quiet. After a while he stopped asking and I was able to go about my business undisturbed. In this way I built up a small nest egg. As long as I put enough sausages on the table, everything seemed to be fine.

Kandler's family was smaller than ours – only two children – but they lived in a much bigger house than we did. Since I sat at their table at lunchtime, I naturally got to know them all. He had three daughters and I liked the middle one, Hilde, from the first day I met her. During lunch there was silence at the table after prayer but when the meal was finished, there were always a few minutes before we went back to work. Then Hilde and I would sit on the veranda steps and talk. I told her about my bear Paul and all the things we had done together and the parish fairs where we had performed. Hilde actually remembered seeing us there once. My heart immediately leapt at the thought that she could remember me, or rather Paul and me, and despite my tiredness that evening, I could hardly fall asleep. I adored Hilde and she returned my glances but, of course, over time nothing ever happened.

On Saturdays I also used to meet up with Sepi and Karl. Karl had not yet found an apprenticeship and continued to work with his father. Sepi was in a similar situation as me and had started working with a tailor in Djulwes. He also had a long way to work, but he had his own bicycle, which made things much easier. He seemed to enjoy the work so much that he also sewed things in his spare time, mostly dresses and blouses for his siblings. It was a mystery to me how a boy could enjoy making clothes, but Sepi even tried them on in front of us and admired himself in the mirror. I thought this was a bit strange, but Karl clapped his hands and we knelt down beside him and sang ‘Ein Männlein steht im Walde’. Sepi danced around like a dervish while we tried to lift his skirt. This went on until we could laugh no longer.

In summer we also had a meeting place next to the Temesch river, where it branched into a small side stream that was almost completely overgrown with reeds. This place could only be reached via a narrow path that led down to a half-ruined jetty, which could no longer be accessed by boats. Here we had built a shelter with a bench out of old wooden boards. We met there one day to smoke cigarettes and looked at pictures of naked women that Karl had brought with him. It was here that I had my first erection. I was so confused by what was happening to me, and afraid that something was wrong, that I pulled my penis out of my trousers and showed it to the others. Karl followed suit.

"That's quite normal,” he said. “It often happens to me in the morning, but it goes away again. But when you do this," he said, and he massaged his dig, "it feels quite nice at the end."

I stared in disbelief at my erect penis. Sepi kept his in his pants.

"Come on Sepi," said Karl, "let me see it."

Hesitantly Sepi took out his penis. It was totally normal – small.

"You don't like the girl pictures, do you?", said Karl, emphasising the word girl.

Sepi turned bright red and hurriedly put his penis back into his pants. I did the same. I didn't feel like playing with myself here in front of the others. Karl, however, continued. His hand sped wildly back and forth until he collapsed with a loud groan. There was a slimy liquid on the back of his hand. I found this disgusting and stood up.

"I have to go guys. See you another time." However, on the way home, I couldn’t get this out of my head.

The next morning – my brother was already up – I turned onto my side, took my penis out of my pyjama pants and reimagined the pictures. Immediately I noticed something beginning to happen. Now I followed Karl's example, only a little slower. My penis became thicker and firmer. I massaged it more quickly then suddenly I knew what Karl was talking about. Something seemed to explode and I had a wonderful feeling between my legs. I moaned softly, but then it was over and I felt that my hand was wet. From that morning on, whenever I could, I tried to get up after my brother.

Shortly before my 18th birthday, my apprenticeship came to an end. I still would have liked to do something other than butchery, but there was nothing else for me in the Banat other than working as a farm hand or a day labourer. I might have been able to find something in Temeschwar, but I had never been there for more than one day and didn’t know my way around. Anyway, the thought of going there made me very uncomfortable, besides which there was also someone I didn't want to leave behind. Over time, Hilde and I had become friends and we always went to the festivals in our villages together. The ones in Johannisfeld were bigger and more crowded than the ones in Ivanda, but the latter were also big events for our entire village. Everyone helped with the preparations, which in itself was a lot of fun.

In January, there was Swabian Day, when we commemorated our origins. In May there was the traditional Maypole Festival and in late summer, the Kirchweih, if your village happened to have a church. Ivanda didn't have one, so we went to Johannisfeld for this celebration. On these festive days, everyone put on their best clothes. The women and girls wore their traditional costumes with colourful aprons and braided hair, and the men wore their suits and hats decorated with paper flowers and long white ribbons. The band played and everyone took part in the procession which went around the church and then on to the market place. Not only was it one of the few pleasures in our otherwise busy but rather humdrum lives, it was also one of the few occasions when unmarried men and women could touch each other in public without incurring the displeasure of the elders. Of course, this happened only at the dance or at the aforementioned parades. However, Hilde’s father could not tolerate this either, so when we were in Johannisfeld we could only stand next to each other. In Ivanda, however, we held each other’s hand the whole day long. This made my heart almost leap out of my chest with happiness, as I was so pleased that I had won Hilde’s affection.

When I finished my apprenticeship, Mr Kandler asked me if I wanted to stay on as his assistant. Although I didn't particularly enjoy the job, I liked the idea of being able to stay close to Hilde. The prospect of finally earning my own money without having to secretly go to the market also suited me very well, so I agreed. I had already bought my own second-hand bicycle from the proceeds of my sausage sales, so the journey to Johannisfeld was no longer so arduous.

Mats Kandler sometimes appeared grim and often shouted at his apprentices, hence I was glad that I was now in a somewhat different position. Although he often scolded me, he seemed to like me, or he wouldn’t have asked me to stay on. His wife Maria was kinder and ran the weekly bread baking in the community bakery. I believe she liked me too, because when we sat together at lunch, she always put an extra ladle of stew on my plate. Or perhaps she just thought she needed to beef up a skinny as I was 1,75 metres tall, but weighed only 60 kilograms. Anyway, I learned from Hilde that her mother also knew that the two of us were fond of each other and it seemed she didn't object.

Unfortunately, this didn’t apply to Mats Kandler. For a long time, I had no idea why he disapproved, until I overheard a conversation. I had been working as a journeyman for over a year and had been allocated a small room in the house in Johannisfeld. In winter, the route from Ivanda was very difficult and sometimes impossible, especially with a bicycle. Either I sank into the mud and was filthy when I arrived or I got stuck in the snow drifts. This meant that I often arrived late and then had to listen to my boss grumbling all day. At some point, Mrs Kandler, who had been noticing the whole thing, offered me a room under the eaves, which I gratefully accepted.

My mother cried when I packed up my bundle the following weekend, but my father just told me not to do anything stupid. I wondered what he was alluding to. Anyway, he grinned and I felt the aversion that had been building up in me for a long time dissolve a little bit. Some of my siblings were not at home. Jakob worked in a shop in Timisoara and it was much too far to commute on a daily basis, so he no longer lived at home. He was happy to have his own room in the city and not have to sleep in the living room any longer. Matyas was certainly looking forward to taking possession of my bed. We all kissed goodbye, the girls – by now young women – cried and I cried too and promised to come by regularly. It was almost as if I were moving to Bucharest, when it was actually just around the corner.

I settled into my new home and enjoyed not having to spend two or more hours on the road every day – time that could be used far more pleasurably.

Meantime, Mats Kandler had bought himself a car and on Saturdays he drove to the weekly markets to do additional business. This was when Hilde would slip into my chamber and we would kiss passionately and hold each other close. I could have lain here like this for days. Of course, I knew that one day her father would find out about us, but I hoped he would simply give us his blessing. However, this shouldn’t be the case.

One morning I was working in the freezer when Hilde came into the shop. The door was ajar and so I could hear her say, "Dad, I'd like to go to the Kirchweih in Neuburg with Ioan tonight. Would you please take us there in the car and fetch us afterwards?” At first there was silence, then I heard Kandler puff.

"Listen Hilde, I would drive you to Neuburg, but only without that guy from Ivanda. You understand? Put the Grosz out of your mind. He’s not good enough for you. He has nothing and his family has nothing. What do you want with a guy like that?"

There was dead silence in the shop. My heart was in my throat and my knees became weak. I thought I would sink into the floor. Then I heard Hilde sobbing. Her quick footsteps clattered on the tiled floor and then the door was slammed shut. Silence again, except for the panting of old Kandler, which had become more violent. By now I had slid down the wall and was holding my knees. I was cold because I was freezing from the outside as well as from the inside. I only hoped that the Kandler wouldn’t find me like this. The shop would open in half an hour but by then I had to get out of here. It felt like an eternity before he finally shuffled out of the shop and I heard the door close again. I waited a few more minutes, then carefully opened the door and slipped into the salesroom. I unlocked the door and stepped out into the street where, unfortunately, I ran into Kandler. He stared at me in disbelief.

"Where do you come from?"

I felt the blood rush to my face. "I thought I would open the shop."

"But it's still a bit early, isn’t it?" he replied, and continued to stare at me.

"Yes,” I said, “so I shall just shut it again." I turned and went back into the shop.

"Ioan!" he called. "Watch out!" Then he ran back to the house and disappeared through the front door.

I was totally miserable. I didn’t know where to put my trembling hands. I would not want Hilde to see me like this. I crept up under the roof and lay down in bed. He knew that I had been listening and this was not good at all. I should have made myself heard somehow – knocked over a bucket or something – then those words might not have been spoken, at least not in my presence. Yet this would not have made any difference.

That day I didn’t go downstairs again. When Mrs Kandler came up and knocked on my door, I just told her that I wasn't feeling well and couldn’t eat. I really couldn’t have touched any food. I would have liked to take Hilde in my arms, but she didn’t come up to see me. Sometime during the night, I fell asleep. But nothing would ever be the same again. I guess I grew up that night, but it didn’t feel good.

The following morning, I went back to work as usual. Kandler also acted as if nothing had happened. I was quite happy about this and didn't say a word either. It was obvious that I could no longer stay here and I had trouble holding back my tears of anger and disappointment. At lunch I finally saw Hilde again. She had stayed indoors all morning. Everyone was sitting around the table in silence, except for Matyas, who talked non-stop about his first ride in his dad's car. Apparently, he hadn't noticed anything.

After supper I went out to the vegetable garden. A short while later I heard the door. It was Hilde.

"Ioan, you know I don’t think like that." She obviously knew that I had overheard the conversation. "Ioan, I love you – but I can't go against my father either."

"I love you too Hilde, but I don't know what's going to happen now. He will not tolerate it and I will have no place here from now on either. I'm afraid I have to go."

We embraced each other and Hilde sobbed softly, but I had no more tears left in me.