2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Story Prism Studios

- Sprache: Englisch

Jinniyo

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Jinniyo

About The Author

Copyright

Jinniyo

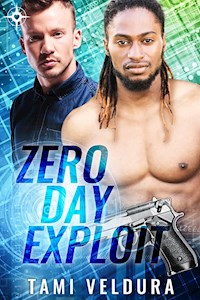

By Tami Veldura

On the Eastern coast of the Irne Desert, on the northern tip of the triangle-shaped city of Taulut, Devi Pruya buried her dark, bare feet in the still-hot sands just outside her diya’s winter home. For months the clan had wound their way down from the mountains into the migrating dunes and across the scarred face of the land to arrive here at Taulut to trade myrrh and gossip with clan Meka, who lived here year-round. The city’s fine sandstone buildings, set in tessellated triangles, stood sentinel against the salty ocean; a world without water at their back and a world full of it at their front without a single fresh drop between them.

Devi let the hot sand filter down between her toes, listening to the laughter and tittering of the meeting inside, two diya gathered for the evening to share family histories and old tales the night before jinniyo. It was rude of Devi to step outside during the tellings but it would be worse for her mother to fetch her. Her mother was the keeper of their history, from their small diya up through the larger clan Okso, to the very Irne People. Rawena could recite all of the large myths: the birth of the people, the breaking clans—but she also kept the smaller stories. The tales of Devi’s great grandmother and twice great grandmother and all the grandmothers before her.

Devi had no interest in the histories. What good were the stories of the past if they couldn’t help with the present? Rawena’s favorite, the legend of Estelle who first birthed the people, spoke of the woman crossing to the spiritual plane and blessing her children with the touch of the djinn. Devi hadn’t met anyone who could commune with the djinn. They were wild, aggressive creatures that seeped into the Irne Desert from the parallel spirit plane and nothing more. They harassed the caravans on the brightest full moons, dragging warriors away to who knows what torturous fate. No one wanted to have the touch of the djinn, and the story certainly didn’t help their clan cross the desert twice a year. Only the strength of their warriors and the Sight of their matriarchs truly kept them safe.

Besides, there would be plenty of tellings during jinniyo tonight when the spiritual plane and this one touched just briefly at midnight.

So rather than sitting in the telling circle, watching her mother step through the story, her voice dictating, her arms encompassing the world, her body moving into the legend, around and around the circle until the telling was told—rather than watch another history that couldn’t save her people, Devi stood outside the sand-scoured house in the red-dying sunset and took a breath of salt-speckled air, wondering what it would be like to train as a warrior.

The warriors knew how to fight against djinn, how to predict their attacks and sweep them away, how to work together to send them back into the spirit plane where they belonged. Some soldiers took Rawena’s anointment before the fight, a protection against djinn and a blessing. But soldiers anointed and not were both taken in equal measure. Only training and discipline and a nice sharp billaawe could save a life or defend the diya. Devi didn’t have training or discipline, but she did keep a billaawe tucked into its sheepskin sheath, its three-horned pommel wrapped in a blue and yellow headscarf that wouldn’t be missed, hidden at the bottom of her trunk.

If her mother knew… Devi hadn’t been told directly that she was favored to follow in her mother’s footsteps, keeping the histories of the Irne people, the diya was probably afraid she would run away if they said something so bold, but she knew that was where her mother and grandmother wished to see her develop her talents. She knew in the way Devi was always chosen for the two-person tellings despite having three sisters and a brother, in the way Rawena pestered her for the details of her day or the stories she’d seen out in the city, in the way her ayeeyo asked in the late dawn when the rest of the diya slept if Devi had cultivated the stories in her stomach where stories were brewed and condensed them into a fine thread so they could be woven into headscarves and sarongs with the telling.

Devi curled her toes in the sand, the soft particles already cooling with the dying sun. For all the heat of the day, the desert became a chilly landscape as soon as the sun kissed them goodnight and gave way to the moon. There was no heat like the desert heat. And there was no chill like the desert chill. It was fitting the two would be married so closely that they transitioned in a few breaths.

In the sand-softened wooden home behind her, Devi heard the telling come to an end. Now that the sun had fallen it was time to prep for jinniyo—the touch of the spirit realm—and finally a task fell to Devi that wouldn’t involve stories or telling, but a search in the desert.

She turned to face the home as all eighteen members of diya Fassi spilled into the sand like dark grains themselves, wrapped tightly together in each other such that the compact space of the house, or the litters of the caravan, were no concern. All Okso children learned to share tangled space from the beginning, everything belonged to all people.

Devi couldn’t remember when she first felt confined rather than protected when surrounded by the diya, and the rolling sensation in her gut—a sense of guilt—had been the only thing she’d ever cultivated there. She bowed deeply to diya Fassi, hoping to cover her earlier impoliteness and their ayeeyo nodded her covered head in return as they moved into the deepening darkness. Already, lamps and string lights were dotting the city and Devi’s guilt churned into anticipation.