Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Clube de Autores

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

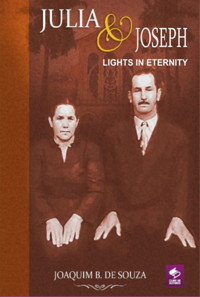

In an uncertain and turbulent historical milieu, the author revisits his childhood, a time when the boundaries between dreams and reality were hazy. Despite the difficulties of a society steeped in machismo and selfishness, he treasures the captivating memories of his youth. This nostalgic dive prompts him to recall significant moments with his parents, Júlia Prescedina de Jesus and José Honório Tristão, who faced considerable challenges to support a large family in the countryside. With a narrative brimming with emotion, the author imparts the lessons and experiences that molded his life and presents his parents journey as a testament to resilience and unconditional love. The account also illustrates the author s hope in articulating unexpressed feelings towards his mother, revisiting the complexities of his childhood and family life. Moreover, the book offers a critique of the Church s influence on family and societal life of the era, emphasizing how religious directives often dictated decisions regarding reproduction and family, in a context of growing demand for individual rights and societal changes. The author underscores the challenges faced by his generation, which was marked by a Church that sometimes-resisted emerging cultural transformation movements. Keywords: nostalgia, memories, longing, childhood, overcoming, brotherly love, period romance, politics, family saga, church, religion, Brazilian Novel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Joaquim Batista de Souza

JULIA AND JOSEPH

LIGHTS IN ETERNITY

©2017-2025

Copyright ©2017-2025 Joaquim B. de Souza

Layout and Review: By the Author

Cover: Alessandro Mattos

This work is a standalone production.

Work Registration ISBN Nº. 978-65-01-75119-1

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means—electronic, including photocopying, recording, or photocopying—without the author's written permission. Violators will be subject to the sanctions provided for in Law 5.988 of December 14, 1973, and subsequent regulations.

www.acleju.com.br

www.jbtreinamento.com.br

International Cataloguing-in-Publication Data (CIP)

Souza, Joaquim Batista de

S729j

Julia e josephlights in eternity: Joaquim Batista de Souza. -- 1. ed. -- Jussara, PR, 2025.

273 p. ; 21 cm.

ISBN nº 978-65-01-75119-1

1. Brazilian Novel – Family history rescue(1960). I. Title.

0423-16 CDDB869.3

Index for systematic catalogue:

1. Brazilian Novel B869.3

PREFACE

In an uncertain and turbulent historical milieu, the author revisits his childhood, a time when the boundaries between dreams and reality were hazy. Despite the difficulties of a society steeped in machismo and selfishness, he treasures the captivating memories of his youth. This nostalgic dive prompts him to recall significant moments with his parents, Júlia Prescedina de Jesus and José Honório Tristão, who faced considerable challenges to support a large family in the countryside. With a narrative brimming with emotion, the author imparts the lessons and experiences that molded his life and presents his parents' journey as a testament to resilience and unconditional love. The account also illustrates the author's hope in articulating unexpressed feelings towards his mother, revisiting the complexities of his childhood and family life.

Moreover, the book offers a critique of the Church's influence on family and societal life of the era, emphasizing how religious directives often dictated decisions regarding reproduction and family, in a context of growing demand for individual rights and societal changes. The author underscores the challenges faced by his generation, which was marked by a Church that sometimes-resisted emerging cultural transformation movements. Through straightforward and accessible prose, he reflects not only on the hardships of his childhood, but also on the oppressive climate of the 1960s, when the Catholic Church was regarded as a conservative force. Ultimately, these memories form a potent narrative about resistance, faith, and the quest for identity in difficult times.

“Hope is the sustenance of our soul, to which the poison of fear is always mixed.”

(Voltaire)

INTRODUCTION

In an era punctuated by destructive and dark events, the author, with his restless mind, chose to revisit a time when most people conflated illusion with reality. It is apparent, dear reader, that he never ceased to appreciate the wondrous and captivating experiences of his childhood, filled with joy and radiance. However, the passage of time revealed the damages of a patriarchal, sexist, and intolerant society, which rendered men incapable of acknowledging the rights of others amid selfishness.

The book mirrors the author's desire to journey back to the past, reliving experiences and reconnecting with significant individuals in his life. Nothing was overlooked, from the simplest memories to the hard-earned lessons. All these recollections contributed to his personal development! The author delved into nostalgia to reconnect with his beloved mother and express what remained unspoken. He revisited moments with his father, laboring with determination in the adversities of the field each harvest! Sharing these stories is inspiring and will pique the reader's curiosity to uncover the journey of Julia and Joseph, narrated through the eyes of a child, their eleventh child, in accounts rich with emotion and significance. However, he does so from the current perspective of a mature man.

Another aspect that greatly intrigued me, addressed by the author in this book, was the influence of the Church. How it intervened in family decision-making, including matters of human reproduction, impulsively and without birth control. I do not question these decisions, as the author is the eleventh child! His mother gave birth to eleven children at home, living in the countryside, during the thirties and fifties.

Hence, when the author decided to pen down his childhood memories to immortalize the life stories of his mother, Julia, and his father, Joseph, he hadn't anticipated the wave of nostalgia it would bring. These are tales from a tough yet enchanting time. Some memories brim with joy, while others are steeped in sadness and suffering. It's unfortunate that many of the little stories have faded from his memory, as he himself acknowledges. The book prompts profound reflection on human existence. His parents' journey is portrayed as an inspiring testament to resilience and bravery.

Amidst a sense of yearning, the memories of Julia and Joseph in 'Lights in Eternity' transport us to a tale of fraternal and affectionate love. Julia, the mother, devoted her life to her children, enduring eleven childbirths in her rural home. Joseph, the father, battled to provide for the family amidst economic, political, civil, and global conflicts. When Joseph was born, Brazil was a fledgling republic of just 21 years. The remnants of the empire were still palpable. The author shares his emotions about these loved ones, beginning from their transition to the spiritual realm, that is, after their passing.

The entire book is written in a straightforward narrative, shunning complex and formal language. The author deliberately avoids sophisticated or intricate terms, which could appear pretentious, given the simplicity of his characters. The events unravel in a simple yet imaginative manner. His objective was to reexperience his innocent childhood left behind. He sought to answer the question: how does a mother manage to birth and raise so many children in trying times?

The primary aim of the book was to reclaim childhood memories. If parts of his youth found their way into the book, it was either because they held equal importance, or simply because childhood stretched into later years during that era.

The narrative is set in a time when the rugged countryside man, the farmer in his purest form, had little comprehension of the world beyond. He dealt harshly with anything that exceeded his personal interests. These farmers were bereft of opportunities. Generally, they were confined by subservience and obedience to the Church.

In the 1960s, the Catholic Church was perceived as oppressive for several reasons. Among these were resistance to social transformations, as the church, being a conservative institution, frequently opposed the cultural shifts that were taking root during this time. Movements for civil rights, feminism, and an increasing quest for personal freedom clashed with the traditional doctrines of the church. Moreover, the church wielded significant political influence in various countries, often aligning with authoritarian regimes. In Brazil, during the military dictatorship (1964-1985), sections of the clergy supported the government, while others, like the progressive group led by Dom Helder Camara, resisted the repression and advocated for human rights. Another significant aspect was the moral control that the church exerted, shaping the morality and customs of society, something that was viewed as oppressive, especially among the youth and counter-cultural movements. The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) represented an effort to modernize the church, aiming to address criticisms. This event ushered in several changes, like the celebration of mass in local languages instead of Latin, and a greater willingness to engage in dialogue with other religions and contemporary society. Therefore, all these factors contributed to the portrayal of the Catholic Church as an oppressive entity in a time of intense social and cultural changes, mirroring the perpetuation of a patriarchal family structure where the male head imposed his will on all members of the family.

“History is a romance that happened; the novel is the history that could have happened.”

(Jules Goncourt)

CHAPTER I OVERVIEW

In the Unnamed Valley, an ancient sword lodged in the earth stands as a symbol of the events that have shaped its history. The valley, graced by a majestic river, merges the fruitfulness of the land with the melancholy of a troubled past. Within this setting, an Italian woman, bearing her sorrow and memories of loss, laid a red rose on a grave in tribute, forging a respectful bond with the local community. Italian culture interweaved with the daily lives of the migrants, particularly those fromthe State of São Paulo seeking new prospects in the coffee plantations. This new reality brought challenges, but also moments of joy during the harvest season. However, diseases and land disputes began to strain the harmony among the residents, escalating tensions. José Honório Tristão, a skeptical man from the State of Minas Gerais, started to observe shifts in community relations. Despite these disputes and the presence of an authoritarian patriarch, the pursuit of unity and cultural preservation remained prominent amid the hardships.

THE UNNAMED VALLEY

Picture an ancient sword, its long, sharp blade deeply rooted in the soil of an untamed grave. The sword, untouched by anyone's hand, could have been plunged into the chest of a crude caveman, a primitive prehistoric hominid, or a medieval man living in rough villages and towns, unenlightened and heavily influenced by religion and feudal totalitarianism. But no, this sword was thrust into the foul earth merely a few decades ago, by an unknown hand. It appears to have been driven into the mound of brown earth with fury, as a memorial or symbol of an ancestor. The metal stands in stark contrast to the dark and fetid soil around it, glinting subtly in the sunlight that breaks through the clouds. The soil is rich and teeming with life. Beside it, the expansive bed of the Dry Marsh River, where every inch pulses with the potential for growth, in front of the waterfalls. The land is profoundly fertile, enriched over centuries by sediment deposits carried by the meandering waters from the surrounding slopes. Visualize this grave on a mound of freshly turned earth, away from the water's edge, with sparse grass sprouting around it. A grave that could belong to any Homo Erectus, but it's far from that. It's the 20th century. Now, imagine a freshly plucked red rose, left on that same grave, as if forgotten. This unassigned mission involved a lady of Italian descent, who spoke with an accent and frequently used profanity. She dressed in a Neapolitan style (a nod to Naples, the city of 500 domes), despite never having visited. Her grandparents were the ones who immigrated to Brazil. This peculiar lady wore vibrant scarves on her head and a long, earth-toned dress made of coarse linen, with shades of faded brown. The billowy sleeves provided comfort for her arms, and she wore an apron over the dress to shield it from dirt during her work in the fields. On her feet, she wore leather sandals and cotton socks. Despite being seen by other residents of the plot, no one knew who she was. "The roses are replaced daily," the elders said. But the mystery remained: who was this lady? She could have been someone paying tribute to a lost love, a mad passion from her past, or a brave soul, commemorating the valor and commitment of the deceased: a husband, a courageous soldier, or a crafty man. Some of her compatriots recounted that during the ship journey, one of her children died on board. Despite her despair, the decision to commit the body to the sea was inevitable. In a humble and religious ceremony, the boy's body was wrapped in canvas and weighed down with stones to ensure it would sink. It was then cast into the sea, amid religious farewell songs. As a result, upon settling in the Nameless Valley, she buried her son's clothes as if his body were there. However, the mystery deepened when migrants from São Paulo, while venturing into these inhospitable lands, discovered that this eerie scene had been present in the heart of the native forest for many years, cohabiting with jaguars, ocelots, snakes, spiders, ants, and scorpions. "All are fabrications of these people," declared José Honório Tristão, one of the oldest residents and an explorer of the native forest.

The migrants from São Paulo hailed from far-off lands, forming part of an agricultural expansion initiative, primarily to engage in coffee cultivation. The Nameless Valley, the valley of coffee, was a prosperous prairie that had earned a reputation in the Southwest of São Paulo, from where most of the migrants originated. This region was populated through these migrations and expeditions that explored hills and plateaus. What they didn't initially realize was that they would be exploited, swindled by opportunistic "cats" who sold native forests they didn't own. However, they quickly organized and drove out these rogues, forming a prosperous plot with the finest coffee plantations, of the Sumatra variety. This variety, also known as Brazilian Bourbon, helped Brazil to establish itself as the world's leading producer. However, the downfall would come later, due to severe frosts and the onslaught of the pest insect, the bicho mineiro.

Women of Italian descent wore dresses made of light, durable fabric, suitable for hard labor under the sun. They adorned their hair with colorful scarves to protect it from dust and heat. Mrs. Júlia Prescedina de Jesus, the matriarch of the family of miners, viewed these clothes with skepticism. Meanwhile, Italian men typically wore long-sleeved cotton shirts and denim pants. Straw hats were common to shield the head and face from the intense sun. Others, not of Italian descent, wore hats made of tanned leather. Regardless of their origin, they all wore boots or sturdy shoes, suitable for the daily grind in the fields. "Always wear high boots, there are so many rattlesnakes, urutus, coral snakes!" — advised the matriarch.

Men and women of all backgrounds, their hands toughened by labor, skillfully and swiftly harvested coffee beans, navigating the coffee plants with a sense of familiarity. However, it took about three years to reach the harvest period, starting from the moment the seedlings were planted in damp holes covered with wood chips. Their faces, marked by the sun, heat, and dust, mirrored the determination and resilience of those who have grappled with the daily challenges of rural life since their arrival years ago. Life had been far from easy or luxurious. Each day demanded the overcoming of adversity. After all, they had left the lands of São Paulo, where their families were sharecroppers and tenants, to become landowners in this new territory. Despite the hard labor, fatigue, and exhaustion, a spark in their eyes revealed the pride they took in contributing to the harvest and supporting their families. During breaks, women would gather with their compatriots, sharing stories and laughter, keeping the Italian culture and traditions alive in their new home.

Other large families of Italian descent also made their homes in this valley, drawn to its silky soil, rich in essential nutrients that fed the eager roots of plants like coconut and oak trees. The top layers of the soil were soft to the touch, inviting seeds to be sown and sprout with vigor. Beneath the surface, roots intertwined in an unseen ballet of nutritional exchange, mutually nourishing each other and contributing to the vibrancy of the ecosystem. The color of the soil changed with the seasons, from a deep brown in winter to a reddish-brown in summer, reflecting its seasonal vitality. Yet, no matter the time of year, it always exuded a comforting earthy aroma, a testament to its organic richness. This fertile soil was not just a foundation for lush agriculture, but also a reflection of the harmony between nature and human labor. Skilled farmers from other regions of the country, and even from abroad, cultivated their coffee crops with respect and gratitude for this gift from the earth. In contrast to the vibrancy of coffee cultivation, a quiet and melancholic scene unfolded: a hill of freshly turned soil, with small mounds surrounding it, indicating a graveyard. "This valley is just beginning, and already so many have died from these damned diseases!" they lamented, referring to malaria, yellow fever, and tuberculosis, which were difficult to treat at that time.

At the base of the hill, numerous red roses had been carefully planted by a mysterious Italian woman on a piece of land abandoned due to its stoniness. The vibrant petals contrasted with the dark, moist soil. In the center of this hill, a freshly dug grave, yet without a tombstone, blended in with countless others, distinguished only by the loose soil surrounding it. And, in the center of this grave, an ancient sword deeply embedded in the ground, its long, rusted blade pointing towards the blue-lit sky. The handle, weathered by time, was partially covered with fresh soil, as if it had been placed there recently. This section indicated the native cemetery, although all who died were buried in this remote necropolis, regardless of their racial origin. Some were given full Catholic rites, while others were buried like animals without even a prayer for mercy, not even a candle was lit.

The golden afternoon sun could be seen gently bathing the scene, casting soft shadows around the hill. The silence was punctuated only by the gentle sway of the leaves and the faint rustling of roses in the wind. Despite the gruesome scene, it conveyed a sense of peace and reverence, a moment where nature and the past intersected in quiet respect. Workers were seen making their way home along the pathways after a long, hard day. Housewives were still picking sow thistles to serve as a side dish for dinner. Although it was an invasive plant with a bitter taste akin to chicory or spinach, it was vitamin-rich and served as a dietary supplement for rural families. The children were repulsed, but they had no choice, they were obligated to eat it.

In the Nameless Valley, families gazed out their windows, viewing the twilight as a sigh from nature. As the sun disappeared, the day's sounds gradually quieted. The wind whispered softly through the tree leaves, and the weary birds retreated to their nests. The crickets began their chorus amid the dewy lawn. The boys made every effort to locate the singing crickets, but the sounds they produced at night were directional, seeming to come from one corner when they were actually in another. The children always returned to their rooms in frustration. The onset of night stirred nostalgia in the families for their homeland, where they left their roots and relatives, saddened by the distance.

They all resided in the Nameless Valley, all from the same family. It was a serene and picturesque setting, where nature thrived. In the distance, green hills gently rose, covered by a broad, welcoming landscape, in stark contrast to the large coffee plantations interspersed among the 60-acre lots. In the valley's center, a wooden house with a sloping roof, built years before by José Honório Tristão, stood distinct from the other neighborhoods. The house was simple but not too small, accommodating twelve family members. It was well-maintained, as the patriarch was strict and would scold his children if they entered with dirty feet or shoes. The large windows let in an abundance of natural light. Surrounding the house were coffee yards, barns, granaries, pigsties, and corrals, along with a modest garden carefully tended by the matriarch, Júlia Prescedina de Jesus, a woman born in 1914 in the city of Salto Grande–SP, who had a love for roses and various other colorful flowers, as well as the vegetables that grew in well-defined beds. "It's a lot of work, but it's worth it," she would always say, tightly gripping the aluminum watering can as she watered. To fill the watering can, one had to first draw water from the well by hand, using a twenty-liter bucket hauled up by a windlass that creaked on its dry axle.

The family would always gather on the porch in front of the house: the couple, their adult children, and their little ones. During harvest times or significant weeding and clearing periods, neighbors would find a spot on the porch to discuss service day exchanges. Some would sit on wooden benches, others on the porch's edge, all while enjoying a cup of coffee. The family's matriarch, Mrs. Júlia, was always accommodating. As soon as the first visitor arrived, she'd set water to boil on the clay stove and prepare a generous amount of coffee, which she had roasted and ground herself. In this manner, her husband, Mr. José Honório Tristão, would offer the assistance of two or three of their sons to help a neighbor with a task requiring many hands. Later, the neighbor would return the favor, not with money, but through an exchange of manual labor.

During one of these tasks, Ziulso, a son of Mr. José Honório, met a 'giovane ragazza', a captivatingly beautiful Italian girl. It was a situation destined to fail: and it did! Back then, Italian-origin families would loudly proclaim their reluctance to mix with families from Minas Gerais, attributing it to the latter's laid-back nature. 'The world could be falling apart, and they wouldn't bat an eye', they'd say in disbelief. Consequently, the Italians were distant in their interactions with the people from Minas Gerais. You know the saying, 'the saint didn't hit'? Back then, the Minas Gerais family was seen as traditional and patriarchal, heavily influenced by Catholicism and conservative values, and as relaxed as they come! They were large families, and in agriculture, they were the main contributors to the family's income. Meanwhile, Italian families who immigrated to Brazil in the 20th century were industrious and close-knit, also heavily influenced by Catholicism and traditional values, and brought with them a wealth of knowledge from a developed Europe. How to understand this mistrust? 'I can't stand these polenta eaters!' José Honório Tristão would grumble upon seeing an Italian at work. Born in 1910, in Cariaçu, Minas Gerais, he was a stubborn man not easily swayed.

That day, he sported a straw hat, a checkered cotton shirt, denim trousers, short leather boots, a leather belt, and a scarf around his neck. He stood by the barbed wire fence near the orange tree that marked the boundary between the backyard and the pastures, tranquilly surveying the landscape and the cattle. Leisurely, he peeled an orange with his bone-handled knife. His primary concern was the jaguars - swift and stealthy predators notorious in the region for hunting calves. They resided deep in the forest atop the hills. When a jaguar attacked the cattle, it usually exhibited a typical predatory behavior pattern. This pattern was what the man from Minas Gerais, José Honório Tristão, sought to understand to gain an upper hand over the large cats and kill them. "I'll make a coat out of your hide yet, you wretch," he muttered, squeezing the already pulpy orange. The animal's meat was useless; it would be buried or left for the vultures. Upon spotting a jaguar in the area, he grumbled to himself, "Not again"! At the same time, Mrs. Júlia Prescedina de Jesus, clad in a floral dress with puffed sleeves and tight corsets, was busy plucking fresh apples from a nearby tree to make delicious preserves, while three young boys merrily played with a golden-haired dog, egging it on against the chickens and their chicks. Despite their mother's reprimands, they never heeded when it came to causing mischief. They had a habit of tormenting the animals. "Calm down, leave the animals be!" she would always chide.

In the afternoon, a soft sunlight bathed everything, casting long shadows that sprawled across the grassy valley floor. Close to the houses were the pastures, the corral, the cattle pen, and the pigsty. The lady of the house, with the help of her two young daughters, Anirde and Aira, produced cheeses, curds, and butter daily. At this moment, the blue sky was speckled with white clouds, adding a tranquil beauty to the rural vista. In the Nameless Valley, during these hours, the day's final lights gracefully yielded to the night in a display of subtle colors and delicate contrasts. The setting sun colored the sky with warm hues of orange and pink, which gently melded with the deep blue that gradually appeared. Illuminated by the last rays of light, the clouds took on golden and purple tints, reflecting the twilight radiance. As night fell, all creatures settled down: chickens roosted, cattle took shelter in their pens, pigs huddled in their pigsties. Ducks and turkeys stayed on the ground, beneath trees or granaries. Yet the noisy guinea fowls perched on the highest branches of the trees around the house, alert for the bush fox, a fierce hunter. Shadows began to stretch across the valley, blanketing the green, rolling fields. This was the time when the men returned from their work, either from the coffee fields or the white fields, depending on the season: wheat, peanuts, corn, or beans. The surrounding hills were silhouetted in shades of gray and dark blue, forming soft outlines against the colored sky. In the distance, solitary trees and small shrubs punctuated the landscape, their shapes becoming more distinct as the light faded.

In the heart of the valley, the Dry Swamp river meandered through the pastures, mirroring the last remnants of the sky's hue. The local boys, when not preoccupied with work or school, would swim in its waters. They were too young to toil in the fields, a task they loathed, but their parents were strict. So, whenever possible, they would fish, swim, and play in the water, much to their mothers' chagrin. The tranquil water reflected the sky's spectacle, creating an ethereal effect with its color gradient. The riverbanks were speckled with stones and wildflowers, their colors still discernible as twilight deepened. As night fell, the first stars began to twinkle, accentuating the soft hues of the sunset. The boys would excitedly exclaim, "The Three Marias", pointing upwards, only to be scolded by the adults, "Don't point your finger, you'll get warts." Such beliefs were ingrained in their folklore, a blend of cultural traditions influenced by Portuguese colonization, indigenous customs, and African heritage.

The valley gradually transformed into a sanctuary of tranquility, with the soft chirping of crickets and the fresh aroma of damp soil enhancing this magical twilight moment. Fireflies, with their intermittent glow, adorned the nighttime valley as they fluttered through the pastures. The adventurous boys would catch some and confine them in a jar to marvel at their glow in their dark rooms. However, deprived of air, the fireflies would perish - a mystery the boys couldn't comprehend. Nocturnal insects like moths, drawn to the light of lamps and lanterns, could be spotted landing on flowers to feed on nectar. Beetles, akin to scarabs, also shared the night. The valley exuded a sense of peace, harmony, and the simplicity of rural life, where the family lived in sync with the alternating rhythm of day and night.

The era was marked by misfortune. The restless minds of the people often blurred the lines between dreams and reality. The families of the Nameless Valley were minimally educated, with few able to write their own names. Yet, the enchanting moments they experienced under the influence of a euphoric and radiant shield were never overlooked. They led their lives to the fullest, albeit in a rustic, rural manner. However, the passage of years brought with it the harsh realities of a patriarchal, sexist, and intolerant society, which blinded men to their own selfishness. Violence, hatred, and a lack of resilience and compassion were the tools they used to assert their dominance. Neighbors respected one another not merely because they were Christian men, but out of fear of violent feuds. Yet, they could be stern when they deemed it necessary: "I don't want that little man from Minas Gerais in my house"! — was the rebuke of Figlia's father when she took a liking to Ziulso, the sixth son of José Honório Tristão.

In an era of totalitarian rule, marked by dominance and fear, the man with a totalitarian spirit always positioned himself above others, as if on a stage adorned with flags and symbols that elevated him. His imposing and austere demeanor revealed a stern and calculating man, with penetrating eyes that conveyed unyielding determination. A domineering villain, he never smiled. His hair was slicked back meticulously, adhering to the brillantine after each cold shower, lending him an air of strictness and control, underscoring his masculinity. An aura of authority radiated from him, augmented by the imagined presence of imposing bodyguards and servants surrounding him, all clad in rigid uniforms and maintaining disciplined postures. They saw themselves as heroes, but they were agents of chaos, in a mind that enforced its will through power. Around a totalitarian father, an atmosphere of fear and subservience prevailed, where subordinate figures bowed and awaited his commands in a blend of fear and coerced obedience. The surrounding environment could be familiar, yet austere, mirroring the display of power and the patriarch's detachment from his family's hardships. Concurrently, the Church's role was another crucial element in these people's routine, being strict and totalitarian regarding doctrine. Attendance at mass was compulsory for all Catholics, yet it was conducted in Latin, with the priest facing away from the congregation. Did anyone comprehend anything? Not at all! This cryptic ritual elevated the parish priest to an almost divine status. Nena, the youngest, José Honório Tristão, the husband, and Mrs. Júlia Prescedina de Jesus, the wife, separated upon entering the church. The youngest headed to the front bench to sit with other boys. The mother took a seat in the row of benches on the left, and the father on the right, thus they did not intermingle in the pews. For Catholics, the church was characterized by a classic design, with a grand altar and a layout that accentuated the divide between the clergy and the lay congregation. Communion was typically received kneeling, at an altar with a balustrade, segregating the sanctuary from the rest of the church. Communicants knelt and awaited the priest's rounds, receiving the host directly in their mouths. Beyond these dogma-enforced formalities, the clergy wielded significant influence on family decisions, including matters related to human reproduction, without any birth control, in adherence to official precepts and traditional Catholic morality. They guided families on family planning issues in various ways, excluding contraceptive methods. These prohibitions stemmed from the encyclical "Humanae Vitae", which opposed the use of artificial methods. This situation was tied to the belief that families needed to be large to provide ample help with manual labor, even though the Church perceived them as God's gift. The rationale for parents to have many children was understandable, with the aim of having plenty of hands to work the coffee plantations and to ensure their own survival. Only through divine enlightenment could one perceive the various facets of this world marked by imperialism. Truly, a journey!

José Honório Tristão, a man from Minas Gerais, and Mrs. Júlia Prescedina de Jesus, a woman from São Paulo, tied the knot on June 16, 1934, in the city of Ibirarema, São Paulo. The matriarch of the family, she brought eleven children into the world, one after the other, in her home in the countryside, with only a midwife's assistance, from the thirties to the fifties of the twentieth century! Each birth brought its share of pain, but also joy at the sound of each newborn's first cry, all of whom were born healthy. All were gifts of God. Indeed! These midwives, though without nursing or medical degrees, played a crucial role in facilitating home births. Mrs. Esmeralda, known as the 'holy hand', was renowned as the best midwife in the Nameless Valley. She had lost track of the number of births she had attended since her arrival in the region, braving forest trails and encounters with various animals and insects. She insisted that bullet ants, fire ants, and pixixica were more dangerous than many larger creatures.

Despite countless challenges, Nena, the youngest and eleventh child of the Tristão family, was a scrawny boy growing up in this Nameless Valley. From an early age, he learned to cope with the harsh realities of rural life. He observed a striking degree of intolerance among the families that had migrated from states like São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Bahia, as well as smaller numbers from other states, and those of Italian origin who found themselves in conflict.

Death, ever-present, hinted at matters far beyond simple religious beliefs. There was a strong faith in heaven, hell, and purgatory, but this faith did not diminish the desire for revenge when someone on their deathbed had been the victim of an ambush that ended in violence, whether due to land disputes or crimes of passion.

One day, Nena Honório Tristão watched curiously from the window of his house, taking in the details of a stranger. The man's skin was sun-tanned, his hair disheveled, and his beard unkempt. He walked among the trees near their home. Occasionally, the stranger would remove his straw hat to scratch his head, or roughly wipe his nose and spit to the side. Before unbuttoning the top buttons of his worn cotton shirt to cool down, he glanced at the window where the boy was peering. Startled, the boy quickly moved away. "Don't linger at the window," his mother scolded, before watching him jump onto the wooden bed covered with a grass mattress. The other mattresses in the house were stuffed with soft, rustling corn straw.

The country boy, blessed with innate farming talents, had a deep bond with the land and its creatures. However, in