Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

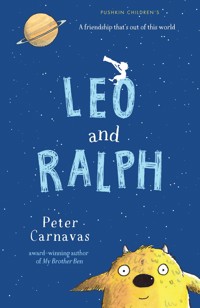

A stellar novel about space, starting over and the best friend you could ever imagine. Ralph sat up. His voice was croaky. 'If a shooting star past right now, what would you wish for?' 'To find another friend like you.' Leo and Ralph have been best friends ever since Ralph flew down from one of Jupiter's moons. But now that Leo's older, his mum and dad think it's time to say goodbye to Ralph. When the family moves to a small town in the country, they hope Leo might finally make a real friend. But someone like Ralph is hard to leave behind...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 175

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

iii

v

For my sister, Jo

vi

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Leo and Ralph lay on a blanket in the backyard, looking up at the night sky. It was dark but not too dark, as the glow from streetlights cast a soft haze across the neighbourhood. Only a few of the brightest stars poked through.

‘Hey, Ralph.’ Leo held a telescope to his eye. There was a crack on the lens. ‘Which planet should we look for?’

His friend rattled a sigh, and his voice had a soft growl when he answered. ‘Flumblebot.’

Leo smiled. Flumblebot was his favourite of all the planets they had invented. Home to a 2group of friendly aliens called Grimbles. They had two heads, smooth pear-shaped bodies and they spoke in backwards sentences.

‘Okay, then.’ Leo focused the cracked lens on a spare patch of the sky. ‘If a Grimble from Flumblebot landed in this yard right now, what would you say?’

Ralph lay still. The reflection of a star twinkled in his eye. ‘I’d say: snacks bring you did?’

Leo dropped the telescope and rolled over, laughing. Ralph always cracked him up like that. They had lain on this blanket, staring at the sky, hundreds of times. Dreamt of planets with funny names, imagined the creatures that lived there and the spaceships they might fly. If Mum didn’t call out to Leo each night, he would probably never go inside. He’d stay out until morning, lost in those faraway worlds that no one else knew. No one – except Ralph.

They gazed up for a bit longer. Then, slowly, the night air cooled and something shifted in Leo. A cold feeling seeped into his feet and 3up through his body, the way a bad memory steps from shadow into light. The feeling came because Leo knew this was the last time he and Ralph would do this. The last time they would share this blanket on the grass, look through the telescope and talk about aliens. Tomorrow the truck would arrive and take all the taped-up boxes from the lounge room. All the furniture and everything from the garage. Then Leo would sit in the back of the car to wherever it was they were going, to start all over again. New town. New school. A new life without his best friend.

He sat up, crosslegged, with his chin on his fists. He couldn’t imagine doing anything without Ralph. Before they met, he was like an asteroid, orbiting the other kids, not knowing what to do. As soon as Ralph arrived, school became less scary, the grown-ups stopped worrying and Leo had the friend of his dreams. He didn’t want to go back to the way things were, especially in a place where he didn’t know anyone. 4

The back door of the house squeaked open. Leo didn’t turn round, but he knew it was Mum.

‘Leo, love. It’s nearly bedtime.’ She waited, and he felt the whole world pause with her, as if that cold feeling had slithered across the grass and found her too. ‘Two more minutes, okay?’

‘Okay, Mum.’

The door clicked shut.

Ralph sat up. His voice was croaky. ‘If a shooting star zoomed past right now, what would you wish for?’

‘Easy,’ said Leo. ‘To stay right here.’

Ralph shook his head. ‘Apart from that.’

‘To take you with me.’

‘Or that.’

Leo looked up at the blurry sky and tried to picture an alien ship floating down. Blinking lights, a soft swooshing sound, the strange shape of it getting bigger. Then the back door squeaked open again. Mum was there, waiting. 5

Leo faced his friend. He was hunched on the blanket, his hair was moon-grey and his wet eyes shone in the dark.

There was only one thing to wish for.

‘To find another friend like you.’

They hugged for a long time. Ralph always gave the best hugs. Then they said goodbye the way they always did: backwards, like the Grimbles from Flumblebot.

‘Tomorrow you see.’

‘Tomorrow you see.’

It wasn’t true. They wouldn’t see each other tomorrow. But they couldn’t bear to say goodbye any other way.

Leo let go of his friend and plodded up to the house. Before he went inside, he threw the telescope in the bin at the bottom of the stairs. He wouldn’t need it anymore.

THE WHITE BALLOON

One day, when Leo was five, he saw a white balloon sweeping through the sky. It was a long way up and it bobbled as it streaked over his house, the way a bike shudders when it’s going too fast. He ran around the yard to keep it in sight, and he wondered who had let it go. It was trailing a long ribbon, so it had probably escaped a birthday party, slipped from the hands of a kid like him. It flew further away, higher and higher, shrinking to a small white dot. As it grew smaller and then disappeared, he stopped thinking about where it had come from. 7Instead, he wondered where it was going and where it would stop. If it kept floating higher, would it ever stop at all? The thought was almost too big to hold.

8Lots of things felt too big because he was smaller than other children his age. His short legs could never keep up when they walked in lines at school, and he took longer than others to climb steps. He otherwise looked like an ordinary boy – pointy chin, freckled nose, a mop of sandy hair – but he never seemed to fit neatly into the jigsaw puzzle of other kids.

While they pushed tractors and spades through the sandpit, he wondered how many grains of sand were stuck to his palm. His Prep teacher had to repeat her questions because his eyes were often fixed on a corner of the room, watching a spider weave its web, or a raindrop wriggle down a window. He imagined faces in tree trunks, contemplated the life of an upturned beetle, and followed the epic journeys of ants 9as they carried their treasure from one end of a path to the other.

His head was filled with questions. Were his footsteps like earthquakes for tiny bugs in the grass? Why was an apple called an apple and cake called cake? What if everyone slept during the day and stayed awake at night?

He sometimes shared his thoughts with other kids, but he spoke too slowly for them to catch on.

‘If … dogs could, er, talk, what would they …’

Why did his ideas come out like that? It was like the words had just woken up and were wandering round, trying to find each other. Mum said there was nothing wrong with taking time. Dad told him not to worry because the world needed to slow down. Either way, the other kids were baffled or bored. They didn’t care for the size of his thoughts or the time it took to share them, and they butted in or walked away before he finished talking. 10

So Leo drifted to the fringes of playgrounds. He kept his ideas to himself, but they didn’t stop growing, and his biggest thoughts came when he saw the white balloon that day. After it had blown over his yard, he thought about it all afternoon. That night, when he climbed into bed, the disappearing dot was still pulsing in his mind. He waited until his parents had put his little sister Peg to bed, then he asked Mum about it. She was a teacher, and he liked the way she explained things.

‘How long will it float for?’

‘Well …’ She pulled the blanket up to his shoulders and flattened it over his chest. ‘It’ll float as long as there’s air inside. A long time if the knot is tight.’

‘Will it float forever?’

‘I think it will come down one day.’

‘Where?’

‘Anywhere. In the branches of a tree. In someone’s swimming pool.’

‘What if the wind blows it higher?’ 11

Mum put a finger to her chin. It was pointy like his, but her hair was dark like cocoa. ‘A flock of geese will pop it if it gets too high.’

‘Huh.’ He almost laughed, but he was still full of wondering. He wanted to know more about the balloon and the sky and how big it all was. ‘Mum.’ His eyes were wide. ‘Where does it end?’

She narrowed one eye. ‘Where does what end?’

‘The sky,’ he said. ‘Where does it end?’

She combed her fingers through his hair and held the back of his head in her hand. ‘It doesn’t end, Leo. It goes on forever.’

‘Forever?’

She reached across him and opened the curtain just enough to see a piece of the starry night. ‘Above the sky is space. It just keeps on going. And we don’t know much more than that.’

He laughed this time. The whole sky – all that endless space – was suddenly inside him, filling his chest until he thought he might burst. It was the most exciting thing he had ever heard.

QUESTIONS

From that day on, Leo looked up. He thought about the colour of the sky and the coming and going of stars. He noticed the changing angle of the sun and when the moon hung around in the daytime. Mum could explain a lot about the sky. Dad helped too. He was freckled like Leo, but he mowed lawns all day, so the sun had turned his arms and legs the colour of golden syrup. In his spare hours, he drew pictures of animals, and in the afternoons, when he cooked dinner or read stories to Peg, he tried to answer Leo’s questions.

‘What’s the sun made of?’ 13

‘Gas, buddy. It’s a big ball of gas.’

‘How does it stay in the air? Will it ever fall down?’

‘I don’t think so. Something to do with gravity.’

The biggest thoughts that Leo had were about deep space, the never-ending expanse of emptiness beyond the blue sky. He couldn’t stop thinking about the wild impossibility of it all. But as his curiosity roamed further into the distant dark, his questions grew larger and the answers grew thin.

‘How many planets are there?’ He sat on the kitchen bench while his dad peeled potatoes in the sink. Peg was at the table, trotting the salt and pepper shakers around like they were best friends.

‘Well, there are eight,’ said Dad. ‘There used to be nine. Pluto’s not a planet anymore.’

‘What happened?’

‘Nothing, really. Someone just realised it wasn’t big enough to be a planet.’ 14

Leo swung his short legs. ‘That’s not fair.’

Dad grabbed another potato. ‘But there are probably more we can’t see. Way out in space. Just because you can’t see something, doesn’t mean it’s not there.’

Leo’s eyes twinkled. He liked that idea. ‘How many more planets do you think there are?’

‘No one knows. Millions, maybe.’

Leo felt the sky filling his chest again. His head swirled and his hands tingled. He wasn’t sure what millions meant but he knew it was big. ‘If there are millions of planets, then there must be other people out there.’

‘Well, not people,’ said Dad. ‘Something else, maybe.’

‘What, then?’

‘Aliens, I guess.’

Leo repeated the word. ‘Aliens.’

Dad put down the potato peeler. For a quiet moment, they both gazed out the kitchen window at the darkening sky. Leo didn’t 15know what his dad was thinking, but his own thoughts shone as bright and clear as the first evening star. Something else was living out there and one day he would meet them. Just because you couldn’t see something, didn’t mean it wasn’t there.

MUM’S WISH

One night, Leo heard Mum and Dad talking in the lounge room. He was in bed, but his door was open a bit. The television threw a hazy blue light on the walls and his parents spoke in quiet voices.

‘Know what he asked me today?’ Mum said. ‘He wanted to know if we’d let an alien stay, if it landed in the backyard.’

‘What did you say?’

‘Sure, if it paid rent and cooked us dinner sometimes.’

They both laughed.17

‘Do you think … I don’t know.’ Mum’s voice turned soft and serious. ‘Do we need to worry?’

‘About what?’

‘All this space stuff.’

‘Lots of people think about space.’

‘But it’s allhe thinks about. And I’m worried he doesn’t try with the other kids anymore.’

Dad let out a long, slow breath. ‘They don’t give him a chance. He tries to talk but, you know, his words …’

There was nothing for a while. Just the low mumble of the television.

‘All his ideas, all his curious questions,’ said Mum. ‘I wish he had someone to share them with. I wish he had a friend.’

The television light flickered onto the walls for a while longer. Then his parents switched it off, went to bed, and Leo lay in the dark. He didn’t sleep for a long time because he didn’t know how to make his mum’s wish come true.

DAD’S IDEA

The next morning, Leo finished his Rice Bubbles and rolled his coloured pencils onto the table. He opened to a fresh page in his scrapbook and started drawing. A round, furry shape with ten googly eyes. A long, green, spiky thing with wheels instead of legs. A fluffy cloud with lots of arms and a big pointy nose.

Dad stood close by, watching him. He smelt like sunscreen and he tucked his dirt-brown mowing shirt into his dirt-brown shorts.

Leo asked questions as he drew. ‘How many yards do you mow?’ 19

Dad laughed. ‘Not enough.’

‘Do you like mowing yards?’

‘Someone’s gotta do it. I’d rather be doing what you’re doing. Drawing pictures.’

Leo swapped a green pencil for a blue. ‘So why don’t you draw pictures?’

Mum stuck her head in from the kitchen. ‘Because if your dad drew pictures all day, we’d be living in a tent.’ She poked out her tongue.

He stopped drawing. ‘Why would we live in a tent?’

‘Don’t worry, bud.’ Dad leant on the back of the chair and looked at the scribbly aliens. ‘Does anyone at school like space stuff?’

Leo shook his head. He held his tongue out of the corner of his mouth as he drew.

Mum appeared, zipping up a lunchbox. ‘Have you asked?’ Then she wrapped her arms around him. ‘You have all those space facts growing in your head. There must be someone at school who’d like to hear them.’

Leo chewed his pencil. 20

‘Why don’t you try today?’ Dad pulled a wide-brimmed hat onto his head. ‘Show someone your pictures. Tell them some things you know.’ He patted Leo on the back. ‘It’d be good to have a friend, buddy.’

Leo dropped his head. He knew what would happen if he tried to talk to the other kids. His words would sleepwalk, and everyone would butt in or walk away. It was easier to look out the window and up at the sky, to imagine a friend falling from space.

MORNING ACTIVITIES

The school day started on the colourful mat. Leo sat on the edge behind the other kids. Some of them tugged at their oversized uniforms, others keeled onto their backs and rolled around, unable to stay still. Leo sat straight, trying to keep his eyes ahead instead of staring at the sky outside the windows. Mrs Lloyd pointed to a weather chart, sang an alphabet song and read a book about a pig who sailed the world. A story about aliens skimming through space would have been better.

In Morning Activities everyone chose to 22work at one of the stations around the room. There was a dress-up corner, a puppet theatre and tubs of building blocks. Leo sat at the construction table, a hexagonal desk with jars of buttons, beads, nuts and bolts, pipecleaners, pom poms and glue. He started with a big styrofoam ball and covered it with shiny beads and stickers. Then he remembered what his parents had said that morning and Mum’s wish from the night before.

A skinny dark-haired girl sat on the other side of the table. He couldn’t remember her name.

‘Hey. Look at my, uh, planet.’

She didn’t look up from the pipecleaner she was trying to cut in half.

‘Did you know there are—’

‘That’s not a planet,’ she snapped, without lifting her head. ‘It’s an ice cream that lost its cone.’

The next day, he went to the dress-up corner. He pulled a long stripy skirt up to his armpits, 23squished his feet into some flippers and clipped a pair of wobbly antennae to his head. Another boy was dressing up beside him. He was only a bit bigger than Leo and his name was Henry. Or Hugo. Probably Henry.

‘Henry,’ said Leo. ‘Do I look like a—’

‘Huh?’ Henry had a beanie pulled down over his face and knocked over one of the dress-up tubs.

‘An alien.’ Leo pointed to his antennae, even though Henry couldn’t see a thing. ‘They, you know, they live in space.’

Henry ripped off his beanie and frowned. ‘I’m James,’ he said, and walked away.

On Friday, Leo sat at the drawing station. He used crayons to draw a round purple alien with a wonky smile and held it up to some other kids. A boy snatched the drawing, studied it, then drew an army tank rolling into the scene, its gun pointed at the alien.

That afternoon, the class gathered on the colourful mat. Leo was tired. He lay back and 24stared at some plastic stars stuck to the ceiling. There was another song and another book, but he just lay there, looking up. Right before home time, Mrs Lloyd announced her Star of the Day. It was the army tank kid.

THE ALBUM

Saturday morning sounds swirled through the house. The vacuum cleaner hummed. The washing machine tumbled and turned. Music swam through the open windows from a neighbour across the street. In the kitchen, Leo stirred a glass of chocolate milk, watching the whirlpool speed up and slow down. At the table behind him, Peg squished playdough into lumpy shapes.

Everyone was busy. That was good. Leo wanted to forget about school and hoped Mum and Dad would too. He joined Peg at the table, 26tore off a chunk of playdough and rolled it into a ball. When it was smooth and round, he added three eyes, a pair of horns and a line of spines across its back. He showed it to Peg.

‘It’s an alien,’ she said.

He nodded. ‘I’ll call this one a … Gronk.’

He put it to the side and made some more. There was a cube-shaped creature with one eye, a lumpy yellow thing covered in pink spots, tiny round critters, long wobbly beasts, and one that looked human, only with two heads and an extra pair of arms.

He stood and admired his creations. Each alien was different, but they all looked friendly. Big smiles, wide eyes – he couldn’t imagine any of them butting in or walking away.

‘Are you going to keep them?’ said Peg. ‘I need more playdough.’

Leo ran into his room and found the polaroid camera he shared with her. He came back to the table, lined his aliens up in a row and took photos of them, one at a time. When the camera 27

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)