7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

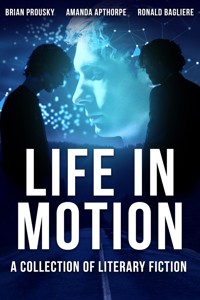

A collection of three novels by Amanda Apthorpe, Brian Prousky & Ronald Bagliere, now available in one volume!

Whispers In The Wiring: After the death of his twin brother, Catholic priest Rupert Brown is burdened with grief. When neuroscientist Athena Nevis invites him to take part in her research on heightened religious experiences, Rupert begins to question his life. Soon, Athena’s and Rupert’s interest begins to extend beyond their professional relationship, bringing them both face to face with their values and spirituality.

Auden Triller (Is A Killer): Simon and Auden Triller are twins whose only similarity is the surname they share. Auden’s life is as sparse as Simon’s is full. Auden realizes that the solitude he’s chosen for himself is less peaceful than insanity-making. When he finally loses his grip on reality, his actions precipitate a tragedy that threatens to sever his fraternal bond, just when he needs Simon the most.

Starting Over: After a devastating loss, Janet Porter’s life in Oregon's Willamette Valley has begun to settle down. When her son Nate returns home from Iraq on a medical discharge, he just wants to be left alone. Desperate for help, Janet confides in Andy McNamara - a war veteran who volunteers at the local V.A. clinic. Soon, it becomes clear that Nate's wounds go far deeper than his torn-up leg. As a tornado touches down in Willamette Valley, they're all thrown into a new world - a world of starting over.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

LIFE IN MOTION

A COLLECTION OF LITERARY FICTION

AMANDA APTHORPE

BRIAN PROUSKY

RONALD BAGLIERE

CONTENTS

Whispers in the Wiring

Amanda Apthorpe

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Acknowledgments

You may also like

About the Author

Auden Triller

Brian Prousky

Auden

I. Simon

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

II. Auden

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Afterword

About the Author

Starting Over

Ronald Bagliere

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2023 Amanda Apthorpe, Brian Prousky, Ronald Bagliere

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2023 by Next Chapter

Published 2023 by Next Chapter

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

WHISPERS IN THE WIRING

AMANDA APTHORPE

For Alison

1

Rupert reached into the top of the wardrobe. His hands groped among the many books and the few items of clothing. When he felt the rough texture of the cloth, he knew he’d found his mark. His fingers traced the hard edges of its contents. Lifting it down he placed it on the bed, smoothing the quilt around it. He sat carefully on the bed’s edge and loosened the cloth to reveal a solid black plastic box and sat back from it, staring at it in quiet disbelief, the fingers of his left hand twisting the plain gold ring on his right. Rupert picked the box up again and held it to him, unable to comprehend that the brother he loved so much was now reduced to an area smaller than a lunch box. He had expected something more fitting for his brother’s remains, but the weak voice of practicality reminded him that he lived in an age of disposability. The absurdity of it struck him and might have brought a smile to his lips were it not for a weight that was dragging at his heart. He wished that he could unburden that weight. He felt it physically, a heavy sensation in his chest that drew strength from his arms and legs and caused his breath to come in sharp gasps and to leave in long, fractured sighs.

He turned the box around until the plastic stopper was facing him — the stone across his brother’s tomb. His thoughts drifted in a black and grey kaleidoscope and came to rest on the last conversation he’d had with Ross. He remembered the pain in his brother’s voice, unsuccessfully disguised by too much alcohol, and the chilling sound of his despondency when he sighed and said that he didn’t think he was of use to anyone anymore.

“But you mean something to me! And to Neti!” Rupert had replied with urgency but also a small amount of irritation. He had listened as he always had. He had told Ross what he meant to him. He just wished that he’d never put down the phone; that he’d kept talking to him. If only he’d known that they would never speak again.

But how could he have known? How many times had those conversations taken place? That instance, like so many others that had occurred all through their lives, caused Rupert to wonder where personality originated. It couldn’t lie in the genes as some scientists claimed — Ross was his identical twin. If it were in the genes then Rupert too, with the help of a whisky bottle, would have tried to obliterate the pain of living and rammed his car into a tree. Or, conversely, Ross also would have chosen the safety of religious life and lost himself in the rituals and self-admonishments in an attempt to suppress the ego.

Rupert picked and prized at the plastic stopper that popped open to reveal the contents inside. No angels at the tomb, he thought ruefully. He held the box up closer to his eyes and could just make out the greyness of the ash against the black interior. His hand and the box dropped to his lap.

“Oh … Ross …”

The weight was dragging at his heart and constricting his throat, preventing him from breathing. The feeling was made worse by his attempt to stifle the sobs that were straining to be released. His mind raced through an assortment of images of his life with his twin — childhood scenes confused with adult conversations, the face of his brother one minute laughing, the next sobbing into Rupert’s chest.

Gathering himself together, he sat upright. He lifted the box again and, tilting it towards him, dipped two fingers tentatively through the opening. The ash felt cool and some adhered easily to the sweat on his fingertips. He withdrew them and stared at them blankly, his mind having shifted to that empty space known to those in shock. Closing his eyes, he lowered his head to his chest and brought the fingers to his head. Lightly touching the space between his eyebrows, he began to apply the ashen traces of his brother to his forehead in a barely discernible sign of the cross.

Remember Man That Thou Art Dust.

2

Had only two weeks passed since Marjorie would find Rupert in the staff room spending time between lectures in easy chatter with colleagues? Now, after his brother’s death, he more often slipped quietly into his office and, she imagined, shut the door behind him in relief.

Marjorie knew this was where to find him. She knocked and entered his study at his invitation. He was sitting marking papers by the window. In the ten years that Rupert had inhabited this office, very little had changed. He was an orderly man, sometimes to a fault. As a teacher though, he was renowned for his knowledge and his patience. Marjorie fancied that she could tell more about her staff on visiting their offices than she could by visiting their homes, which for some, like Rupert, was just a room in the College. For most who taught theology here, teaching was their life, and their offices reflected that life. Sometimes they were sad places, especially for the residents, no photographs of family and friends, no impractical presents from children, no sign of other interests or hobbies. However, this was not true of Rupert, and in some ways, this was his contradiction. His office was sparse, but there were photographs, small ones in wooden frames of his mother, his brother Ross, and of his niece, Neti. These did not sit publicly upon his desk, but on the bookshelf across the room. Each photograph, she noted, was angled to take in the others while also facing him at his desk.

He looked up and smiled at her; she was struck by the gauntness of his face — not that anyone else seemed to have noticed, or if they had, no one had commented. Perhaps it was the light diffused by the old diamond-paned windows behind him that made his skin look sallow and his eyes appear haunted. She wished he would turn on the light so that she could appraise him more carefully.

“Hello,” he said.

She stood inside the doorway. There was something about this time of the afternoon that made her feel melancholy, as if life itself might decide whether to continue or not. In the clearer light of the earlier day, everything seemed to have more reality. This College, its yellow sandstone buildings and carefully maintained gardens, successfully gave the impression of all that is solid and established, of order and substance. But in this light, this twilight, the sandstone wall that Marjorie could now see through Rupert’s window was colourless. The students milling at its base looked tired and less self-assured than they had only a few hours earlier. She looked at Rupert, who was making a final correction to the paper in front of him, and, for a moment, Marjorie was struck with a sense of futility, as if all that took place within the College walls — the supposed sense of purpose and commitment — amounted to nothing.

I must be tired, she thought.

Rupert rose from his seat, gesturing towards the two chairs on the far side of the room.

He crossed the room and waited for her to sit before seating himself opposite her.

Marjorie placed the envelope she was carrying on the coffee table between them. She looked into his eyes.

They’re haunted, she thought.

His normally long, thin face was thinner still and pale, almost grey. Marjorie feared for him. Rupert was forty-two and, although he was lean and conservative in his habits, he was of an age at which two of their colleagues had suffered sudden heart-attacks; one of them fatally.

“How are you? … We miss you in the staff room.”

“I’m all right.”

She leaned towards him, her voice dropping a tone.

“How did it go at the weekend?”

There was a pause before he answered.

“Well, we scattered his ashes where he wanted.”

His voice was practical and steady, but she noticed the colour rise in his face.

“That’s about it really … It’s all over now.”

“What about Neti?”

He cocked an eyebrow.

“She made an inappropriate comment at an important moment.”

Marjorie noticed the flicker of irritation on Rupert’s face.

“It’s probably the only way she knew how to cope with it.”

“Yes.”

“How are the two of you getting along?”

“Like any fifteen-year-old and a stuffy forty-year-old might!”

“Your words or hers?” Marjorie said smiling.

A small smile forced itself onto Rupert’s lips.

“Mine. Neti would never use a tame word like ‘stuffy’.”

“When are you moving?”

“Neti’s away with her friend’s family at the moment. I’ll move into the house tonight. She’ll be home tomorrow.”

Marjorie took an intake of air and let it out slowly as she spoke, “It’s not going to be easy … You’ve lived here for a long time on your own.”

“I know, but I lived in the religious community for twelve years,” he offered with hope. He looked down at his hands. “I’m going to need your advice on raising a child — an adolescent, I mean.”

Her eyes followed his to the gold band on his finger.

“Ross’s ring?”

He didn’t look up.

She spoke to his bent head, “Will everything be all right Ru, financially, I mean?”

Thoughtfully, Rupert raised his head.

“Despite Ross’s limitations as a father, he has left a considerable legacy for Neti. It makes me wonder if he knew …”

The air felt heavy between them. She reached for the envelope on the table.

“I thought you might be interested in this.”

She slid the letter from its jacket and held it out to him.

He took it from her. “What is it?”

“A letter … a request from a post-graduate student — PhD, I think, in neuroscience. She is wanting to interview anyone here who has had ‘an intense religious experience’ to use her words. I thought you might—”

“Oh no … no … I don’t think so,” he said handing the letter back to her.

“Just think about it.”

She slipped the letter back into the envelope and placed it on the table as she rose to leave.

He rose with her.

Marjorie paused at the door and placed her hand on Rupert’s arm in a gesture that revealed their long friendship.

“It might be what you need …” she said, “to talk about it again.”

He saw her expression and smiled. “I’ll think about it.”

* * *

Rupert closed the door behind her and turned back to his desk, avoiding the envelope still sitting on the table. The marking of papers seemed to be an endless task, made more so by the fact that he had to reread sections of students’ work more often than usual. He found it difficult to focus on the content, and when he did, it seemed to be trivial and irrelevant. He knew that this was unfair, that each student deserved his full attention and to be taken seriously. Since Ross’ death and funeral, however, it was increasingly difficult to assign significance to anything. When Ross was alive, he hadn’t thought that his brother gave his life its motivation, but it now felt that there was little reason to go on without him, except for his responsibility to Neti. He didn’t want to end his life, but he felt that if it did end, it wouldn’t matter. If Ross could go … so could he. He remembered that he had even felt some envy as the coffin was lowered to the flames. He didn’t want to be the one left behind and felt that the greatest void existed in living, not in dying.

He thought about Neti and how she felt. She had given nothing away emotionally in the last two weeks. At her father’s funeral, she sat impassively, studying her nails, although her chin was tucked close to her chest as if to contain anything that might leak from her heart and mind. He felt overwhelmed by the need to protect her but was daunted by the responsibility he was about to take on.

* * *

At his brother’s home, that was now to be his own, Rupert poked at the charred logs he’d placed too early on the fire, hoping that something would take. He wanted the house to be warm and cheerful for Neti’s arrival home, but he seemed to be thwarted in his attempts. He wondered whether he should put on some music, or perhaps the television, to create an atmosphere that might alleviate the inevitable silences between them. He decided on the television, which was now creating an uncomfortably chirpy background and made him feel like a court jester waiting in the wings to perform to a temperamental monarch.

He didn’t know what Neti liked to eat, except for the various types of junk food he’d seen her consume with gusto on outings with Ross. A stock-take of the pantry revealed his brother’s absence sharply. Rupert pictured him selecting each item from the supermarket shelf. In the end, the pantry’s contents gave him no assistance; it seemed that father and daughter had lived on three-minute noodles and sauces found in jars with nonsensical names. He resorted to ordering Chinese take-away; he’d found a phone number, along with those of many other home-delivery restaurants under colourful magnets on the refrigerator. Even the simple task of ordering for them both caused him some anxiety. He was becoming acutely aware of his worldly incompetence.

Stepping into his brother’s home had been difficult. He had not been here since the day Ross had died in the accident. Neti had been away on school camp and was due back that day; he suspected that her absence for a week unleashed Ross’s fatal drinking spell. Rupert had waited at the school for the buses to return from camp. She was not surprised to see her uncle instead of her father — Rupert occasionally had to fill in when Ross was away on business trips. He remembered that she was flushed with excitement about the trip and full of stories about friendships made and lost; he also remembered, too vividly, her face when he told her about her father — how she turned a ghostly white and sat back from him, suspicious of his motives in telling her something like that. She had kept that distance ever since.

On this day, he would attempt to recreate a home for her. Concerned parents of Neti’s friend had asked to take her in immediately until living arrangements were sorted out and so little had been disturbed at the house. When Rupert came in, the door to Ross’s bedroom was closed. Inside, the room was tidy and the bed made. Ross’s slippers were lying just inside the door and were askew, as if someone had thrown them in quickly and shut the door. Rupert had stared at them, too easily picturing them on his brother’s feet. He slipped off his own shoes and stepped into them. His breath caught in his throat, and he quickly took them off again and shut the door behind him.

One hopeful flame burst from the embers in search of loose, dry bark. Rupert stood, flexing his body to ease the strain on his lower back. He turned around and scanned the lounge room, trying to imagine he was looking at it through Neti’s eyes. Lamps on, television on, fire almost glowing, flowers in the vase on the coffee table. Is this what it would have looked like when she came home from school to her father? Too often she would have found Ross in a state of depression, with alcohol on his breath when she kissed him hello. No doubt Ross had tried to hide it from her. He was a good and loving father, but the eyes and ears of a fifteen-year-old are acutely tuned to the fraudulence of adults.

Leaving the residential college at the university where he had lived for ten years had been much harder than Rupert had thought. When he’d arrived, he’d been an eager thirty-two. He was more than ready, after twelve years in the seminary, to share his knowledge and his faith with his students — and he was satisfied with his calling. Occasionally over the following years, he’d fantasized about living in what some people called the ‘real world’ — marriage, children, mortgage; he wondered if he was missing out on something. Very often though, these were fleeting fantasies. His role as priest, and more particularly as confessor, exposed him more than most to the darkness of the human heart and, although he felt a genuine compassion, he could not empathize. Nor did he want to. Instead, he found himself wanting to distance himself further from the everyday human experience. That marriage and family life were not for him was reinforced by Ross’s bitterly unhappy marriage and separation, but it had its roots much earlier in his own unhappy childhood.

When he’d closed the door to his room for the last time the previous day, he knew he was also closing a significant chapter of his life. To the outside world, his life would not appear to be much different; he would continue lecturing and carrying out his duties as the College chaplain. But his internal life was undergoing changes, the nature of which he could not determine, nor did he want to — he sensed that danger might be lurking there.

Rupert turned back to the fire, his eyes flicking along an assortment of photographs on the mantelpiece. From the corner of his eye, one of them caused him to start. It was a picture of Neti and Ross, but he had thought for a moment it was himself. Although they were identical twins, neither could really understand the difficulty others, even their own parents, occasionally had in telling them apart. Looking now at this photo, he was taken aback. What would Neti think when she walked into her home and saw him? A surge of panic went through him. She had always known him, seen father and uncle together, and she had faced him during the terrible weeks of Ross’s death, but tonight was different. He was to be her guardian, living with her as her father had, and this was the beginning of that life together.

He heard a car door close in the driveway and the car leave. What was he to do? Open the door to greet her wearing Ross’s face? Should he be doing something? Maybe with his back to her, humming nonchalantly, so that when she said hello, he would turn his head slowly, allowing her to adjust to the sight of him? Before he could decide, she was opening the front door. He bent down to the fire and stabbed at it repeatedly with the poker and began to whistle a cheerful tune. He heard the door close loudly behind her, announcing her arrival in a clear statement. His stomach lurched and the set of his jaw would no longer allow him to whistle.

Neti seemed to be unaware of him standing by the fire when she walked through the lounge-room from the front door. Although she must have known he would be there, she didn’t seem to be looking for him. Instead, she headed resolutely to the kitchen, her gaze fixed ahead, the stiff movements of her body betraying her tension and giving her a slightly uncoordinated gait.

“Hello,” he said from behind her. He noticed that her hair was now a combination of bright red and brown streaks that had been cut into short, aggressive spikes.

“Welcome home.”

She froze mid-stride and seemed to be debating whether to keep going. She turned her head slowly, the rest of her body still facing its preferred direction.

“Hello.”

She said it without raising her eyes to him. The first of many silences fell between them, filled only by the drone of the television. He was glad now that he’d put it on.

Rupert thanked Polly’s father who was waiting at the door and noted his look of sympathetic concern as he handed Rupert Neti’s bags of clothing.

“If there’s any way that I can help …”

Rupert thanked him, sincerely wishing that he could.

When he returned to the lounge room, Neti was in the kitchen.

“You haven’t eaten, have you?” he asked too cheerfully. He continued quickly, trying to stifle the silence that answered him. “I’ve bought some Chinese food.”

“I’m not hungry.” Her eyes lifted to his. There it is, he thought, the look of panic and pain. But it was fleeting and was instantly replaced with a look of contempt.

He had imagined that, on her return home, she would run to him as she had as a little girl. He had pictured her crying into his chest as he consoled her. Instead, she faced him coldly, half a room separating them.

“I’m going to bed.”

She turned on her heels, steered away from the kitchen and headed up the passage to her bedroom, slamming the door behind her.

* * *

Almost as soon as it left her hand, Neti regretted the force she had applied to the door. She threw her bag into the corner of the room and fell face down on the bed, burying her head into the pillow. She flipped onto her back and lay staring at the ceiling looking for the old familiar patterns in the cornices; the tiny imperfections that were like secret messages from a master craftsman of an older time. Normally she found comfort in the shapes and chips that took on the appearance of animals and faces of imaginary people who had been her childhood friends, but tonight she couldn’t empty her mind enough to allow them to manifest.

She rolled onto her side to look at the streetlights through the window, but nothing engaged her there. She rolled to her other side and let her eyes wander over the bits and pieces on her bedside table. She studied her collection of small china horses; rock pieces she had collected with her father on Sunday drives, each piece clearly defined by the light of the lamp that her uncle had put on earlier to greet her home. Standing out sharply from these was a small red bird made of cloth, stitched with gold and coloured thread, a Luck Bird her mother had sent to her many years ago after one of her many trips to Thailand. That’s what her father had said anyway, with a note of sarcasm in his voice. She must have sent it not long after she left them, but Neti had not received anything more in ten years. She often wondered if her father had intercepted the gifts and had, a couple of times, looked in his room for unopened parcels and letters addressed to her. She had never found anything but was certain that they must exist. A mother would not just forget about her child — she was sure of that.

Neti propped herself up and took the bird from the table. She ran a thumb gently over its surface, circling its large woven eyes over and over. She could not remember much about her mother, but her father had given her a few photographs of happier times when they were a family. Still holding the bird, she opened the drawer of the table and took out a black book with an inset lock. She rummaged through the graffitied pencil case on the floor and produced a tiny key. From the back of her diary, she took out a photograph. It was of herself as a newborn resting in the crook of her mother’s arm, her father sitting beside them. She dwelled momentarily on his image before placing her thumb over his face and, concentrating on that of the woman staring back at her, looked for similarities in her mother’s face to her own. She decided that, yes, she could recognise some common traits; here, in the downturn of the eyes, there, in the soft cleft of the chin.

What had happened between her parents? She had asked her father, but he became subdued and would only say that her mother found it hard to adjust. Adjust to what? Neti felt that he had waited for his wife to return, and so she too lived with that thought. She placed the bird on top of the photograph, its body obscuring her father’s face. Her mother would come home, she thought. She must come home now.

* * *

Still standing with his back to the smoking embers, Rupert winced as the door slammed. There was a moment of déjà vu — of walls shuddering as doors slammed and of malignant silences that grew between his feuding parents.

A long-buried but familiar knot was forming in his stomach. He automatically assumed the deep-breathing method he had devised in his childhood as a coping strategy.

What was he to do about Neti? His uncertainty rooted him to the hearth. Rupert forced his feet to cross the room to the passage and to her door. He raised one hand, knuckles bent for the knock, but drew it away again before making contact. He leaned forward, resting his forehead on the cool wood while he debated his next move. He thought he could hear her sob in an otherwise silent room. He straightened himself and raised his hand again only to see the lamplight go out from under the door.

He turned back to the lounge room, switched off the television, turned the armchair to the face the fire and sank into it.

For a long time, Rupert sat staring ahead, his mind in such a confusion of thoughts that, if asked, he would have said that he had no thoughts at all. He hadn’t slept well for the week leading up to this day and after a few hours fell into a light sleep. His body twitched as his mind sank through the levels of sleep. At its deepest point, his breath came evenly but his eyes darted behind his closed lids.

Ross is here sitting beside him, a glass of whisky in one hand, cigarette in the other. Rupert is happy to see him but is not surprised. They have often sat here together. There is one difference this time — Ross is dead. His presence, though, is confirmation that life after death exists and Rupert is relieved.

“What is it like?” he asks with anticipation, only vaguely surprised that Ross is still drinking.

“It’s all right … Nothing in particular.”

And there is that all too familiar desolation in Ross’s voice. He swills his glass and takes a sip, the clink of the ice echoing through Rupert’s growing emptiness.

His misery, heightened by the chill of the room, woke him. He opened his eyes and stared blankly ahead while his brain tried to reconcile the objects in his brother’s home with the expected sight of his old bedroom. He felt drugged from a sleep that had brought him no relief. He placed the screen in front of the fire, switched off the lamp and retired to the small guest’s room at the rear of the house.

3

The sound of the telephone ringing jarred the silence of the office and caused Rupert’s pulse to quicken. He had become suspicious of the motives of the telephone and the sound of a knock on the door — they could only bring bad news. He wondered if he would always be like this. What had once been innocuous enough sounds seemed now to be loaded with ill-meaning.

Reluctantly, he picked up the receiver, “Hello.”

“Hello.” The woman’s voice at the other end of the telephone sounded cheery, and not the bearer of bad news. He relaxed a little.

“This is Rupert Brown.”

The caller introduced herself as Athena Nevis.

There was a pause that suggested to Rupert that he should know who she was. She must have heard his hesitation as she continued quickly.

“I’m researching my PhD at this university, and you volunteered to be a subject?”

‘Volunteered’ sounded more energetic than Rupert’s memory of his response. ‘Coerced’, by Marjorie, would have been the truth.

He had not expected this to be so soon. He was uncomfortable with the whole idea of discussing an event in his life he felt had little significance now. However, he knew from his own experience how difficult doctoral research could be and how necessary it was to legitimize theories.

Rupert invited her to his office the following Tuesday, and they exchanged pleasant farewells. He wrote the appointment into his diary. Athena Nevis sounded older than most of the PhD students he had supervised. Her name, however, suggested that she was from a generation younger than his own.

He wondered what use his own experience could be to her. From what he understood, she was looking for a biochemical factor in experiences of heightened perception, such as in moments of spiritual revelation. He had had one of these many years before. It had been an immensely significant event to him once — the catalyst for his conversion to Catholicism and taking religious vows. Now, he felt anxious at the thought of it, even embarrassed.

He busied himself, shuffling papers at his desk trying to forget about it. He went to the window and looked across to the oval where an end-of-season cricket match was being played in the early autumn light. He needed a distraction, he thought, and left the office to join the spectators, though he sat apart from them. The sun warmed his back and made him drowsy. Through heavy eyelids he watched the players go about their game. The woody sound of bat on ball and the calls of the players lulled him into sleep. He leaned back on the grass and closed his eyes. He slept more peacefully than he had in a while.

* * *

Marjorie saw him from her office. She had caught sight of him as he wandered down to the oval. She watched him now as he sank slowly back into the grass and thought she could imagine him groaning as he did so.

There had been a complaint from a student. Normally, this would not concern her unduly. Her position as Dean of the Faculty meant that she often had to deal with clashes of personalities between students and staff members, although never before concerning Rupert. But this complaint was more disturbing. Rupert, according to the student, made statements during his lectures that were counter to Christian doctrine. Sometimes, a particularly conservative student might find some of the more liberal views of scholars difficult to bear. However, Rupert was calling into question the Resurrection — not in terms of the interpretation of that fundamental event, but he had said that he doubted that it could have happened at all. Though Jesus of Nazareth was a great man, he had said, his life would have ended with his crucifixion, and it was quite likely that the disciples were deluded in their grief. The problem was not so much that Rupert thought this, as Marjorie too had wondered at times about the reality of the Resurrection. It was that he had voiced it in his teaching.

Marjorie left her office to join him on the grass. She sat quietly beside her friend, watching the steady rise and fall of his breath, a measure of the depth of his sleep. She studied Rupert’s face. It was a face that she trusted and one that she loved. They had come to this University at the same time, both in their early thirties, full of enthusiasm and secure in their faith. They had each lived in the same college for years, until her marriage to John. They had shared their thoughts, argued out their different approaches to Christianity — he from the Catholic Church and she from the Uniting Church. She knew about his conversion from the Anglican tradition, and she knew about the profound experience that had triggered it. Rupert had told her one evening as they walked back to the College after dinner. She remembered how deeply the experience that had occurred many years before had affected him. She had always been moved by the intensity of Rupert’s faith, the complete and utter commitment to his religious life, and he had been influential in her own decision to become an ordained Minister.

And now … here he was — a tired body and a withering soul. She sniffed.

Rupert opened his eyes slowly at first and then wider in surprise.

“Are you getting a cold?” he said tenderly.

“Must be,” she said, rummaging through her pocket for a handkerchief. She held it tightly to her nose.

“Ru …”

“Yes.” He sat up on his elbows.

“There’s been a complaint Ru, from one of your third-year students.”

“Oh, the Resurrection?” He looked away from her towards the match that was still being played.

She told him what the student had said, addressing his profile. Finally, he turned to face her.

“What do you want me to do?” he said without emotion.

“Are you admitting that you did say it?”

Although she suspected that the student’s story was true, Marjorie was hoping that Rupert would deny it strongly.

“I probably did.”

Marjorie felt a wave of exasperation.

“Ru … Why? You know you can’t … You have a responsibility.” She was agitated, but more out of concern for Rupert than for the actual incident. She could probably smooth over that one.

Rupert placed his hand over hers.

“I’m sorry Marjorie. You’re right of course. I don’t know what made me say it.”

“I’m worried about you Ru. You’re not yourself. It’s understandable under the circumstances, but …”

“It won’t happen again. I’ll be careful in what I say.”

Although Marjorie might have been relieved with this response, she wasn’t.

“But it won’t be what you believe, will it?”

He looked away from her again, still holding her hand.

“I don’t know.”

Marjorie let out a sigh of resignation at what she should do for him. She slipped her hand out from under his.

“I want you to take some of your leave, Ru.”

He looked at her, perplexed.

Hardly bearing to look at him she continued quickly, “I think you need it. You need to settle into the house and to allow time for the adjustments that both you and Neti need to make.”

“How long?” Rupert said, with some resignation.

“Four weeks. That will cover the coming school holidays anyway. Perhaps you and Neti could go away?”

Despite the strain showing in Rupert’s eyes, there was a glint of humour in them at Marjorie’s last remark.

“That would be fun,” he said.

With a smile, Marjorie reached for her friend’s hand and clasped it tightly in hers.

“Settled?”

“Settled,” he said.

* * *

Subject 1

Name: (Dr) Rupert Brown (SJ)

Age: 42

Sex: Male

Occupation: University Lecturer in Theology

Medical History: Sinusitis, occasional migraine, no chronic illness; no history of mental illness.

Family: to be provided in person

Family Medical History: to be provided in person

Please outline below the nature of your experience of heightened perception: to be provided in person

Athena held the file in her hand as she ascended the staircase to Rupert Brown’s office. He had provided little information that she could use, but he had bothered to return the form. She had wondered if he was going to be prickly to interview, but their brief telephone conversation had been pleasant enough and he sounded quite accommodating.

She scanned the closed doors in the corridor for his name and found it on one that stood slightly open. She knocked and the door opened.

Athena held out her hand to the tall, lean man who extended his in greeting.

“Hello … I hope I’m not too early?”

She was carrying a red coat and he offered to take it from her to hang on the rack inside the door.

Saying little else but a warm hello, Rupert directed Athena to the chairs.

“Thank you for responding to my letter,” she said as she sat down.

“I thought it was important that we meet in person first,” he said.

Athena thought of the response he had written on the form and nodded in agreement.

She sat at the edge of her seat. The man sitting opposite her intimidated her and she was not sure why. She wondered if it was because he was a priest. Although he had not stated this on the form he had returned, she was aware of the significance of ‘SJ’ included at the end of his name. Only now as they sat facing each other did she dare to take him in. Yes, he looks forty-two she thought — pallid complexion, sandy hair carefully combed, a long nose which made his eyes look beadier than they might have against a smaller one. There was a softness to those eyes though; there was a heaviness around them made him appear tired.

As much as she was able to, Athena took in the office around her. It seemed an appropriate one for a theologian, although slightly cliched; wood-panelled walls, bookshelves filled, she assumed, with heavily weighted words, diamond-paned windows that let in a mellow light and a large oak desk. And yet, it was a simple office too and surprisingly void of religious symbols, except for a small cross on the wall behind him.

“Well,” he said smiling, bringing his hands together in a prayer-like position.

She had to contain a smile when she saw that but began to relax.

“Can I ask why you responded to my letter?”

Rupert shifted in his seat.

“I’m not sure, but I was persuaded by my boss.”

His voice was gently articulate with a timbre that was soothing yet commanding. It would be easy to listen to his lectures, Athena decided. She had wondered about Rupert’s ‘boss’ as he described her and had been surprised that the dean of Theology was a woman.

Rupert answered her query.

“The College is ecumenical and it’s not that unusual these days for women to hold such positions … except in the Catholic Church of course. Tell me about your field.”

“Well, it’s neuroscience, as you know. What can I tell you?”

“Everything probably. I know very little about it. How did you get into it?”

Already becoming lulled by that voice, Athena reassessed it and decided that his was the voice of a priest, someone to whom it might be easy to confess. She considered her work in answer to his question.

“I sort of fell into it. No … Fell in love with it. I did my Honours degree in biochemistry and somewhere along the way I became intrigued with the idea that our chemical composition might be underestimated … that our bodies are at the mercy, to a certain degree, of our internal chemical soup.”

He seemed puzzled, so she continued.

“Thoughts, emotions … the works!”

Rupert was silent for a moment while he considered what she was saying.

“So … religious experience, do you mean?”

Buoyed by the opportunity to talk about her work, Athena answered quickly, “A result of particular combinations of neurotransmitters flowing across synaptic junctions, exciting the next neuron.”

“Like an epileptic fit.” he said, but it sounded more a statement than a question.

Athena could feel herself blushing and wished that she’d spoken less hastily.

“Well … look I don’t know enough yet. That’s why I’m researching.”

“How many have responded?”

“You’re the first.”

They both smiled. She continued.

“But there has been some work done overseas.”

“And what do you think might trigger one of these fits? Too many Brussel sprouts?” he said with a laugh.

Athena could feel herself growing redder.

“I didn’t call it a fit … And I don’t know, that’s why I’m researching. To find the trigger”.

“A pity you don’t have access to the brains of some of the saints. You’d find some hefty cocktails in those neurons.”

He was smiling, but Athena could not determine if he was making a fool of her. She paused before replying.

“From what I’ve read, some of their experiences seem to have been symptomatic of manic conditions.”

“Yes,” he said, “I think that’s probably right. Our mental demons manifest in strange disguises — addictions, suicide, crime … religious experience.”

“I didn’t mean …”

She saw him look away; noticed the slow blink of the eyes. There was a sense that he was implying something, about himself and his own experience. She answered, more gently now.

“I don’t know what it is or why.”

“But you think the experiences are not transcendent,” he said, looking at her directly.

Aware that there was more to this question than he was revealing but uncertain what answer he was looking for, Athena could only answer honestly.

“I believe that there is a physiological explanation.”

“I’m sure you’re right.”

There was no hesitation in his reply, and, for some reason, she felt disappointed by his response.

“You haven’t always thought that have you?”

“No.” Rupert hesitated before continuing, “After all, I gave up my life because of it.”

“That’s an interesting way to put it,” she said smiling, but the expression on his face told her a lot more.

Athena studied the man before her who, despite his attempts to hide it, appeared to be under some emotional stress. He twisted the ring on his right hand distractedly and occasionally raised his hand to his temple, pressing deeply as if hoping to obliterate his thoughts.

“Are you alright?” She was surprised by her own directness.

He looked up quickly.

“I’m sorry. I’ve had a recent death in my family.”

Athena gasped. When Rupert revealed that he had lost his twin brother, she was stunned. She thought of the form he had returned to her and realised why he had been reluctant to complete it.

He smiled apologetically and changed the tone of the conversation, sitting even straighter in his seat.

“You’re doing your research at this university?”

Athena noticed his attempt to lighten the situation, but she felt uncomfortable talking about herself now and offered to make another time.

He seemed to be considering her offer, which she thought — she hoped — he would accept.

“Perhaps …” He hesitated. “No, it might be best to do it now. I’ll be taking some leave after this week.”

She searched his face. “If you’re sure that you’re up to it, I would be most grateful.”

Rupert smiled. He scanned the office while making his decision.

“I’m up to it,” he said still smiling. “But do you mind if we move location? I think I need to get out of here.”

“Certainly,” she said, “Where would you like to go?”

“A walk?”

He was already standing, waiting for her.

“That sounds good,” she said getting up and taking her coat from him.

Once outside the office, she turned to him and was again aware of his height. In relative silence they walked down the two flights of stairs. At the building’s entrance they were jostled by students, three abreast, entering for an afternoon lecture.

“Right or left?” Athena asked as shy strangers do when they can never assume to know the other’s mind nor dare to choose for them.

“Left.”

* * *

Rupert was embarrassed about his earlier display and that he had made Athena feel uncomfortable. It often seemed to be the way of late that he was taken unawares by a rising of emotion when he least expected or wanted it. He took her in out of the corner of his eye as they walked, noticing that when the sunlight caught her hair it was a combination of colours including red, a shade deeper than her coat. He had noticed a moment earlier, that same shade in the tips of her eyelashes.

They headed through the grounds of the university towards the river.

“Shall we begin?” Athena had stopped walking.

He paused and ran a hand through his hair, pondering the best way to begin.

“I think I probably need to tell you about my family circumstances at the time … to put it into context.”

“Does it have a context?” she said, a red-tinged eyebrow cocked in mock sarcasm.

“I think you’ll see that it does,” he answered her seriously, “which is why you might be disappointed, no, not disappointed, that’s probably not the right word … vindicated in your beliefs? Oh, I don’t know.”

“Let me be the judge of that.”

He took a deep breath, and they resumed walking.

“Right … Anyway, our family life … Ross, my twin, and mine … was not a happy one. Our parents, well, there was a lot of bitterness there. They argued quite a bit of the time. Loud arguing.”

“Do you mean violence?” Athena asked tentatively.

“No, not so much actual violence. More the threat of it if you know what I mean? That’s almost as bad, I think. That feeling that it’s going to happen at any minute.”

She nodded.

“Well, that went on for many years. Our father was a very domineering man. Our mother … I suppose life would have been quieter if she didn’t retaliate, but that’s not right, is it? That one person should try to dominate like that. She was right to defend herself. She was a proud woman, a good mother and a good wife, if he let her be the woman she wanted to be. Not what he wanted her to be.”

“She didn’t leave him?”

“Oh no. She would never have broken up the family for the sake of her own freedom.”

It pained him to think of what his mother had had to bear. She had been an intelligent woman; she had studied agricultural science and had had a promising future before marrying his father. Rupert knew her frustration. He remembered the rare occasions when he had been alone with his mother, on days home sick from school. She would make him tomato sandwiches, cut in quarters, and sit on his bed to talk. Before long she would be reminiscing about her youth, or she would go through his rock collection, explaining how each of the pieces were formed. Her lovely face would be sad and wistful, and he would touch her hand to reassure her, “It’s okay, Mum.”

“And your father?”

Rupert could feel a little twist of his stomach at the mention of his father.

“He was a Minister in the Anglican Church.”

“Anglican Church! But … I don’t understand.”

“I’ll get to that,” he promised. “He just couldn’t understand that his wife was unfulfilled. It was the times I suppose, but it was very hard on our mother. She developed depression, and she drank. My father, intolerant at the best of times, showed less compassion for his wife than his parishioners. They argued more and more.”

Athena looked down at the ground as she spoke, aware of this personal revelation.

“That must have been very hard for you and Ross.”

Rupert nodded and remembered how he and Ross had pleaded with their mother to stop drinking as the arguing between their parents became more regular. Rupert realized now that she had probably been drinking for years but had hidden it from them. Her increasing frustration and sense of worthlessness in her husband’s eyes only aggravated the problem, to the point that she could no longer conceal it.

“How old were you both then?” Athena said.

“I’d say from about ten onwards. I’m not really sure.”

“How did you feel?”

Rupert noticed how gently she asked him questions.

“We hated it. But at least we had each other. Fortunately, we were the only children. I think … I know that it affected Ross very deeply, for the rest of his life in fact.”

“You were twins you said.”

“Yes. Identical.”

“Identical! That’s interesting.”

Athena stopped walking. Rupert stopped too.

“Why is that?” he said.

She seemed to be deep in thought and spoke slowly, “It means of course that you are … were, genetically identical. The links between our genetic make-up and our emotions is not established but …” She looked up at him apologetically. “It’s just that this is my area of interest.”

They continued walking. There was less traffic now on the path and it was much quieter.

“And I think this brings us to the point of our meeting,” Rupert said as way of getting started.

“Really?” She stopped to face him, confused as to what the connection could be. “Tell me.”

Her eyes are green, Rupert thought. He’d been certain that they were brown.They walked on, more slowly than before.

Rupert used the rhythm of the stroll to launch himself into this memory, though he wasn’t sure what he thought of it anymore.

“When Ross and I were seventeen, and in our last year of school, we came home to find our mother drinking and she was … rambling.” Rupert closed his eyes briefly as he remembered their distress, sensing the trouble that lay ahead. “We tried to sober her up before our father came home. We were worried. He came home and was angrier than we had ever seen him. He was on the verge of hitting her. We think he would have, but Ross hit him first. I was sort of shielding Mum … I didn’t see it happen, but I heard Father hit the floor. Ross ran out. He was so angry … and scared, I think. Mum was screaming. I lifted Father to the chair. He was all right, but bleeding from a cut on his mouth and he was cursing us. I don’t think he knew which one of us it was in all the confusion. I put Mum to bed and Father just sat in the chair and wouldn’t speak.”

Rupert paused, feeling the unwelcome return of the emotion of that night. He breathed deeply as he walked to slow his thoughts. Out the corner of his eye he could see that Athena was listening with grave attention. He continued.

“When they were both asleep, I went out looking for Ross. He’d been gone for hours. I called at some friends’ houses, but he wasn’t there. Then I had this feeling of where he would be and … he was there … standing on the edge of the bluff close to our home where we often used to sit and talk. But it was dark. He had his back to me, and he was weaving about with a bottle of Mum’s scotch that he must have hidden from her. I approached him slowly, I was afraid of what he was going to do … I hadn’t seen him like that before.”

He stopped walking. Athena faced him silently.

“When I was close enough, I called his name. He turned around to face me, but he started to taunt me … moving backwards to the edge of the bluff, his arms up high, and he kept swilling from that bloody bottle …”

He stopped. “Sorry.” In relating that night to Athena, he saw all too clearly where his brother’s trouble had begun. He was never the same after it, and Rupert would continue to curse the bottles of alcohol that became Ross’s constant accessories.

Athena smiled at him sympathetically.

“Anyway, he went on like that for a while and I was just … frozen to the spot. I just kept telling him that I loved him and then, finally, he just fell down on his knees and cried his heart out.”

Rupert’s eyes smarted.

Athena looked down to the ground. He saw it and was grateful. He breathed deeply, conscious that he had spoken for a long time and still had not come to the point of his monologue. He was unaccustomed to speaking about himself at such length.

“I will get to the point,” he said light-heartedly, trying to lift the intensity of the moment.

She looked up and smiled and Rupert thought she brushed his arm. She looked across to a nearby park bench.

“Do you want to sit down for it?” she said. “I think I need to.”

“Good idea,” he said, leading the way and disturbing a flock of seagulls feeding on chips that had been spilt on the ground.

He waited for her to sit before seating himself.

They sat quietly together staring ahead, each lost for a moment in their own thoughts. The river was calm and looked like mercury. A skiff passed by them silently, its rowers grimly intent in their task.

“So …” Rupert laughed as he faced her. “This is going to be an anticlimax. I’ve told you the most dramatic part. I imagined that you would be ticking boxes and taking copious notes.”

“I’ll remember,” she said, settling back into the bench as if in for the long haul. “I’m ready.”

Looking ahead he noted how the water’s surface had been sliced into two even parts, each rippling its way towards the banks. He focused his thoughts and spoke, much slower now.

“I went to him then … to Ross … and held him in my arms while he let it all out. We were just tired of it all you see. It had gone on so long, and we were constantly anxious. Ross fell asleep, probably helped by the alcohol, and I didn’t have the heart to move him. So, we just stayed there, on the ground, by the edge of that bluff. It was quite late, but there was a full moon so I could see most things around me. I could hear the waves crashing on the shore below. It was peaceful. I was wide-awake, holding Ross, and probably thinking about it all … I don’t remember.” He paused while he tried to think of a way to explain what happened next. “What I do remember is that I was looking at a nearby pine tree and I became aware of a … visible clarity … of the tree, of Ross, and, as I looked up and around at the stars, the moon, it was as if … ” Rupert searched his mind for something that would help to explain his experience, “ … as if everything had suddenly taken on a heightened reality. And then …” He took a long intake of air through his nose before continuing. “It all became indistinguishable points of vibrating light. I couldn’t define any one thing from another — not even my hands.”

He stopped abruptly and looked at her, trying to gauge her reaction.

Athena had been watching him intently while he spoke, and her eyes had widened. He thought he saw her shiver.

“That’s not all I’m afraid,” he said almost apologetically.

“Oh?”

“There was something else.” This was the part he was dreading the most. “A voice.” He looked down and could feel himself blush.

“Oh,” she said.

He continued slowly, “When I say a voice, it was … in my head, not something that anyone else would have heard.”

“What did it say?”

“Well … It’s difficult. It was more the feeling that I had … an incredible, indescribable feeling of peace that was overwhelming. I felt like I was physically fusing with everything around me … and I knew that I was being called to serve him.

She looked confused.

Rupert continued. “I knew, well, at the time I thought I knew, that it was the voice of God, wanting, asking me to live my life in his service. There were no particular words I can recall, as I said, more a feeling.”

He had often thought about it over the years, tried to rationalize it, but he had held a deep conviction that the experience, that the voice, was real, not imagined. That is, until now.

“Why would you assume it was an experience of God?”

Although Athena still looked bemused, she listened intently.

“I ask myself that now, but, at the time, I had no doubt that it was God. As the son of a Minister, I had grown up with religion. When I look back, I don’t think I could have thought it was anything else.”

“And so you became a priest. Did you want to? Had you thought about it before?”

“Not really, and … no. But I felt at the time that I couldn’t deny that call.” He stopped for a moment, her silence suggesting that she needed time to digest it. “I told you it would sound trite.”

“No, no. It doesn’t sound trite at all! It’s just, I suppose I would understand better if I had an experience myself.” She considered for a little longer. “But why the Catholics?”

Rupert laughed. “I think I was rebelling against my father. There were several factors. A chance meeting with a Catholic priest.” His heart lifted at the thought of Matthew, his dearest friend and mentor. “An idea about the significance of celibacy, which was probably disguising a resolve not to marry, and yes … some rebellion.”

“What about Ross?” Athena said. “What happened after that incident?”

“That night marked the beginning of a downward spiral. He was angry, with me, of course, for making my decision. He couldn’t understand it and I think he felt that I had abandoned him. He managed to complete an engineering degree and did quite well considering he was rarely at lectures, usually sleeping off a hangover. Then, when we were twenty-five, he met and married Kate.”

He could feel a small surge of anger at the thought of his former sister-in-law. Kate had been a student of Fine Arts at the same university when Ross and Rupert were studying. Finely strung, but talented and creative, she lived the life of a bohemian artist, and Ross had fallen madly in love with her.

“Was it a happy marriage?”

“No. Well, it was at first, but Kate had some problems of her own and she … she didn’t help his problems. They divorced several years ago.”

“And there were no children?”

“Yes. One. Neti, my niece.”

“And she’s with her mother?”

Rupert paused, knowing that this was the root of his anger towards Kate. Though it was obvious that domestic life stifled her, she had had a child with Ross and then abandoned them when Neti was just five years old. Rupert could never understand how she could walk away from her family.

“No. Neti’s with me.”

Athena looked confused.

“Kate left Ross and Neti ten years ago,” Rupert explained. “She broke my brother’s heart. Despite their difficulties, he loved her.”

“So, he was left to raise Neti … and now?”

“I’m her guardian. There’s no one else. We don’t have any other family, and she’s Ross’s daughter, my niece, I should raise her.”

“You can do that as a priest?”

“It’s not usual. But these are not usual circumstances.”

“How’s it going?”

“It’s a learning process.”

“I’ll bet!” Athena laughed.

They sat silently for a while, staring at the passing boat, lost in their own thoughts.