3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

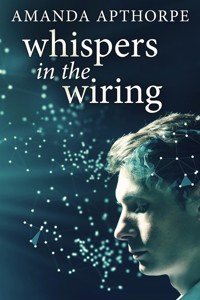

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

After the death of his twin brother, Catholic priest Rupert Brown gains guardianship of his fifteen-year-old niece, Neti.

Burdened with grief and questioning his faith, Rupert tries to recreate a family home for Neti, made more difficult by the sudden return of her mother after a ten-year absence.

When neuroscientist Athena Nevis invites him to take part in her research on heightened religious experiences, Rupert begins to question his life-long vocational choice of the priesthood. Soon, Athena's and Rupert's interest begins to extend beyond their professional relationship, bringing them both face to face with their values and spirituality.

A touching tale of grief, faith and determination, Amanda Apthorpe's 'Whispers In The Wiring' is at its core a story of personal growth, acceptance and finding happiness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

WHISPERS IN THE WIRING

AMANDA APTHORPE

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Acknowledgments

You may also like

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2021 Amanda Apthorpe

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2021 by Next Chapter

Published 2021 by Next Chapter

Edited by India Hammond

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

For Alison

CHAPTERONE

Rupert reached into the top of the wardrobe. His hands groped among the many books and the few items of clothing. When he felt the rough texture of the cloth, he knew he’d found his mark. His fingers traced the hard edges of its contents. Lifting it down he placed it on the bed, smoothing the quilt around it. He sat carefully on the bed’s edge and loosened the cloth to reveal a solid black plastic box and sat back from it, staring at it in quiet disbelief, the fingers of his left hand twisting the plain gold ring on his right. Rupert picked the box up again and held it to him, unable to comprehend that the brother he loved so much was now reduced to an area smaller than a lunch box. He had expected something more fitting for his brother’s remains, but the weak voice of practicality reminded him that he lived in an age of disposability. The absurdity of it struck him and might have brought a smile to his lips were it not for a weight that was dragging at his heart. He wished that he could unburden that weight. He felt it physically, a heavy sensation in his chest that drew strength from his arms and legs and caused his breath to come in sharp gasps and to leave in long, fractured sighs.

He turned the box around until the plastic stopper was facing him — the stone across his brother’s tomb. His thoughts drifted in a black and grey kaleidoscope and came to rest on the last conversation he’d had with Ross. He remembered the pain in his brother’s voice, unsuccessfully disguised by too much alcohol, and the chilling sound of his despondency when he sighed and said that he didn’t think he was of use to anyone anymore.

“But you mean something to me! And to Neti!” Rupert had replied with urgency but also a small amount of irritation. He had listened as he always had. He had told Ross what he meant to him. He just wished that he’d never put down the phone; that he’d kept talking to him. If only he’d known that they would never speak again.

But how could he have known? How many times had those conversations taken place? That instance, like so many others that had occurred all through their lives, caused Rupert to wonder where personality originated. It couldn’t lie in the genes as some scientists claimed — Ross was his identical twin. If it were in the genes then Rupert too, with the help of a whisky bottle, would have tried to obliterate the pain of living and rammed his car into a tree. Or, conversely, Ross also would have chosen the safety of religious life and lost himself in the rituals and self-admonishments in an attempt to suppress the ego.

Rupert picked and prized at the plastic stopper that popped open to reveal the contents inside. No angels at the tomb, he thought ruefully. He held the box up closer to his eyes and could just make out the greyness of the ash against the black interior. His hand and the box dropped to his lap.

“Oh … Ross …”

The weight was dragging at his heart and constricting his throat, preventing him from breathing. The feeling was made worse by his attempt to stifle the sobs that were straining to be released. His mind raced through an assortment of images of his life with his twin — childhood scenes confused with adult conversations, the face of his brother one minute laughing, the next sobbing into Rupert’s chest.

Gathering himself together, he sat upright. He lifted the box again and, tilting it towards him, dipped two fingers tentatively through the opening. The ash felt cool and some adhered easily to the sweat on his fingertips. He withdrew them and stared at them blankly, his mind having shifted to that empty space known to those in shock. Closing his eyes, he lowered his head to his chest and brought the fingers to his head. Lightly touching the space between his eyebrows, he began to apply the ashen traces of his brother to his forehead in a barely discernible sign of the cross.

Remember Man That Thou Art Dust.

CHAPTERTWO

Had only two weeks passed since Marjorie would find Rupert in the staff room spending time between lectures in easy chatter with colleagues? Now, after his brother’s death, he more often slipped quietly into his office and, she imagined, shut the door behind him in relief.

Marjorie knew this was where to find him. She knocked and entered his study at his invitation. He was sitting marking papers by the window. In the ten years that Rupert had inhabited this office, very little had changed. He was an orderly man, sometimes to a fault. As a teacher though, he was renowned for his knowledge and his patience. Marjorie fancied that she could tell more about her staff on visiting their offices than she could by visiting their homes, which for some, like Rupert, was just a room in the College. For most who taught theology here, teaching was their life, and their offices reflected that life. Sometimes they were sad places, especially for the residents, no photographs of family and friends, no impractical presents from children, no sign of other interests or hobbies. However, this was not true of Rupert, and in some ways, this was his contradiction. His office was sparse, but there were photographs, small ones in wooden frames of his mother, his brother Ross, and of his niece, Neti. These did not sit publicly upon his desk, but on the bookshelf across the room. Each photograph, she noted, was angled to take in the others while also facing him at his desk.

He looked up and smiled at her; she was struck by the gauntness of his face — not that anyone else seemed to have noticed, or if they had, no one had commented. Perhaps it was the light diffused by the old diamond-paned windows behind him that made his skin look sallow and his eyes appear haunted. She wished he would turn on the light so that she could appraise him more carefully.

“Hello,” he said.

She stood inside the doorway. There was something about this time of the afternoon that made her feel melancholy, as if life itself might decide whether to continue or not. In the clearer light of the earlier day, everything seemed to have more reality. This College, its yellow sandstone buildings and carefully maintained gardens, successfully gave the impression of all that is solid and established, of order and substance. But in this light, this twilight, the sandstone wall that Marjorie could now see through Rupert’s window was colourless. The students milling at its base looked tired and less self-assured than they had only a few hours earlier. She looked at Rupert, who was making a final correction to the paper in front of him, and, for a moment, Marjorie was struck with a sense of futility, as if all that took place within the College walls — the supposed sense of purpose and commitment — amounted to nothing.

I must be tired, she thought.

Rupert rose from his seat, gesturing towards the two chairs on the far side of the room.

He crossed the room and waited for her to sit before seating himself opposite her.

Marjorie placed the envelope she was carrying on the coffee table between them. She looked into his eyes.

They’re haunted, she thought.

His normally long, thin face was thinner still and pale, almost grey. Marjorie feared for him. Rupert was forty-two and, although he was lean and conservative in his habits, he was of an age at which two of their colleagues had suffered sudden heart-attacks; one of them fatally.

“How are you? … We miss you in the staff room.”

“I’m all right.”

She leaned towards him, her voice dropping a tone.

“How did it go at the weekend?”

There was a pause before he answered.

“Well, we scattered his ashes where he wanted.”

His voice was practical and steady, but she noticed the colour rise in his face.

“That’s about it really … It’s all over now.”

“What about Neti?”

He cocked an eyebrow.

“She made an inappropriate comment at an important moment.”

Marjorie noticed the flicker of irritation on Rupert’s face.

“It’s probably the only way she knew how to cope with it.”

“Yes.”

“How are the two of you getting along?”

“Like any fifteen-year-old and a stuffy forty-year-old might!”

“Your words or hers?” Marjorie said smiling.

A small smile forced itself onto Rupert’s lips.

“Mine. Neti would never use a tame word like ‘stuffy’.”

“When are you moving?”

“Neti’s away with her friend’s family at the moment. I’ll move into the house tonight. She’ll be home tomorrow.”

Marjorie took an intake of air and let it out slowly as she spoke, “It’s not going to be easy … You’ve lived here for a long time on your own.”

“I know, but I lived in the religious community for twelve years,” he offered with hope. He looked down at his hands. “I’m going to need your advice on raising a child — an adolescent, I mean.”

Her eyes followed his to the gold band on his finger.

“Ross’s ring?”

He didn’t look up.

She spoke to his bent head, “Will everything be all right Ru, financially, I mean?”

Thoughtfully, Rupert raised his head.

“Despite Ross’s limitations as a father, he has left a considerable legacy for Neti. It makes me wonder if he knew …”

The air felt heavy between them. She reached for the envelope on the table.

“I thought you might be interested in this.”

She slid the letter from its jacket and held it out to him.

He took it from her. “What is it?”

“A letter … a request from a post-graduate student — PhD, I think, in neuroscience. She is wanting to interview anyone here who has had ‘an intense religious experience’ to use her words. I thought you might—”

“Oh no … no … I don’t think so,” he said handing the letter back to her.

“Just think about it.”

She slipped the letter back into the envelope and placed it on the table as she rose to leave.

He rose with her.

Marjorie paused at the door and placed her hand on Rupert’s arm in a gesture that revealed their long friendship.

“It might be what you need …” she said, “to talk about it again.”

He saw her expression and smiled. “I’ll think about it.”

Rupert closed the door behind her and turned back to his desk, avoiding the envelope still sitting on the table. The marking of papers seemed to be an endless task, made more so by the fact that he had to reread sections of students’ work more often than usual. He found it difficult to focus on the content, and when he did, it seemed to be trivial and irrelevant. He knew that this was unfair, that each student deserved his full attention and to be taken seriously. Since Ross’ death and funeral, however, it was increasingly difficult to assign significance to anything. When Ross was alive, he hadn’t thought that his brother gave his life its motivation, but it now felt that there was little reason to go on without him, except for his responsibility to Neti. He didn’t want to end his life, but he felt that if it did end, it wouldn’t matter. If Ross could go … so could he. He remembered that he had even felt some envy as the coffin was lowered to the flames. He didn’t want to be the one left behind and felt that the greatest void existed in living, not in dying.

He thought about Neti and how she felt. She had given nothing away emotionally in the last two weeks. At her father’s funeral, she sat impassively, studying her nails, although her chin was tucked close to her chest as if to contain anything that might leak from her heart and mind. He felt overwhelmed by the need to protect her but was daunted by the responsibility he was about to take on.

At his brother’s home, that was now to be his own, Rupert poked at the charred logs he’d placed too early on the fire, hoping that something would take. He wanted the house to be warm and cheerful for Neti’s arrival home, but he seemed to be thwarted in his attempts. He wondered whether he should put on some music, or perhaps the television, to create an atmosphere that might alleviate the inevitable silences between them. He decided on the television, which was now creating an uncomfortably chirpy background and made him feel like a court jester waiting in the wings to perform to a temperamental monarch.

He didn’t know what Neti liked to eat, except for the various types of junk food he’d seen her consume with gusto on outings with Ross. A stock-take of the pantry revealed his brother’s absence sharply. Rupert pictured him selecting each item from the supermarket shelf. In the end, the pantry’s contents gave him no assistance; it seemed that father and daughter had lived on three-minute noodles and sauces found in jars with nonsensical names. He resorted to ordering Chinese take-away; he’d found a phone number, along with those of many other home-delivery restaurants under colourful magnets on the refrigerator. Even the simple task of ordering for them both caused him some anxiety. He was becoming acutely aware of his worldly incompetence.

Stepping into his brother’s home had been difficult. He had not been here since the day Ross had died in the accident. Neti had been away on school camp and was due back that day; he suspected that her absence for a week unleashed Ross’s fatal drinking spell. Rupert had waited at the school for the buses to return from camp. She was not surprised to see her uncle instead of her father — Rupert occasionally had to fill in when Ross was away on business trips. He remembered that she was flushed with excitement about the trip and full of stories about friendships made and lost; he also remembered, too vividly, her face when he told her about her father — how she turned a ghostly white and sat back from him, suspicious of his motives in telling her something like that. She had kept that distance ever since.

On this day, he would attempt to recreate a home for her. Concerned parents of Neti’s friend had asked to take her in immediately until living arrangements were sorted out and so little had been disturbed at the house. When Rupert came in, the door to Ross’s bedroom was closed. Inside, the room was tidy and the bed made. Ross’s slippers were lying just inside the door and were askew, as if someone had thrown them in quickly and shut the door. Rupert had stared at them, too easily picturing them on his brother’s feet. He slipped off his own shoes and stepped into them. His breath caught in his throat, and he quickly took them off again and shut the door behind him.

One hopeful flame burst from the embers in search of loose, dry bark. Rupert stood, flexing his body to ease the strain on his lower back. He turned around and scanned the lounge room, trying to imagine he was looking at it through Neti’s eyes. Lamps on, television on, fire almost glowing, flowers in the vase on the coffee table. Is this what it would have looked like when she came home from school to her father? Too often she would have found Ross in a state of depression, with alcohol on his breath when she kissed him hello. No doubt Ross had tried to hide it from her. He was a good and loving father, but the eyes and ears of a fifteen-year-old are acutely tuned to the fraudulence of adults.

Leaving the residential college at the university where he had lived for ten years had been much harder than Rupert had thought. When he’d arrived, he’d been an eager thirty-two. He was more than ready, after twelve years in the seminary, to share his knowledge and his faith with his students — and he was satisfied with his calling. Occasionally over the following years, he’d fantasized about living in what some people called the ‘real world’ — marriage, children, mortgage; he wondered if he was missing out on something. Very often though, these were fleeting fantasies. His role as priest, and more particularly as confessor, exposed him more than most to the darkness of the human heart and, although he felt a genuine compassion, he could not empathize. Nor did he want to. Instead, he found himself wanting to distance himself further from the everyday human experience. That marriage and family life were not for him was reinforced by Ross’s bitterly unhappy marriage and separation, but it had its roots much earlier in his own unhappy childhood.

When he’d closed the door to his room for the last time the previous day, he knew he was also closing a significant chapter of his life. To the outside world, his life would not appear to be much different; he would continue lecturing and carrying out his duties as the College chaplain. But his internal life was undergoing changes, the nature of which he could not determine, nor did he want to — he sensed that danger might be lurking there.

Rupert turned back to the fire, his eyes flicking along an assortment of photographs on the mantelpiece. From the corner of his eye, one of them caused him to start. It was a picture of Neti and Ross, but he had thought for a moment it was himself. Although they were identical twins, neither could really understand the difficulty others, even their own parents, occasionally had in telling them apart. Looking now at this photo, he was taken aback. What would Neti think when she walked into her home and saw him? A surge of panic went through him. She had always known him, seen father and uncle together, and she had faced him during the terrible weeks of Ross’s death, but tonight was different. He was to be her guardian, living with her as her father had, and this was the beginning of that life together.

He heard a car door close in the driveway and the car leave. What was he to do? Open the door to greet her wearing Ross’s face? Should he be doing something? Maybe with his back to her, humming nonchalantly, so that when she said hello, he would turn his head slowly, allowing her to adjust to the sight of him? Before he could decide, she was opening the front door. He bent down to the fire and stabbed at it repeatedly with the poker and began to whistle a cheerful tune. He heard the door close loudly behind her, announcing her arrival in a clear statement. His stomach lurched and the set of his jaw would no longer allow him to whistle.

Neti seemed to be unaware of him standing by the fire when she walked through the lounge-room from the front door. Although she must have known he would be there, she didn’t seem to be looking for him. Instead, she headed resolutely to the kitchen, her gaze fixed ahead, the stiff movements of her body betraying her tension and giving her a slightly uncoordinated gait.

“Hello,” he said from behind her. He noticed that her hair was now a combination of bright red and brown streaks that had been cut into short, aggressive spikes.

“Welcome home.”

She froze mid-stride and seemed to be debating whether to keep going. She turned her head slowly, the rest of her body still facing its preferred direction.

“Hello.”

She said it without raising her eyes to him. The first of many silences fell between them, filled only by the drone of the television. He was glad now that he’d put it on.

Rupert thanked Polly’s father who was waiting at the door and noted his look of sympathetic concern as he handed Rupert Neti’s bags of clothing.

“If there’s any way that I can help …”

Rupert thanked him, sincerely wishing that he could.

When he returned to the lounge room, Neti was in the kitchen.

“You haven’t eaten, have you?” he asked too cheerfully. He continued quickly, trying to stifle the silence that answered him. “I’ve bought some Chinese food.”

“I’m not hungry.” Her eyes lifted to his. There it is, he thought, the look of panic and pain. But it was fleeting and was instantly replaced with a look of contempt.

He had imagined that, on her return home, she would run to him as she had as a little girl. He had pictured her crying into his chest as he consoled her. Instead, she faced him coldly, half a room separating them.

“I’m going to bed.”

She turned on her heels, steered away from the kitchen and headed up the passage to her bedroom, slamming the door behind her.

Almost as soon as it left her hand, Neti regretted the force she had applied to the door. She threw her bag into the corner of the room and fell face down on the bed, burying her head into the pillow. She flipped onto her back and lay staring at the ceiling looking for the old familiar patterns in the cornices; the tiny imperfections that were like secret messages from a master craftsman of an older time. Normally she found comfort in the shapes and chips that took on the appearance of animals and faces of imaginary people who had been her childhood friends, but tonight she couldn’t empty her mind enough to allow them to manifest.

She rolled onto her side to look at the streetlights through the window, but nothing engaged her there. She rolled to her other side and let her eyes wander over the bits and pieces on her bedside table. She studied her collection of small china horses; rock pieces she had collected with her father on Sunday drives, each piece clearly defined by the light of the lamp that her uncle had put on earlier to greet her home. Standing out sharply from these was a small red bird made of cloth, stitched with gold and coloured thread, a Luck Bird her mother had sent to her many years ago after one of her many trips to Thailand. That’s what her father had said anyway, with a note of sarcasm in his voice. She must have sent it not long after she left them, but Neti had not received anything more in ten years. She often wondered if her father had intercepted the gifts and had, a couple of times, looked in his room for unopened parcels and letters addressed to her. She had never found anything but was certain that they must exist. A mother would not just forget about her child — she was sure of that.

Neti propped herself up and took the bird from the table. She ran a thumb gently over its surface, circling its large woven eyes over and over. She could not remember much about her mother, but her father had given her a few photographs of happier times when they were a family. Still holding the bird, she opened the drawer of the table and took out a black book with an inset lock. She rummaged through the graffitied pencil case on the floor and produced a tiny key. From the back of her diary, she took out a photograph. It was of herself as a newborn resting in the crook of her mother’s arm, her father sitting beside them. She dwelled momentarily on his image before placing her thumb over his face and, concentrating on that of the woman staring back at her, looked for similarities in her mother’s face to her own. She decided that, yes, she could recognise some common traits; here, in the downturn of the eyes, there, in the soft cleft of the chin.

What had happened between her parents? She had asked her father, but he became subdued and would only say that her mother found it hard to adjust. Adjust to what? Neti felt that he had waited for his wife to return, and so she too lived with that thought. She placed the bird on top of the photograph, its body obscuring her father’s face. Her mother would come home, she thought. She must come home now.

Still standing with his back to the smoking embers, Rupert winced as the door slammed. There was a moment of déjà vu — of walls shuddering as doors slammed and of malignant silences that grew between his feuding parents.

A long-buried but familiar knot was forming in his stomach. He automatically assumed the deep-breathing method he had devised in his childhood as a coping strategy.

What was he to do about Neti? His uncertainty rooted him to the hearth. Rupert forced his feet to cross the room to the passage and to her door. He raised one hand, knuckles bent for the knock, but drew it away again before making contact. He leaned forward, resting his forehead on the cool wood while he debated his next move. He thought he could hear her sob in an otherwise silent room. He straightened himself and raised his hand again only to see the lamplight go out from under the door.

He turned back to the lounge room, switched off the television, turned the armchair to the face the fire and sank into it.

For a long time, Rupert sat staring ahead, his mind in such a confusion of thoughts that, if asked, he would have said that he had no thoughts at all. He hadn’t slept well for the week leading up to this day and after a few hours fell into a light sleep. His body twitched as his mind sank through the levels of sleep. At its deepest point, his breath came evenly but his eyes darted behind his closed lids.

Ross is here sitting beside him, a glass of whisky in one hand, cigarette in the other. Rupert is happy to see him but is not surprised. They have often sat here together. There is one difference this time — Ross is dead. His presence, though, is confirmation that life after death exists and Rupert is relieved.

“What is it like?” he asks with anticipation, only vaguely surprised that Ross is still drinking.

“It’s all right … Nothing in particular.”

And there is that all too familiar desolation in Ross’s voice. He swills his glass and takes a sip, the clink of the ice echoing through Rupert’s growing emptiness.

His misery, heightened by the chill of the room, woke him. He opened his eyes and stared blankly ahead while his brain tried to reconcile the objects in his brother’s home with the expected sight of his old bedroom. He felt drugged from a sleep that had brought him no relief. He placed the screen in front of the fire, switched off the lamp and retired to the small guest’s room at the rear of the house.

CHAPTERTHREE

The sound of the telephone ringing jarred the silence of the office and caused Rupert’s pulse to quicken. He had become suspicious of the motives of the telephone and the sound of a knock on the door — they could only bring bad news. He wondered if he would always be like this. What had once been innocuous enough sounds seemed now to be loaded with ill-meaning.

Reluctantly, he picked up the receiver, “Hello.”

“Hello.” The woman’s voice at the other end of the telephone sounded cheery, and not the bearer of bad news. He relaxed a little.

“This is Rupert Brown.”

The caller introduced herself as Athena Nevis.

There was a pause that suggested to Rupert that he should know who she was. She must have heard his hesitation as she continued quickly.

“I’m researching my PhD at this university, and you volunteered to be a subject?”