7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

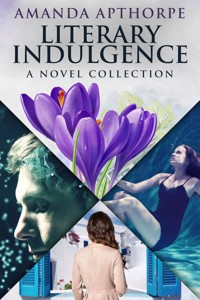

A collection of four novels by Amanda Apthorpe, now available in one volume!

A Single Breath: Obstetrician Dana Cavanagh receives hate mail after the court's verdict of not guilty for the death of her patient Bonnie. While sifting through the letters, she receives a cryptic message with a tiny marble stone from Greece. Accompanied by her sister, she travels to Kos to follow the mystery of the letter. With strange ghostly appearances and two more letters, Dana wonders if she can persist in her crusade to clear her name and find the truth.

Hibernia: Gallery co-manager Audrey Spencer finds herself stranded on Hibernia, an island off the mainland coast, and is helped by strangers before returning to her urban life. Unable to shake her memories of the island, Audrey returns with her parents and best friend, Poppy, to consider a different way of living. However, she faces threats to the island's ecosystem, her husband's greed, and her uncertain attraction to Quin O’Rourke, leading her to draw on her strengths and help save the island with the unlikely help of the saffron crocus.

One Core Belief: Delfi Kazan longs to escape her small island and make it big in Athens as a soap opera star, but her arranged marriage to handsome engineer Nikolas offers a glimmer of hope. However, Nikolas is still pining over his ex-fiancé and has lost his passion for city life, leaving Delfi to toil away in his family's taverna. As she struggles to find a way out, an offer and a seduction present themselves, but will they lead her to her dreams?

Whispers In The Wiring: After his twin brother's death, priest Rupert Brown takes guardianship of his teenage niece, Neti. Struggling with grief and his faith, Rupert attempts to create a home for Neti while dealing with her estranged mother's sudden return. A neuroscientist, Athena Nevis, invites Rupert to participate in her research on religious experiences, leading him to question his lifelong vocation. As their relationship evolves, Rupert and Athena confront their spirituality and values, ultimately discovering personal growth, acceptance, and happiness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

LITERARY INDULGENCE

A NOVEL COLLECTION

AMANDA APTHORPE

CONTENTS

A Single Breath

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Acknowledgments

Hibernia

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Acknowledgments

One Core Belief

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Acknowledgement

Whispers in the Wiring

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2023 Amanda Apthorpe

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2023 by Next Chapter

Published 2023 by Next Chapter

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

A SINGLE BREATH

Dedicated to my parents, Sid and June Jones,

and my sister, Andrea Madeline Jones

I had become only too aware that life’s beginning and its end hinged on a single breath, as though the rest was conducted in its pause.

CHAPTERONE

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

The ceiling of the cabin sagged so low that I could measure its distance to my face with a wide-fingered handspan. A cold light from the bathroom cubicle ricocheted around the walls and reflected off the panels above my nose. Where they met, someone had picked at the seam like a child at a scab. With each pitch and toss of the ferry, diesel fumes seeped through its pores.

There was no sound from the bunk below. My sister, I assumed, was sleeping peacefully, but I needed the comfort of her enthusiasm. In the space left to me, I contorted my body so that my head and torso hung over the bunk’s edge.

“Madeleine. Are you awake?”

There was a low groan and the sound of the bunk springs creaking as she rolled over.

“What?” Her yawn was thick with sleep.

“What are we doing here Mads?”

No reply, just a soft snore at the back of her throat. I rolled back to stare again at the ceiling’s ragged seam. A dog barked in a cabin somewhere further along the deck.

In the darkness of what I feared would be our watery crypt, I doubted the wisdom of this journey.

CHAPTERTWO

It had begun with the arrival of the first letter. What I remember about that day is tinted with soft shades of autumn. It must have been warm because I was sitting in my courtyard reading the newspaper. I looked up, drawn by a tone in Madeleine’s voice.

The air seemed to shimmer around her strong and solid body as she moved towards me. My own depleted frame would have cut that air like a dulled blade. Her arm was raised as if she was about to slap the letter, she held on to the cast iron table and her face was pinched with familiar concern. When I took it from her, I saw that my name and address were written in Indian ink in an old-fashioned hand. She sat as I broke the seal. Inside was a sheet of parchment paper folded over. As I opened it, a small stone rattled on to the table.

“What does it say?” Madeleine nodded towards the note and shuffled closer in the protective way she had adopted in those months. She picked up the stone and rolled it in her fingers.

The letters of a foreign language were written in the centre of the page.

“It’s not in English,” I said and passed it to her. She tried to sound what looked to be three words and shrugged as she handed it back. I studied it more closely.

“It could be Greek.” The envelope was face up and I took in the postmark. “It’s been sent from Kos,” I said.

“Where?”

“A Greek island near the Turkish coast.”

My sister’s eyes shone in response. She was always eager for mystery, a trait that had led her into more daring adventures than I would ever contemplate. I picked up the stone and held it in one hand beneath the table. I returned to reading the newspaper, feigning a lack of interest in the letter but in truth I felt a small, quiet dread.

“What do you make of it, Dee?”

I looked up and met her eyes. “It’s probably another hate letter.”

She picked up the envelope and seemed to be measuring the weight of the words with a small movement of her hand.

“I don’t think so,” she said. “It’s different from the others. Why be cryptic about hating someone?”

“Well, don’t read too much into it,” I said, flicking over a page of the paper with a finality that drew on my status as her older sister. The palm of my hand throbbed around the stone.

* * *

That night I woke at 2.20. My mother had once told me that it was the hour that people are most likely to die. I had believed her, but in all my years of medical practice had not seen any evidence, though my work was normally concerned with life’s fragile start.

In more recent times, I had become only too aware that life’s beginning and its end hinged on a single breath, as though the rest was conducted in its pause.

It was another dream that had woken me and the memory of it continued to resonate. For a while, I lay beneath the covers, allowing it to filter through.

There stands a man, his hand outstretched to me. Snakes writhe at his feet as they slide from a narrow pink vein embedded in a marble pedestal. I watch in fascination, then in horror, as I realise that it is not marble, but the body of a lifeless woman. The pink veins become blue. I turn at the feel of another’s breath and see a woman, her hair braided. “Who are you?” I ask. She is about to speak her name…

By 3.30, I’d poured my third cup of tea. If I were Madeleine, it would have been peanut butter eaten by the spoonful to relieve anxiety. I wanted to call her but resisted. Aside from the late hour, I couldn’t bear her analysis of the dream and suspected that I already knew some of what she would say – the snake was my kundalini energy finally releasing. We thought differently, but what kept me at the table, breathing long draughts of tea-steam through my nostrils, was that Madeleine and I would agree on the significance of the dead woman.

At 4am, a two-week-old newspaper that I had saved was spread before me. I knew what was in there but had never opened it until that moment. At page five, I saw the small article, the shards of my life collected into 100 or so words. The gist of it read: Verdict not guilty; professional integrity restored; the plaintiff, struggling to reconcile the birth of his daughter and the death of his wife; the wife… dead from unforeseen causes.

I reread the article and said the wife’s name aloud – Bonnie – like an incantation. I wished that she hadn’t had a name so that it might hurt less.

Exonerated ofall blame – did all she could… But the words didn’t provide me with any comfort.

“It wasn’t your fault!” Madeleine had said and her expression had been desperate with the fear that I could have a breakdown.

How is a person meant to come to terms with being implicated in the death of another?

Leaning on my old oak dining table, a favourite of the “glory box” I abandoned when Julian left, I got up, physically and mentally aching, and went to the bookshelf. A well-meaning friend had suggested that I record my thoughts after Bonnie’s death as a kind of therapy. I followed her advice, looking for anything that would ease the pain of it and the case brought against me by Bonnie’s husband.

I took the envelope that had arrived that day from my pocket. The stone dropped into my hand as I looked at the note. Although I couldn’t understand them, the words made me uneasy. I slipped it between the pages of the diary. From the drawer of the desk, I took out my jewellery box. Apart from a string of pearls and a jade scarab beetle, a souvenir from Madeleine’s trip to Egypt, there was little else inside. Before the stone joined them, I studied it as it lay in my palm. It was no more than two millimetres thick, but it felt cold in the warmth of my hand. It was either marble or quartz and had a thin, rust-red vein that made it blush.

At 5am and feeling soothed, whether by the tea or exhaustion, I climbed back into bed. I slept then, a dreamless sleep and longer than I’d slept for months. When I awoke, I lay beneath the covers as I had done so many mornings since Bonnie’s death.

Refreshed, I grew restless quickly and felt a return of an old eagerness to begin the day. I showered with a sense of purpose and felt a craving for a coffee and croissant in Chapel Street – I hadn’t done that in a long time. The gate’s click sounded a note of approval as it closed behind me.

At my regular café, I bypassed the pavement tables; the cooling autumn weather was beginning to creep into my toes. From a seat by the window, I looked out, regretting that I had missed the sun’s warmth and the hot, lazy days that had come and gone that summer when I’d barely left the house.

Deb came to take my order and smiled. “Haven’t seen you for a while, Dana. Been away?”

“Yes,” I lied but didn’t offer any more. She didn’t ask.

“Lucky you. I could do with a break… maybe the Greek Islands,” she whispered close to my ear before she left to seat a couple who had just walked in.

Before long, I found myself in the travel section of a local bookshop looking for a practical guide to Greece. The little I knew about Kos had come from my fruiterer, Kym, who would become misty-eyed when he’d spoken of the home he’d left 20 years earlier. From his description, it sounded beautiful, as home does when you’re far away and feeling nostalgic.

There was nothing specifically about Kos, but I thumbed through the contents of a Lonely Planet guide and found it. “…third-largest island of the Dodecanese… five kilometres from the Turkish Peninsula of Bodrum…” I scanned its history. “Hippocrates, the father of medicine, was born and lived on the island.” Hippocrates.

There was a small grip of pain in my solar plexus that I could no longer distinguish as physical or emotional. I recalled how proud and emotional I had been when I swore his famous oath, and in particular the line: “I will follow that system of regimen, which, according to my ability and judgement I consider for the benefit of my patients and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous. I will give not deadly medicine…”

Bonnie’s stricken and pleading face swam in front of me, and I felt again the shock of the first hate letter that arrived in the days after her death: “EVIL. MURDERER.”

CHAPTERTHREE

Madeleine’s snore caught in the back of her throat, and I heard the springs groan as she sat up suddenly.

“Are you awake, Dee?”

“Yes.”

“Have you slept?”

“No.”

“Me neither.”

My eyes rolled to the ceiling. “Mads, I’ve been thinking…”

“Yes?” Her voice sounded guarded.

“That we’ve made a big mistake.”

There was silence from below. An expert now at contorting in small spaces, I leaned down, inverting my head towards her. “Mads?”

“Why, Dee? Because the sea’s a bit rough?”

“A bit rough! No, it’s not that, it’s just… the whole thing is… crazy. Why are we here?”

“No, it’s not crazy. We’re meant to come.”

“Really. Please don’t tell me: ‘It’s our destiny.’”

“But it is.”

I leaned further over the bunk’s rail, “Oh Mads, come off it. Based on what? A letter we don’t understand. A small piece of marble that could be a chip off a headstone – a warning!”

Silence again, then the creaking springs as she got out of bed. She staggered to the bathroom trying to maintain her balance as the boat lurched sideways. As she shut the door, I was left in the darkness. I flipped on my back, feeling guilty that I was all but blaming my sister. After all, I was the one who had organised this trip.

* * *

Outside the bookshop, I had paused to consider my next move and stepped aside to allow a mother with a baby in a pram to pass me on the narrow footpath. Tucking the Lonely Planet guide under one arm, I walked behind them, trying to prevent my thoughts from taking their familiar diversion into bleakness. Instead, the bright fluorescent lights of a travel agency drew me in and a friendly glance invited me to the counter. A young woman whose name tag read Karen finished tapping at the keyboard and swivelled to give me her attention.

“I’m thinking of going to Greece,” I said.

“Return?”

And then, surprising myself again, I answered: “One way.”

* * *

When I told Madeleine what I had done, her reaction caught me by surprise.

“You’re leaving next Friday!” she said, unable to disguise the disappointment in her voice. She had been my constant companion in the preceding months, almost my carer.

“But you’re the one who suggested I go,” I reminded her.

“Yes…” Madeleine studied her fingernails.

“Oh, and by the way…” I tapped the table and spoke to her hands. “If you can arrange the time, there’s a ticket on hold for you, too.”

“Are you kidding?”

I smiled at the memory of that moment.

“No, I’m not kidding,” I said and touched her fingers. “I just want to thank you. You’ve been really great, Mads, and I don’t know what I would have done without you.”

“You’re my sister.” Her eyes looked dangerously moist.

“So that’s a yes?” I said, as I went into the kitchen. I took a deep breath as I filled the kettle.

“Mm, let me think…” Madeleine called across the kettle’s hum. “If you insist.”

“I do.” I smiled into the two cups in my hand. “Your passport’s still valid?”

Her head appeared around the kitchen doorway. “Yes… I’ve got to go.”

“Where?” I asked.

“Home… to pack!”

* * *

In the bathroom cubicle, I could hear Madeleine cursing the paltry toilet flush. When she opened the door, the light was like the flash of a camera capturing my misery on the top bunk of a dying ferry.

She rummaged through her suitcase without speaking and returned to the bathroom, shutting off the light again in a clear statement of irritation. Blindly, I reached to the panels above my nose and gave them an equally irritated shove. My thoughts returned to the days before our departure. Although I had been putting it off, finally I made the telephone call I had been dreading.

“Dana… how are you?”

My eyes smarted at the sound of Ruth’s voice. As chief of staff, she’d had a tough time during my court case. She’d never wavered in her support of me, despite the media’s attempts to blacken the hospital’s reputation. I had to compress my lips before replying.

“I’m well,” I replied then came quickly to the point. “Ruth, I need time…”

Before I could finish, her soothing voice slid between us.

“Of course… I agree. How long would you like?”

I hesitated, the generosity and the security of what she was offering was tempting.

“I need to resign.”

There was a sharp intake of air at the other end. “Dana, please reconsider. You could have six months… Take a year if you need it.”

I paused, tempted. “I think it’s the best thing, for me and for the hospital.”

“I know what’s best for this hospital, and you’re a significant part of that.”

“Thank you, Ruth. It means a lot to hear you say that. I’ll never forget what you said in my defence.”

“I’ve worked with you for 10 years. I meant every word of it.”

“I’ve… lost the energy for it, Ruth, and the confidence, no doubt.”

“That’s to be expected, Dana. Give yourself some time.”

“I am,” I said with false conviction. “I don’t know how long it will take, so it’s best this way.”

She was silent for a moment. “I’ll accept your resignation, if you insist,” she finally conceded. Her voice, always calm, was gentler still. “But there will be a place for you, if you change your mind. I’m just so sorry this ever happened to you. God bless, Dana.”

As I said my goodbye, I wondered if I had acted too hastily and felt shaky with uncertainty. I was leaving my work, I was leaving my home, and I didn’t really know why. I rang my parents. They were surprised to know that both their daughters would be away for an undetermined length of time.

“It’ll be good for you, darling,” my father said, and I felt the soothing balm of his love. He didn’t question my decision to leave the hospital and I was grateful. My mother was less impressed.

“At least you’ll be together.”

I should have known that she would bring me little comfort.

CHAPTERFOUR

As I was packing, Madeleine arrived with travel gadgets – blow-up pillows, eye masks, drink bottles, lip salves that spilled across my dining room table.

“Freebies,” she announced, “from one of my clients.”

“No problem going away?”

“James can handle the business with his eyes closed.”

Madeleine had built her landscape-design business to a level that she now employed staff.

“I’ll probably become obsolete,” she added.

“Hardly,” I said, and meant it. My sister was the creative and business genius behind Gorgeous Gardens.

“So…” She arranged the items on the table distractedly. “I didn’t ask you what you found out about Kos.”

“Not much.” I told her the little I knew.

She rifled through her handbag to produce a notebook that she waved at me.

“What’s this?” I took it from her.

“The fruits of my own research.”

I was surprised and she saw it on my face.

“Well,” she said to my crooked eyebrow, “I didn’t think you were up to it and…”

“You were.” I laughed, grateful that my sister was predictably unpredictable.

* * *

The bathroom door opened. Madeleine paused, forming a striking silhouette in the door’s frame. “Let’s get out of here,” she said, but I couldn’t see her lips moving and the statement was strangely unsettling. Obediently, I slid from the bunk and dressed.

We took our chances with the unwelcoming crew and other passengers. The engines ground down and the ferry slowed its pace. From the windows of an almost-deserted lounge on an upper deck, we could see a smattering of island lights. The voice over the loudspeaker crackled that we were arriving at Kalymnos. Peering into the dark as the ferry went astern to dock, we could see an old fort tinted by amber lights brooding above the port. Only a dozen or so people disembarked and were swallowed by the night at the end of the pier.

“Not long now,” I murmured, as much to myself as to Madeleine. She didn’t answer.

* * *

A sigh of relief had escaped me when we’d finally boarded the plane to Greece. Farewells weren’t my strong point, and I was irritated by my mother’s sudden display of affection. On the way to Singapore, Madeleine was hyped. By the time we left for Athens, she’d burnt herself out. I shared her eagerness to leave Melbourne, and in fact my life, but at the same time it felt as though I was running away. I’d always taken pride in my ability to complete whatever I began and to go an extra step.

My father, though encouraging and proud of my achievements, would, in his most diplomatic way, suggest that I take things a little easier.

“You’ve achieved so much, Dana. What more do you need to do?”

I appreciated his concern, but I didn’t feel that I could ever push myself too far. I thrived on the challenge of learning more, especially about my profession, and I thrived on success. Leaving felt like admitting defeat, and I wondered if I should have stayed to face my critics and resume my work. Somewhere along the way, though, I’d lost the inclination to do so.

On that long flight, my thoughts drifted to the day that changed my life, as they had for nearly every minute of every day for months. While Madeleine slept, I tried to steer them away, but the energy required was draining. Over and over, I had replayed the events of that day looking for something I might have missed – a sure sign of my guilt or, and I hated to admit it, someone else’s – but there was nothing I could pinpoint, and the events had become distorted with time.

Everything about that day seemed to be wrong, even ominous, though it was a feeling born in retrospect. I’d had my own consultations and a delivery; I’d assisted two others, one a difficult birth and the other a seriously premature baby. After 14 hours without a break, I was tired. Just as I was getting ready to go home, Bonnie, one of my own patients, was rushed into Emergency with a profuse haemorrhage. Even though I was well used to the sight of blood, this time it shocked me and, for weeks afterwards, it ran as a stream of plasma with dark, malevolent clots that tinted my dreams.

I remember throwing aside my bag, raging with frustration when the rubber gloves curled in my palm as I hurriedly pulled them on, and I remember Bonnie’s husband, grey with panic. Bonnie needed an emergency caesarean, but the anaesthetists were tied up with equally urgent cases. I had no choice but to administer the anaesthetic myself, but I couldn’t place the tube in her throat. Bonnie’s strangled gasps for air haunted my days afterwards.

From that point, my memory became blurred with time and shock. In the dreams that followed, I forced the tube deeper and deeper into her throat. In those dreams, Bonnie’s eyes watched mine with unnerving attention, in others they pleaded with me to save her life. By all accounts, I acted swiftly and competently – that was the verdict, based on the testaments of those who had been present – but I wasn’t convinced. Bonnie died from asphyxiation and her daughter was born soon after.

I leaned back into the seat, feeling the familiar despair rising in my chest. Deep-breathing techniques only pushed it further into my viscera. I fumbled for the bag I’d stowed beneath the seat and took out some of the material Madeleine had collected for research – two slim texts and some pages of notes she had jotted down from heavier volumes in the local library.

I opened one of the books, a treatise on a selection of the writings of Hippocrates and thumbed through its pages. The introductory section was academic and tedious, but the pages that followed were a collection of letters and speeches attributed to him.

On the left-hand-side of each double page, the text was written in Greek – Ancient Greek, I reasoned, and the English translation was written on the right. The early part, I read, was a plea from the people of Abdera to Hippocrates to heal their revered Democritus because they were afraid that he was going mad. But Hippocrates suspected that Democritus was showing the signs of attaining greater wisdom, the outward signs were being interpreted as madness. I wondered if my own outward signs over the past few months were consistent with some form of mental derangement.

I read on as Hippocrates recounted a dream: “I seemed to see Asklepios himself… snakes accompanied him. I turned and saw a large, beautiful woman with her hair braided simply… ‘I beg you excellent one, who are you and what shall we call you?’”

I was stunned. Though a particular style of language was used, the woman in Hippocrates’s dream resembled the one in my own. I reread the passage to convince myself that I was being fanciful, that I had latched on to one or two elements – the snake and the woman that could be represented in a million people’s dreams.

The more I read it, the more profoundly it affected me. From the bag, I took out the letter from Kos and laid it on the tray in front of me. I ran my finger slowly down the Greek translation of Hippocrates’ dream carefully comparing the Greek letters with those on the page of the note. In Letter 15, I identified them.

Madeleine stirred and opened her eyes, becoming alert at the sight of the letter and open book.

“Find something?”

“Mmm…” I steadied my breath. “Have a look at this.”

I told her about my dream and what I’d found in the book. She sat up, excited, but not surprised. Nothing was a coincidence to my sister.

“Which parts of the dream do the Greek letters parallel?” she said, shifting in the seat.

I read aloud the preceding translation: “And what shall I call you?”

And there were the three words of the note: “‘Truth,’ she said.”

My hand trembled and Madeleine placed hers over it as she had when the first of the hate mail had arrived before my exoneration.

CHAPTERFIVE

Athens’s toxic pall had been cleared by a persistent wind from the Aegean Sea. From the plane the city spread broadly to the sea and to the mountains behind. Like most tourists, we wanted to see the Acropolis and Parthenon, and at different times, we each thought we had seen it first. There was no mistaking the real thing when it came into view. It seemed that everything modern beneath could never equal it.

We were stiff from the flight and flustered from being constantly jostled as we waited for our luggage. Finally, we boarded a crowded bus for the port of Piraeus. On the wharves, assaulted by the blast of ships’ whistles and the constant smell of diesel, we bought our tickets to Kos at a derelict box where an elderly man in a once-white singlet sat slumped on a stool. As he spoke, I was fixated on the stains beneath his armpits. The ship would be leaving in 10 minutes, we were told in awkward English, a fact that Madeleine noted as a sign that this journey was “meant to be”.

We eyed the docked ferries with approval – Minoan, Blue Star. They were big, modern and looked sleek and beautiful in the sun and I felt satisfied that we had elected to take a ferry rather than a connecting flight. This was my concession to a new way of life, to being more spontaneous and savouring the moment. Everything seemed to be falling into place.

Our ferry was the furthest away. When we got closer, we stopped and gripped each other’s elbows. A small gasp escaped Madeleine’s lips. The ferry was small, old and ugly and my mind spun at the thought that we were to spend 12 hours on it. Madeleine became subdued. Her adventurous nature did not include sinking into the sea in a rusty boat.

“It might be better aboard,” I said, as much to boost my own morale as hers. It wasn’t.

“But I’m sure the crew will be friendly,” I added, as we walked up the gangplank.

They weren’t.

On board, we ate a hasty meal of limp salad and sour feta cheese as soon as the kitchen opened and then slunk down to our cabin in the hope of oblivious sleep. The Aegean Sea in late April was wild and, I discovered, on the top bunk, with the ceiling edging ever closer to my nose, that it was not just claustrophobia I was suffering from, but a literal sinking feeling that we were headed into danger.

* * *

In the dark, Kos looked even more sinister than Kalymnos. We waited on deck with the other eight passengers due to disembark; two women, one with a teenage son and the other carrying string bags full of groceries, while the rest were men of varying ages.

A thick silence rested over our heads as we waited for the gangplank to be lowered. When it was, the others walked purposefully into their lives, leaving us to the mercy of the accommodation touts.

CHAPTERSIX

KOS

Hunger woke me. When I opened my eyes, it took some time to adjust mentally to the unfamiliarity of the room before the events of the early morning fell into place.

Surviving the ferry had given Madeleine a renewed appreciation for living. Confidently, she had steered us past the touts and into the dark at the end of the dock; I’d been grateful for it – my own attempt at being intrepid was rapidly fading. But when the hotels she’d circled in the Lonely Planet guide greeted us with firmly secured doors, her confidence had waned.

In a final attempt at leadership, but too tired to speak, I indicated with my head towards a park bench on the foreshore, visible under a solitary streetlight. We removed our packs with a thud and sat down heavily.

Across the still water, the harbour lights of Bodrum glittered and, above it, in a sky the blue of a royal robe, a sickle moon and star shone in a stunning cliché. We sat in silence, absorbing the beauty of it.

There was a flurry of movement behind us – a car screeching into the curb, an elderly man and woman almost falling out of the front seats. She strode with surprising agility ahead of him and was turning pages in a catalogue before she had even reached us. Stultified from lack of sleep, I motioned to Madeleine to follow them.

The back of the old Renault was crammed with papers, small boxes and clothing that had been shoved aside to allow room for tourists’ backsides. Madeleine and I sat low to the ground while the couple in front seemed to be perched in the air. I have no memory of the husband’s face, just a sense of his anxiety under the command of his wife. The greying hair beneath his bald spot sat unevenly over his collar, made worse by the tilt of his hunched shoulders.

In the rear-view mirror, I glimpsed sad and apologetic-looking eyes. He ground through the gears and the car finally took off, though there was an odd feeling of wading through thick water. I relaxed back into the peeling leather of the seat. Exhaustion released me into their hands and a sense of recklessness.

Why stop now? I thought.

* * *

After only 10 minutes, we turned into the drive of a modern complex and drove past a swimming pool to the back of the building. The rest is a tired blur of choosing beds in a small but tidy unit, of dropping luggage and climbing, fully clothed, under the bed covers.

With my chin still tucked securely beneath the stiff sheet, I scanned the room. In the other bed, Madeleine’s back rose and fell in a calm sleep. To my left, large glass doors opened on to a small but functional balcony. Beyond the glass was a barren land, covered in stones and small, dense shrubs in a limited range of brown and olive green. Scattered here and there were new housing projects that were in various stages of completion, but nearly all were a white that screamed from the brown landscape surrounding it. I imagined that, from the air, these building might look like the droppings of a giant prehistoric bird. In its raw and uncontrived way, it was beautiful.

Smudges on the glass doors distracted my attention. When I focussed on them, their random placement seemed to order themselves into an opaque and transparent mosaic that drew forward the memory of another dream I’d had in the early morning.

Before Bonnie’s death I remember having only dreamless sleep. Since that day, I had come to feel that I was living part of my life caught somewhere between the vivid world of dreams and waking. In this recent one, I struggled to free myself from within a room with walls of the same mosaic pattern. Their texture though, was membranous, and they bent to the pressure of my hand. Afraid that I would suffocate, I picked and prised at one raised corner of the pattern and peeled away a diamond-shaped flap that I realised, with horror, was skin.

“Can you believe that sleep?” Madeleine’s voice broke my thoughts.

I rolled to face her, and we smiled with peaceful satisfaction.

“I’d like to go back into Kos Town and have a look at it in the clear light of day. What do you think?” I asked.

“Sounds good to me.” Madeleine stretched and leapt from the bed with a return of her typical energy. “What did that hoverfly of a woman say about the hot water?”

“Something about the switch in there.” I nodded towards the wardrobe facing us.

With 30 minutes and two cold showers behind us, we set off for Kos Town.

Outside our unit, we took in the exterior of the complex that had flashed by us in the dark. Like others, it was finished in a brilliant whitewash – hard on the eyes in those places where the midmorning sun reflected. Though we couldn’t see any other tenants, there were signs of their lives – colourful beach towels over balcony rails, shampoo bottles just visible through opaque bathroom windows. At the front, the large swimming pool would have looked inviting if it wasn’t for the tiny whitecaps that were forming in the strong breeze that was blowing up the hill toward us.

The main road was about 100 metres down the drive, and, on its other side, the sea was just visible through the roadside trees. It wasn’t the vivid blue I had expected but looked churned and dirty in the wind.

“Are they really gum trees?” I pointed ahead.

“Yes! But here?” Madeleine was disappointed.

* * *

When we reached the road, there was nothing that resembled a bus stop, but 200 metres to our left, in an open-air restaurant, a tall figure was moving between tables, setting up for lunchtime trade. As we approached, I leafed through my pocket dictionary, but before I could say a word the figure, a young man, called his hello.

We returned it.

“Hellooo Ossie!” he boomed again, “Gedayyy Maite!”

Bewildered, we introduced ourselves and he told us loudly, in fractured English, that his name was Alexander, that there was indeed a bus stop and that the bus was due any minute. We noted the menu for a later time, thanked him and headed back up the road.

“No whurrries, Ossie!” he called after us, “Come back for meal! Ask for Alexander… Alexander the Great.”

“No worries!” we called back, certain that we would eat there in the future.

CHAPTERSEVEN

On cue, the bus arrived full of young, tanned tourists of various nationalities. We jostled our way past long, sandalled legs and backpacks and took a seat at the rear.

“It seems we’re staying in the Psalidi area,” Madeleine looked up from the map in the guide, “Further on from us there are hot springs…” She stretched her legs in front of her and gave a soft, wistful groan.

“We’ll look into getting a car today,” I said, thinking that my own muscles would be grateful for the springs. I’d noticed a hire place not far from Alexander’s restaurant.

“We’ll check out Kos Town first though and drive back… home.” How strange the word sounded to me then. Our little unit would be “home” for the time being and the thought sat well. I looked at Madeleine who, it seemed, had also noted the significance. She gently elbowed me and smiled.

“We’re here,” I said, returning her smile. “We made it.”

* * *

Through the grimy windows of the bus, we took in the flat salt marshes as they rolled to the sea to our right and the brown and rocky hills to our left. Along the way, hotels clustered to take advantage of the sea. On a stony beach close to the road, empty deck chairs waited for hotel patrons. Further on, the roadside thickened with restaurants situated among plane trees, palms and purple bougainvillea. To the right, as we approached the fort, I saw the park bench where we had been “abducted” in the early hours of the morning. Across the water to Turkey, Bodrum was a white smear that spread from its harbour to the bare brown shoulders of its hills.

I sought the sickle moon, wanting it to be our talisman for the journey. It was still faintly visible, its two points facing west. A waxing moon, I thought, an age-old sign of fertility and propitious times. But that was in the southern hemisphere, I remembered. In the north, this was a waning moon.

The road veered between the fort on our right and large Venetian-styled buildings on our left. Already, at 11 o’clock, the pavements and the bridge above us that joined the town to the fort were filling with tourists and locals. The driver pulled the bus into a bend in front of the large open-air square that was packed with rattan tables and chairs. We had passed it all in the dark, but it had been hidden from us by our fear and exhaustion.

As we stepped on to the footpath, we were enveloped by air thick with the smell of diesel, fish, char-grilled octopus and roasted coffee beans. There were sounds of laughter, good-humoured shouting, the high-pitched whine of motor-scooters, fishermen yelling to each other and the thud of moored boats nudging. Sunlight refracted through olive oil and diesel vapour reflected off concrete pavements, whitewashed walls and harbour water. The town glowed in that light.

Holding each other’s arms and tucking in our rears as a scooter whipped behind us, we crossed the road to the harbour. Boats of all shapes and sizes jostled at its edge. The large, modern ones looked arrogantly down their long prows at the working boats below. In various stages of disrepair, these little locals rocked enthusiastically, nudging each other like the local boys when long-legged girls ambled by the quay.

For the next half hour, we skirted the harbour taking in the town, exchanged some dollars for Euros and mentally noted other practical needs – laundromats, pharmacies, general stores and smaller cafés with cheaper prices. But on our first day we resolved to eat and spend large. We crossed back to the main square and were steered by a restaurant hawker to an outdoor table.

* * *

In only half an hour I had devoured a vegetable moussaka as though it was my last meal and relaxed into the high-backed rattan armchair. Madeleine was still savouring grilled sardines in tomato and caper sauce. She was relaxed and I realised how much the adventurer in her needed to be appeased. Already my sister was fusing with the locals.

People frequently commented on our similarity, but I could only see our physical differences. Madeleine’s olive skin compared to my fairer version was already deepening as we sat in the spring sun. Her large, dark-brown eyes betrayed vulnerability, despite her bursts of extroverted enthusiasm. I wondered if my own unremarkable blue-grey eyes had glazed to form another barrier to the world. We were of similar height, but Madeleine was more solid from years of physical work. At 35, she still worked as hard as the young apprentices she trained in horticulture and landscaping.

I closed my eyes enjoying the sun’s warmth on my face and arms and let the sounds of the restaurant filter through – the clink of glasses meeting in salute or being swept together by a busy waiter; conversations blending into an indistinguishable murmur, punctuated now and then by a bellowing laugh.

I opened my eyes and took in the other patrons. At one table, four men of stocky build and weighty gold jewellery were in animated conversation, gesticulating to each other. If they hadn’t been laughing, I would have thought they were arguing. At another table, a raven-haired man in his thirties was entertaining two attractive Nordic-looking girls. The dark curls of his hair framed a sharp, narrow face. When serious, or listening intently, he tilted his head back and looked down his impressively long, aquiline nose. From my side view, this made him look arrogant and hard, but when he smiled or laughed, his face transformed into something to behold – like a euphoric drug, an aphrodisiac. Certainly, the body language of the girls with him suggested that they thought so, and I too found it hard to take my eyes off him.

He was a charmer and everything about him exuded confidence and sensuality. His movements were languid and graceful – the crossing of his long legs, the stretching and folding of his arms and elegant hands behind his head.

“Dee… Dana! Ooohh, my God, he’s gorgeous!” Madeleine’s eyes had followed mine.

At this point in our lives, my sister and I were both single. She searched for the soulmate who eluded her, but I’d never believed in the concept until I met Julian. I quickly diverted the thought.

“Greek, do you think?”

Madeleine considered him “Possibly. He could be Spanish or Italian… let’s ask him.”

In the middle of my grimace, he rose and cupped and kissed the face of each of the girls in turn. He left them twittering at the table and headed in our direction with a slight limp. Holding my breath, I gave my sister a light kick – a warning not to open her mouth.

“Ciao, signorine.”

As he passed, he granted us a dazzling smile.

“Ciao,” we said in unison, and far too loudly.

* * *

We paid for our meal and wandered deeper into the square and its tributary lanes filled with souvenir shops that sold small, white statues and busts of Hippocrates, scrolls of the Oath and other selected sayings. The merchandising was overwhelming, and I felt foolish at my romantic ideas about visiting his homeland.

Madeleine placed her hand on my back. “Let’s find his tree.” She perused the guidebook in her other hand looking for the route to the famous icon.

“This way.” She nodded to our left.

We negotiated only a few lanes uphill until we came to Platanou Square, a small but beautiful park-like setting with plane trees and palms, cobbled paths, remnants of ancient buildings and beautiful restaurants with terraces draped in bougainvillea. Here, the air was still and though the terraces were filled with diners, they seemed hushed and muted in this space.

It wasn’t difficult to find the famous plane tree, though it was fenced off and supported by scaffolding. Undoubtedly it was old – though not as old as the Koans would have tourists believe. The thought was sobering, and I wondered if there was anything authentic left on this island.

I sat on the edge of the low wall that surrounded it and contemplated the peace of the square, taking in the ancient Turkish sarcophagus a few metres away, and the bridge to the main entrance to the fort—the Castle of the Knights.

“I’m going for a stroll.” Madeleine headed toward the bridge, leaving me to daydream.

Whether Hippocrates had taught under this plane tree or not, the square had seen much of the life of ancient Kos Town. Most certainly he would have walked here, perhaps deep in a thought or conversation that would ultimately change the practice of Western medicine. I turned to face the tree, picturing him walking with his students. I waited for a feeling – that I would find an answer to a need I could not yet identify. Was I right to come here? There was a rustle in the leaves as I mentally posed my question, but nothing more.

On the bridge, I joined Madeleine, who was studying the sign on the double gates into the castle.

“Too late today – we’re locked out,” she said.

“Yes,” I said, “I could believe that.”

* * *

An hour later, and with basic supplies, we walked back along the avenue to a car-hire outlet I had seen from the bus. We left in a Fiat – freedom in canary yellow.

When we arrived at our complex in the late afternoon, we wondered if the signs of life we had seen in the morning were just props arranged by our hoverfly and husband. Once inside, I could see, on the neighbouring balcony rail, two pairs of feminine feet that flexed expressively with the animated conversation of their owners.

We ate a light tea of Greek salad and local wine on our own balcony and soaked in the atmosphere that was free of wind and sound. In the dusk, the hills turned from brown to grey and, as night set in, the lights in the condominiums were matched with stars. Lulled by the peace and our full stomachs, we reviewed our journey so far and decided that, perhaps, it was not a mistake to come after all.

As the evening turned cooler, I left Madeleine to contemplate the view and went inside. I took out the collected material on Hippocrates and, for the next hour, searched through the books on the bed looking for something that would resonate to my core or shake the foundation from under me.

Under that stark, naked bulb of my Kos bedroom, I gained a better appreciation than I had ever had of his influence on Western medicine, that he had taken its practice out of the hands of the priests who loaded their patients with guilt and brought rational understanding to the cause and treatment of many diseases. I understood more deeply that his influence had extended through the generations of medical training, and had been fundamental to my own, but there was a new recognition in me, that something was missing. I felt dry.

Madeleine tiptoed in and, without speaking, sank into bed. After another fruitless hour, accompanied by my sister’s soft snoring, I thought that perhaps Hippocrates could not be truly known through the written word, but would need to be experienced in his homeland.

CHAPTEREIGHT

The wind that had whipped up the sea the day before had eased, and the Aegean was its trademark blue. As we began our ascent, the view was stunning and the cape, where the island’s mountain chain came to a rugged end, had the look of a racked and life-beaten soul. On a small plateau, before the descent to the hot springs of Thermes, wild goats grazed while their kids played in the stones and tufts of the coastal grasses.

I pulled into a car park to join two other hire cars. From the top of the worn and precarious staircase we could see four women lying in the shallows where hot water seeped through small vents near the shore. We descended, gripping at the rusted and brittle rail. The sheer cliff face opposite us loomed over the stony beach. Here, the seep of hot water at the cliff’s base reminded me of the awesome force that lay beneath, like the tic of a madman.

If my sister was threatened by this brutal beauty, she didn’t appear so. No sooner had we chosen our place among the pebbles than she was stripping to her bathers and tottering barefoot to the vaporising shallows. She had already taken up position with the other women when I reached the water that immediately fizzed around my feet.

The prone, silent women unnerved me, and when they opened their eyes to take me in, I self-consciously lowered myself into the water’s warmth and lay on my back next to Madeleine.

It was a surreal moment, lying in silence in a type of sisterhood with the women, and I wondered if we were re-enacting a similar scene two-and-a-half thousand years earlier. As I lay in the sulphurous balm, I took in those boulders that lay at the cliff’s feet and looked for their origins on the face, tracking my eyes up and up to the towering summit and to the impossibly blue sky. I closed my eyes and felt the warmth seeping into my limbs, the sulphur into my nose and I imagined myself slowly disassembling in this stew, returning my molecules to the whole.

I felt weightless, borderless. Through my hooded lids, I took in again the summit of the cliff and saw a movement among the straggling vegetation. A small rock dislodged and trickled to a shelf below. When I looked up again, a mountain goat stood looking out to sea.

Madeleine continued to meditate in her bath, but two of the other women began to murmur softly to each other in German. I closed my eyes again and soaked up the heat, the peace and the sound of them, and thought of my childhood holidays spent on the beaches of one of Melbourne’s own peninsulas.

I thought of the hours spent swimming in the bay during the seemingly endless summer days of my youth and how, exhausted from swimming, I would throw myself on to the sand and listen to the sounds of the beach – the gulls fighting each other over the scraps from someone’s fishing bucket; of other children playing in the water’s safe aqua zone, and the drumming of the hulls of hire boats anchored just offshore. I remembered that freedom, the complete happiness of it. And I felt it here too, in the hot springs of a foreign island.

* * *

For the rest of that day, our muscles revived and feeling a luxurious calm, we toured the length of the island, marvelling at its history, in awe of the olive trees that resembled the animated trees of fantasy. Cultivated in groves hundreds of years before and now growing wild, they would have been witness to generations of change. When we returned at sunset, we decided to try out our local restaurant. Alexander greeted us with the same effusive enthusiasm as he had the previous day.

“Geddayyyy Ossies!”

Madeleine was intrigued. “Alexander, how do you know we’re Australian?”

He looked at her in mock bewilderment.

“How you talk! Must be how you look!” he said, waving his arms up and down. He guided us to an outdoor table.

“Do we really sound like that?” Madeleine persisted.

“No whurrreees,” Alexander laughed. “When I was in Melborrrne,” he confided, “everybody,” he added, moving his arms like windmills to make his point, “speak same.”

“You’ve been to Melbourne?” I said, the world feeling smaller to me all the time.

“Of course! My aunteee, uncle, my cousins all live there. I stay for six month… for geology.”

“Geology?”

“Alexander is not just a fabulous waiter,” he boasted. “I also nearly a geologist.”

I stored this information away for the moment thinking of the tiny stone stored in my room.

“Why do you come all the way to Kos?”

Between us Madeleine and I told him, in our broken version of English that we had come to learn about Hippocrates.

“Ahhhh, great man,” Alexander said dreamily,” but, for me, not so great as Asklepios.”

I knew that Asklepios had been worshipped by Hippocrates, who honoured the god in the first line of his Oath, and that he was included in the recounting of Hippocrates’ dream that I had read on the plane. I thought that I knew him, too, from another source, but couldn’t think of it then.

“He was greatest healer,” Alexander continued, “long, long time. Even before great battle of Troy.” A family arrived and he apologised as he left to attend to them.

“Interesting,” Madeleine said, spreading hummus on thick slices of bread.

“Yes.” Asklepios, I resolved, would have my attention.

Back in the room, while Madeleine introduced herself to the “feet” next door, I resumed my research, from a different angle. The books in my possession made only fleeting reference to Asklepios and there seemed to be some confusion whether he had been a man or a god. His origins, though, were in Thessaly and there was a temple dedicated to him there, in Epidaurus and in Kos at the site known as the Asklepion. Although Asklepios had been worshipped on Kos, and that Hippocrates himself was an Asklepiad – a supposed descendant – the younger physician was the main hero of this island. The next day, I decided, I would go to the Asklepion.

CHAPTERNINE

“I need some retail therapy,” my sister announced the next morning. “From what I’ve read, Bodrum’s the place for it, and only 30 minutes away by ferry.”

The morning sky held the promise of a sunny day and I told her of my plans to visit the Asklepion. “Have a rest,” she said, “and don’t overdo it.”

After dropping Madeleine off at the quay, I wound my way through the streets of Kos Town, through the Turkish Platani area with its traditional tavernas, complete with blue-and-white check tablecloths and vine-strewn pergolas, to the Asklepion, four kilometres out of town. As I pulled into the car park, my heart sank at the sight of two large tourist buses already there. I bought a ticket and map and followed the signed path that opened suddenly on to a clearing in the hillside.

Standing at its base, I took in the three terraced levels of the Asklepion that unrolled ahead of me to the top of the hill. From where I stood, I could see that each level was littered with ruins of temples. Some pillars were still standing, but most were lying where they had fallen centuries before. The sightseers from the buses were milling over the levels in a fine stream up the central staircases, or in small groups huddled around a tour guide. And yet, there was a pervading sense of quiet.

On the first terrace, the Romans had left their trademark – the remnants of a large bathing house. In recesses of a retaining wall, headless statues stood with authority. In one small grotto, a maidenhair fern had found its niche beneath the glare of a lion’s head where a mineral rich spring spewed from its mouth. I climbed the 20 steps to the second terrace. To my left stood colonnades – the remnants of the temple to Apollo – to my right, the altar to Asklepios. It consisted merely of a large slab of marble supported by thick rectangular stones. I stood before the altar and ran my hand over it, wondering what had been offered there more than 2,500 years earlier. I closed my eyes for a moment and was startled by the pungent and unpleasant smell of fish.

For two hours, I wandered the terraces, consulting my paper guide and tagging tour groups to catch some more detailed accounts in my rudimentary understanding of German and French. Every now and then thick, dark clouds would cause a light and shade strobing that accentuated the dramatic feel of the place.

On the large retaining wall of the third terrace, I sat like a child with my legs dangling over the edge as I took in the spectacular view of Kos Town, the sea and the coast of Asia Minor. Out there, the world, including my sister no doubt, moved at a frenetic pace, but this place was a peaceful core. Everyone seemed to sense it, talking in muted tones, or just sitting alone or with others in silence. In the cypress grove that buffered the two worlds, I read, birth and death had been forbidden.

Beneath my dangling feet were the remnants of the abaton – the rooms where the sick would come to sleep. It was here, in their dreams, that Asklepios would appear and advise them of a cure. I marvelled at such simple faith, but thought, too, of the tragic repercussions when that faith was misplaced. I had left elements of my life behind in Melbourne, but Bonnie travelled with me. I wondered where and how I was to heal.

I was drawn now to the rooms beneath me and descended the stairs to sit alone among the ruins almost hidden in the grass. The dark clouds were colluding and forming a thick, menacing ceiling. Where I sat on the remnants of a stone wall, I ran my finger into its nicks and recesses, imagining an ancient hand fashioning it in honour of the god. This site was built after the death of Hippocrates, but it was Asklepios and Apollo who were worshipped here.

At my feet, tiny wildflowers grew – purple with yellow centres. The longer I looked at them the larger they appeared until I felt myself drawn to them. A bee rested delicately on stamens, and I became mesmerised by the humming of its wings. I wasn’t aware of falling asleep, only the weight of my head, a heaviness of my limbs and a sense of stupor covering my scattering thoughts in fur.

I remember blurred images – imperfect apples, olives and wheat placed with love on a marble table in front of me; fish that now seemed pleasant and whole and organic, and shells fashioned into necklaces. I saw the sick in their beds waiting with trust for their cure. I felt their fear, their maladies. I reached forward to one and touched her barren womb and tracked my way to her troubled heart. In her sleep, she wept. For another I pricked his skin and tongue with nettle to clean the black from his blood. And then I saw myself lie down, to dream of a cure for my troubled soul. The heavens roared and a spear of light jagged its way across the sky to find me.

I must have yelled. When I opened my eyes, a couple was watching me warily. I feigned indifference and stood and stretched. Though the sky was becoming dark there was only a very distant rumble of thunder, but I wasted no time in returning to the safety of the little canary.

* * *

“You look awful.”

“Thanks for that,” I said, knowing well that Madeleine was right. “How was your day?”

There was a heightened sparkle in my sister’s eyes that sounded a warning bell in me.

“So, who is he?” I said, not taking her by surprise at all.