0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

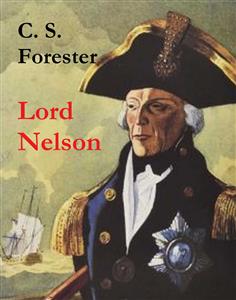

The celebrated author of the Hornblower series presents the biography of Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, the victor of the naval battle of Trafalgar.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Lord Nelson

by C. S. Forester

First published in 1929

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Lord Nelson

★

a biography

by C. S. Forester

Contents

I.

THE LETTERS AND DESPATCHES

7

II.

THE BEGINNING

16

III.

MODEST STILLNESS

34

IV.

THE MARRIAGE

43

V.

THE ENEMY

48

VI.

THE PATH OF GLORY

54

VII.

“AGAMEMNON”

65

VIII.

ST. VINCENT AND SANTA CRUZ

80

IX.

THE NILE

90

X.

NAPLES

106

XI.

PALERMO

115

XII.

TWO MONTHS IN ENGLAND

129

XIII.

THE BALTIC

134

XIV.

THE CHANNEL AND MERTON

146

XV.

THE BLOCKADE

154

XVI.

THE PURSUIT

168

XVII.

TRAFALGAR

176

CHAPTER ITHE LETTERS AND DESPATCHES

HE has left behind him more than the memory and evidence of his achievements. There is also the large mass of his letters and despatches, gathered for the most part into a single series of volumes, with a large remainder to be found and read by those who can make the opportunity for themselves. In this respect as a subject of biography he resembles Napoleon, whose correspondence is readily available for examination, but in the most important other respect he is not comparable—in the sense of an object of study.

Contemporary studies of Nelson are woefully few. About Napoleon, for example, there can be no doubt as to his ability in the minor practice of his profession—innumerable witnesses can be called to show that he was as good a regimental officer as he was a general-in-chief; but in the case of Nelson very good evidence can be produced to show either that as a seaman he was excellent or only fair to middling. Good contemporary judges have said both the one and the other; and, confronted by such a direct opposition of opinion, the modern biographer seeks further written evidence, generally in vain. He is left to make what deductions are possible from the Letters.

Yet, although the Letters are the main source of information, they are a very satisfactory source. Study of them calls up instant pictures of the writer, of his momentary state of mind and of the permanent trend of his thoughts. His anxieties, both public and private, his pleasures and his hopes, can all be discerned. He becomes a much more human, living, sympathetic being than ever Napoleon can, perhaps because he was not given to intrigue or to the disguising of his thoughts to those in his confidence. Even Napoleon’s love-letters, written before thirty, show us less of Napoleon than Nelson’s after forty show of Nelson. The personal Nelson is always observable; that may be the reason why he is so delightful a subject to read about or to write about in comparison with, say, Wellington, whose brutally impersonal correspondence is a mine of military information but monotonous reading to the student of human nature. This may, perhaps, stand as the excuse for the publication of a biography of a seaman by a professional novelist whose work consists in the study much more of human beings than of maritime affairs; it seems a sound enough defence.

Very nearly everything we know of Shakespeare, to take another example, is drawn and deduced from his work. The minute amount of other evidence consists of meagre scraps—his will, obscure references in parish records, doubtful tradition. It has become usual to conclude that we can draw a mental picture of Shakespeare after an examination of his work, which appears to be an exceedingly dangerous assumption, the more dangerous, perhaps, because of the impossibility of its contradiction. Yet no one can doubt that we should know much more about Shakespeare if only he had left some traces of his private life behind, in addition to that allusion to his second-best bed. Nelson’s “Hamlet” is the Nile, his “Lear” is Trafalgar, his “Twelfth Night” is Copenhagen, his “Othello” is his last Mediterranean campaign, his “Henry VIII” is St. Vincent; but we have more than his works by which to know him.

We can read his own very acute estimate of his own professional worth, and his equally acute estimate of that of others, tinged, but not falsified, by his odd tendency to the hero-worship of those of his superiors in rank who are of proved merit, and of the youngsters of promise; tinged also by his petulant prejudice against the men of average talent with whom he has been at disagreement for some reason or other. We can read of his untiring patience and his extreme attention to details of organization—for that we need only draw attention to his elaborate arrangements for convoy during the last period of his Mediterranean command. We can read of his uneasiness under authority—uneasiness, not disloyalty—at the same time as we can study his open-handed delegation of authority to trustworthy subordinates and his right grip upon juniors with a tendency towards shiftiness. We can follow his own opinion of his health, which improves and declines in inverse ratio with the prospect of action. We can read his oddly flavoured letters to his wife, where “esteem” usually takes the place of “love,” and where self-deceit leads him into tactless displays of a lack of feeling extraordinary in one so sensitive. We can study his progressive idealization of Lady Hamilton, idealization expressed in terms by high passion yet mingled with others of a jocose coarseness which leave one wondering. We can follow the gradual growth of his taste for applause and his simple delight in the admiration of others.

The Letters present a complex human problem to which one can turn again and again with increasing interest. Their style is consistent and attractively naïve. There is little trace of schooling (Nelson was only twelve when he left school) and the grammar is very frequently faulty—although in this case allowance must be made for the fact that many of the letters, clearly, were dictated, and hurriedly at that. Compared with Collingwood’s or Cornwallis’s despatches they are very inferior in this respect. They betray no sign of wide reading or of literary taste—the only quotation they contain which comes to mind is from “Henry V,” and that is misquoted—“But if it be a sin to covet glory.” Much more surprising is the fact that they contain hardly any hint of passion for his profession or for the sea. Nelson, who is so unreserved in his expression of his sentiment, never once baldly declares that he is glad to be a naval officer, and the reader cannot help harbouring the suspicion that his affection for the sea was never more than lukewarm, and even changed latterly into plain dislike; possibly because of his sea-sickness, or because of the difficulty, after the loss of his arm, of his boarding and quitting ships, and because the sea lay between him and the object of his beglamoured affection. The tenor of many of his later letters, indeed, is of his wish to retire and leave the sea, and settle down in some quiet corner of the country, or in Bronté, for that matter, with his loved Emma—an experiment which it is probably just as well he never attempted to carry out.

Throughout the correspondence there runs a strongly religious sentiment, of whose sincerity we can have no doubt. As the son of one clergyman and brother of another, Nelson’s early thoughts must have been given a religious turn, and he seems to have remained quite untouched by any of the fashionable fads of irreligion. When he declared that Almighty God had granted victory to His Majesty’s fleet, he meant just what he said, for he often wrote much the same sort of thing to Lady Hamilton, which no one would expect him to do if he had the least shred of doubt. With all that, nevertheless, he never seemed to think there was anything sinful in his treatment of his wife or in his relations with Lady Hamilton—religious feeling and passionate desire between them worked their not unusual miracle of sanctifying the satisfaction of an intense longing, the intensity itself being the apparent grounds of the sanctification.

Along with this devout belief in God runs an equally devout belief in the institution of monarchy. Republicans are as damnable as atheists, and the more so as it seemed a usual occurrence for the former to be the latter as well. The man who did not believe in kings was the wrong kind of man and should not be allowed to exist; it is impossible to doubt that this is a very close approximation to Nelson’s actual sentiment. The British system of government was the best the world could show, and, moreover, was so nearly perfect that to want to change it was a horrible crime. Even so shrewd a judge of men as Nelson had his judgment a little clouded when dealing with kings; his opinion of the King and Queen of Naples was a good deal higher than that held by the majority of students nowadays. The wretched Paul of Russia, even, rises in his eyes up to the standard of common humanity at least. His personal devotion to hard-working, conscientious, honest King George is more easy to understand.

It is only when the strongest of all human passions is at work that he is able to visualize Royalty without its aura, and then he writes about the Prince of Wales (George IV to be), whom he suspects of attempts to seduce Lady Hamilton, with an hysterical emphasis transcending even that employed about Frenchmen. For he had a most poisonous hatred of Frenchmen and all things French. It is not so hard to understand, seeing that for the last dozen years of his life Frenchmen were to be detested as Republicans and Atheists as well as the enemies of his country. His few months’ stay in France during his period of unemployment seems not at all to have tempered this ungovernable aversion. Naturally his ignorance of French literature and the fact that his acquaintance with French people was restricted to members of the official and military classes did not help to remedy this state of affairs.

Indeed, there can be no denying that he was a man of very limited range of interests, which makes the extent of his knowledge of human nature all the more surprising. He had little appreciation of art, although he extended a good-humoured tolerance to Sir William Hamilton’s twin passions for collecting and for music—in one famous letter he lumps together fiddlers, poets, whores and scoundrels in a single scathing denunciation. Yet with all that he could form a very clear estimate of public opinion, and he knew what would be likely to catch the interest of the mass of human nature, as witness not only the Trafalgar signal, but also the now-hackneyed account of his career which he wrote for the “Naval Chronicle.” That account bears the stamp of undoubted journalistic talent; the manner in which unimportant but interesting details are brought in to illustrate important developments (his account of St. Vincent gives another vivid example) and the self-confident style are sound journalism. It was only when his judgment was clouded by his unblessed passion for Lady Hamilton that it became faulty in this respect. He was unable to estimate the effect of his attachment (and of his treatment of his wife) on public opinion, and he was puzzled by the attitude assumed by the Court towards Lady Hamilton—later in this book there will have to be decided the debatable point as to whether this clouding of his judgment did not extend to military and political affairs as well.

In one respect at least the study of the Letters is not so prolific in reward. That is in the effect Nelson had upon others. We catch glimpses of it, but we have to go to other authorities to appreciate fully his power of inspiring others, which was so largely responsible for his success. We can approach the matter indirectly; thus, study of his memoranda for battle leaves one quite doubtful as to whether orders of this sort would bring the stupendous results of Trafalgar or the Nile. The verbal explanations which ranked far higher in importance than the written memoranda counted for something too, but nobody can doubt that more important than either was the spirit of loyalty and emulation which he was successful in calling up—that threadbare declaration of Napoleon’s, that in war it is not men that count but a man, is more applicable in the case of Nelson’s campaigns than in any other example in modern military history. A fleet commanded by Nelson was equivalent to a fleet manned by Nelsons, and once that is said there is little room left for further labouring of the point.

For the bare wording of his orders gives a faint feeling of something missed; the Admirals and Captains who read those orders could supply that something out of their personal experience through actual contact with the magic personality, but we who live four generations later can only make good the deficiency with an effort. Not that the orders are equivocal or liable to misinterpretation (and we, of a later age, of personal experience of military orders ourselves, know how much that means), but they lack the literal clarity of Wellington’s orders (perhaps Eton and the Military College, Angers, are responsible for that well-directed prose) and the exacting vigour of Napoleon’s early orders. It is just possible that a fuller classical education or a modern course in essay-writing would have led to the casting of those orders in terms which would have clarified their significance to us. But it is far more likely that their lack of instant appeal is a defect only due to his qualities of leadership.

Over one other matter discussed in the correspondence can the reader hesitate in doubt, and that is Nelson’s proposals to employ a land force against the rear of a hostile army. It seems likely that it was fortunate that none of the Austrian or Piedmontese generals fell in with his suggestions during the Riviera campaign, and doubly fortunate that no English troops were at Nelson’s disposition. Nelson seems to have formed a faulty estimate of what could and what could not be done with troops operating on land, and for any tangible result to have ensued from the plans he submitted enormous and unjustifiable risks would have had to be run. His plans match Napoleon’s clever landsman’s orders to the French fleet, and compared very unfavourably with Wellington’s employment of the naval arm, for Wellington never asked sea power for more than sea power could reasonably be expected to perform. In this respect again Nelson’s deficiency (if deficiency is admitted) must be attributed to his lack of general education in the wider sense.

Nowhere in the bulky volumes can there be found proof of a militaristic turn of mind. On occasions he thoroughly approves of the execution of mutineers and of strong measures to be taken against bad characters, but he never admires a fighting service just because it is a fighting service, nor has he a word to favour of war for war’s sake. He is glad of peace when there is nothing to be gained by war, and although war brings him activity and employment, he finds in that no reason to rejoice at its coming. He will even hope for peace because he sees no object in the continuance of war, and not even the scoffer can advance the argument of a doubt as to his motives, because the sentiment occurs in a letter written before he made the acquaintance of Lady Hamilton.

His own ends, indeed, are the subject of few of the letters, and these are oddly contradictory. He could write flattering, even fulsome, letters of admiration to his superiors in the service, but no one reading them, even without knowledge of the circumstances in which they were written, could possibly think they were intended to curry favour for the writer. They display not so much indifference as a fatalist resignation regarding his future. Yet at the same time they show him to be most decidedly touchy regarding his present fame; if he has deserved praise he is annoyed when praise is not meted out to him, and he is annoyed, too, if the public acknowledgments of service in the way of titles of honour do not amount to what he has expected. But still, side by side with his complaints in this matter, go more fervent complaints still on behalf of his subordinates: good service to Nelson meant a loyal and untiring representation of that good service to headquarters.

He is rather pleased with his dukedom and peerage and diamond orders, although he is not above using the holding of honorary distinctions (by men he disliked) as the basis of a sneer—Captain Sydney Smith is “the Swedish Knight,” Admiral Orde is “the Baronet”—just as Wellington’s generals usually alluded to their awesome but unloved leader as “the Peer.” He saw the ridiculous side of these distinctions at the same time as they flattered his childish vanity; perhaps the son of a poor parsonage could hardly help on occasions but feel there was something peculiarly special about titled gentry, and he was practical enough, too, to appreciate the spur the honours bestowed upon him might be to the others in the service.

One more constant impression received while reading the Letters is that of a vast potential energy awaiting employment. Even in the dark, unhappy period of his subordination to Keith in the Mediterranean, when his letters repeatedly bewail his ill health and his dissatisfaction with his situation, there is obviously behind the letters a possible source of energy only waiting to be tapped. Keith, poor man, honest, courteous, and even tactful though he was, was not the man to tap it, nor was Emma Hamilton the woman to direct it into its best channel. This was the worst time; during other periods no one can fail to be intensely impressed by the force and vigour of the personality behind the Letters, by the feeling that the writer would never, never leave undone the things that ought to be done, and, for that matter, would never cease from seeking to do things which it would occur to few as necessary to be done.

The general run of biography, in fact, tends to give the average reader a warped idea of humanity, because biography necessarily gives most of its attention to men who have done things. The biography of a very ordinary man might be tame reading, but it would be instructive when employed for purposes of comparison. Byng’s despatches, for instance, written during the Minorcan campaign, show a man encountering difficulties at every turn, and simply without the force of character or the ingenuity to override them. In his own opinion Byng was innocent of everything charged expressly or by implication against him—undoubted facts had been too much for him, and to Byng that was both reason and excuse for his actions. A Byng cannot imagine a Nelson overcoming the difficulties, circumnavigating the facts, which have defeated him, for if he could he would cease to be a Byng and become a Nelson. To shoot a man because he has not by his own personal ability risen superior to circumstances may not be justice, as Voltaire pointed out, but at least it keeps his memory before the eye of the public as a standard of comparison with those men whose talents—ingenuity, energy, imagination, experience, perseverance or anything else desirable—have enabled them to do so. In reading the chapters which follow it is necessary not merely to realize what Nelson did, but also what he might have left undone. That is the measure of greatness.

CHAPTER IITHE BEGINNING

THE meagre scraps of information—hearsay evidence, much of it—have been gathered together time and again; Southey made much of them in his mellifluous prose. They tell us almost nothing which is worth knowing. We cannot form a picture of the young Nelson with one half of the clarity of that of the young Napoleon, because the materials are wanting. There was no Bourrienne at Nelson’s side to give us facts and descriptions (even erroneous ones) which might be used to fill the gap. The few anecdotes which we have could be told about almost any boy, and partly for that reason will not be told here. One noticeable fact is that the only motive which has been put forward for Nelson’s desiring to go to sea is the wish to relieve his father of the burden of supporting him—hardly the most significant beginning of a career. We can trace no vocation such as Napoleon undoubtedly felt towards a military life.

However it was, this twelve-year-old son of a Norfolk parsonage took advantage of the fortunate possession of an uncle who was a Captain in the Royal Navy to be entered into the service at a time of expansion during an alarm of war. Captain Suckling was a man of some distinction in his profession, who later was to hold appointments of very considerable influence; at the moment it sufficed that, as Captain, he had a certain amount of patronage, being able to appoint on board his ship one or two children as “captain’s servants” and midshipmen. The alarm of war passed, and Captain Suckling was transferred to the “Triumph” guardship in the Medway; his nephew nominally went with him. Yet while he was borne upon the books of the “Triumph” he was nevertheless sent to the West Indies as a seaman in a merchant vessel (he was not yet thirteen, remember) to learn as much of his trade as would be possible in the circumstances—more, apparently, than he would learn in a Medway guardship—and on his return he was employed in small boat work attendant upon the “Triumph,” which was the best method possible in the circumstances of habituating him to command and responsibility; the method is employed to this day in the navies of the world for the training of young officers. Constant work amid the shoals and currents of the Thames estuary did something more: it instilled that self-confidence amid this kind of peril which was to find its expression at moments of vital importance in English history at the Nile and at Copenhagen.

His next employment seems to have been obtained (unless Captain Suckling’s influence had more to do with it than Nelson knew or admitted in his own biographical sketch) solely by that influence of his own personality, which was to become so powerful a means to advancement and success. An expedition into North Polar regions was being fitted out; the decision had been made that no boys were to accompany it, but Nelson, who was personally acquainted with Captain Lutwidge of the “Carcass” (a bomb-vessel which was one of the two ships to sail), succeeded in persuading him to include him among the exceptions. The expedition sailed, did nothing in particular, and came back again with not much knowledge gained; its one contribution to history is the well-worn anecdote which displays Nelson on the ice planning an attack on a polar bear with the butt end of his musket—an anecdote which is of no use to us, because, although it may illustrate extreme personal bravery, it hardly gives proof of the various other qualities which Nelson possessed.

Then on his return he found again how useful an uncle may be, for only a fortnight passed before he was employed again, this time on the corvette “Seahorse,” in which he sailed forthwith to East Indian waters. His period of pupation as a “captain’s servant” drew to an end at last on this voyage, and he became a full midshipman, presumably holding His Majesty’s warrant, and on the way to exchanging it for His Majesty’s commission. But after two years he was invalided home to England, a very sick man (or boy—he was just eighteen) with, implanted in him, apparently, the beginning of that weakness of constitution which was to go with him through life. All the same, there was a silver lining to the cloud, for eighteen months before his return his invaluable uncle had been appointed Comptroller of the Navy, and in consequence held a position of much patronage and more influence, the first proof of which to Nelson was his appointment as acting lieutenant on the “Worcester,” 64. Six months’ service on the trade route to the Mediterranean followed, and then came his examination as lieutenant, which he passed well despite the fact that his uncle, who was on the board, concealed the relationship between them from his colleagues—proof enough, seemingly, that at this stage at least his seamanship was not so poor as to merit Codrington’s description of him as “no seaman.” Then Suckling did Nelson his last great service, by giving him his immediate appointment to “Lowestoft,” 32, about to sail to the Jamaica station, where fever and other incidentals of service were likely either to cut a career short or give it a decided impetus by rapid promotion.

And, moreover, there was likelihood of promotion. The discontent of the American colonies had, some time before, expanded into active revolt. British armies were moving ponderously about the rebel states, or being transferred hither and thither by sea; even sea power could not multiply the scanty British forces sufficiently to enable them to hold down the whole huge area which was in rebellion. Already American privateers had made their appearance, bearing letters of marque and reprisals, and their activity already foretold the time, close at hand, when the linen ships from Belfast to Liverpool would need convoy in the Irish Sea itself. Already French sympathy (or not so much sympathy with America as antagonism to England) had displayed itself in the shape of liberal treatment of privateers and the private despatch of succours. To pin down the privateers and to intercept the contraband called for a blockade of the whole American coast, and the vast number of ships necessary for that undertaking America was to learn to her cost when later she had to fight her own rebels. The demands of military convoy, of commerce protection, and of blockade meant an expanding navy, and an expanding navy meant at least that there would be no hindrance to promotion.

Sea power had come to the rescue of Quebec, and ensured Canada against invasion, had carried Howe from Boston to Halifax and back again to New York; it was sea power which would decide a protracted struggle one way or the other. A year before Nelson received his commission the Declaration of Independence made it certain that some at least of the rebels would fight it out to the bitter end, and Nelson had hardly crossed the Atlantic before Burgoyne started on his disastrous march to the Hudson. Lord George Germain neglected his duty, and the uninspired but painstaking efforts of King George III were nullified. Howe directed his own blow where it would do no harm; his victory on the Brandywine and his capture of Philadelphia could not save Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne from being hemmed in at Saratoga. The surrender of his six thousand British troops was a disaster worse than that of Kloster-Seven; to find its parallel in English history we must go back three and a half centuries to the relief of Orleans. The news resounded throughout Europe; it meant the redoubling of American effort, but, worse still, it meant the intervention of that European power whose influence was most to be dreaded. Now, if ever, were Lagos and Quiberon to be avenged.

The end of the Seven Years’ War had found the French Navy in the condition usual to it at the end of a prolonged struggle with England. Fleet actions and attrition had worn down its material, and continued blockade had ruined its personnel. The French mercantile marine had been driven from the seas. Only a few bold privateersmen had continued the struggle, and by their efforts had given French maritime tradition a character which was for generations later to mould French naval policy. But, if French Ministers and French Admirals were to hold faulty theories about the employment of sea power, the genius of one French Minister was at least able to supply a French navy capable of action, even were that navy to be misdirected. Choiseul’s tenure of power had been signalized by an extraordinary maritime development. The French Navy had been rebuilt. The loss of so many ships left room for the introduction of new designs, and, ship for ship, the French vessels which were built were superior to the English ones. The influence of the Court was brought into play to popularize the service among the indispensable nobility, with such good results that before long a Prince of the Blood Royal held a subordinate command in the fleet—which was more than Louis XIV himself effected, for in his reign a mere legitimatized prince only condescended to accept full command. To man the fleet a long service enlistment was instituted, and could be supplemented by an Inscription Maritime which would bring in a substantial though fleeting reinforcement. For the supply of officers the Naval College was revived—Colbert had begun it nearly a century before—so that cadets could receive professional training, to counterbalance the system by which budding English officers (Nelson among them be it remembered) were trained in the extensive English merchant service. In a young navy a naval school implies a school of naval thought, and in a navy without past traditions of victory a school of naval thought will generally carry with it original thinking. Numerically the French fleet was little smaller than the British; its officers had largely received uniform training; it had developed ideas of its own—phrases which in 1914 were just as applicable to the Imperial German Navy. It was unfortunate, however (from the French point of view), that the ideas which were developed were not such as led to decisive success, with the result that a crisis which on the face of it was far more serious than any in 1914 was passed through without serious damage to England.

France had never in all her history enjoyed the relief from strain which is brought by a victory at sea. Her immediate independence, thanks largely, of course, to her powerful army, had never turned on the destruction of hostile ships. She could not look back to a vital victory similar to that of the English over the Armada. The reduction of her insurgent Huguenots had been achieved in the face of superior British sea power by reason of her overwhelming land power, of the misdirection of British effort, and of particular circumstances. Her victory at Beachy Head had been barren of results through Louis XIV’s infirmity of purpose. Duquesne’s splendid victories over Spaniards and Dutch in the Mediterranean had brought small profit because little had been at stake. On the other hand, La Gallissonnière’s partial action with Byng had won the magnificent prize of Minorca, despite the fact that Byng was neither attacked nor pursued with determination. The destruction of ships, to the French naval mind, was ranked (was actually described, in fact, by French writers) as merely the destruction of ships. The consequent profits of such destruction seem, amazingly, to have escaped detection, and French ingenuity was devoted towards finding ends which sea power could attain while avoiding decisive action and losses—a search which was only not quite as barren of results as the contemporary endeavour to find the philosopher’s stone or to square the circle.

A tactical system, naturally, had to be developed to accord with this perverted strategy. One was evolved and brought to perfection, apparently more as the result of staff work than by test in action, but which nevertheless succeeded in baffling a whole generation of not too incapable British Admirals. It consisted, as is well known, in taking the leeward position in a fleet action, firing at the enemy’s spars in preference to his hulls, and, as soon as close action was imminent, dropping away to leeward and repeating the manœuvre as often as was possible. Perhaps La Gallissonnière was the man who devised the method, or perhaps it may have originated by accident during his action with Byng off Minorca and been subsequently developed after study by the leaders of naval thought. The whole principle of keeping the fleet out of harm’s way, strategically if possible and tactically if necessary, was sufficient, for most of the period of the war just beginning, to disconcert the English command, although it is strongly to be suspected that the English did not realize until the closing period of the war that they were struggling against a particular system; especially when the entry of Spain and of the United Provinces into the war gave the allies a superiority of numbers which made, on occasions, the English Admirals just as chary of offering battle as their opponents were of accepting it. Yet when the situation began to dawn upon the English they began steadily to devise means to turn it to their advantage. Previously the long line ahead had brought good results when opposed to another line ahead which was equally willing to fight a battle; but it was a helpless formation, except under particular circumstances, when an attempt was to be made to compel battle. Something else had to be done; and, once the English had grasped that, pamphlets and private correspondence began to circulate in the endeavour to find a remedy.